Abstract

Background

The context for specialty residency training in pediatrics has broadened in recent decades to include distributed community sites as well as academic health science centers. Rather than creating parallel, community-only programs, most programs have expanded to include both community and large urban tertiary health center experiences. Despite these changes, there has been relatively little research looking at residents' experiences in these distributed graduate medical education programs.

Objective

A longitudinal case study was undertaken to explore the experiences of residents in a Canadian pediatrics residency program that involved a combination of clinical placements in a large urban tertiary health center and in regional hospitals.

Methods

The study drew on 2 streams of primary data: 1-on-1 interviews with residents at the end of each block rotation and annual focus groups with residents.

Results

A thematic analysis (using grounded theory techniques) of transcripts of the interviews and focus groups identified 6 high-level themes: access to training, quality of learning, patient mix, continuity of care, learner roles, and residents as teachers.

Conclusions

Rather than finding that certain training contexts were “better” than others when comparing residents' experiences of the various training contexts in this pediatrics residency, what emerged was an understanding that the different settings complemented each other. Residents were adamant that this was not a matter of superiority of one context over any other; their experiences in different contexts each made a valuable contribution to the quality of their training.

What was known and gap

While graduate medical education is increasingly requiring residents to spend time in community settings, resident experiences of these placements have not received much study.

What is new

A longitudinal study of pediatrics resident experiences suggests rotations in both an urban tertiary health center and community settings make valuable contributions to resident education.

Limitations

Small sample, single institution, and single specialty study limit generalizability; the study only assessed resident perceptions, not educational outcomes.

Bottom line

A hybrid pediatrics program combining an urban tertiary setting and community rotations offers residents a well-rounded experience.

Introduction

The context for specialty residency training has broadened in recent decades to include distributed community sites as well as academic health science centers (AHSCs).1 For some disciplines this is now a requirement. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada requires “2 to 6 dedicated blocks or 6 months of equivalent longitudinal community/rural pediatrics” during the first 3 years of pediatrics training.2 Community-based and AHSC-based training have been described as distinct, yet complementary, models of graduate medical education.3 Distributed programs have typically been considered in the context of their outcomes,4 social mission,5 or workforce dimensions.6,7 Rather than creating parallel community-only programs, most residency programs seem to have expanded to include both community and urban tertiary experiences, as indicated by descriptions of the introduction of community experiences to existing programs.8,9

From a resident perspective, augmentation would appear to be the more useful model, as the additional training contexts allow for a more comprehensive learning experience. There is evidence to indicate that residents require a broad range of experiences to be able to meet the requirements of competency-based programs.10

Despite these changes, residents' perceptions of their experiences in distributed programs have been little studied, although there is evidence to suggest that the human dimension of preceptor support and patient interactions is more important to residents than the physical nature of the training context or its organization.11–13 Resident perceptions can be a meaningful way to explore relational and contextual issues and to gain an understanding of how programs actually work. In this article, we explore the experiences of residents in a Canadian pediatrics residency program involved in a combination of large urban tertiary and regional hospital clinical placements.

Methods

We undertook a longitudinal case study14,15 that employed techniques from grounded theory16,17 to explore the experiences of pediatrics residents at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) in Canada. The program was launched in 2010 in partnership with the University of Ottawa in Canada, with NOSM pediatrics residents completing approximately half of their training at a University of Ottawa facility. We were unaware of any similar program models and wanted to explore several factors, including (1) the equivalence and difference in residents' clinical encounters and learning experiences at different sites; (2) the nature and substance of differences in resident experiences in diverse settings; and (3) whether improvements could be made to the program. To that end, we designed the study around the question, “What were the experiences of the residents as they moved between different clinical contexts, and how did these experiences reflect the nature of the training environment afforded by the program?”

