An overview of the native nephrogenic niche, describing the complex signals that allow survival and maintenance of undifferentiated renal stem/progenitor cells and the stimuli that promote differentiation, is provided.

Keywords: Kidney, Progenitor cells, Stem cell culture, Self-renewal, Differentiation, Embryonic stem cells, Induced pluripotent stem cells, Stem/progenitor cell

Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as progressive kidney damage and a reduction of the glomerular filtration rate, can progress to end-stage renal failure (CKD5), in which kidney function is completely lost. CKD5 requires dialysis or kidney transplantation, which is limited by the shortage of donor organs. The incidence of CKD5 is increasing annually in the Western world, stimulating an urgent need for new therapies to repair injured kidneys. Many efforts are directed toward regenerative medicine, in particular using stem cells to replace nephrons lost during progression to CKD5. In the present review, we provide an overview of the native nephrogenic niche, describing the complex signals that allow survival and maintenance of undifferentiated renal stem/progenitor cells and the stimuli that promote differentiation. Recapitulating in vitro what normally happens in vivo will be beneficial to guide amplification and direct differentiation of stem cells toward functional renal cells for nephron regeneration.

Significance

Kidneys perform a plethora of functions essential for life. When their main effector, the nephron, is irreversibly compromised, the only therapeutic choices available are artificial replacement (dialysis) or renal transplantation. Research focusing on alternative treatments includes the use of stem cells. These are immature cells with the potential to mature into renal cells, which could be used to regenerate the kidney. To achieve this aim, many problems must be overcome, such as where to take these cells from, how to obtain enough cells to deliver to patients, and, finally, how to mature stem cells into the cell types normally present in the kidney. In the present report, these questions are discussed. By knowing the factors directing the proliferation and differentiation of renal stem cells normally present in developing kidney, this knowledge can applied to other types of stem cells in the laboratory and use them in the clinic as therapy for the kidney.

Introduction

A normal kidney comprises millions of different specialized cells cooperating together to perform the roles essential for life; the functions range from the removal of metabolic waste from blood to the maintenance of water, electrolyte, and acid base homeostasis. The kidney also has an important role as an endocrine organ producing hormones that act on the skeleton and circulatory system. On average, each kidney comprises approximately 900,000 to 1 million nephrons, although this number can vary widely, and a low nephron number has been associated with increased risk factors for kidney disease [1, 2]. Nephrons arise in the cortex, loop into the medulla, and then back into the cortex, where they empty into collecting ducts. Urine starts being made in the first part of the nephron, the glomerulus, where a network of capillaries lined by vascular endothelial cells forms a filtration barrier with epithelial podocytes. These are separated by a basement membrane composed of specialized extracellular matrix [3, 4] and supported by mesangial cells. Bowman’s capsule surrounds the glomerulus and guides glomerular filtrate toward the renal tubule, where its chemical composition (e.g., water, electrolytes, glucose) is sequentially modified as it passes through the proximal tubule, loop of Henle, and distal tubule. The latter tubule empties into the collecting duct where specialized cells fine tune the sodium, potassium, water, and pH balance. Collecting ducts drain into the renal pelvis and thence to the ureter and bladder [3]. All these structures are surrounded by the renal interstitium, which contains fibroblasts and vascular and lymphatic components.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as a structural or functional abnormality of the kidney, present for more than 3 months, with repercussions for health [5]. According to kidney function, CKD has five stages, with the fourth and fifth the most severe stages, in which function is severely reduced or lost. CKD affects up to 11% of the adult population in the Western world and is becoming more prominent, with the increasing incidence of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension [6]. Young people can also be affected, with a total of 891 young people younger than 18 years old with severe renal failure registered in the U.K. and awaiting renal transplantation [7]. Patients with CKD5 require dialysis and renal transplantation. Both treatments have important limitations, such as cardiovascular morbidity, mortality, and poor quality of life in the case of dialysis, and kidney transplantation requires well-matched donors and lifelong antirejection therapy for the best outcomes.

Classically, the kidney has been classified as a nonregenerative organ. However, evidence is emerging for its regenerative capacity after injury, although investigators argue over which mechanism contributes to repair. Some studies have suggested that renal epithelial cells respond to local injury by dedifferentiating and proliferating [8], and others have postulated that local progenitor cells might participate in regeneration [9–12]. Whichever mechanism is involved, however, the problem is that this capacity for repair is limited and is lost with progressive CKD.

Regenerative medicine is clearly an appealing strategy for CKD. The first requirement is to identify potential renal stem/progenitor cells (RSPCs) able to either generate fresh new nephrons or repair the damaged ones before they are too severely injured. The term “stem cells” defines a population of clonogenic cells possessing unlimited self-renewal and capability to differentiate toward multiple lineages. The term “progenitor cells” defines a cell population that is more restricted in differentiation potential and has limited self-renewal capacity [13]. In the present review, we confine the term “stem cells” to embryonic stem cells (ESCs) derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst—these are able to generate all three embryonic germ layers. In contrast, induced pluripotent stem cells are denoted iPSCs; these are pluripotent stem cells usually generated by ex vivo reprogramming of somatic cells. RSPCs indicate both human and murine cells derived from embryonic and adult kidneys with both “stem”-like features, such as multipotency and “progenitor” characteristics, such as a limited capacity for self-renewal, depending on the source from which they are isolated. RSPCs are found in the normal developing kidney, which one would predict to have the widest range of developmental fates, but also in the adult kidney, albeit with a more restricted differentiation potential [13]. We describe how RSPC maintenance and differentiation is controlled during nephrogenesis to suggest strategies that mimic this normal milieu in vitro.

Kidney Development and RSPCs

The mature mammalian kidney is the final product of three embryonic stages: two transitory structures, the pronephros and mesonephros, and the metanephros, which develops into the adult kidney [14]. In humans, new nephron formation, or nephrogenesis, starts during the 5th week of gestation, the first glomeruli appear at the 9th week, and the last new nephron is formed by the 36th week of gestation. In mice, nephrogenesis starts at embryonic day 10.5, with the first glomeruli at embryonic day 14 and the last new nephron approximately 1 week to 10 days after birth [15].

