Abstract

The Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) Case Registry was established in 2010 by the American College of Medical Toxicology. The Registry includes all medical toxicology consultations performed at participating sites. The Registry was queried for all cases entered between January 1 and December 31, 2014. Specific data reviewed for analysis included demographics (age, gender, ethnicity), source of consultation, reasons for consultation, agents involved in toxicological exposures, signs, symptoms, clinical findings, fatalities, and treatment. In 2014, 9172 cases were entered in the Registry across 47 active member sites. Females accounted for 51.1 % of cases. The majority (65.1 %) of cases were adults between the ages of 19 and 65. Caucasians made up the largest identified ethnic group (48.9 %). Most Registry cases originated from the inpatient setting (93.5 %), with a large majority of these consultations coming from the emergency department or inpatient admission services. Intentional and unintentional pharmaceutical exposures continued to be the most frequent reasons for consultation, accounting for 61.7 % of cases. Among cases of intentional pharmaceutical exposure, 62.4 % were associated with a self-harm attempt. Non-pharmaceutical exposures accounted for 14.1 % of Registry cases. Similar to the past years, non-opioid analgesics, sedative-hypnotics, and opioids were the most commonly encountered agents. Clinical signs or symptoms were noted in 81.9 % of cases. There were 89 recorded fatalities (0.97 %). Medical treatment (e.g., antidotes, antivenom, chelators, supportive care) was rendered in 62.3 % of cases. Patient demographics and exposure characteristics in 2014 Registry cases remain similar to prior years. The majority of consultations arose in the acute care setting (emergency department or inpatient) and involved exposures to pharmaceutical products. Among exposures, non-opioid analgesics, sedative/hypnotics, and opioids were the most frequently encountered. A majority of cases required some form of treatment, but fatalities were rare.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13181-015-0507-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Poisonings, Overdose, Surveillance, Epidemiology

Introduction

The American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) created the Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) in 2010 as a means to provide a tool for clinical toxicology research and toxico-surveillance [1]. Unlike other poisoning databases, ToxIC cases are prospective and based on patients seen in clinical consultation by medical toxicologists in both inpatient and ambulatory settings. Beginning with four sites in 2010, the ToxIC registry has since expanded, including eight sites added in 2014. Investigators from 47 active sites, involving 77 separate facilities, submitted cases in 2014. Currently, 80.7 % of the active accredited medical toxicology fellowship programs in the USA participate in the ACMT ToxIC Registry. The objective of this report is to summarize the Registry’s 2014 data. Cases entered from January 1, 2014 through December 31, 2014 are described in this fifth annual report for the Registry [2–5].

Since its inception, several supplemental or subregistries have been created within ToxIC. In 2014, subregistries focusing on novel drugs of abuse and metal-on-metal hip implants were added. These, in addition to existing supplemental registries studying caustic ingestion, lipid resuscitation therapy, prescription drug misuse, snake bites, and a clinical poisoning severity score, bring the total number of current subregistries active in 2014 to seven. Additional changes to the Registry data include more detailed patient demographic information and further specification of reasons for exposures to medications or other chemical substances. In 2014, 18 abstracts based on Registry data were presented at three national meetings and three manuscripts utilizing Registry data were published [5–7].

In addition to the support from ACMT, extramural funding for the Registry came from both governmental and industry sources in 2014. Government funding was provided via three National Institute of Health (NIH) grant subawards, while industry funding was in the form of an unrestricted grant from BTG International Inc. (North America) utilized for the support of the North American Snakebite Registry.

Methods

Participating investigators agree to enter data on all medical toxicology consultations into the Registry. Cases are entered on a password-protected, online data collection form. The site is maintained by ACMT with oversight by the ToxIC Registry Steering Committee. The Registry is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and does not collect any protected health information or otherwise identifying patient data fields. Registry participation is compliant with local Institutional Review Board policies and procedures, as well as the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB). WIRB has determined that the collection protocol based on submission of de-identified data from a clinical visit under the maintenance and control of the medical toxicologist does not meet the threshold of human subjects research under federal regulation 45 CFR 46 and associated guidance.

