Abstract

Background

Residency is an intense period. Challenges, including burnout, arise as new physicians develop their professional identities. Residency programs provide remediation, but emotional support for interns is often limited. Professional development coaching of interns, regardless of their performance, has not been reported.

Objective

Design, implement, and evaluate a program to support intern professional development through positive psychology coaching.

Methods

We implemented a professional development coaching program in a large residency program. The program included curriculum development, coach-intern interactions, and evaluative metrics. A total of 72 internal medicine interns and 26 internal medicine faculty participated in the first year. Interns and coaches were expected to meet quarterly; expected time commitments per year were 9 hours (per individual coached) for coaches, 5 1/2 hours for each individual coachee, and 70 hours for the director of the coaching program. Coaches and interns were asked to complete 2 surveys in the first year and to participate in qualitative interviews.

Results

Eighty-two percent of interns met with their coaches 3 or more times. Coaches and their interns assessed the program in multiple dimensions (participation, program and professional activities, burnout, coping, and coach-intern communication). Most of the interns (94%) rated the coaching program as good or excellent, and 96% would recommend this program to other residency programs. The experience of burnout was lower in this cohort compared with a prior cohort.

Conclusions

There is early evidence that a coaching program of interactions with faculty trained in positive psychology may advance intern development and partially address burnout.

What was known and gap

Residency is an important but stressful period in physicians' professional development, with limited emotional support. Data are lacking on the efficacy of professional development coaching for residents.

What is new

A program to support interns' professional development and identity formation through positive psychology coaching.

Limitations

Lack of a comparison group, small sample size, and single specialty program reduce generalizability.

Bottom line

Early evidence suggests intern development may be advanced, and burnout was partially addressed through the coaching program.

Editor's Note: The online version (32.5KB, docx) of this article contains an overview of the 2 faculty development coach training sessions, the intern mentor preference form, guides to sessions 1 through 4, a table of anticipated time commitments for participants, and demographic information.

Introduction

The transition from medical student to resident is one of the most challenging transformational periods in physicians' development. During this time, their lack of experience, long work hours, and work compression collide.1,2 Research suggests that exaggerated stress responses can emerge under these circumstances.3,4 Interns have little time to assimilate all that they are learning and also manage their emotional development. This period contributes to a burnout prevalence as high as 81% by late internship year, as determined in a multi-institution study,5 suggesting that regular feedback and early identification of personality style may help combat burnout.

Feedback obtained through traditional evaluations is often inadequate for helping residents understand their development.6,7 Caverzagie et al8 found that residents often focus only on patient care and medical knowledge, and may disregard feedback on their development in the other competencies (systems-based practice, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal communication, and professionalism). Another study showed that lower-performing residents do not readily identify weaknesses and overestimate their abilities.9 In contrast, higher-performing residents often underestimate their skills in core competency areas. This mismatch can produce blind spots and interfere with optimal professional development. Providing a safe and facilitated opportunity for residents to incorporate reflection into their experiences may enhance their growth as physicians.10

Programs for residents who need remediation have been described in published reports.11–13 This approach, however, may neglect residents who are meeting or exceeding expectations, but may not reach their optimal potential. Research has shown that involving all residents in a structured program was useful in developing awareness of academic accomplishment, interpersonal communication skills, and professional behaviors.14 Webb et al15 attempted individualized emotional intelligence coaching for second-year residents, but none of the participants completed the program, and there were no changes in residents' self-ratings.

Advisors, preceptors, and core faculty may form longitudinal relationships with residents, but their dual evaluator/advisor role presents a conflict for residents who may be hesitant to share their true experiences and perspectives. Opportunities to interact with residents in a nonevaluative role are limited, and finding faculty mentors can be challenging given competing commitments.