The metanephros forms from the caudal part of the intermediate mesoderm, which characteristically expresses key specification markers, including the lim-type homeobox gene (Lhx1), odd-skipped related gene (Osr1), and paired-box genes 2 and 8 (Pax2, Pax8) [16]. The metanephros develops when an outgrowth from the caudal portion of the nephric duct migrates toward and then invades the metanephric mesenchyme; this epithelial outgrowth is called the ureteric bud. A key signaling system in the outgrowth process is the ligand glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) produced by the mesenchyme and acting on the RET receptor tyrosine kinase in the nephric duct and burgeoning bud [17]. Important roles are also attributed to the homeobox gene family (Hox) in the intermediate mesoderm, in particular, Hox11 paralogs (Hoxa11, Hoxc11, and Hoxd11), also important in induced pluripotent cells [18]. Together, these are necessary for the expression of markers delineating the metanephric mesenchyme, such as GDNF and sine oculis-related homeobox 2 (Six2), one of the master regulators of nephrogenesis [19].

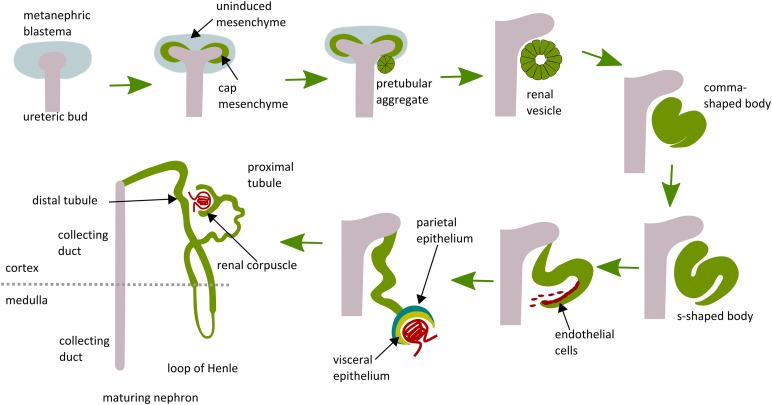

The ureteric bud provides signals that cause mesenchymal cells adjacent to bud tips to form a tightly packed cap, termed “cap mesenchyme.” This mesenchyme releases factors, such as GDNF and hepatocyte growth factor, that induce repeated branching of the ureteric bud to generate the urinary system, comprising collecting ducts, renal pelvis, and ureter. The ureteric bud secretes different factors, including Wnt proteins, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), that promote survival and differentiation of the cap mesenchyme. As the ureteric bud branches, the cap mesenchyme is induced to become epithelium through the key process of mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET) [20]. The first structure to appear is the renal vesicle, which elongates to form a comma-shaped body and then an S-shaped body (Fig. 1). The distal end of the S-shaped body fuses with the ureteric bud tip and gives rise to the distal tubule. The middle part becomes the loop of Henle and proximal tubule, and the proximal end farthest from the ureteric bud tips is organized in two epithelial layers, the parietal and visceral epithelium, which will, respectively, form Bowman’s capsule and the podocytes (Fig. 1) [17, 21]. At this end, the S-shaped body forms a vascular cleft in which endothelial cells and mesangial migrate to form the glomerular capillaries (Fig. 1) [21]. The cap mesenchyme is surrounded by loosely arranged stromal cells. A subset of these cells express the transcription factor winged-fork head transcription factor 1 (Foxd1), which gives rise to glomerular mesangial cells, fibroblasts, pericytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and renin-secreting cells. Another subset of cells characterized by the expression of tyrosine-protein kinase kit contributes to endothelial cells, with some debate regarding whether these develop in situ or via ingrowth [22–25].

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of stages of nephron development. The ureteric bud grows out from the nephric duct and invades the surrounding metanephric mesenchyme, initiating nephron development. Subsets of mesenchymal cells in the metanephric blastema are induced to condense around the ureteric bud tips. This population is the potential source of renal stem/progenitor cells termed “cap mesenchyme.” Cap mesenchyme forms pretubular aggregates, then epithelializes to renal vesicles, which elongate to comma- and S-shaped bodies. These connect to the ureteric bud stalk, which gives rise to the collecting duct. The S-shaped bodies differentiate into distal tubules, proximal tubule, loop of Henle, glomerular Bowman’s capsule (derived from parietal epithelium), and podocytes (derived from visceral epithelium).

Which of These Cells Might Be Useful for Nephron Replacement?

Based on its development in vivo, the cap mesenchyme is the most obvious source of RSPCs. Cap mesenchyme cells are characterized by several transcription factors, including Osr1, Pax2, Wt1, Six2, and Cpb/300-interacting transactivator 1(Cited1).

Osr1 has an earlier role in generic specification of the mesoderm toward intermediate mesoderm; however, here it is expressed in the cap mesenchyme and maintains the RSPC pool in conjunction with Six2 [26]. Osr1 is downregulated on MET [27, 28], and transgenic inactivation in the cap mesenchyme causes premature differentiation [26, 29].

Pax2 encodes a transcription factor critical for normal nephrogenesis [30]. It is expressed in the intermediate mesoderm, and then in the actively branching tips of the ureteric buds and the cap mesenchyme, where it is essential for MET [31, 32], alongside the Wilms tumor gene, WT1 [33].

Six2 expression is absolutely critical for maintenance and differentiation of cap mesenchyme. Higher Six2 levels promote continual self-renewal of RSPCs. Then, as expression decreases, the cells undergo MET, it is absent in adult kidneys [34–36]. Experimental loss of Six2 during development forces the cells out of the continual renewal phase and causes premature epithelialization, with depletion of cap mesenchyme cells leading to small kidneys with fewer nephrons [37].

Cited1 is coexpressed in the cap mesenchyme within a subset of Six2-positive (Six2+). It is downregulated before MET and is absent in the adult kidney. Surprisingly, its loss does not impair kidney development, suggesting the presence of potential compensatory mechanisms [36, 38].