Study Context

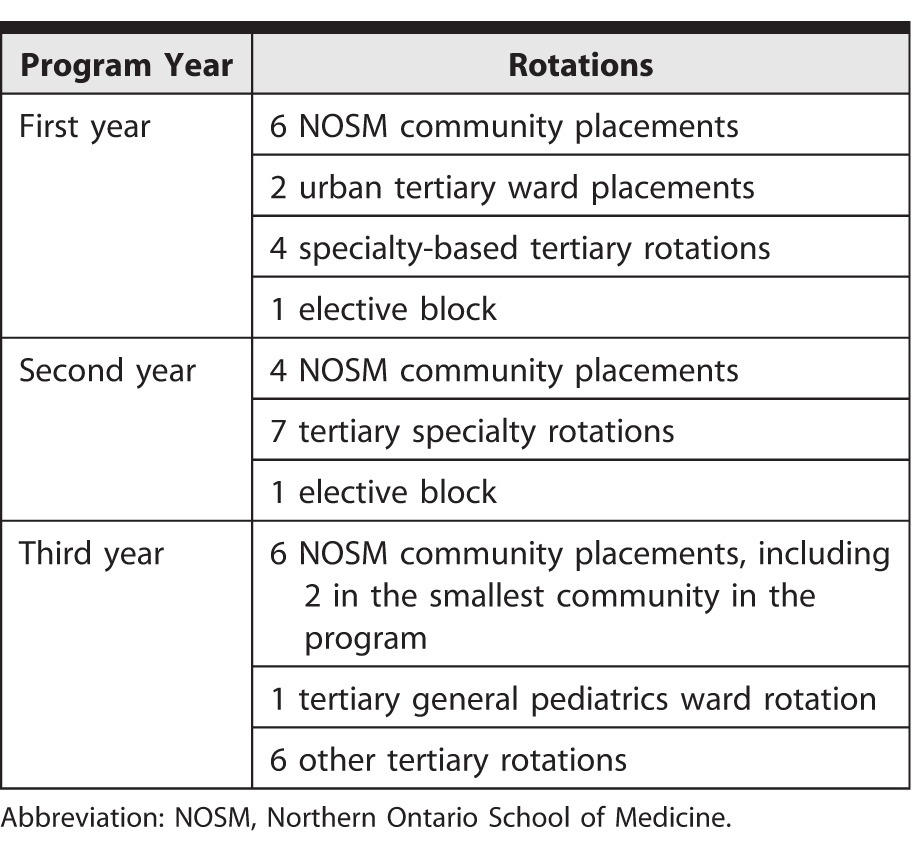

NOSM pediatrics residents rotate through a series of Northern- and Ottawa-based teaching blocks, with half of their training taking place in Ottawa and half in NOSM community settings. Rotation sites include 4 midsize communities across the North, while all rotations in Ottawa were at a single large urban tertiary pediatrics center (figure 1). Our focus was on the first 3 core years of pediatrics residency. The program was designed around 13 four-week block rotations per year, shown in table 1. Residents undertook their blocks at different times of the year and often were the only NOSM resident (or 1 of 2) in a block at any given time.

FIGURE 1.

Location of the Training Sites Involved in the Study

TABLE 1.

Rotations for the 3 Core Pediatrics Years

Data Collection

Our study used individual interviews, focus groups, and residents' logs of their clinical encounters using T-Res (Resilience Software Inc). We regularly reviewed the aggregate data from these logs and used them to structure and stimulate participant reflection in the interviews and focus groups.