This article reports on our experiences in creating a professional development coaching program for internal medicine interns based on the principles of positive psychology. Positive psychology is the study of the conditions and processes that contribute to the optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions.16 Positive psychology coaching uses a strengths approach that emphasizes engagement, meaning, and accomplishment.17 This approach has been suggested as a way to strengthen professional skills of physicians, to combat burnout, and to improve their quality of life. To date, there are few data on the efficacy of coaching programs for physicians. We report on program development activities, coach selection and training, and interns' perceptions of their experiences.

Methods

We implemented the Professional Development Coaching Program during the 2012–2013 internship year.

Goals and Program Development

Program leadership identified the lack of clearly defined support and guidance in internship. The Professional Development Coaching Program was created to establish a safe environment for interns to reflect on their performance, honestly discuss their professional development, and identify and understand how to optimize their strengths to overcome challenges and stressors. Our strengths-based coaching model followed the principles of positive psychology and was designed to be nonevaluative, learner-driven, and egalitarian.18

Faced with the decision whether to randomize half of the cohort to the new coaching intervention or to establish the program for the entire group, we determined that it would be too long before we had actionable data from a randomized controlled study. A decision was made to develop this program for all interns and to use a published historical reference on burnout as a control. Interns were connected with an independent faculty member who could address issues that residents typically face, but often do not feel free to share with the resident's evaluative faculty. Faculty coaches were trained in positive psychology and connected with a group of like-minded educators through faculty development.