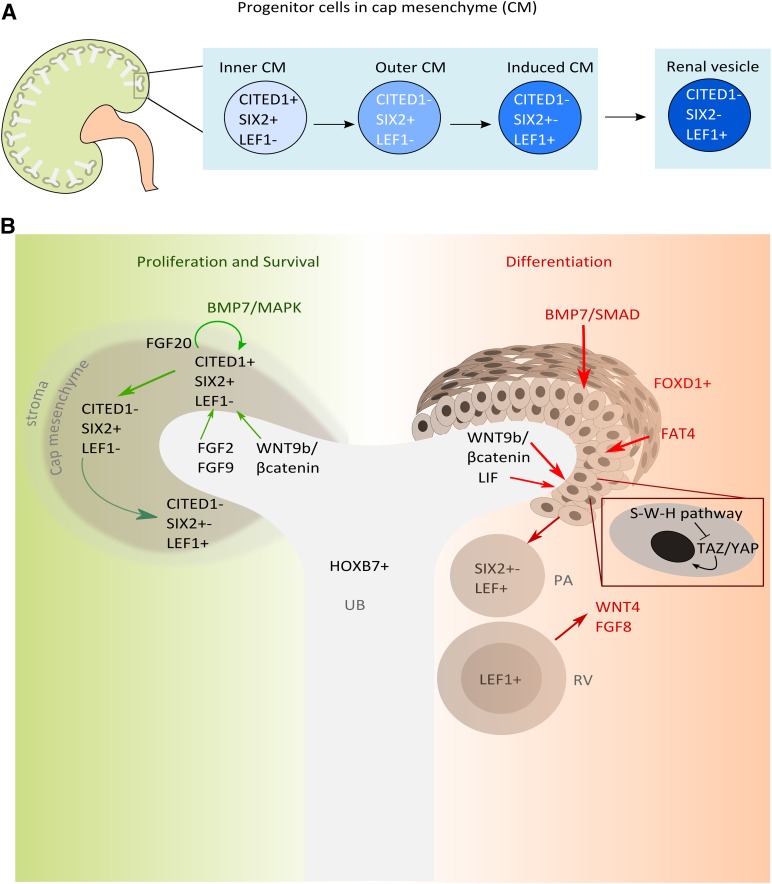

RSPC Progression

Stem cells have a low turnover rate in normal adult tissues; injury stimulates subsets of cells into action but others remain quiescent [39]. This duality prevents premature exhaustion of stem cell pools, thus providing a long-term regenerative resource for the tissue. RSPCs within cap mesenchyme might reiterate this. The results from high-resolution mapping suggest that cap mesenchyme is a heterogenic population with subsets of cells differentially expressing transcriptional regulators [40–42]. The earliest RSPCs, in the inner part of the cap mesenchyme, are molecularly characterized by CITED1 and SIX2 localization (Fig. 2A) [40]. This population possesses the greatest capacity for self-renewal and differentiation and is refractory to differentiating signals, such as WNT9b secreted from the ureteric bud [41]. Cells in the next phase of differentiation, in the outer part of the cap mesenchyme, maintain Six2 expression but downregulate Cited1 and acquire the potential to respond to WNT signaling. Next, the cells downregulate Six2 and activate WNT differentiation gene targets via β-catenin interaction of T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (Lef1) (Fig. 2A) [36, 40, 41, 43].

Figure 2.

Renal stem/progenitor cell (RSPC) compartments in the nephrogenic niche and the signals promoting survival, proliferation, and differentiation. (A): The outer cortex of the developing kidney is the site of nephrogenesis. Here, the ureteric bud branches many times, inducing new nephrons with each tip. RSPCs, in the induced cap mesenchyme, progress through different stages, each with a distinct molecular signature. Early undifferentiated RSPCs express the transcription factors Cited1 and sine oculis-related h omeobox 2 (Six2); further differentiation is characterized by the downregulation of first Cited1 and then Six2, with concomitant upregulation of Lef1. LEF1 cells form pretubular aggregates, which then undergo mesenchymal to epithelial transition to form renal vesicles. (B): The nephrogenic niche provides signals promoting survival and differentiation. FGF2, FGF9, FGF20, and BMP7 act synergistically via MAPK and WNT9b/β-catenin to promote the survival and proliferation of the mesenchyme. The ureteric bud, expressing BMP7 via SMAD, LIF, WNT9b/β-catenin, and stromal cells (FOXD1+), releases factors such as FAT4, which induce epithelial differentiation of cap mesenchymal cells. FAT4 acts with WNT9b to enhance the inactivation of YAP/TAZ and further transcription of WNT9b/β-catenin differentiation target genes. Abbreviations: BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CITED1, Cpb/300-interacting transactivator 1; FAT4, FAT atypical cadherin 4; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FOXD1, winged-fork head transcription factor 1; HOXB7, homeobox B7; LEF1, lymphoid enhancer factor 1; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PA, pretubular aggregates; RV, renal vesicle; SIX2, sine oculis-related homeobox 2; S-W-H, Salvador-Warts-Hippo; TAZ/YAP, transcriptional coactivator with PDZ binding motif/Yes associated protein; UB, ureteric bud; WNT, wingless-type MMTV integration site family.

Growth Factors Needed for RSPC Maintenance and Proliferation

Cap mesenchyme is present for 8–10 days during murine development in vivo, and isolated cap mesenchymal cells undergo apoptosis in 48 hours in vitro [44]. The survival of this population and transition from one compartment to the other is reliant on several growth factors. Understanding these factors will help us design culture conditions to mimic this physiological process [45].

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family proteins are important nephrogenic survival molecules. The FGF receptors (FGFRs) include several different receptor tyrosine kinases: FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3 have two variants, “b” and “c,” generated via alternative splicing. These isoforms have a distinctive tissue location, with the b splice variant predominantly in epithelial cell types and the c splice variant in mesenchymal tissues [46]. Inactivation of FGF receptors 1 and 2 in the cap mesenchyme causes aberrant kidney development, suggesting an essential role for FGF signaling [47, 48]. Ligand binding to FGF receptors is facilitated by interaction with the proteoglycan heparin and heparin sulfate. Consequently, in vitro treatment with FGF might require additional heparin-like molecules to optimize binding activity [49]. Several FGFs are expressed in the nephrogenic zone and have multiple roles in maintaining RSPCs [42].

