Abstract

Background

Undergraduate medical education (UME) follows the lead of graduate medical education (GME) in moving to competency-based assessment. The means for and the timing of competency-based assessments in UME are unclear.

Objective

We explored the feasibility of using the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Transitional Year (TY) Milestones to assess student performance during a mandatory, fourth-year capstone course.

Methods

Our single institution, observational study involved 99 medical students who completed the course in the spring of 2014. Students' skills were assessed by self, peer, and faculty assessment for 6 existing course activities using the TY Milestones. Evaluation completion rates and mean scores were calculated.

Results

Students' mean milestone levels ranged between 2.2 and 3.6 (on a 5-level scoring rubric). Level 3 is the performance expected at the completion of a TY. Students performed highest in breaking bad news and developing a quality improvement project, and lowest in developing a learning plan, working in interdisciplinary teams, and stabilizing acutely ill patients. Evaluation completion rates were low for some evaluations, and precluded use of the data for assessing student performance in the capstone course. Students were less likely to complete separate online evaluations. Faculty were less likely to complete evaluations when activities did not include dedicated time for evaluations.

Conclusions

Assessment of student competence on 9 TY Milestones during a capstone course was useful, but achieving acceptable evaluation completion rates was challenging. Modifications are necessary if milestone scores from a capstone are intended to be used as a handoff between UME and GME.

Editor's Note: The online version (47KB, doc) of this article contains an extended Table 1 with footnotes.