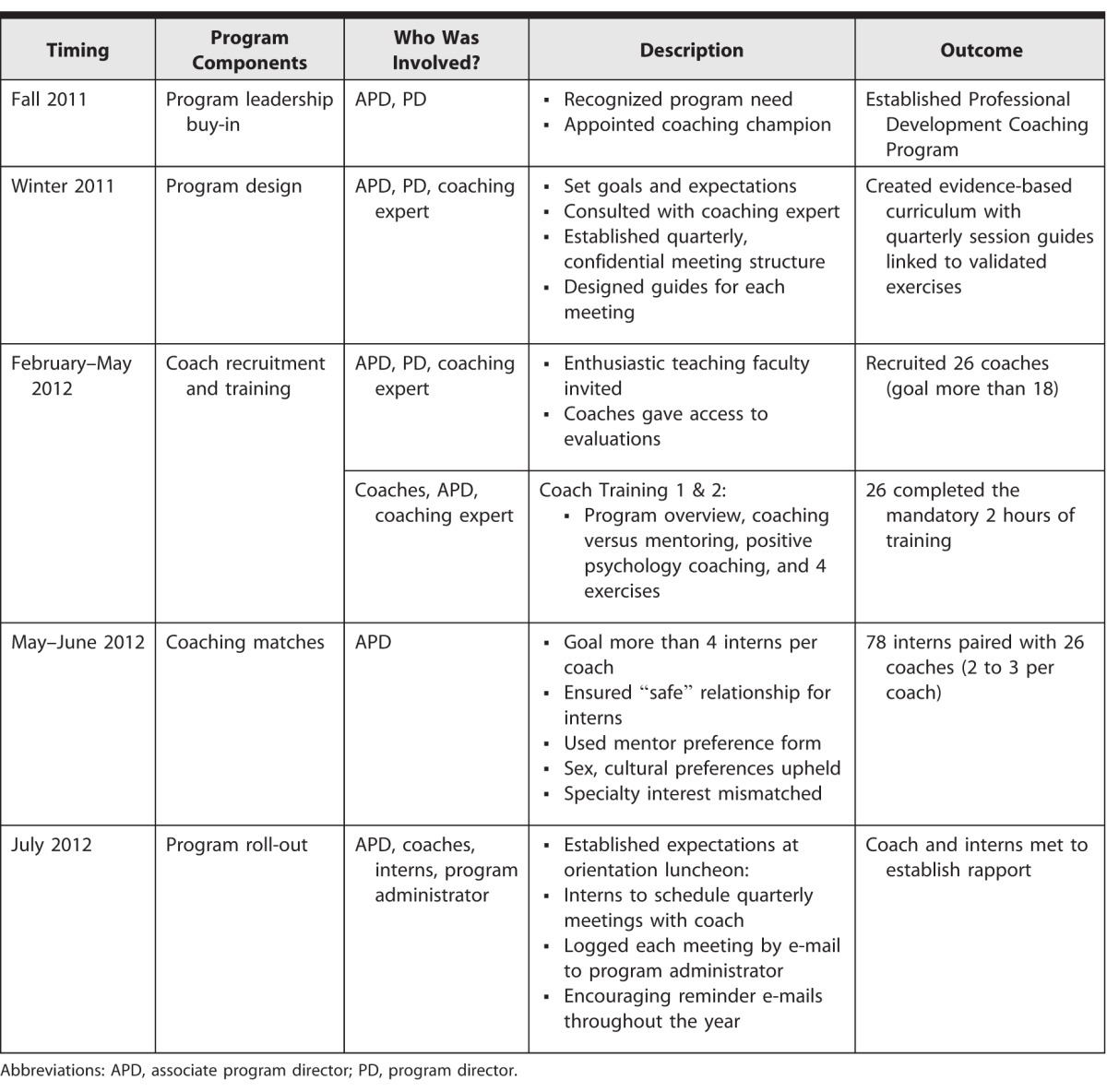

One associate program director was assigned responsibility for the development, structure, and implementation of the coaching program, and will be referred to as the coaching program director (CPD). The CPD collaborated with a positive psychology coaching expert to design and execute coach training and to provide coaching support to faculty coaches. This process is detailed in table 1, which describes a step-by-step approach and associated timeline. We also quantified and outlined the expected coach hours per trainee, hours per intern coached, and the CPD time commitment for program implementation and oversight (provided as online supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Professional Development Coaching Program Implementation Timeline, Key Stakeholders, Description of Activities, and Measured Outcomes

Participants

Coaches for the program were members of the department of medicine teaching faculty. Potential faculty coaches were identified from the core faculty, former chief residents, graduates of the residency program, preceptors, and other enthusiastic teaching faculty. Program directors and senior career mentors were excluded to avoid role conflict. In the first program year, 26 coaches were recruited. The individuals coached were all 72 interns in the program.

Coach-Intern Matching

Trained coaches were assigned 2 to 3 interns prior to orientation in June 2012. To pair interns with their coaches, the CPD used a preference form typically used to pair incoming interns with faculty mentors. The form is available as online supplemental material. Career interests were intentionally mismatched to allow for safe exploration and honest discussion without concern for future career impact. Coaches and interns met during internship orientation, when the program was introduced and expectations were reviewed.

Coach Training

All 26 coaches participated in 2 hours of training. Coaches were introduced to core concepts of developmental coaching and positive psychology,19–23 using hands-on experience of coaching exercises (provided as online supplemental material). Strategies for managing particular situations such as poor intern performance and unrealistic self-assessment were reviewed.

Through positive psychology exercises, coaches began to focus on active listening, using questions to promote self-reflection, and articulating positive emotions and strengths as opposed to emphasizing negative emotions and weaknesses. At the conclusion of training, it was acknowledged that uncertainty in their coaching skills was expected and normal. Coaches were reassured that their prior patient care experiences in motivational interviewing, helpful guides, and training-focused e-mail updates throughout the year would support them.