FGF2, secreted from the ureteric bud, prevents apoptosis in isolated, cultured nephrogenic mesenchyme and supports RSPC self-renewal and the capacity to differentiate toward an epithelial fate in response to tubulogenic signals [42, 44, 50, 51]. Surprisingly, however, Fgf2 null mutant mice have relatively normal kidneys, suggesting the presence of possible compensatory mechanisms in vivo [52, 53].

FGF1, FGF9, and FGF20 also have possible roles as survival signals for double CITED1, SIX2-positive early RSPCs, because they are able to maintain this population in culture [42, 54]. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α) can also mimic these roles [42]. The absence of both FGF9 and FGF20 in mice and FGF20 in humans causes impaired kidney development, including renal agenesis [54].

Fgf8 is expressed during nephrogenesis in renal vesicles and renal epithelia [55, 56]. Although Fgf8 mutation in vivo affects the survival of RSPCs, suggesting a role for their maintenance [56], in vitro FGF8 is not able to maintain this population, possibly because it binds with a decoy receptor FGFR1 (expressed in cap mesenchyme) [42].

FGF7 and FGF10 localize in the cap mesenchymal cells and regulate ureteric bud branching by signaling through the FGFR2b [57].

In addition to FGFs, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) have central roles in nephrogenesis. BMPs belong to the transforming growth factor family and bind to cell surface receptor serine/threonine kinases, activating the SMAD (R-SMAD) or mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway [58]. BMP7, in particular, is required in the metanephric mesenchyme to promote survival of RSPCs [50]. Culture of metanephric mesenchyme with BMP7 for up to 96 hours results in its survival but not further tubular differentiation [50]. Loss of BMP7 in vivo leads to a premature stop in nephrogenesis owing to increased cortical apoptosis and decreased cell self-renewal [59]. BMP7 also promotes PAX2-positive RSPC proliferation through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, demonstrating a role, not only in cell survival, but also in cell division [60]. BMP7 influences RSPC progression through cap mesenchyme stages; BMP7-induced SMAD signaling supports the transition from the earliest RSPC compartment to a more committed status characterized by the downregulation of Cited1 and upregulation of Six2, at which point the cells become susceptible to ureteric bud-generated WNT signals (Fig. 2A) [41].

Signaling Factors Needed for RSPC Differentiation

Ureteric Bud-Derived Factors

Several factors secreted by the ureteric bud are implicated in the epithelialization of cap mesenchyme, including WNTs [61, 62], LIF [63, 64], and TGF-2 [64].

WNT9b and WNT4 play central roles in the regulation of MET in vivo. Spinal cord-derived WNT1 can also induce MET in heterologous culture, although this Wnt is not normally found in the developing kidney [65]. Murine embryos lacking Wnt9b have major defects in ureteric bud branching such that kidneys do not form, and Wnt4 null mutants exhibit hypoplastic kidneys with undifferentiated mesenchyme and fewer mature epithelial structures [20, 66]. In addition, mutation of human WNT4 causes renal dysgenesis, suggesting clinical relevance for this molecule [67, 68]. WNT/β-catenin signaling to RSPCs can control either self-renewal or differentiation. WNT9b/β-catenin can maintain the undifferentiated state through activation of progenitor target genes such as Cited1 [69]. These roles appear to be mediated by cooperation with SIX2, although the exact mechanism is still unknown [69, 70]. WNT9b/β-catenin can also induce expression of Fgf8, Pax8, and Wnt4 triggering differentiation in RSPCs [20, 55, 71].

Other molecules cooperate with Wnt signaling, such as the LIF, an interleukin-6 class cytokine specifically expressed by the ureteric bud. LIF stimulation in vitro starts epithelial differentiation of isolated rat metanephric mesenchyme, which can subsequently develop tubules and glomeruli [63]. Also, LIF-induced epithelial differentiation is greatly enhanced by the addition in vitro of transforming growth factors and FGF2, although the addition in cell cultures of these factors alone does not facilitate full epithelial differentiation [51, 72]. These factors when tested on isolated mouse mesenchyme did not show the same effects, possibly owing to species variances or culture requirements [42, 63].

Experiments performed by our group using human RSPCs isolated from the first trimester of gestation showed that these cells express cap mesenchymal genes, such as PAX2, SIX2, CITED1, and GDNF and maintain a mesenchymal phenotype over many passages [73]. When cultured with LIF, TGF-α, and FGF2, they showed changes in morphology suggesting a more aligned pattern of growth but did not display significant expression of epithelial genes [74].

Chemical Compounds

Lithium ions and 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (BIO) inhibit glycogen synthase kinase 3β in the WNT pathway, hence increasing β-catenin levels, mimicking canonical signaling; this promotes epithelial differentiation in metanephric mesenchyme [75]. Early markers of epithelial transition in RSPCs are stimulated by continuous activation of WNT signaling in vivo via expression of the dominant active form of β-catenin or in vitro via BIO treatment over 48 hours [70, 71]. Monolayer culture of RSPCs stimulated transiently with BIO did not achieve epithelial differentiation, unlike when cultured in an aggregated pellet, suggesting that cell interactions in three dimensions might be a key factor.

Stromal-Derived Factors

Cap mesenchyme cells are surrounded by stroma in the developing kidney, a population of loose mesenchyme that eventually generates interstitial cells, the mesangium, and the vascular cells of the mature kidney [23]. Ablation of Foxd1, which is expressed in the stroma, has a severe effect on nephrogenesis, with disruption of the ureteric tree and mislocalization of prenephrogenic structures, such as pretubular aggregates and renal vesicles, leading to a marked reduction in nephron numbers [76, 77]. Observation that the ureteric bud factor WNT9b promotes either differentiation or self-renewal of RSPC cells led to the hypothesis that other signals might cooperate with the ones secreted from the ureteric bud to determine the balance between differentiation and self-renewal. A pathway involved in maintaining this balance is the Salvador-Warts-Hippo. This signaling pathway has relevant influence in kidney development, because deletion of one of its effectors, the Yes-associated protein (YAP), specifically in the cap mesenchyme, results in impaired kidney development, with hypoplastic kidneys showing a few abnormal glomeruli and few renal tubules [78]. For instance, stromal cells express modulates RSPC differentiation in the presence of ureteric bud WNT9b via the expression of FAT4, an atypical cadherin in this pathway [79]. FAT4 induces RSPC differentiation by the dual effects of inhibiting self-renewal genes such as Cited1 and promoting WNT9b/β-catenin differentiation factors such as Pax8 and Wnt4. The combination of WNT9b (from the ureteric bud) and FAT4 (from the stroma) inactivates YAP and the transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif, allowing the transcription of WNT9b/β-catenin differentiation target genes. In contrast, YAP is active when FAT4 is absent and localizes to the nucleus, where it drives the transcription of β-catenin pro-self-renewal target genes (Fig. 2B) [79].