Collected data include presenting signs, symptoms, clinical course, treatments, limited patient demographics, outcome, and the type of and reason for toxicological exposure. The term “consultation” is used in this report to describe any encounter with a medical toxicologist. Such encounters may include admission to a toxicology inpatient service or evaluation by a medical toxicologist in the emergency department, inpatient unit, or outpatient clinic. The online collection form is formatted to ensure data remains organized and easily searchable. Free-text entry fields allow caregivers to provide further detail or supplementary information. As part of the Registry’s mission of providing a real-time toxico-surveillance tool, a component of the standard data form is a sentinel detection field that signals novel or unusual cases.

For this report, a search of the database was performed to identify cases recorded from January 1, 2014 through December 31, 2014. Additional data from the subregistries will be published separately.

This descriptive report summarizes case demographics, source and location of consultation, and reason for encounter and provides proportion of cases by individual agent, agent class, and treatment provided. Summary statistics for cases involving fatalities and adverse drug reactions are also described. In the following tables describing individual agent or agent classes, unless otherwise indicated, values with fewer than five occurrences were not listed as separate items, but are further grouped in “Miscellaneous.” Percentages noted in tables for individual agents represent their relative proportion within their respective agent class. For clinical signs or symptoms, the tables provide the percentage of any individual signs or symptom relative to the total number of registry cases. In the detailed treatment tables, percentages for each treatment modality represent the relative frequency among the subset of cases receiving at least one type of treatment. In instances of limited data for an entire class or clinical effects (e.g., such as ten or fewer cases overall or one agent contributing the majority (>80 %) of a class), no detailed table is presented, but information may be described in the text section or available in the Supplementary Material.

Results

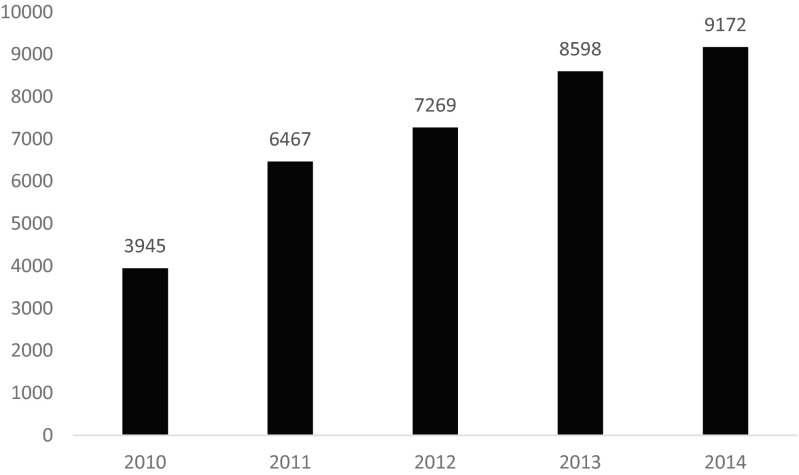

Tables 1 and 2, respectively, show the state and city (country and city for non-US sites) listings of the individual institutions participating in the ACMT ToxIC Registry. Institutions varied substantially in the number of cases entered in 2014, ranging from 1 to 833 cases submitted for this reporting year. The growth in annual case counts continued in 2014 (Fig. 1). The 47 ToxIC member sites active in 2014 entered a total of 9172 cases across 77 individual clinical facilities, representing a 6.7 % increase over 2013.

Table 1.