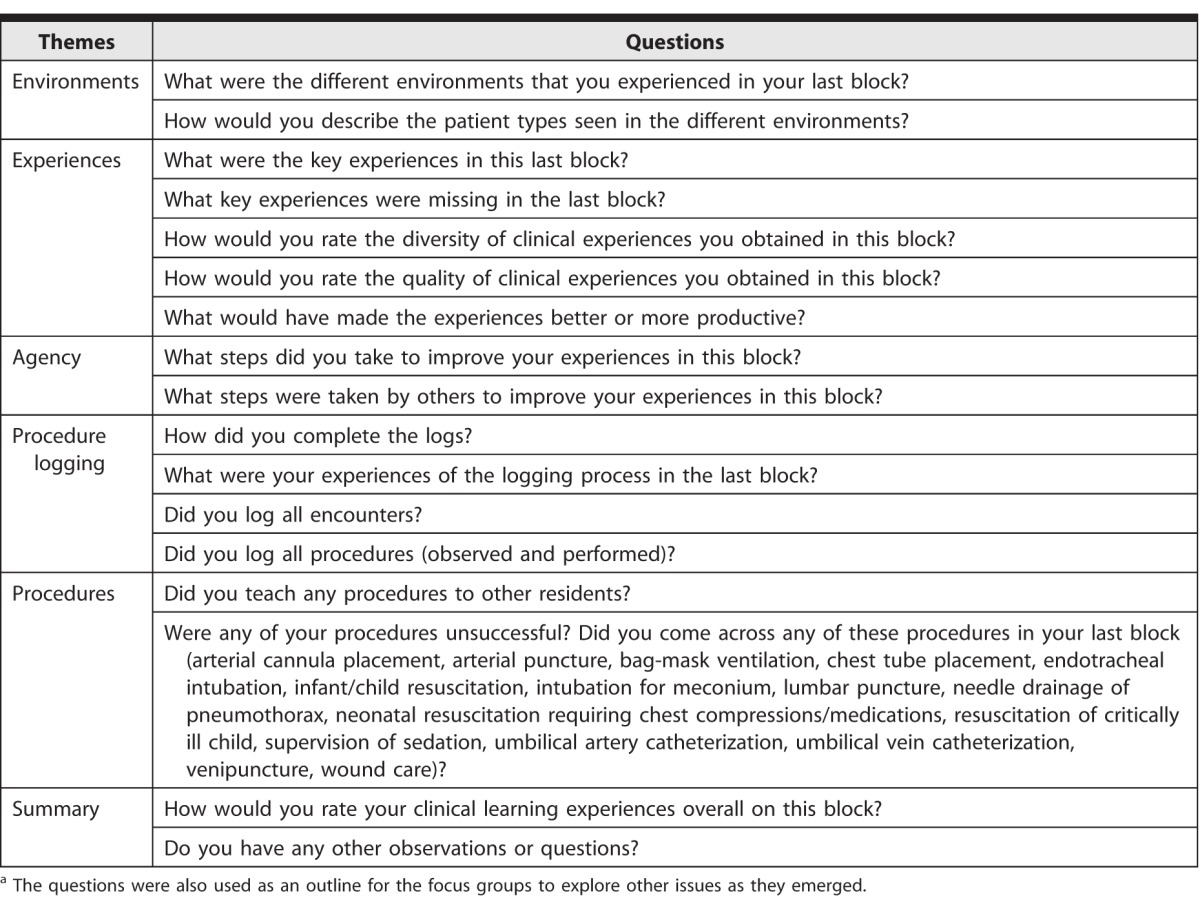

We conducted 1-on-1 semistructured telephone interviews with each resident after every block. We developed an initial semistructured interview script, and we periodically reviewed and amended it using feedback from the interviewer (A.P.) as well as residents' comments. The final form of the interview script is provided in table 2.

TABLE 2.

Telephone Interview Questionsa

We held focus groups once a year to explore emerging issues from the interviews and to reflect on provisional interpretations of the data from interviews and logs. We drew on the interview script as an outline for the focus groups and explored other issues as they emerged.

Participants

All residents in the incoming NOSM classes of July 2011 and July 2012 were invited, and all consented to participate. The Research Ethics Boards of both Laurentian University and Lakehead University approved the study.

Analysis

We employed techniques from grounded theory in analyzing the interview and focus group transcripts, including iterative sampling and theory building, and open coding (with no predetermined coding frame).16,17 We audio recorded the interviews and focus groups and transcribed them. Two reviewers (R.H.E. and A.P.) undertook the thematic analysis of the transcripts. First, the 2 reviewers independently conducted an open line-by-line coding of the transcripts using ATLAS.ti (Scientific Software Development GmbH). The 2 provisional coding frameworks were then compared and contrasted. Duplicate and similar concepts were merged, and the 2 coding frameworks were combined to create a single network-coding diagram, deriving higher-level codes from clusters and patterns in this network analysis.

The study team then discussed these higher-level codes, and made minor adjustments for language and clarity. We compared residents' clinical encounter log data (reported elsewhere) with findings from the thematic analysis as a validation step to look for common patterns in the types and frequency of encounters participants described and logged. We then held an additional resident focus group where our provisional findings were presented for participant comment and critique. We made a number of changes following this focus group meeting to ensure our interpretations accurately reflected residents' overall impressions of the program.

