Convincing evidence suggests that females and males are different in regard to susceptibility to both infectious and non-infectious diseases. Sex and gender influences the severity and outcome of several infectious diseases, including leptospirosis, tuberculosis, listeriosis, Q fever, avian influenza and SARS.1–3 Sex and gender differences have been observed in vaccine response and antibiotic treatment regimens.4,5 Although the exact mechanisms are largely unknown, behavioural as well as biological variances are likely to contribute to these differences.

Collecting and sharing data on sex during outbreaks is valuable in improving our understanding of its role on emerging infectious diseases, including Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Mainstreaming sex and gender into surveillance and outbreak investigations is a priority under the Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases (2010).6 Identifying sex and gender differences may guide response to public health emergencies ultimately minimizing the health, economic and social impact of emerging diseases.

The 2015 outbreak of MERS in the Republic of Korea has been the largest health-care-associated outbreak of MERS outside the Saudi Arabia and the rest of Middle East. As of 30 June 2015, there have been 183 MERS cases reported since the first imported case on 20 May 2015, including one from China. To understand possible variances of the susceptibility and transmission of the disease, we conducted a sex-based analysis of the data.

Data on demographic characteristics and type of exposure for laboratory-confirmed MERS cases reported in the Republic of Korea from 20 May to 30 June 2015 were obtained from the publically available line list.7 For single proportions, the one-sample z test was used, and the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare quantitative variables. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

For the MERS cases from the Republic of Korea, the median age for males was 55 years (range 16–87 years, n = 110); for females, it was 57 years (range 24–84 years, n = 73) (P = 0.522). The predominance of male cases in the Republic of Korea (60%) was similar to that observed in the Middle East, where has been related to more frequent occupational exposure to camels (the putative animal reservoir of MERS-CoV).8,9 A similar predominance of male cases was also observed in nosocomial outbreaks in the Middle East10; however, reasons for this have not been investigated. For the Republic of Korea outbreak, exposure to camels was unlikely for the primary cases.

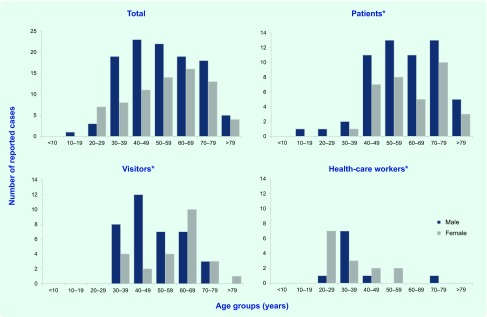

When the MERS cases were stratified by age and sex, the highest numbers were observed for males aged 40–49 years (23 males compared with 11 females; P = 0.036) (Fig. 1). This age and sex distribution was different from the overall Korean population that has a large proportion of young and middle-aged adults in both sexes.11 However, the source population for the MERS cases (i.e. population exposed at hospitals) might be different from the general population. Although the sex ratio among MERS cases appeared biased towards males, there was some evidence – as shown below – that more females were exposed. Stratification by type of exposure, including hospital patients (n = 92), hospital visitors (n = 61) and health-care workers (HCW; n = 24) (six cases with unknown or undefined exposure were not included) revealed further details (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Number of reported MERS-CoV cases in total, by age group, sex and type of exposure, Republic of Korea, 20 May to 30 June 2015 (n = 183)

* Six cases where type of exposure was unknown and the index case were excluded.

First, the male-to-female ratio was similar for cases exposed as hospital patients and hospital visitors (1.70:1 and 1.75:1, respectively); the opposite was seen for HCW (ratio 0.7:1). Although the preponderance of HCW female cases might be explained by more females working in the health-care sector, the number of female HCW is at least three times that of male HCW.12 Therefore, if the risk of infection is not associated with sex, then a male-to-female ratio of 0.3:1 or below would be expected.

Second, the age distribution between the sexes was comparable for both patients and HCW; among visitors, the age distribution varied between males and females. For visitors, while most of the younger cases were males, the age group wuth the highest number of female cases was 60–69 years. One possible reason for this might be differences in perceptions and behaviours related to hygienic measures as observed in the influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in the Republic of Korea in 200913; however, the overall predominance of males among visitors is enigmatic as it has been shown that females in the Republic of Korea are more likely to care for their sick relatives.14 That most cases were males also suggests that more visitors (i.e. spouses) and subsequent cases were female.