Participating institutions providing cases in 2014—USA

| Arizona | Massachusetts | Oregon |

| Phoenix | Worcester | Portland |

| Banner Good Samaritan | UMass Memorial Medical Center | Doernbecher Children’s Hospital |

| Phoenix Children’s Hospital | Michigan | Oregon Health and Science University Hospital |

| California | Grand Rapids | Oregon Occupational Toxicology |

| Fresno | Spectrum Health Hospitals | Pennsylvania |

| UCSF Fresno Medical Center | Minnesota | Harrisburg |

| Loma Linda | St. Paul | Harrisburg Hospital |

| Children’s Hospital Boston | Regions Hospital | JC Blair Memorial Hospital |

| Los Angeles | Missouri | Philadelphia |

| University of Southern California Verdugo Hills | Kansas City | Einstein Medical Center |

| San Diego | Children’s Mercy Hospitals & Clinics | Hahnemann University Hospital |

| Kaiser San Diego | St. Louis | Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital |

| San Francisco | Washington University School of Medicine | Mercy Hospital of Philadelphia |

| San Francisco General Hospital | Nebraska | St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children |

| Colorado | Omaha | Pittsburgh |

| Denver | University of Nebraska Medical Center | UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh |

| Children’s Hospital Colorado | New Jersey | UPMC Magee Women’s Hospital |

| Denver Health Medical Center | Morristown | UPMC Presbyterian/Shadyside |

| Porter and Littleton Adventist Hospital | Morristown Medical Center | Texas |

| Swedish Medical Center | New Brunswick | Dallas |

| University of Colorado Medical Center | Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital | Children’s Medical Center Dallas |

| Connecticut | Newark | Parkland Memorial Hospital |

| Hartford | New Jersey Medical School (Rutgers) | St Paul University Hospital (UT) |

| Connecticut Children’s Medical Center | New Mexico | University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical |

| Hartford Hospital | Albuquerque | Houston |

| John Dempsey Hospital | University of New Mexico Hospital | Ben Taub General Hospital |

| Georgia | New York | Texas Children’s Hospital |

| Atlanta | Manhasset | San Antonio |

| Grady Memorial Hospital | Long Island Jewish Medical Center | San Antonio Military Medical Center |

| Illinois | North Shore University Hospital | Utah |

| Chicago | Staten Island University Hospital | Salt Lake City |

| UIC Medical Center | New York | Primary Children’s Hospital |

| Evanston | Bellevue Medical Center | University of Utah Hospital |

| Evanston North Shore University Health System | Mount Sinai Hospital | Virginia |

| Indiana | NYU Langone Medical Center | Charlottesville |

| Indianapolis | Rochester | University of Virginia Health Systems |

| IU-Indiana University Hospital | Highland Hospital | Richmond |

| IU-Methodist Hospital-Indianapolis | Huther-Doyle | Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Medical |

| IU-Riley Hospital for Children | Strong Memorial Hospital | Wisconsin |

| IU-Wishard Memorial Hospital | Syracuse | Milwaukee |

| Massachusetts | SUNY Upstate Medical University | Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin |

| Boston | North Carolina | Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital |

| Beth Israel Boston | Charlotte | |

| Carolinas Medical Center |

Table 2.

Participating institutions providing cases—international

| Australia |

| Melbourne |

| Austin Hospital |

| Sydney |

| Sydney-Blacktown-Mt. Druitt Health |

| Canada |

| Toronto |

| Hospital for Sick Children |

| Israel |

| Haifa |

| Rambam Health Care Campus |

| Saudi Arabia |

| Riyadh |

| King Abdulaziz Medical City |

ToxIC maintains a related Registry of other international sites not reflected in this report

Fig. 1.

ACMT ToxIC Registry total case count by year, 2010–2014

Demographics

Tables 3 and 4 summarize case demographic data for gender, age, race, and Hispanic ethnicity. In 2014, females comprised a slight majority of the Registry cases: 4691 (51.1 %) to 4481 (48.9 %), females to males, respectively. Sixty female cases were identified as being pregnant (1.3 %), accounting for 0.7 % of all cases. Adults between the ages of 19 and 65 comprised the majority (65.1 %) of reported cases. Adolescents (13 to 18 years) were the next most frequent age category at 17.1 % of the cases. Data fields to establish race and Hispanic ethnicity information were newly introduced to the Registry in August 2014. Table 3 summarizes the available race/ethnicity data for this subset of cases (N = 4759 field eligible). Caucasians made up the largest identified race group at 48.9 %.

Table 3.

