Abstract

The mechanisms by which a primary tumor affects a selected distant organ before tumor cell arrival remain to be elucidated. This report shows that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are significantly increased in lungs of mice bearing mammary adenocarcinomas before tumor cell arrival. In the premetastatic lungs, these immature myeloid cells significantly decrease IFN-γ production and increase proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, they produce large quantities of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and promote vascular remodeling. Deletion of MMP9 normalizes aberrant vasculature in the premetastatic lung and diminishes lung metastasis. The production and activity of MMP9 is selectively restricted to lungs and organs with a large number of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Our work reveals a novel protumor mechanism for Gr-1+CD11b+ cells that changes the premetastatic lung into an inflammatory and proliferative environment, diminishes immune protection, and promotes metastasis through aberrant vasculature formation. Thus, inhibition of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells could normalize the premetastatic lung environment, improve host immunosurveillance, and inhibit tumor metastasis.

Introduction

Tumor metastasis is the primary cause of death for most cancer patients. There are few effective treatment options (1). In the metastasis process, tumor cells must disseminate, intravasate into blood vessels at the primary tumor site, travel through the vascular systems, arrest in capillary beds, and subsequently extravasate into the organ parenchyma. In the hostile distant organ, they must escape from host immune surveillance to survive and grow. Interestingly, many tumors show a metastatic predisposition to selected organs. This is believed to be influenced by inherent molecular differences in tumor cells (2–5) and their interaction with host factors (6). In recent years, genes that are responsible for the acquisition of metastatic abilities, metastatic tissue tropism, and the nature of metastasis predisposition factors have been identified (7). At the same time, cancer-associated host immune reaction and inflammation are indispensable factors in tumor progression and metastasis (8–12).

Emerging data suggest that host bone marrow–derived hematopoietic progenitor cells and myeloid cells form a “premetastatic niche” regulating organ-specific tumor spread (13–18). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 1 (VEGFR1)–positive cells were shown to home to distant sites forming premetastatic cell cluster before tumor cell arrival. Neutralization of VEGFR1 function or depletion of VEGFR1+ cells from the bone marrow abrogates the formation of these premetastatic clusters and prevents tumor metastasis (14). Distant primary tumors of lung cancer and melanoma induce the inflammatory chemoattractants S100A8 and S100A9 in the premetastatic lung. S100A8 and S100A9 attract macrophages and tumor cells. Neutralizing S100A8 and anti-S100A9 antibodies block the migration of tumor cells and macrophages (15). Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling in primary tumors induces angiopoietin-like 4 expression, which disrupts vascular endothelial cell-cell junctions and increases the permeability of lung capillaries, thus facilitating the trans-endothelial passage of tumor cells. This effect is specific for tumor metastasis to the lungs but not bone or brain (19). A recent report suggests a critical role for lysyl oxidase in premetastatic niche formation (17). Together, these data have created a renewed interest in the “seed and soil” theory. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms that promote the metastasis of a primary tumor to a selected distant location remain to be elucidated.

Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells are significantly overproduced in the bone marrow and spleens of tumor-bearing mice as well as in the peripheral blood of cancer patients (20, 21). This is partially regulated by granulocyte colony stimulating factor and Bv8 or prokineticin 2 (22). Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells are composed of immature myeloid cells at the early stages of differentiation (21, 23). They are also known as myeloid-derived suppressor cells. They represent one mechanism of how tumors escape from immune system control and compromise the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy (20, 24, 25). In addition, these cells infiltrate into tumors, and promote tumor angiogenesis and metastasis (23, 26). Consistent with the proangiogenic function, they also mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment (27). In this study, we report that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells infiltrate into the lungs of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice before tumor cell arrival. They promote tumor metastasis and subsequent growth through the creation of an appropriate environment that is proliferative, immune suppressive, and inflammatory. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells also produce a large quantity of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and regulate blood vessel remodeling, which leads to increased tumor cell extravasation. Our results suggest that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells alter the overall landscape of the premetastatic lung environment and tip the balance of immune protection to tumor promotion.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and mice

4T1 and 4T1-GFP cell lines were maintained per standard cell culture techniques. Human umbilical vascular endothelial cell (HUVEC) line was cultured in LONZA endothelial growth media. Eight- to 10-week-old female BALB/c mice were from Harlan, Inc. MMP9 knockout (ko) mice were obtained from Dr. Zena Werb at the University of California, San Francisco. The studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Flow cytometry analysis and single-cell sorting

Single-cell suspensions were made from spleens, bone marrow (BM), lungs, or tumor tissues (28). The cells were labeled with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies (BD Pharmingen) and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For the flow cytometry analysis of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from various organs, the vascular perfusion was performed before sacrificing the mice. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells were sorted with a FACStarPlus flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Green fluorescent protein PCR

Peripheral blood was collected by heart puncture in mice bearing 4T1-GFP tumors. DNA was extracted from nucleated cells. The presence of green fluorescent protein (GFP) was examined by GFP-PCR.

IFN-γ ELISPOT

Single-cell suspension from normal lungs and lungs of mice bearing 4T1 tumors at day 14 were prepared; 2 × 105 cells were in each well of IFN-γ ELISPOT plate, procedure per manufacture recommendations (BD). The ELISPOT plate was scanned in ImmunoSpot (Cellular Technology Ltd.), and quantification was assessed using the CTL Scanning and CTL counting 4.0.

Cytokine antibody array

Tissues and cells were homogenized, lysed, and processed per the manufacturer’s protocol (Raybiotech). The relative quantification was measured by dot density using the Photoshop software following the formula below:

MMP9 zymography

Tissues and cells were homogenized and lysed as described (23). Aliquots of 20 μg of proteins were analyzed by gelatin zymography on SDS-PAGE with substrate (1 mg/mL of gelatin).