Another possible explanation for the excess of male cases could be differences in health-seeking behaviour and access that resulted in subsequent surveillance bias with underdiagnosing and underreporting of female patients. However, this seems unlikely as active surveillance and case finding were conducted in this outbreak. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that medical care utilization in the Republic of Korea is considerably higher in females.15

A predominance of male cases has also been documented in patients with pneumonia caused by influenza A(H1N1) infections, and smoking was the most relevant and independent risk factor during the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in the Republic of Korea.16 While middle-aged males in the Republic of Korea have the highest prevalence of smoking in all Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries (40%), females have one of the lowest (6%).17 However, detailed case-based clinical data are necessary to provide more insight into the possible correlation of smoking and MERS-CoV infection.

There are several limitations to this analysis which have to be considered. We provide only a preliminary analysis of the available data to generate initial hypotheses about sex-specific differences for the MERS outbreak in the Republic of Korea. Case-based data on other potential risk factors were not available. Also, denominators for the exposure groups by sex were unknown. However, this initial assessment could have immediate implications for disease prevention and control. In addition to more targeted prevention measures, future clinical and epidemiological studies on MERS should include sex and gender-specific analysis, as comparing groups with different proportions of male or female subjects may introduce confounding effects.

This analysis of the outbreak of MERS in the Republic of Korea revealed relevant sex-specific differences. While this preliminary analysis cannot provide a complete picture of sex and MERS, it raises awareness among public health professionals and health-care providers to recognize sex as a relevant determinant in the epidemiology of MERS. Further epidemiological and virological investigations are needed to better understand the nature of this disease as many unknowns remain, including those related to sex and gender.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the MERS data. Other members of the WHO Western Pacific Region MERS Event Management Team: Takeshi Kasai, Kidong Park, Byung Ki Kwon, Kotaro Tanaka, Helena Humphrey, Jan-Erik Larsen, Warrick Junsuk Kim, Charito Aumentado, Yuji Jeong, David Koch, Raynal C Squires, Qui Yi Kyut, Cindy Hsin Yi Chiu, Alisson Clements-Hunt, Shang Mei, SeongJu Choi, Sung Kyu Chang, Myeongshin Lee, Motoi Adachi, Hyobum Jang, Souphantsone Houatthongkham, Peter Hoejskov.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Jansen A, et al. Sex differences in clinical leptospirosis in Germany: 1997–2005. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44:69–72. doi: 10.1086/513431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlberg J, Chong DS, Lai WY. Do men have a higher case fatality rate of severe acute respiratory syndrome than women do? American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:229–31. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arima Y et al, World Health Organization Outbreak Response Team Human infections with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in China: preliminary assessments of the age and sex distribution. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal. 2013;4:1–3. doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2013.4.2.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Lunzen J, Altfeld M. Sex differences in infectious diseases-common but neglected. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;209(Suppl 3):S79–80. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giefing-Kröll C, et al. How sex and age affect immune responses, susceptibility to infections, and response to vaccination. Aging Cell. 2015;14:309–21. doi: 10.1111/acel.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases (2010). Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2011. http://www.wpro.who.int/emerging_diseases/APSED2010/en/ accessed 17 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.MERS-CoV cases in the Republic of Korea as of 14/7/2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ accessed 15 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Update on MERS-CoV transmission from animals to humans, and interim recommendations for at-risk groups. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/MERS_CoV_RA_20140613.pdf?ua=1 accessed 15 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller MA, et al. Presence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide, cross-sectional, serological study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2015;15:559–64. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oboho IK, et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah–a link to health care facilities. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:846–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Korea. http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/index.action accessed 15 July 2015.

- 12.Jung SI, et al. Sero-epidemiology of hepatitis A virus infection among healthcare workers in Korean hospitals. The Journal of Hospital Infection. 2009;72:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JH, et al. Perceptions and behaviors related to hand hygiene for the prevention of H1N1 influenza transmission among Korean university students during the peak pandemic period. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10:222. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhee YS, et al. Depression in family caregivers of cancer patients: the feeling of burden as a predictor of depression. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:5890–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chun H, et al. Explaining gender differences in ill-health in South Korea: the roles of socio-structural, psychosocial, and behavioral factors. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2008;67:988–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi SM, et al. The impact of lifestyle behaviors on the acquisition of pandemic (H1N1) influenza infection: a case-control study. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2014;55:422–7. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.2.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health Statistics OECD. 2014 How does Korea compare? Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentM; 2015. www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Briefing-Note-KOREA-2014.pdf accessed 15 July 2015. [Google Scholar]