ToxIC case demographics—age and gender

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 4481 (48.9) |

| Female | 4691 (51.1) |

| Pregnant | 60 (0.7) |

| Age (years) | |

| 2–6 | 442 (4.8) |

| 7–12 | 243 (2.6) |

| 13–18 | 1567 (17.1) |

| 19–65 | 5968 (65.1) |

| 66–89 | 548 (6.0) |

| >89 | 29 (0.3) |

| Unknown | 29 (0.3) |

| Total | 9172 (100) |

Table 4.

ToxIC case demographics—race and Hispanic ethnicity

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 2369 (48.9) |

| Unknown/uncertain | 1563 (32.8) |

| Black/African | 449 (9.4) |

| Other | 230 (4.8) |

| Asian | 86 (1.8) |

| Multiple | 51 (1.1) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 48 (1.0) |

| Australian Aboriginal | <5 (<0.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | <5 (<0.1) |

| Hispanic ethnicitya | |

| Hispanic | 450 (9.5) |

| Non-Hispanic | 2654 (55.8) |

| Unknown | 1402 (29.5) |

| Total | 9172 (100) |

Race/ethnicity counts and frequency derived from 4759 cases with available data after July 2014 (51.9 % of the total number of cases in 2014)

aHispanic ethnicity as indicated exclusive of race

Source of Referral and Primary Reason for Encounter

Hospital emergency departments were the most frequent source of referral, accounting for 5607 (61.1 %) of all Registry cases combined. The vast majority of all ToxIC cases (93.5 %) were seen in the emergency department (ED) or as an inpatient (IP) (N = 8570), with an order of magnitude fewer seen as outpatients (N = 602 or 6.6 %). As shown on Table 5, ED/IP consultation referrals came via the ED (N = 5590 or 65.2 % of ED/IP cases), admitting services (N = 2036 or 23.8 %), with a limited number from outside hospital transfer or other hospital non-ED service request (N = 901 or 10.5 %). In comparison, outpatient (OP) referrals were primarily via patient self-referral (N = 264 or 43.9 % of OP cases) or primary care/other provider referrals (N = 221 or 36.7 %). Poison center referrals accounted for 4.8 % of the OP and 0.1 % of the ED/IP referrals in 2014.

Table 5.

ToxIC registry case referral sources by inpatient/outpatient status

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Emergency department (ED) or inpatient (IP)a | |

| ED | 5590 (65.2) |

| Admitting service | 2036 (23.8) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 632 (7.4) |

| Request from another hospital service (not ED) | 269 (3.1) |

| Primary care provider/other OP treating physician | 26 (0.3) |

| Poison center | 12 (0.1) |

| Employer/independent med evaluation/workman’s comp | <5 (<0.1) |

| Self-referral | <5 (<0.1) |

| ED/IP total | 8570 (100) |

| Outpatient (OP)/clinic/office consultationb | |

| Self-referral | 264 (43.9) |

| Primary care provider or other OP treating physician | 221 (36.7) |

| Employer/independent med eval/workman’s comp | 65 (10.8) |

| Poison center | 29 (4.8) |

| ED | 17 (2.8) |

| Request from another hospital service (not ED) | <5 (<0.9) |

| Admitting service | <5 (<0.9) |

| OP total | 602 (100) |

aPercentage based on the total number of cases (N = 8570) seen by a medical toxicologist as consulting (ED or IP) or as attending (IP)

bPercentage based on the total number of cases (N = 602) seen by a medical toxicologist as outpatient, clinic visit, or office consultation

Exposure to pharmaceutical products, both intentional and unintentional, was the most common reason for consultation, accounting for 61.7 % of all consultations (Table 6). By comparison, exposure to non-pharmaceuticals accounted for 14.1 %. All types of withdrawal combined were reported as the primary reason for encounter in 6.3 % or 575 cases, while all types of envenomation resulted 3.3 % or 304 cases. In 2014, additional data fields were added to the Registry for cases of intentional pharmaceutical exposure in order to further specify the presence of self-harm or suicidal intent. Within this subset of 4802 cases, self-harm attempt was reported in 2996 (62.4 %), with suicidal intent reported in 2327 (48.4 %) (Table 7).