Tumor growth and whole-lung mounting

4T1 tumor cells (5 × 105 cells) were s.c. injected into the right flank of BALB/c mice for ~35 days. The size of tumors was determined (23). Tumor nodules in the lung were counted and photographed (26).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were incubated with antibodies for Gr-1 (BD), VWF8 (Dakocytomation), and GFP (Clontech), following procedures from the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). For immunofluorescence (IF), Gr-1, MMP9 (Abcam), VE-cadherin (Abcam), αSMA (DAKO), VWF8, and Alexa flour 488 goat anti-rat and 594 goat anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes) antibodies were used. The slides were mounted with Prolong Gold + 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen) and examined using fluorescence microscopy. Quantification was assessed using MetaMorph version 7.5.3.0.

Lung perfusion and confocal microscopy

Dextran-rhodamine (2 million Dalton, 100 μL, 5 mg/mL) was administered by retro-orbital injection. Mice were anesthetized, and a small incision was made to expose the trachea, through which mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde at the speed of 6 mL/min for 5 minutes. The trachea, pulmonary artery and veins, the aorta, and inferior vena cava were clamped by hemostats and then ligased using surgical gut to prevent dextran leakage. The lungs were examined under Zeiss Inverted LSM510 Confocal Microscope.

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy was carried out in the Vanderbilt Research Electron Microscopy Core following the standard procedures. Thin sections were viewed with an FEI CM12 transmission electron microscope after staining with lead citrate and uranyl acetate.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the Student’s t test and were expressed as mean± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant when the P value was <0.05.

Results

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are recruited to the lungs of mammary tumor hosts before tumor cell arrival

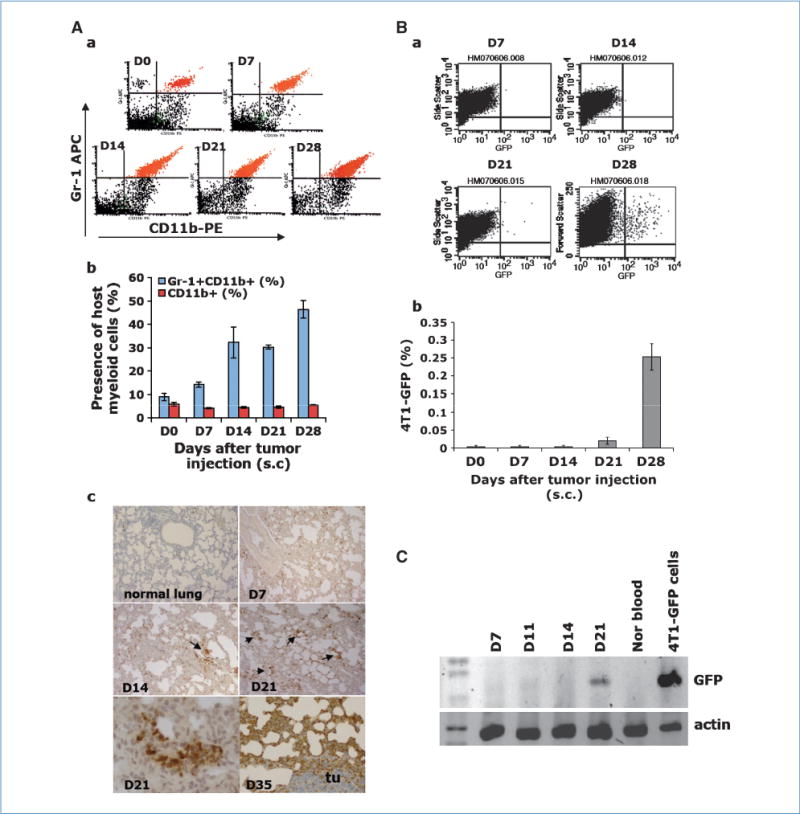

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are overproduced in tumor hosts. They exert systemic immune suppression and modulate the tumor microenvironment. We asked whether Gr-1+CD11b+ cells affect the distant organ environment and contribute to premetastatic niche formation. We used the 4T1 breast tumor model, which shares many characteristics with human breast cancer, particularly its ability to spontaneously metastasize to lungs. Using flow cytometry analysis, we first examined the presence of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the lungs of mice bearing 4T1-GFP tumors at different times after s.c. tumor inoculation. There was a clear increase of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the lung of these tumor-bearing mice when compared with normal mice (Fig. 1Aa and b). Interestingly, Gr-1-CD11b+ cell numbers were not increased (Fig. 1Ab), indicating the increase in Gr-1+CD11b+ cells is cell type specific. Because Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the lungs of tumor-bearing mice expressed both Gr-1 and CD11b (Fig. 1Aa), this allowed us to use immunohistochemistry (IHC) of anti–Gr-1 antibody to visualize Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells form clusters in the lungs at day 14, increasing significantly in number by day 21 (D21, arrows), with massive numbers on day 35 (Fig. 1Ac). The results are consistent with flow cytometry analysis.

Figure 1.

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells infiltrate into the lungs of mice bearing 4T1 tumors prior to tumor cell arrival. D0, non–tumor-bearing mice; D7, D14, D21, and D35, days after 4T1 tumor inoculation (s.c.). Aa, flow cytometry of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in total lung single-cell suspension. Ab, quantitative data for Aa. Ac, IHC of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in lung sections. Bottom left, enlarged Gr-1+CD11b+ cell cluster. Tu, a tumor metastasis nodule. Ba, flow cytometry of 4T1-GFP tumor cells in lungs. Bb, quantitative data for Ba. C, GFP-PCR in nucleated peripheral blood cells from mice bearing 4T1 tumors. Shown is one of the two experiments performed. Three to four mice per group were examined for all experiments.