Coaching Sessions

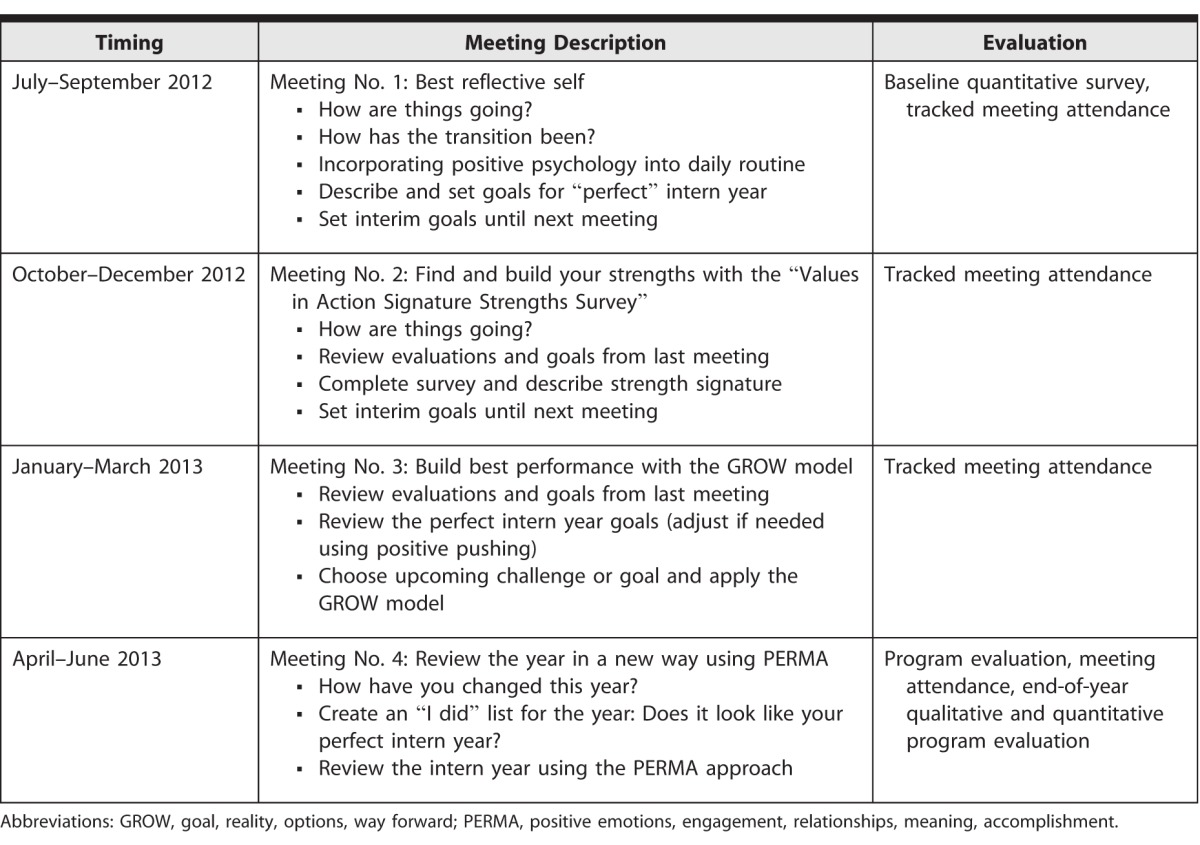

Interns were expected to meet with their coaches quarterly (table 2). These meetings were held at a location of their choice and were expected to last 40 minutes on average. Session guides were created for each meeting, along with sample questions to engage the resident in discussion and descriptors of the positive psychology exercise linked to that meeting. These guides were accessible to coaches through Dropbox, an online file-sharing program, and are available as online supplemental material. Coaches were given access to the evaluations of the interns they coached through the program's online evaluation system. To foster participation, monthly reminders to schedule coaching meetings were sent by the CPD to coaches and interns. All discussions in coaching meetings were strictly confidential, unless the coach was concerned for the safety of the intern or his or her patients.

TABLE 2.

Coaching Program Throughout Academic Year With Timing and Goals of Meetings Linked to Evaluation Timeline

The program and its evaluation were declared exempt by our institution's Institutional Review Board.

Program Evaluation

We performed both an objective and a subjective evaluation of the program in its first year. We timed initial survey data collection so that interns would have at least 3 months of work experience and presumably 1 coaching meeting. Quantitative data were collected in the first and fourth quarters of the program.