RSPCs in Adult Kidney

On completion of nephrogenesis, the cap mesenchyme is exhausted, and new nephrons will not form. This would suggest that the RSPCs present during development are lost in the adult. However, several groups have shown evidence for the existence of adult RSPCs in human kidneys. Adult RSPCs were isolated from total kidneys [12, 80], renal cortex [81], renal corpuscle [82], nephron tubules [83], and renal inner medulla [84]. Strategies for the identification and isolation relied on the expression of stem cell surface markers [80–84] or stem cells features, such as self-renewal [12]. Regardless of the isolation strategy used, the cells exhibited self-renewal capacity, the ability to differentiate toward renal tubules and podocytes and different lineages. RSPCs were further molecularly characterized and showed expression of the embryonic transcription factor OCT4 [82] and renal developmental genes PAX2 [12, 81], SIX2, SALL1, and WT1 [80] and reduced expression of fully differentiated kidney cells markers [80, 82]. RSPCs were also found in the adult kidneys of rodents, showing long-term self-renewal and Pax2 expression [85]. Other studies have shown that potential RSPCs are not present in adult human kidneys. On injury, renal cells might lose differentiation and participate in regeneration, acquiring different characteristics that could be mistaken for progenitor cell-like traits [34, 86]. Moreover, recent fate-tracing experiments in mice further demonstrated that fully differentiated epithelial cells, rather than progenitor cells, contribute to repair after injury [87].

Generation of RSPCs From Embryonic and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

Renal stem cells represent a potentially enticing strategy for renal repair and regeneration, but their clinical use is still a long way off. One issue is the best source of these cells, and a recent approach has used pluripotent stem cells that can be differentiated toward renal lineages.

Pluripotent stem cells possess the capacity for unlimited self-renewal and the ability to differentiate into the three germ layers of the embryo. Pluripotent stem cells have two main types: ESCs, isolated from the inner cell mass of the embryo, and iPSCs generated by reprogramming differentiated somatic cells to an embryonic stem cell-like state [88–90].

These represent an ideal source of multipotent stem cells for use in kidney regeneration. The challenge would be to differentiate pluripotent stem cells to generate nephron progenitors able to reconstitute the whole nephron structure.

Differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells toward a renal lineage has been induced by treatment of embryonic stem cells aggregates (embryonic bodies) with activing A, retinoic acid, and BMP7 [91]. The first two have previously been shown to induce the expression of intermediate mesoderm marker Lhx1 in Xenopus [92], and BMP7 is, as already discussed, essential for metanephric mesenchyme survival. On the addition of these factors to embryoid bodies, expression of intermediate mesoderm markers such as Pax2 and Wt1 increases, and on stimulation of metanephric mesenchyme with embryonic spinal cord, expression of renal epithelial makers was observed, suggesting that these factors can promote nephron differentiation [91]. Other groups have reported similar approaches for differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells, also confirming their capacity to undergo tubulogenesis and form glomeruli when grafted in vivo [93–96].

Takasato et al. [97] adapted and improved the embryonic stem cell differentiation protocol on human stem cells by adding FGF9. This was a multistep process. The differentiation steps included initial induction of the primitive streak, the progenitor of endoderm and mesoderm, using opposing gradients of BMP4 and activin A. The primitive streak was then induced toward intermediate mesoderm by adding FGF9, with differentiation efficiency assessed by the expression of intermediate mesoderm markers, including PAX2, OSR1, and LHX1. In turn, the intermediate mesoderm was shifted toward the metanephros by FGF9, BMP7, and retinoic acid. This generates expression of typical metanephric genes such as SIX2, WT1, GDNF, HOXD11, C-RET, and HOXB7. Further differentiation toward renal lineages, such as podocytes, proximal tubule cells, and collecting ducts, was also observed using lineage-specific marker expression. Importantly, differentiated cells obtained from human ESCs using this protocol were able to self-organize and generate nephron-like structures in vitro. This elegant, several-stage process shows that stem cell differentiation toward multiple renal lineages is possible with a good understanding of the factors involved in embryogenesis and replicating them in vitro. However, the potential of these cells to supplement renal function in vivo remains to be assessed.

Recently, lineage-tracing experiments in mice have revealed that ureteric bud and metanephric mesenchyme do not share a common precursor, as previously assumed, but arise from distinct ones. In particular, precursors of metanephric mesenchyme localize to posterior mesoderm that expresses Brachyury (T), and ureteric bud precursors localizes to T-negative anterior mesoderm in the postgastrulation stage embryo. Based on this knowledge, a protocol was reported to specifically differentiate embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells toward posterior metanephric progenitors. The investigators achieved this differentiation through four main steps: (a) formation of mesoderm; (b) formation and maintenance of posterior T+ precursors with a high concentration of WNT agonist; (c) induction of kidney lineage-specific Osr1-, Wt1-, and Hox1-expressing cells by decreasing WNT agonist concentration and adding retinoic acid; and, finally, (d) formation of metanephric mesenchyme expressing Osr1, Wt1, Pax2, Six2, Gdnf, and Hox11 by a further decrease of WNT and the addition of FGF9. These RSPCs were shown to be able to undergo tubulogenesis and form vascularized glomeruli when grafted in vivo beneath the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice, together with spinal cords.