We next examined the time course of metastatic 4T1 cell arrival in lungs of mice bearing 4T1-GFP tumors using flow cytometry analysis. We did not detect any 4T1-GFP tumor cells until 14 days after tumor inoculation (Fig. 1Ba and b). Further, we performed GFP-PCR for nucleated cells isolated from peripheral blood of mice bearing 4T1-GFP tumors. We did not detect GFP in over 90% of mice examined until D21 after tumor inoculation (Fig. 1C). This is further confirmed by GFP-PCR of lung samples from these mice (data not shown). These results suggest that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells were present in the lungs before metastatic tumor cell arrival. In addition, GFP staining of serial lung sections from day 14 lung (lungs of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice 14 d after tumor inoculation) did not detect any GFP-positive tumor nodules or positive cells. We thus identified the time between tumor inoculation to day 14 as premetastatic phase, and day 28 or after as later stage of tumor growth. This agrees with a previously published report in which the authors found tumor cells arrived in the lung 16 to 18 days after tumor inoculation (14). We further found that 81.2% of the cells are Ly6G+Ly6C low; 5% are Ly6G-Ly6C high; and 1.6%, 2.5%, 3.7%, and 6.7% express F4/80+, MMR+, CX3CR1+, and CCR2+, respectively. These data indicate that these Gr1+CD11b+ cells are granulocytic and are not macrophages (Supplementary Fig. S1). The presence of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in premetastatic lungs was also shown in the PyVmT/Tgfbr2MGKO genetic mouse mammary tumor model (Supplementary Fig. S2).

We further examined the presence of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in various organs in the premetastatic phase and during the later stage of tumor growth. We found that although there was a significantly increased Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the lungs of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice during the premetastatic phase, this was not the case for liver, pancreas, kidney, brain, ovary, or uterus (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, 28 days after tumor injection, Gr-1+CD11b+ cells were only found in the organs that harbor tumor metastasis including lung, liver, and spleen (Supplementary Fig. S2), but not in those in which tumor metastasis did not occur including kidney, uterus, ovary, brain, and pancreas (Supplementary Fig. S2). This is consistent with the tropisms of 4T1 cells that primarily metastasize to the lung. However, small percentages of tumor cells also go to liver and spleen.

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells inhibit IFN-γ production in premetastatic lung

We stained serial lung sections with anti–Gr-1 antibody for Gr-1+CD11b+ cells and anti-GFP antibody for 4T1-GFP tumor cells. We did not observe colocalization of Gr-1+CD11b+ cell cluster with tumor cells in premetastatic lung (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Gr-1+CD11b+ cells did not contribute to vasculogenesis (Supplementary Fig. S3B), different from what we observed in the primary tumor microenvironment (23). Instead, we noticed a formation of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissues are mucosal lymphoid organs often observed in peribronchial, perivascular, and interstitial areas throughout the lungs of mice with pulmonary infection (29, 30).

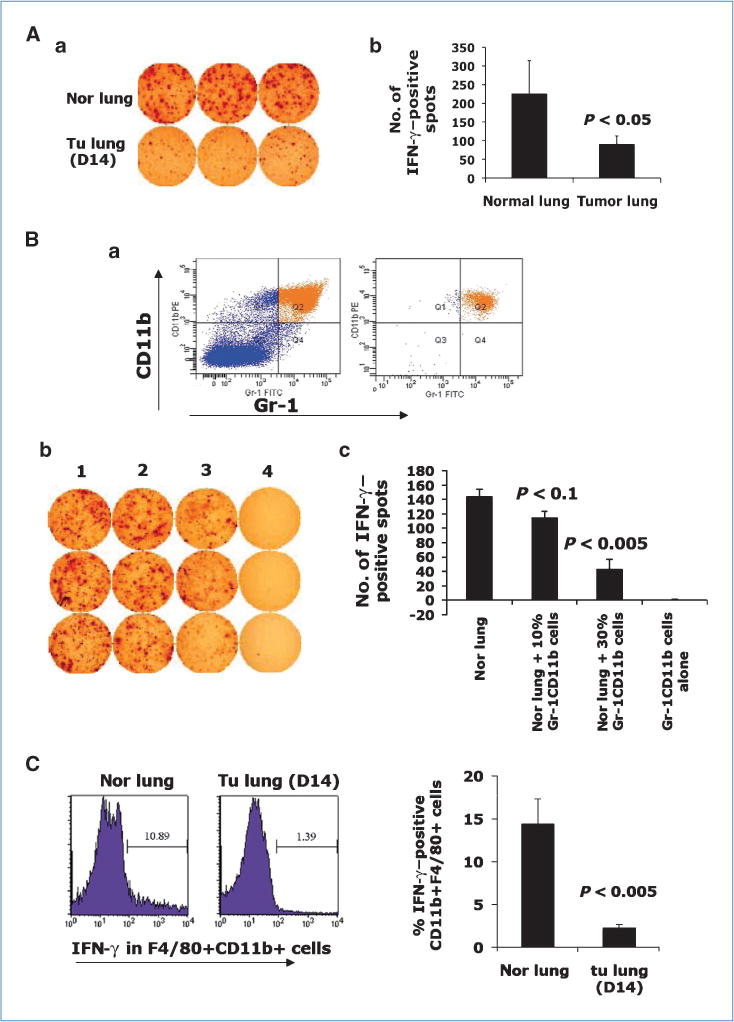

IFN-γ is one of the key cytokines in the host immune defense against tumor. We next examined IFN-γ production in the premetastatic lung using IFN-γ ELISPOT. There was a significantly decreased number of IFN-γ–positive spots from day 14 lung when compared with the normal lung (Fig. 2Aa). We next sorted Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from the lungs of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; Fig. 2Ba) and cocultured them in various numbers (2 × 105, 1 × 106) with 2 × 106 single cells from normal lung (referred to as normal lung cells hereafter). Very interestingly, the coculture produced a significantly decreased number of IFN-γ–positive spots (Fig. 2Bb, column 2 and 3) than normal lung cells alone (P < 0.005; Fig. 2Bb column 1 and Bc). As expected, Gr-1+CD11b+ cells alone did not produce any IFN-γ–positive spots. Further examination using flow cytometry analysis showed that the IFN-γ–producing cells are mostly macrophages, and they are significantly decreased in the day 14 premetastatic lung compared with normal lung (Fig. 2C). In addition, no difference in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell subsets between normal lung and day 14 tumor lung was found (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Our data suggest that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells significantly decreased immune protection in the premetastatic lung.

Figure 2.