Online quantitative surveys were conducted with e-mail recruitment. Incentives were offered to survey respondents in the form of hospital dining facility gift cards. The primary process and outcome measurements collected from interns in the first year of evaluating the program included (1) experience with the program, as well as the use of coaching exercises and coach-intern interactions; (2) professional development goals and activities; (3) professional interactions and working relationships with colleagues; and (4) assessment of professional accomplishment and emotional exhaustion as measured in the Maslach Burnout Inventory.24 Measurements of program experience, professional development, and interactions were designed based on tools previously developed for health workforce studies.25,26

Results

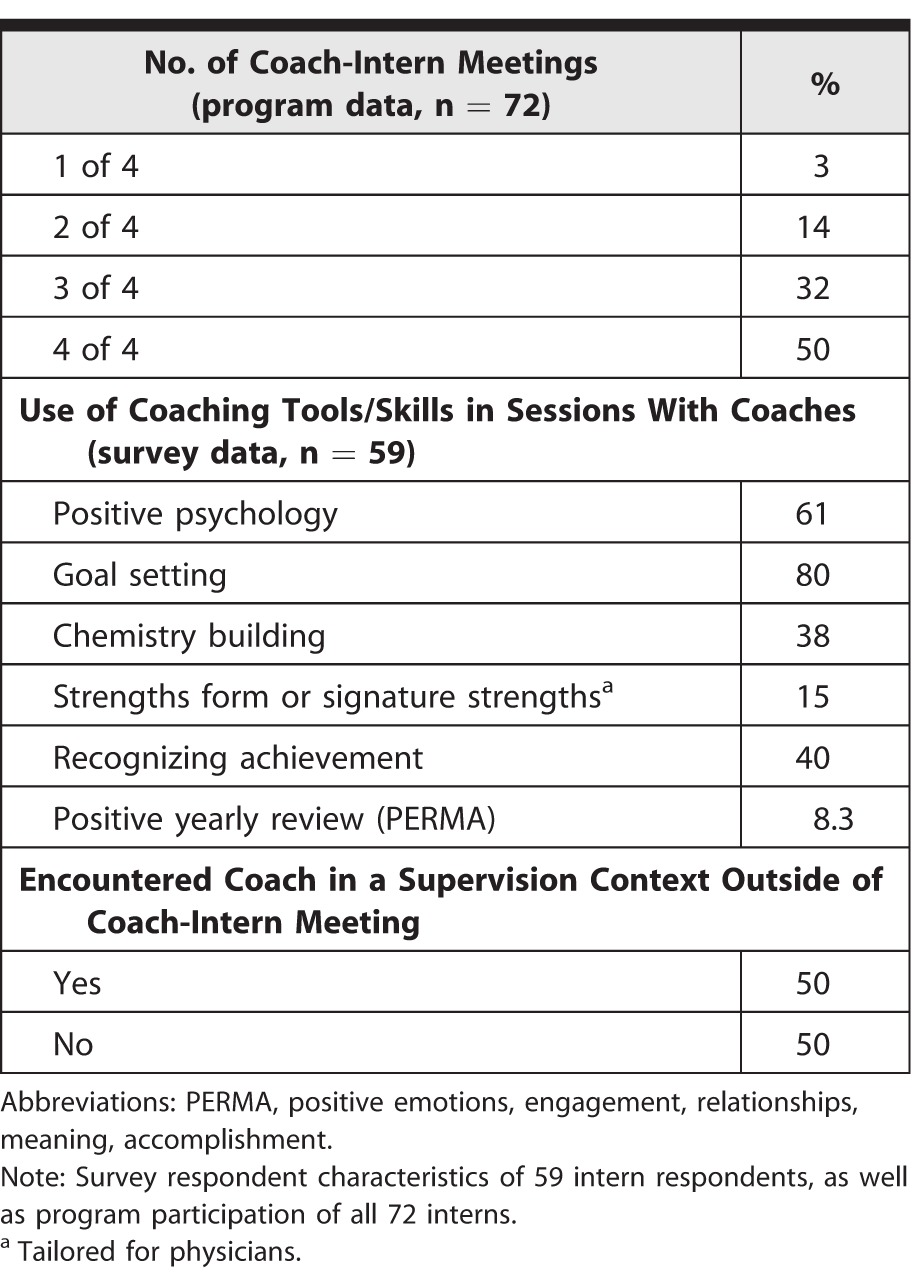

Nearly all (99%, 71 of 72) interns met with their coaches at least once; 50% (36 of 72) met all 4 times (table 3). Small sample sizes precluded detailed analysis of the impact of the number of meetings on outcomes.