iPSCs are another source of pluripotent stem cells. These are obtained by inducing expression of the Yamanaka factors OCT4, SOX2, c-MYC, and KLF4 in somatic cells, causing reversion toward an embryonic state [89]. These cells should have the same potential to differentiate toward any cell lineage as embryonic stem cells. Their use also overcomes the ethical issues raised by the use of embryonic stem cells and compatibility issues because they come from the patient. Manipulating iPSCs to regenerate the same tissue as their origin theoretically offers even greater advantages, because they often maintain the epigenetic signature characteristic of that tissue [98]. For this reason, iPSCs have been obtained from differentiated kidney cells such as adult human proximal tubule cells [99] and from urine [100]. Different reprogramming factors can also work in this case. Hendry et al. [18] generated RSPCs from adult human proximal tubule cell lines (HK2) by overexpressing SIX1, SIX2, OSR1, HOXA11, EYA1, and SNAI2 using lentiviruses. These induced upregulation of cap mesenchyme-specific markers such as CITED1 and downregulation of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin. Moreover, the cells appeared to contribute to the cap mesenchyme in the reconstitution organoid assay [101, 102].

An obvious problem with generating iPSCs is the necessity of using lenti- or retrovirus vectors to transfect the cells with each gene of interest. Unwanted effects can include nonspecific integration with potential oncogenic consequences. Studies to overcome these drawbacks have focused on the use of alternative nonintegration methods; however, thus far, these have shown very low reprogramming efficiency [103, 104].

RSPC Applications in Regenerative Medicine of the Kidney

Recent progress has encouraged the establishment of a defined culture protocol to direct differentiation of pluripotent stem cells toward specialized renal cell types. This would be a powerful source for cell replacement therapies. However, many issues remain to be solved to achieve this goal. The limitations so far include a low yield of efficient differentiation toward renal lineages and a lack of an effective test of differentiated cell function. Although these cell-based approaches would be very useful in the first stages of CKD, the whole organ replacement would be required in the later stages of CKD. In such cases, repopulation of a decellularized kidney with KSPCs might be a promising method of renal replacement. Recently, the generation of a functional kidney by decellularization and recellularization of a rat kidney using both human endothelial cells to create the vasculature and embryonic rat kidney progenitor cells to form the tubules and glomeruli has been reported [105].

Conclusion

The number of humans with kidney disease is increasing every year in the Western world, and an efficient alternative to kidney transplantation is needed. Stem cell approaches are promising; however, to make them clinically feasible, a better understanding of the molecular controls of normal nephrogenesis and additional analysis of the best cell types to use are needed.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those authors whose work was not included because of length constraints. This work was supported by European Union through the International Training Network (ITN) Project Nephrotools. C.M. is an early stage researcher within Nephrotools Network. We thank Sara Benedetti, Jennifer Huang, and Karen Price for reading the manuscript and making valuable comments.