Results

The study ran from July 2011 to July 2013. All residents in the NOSM pediatrics program between 2011 and 2013 (n = 7 per year, total N = 14) participated in the study at some point in their training, although not all persisted with all aspects of the study. One resident withdrew after the first year and 3 residents declined to take part in the interviews. All active residents took part in the focus groups, which lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. Focus groups were held in January 2012 and January 2013.

Our analyses of the interview and focus group transcripts identified 6 high-level themes, described here.

Theme 1: Access to Training

There were essential differences in participants' perceptions of their access to patients during rotations. Participants experienced a reduced sense of hierarchy and less competition for training opportunities while on NOSM community blocks, highlighted by a resident's statement: “There is more of a hierarchy [in the tertiary setting].” Access to training opportunities with specialists was not perceived as better in the urban tertiary context. When a resident on a NOSM community block needed a telephone consult with a specialist at the tertiary center, he or she would usually be able to speak to the specialist directly, and this would more often than not provide some teaching as part of the discussion. When a resident on a tertiary rotation contacted a specialist in the same hospital, he or she would typically find themselves speaking to another resident who would provide treatment information, but little associated training. If a specialist made a patient visit, there was usually a delay between the initial consultation and the specialist arriving on the ward. By this time the resident would often be involved in other duties, resulting in the resident missing teaching opportunities arising from their interactions with the specialist.

Theme 2: Quality of Learning

The quality of learning was dependent on a number of relational factors, particularly the relationships residents developed with their preceptors and senior staff during their rotation. Participants noted that, while their role in treating patients differed according to context, they learned from all patients they encountered. This reflected a broader sense of complementarity in resident experiences. One participant indicated, “I think that [the tertiary setting] is more formal, but it is not necessarily better. Yes, there are more presentations . . . and they have resident-led teaching in the mornings, but I find in the northern sites you get a lot more informal teaching from your staff, so I wouldn't say that it is better but it is different.”

Theme 3: Patient Mix

Different patient populations resulted in different learning opportunities. One resident explained (about northern experiences), “You never know what is going to walk in the door . . . in the winter you just see bronchiolitis, whereas the next month you can have a whole bunch of different things so it is always just hit or miss.” Patient mix was not just a matter of northern community versus urban tertiary: all training locations had different patient profiles and offered residents access to a different mix of patients and diagnoses.

The experience of treating complex patients (those with multiple conditions or morbidities) differed by context. At NOSM community sites, the resident managed all aspects of patients' treatments, while tertiary specialists typically looked after specific aspects of treatment. One resident noted, “We get more of an overview of the complex patients up here. When you are [in the tertiary setting] and dealing with a complex patient it is often farmed out to the subspecialties.” Some patients were seen in both regional and tertiary contexts, such as when a northern patient was transferred to the tertiary center to receive treatment for an acute problem, and then returned to the regional hospital to manage his or her discharge into the community. Because the tertiary site was the referral center for a number of regional hospitals, it tended to have more complex patients than any of the regional sites.

Theme 4: Continuity of Care

Residents reported that a benefit of NOSM community rotations was the opportunity to see the same patient multiple times. One resident noted: “We get a lot of continuity that way with the outpatient clinics in the North which you never get in [the tertiary center].” The opposite was reported at the tertiary center: “Too often after discharge you never see [the patients] again.” Formative reviews of encounter logging data supported these observations: tertiary-based residents rarely had follow-up with their patients, while approximately a third of patients at regional centers were seen for follow-up.

Theme 5: Learner Roles

The team approach in the large urban tertiary setting meant that each member assumed a specific role, with little flexibility in its scope. Some junior residents initially found this difficult: “Do I have to check every single order that I want to do with somebody else before going ahead and doing it?” Residents in the tertiary setting were also required to take on a more managerial role than at regional sites. Teams were smaller in NOSM community contexts because there were fewer residents, preceptors, and medical students. This provided junior residents with more responsibility and allowed for more autonomy as their preceptors gained an appreciation of skill level at an earlier stage through more frequent interactions and continuity, at least in the first year of the program. The amount of autonomy given depended on preceptors getting to know their residents' abilities and comfort levels; these occurred more readily in smaller centers because of more frequent and direct interactions.