TABLE 3.

Program Participation

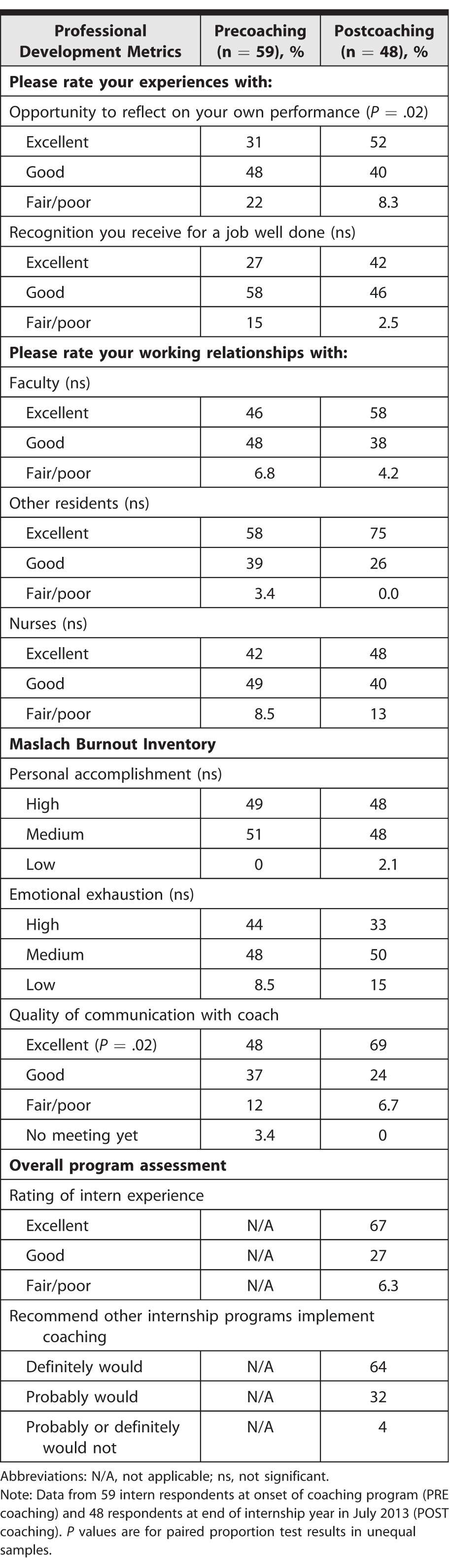

We assessed program experience in presurveys and postsurveys (table 4). Twenty-six coaches and 72 interns were eligible for participation in wave 1 quantitative surveys, conducted in September and October 2012. Twenty-four coaches and 72 interns were eligible for wave 2, conducted in May 2013. Two coaches left the institution, and their interns were reassigned. In wave 1, 100% (26 of 26) of the coaches and 82% (59 of 72) of the interns participated; in wave 2, 92% (22 of 24) of the coaches and 67% (48 of 72) of the interns participated. Due to unequal responses for the 2 waves, tests of the difference in proportion in unequal pairs were used to compare group differences. At year-end, 94% (45 of 48) of interns rated the coaching program as good or excellent; 96% (46 of 48) would recommend this program to other residencies; and 65% (31 of 48) rated the quality of communication with their coach as “excellent.”