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells inhibit IFN-γ production in premetastatic lung. Aa, IFN-γ ELISPOT from normal lungs and day 14 lungs. Ab, quantitative data from Aa. Ba, Gr-1+CD11b+ cells before (left) and after (right) sorting. Bb, IFN-γ ELISPOT of normal lung single-cell suspension cocultured with sorted Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Column 1, normal lung alone (2 × 106); columns 2 to 3, coculture of normal lung (2 × 106) with Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (2 × 105 for column 2, 1 × 106 for column 3); column 4, Gr-1+CD11b+ cells alone (2 × 106). Bc, quantitative results for Bb. Samples are in triplicate. One experiment of two is shown. C, flow cytometry analysis of IFN-γ expression in F4/80 +CD11b+ cells in lungs of normal and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. Three to four mice were analyzed; right, the quantitative data.

A proliferative, immune-suppressive, and inflammatory premetastatic lung environment

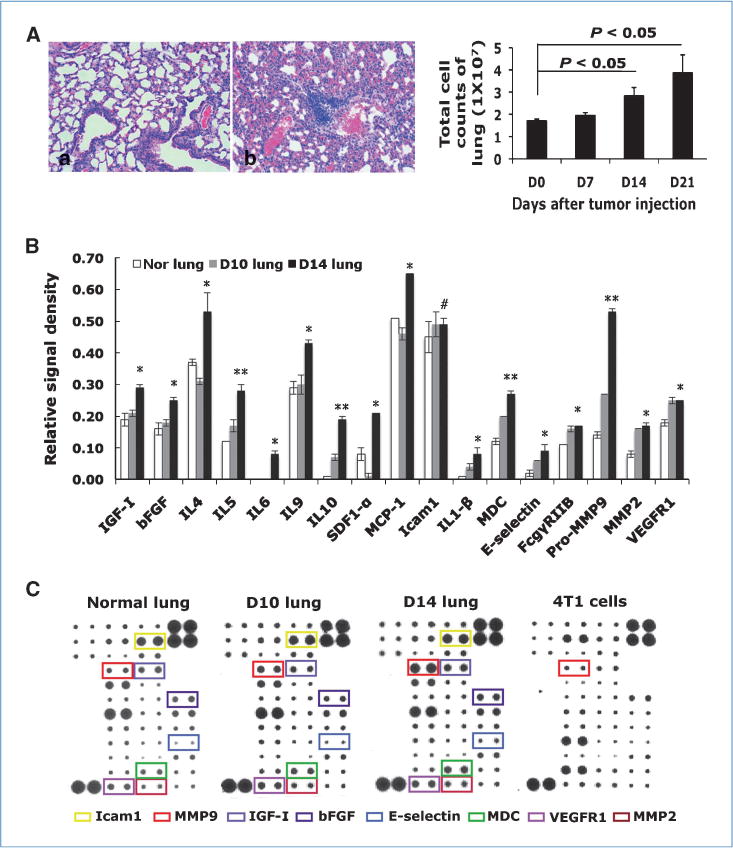

We observed a dramatic increase of cellular density and decreased air space in day 14 lung (Fig. 3Ab) compared with normal lung (Fig. 3Aa) by H&E staining, which was further confirmed by total cell counts (Fig. 3A, right). This increase was correlated with the increase of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells as shown in Fig. 1A. To investigate the possible environmental change in the premetastatic lung and underlying mechanisms, we extracted protein from normal lungs, day 10, and day 14 lung, and performed a cytokine and chemokine antibody array analysis. The relative signaling intensity was quantified by measuring dot density. Very interestingly, there was a clear change of cytokine/chemokine and protease profiles in the premetastatic lung compared with normal lung (Fig. 3B and C). Notably, we observed a significant elevation of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and insulin growth factor I (IGFI), suggesting a highly proliferative phenotype. In addition, Th2 cytokines interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-10 were clearly elevated (Fig. 3B and C). As these Th2 cytokines are well known for their suppressive effect on immune surveillance, these data are consistent with our observation of the immune suppression properties of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the premetastatic lung in reducing IFN-γ production. Further, proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, SDF-1, and macrophage-derived chemokine were significantly upregulated (Fig. 3B and C). The expression of MMP9 and MMP2 is also significantly elevated, especially MMP9 (P < 0.01), when compared with normal lung (Fig. 3B and C). No changes in Icam-1 (Fig. 3B and C), lymphotactin, resistin, and VEGFR2, were observed (data not shown). This phenotype was recapitulated by ex vivo coculture of a lung single-cell suspension (1 × 106 cells) with sorted Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (2.5 × 105), with a significant elevation in the production of IGFI, bFGF, IL-5, SDF-1, macrophage-derived chemokine, and MMP9 as well as VEGFR1 (Supplementary Fig. S5A). These data suggest a general proliferative, immune-suppressive, and inflammatory environment in the premetastatic lung that is likely mediated by Gr-1+CD11b+ cells.

Figure 3.

Cytokine/chemokine profiling of premetastatic lung and normal lung. A, increased tissue density in premetastatic lung by H&E staining (Aa, normal lung; Ab, day 14 lung) and total cell counts from lungs at different days after tumor injection (right). Three to four mice per group. B, relative signal intensity from cytokine/chemokine array. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; #, P > 0.05. C, cytokine/chemokine array. Cytokine of interest is labeled with a specific color. Shown is one of the two experiments performed.