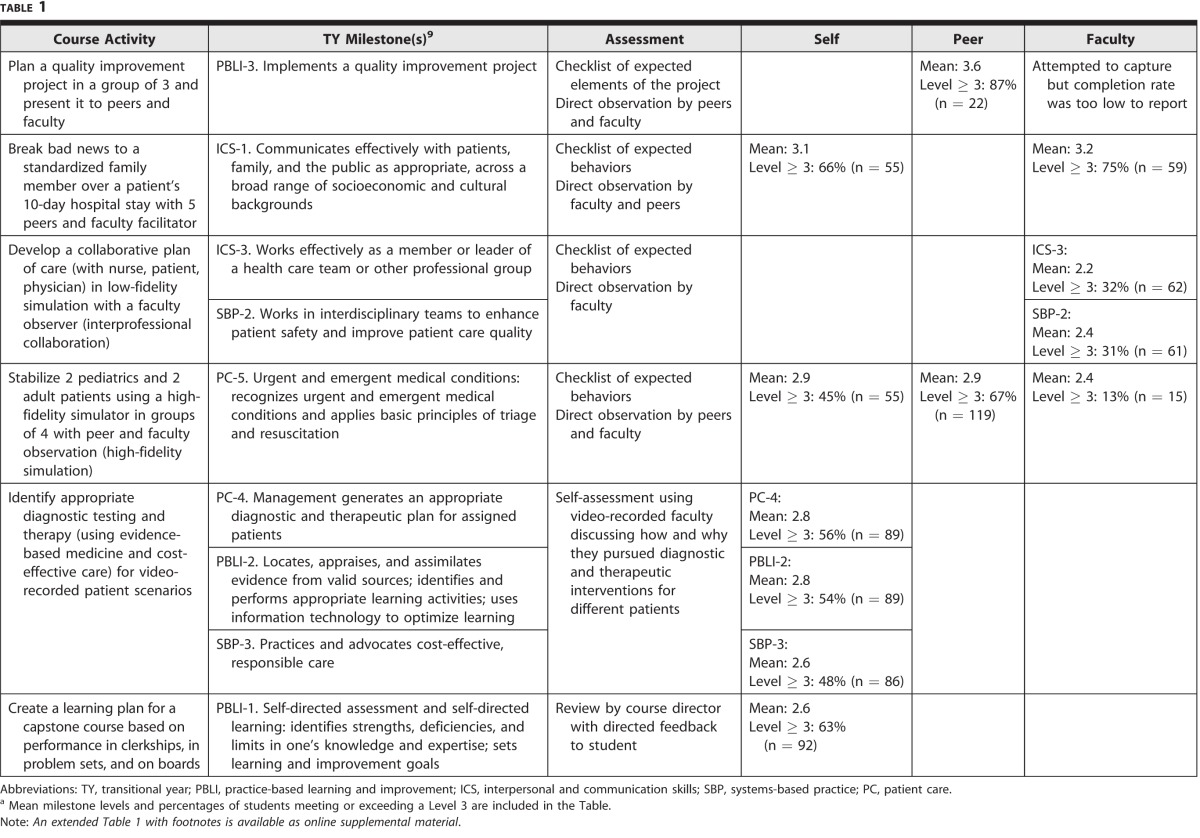

TABLE 1.

Achieved Transitional Year Milestone Level for Students in Capstone 2014a

Introduction

Graduate medical education (GME) in the United States has accelerated its transition to competency-based assessment with the adoption of milestones as part of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) new accreditation system.1 Milestones are narrative descriptors of behaviors that progress from “critical deficiency,” or novice performance, to performance in unsupervised practice. Milestones are based on 6 core competencies: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, systems-based practice, interpersonal and communication skills, and professionalism.1

Undergraduate medical education (UME) also has embraced competency-based education and assessment2 through the adoption of Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency.3 The fourth year of medical school is an ideal time to assess students' performance; while this may add value to an academic year, this added value has been questioned by some.4,5 Using milestones to assess skills during the fourth year offers data on students' skills at the educational handoff from UME to GME.

To date, true baseline performance at matriculation into residency has not been established for graduating medical students.6 Using the milestones to delineate performance standards for graduating medical students would help clarify expectations of teaching and assessment for both faculty and students. Capstone or transition courses may provide an appropriate venue.7,8 In this article, we describe the use of ACGME Transitional Year (TY) Milestones9 to assess student performance in a capstone course.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Participants were 99 Duke University medical students enrolled in the spring of 2014 in a 4-week capstone course required for graduation.

Curriculum

Our capstone course focuses on preparation for internship, including management of on-call issues, personal survival skills, and advanced topics relevant to internship, such as effective teaching and applied evidence-based medicine. The course utilizes a robust assessment strategy employing multirater formative and summative assessments.10

This study was determined to be exempt from review by our Institutional Review Board.

Logistics

TY Milestones were integrated into existing course evaluations to test the feasibility of using milestones in student assessment. TY Milestones were chosen because they are not specialty specific, and they have established performance standards for the end of the internship year. Nine of the 23 TY Milestones were chosen by comparing existing course activities and existing obligatory self, peer, or faculty assessment to specific milestones (table 1). Some activities had a single assessment (self-assessment, faculty by direct observation, or peer by direct observation); others had combinations of the 3 assessments. Students and faculty completed evaluations within 48 hours of sessions using paper evaluations or an online survey tool (Qualtrics).

We reported the mean milestone level achieved by students and the percentage of students who achieved or exceeded a Level 3, as the ACGME expects that GME trainees achieve Level 3 by completion of the transitional year.1

Feasibility data included the number of students who completed each activity, the number of evaluations collected, and the completion rate for milestone assessments.

Results

During the study period, 805 milestone assessments were completed. Mean student performance and completion rates are shown in table 1. Students' mean scores on the 9 milestones ranged from 2.2 to 3.6, including self, peer, and faculty evaluations. More than 50% of students achieved or exceeded Level 3 in breaking bad news and in developing a quality improvement project. Ascertained by faculty observations of student performance during simulation, students performed worse on self-assessment, working in interdisciplinary teams, and managing urgent/emergent conditions.

Low completion rates were a problem for some evaluations, and precluded the use of some of the data in assessing student performance in the capstone course. Student completion rates were lowest for assessments obtained using separate online evaluations, and highest for assessments obtained on paper during the small group exercise or online as part of mandatory assignments. Faculty completed assessments on paper immediately after a session. Faculty completion rates were lower when sessions did not included dedicated time for evaluation, and were lowest for the quality improvement project and simulation and highest for interprofessional collaboration.