TABLE 4.

Quantitative Pre- and Postcoaching Program Experience Data

Program activities stressed self-assessment of skills and strengths in both patient care and interpersonal communication. We observed significant differences among interns in the time devoted to self-reflection and communication with the coach.

In the year prior to the program, our institution participated in a multisite study assessing emotional exhaustion among interns.5 Baseline data in July 2011 showed that 12% (6 of 49) of the interns scored high on the emotional exhaustion subscale. Follow-up data from July 2012 indicated that 47% (23 of 49) of the interns had high emotional exhaustion scores at the end of their intern year. In contrast, our initial measurements for interns after 3 months of internship showed that 44% (26 of 59) of interns scored high on emotional exhaustion compared to 33% (16 of 48) near the end of the intern year. Our pre-post changes were not significant in the samples of these sizes. Personal accomplishment scores were unchanged from our pre- and postsurveys.

Despite efforts to match coaches and interns outside of direct supervisory relationships, 50% (24 of 48) of interns reported that they had some supervisory relationships with their coaches. This feedback was incorporated into coach training on how to better manage these interactions and how we matched interns with their coaches.

Discussion

Our coaching program is the first of its kind to focus on all interns in a medicine residency program, regardless of performance, with a strengths orientation model built on evidence-based positive psychology. In its first year, participation was high: 82% of interns met with their coaches at least 3 times. Despite variable use of coaching exercises, the overall assessment of the program was strongly positive.

Our initial evaluation highlighted some areas for improvement to address in the second year. It showed that coach preparedness was variable, and that the approach to the coaching interactions was inconsistent. Ongoing training, including development and use of training videos, will be helpful in standardizing the approach.

The time and financial costs of this program were minimized purposefully to increase program director buy-in and ensure sustainability. The CPD also functions as an associate program director, and grant funds were used mostly for program evaluation. Faculty time was voluntary, which may represent the recognized need for faculty buy-in and commitment to the program. Our positive psychology coaching expert volunteered her time to help design the program.

For other programs that wish to build a similar coaching program at their institution, we have provided our curricular materials as online supplemental material, and we are providing education through professional society meetings. We recognize that not all programs have the ability to implement this type of program. That being said, we do believe that incorporating positive psychology coaching tools and techniques into existing advising and mentoring programs would be beneficial.17

There are a few limitations to our approach. First, there was no comparison group. Second, given the size of this cohort, the analysis of our data is descriptive in nature; the size of the study group precluded multivariate analyses at this phase. Third, generalizability of the study findings to other internal medicine programs is limited due to use of a 1-year cohort at a large university-based program.

Based on our experience in the first year, our professional development coaching program was expanded to a 3-year curriculum, with the expectations that coaches work with their assigned interns throughout their residency and receive training each year. The next steps to determine the value of this overall program will be a 3-year qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the curriculum, including the impact of the program on coaches and residents.

Conclusion

The addition of a coaching program, separate from performance evaluation and career advising and based on positive psychology methods, was feasible and highly acceptable to internal medicine interns and selected faculty coaches. Interns reported less emotional exhaustion and burnout than reported by the previous year's cohort.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Kerri Palamara, MD, is Primary Care Program Director, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital; Carol Kauffman, PhD, ABPP, is Founder/Executive Director, Institute of Coaching, Harvard Medical School; Valerie E. Stone, MD, MPH, is Chair of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Mount Auburn Hospital; Hasan Bazari, MD, is Director of the Swartz Initiative, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital; and Karen Donelan, ScD, EdM, is Senior Scientist, Mongan Institute for Health Policy, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Funding: The Josiah H. Macy Foundation provided $35,000 of funding through a President's Grant to support the establishment and operation of this program.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

The Professional Development Coaching Program model was presented in part during workshops at the Society for General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Denver, Colorado, April 2013, as well as at their Annual Meeting in San Diego, California, April 2014; and at the Association for Program Directors in Internal Medicine Spring Meeting in Orlando, Florida, April 2013, and their fall meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana, October 2013. Additionally, this program model was presented as an invited plenary at the Association for Program Directors in Internal Medicine Spring Meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, April 2014, and at an invited precourse at their Spring Meeting in Houston, Texas, April 2015.