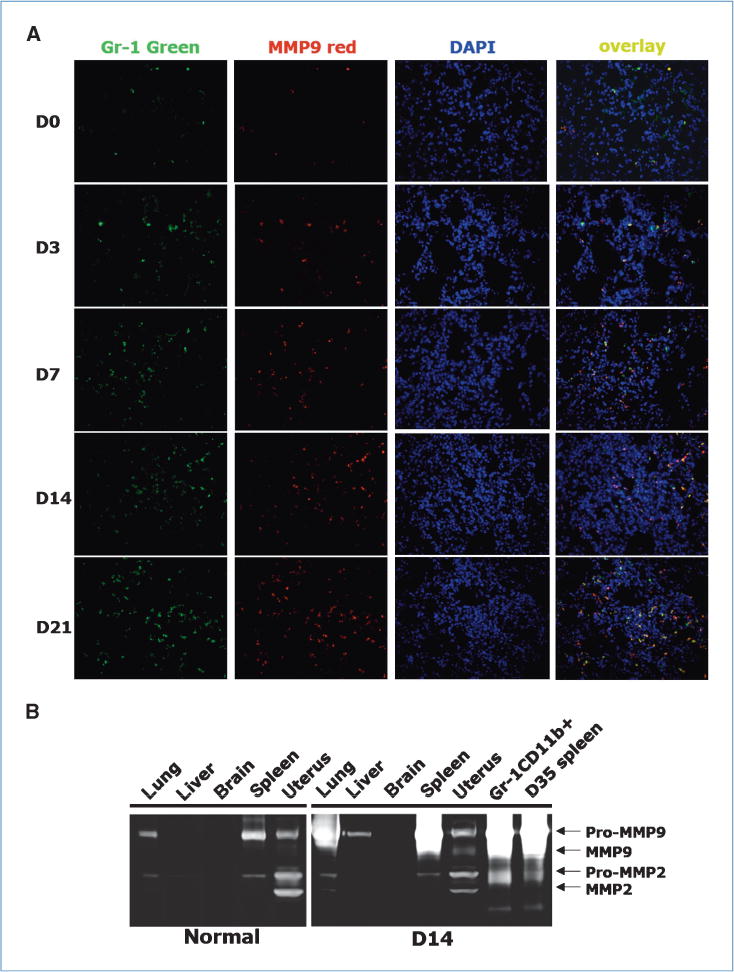

MMP9 was highly expressed and activated in the premetastatic lung; Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are the major contributors

Of all factors upregulated in the premetastatic lung, MMP9 is one of the most significant, in day 10 lung and to a much greater extent in day 14 lung (Supplementary Fig. S5A; Fig. 3B and C). Surprisingly, the 4T1 tumor cells only produced a basal level of MMP9, similar to normal lung (Fig. 3B). The expression of MMP2 was also increased but to a lesser extent (Fig. 3B and C). MMP3 was not increased (data not shown), indicating the increase in MMP9 and MMP2 in the premetastatic lung is a specific effect.

We performed co-IF staining of MMP9 and Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in lung sections at various time after tumor inoculation. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells clearly overlapped with MMP9-positive cells (Fig. 4A), and they were quantitatively correlated in a time response manner (Supplementary Fig. S5B). We next used gelatin zymography to examine various organs harvested 14 days after 4T1 tumor injection. We found significantly increased MMP9 activity in the day 14 lung compared with that of normal mice (Fig. 4B). MMP9 activity did not increase in liver, brain, or uterus (Fig. 4B). Further, sorted Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from premetastatic lung showed high MMP9 activity (Fig. 4B). Not surprisingly, there was also a high level of MMP9 production/activity in the spleen from mice bearing day 14 or day 35 tumors as a large number of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are produced in the spleen. Together, our data show a significant increase in MMP9 activity in the premetastatic lung, and that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are likely the major cause of this increase.

Figure 4.

Significantly elevated MMP9 in premetastatic lung with Gr-1+CD11b+ cells as the major resource. A, co-IF staining of Gr-1 (green) and MMP9 (red) in lungs at different day after tumor injection. Blue, nuclei. One experiment from three is shown. B, gelatin zymography of protein lysis from indicated organs of normal mice and mice bearing 14 day 4T1 tumors. One of three experiments is shown.