Theme 6: Residents as Teachers

Residents valued opportunities to teach others. One resident stated, “It forces me to learn a lot more about a topic. It gets you comfortable in front of a group teaching [them].” Another said, “It was a transition to a more senior role. Where if I was discussing a patient I would be expected to discuss current guidelines or the different pathophysiology behind the disease classes and receive questions from medical students to help to teach them.” There were many opportunities in the tertiary setting for NOSM residents to teach other residents and medical students. Resident teaching opportunities were less common in NOSM community sites because medical students and junior residents were not always present.

Discussion

Our exploration of pediatrics residents' perceptions of the 2 learning environments in a hybrid program revealed remarkable differences and a sense of the complementary nature of the 2 different training contexts. While the program had been established to ensure that regional experiences combined with those at a large urban tertiary site would encompass the required training for a pediatrician, the nature of learning, as well as the case mix residents were exposed to, differed among the locations and within the given location. Learning at the same site differed depending on the time of year, the teaching staff, the presence or absence of other students or residents, and the nature of the organizational culture.

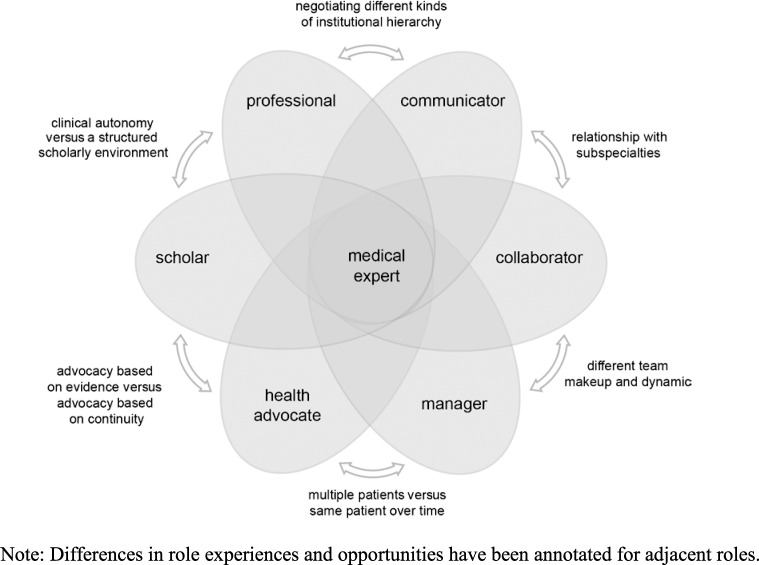

A useful way to look at this is in terms of the broad development of CanMEDS18 roles (Communicator, Collaborator, Manager, Medical Expert, Health Advocate, Professional, and Scholar) through exposure to different contexts. NOSM community sites and the tertiary center were complementary in addressing different aspects of the CanMEDS roles (figure 2). One resident said of the Manager role: “There are different types of managerial skills that you are learning in the northern setting and the [tertiary] setting. Again not more or less of one, just different.” Another said of the Health Advocate role: “Often they [NOSM] might require a bit more health advocacy when there are limited resources, but you have to advocate for your patients as well in [the tertiary setting] . . . for them to be seen . . . for follow-up care.” Overall, NOSM community experiences were perceived as providing more opportunities for developing the Communicator, Professional, and Health Advocate roles, while the large urban tertiary setting was seen as providing more opportunities for developing the Manager, Scholar, and Collaborator roles. Residents were adamant that this was not a matter of superiority of one context over any other. The experiences afforded by the different contexts were complementary: each was a valuable contribution to the quality of their training.

FIGURE 2.

Complementary Strengths of Regional and Urban Learning Environments for Pediatrics Residents Mapped to CanMEDS Intrinsic Roles

Given the paucity of similar studies, it is hard to draw direct parallels between this study and others. Our findings, however, echo other studies11–13 that showed that residents valued their relationships with peers, seniors, and preceptors, and the complementarity of diverse training contexts. Our findings also reflect the recommendations of the Future of Medical Education in Canada Postgraduate Project,19 with respect to experience in diverse learning and work environments, effective integration and transitions, and how skills acquired in one setting can be recognized in other environments.

Our study has a number of limitations. Despite the extended duration of the study and the high levels of participation, the small number of residents in the NOSM pediatrics program limits the generalizability of our findings. This study also is bound to the contexts in which it took place, and its generalizability is limited until this model can be explored in other contexts and programs. This study could be a starting point from which such research can be developed, exploring the applicability of our thematic model to other contexts.