Discussion

We assessed student performance for 9 TY Milestones during existing course activities with little additional faculty development, student education, or administrative infrastructure. Both evaluation completion rates and mean student performance varied across the 9 milestones.

While we were able to assess student performance during a 4-week capstone course, this pilot study demonstrated important limitations both with relevance and feasibility. First, we found it challenging to identify the target TY Milestone level for graduating students. Second, we recognized the need to modify our existing course assessments to accurately, consistently, and acceptably measure student competence.

The wide variation in student performance across the milestones raises several questions. Students may enter residency with higher performance on some milestones than others, suggesting a need to target curricular change in areas where students struggle the most (such as interprofessional teamwork) to improve their skills in this area prior to graduation. There may be a benefit in setting varied milestone expectations for student graduation and matriculation into internship. To set the minimum standard for graduation, we need data from multiple institutions.

As a result of the considerable variation in student performance within and across the milestones, we could not easily identify students who might benefit from remediation prior to residency. Redesigning our course model may allow for longitudinal assessment with multiple observations, as the current model of a capstone course only allows a short window prior to graduation, leaving limited time for remediation.

One question that arose is whether medical schools have an obligation to share these data with the GME programs that receive their students. Ideally, sharing these outgoing assessments would facilitate the educational handoff to GME, thus benefiting a student for whom enhanced teaching and supervision would increase the likelihood of success in internship.

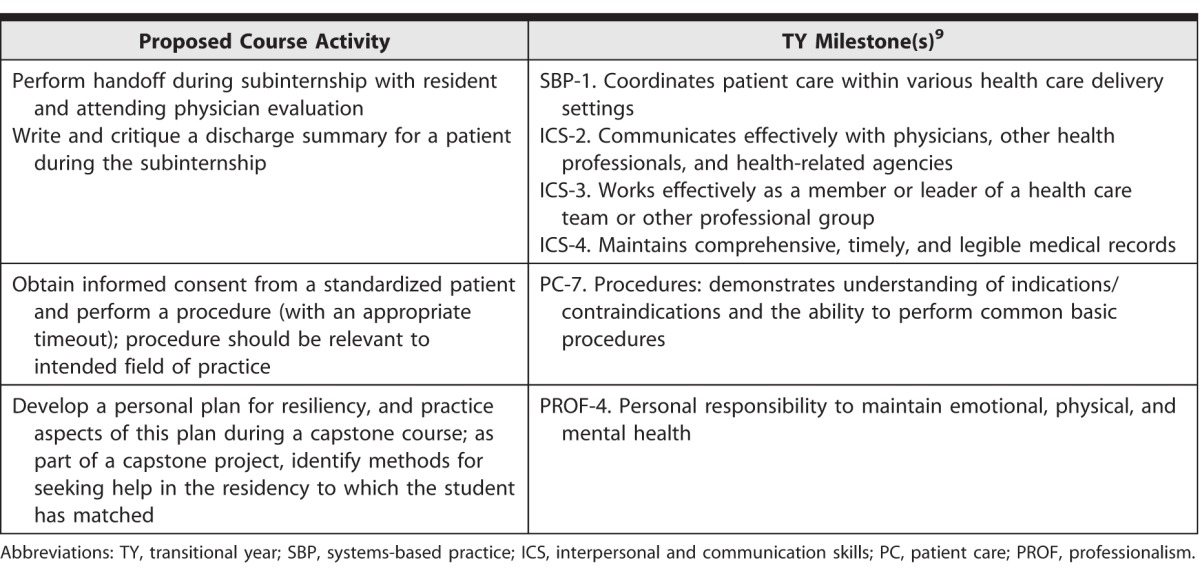

Our study demonstrated that it was difficult to assess 9 milestones over 4 weeks, and this prompted a redesign of our capstone course. We will need a longer course to assess performance on more than 9 milestones. Overlapping the course with subinternship activities will assess student competence during actual patient encounters. In order to achieve a high level of faculty commitment and proficiency with assessment, a small cohort of trained faculty who can commit greater time to the course will be needed. As a result, we will transition our course from a rotational format to a longitudinal format, in which students will complete a set of competency-based skills using the TY Milestones (as described by others for residency),11 and additional TY Milestones will be assessed (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Proposed Course Activities Mapped to Transitional Year Milestones