Author Contributions

C.M. and P.W.: manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bertram JF, Douglas-Denton RN, Diouf B, et al. Human nephron number: Implications for health and disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1529–1533. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puelles VG, Hoy WE, Hughson MD, et al. Glomerular number and size variability and risk for kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:7–15. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283410a7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams J, Phillips A. Structure and function of the kidney. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miner JH. The glomerular basement membrane. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inker LA, Astor BC, Fox CH, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:713–735. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szczech LA, Lazar IL. Projecting the United States ESRD population: Issues regarding treatment of patients with ESRD. Kidney Int Suppl. 2004;90:S3–S7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pruthi R, Hamilton AJ, O’Brien C, et al. UK Renal Registry 17th annual report: Chapter 4—Demography of the UK paediatric renal replacement therapy population in 2013. Nephron. 2015;129(suppl 1):87–98. doi: 10.1159/000370274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphreys BD, Czerniak S, DiRocco DP, et al. Repair of injured proximal tubule does not involve specialized progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9226–9231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100629108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angelotti ML, Ronconi E, Ballerini L, et al. Characterization of renal progenitors committed toward tubular lineage and their regenerative potential in renal tubular injury. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1714–1725. doi: 10.1002/stem.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poulsom R, Little MH. Parietal epithelial cells regenerate podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:231–233. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loverre A, Capobianco C, Ditonno P, et al. Increase of proliferating renal progenitor cells in acute tubular necrosis underlying delayed graft function. Transplantation. 2008;85:1112–1119. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816a8891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bombelli S, Zipeto MA, Torsello B, et al. PKH(high) cells within clonal human nephrospheres provide a purified adult renal stem cell population. Stem Cell Res (Amst) 2013;11:1163–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rookmaaker MB, Verhaar MC, van Zonneveld AJ, et al. Progenitor cells in the kidney: Biology and therapeutic perspectives. Kidney Int. 2004;66:518–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Rahilly R, Muecke EC. The timing and sequence of events in the development of the human urinary system during the embryonic period proper. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1972;138:99–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00519927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reidy KJ, Rosenblum ND. Cell and molecular biology of kidney development. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel SR, Dressler GR. The genetics and epigenetics of kidney development. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33:314–326. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costantini F, Kopan R. Patterning a complex organ: Branching morphogenesis and nephron segmentation in kidney development. Dev Cell. 2010;18:698–712. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendry CE, Vanslambrouck JM, Ineson J, et al. Direct transcriptional reprogramming of adult cells to embryonic nephron progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1424–1434. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mugford JW, Sipilä P, Kobayashi A, et al. Hoxd11 specifies a program of metanephric kidney development within the intermediate mesoderm of the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2008;319:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, et al. Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev Cell. 2005;9:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sequeira-Lopez ML, Lin EE, Li M, et al. The earliest metanephric arteriolar progenitors and their role in kidney vascular development. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:R138–R149. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00428.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaughan MR, Quaggin SE. How do mesangial and endothelial cells form the glomerular tuft? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:24–33. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eremina V, Baelde HJ, Quaggin SE. Role of the VEGF—A signaling pathway in the glomerulus: evidence for crosstalk between components of the glomerular filtration barrier. Nephron Physiol. 2007;106: p32– p37. doi: 10.1159/000101798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt-Ott KM, Chen X, Paragas N, et al. c-Kit delineates a distinct domain of progenitors in the developing kidney. Dev Biol. 2006;299:238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loughna S, Hardman P, Landels E, et al. A molecular and genetic analysis of renal glomerular capillary development. Angiogenesis. 1997;1:84–101. doi: 10.1023/A:1018357116559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Liu H, Park JS, et al. Osr1 acts downstream of and interacts synergistically with Six2 to maintain nephron progenitor cells during kidney organogenesis. Development. 2014;141:1442–1452. doi: 10.1242/dev.103283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.So PL, Danielian PS. Cloning and expression analysis of a mouse gene related to Drosophila odd-skipped. Mech Dev. 1999;84:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lan Y, Kingsley PD, Cho ES, et al. Osr2, a new mouse gene related to Drosophila odd-skipped, exhibits dynamic expression patterns during craniofacial, limb, and kidney development. Mech Dev. 2001;107:175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mugford JW, Sipilä P, McMahon JA, et al. Osr1 expression demarcates a multi-potent population of intermediate mesoderm that undergoes progressive restriction to an Osr1-dependent nephron progenitor compartment within the mammalian kidney. Dev Biol. 2008;324:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dressler GR. Patterning and early cell lineage decisions in the developing kidney: The role of Pax genes. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1387–1394. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1749-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dressler GR. The cellular basis of kidney development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:509–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winyard PJ, Risdon RA, Sams VR, et al. The PAX2 transcription factor is expressed in cystic and hyperproliferative dysplastic epithelia in human kidney malformations. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:451–459. doi: 10.1172/JCI118811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kreidberg JA. WT1 and kidney progenitor cells. Organogenesis. 2010;6:61–70. doi: 10.4161/org.6.2.11928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humphreys BD, Valerius MT, Kobayashi A, et al. Intrinsic epithelial cells repair the kidney after injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi A, Valerius MT, Mugford JW, et al. Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyle S, Misfeldt A, Chandler KJ, et al. Fate mapping using Cited1-CreERT2 mice demonstrates that the cap mesenchyme contains self-renewing progenitor cells and gives rise exclusively to nephronic epithelia. Dev Biol. 2008;313:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Self M, Lagutin OV, Bowling B, et al. Six2 is required for suppression of nephrogenesis and progenitor renewal in the developing kidney. EMBO J. 2006;25:5214–5228. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyle S, Shioda T, Perantoni AO, et al. Cited1 and Cited2 are differentially expressed in the developing kidney but are not required for nephrogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2321–2330. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greco V, Guo S. Compartmentalized organization: A common and required feature of stem cell niches? Development. 2010;137:1586–1594. doi: 10.1242/dev.041103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mugford JW, Yu J, Kobayashi A, et al. High-resolution gene expression analysis of the developing mouse kidney defines novel cellular compartments within the nephron progenitor population. Dev Biol. 2009;333:312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown AC, Muthukrishnan SD, Guay JA, et al. Role for compartmentalization in nephron progenitor differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4640–4645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213971110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown AC, Adams D, de Caestecker M, et al. FGF/EGF signaling regulates the renewal of early nephron progenitors during embryonic development. Development. 2011;138:5099–5112. doi: 10.1242/dev.065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt-Ott KM, Barasch J. WNT/beta-catenin signaling in nephron progenitors and their epithelial progeny. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1004–1008. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perantoni AO, Dove LF, Karavanova I. Basic fibroblast growth factor can mediate the early inductive events in renal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4696–4700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koseki C, Herzlinger D, al-Awqati Q. Apoptosis in metanephric development. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1327–1333. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Itoh N. The FGF families in humans, mice, and zebrafish: Their evolutional processes and roles in development, metabolism, and disease. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1819–1825. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poladia DP, Kish K, Kutay B, et al. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in the metanephric mesenchyme. Dev Biol. 2006;291:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sims-Lucas S, Cusack B, Baust J, et al. Fgfr1 and the IIIc isoform of Fgfr2 play critical roles in the metanephric mesenchyme mediating early inductive events in kidney development. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:240–249. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yayon A, Klagsbrun M, Esko JD, et al. Cell surface, heparin-like molecules are required for binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to its high affinity receptor. Cell. 1991;64:841–848. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90512-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dudley AT, Godin RE, Robertson EJ. Interaction between FGF and BMP signaling pathways regulates development of metanephric mesenchyme. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1601–1613. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barasch J, Qiao J, McWilliams G, et al. Ureteric bud cells secrete multiple factors, including bFGF, which rescue renal progenitors from apoptosis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F757–F767. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.5.F757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ortega S, Ittmann M, Tsang SH, et al. Neuronal defects and delayed wound healing in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5672–5677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dono R, Texido G, Dussel R, et al. Impaired cerebral cortex development and blood pressure regulation in FGF-2-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1998;17:4213–4225. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barak H, Huh SH, Chen S, et al. FGF9 and FGF20 maintain the stemness of nephron progenitors in mice and man. Dev Cell. 2012;22:1191–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grieshammer U, Cebrián C, Ilagan R, et al. FGF8 is required for cell survival at distinct stages of nephrogenesis and for regulation of gene expression in nascent nephrons. Development. 2005;132:3847–3857. doi: 10.1242/dev.01944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perantoni AO, Timofeeva O, Naillat F, et al. Inactivation of FGF8 in early mesoderm reveals an essential role in kidney development. Development. 2005;132:3859–3871. doi: 10.1242/dev.01945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bates CM. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in kidney development. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1373–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1747-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dudley AT, Lyons KM, Robertson EJ. A requirement for bone morphogenetic protein-7 during development of the mammalian kidney and eye. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2795–2807. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blank U, Brown A, Adams DC, et al. BMP7 promotes proliferation of nephron progenitor cells via a JNK-dependent mechanism. Development. 2009;136:3557–3566. doi: 10.1242/dev.036335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mori K, Yang J, Barasch J. Ureteric bud controls multiple steps in the conversion of mesenchyme to epithelia. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2003;14:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(03)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halt K, Vainio S. Coordination of kidney organogenesis by Wnt signaling. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:737–744. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2733-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barasch J, Yang J, Ware CB, et al. Mesenchymal to epithelial conversion in rat metanephros is induced by LIF. Cell. 1999;99:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81524-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plisov SY, Yoshino K, Dove LF, et al. TGF beta 2, LIF and FGF2 cooperate to induce nephrogenesis. Development. 2001;128:1045–1057. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herzlinger D, Qiao J, Cohen D, et al. Induction of kidney epithelial morphogenesis by cells expressing Wnt-1. Dev Biol. 1994;166:815–818. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stark K, Vainio S, Vassileva G, et al. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature. 1994;372:679–683. doi: 10.1038/372679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mandel H, Shemer R, Borochowitz ZU, et al. SERKAL syndrome: An autosomal-recessive disorder caused by a loss-of-function mutation in WNT4. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Biason-Lauber A, Konrad D, Navratil F, et al. A WNT4 mutation associated with Müllerian-duct regression and virilization in a 46,XX woman. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:792–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karner CM, Das A, Ma Z, et al. Canonical Wnt9b signaling balances progenitor cell expansion and differentiation during kidney development. Development. 2011;138:1247–1257. doi: 10.1242/dev.057646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park JS, Ma W, O’Brien LL, et al. Six2 and Wnt regulate self-renewal and commitment of nephron progenitors through shared gene regulatory networks. Dev Cell. 2012;23:637–651. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park JS, Valerius MT, McMahon AP. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates nephron induction during mouse kidney development. Development. 2007;134:2533–2539. doi: 10.1242/dev.006155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Karavanova ID, Dove LF, Resau JH, et al. Conditioned medium from a rat ureteric bud cell line in combination with bFGF induces complete differentiation of isolated metanephric mesenchyme. Development. 1996;122:4159–4167. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Romio L, Wright V, Price K, et al. OFD1, the gene mutated in oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1, is expressed in the metanephros and in human embryonic renal mesenchymal cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:680–689. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000054497.48394.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Price KL, Long DA, Jina N, et al. Microarray interrogation of human metanephric mesenchymal cells highlights potentially important molecules in vivo. Physiol Genomics. 2007;28:193–202. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00147.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meijer L, Skaltsounis AL, Magiatis P, et al. GSK-3-selective inhibitors derived from Tyrian purple indirubins. Chem Biol. 2003;10:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levinson RS, Batourina E, Choi C, et al. Foxd1-dependent signals control cellularity in the renal capsule, a structure required for normal renal development. Development. 2005;132:529–539. doi: 10.1242/dev.01604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hatini V, Huh SO, Herzlinger D, et al. Essential role of stromal mesenchyme in kidney morphogenesis revealed by targeted disruption of winged helix transcription factor BF-2. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1467–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reginensi A, Scott RP, Gregorieff A, et al. Yap- and Cdc42-dependent nephrogenesis and morphogenesis during mouse kidney development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Das A, Tanigawa S, Karner CM, et al. Stromal-epithelial crosstalk regulates kidney progenitor cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ncb2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buzhor E, Omer D, Harari-Steinberg O, et al. Reactivation of NCAM1 defines a subpopulation of human adult kidney epithelial cells with clonogenic and stem/progenitor properties. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1621–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bussolati B, Bruno S, Grange C, et al. Isolation of renal progenitor cells from adult human kidney. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:545–555. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sagrinati C, Netti GS, Mazzinghi B, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman’s capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lindgren D, Boström AK, Nilsson K, et al. Isolation and characterization of progenitor-like cells from human renal proximal tubules. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:828–837. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bussolati B, Moggio A, Collino F, et al. Hypoxia modulates the undifferentiated phenotype of human renal inner medullary CD133+ progenitors through Oct4/miR-145 balance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F116–F128. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00184.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gupta S, Verfaillie C, Chmielewski D, et al. Isolation and characterization of kidney-derived stem cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3028–3040. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smeets B, Boor P, Dijkman H, et al. Proximal tubular cells contain a phenotypically distinct, scattered cell population involved in tubular regeneration. J Pathol. 2013;229:645–659. doi: 10.1002/path.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kusaba T, Lalli M, Kramann R, et al. Differentiated kidney epithelial cells repair injured proximal tubule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:1527–1532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310653110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lowry WE, Richter L, Yachechko R, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from dermal fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2883–2888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711983105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim D, Dressler GR. Nephrogenic factors promote differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into renal epithelia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3527–3534. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Osafune K, Nishinakamura R, Komazaki S, et al. In vitro induction of the pronephric duct in Xenopus explants. Dev Growth Differ. 2002;44:161–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2002.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vigneau C, Polgar K, Striker G, et al. Mouse embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies generate progenitors that integrate long term into renal proximal tubules in vivo. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1709–1720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bruce SJ, Rea RW, Steptoe AL, et al. In vitro differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells toward a renal lineage. Differentiation. 2007;75:337–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Song B, Smink AM, Jones CV, et al. The directed differentiation of human iPS cells into kidney podocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Taguchi A, Nishinakamura R. Nephron reconstitution from pluripotent stem cells. Kidney Int. 2015;87:894–900. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takasato M, Er PX, Becroft M, et al. Directing human embryonic stem cell differentiation towards a renal lineage generates a self-organizing kidney. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:118–126. doi: 10.1038/ncb2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Montserrat N, Ramírez-Bajo MJ, Xia Y, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human renal proximal tubular cells with only two transcription factors, OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24131–24138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.350413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhou T, Benda C, Dunzinger S, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from urine samples. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:2080–2089. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chang CH, Davies JA. An improved method of renal tissue engineering, by combining renal dissociation and reaggregation with a low-volume culture technique, results in development of engineered kidneys complete with loops of Henle. Nephron, Exp Nephrol. 2012;121:e79–e85. doi: 10.1159/000345514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xinaris C, Benedetti V, Rizzo P, et al. In vivo maturation of functional renal organoids formed from embryonic cell suspensions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1857–1868. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012050505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nightingale SJ, Hollis RP, Pepper KA, et al. Transient gene expression by nonintegrating lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2006;13:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science. 2008;322:945–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1162494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Song JJ, Guyette JP, Gilpin SE, et al. Regeneration and experimental orthotopic transplantation of a bioengineered kidney. Nat Med. 2013;19:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nm.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]