Conclusion

Our longitudinal study of residents' experiences of a hybrid pediatrics residency program in which residents spend half of their time training in an urban tertiary setting and the other half in a variety of community settings highlights the complementary nature of the different training contexts and their contributions to a well-rounded educational experience. Our findings have been reflected in a more recent (and successful) accreditation review of the program that commended the strengths of this hybrid approach. For general pediatrics training it appears that a hybrid model can represent the best of both worlds.

Footnotes

Maureen Topps, MBChB, was Associate Dean, Postgraduate Medical Education, Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, and is now Associate Dean, Postgraduate Medical Education, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada; Rachel H. Ellaway, PhD, was Assistant Dean, Curriculum and Planning, Northern Ontario School of Medicine, and is now Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada; Tara Baron, MD, is Director, Pediatrics Residency Program, Northern Ontario School of Medicine; and Alison Peek, MSc, is Research Associate, Northern Ontario School of Medicine.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

An outline plan for this study was presented at the International Conference on Residency Education in Ottawa and at the MUSTER Conference in Barossa in 2010. Some aspects of this study were presented at the Association for Medical Education in Europe meeting in Milan and the International Conference on Residency Education in Toronto in 2014.

The authors would like to thank the University of Ottawa for its invaluable support of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine Pediatrics Program.

References

- 1.Woollard R. Many birds with one stone: opportunities in distributed education. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):222–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Specific Standards of Accreditation for Residency Programs in Pediatrics. 2008 version 1.0 [editorial revision May 2013] Ottawa, Canada: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada;; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates J, Frost H, Schrewe B, Jamieson J, Ellaway R. Distributed education and distance learning in postgraduate medical education. The Future of Medical Education in Canada Postgraduate Project. 2011 In. https://www.afmc.ca/pdf/fmec/12_Bates_Distributed%20Education.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worley P, Esterman A, Prideaux D. Cohort study of examination performance of undergraduate medical students learning in community settings. BMJ. 2004;328(7433):207–209. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7433.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovato C, Bates J, Hanlon N, Snadden D. Evaluating distributed medical education: what are the community's expectations? Med Educ. 2009;43(5):457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schofield A, Bourgeois D. Socially responsible medical education: innovations and challenges in a minority setting. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):263–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnus JH, Tollan A. Rural doctor recruitment: does medical education in rural districts recruit doctors to rural areas? Med Educ. 1993;27(3):250–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1993.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nader PR, Kaczorowski J, Benioff S, Tonniges T, Schwarz D, Palfrey J. Education for community pediatrics. Clin Pediatr. 2004;43(6):505–521. doi: 10.1177/000992280404300602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shipley LJ, Stelzner SM, Zenni EA, Hargunani D, O'Keefe J, Miller C, et al. Teaching community pediatrics to pediatric residents: strategic approaches and successful models for education in community health and child advocacy. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):1150–1157. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2825J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerrero LR, Baillie S, Wimmers P, Parker N. Educational experiences residents perceive as most helpful for the acquisition of the ACGME competencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):176–183. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00058.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Illing J, Van Zwanenberg T, Cunningham WF, Taylor G, O'Halloran C, Prescott R. Preregistration house officers in general practice: review of evidence. BMJ. 2003;326(7397):1019–1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7397.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz KW, Kirby J, Delva D, Godwin M, Verma S, Birtwhistle R, et al. Medical students' and residents' preferred site characteristics and preceptor behaviours for learning in the ambulatory setting: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson J, Allan B, Anderson K, Kljakovic M. GP interest in teaching junior doctors: does practice location, size and infrastructure matter? Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(12):1000–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stake R. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE;; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy TJ, Lingard LA. Making sense of grounded theory in medical education. Med Educ. 2006;40(2):101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charmaz K. Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;; 2000. pp. 509–535. In. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada: The CanMEDS Framework. 2005 http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/canmeds/framework. Accessed June 11, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada. The Future of Medical Education in Canada Postgraduate Project. 2012 https://www.afmc.ca/future-of-medical-education-in-canada/postgraduate-project/pdf/FMEC_PG_Final-Report_EN.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2015. [Google Scholar]