Table 6.

Reasons for medical toxicology encounter/consultation

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Intentional exposure—pharmaceutical | 4803 (52.4) |

| Intentional exposure—non-pharmaceutical | 913 (10.0) |

| Unintentional exposure—pharmaceutical | 853 (9.3) |

| Unintentional exposure—non-pharmaceutical | 379 (4.1) |

| Organ system dysfunction | 347 (3.8) |

| Not documented | 297 (3.2) |

| Withdrawal—opioids | 270 (2.9) |

| Envenomation—snake | 234 (2.6) |

| Withdrawal—ethanol | 227 (2.5) |

| Ethanol abuse | 194 (2.1) |

| Interpretation of toxicology data | 180 (2.0) |

| Environmental evaluation | 162 (1.8) |

| Occupational evaluation | 130 (1.4) |

| Withdrawal—sedative/hypnotic | 51 (0.6) |

| Envenomation—spider | 46 (0.5) |

| Malicious/criminal | 27 (0.3) |

| Withdrawal—other | 19 (0.2) |

| Envenomation—scorpion | 15 (0.2) |

| Envenomation—other | 9 (0.1) |

| Withdrawal—cocaine/amphetamine | 8 (0.1) |

| Marine | 7 (0.1) |

| Adverse drug reaction | <5 (<0.01) |

| Total | 9172 (100) |

Table 7.

Detailed reasons for encounter—intentional pharmaceutical exposure

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Reason for intentional pharmaceutical exposure subgroupa | |

| Attempt at self-harm | 2996 (62.4) |

| Abuse/misuse | 796 (16.6) |

| Therapeutic use | 465 (9.7) |

| Unknown | 384 (8.0) |

| None listed | 161 (3.4) |

| 4802 (100) | |

| Attempt at self-harm—suicidal intent subclassificationb | |

| Suicidal intent | 2327 (77.7) |

| Suicidal intent unknown | 277 (9.2) |

| No data entered for suicidal intent | 259 (8.6) |

| No data entered for suicidal intent | 133 (4.4) |

| 2996 (100) | |

aPercentage of total number of cases (N = 4802) indicating primary reason for encounter due to intentional pharmaceutical exposure

bPercentage of number of cases indicating attempt at self-harm (N = 2996)

Agent Classes

A total of 12,496 individual agents were listed among the 8040 Registry cases reporting a toxicological exposure. Reporting medical toxicologists indicated no suspected toxicological exposure in the remainder of cases (12.4 %). The distribution of these agents among the Registry’s 40 predefined substance classes is shown in Table 8. Exposure to more than one agent was reported in 2755 (30.0 %) of cases. Similar to 2013 Registry data, non-opioid analgesics, sedative/hypnotic agents, opioids, and antidepressants constituted the most commonly encountered substance classes, collectively accounting for nearly one half (46.1 %) of all agents reported in 2014. Eight agent classes contributed to 37.7 % of the total cases: ethanol (6.8 %), anticholinergic/antihistamine (6.1 %), cardiovascular (5.7 %), antipsychotic (5.5 %), sympathomimetic (5.5 %), anticonvulsant (3.4 %), psychoactive (2.5 %), and envenomation (2.3 %). Table 8 provides comparative data from prior years of the Registry (2010–2013), again as the case number and relative frequency by agent class. Several classes have been added since 2010 as noted by “NR” in earlier years, including both pharmaceuticals (e.g., cough and cold, anticoagulant, other pharmaceutical, Parkinson’s medication) and non-pharmaceuticals (e.g., household products, rodenticides).

Table 8.