References

- 1.Gordon GH, Hubbel FA, Wyle FA, Charter RA. Stress during internship: a prospective study of mood states. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1(4):228–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02596188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin AR. Stress in residency: a challenge to personal growth. J Gen Intern Med. 1986;1(4):252–257. doi: 10.1007/BF02596195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster E, Biery N, Dostal J, Larson D. RAFT. (Resident Assessment Facilitation Team): supporting resident well-being through an integrated advising and assessment process. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):731–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux;; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ripp J, Babyatsky M, Fallar R, Bazari H, Bellini L, Kapadia C, et al. The incidence and predictors of job burnout in first-year internal medicine residents: a five-institution study. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1304–1310. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green ML, Aagaard EM, Caverzagie KJ, Chick DA, Holmboe E, Kane G, et al. Charting the road to competence: developmental milestones for internal medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(1):242–245. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caverzagie KJ, Iobst WF, Aagaard EM, Hood S, Chick DA, Kane GC, et al. The internal medicine reporting milestones and the next accreditation system. Ann Int Med. 2013;158(7):557–560. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caverzagie KJ, Shea JA, Kogan JR. Resident identification of learning objectives after performing self-assessment based upon the ACGME core competencies. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1024–1027. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipsett PA, Harris I, Downing S. Resident self-other assessor agreement. Arch Surg. 2011;146(8):901–906. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quirk M. Intuition and Metacognition in Medical Education: Keys to Developing Expertise. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co;; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu JS, Siewert B, Boiselle PM. Resident evaluation and remediation: a comprehensive approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):242–245. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00031.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratan RB, Pica AG, Berkowitz RL. A model for instituting a comprehensive program of remediation for at-risk residents. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1155–1159. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818a6d61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao DC, Wright SM. The challenge of problem residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):489–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogunyemi D, Solnik MJ, Alexander C, Fong A, Azziz R. Promoting residents' professional development and academic productivity using a structured faculty mentoring program. Teach Learn Med. 2010;22(2):93–96. doi: 10.1080/10401331003656413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb AR, Young RA, Baumer JG. Emotional intelligence and the ACGME competencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(4):508–512. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00080.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gable S, Haidt J. What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev Gen Psychol. 2005;9(2):103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gazelle G, Liebschutz JM, Riess H. Physician burnout: coaching a way out. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):508–513. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3144-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachkirova T, Kauffman C. The blind men and the elephant: using criteria of universality and uniqueness in evaluating our attempts to define coaching. Coaching Int J Theory Res Pract. 2009;2(2):95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linley PA, Kauffman C. The meeting of the minds: positive psychology and coaching psychology. Coaching Psychol Rev. 2007;2:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheldon KM, Lyubomirsky S. How to increase and sustain positive emotion: the effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. J Posit Psychol. 2006;1(2):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson C, Seligman M. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;; 2004. pp. 625–642. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitmore J. Coaching for Performance: GROWing Human Potential and Purpose—The Principles and Practice of Coaching and Leadership. 4th ed. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seligman M. Flourish. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Publishing;; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maslach C, Schaufeli W, Leiter M. Job burnout. Ann Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buerhaus PI, Donelan K, Ulrich BT, Norman L, DesRoches C, Dittus R. Impact of the nurse shortage on hospital patient care: comparative perspectives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(3):853–862. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donelan K, DesRoches CM, Dittus RS, Buerhaus PI. Physician and nurse practitioner perspectives on primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1898–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.