Aberrant and leaky vasculature in the premetastatic lung

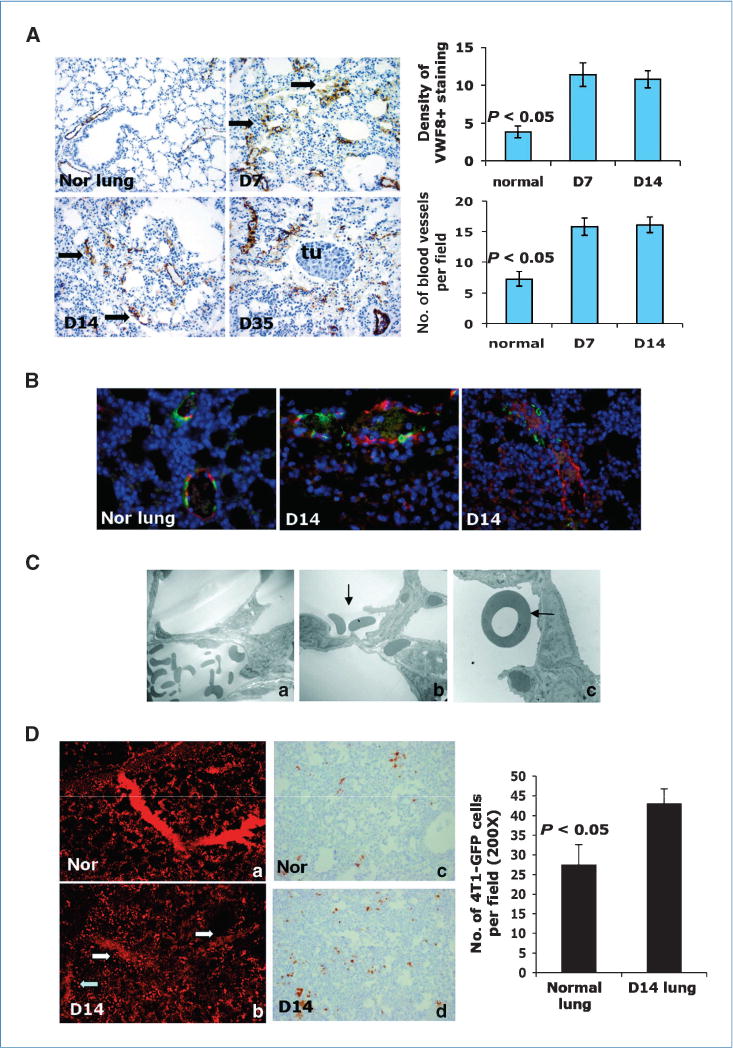

Vasculature is a pivotal mediator of metastasis. To examine whether there is a difference in vasculature between the normal lung and the premetastatic lung, we stained lung sections with Von Willebrand factor 8 (VWF8), a marker for endothelial cells. We observed significantly more VWF8-positive cells and capillary vascular structure with apparent disorganized morphology from premetastatic lungs than normal lung (Fig. 5A). We next costained the lung sections with anti-VWF8 and αSMA antibodies to examine vasculature maturity. The VWF8-positive vessels in day 14 lungs lacked the double staining for αSMA (Fig. 5B), indicating poor pericyte coverage on the vasculature. Electron microscopy revealed RBC in the alveoli of the premetastatic lung (Fig. 5Cb and c, arrow), which is totally absent in normal lung (Fig. 5Ca). There was also a degraded matrix and collagen in basal membrane of blood vessel in the premetastatic lung compared with that from normal lung (Supplementary Fig. S6A). These data indicate a leaky vasculature in the premetastatic lung, which was confirmed by retro-orbital injection of dextran-rhodamine. Confocal imaging of the vascular structure ex vivo showed disorganized vascular networks in the premetastatic lungs (Fig. 5Db) compared with normal lung (Fig. 5Da). Interestingly, there was a notable decrease in fluorescence intensity within the vessels accompanied by increased fluorescence intensity in the perivascular sites (Fig. 5Db). We next injected 4T1-GFP cells through the tail vein in mice bearing day 14 tumor. The lungs were perfused with PBS 24 hours later. The lung sections were then examined with GFP IHC for the presence of 4T1-GFP cells. Significantly more 4T1-GFP cells were found in the lungs of mice bearing day 14 tumor than that of normal mice (Fig. 5Dc and d). Metastatic tumor nodules were found around the leaky blood vessel in late-stage tumors (Supplementary Fig. S6B). Together, these data show aberrant and leaky vasculature in the premetastatic lung that likely promote tumor cells to breach lung capillaries.

Figure 5.

Aberrant and leaky vasculature in premetastatic lung. A, VWF8 staining. Days after s.c. tumor inoculation are indicated. Arrows, vessel-like structure. Tu, metastasis nodules. Quantitative data were obtained in a blinded fashion (top right and bottom). B, co-IF staining of VWF8 (red) and αSMA (green). C, electron microscopy of blood vessel in normal lung (Ca) and day 14 lung (Cb–c). Arrows, RBC in alveoli. Two to three mice were examined. D, vascular leakage in premetastatic lung; Da and b, confocal imaging. Four to five mice were examined. Dc and d, IHC of GFP to detect 4T1-GFP tumor cells in the lungs. Three to four mice were examined. GFP-positive cells were counted in a blinded fashion (right).

Host-derived MMP9 regulates premetastatic abnormal vasculature formation; deletion of MMP9 significantly decreases lung metastasis

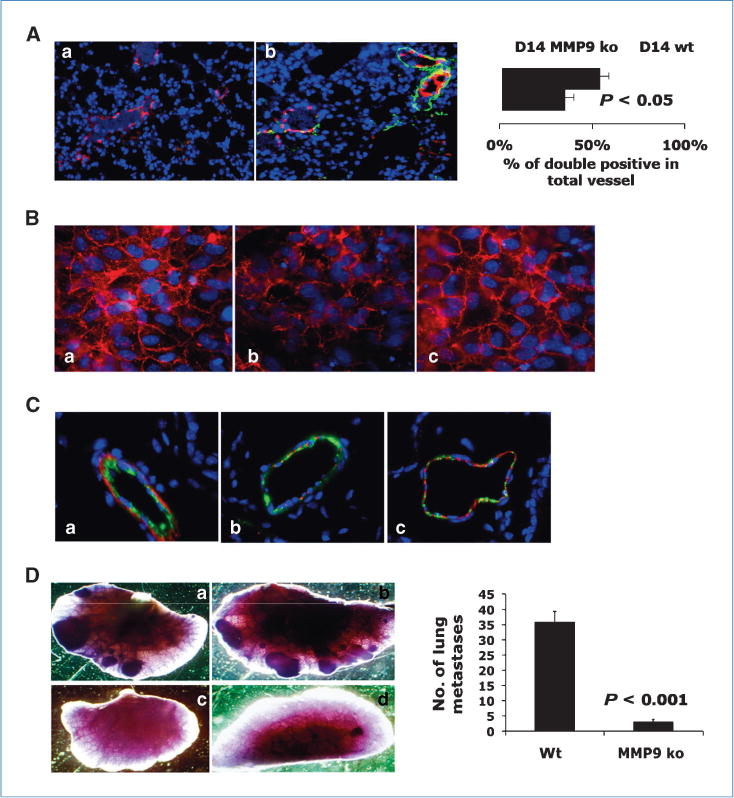

MMP9 is a critical regulator of tumor vascular remodeling (31). We asked whether host-derived MMP9 contributed to aberrant vasculature formation in the premetastatic lung. Lung sections from MMP9 ko and wild-type (wt) mice bearing 4T1 tumor were stained for VWF8 or αSMA. We observed significantly more blood vessels with double staining of VWF8 and αSMA in the MMP9 ko premetastatic lung (Fig. 6Ab) than the wt lung (Fig. 6Aa, right). As VE-cadherin junctions are important for the integrity of vascular endothelium, we next tested whether Gr-1+CD11b+ cells affect VE-cadherin junctions in vitro. We cocultured wt or MMP9 ko Gr-1+CD11b+ cells with confluent HUVEC. HUVEC cocultured with wt Gr-1+CD11b+ cells showed disrupted and diffused VE-cadherin expression (Fig. 6Bb), whereas HUVECs alone were sharp and localized in cell-cell junctions (Fig. 6Ba). Interestingly, HUVEC cocultured with MMP9 ko Gr-1+CD11b+ cells was very similar to that of HUVEC cultured alone (Fig. 6Bc). In vivo examination showed disrupted VE-cadherin junctions (Fig. 6Cb) in day 14 lung when compared with normal lung. Deletion of MMP9 decreased such disruption (Fig. 6Cc). These data suggest that MMP9 provided by Gr-1+CD11b+ cells promotes decreased pericyte coverage and disruption of VE-cadherin junctions in vascular endothelium. These data agree with significantly diminished tumor metastasis nodule formation with MMP9 deletion in the host (Fig. 6D), with no significant difference in primary tumor growth between wt and MMP9 ko (Supplementary Fig. S7). Together, these data support that the premetastatic lung permits increased extravasation of tumor cells and metastasis nodule formation in vivo. MMP9 produced by Gr-1+CD11b+ cells is a critical mediator in this process.