Agent classes involved in medical toxicology consultation

| 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Analgesic (nonopioid) | 1599 (12.8) | 1490 (13.2) | 1295 (12.3) | 1368 (12.3) | 854 (14.8) |

| Sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxant | 1546 (12.4) | 1383 (12.3) | 1422 (13.5) | 1492 (13.4) | 783 (13.6) |

| Opioid | 1311 (10.5) | 1250 (11.1) | 1086 (10.3) | 1100 (9.9) | 619 (10.7) |

| Antidepressant | 1301 (10.4) | 1056 (9.4) | 1039 (9.8) | 1029 (9.3) | 659 (11.4) |

| Ethanol | 849 (6.8) | 737 (6.5) | 850 (8.1) | 580 (5.2) | 371 (6.4) |

| Anticholinergic/antihistamine | 761 (6.1) | 617 (5.5) | 457 (4.3) | 549 (4.9) | 378 (6.5) |

| Cardiovascular | 713 (5.7) | 687 (6.1) | 616 (5.8) | 631 (5.7) | 334 (5.8) |

| Antipsychotic | 689 (5.5) | 626 (5.6) | 551 (5.2) | 587 (5.3) | 366 (6.3) |

| Sympathomimetic | 684 (5.5) | 702 (6.2) | 692 (6.6) | 774 (7.0) | 247 (4.3) |

| Anticonvulsant | 421 (3.4) | 408 (3.6) | 339 (3.2) | 451 (4.1) | 218 (3.8) |

| Psychoactive | 312 (2.5) | 302 (2.7) | 460 (4.4) | 360 (3.2) | 135 (2.3) |

| Envenomation | 282 (2.3) | 188 (1.7) | 196 (1.9) | 183 (1.6) | 105 (1.8) |

| Diabetic medications | 210 (1.7) | 181 (1.6) | 138 (1.3) | 113 (1.0) | 65 (1.1) |

| Lithium | 179 (1.4) | 166 (1.5) | 133 (1.3) | 100 (0.9) | 78 (1.4) |

| Cough and cold products | 161 (1.3) | 134 (1.2) | NR | NR | NR |

| Herbal products/dietary supplements | 159 (1.3) | 119 (1.1) | 50 (0.5) | 76 (0.7) | 48 (0.8) |

| Metals | 145 (1.2) | 154 (1.4) | 227 (2.2) | 322 (2.9) | 154 (2.7) |

| Gases/irritants/vapors/dusts | 138 (1.1) | 126 (1.1) | 129 (1.2) | 169 (1.5) | 63 (1.1) |

| Household product | 125 (1.0) | 113 (1.0) | NR | NR | NR |

| Unknown agent | 109 (0.9) | 88 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR |

| Antimicrobial | 104 (0.8) | 113 (1.0) | 62 (0.6) | 107 (1.0) | 38 (0.7) |

| Toxic alcohol | 104 (0.8) | 95 (0.8) | 121 (1.1) | 145 (1.3) | 93 (1.6) |

| Hydrocarbon | 84 (0.7) | 84 (0.8) | 45 (0.4) | 67 (0.6) | 50 (0.9) |

| Caustic | 80 (0.6) | 88 (0.8) | 47 (0.4) | 93 (0.8) | 45 (0.8) |

| Plants and fungi | 75 (0.6) | 71 (0.6) | 52 (0.5) | 78 (0.7) | 18 (0.3) |

| Anticoagulant | 64 (0.5) | 58 (0.5) | NR | NR | NR |

| Endocrine | 43 (0.3) | 34 (0.3) | 49 (0.5) | 37 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) |

| Other non-pharmaceutical product | 39 (0.3) | 14 (0.1) | NR | NR | NR |

| Chemotherapeutic/immunological | 37 (0.3) | 23 (0.2) | 12 (0.1) | 20 (0.2) | 5 (0.1) |

| Rodenticide | 35 (0.3) | 15 (0.1) | NR | NR | NR |

| Gastrointestinal agents | 33 (0.3) | 34 (0.3) | 30 (0.3) | 50 (0.4) | 14 (0.2) |

| Insecticide | 30 (0.2) | 27 (0.2) | NR | NR | NR |

| Other pharmaceutical product | 25 (0.2) | 30 (0.3) | NR | NR | NR |

| Anesthetic | 19 (0.2) | 11 (0.1) | 30 (0.3) | 21 (0.2) | 16 (0.3) |

| Anti-parkinsonism drugs | 9 (0.1) | 19 (0.2) | NR | NR | NR |

| Pulmonary | 9 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 16 (0.2) | 17 (1.5) | 9 (0.2) |