Ten core faculty members who serve as capstone coaches will receive consistent faculty development on competency assessment, and will be required to commit to timely completion of evaluations. Each faculty member will be assigned a small group of students, allowing timely assessment and feedback to students over the entire fourth year, and each will follow up on student completion of exercises and evaluations, thereby increasing student accountability. We plan to study coaches' inter- and intraobserver reliability.

Conclusion

A competency-based approach to assessment in a fourth-year capstone course using the TY Milestones identified variation in student performance within and across milestones, challenges with evaluation completion rates, and challenges with implementing milestone assessments during this 4-week course when remediation of low-performing students is no longer feasible. Future work is needed to further delineate performance expectations for graduating medical students to facilitate the handoff between medical school and internship.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

All authors are at Duke University School of Medicine. Alison S. Clay, MD, is Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery; Kathryn Andolsek, MD, MPH, is Professor, Community and Family Medicine, and Assistant Dean, Premedical Education; Colleen O'Connor Grochowski, PhD, is Associate Dean, Curricular Affairs; Deborah L. Engle, EdD, MS, is Director of Assessment and Evaluation; and Saumil M. Chudgar, MD, MS, is Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Conflict of interest: the authors declare they have no competing interests.

This study was selected for oral presentation in abstract form, without data, for the Association of American Medical Colleges Medical Education Meeting in Chicago, Illinois, November 6–7, 2014.

The authors would like to thank both Rob Tobin, course administrator, for the capstone course, and Justin Hudgins, staff member in the Office of Curricular Affairs Assessment, for incorporating the milestones into the capstone evaluations, their commitment to the use of technology and innovation, and their patience with teaching faculty and students. The authors would also like to thank Marilyn Oermann, PhD, for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Milestones. 2015 http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/430/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/NextAccreditationSystem/Milestones.aspx. Accessed July 22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Englander R, Cameron T, Ballard AJ, Dodge J, Bull J, Aschenbrener CA. Toward a common taxonomy of competency domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1088–1094. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Englander R, Aschenbrener CA, Call SA, Cleary L, Garrity M, Lindeman B, et al. Core entrustable professional activities for entering residency (updated) 2015 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001204. http://www.mededportal.org/icollaborative/resource/887. Accessed July 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein D. Ensuring an effective physician workforce for the United States: recommendations for reforming graduate medical education to meet the needs of the public. 2015 May 2011. http://macyfoundation.org/docs/macy_pubs/JMF_GME_Conference2_Monograph(2).pdf. Accessed July 22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyss-Lerman P, Teherani A, Aagaard E, Loeser H, Cooke M, Harper GM. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):823–829. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a82426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santen SA, Rademacher N, Heron SL, Khandelwal S, Hauff S, Hopson L. How competent are emergency medicine interns for level 1 milestones: who is responsible? Acad Med. 2013;20(7):736–739. doi: 10.1111/acem.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scicluna HA, Grimm MC, O'Sullivan AJ, Harris P, Pilotto LS, Jones PD, et al. Clinical capabilities of graduates of an outcomes-based integrated medical program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo AR, Harleman E, O'Sullivan PS, Maa J. The key role of a transition course in preparing medical students for internship. Acad Med. 2011;86(7):860–865. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821d6ae2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Transitional year. 2015 http://acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/153/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/Hospital-BasedSpecialties/TransitionalYear.aspx. Accessed July 22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scicluna HA, Grimm MC, Jones PD, Pilotto LS, McNeil HP. Improving the transition from medical school to internship—evaluation of a preparation for internship course. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarris LM, Jones D, Kornegay JG, Hansen M. The milestones passport: a learner- centered application of the milestone framework to prompt real-time feedback in the emergency department. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):555–560. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00409.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.