Figure 6.

Deletion of MMP9 in host decreased aberrant vascular phenotype and diminished lung metastasis. A, co-IF staining of VWF8 (red) and αSMA (green) in lungs of wt or MMP9 ko bearing 4T1 tumors day 14 after injection. Right, quantitative data. Three to four mice examined. B, VE-cadherin staining (red) of HUVEC cocultured with wt (b) or MMP9 ko Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (c), or HUVEC alone (a). One of two experiments is shown. C, co-IF staining of VWF8 (green) and VE-cadherin (red) in lungs of nontumor-bearing (a), wt (b), and MMP9 ko mice (c) bearing 4T1 tumors day 14 after injection. D, whole-lung mounts of wt (a and b) and MMP9 ko (c and d) mice bearing 4T1 tumors 35 d after s.c. injection. Right, number of lung metastatic nodules (P < 0.001). Five to six mice per group.

Discussion

When immune cells infiltrate into a specific organ, a complex set of interactions occurs. This is particularly true in a tumor-bearing host, which results in either tumor destruction by immunosurveillance or tumor outgrowth. Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells exert protumor activities through the reduction of IFN-γ, elevation of inflammatory cytokines, activation of MMP9, and vascular remodeling in the premetastatic lung.

The premetastatic phase was defined as up to 14 days following implantation using several technologies including flow cytometry, IHC, and GFP-PCR of lung tissues and nucleated peripheral blood cells (Fig. 1), which is similar to the 16- to 18-day time frame published (14). Gr-1+CD11b+ cells did not form a premetastatic niche in lungs in the 4T1 and PyVmT/Tgfbr2MGKO mouse models (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S3). This is in contrast to what was previously reported (14, 17), but agrees with a recent report in which inhibition of premetastatic niche formation with the blockade of VEGFR1 activity did not affect the rate of spontaneous metastasis formation (32). Rather, we observed increased tissue cellular density, decreased air space, and profound molecular changes in the premetastatic lung characterized by significantly decreased IFN-γ production (Fig. 2), elevated growth factors and TH2 cytokines, as well as elevated proinflammatory factors (Fig. 3B and C) and the matrix-degrading enzyme MMP9 (Figs. 3B and C, and 4) that regulates aberrant vasculature formation. Our data support a general microenvironmental change with the infiltration of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the premetastatic lung, which is more permissive for immune evasion, extravasation, survival, and proliferation of metastatic tumor cells.

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells significantly decreased IFN-γ production in the premetastatic lung (Fig. 2). There was also significantly elevated Th2 cytokine production (Fig. 3B and C). CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells did not seem to be involved (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Our observations are supported by a recent report about the tumor microenvironment in which immune cells may dictate a shift from inflammation/immune responses to anti-inflammatory/immune-suppressive responses (Th1/Th2-like cytokine shift) within the metastatic liver milieu (33). Our results are also in agreement with recent data showing that CD25Hi T regulatory cells were not involved in breast tumor metastasis (34). Our data disagree with a recent report showing breast lung tumor metastasis requires CCR4+ regulatory T cells (35). Our results are also different from that of a draining lymph node study in which immature dendritic cells were found to produce TGFβ that stimulated CD4CD25FoxP3 regulatory T-cell proliferation (36). Nevertheless, our data suggest that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in premetastatic lung decreased IFN-γ and elevated Th2 cytokine production, thus diminishing host immune surveillance.

We observed a clear difference in vasculature between the normal and the premetastatic lung. The vessels in the premetastatic lung are increased in number, dilated, tortuous, and leaky. We reached our conclusion using multiple experimental approaches. Poor coverage of pericytes and disrupted VE-cadherin likely contribute to decreased vascular integrity and maintenance. Pericytes are quite abundant on small venules and arterioles but sparse or disorganized in tumor blood vessels. When lost, the vessels become leaky, hemorrhagic, and hyperdilated (37). The significant vascular remodeling in the premetastatic lung we observed is consistent with the observations in mice bearing Lewis Lung Carcinomas (14) and B16/F10 melanoma (38), although MMP9 was not reported as an important mediator (38). MMP9 is an important mediator of angiogenesis and vasculature remodeling in the tumor microenvironment (31, 39–42) through increasing VEGF bioavailability (43, 44) or activation of TGFβ. However, we did not find any significant change in VEGF or TGFβ production between the normal lung and the premetastatic lung (data not shown). Recent studies report a dichotomous role for VEGF and VEGFR2 signaling as both a promoter of endothelial cell function and a negative regulator of vascular smooth muscle cells in vessel maturation (45). VEGF can also act as an inhibitor of neovascularization and has the capacity to disrupt vascular smooth muscle cell function due to VEGF-mediated activation of VEGFR2 suppressing platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFβ) signaling (46). Our research specifically focuses on the premetastatic distant lung in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice and shows that MMP9 from infiltrating Gr-1+CD11b+ cells regulates vascular remodeling before tumor cell arrival.

The specific metastatic location of a certain tumor type is governed by many factors including blood flow patterns, tumor stage, and tumor cell interactions with the vascular endothelium (47, 48). We observed highly elevated production and activity of MMP9 that was restricted to lungs and organs due to abundant Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. This is in contrast to normal lung or in other organs of the same tumor-bearing mice in the premetastatic phase, including liver, brain, uterus, and kidney (Supplementary Fig. S2; Fig. 4B), suggesting a certain level of organ selectivity. Recent studies suggest that bone marrow–derived cells are recruited to premetastatic sites. Several pathways have been implicated. Resident fibroblast-like stromal cells express fibronectin under primary tumor influence, and interact and recruit VLA-4+VEGFR1+ myeloid progenitor cells (14). In addition, inflammatory chemoattractants S100A8 and S100A9 are induced in lung and attract CD11b+ macrophages for premetastatic niche formation, which is mediated by VEGF-A, tumor necrosis factor α, and TGFβ (15). Very recently, one study reported that hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase accumulates at premetastatic sites, cross-links collagen in the basement membrane, and recruits CD11b+ myeloid cells to form the premetastatic niche (17). In our studies, we devoted significant effort to identify possible mechanisms responsible for Gr-1+CD11b+ cell recruitment to the premetastatic lung. Our preliminary data suggest that TGFβ might be involved, as treatment with TGF-β–neutralizing antibody decreased the number of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in premetastatic lung,5 which is currently under investigation.

Collective genetic inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor ligand epiregulin, COX-2, MMP1, and MMP2 in human breast cancer cells abrogate the extravasation from lung capillaries (49). TSU68, an inhibitor of VEGFR2, PDGFRβ, and FGFR1, modulates the microenvironment in the liver before the formation of colon cancer metastasis (50). Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are found in large quantities in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of how Gr-1+CD11b+ cells affect the pre-metastatic lung will allow us to identify novel molecules for cancer detection and targeting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lalage Wakefield for the critical reading of the manuscript; Dr. Zena Werb for sharing the MMP9 ko mice; Dr. Charles Lin and Laura Debusk for the advice in HUVEC culture and vasculature studies; David Bader for editorial assistance; Vanderbilt VA FACS Core, and the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center Cell Imaging Core, and Research Electron Microscopy Core for the technical assistance; Barbara Taylor for the technical support in FACS core; and Susan Garfield for the technical support in the confocal microscopy core of NCI.

Grant Support

Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, Center for Cancer Research (L. Yang); and grants CA085492, CA102162, and U54 CA126505 (H. Moses). The Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center cores are supported by grant number CA068485.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes RO. Metastatic potential: generic predisposition of the primary tumor or rare, metastatic variants-or both? Cell. 2003;113:821–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:537–49. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell. 2006;127:679–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:453–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen DX, Massague J. Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:341–52. doi: 10.1038/nrg2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bui JD, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunosurveillance, immunoediting and inflammation: independent or interdependent processes? Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeNardo DG, Coussens LM. Inflammation and breast cancer. Balancing immune response: crosstalk between adaptive and innate immune cells during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:212. doi: 10.1186/bcr1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Immune surveillance: a balance between protumor and antitumor immunity. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allavena P, Garlanda C, Borrello MG, Sica A, Mantovani A. Pathways connecting inflammation and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiratsuka S, Nakamura K, Iwai S, et al. MMP9 induction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 is involved in lung-specific metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:289–300. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1369–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan RN, Rafii S, Lyden D. Preparing the “soil”: the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11089–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, et al. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the pre-metastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–31. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padua D, Zhang XH, Wang Q, et al. TGFβ primes breast tumors for lung metastasis seeding through angiopoietin-like 4. Cell. 2008;133:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, et al. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: a mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166:678–89. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shojaei F, Wu X, Zhong C, et al. Bv8 regulates myeloid-cell-dependent tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;450:825–31. doi: 10.1038/nature06348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L, Debusk LM, Fukuda K, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serafini P, De Santo C, Marigo I, et al. Derangement of immune responses by myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:64–72. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang L, Huang J, Ren X, et al. Abrogation of TGFβ signaling in mammary carcinomas recruits Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells that promote metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shojaei F, Wu X, Malik AK, et al. Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b(+)Gr1(+) myeloid cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:911–20. doi: 10.1038/nbt1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ljung BM, Mayall B, Lottich C, et al. Cell dissociation techniques in human breast cancer-variations in tumor cell viability and DNA ploidy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1989;13:153–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01806527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moyron-Quiroz JE, Rangel-Moreno J, Kusser K, et al. Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat Med. 2004;10:927–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rangel-Moreno J, Hartson L, Navarro C, Gaxiola M, Selman M, Randall TD. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3183–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI28756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–44. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson MR, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. VEGFR1-activity-independent metastasis formation. Nature. 2009;461:E4. doi: 10.1038/nature08254. discussion E5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, et al. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, et al. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olkhanud PB, Baatar D, Bodogai M, et al. Breast cancer lung metastasis requires expression of chemokine receptor CCR4 and regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5996–6004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S, et al. Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-β-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:919–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergers G, Song S. The role of pericytes in blood-vessel formation and maintenance. Neurooncol. 2005;7:452–64. doi: 10.1215/S1152851705000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y, Song N, Ding Y, et al. Pulmonary vascular destabilization in the premetastatic phase facilitates lung metastasis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7529–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coussens LM, Tinkle CL, Hanahan D, Werb Z. MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 2000;103:481–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, et al. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell. 2002;109:625–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00754-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heissig B, Rafii S, Akiyama H, et al. Low-dose irradiation promotes tissue revascularization through VEGF release from mast cells and MMP-9-mediated progenitor cell mobilization. J Exp Med. 2005;202:739–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, et al. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du R, Lu KV, Petritsch C, et al. HIF1α induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:206–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee CG, Link H, Baluk P, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces remodeling and enhances TH2-mediated sensitization and inflammation in the lung. Nat Med. 2004;10:1095–103. doi: 10.1038/nm1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stockmann C, Doedens A, Weidemann A, et al. Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor in myeloid cells accelerates tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;456:814–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenberg JI, Shields DJ, Barillas SG, et al. A role for VEGF as a negative regulator of pericyte function and vessel maturation. Nature. 2008;456:809–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:563–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown DM, Ruoslahti E. Metadherin, a cell surface protein in breast tumors that mediates lung metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:365–74. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta GP, Nguyen DX, Chiang AC, et al. Mediators of vascular remodelling co-opted for sequential steps in lung metastasis. Nature. 2007;446:765–70. doi: 10.1038/nature05760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto M, Kikuchi H, Ohta M, et al. TSU68 prevents liver metastasis of colon cancer xenografts by modulating the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9754–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.