| Ingested foreign object | 6 (0.05) | <5 (<0.03) | NR | NR | NR |

| Herbicide | 5 (0.04) | 11 (0.1) | NR | NR | NR |

| Fungicide | <5 (<0.03) | <5 (<0.03) | NR | NR | NR |

| WMD/riot agent/radiological | <5 (<0.03) | <5 (<0.03) | <5 (<0.03) | 7 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total annual agent entries | 12,496 | 11,279 | 10,553 | 11,119 | 5774 |

Percentages are out of the total number of reported agent entries per year; 30 % of 2014 Registry cases reported exposure to multiple agents

NR no cases reported, class category not available

Individual Agents by Class

Tables 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25 summarize specific pharmaceuticals and other substances reported as a toxic exposure by class, in order, based on relative contribution to the total number of agents reported to the Registry, with two exceptions. Single agent classes for ethanol and lithium are instead presented and discussed with toxic alcohols and anticonvulsants, respectively. Additional detailed information for agent classes with relatively smaller case numbers and/or individual agents may be found in the online Supplementary Material.

Table 9.

Analgesics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | 1051 (64.6) |

| Aspirin | 270 (16.9) |

| Ibuprofen | 194 (12.1) |

| Naproxen | 52 (3.3) |

| Salicylamide | 8 (0.5) |

| Meloxicam | 7 (0.4) |

| Methylsalicylate | 5 (0.3) |

| Miscellaneousa | 12 (0.8) |

| Class total | 1599 (100) |

aIncludes ketorolac, NSAID unspecified, phenazopyridine, analgesic unspecified, diclofenac, indomethacin, metamizole, piroxicam, and salsalate

Table 10.

Sedative-hypnotics/muscle relaxants by subtype

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | 843 (54.5) |

| Clonazepam | 320 (20.7) |

| Alprazolam | 234 (15.1) |

| Lorazepam | 127 (8.2) |

| Diazepam | 80 (5.2) |

| Benzodiazepine unspecified | 36 (2.3) |

| Temazepam | 20 (1.3) |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 13 (0.8) |

| Miscellaneousa | 13 (0.8) |

| Muscle relaxants | 320 (20.7) |

| Cyclobenzaprine | 116 (7.5) |

| Carisoprodol | 78 (5.0) |

| Baclofen | 76 (4.9) |

| Tizanidine | 24 (1.6) |

| Methocarbamol | 10 (0.6) |

| Metaxalone | 6 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousb | 10 (0.6) |

| Other sedatives | 193 (12.5) |

| Gabapentin | 115 (7.4) |

| Pregabalin | 35 (2.3) |

| Buspirone | 23 (1.5) |

| Sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxant unspecified | 9 (0.6) |

| Propofol | 7 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneousc | <5 (<0.4) |

| Non-benzodiazepine agonists (“Z” drugs) | 138 (8.9) |

| Zolpidem | 126 (8.2) |

| Eszopiclone | 7 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneousd | 5 (0.3) |

| Barbiturates | 52 (3.4) |

| Butalbital | 37 (2.4) |

| Phenobarbital | 12 (0.8) |

| Miscellaneouse | <5 (<0.3) |

| Class total | 1546 (100) |

aIncludes midazolam, nitrazepam, bromazepam, oxazepam, etizolam, and flunitrazepam

bIncludes meprobamate, chlorzoxazone, and orphenadrine

cIncludes phenibut, chlorbutol, and ramelteon

dIncludes zopiclone and zaleplon

eIncludes pentobarbital and butabarbital

Table 11.

Opioids

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Heroin | 350 (26.7) |

| Oxycodone | 244 (18.6) |

| Methadone | 158 (12.1) |

| Hydrocodone | 128 (9.8) |

| Tramadol | 124 (9.5) |

| Buprenorphine | 80 (6.1) |

| Opioid unspecified | 54 (4.1) |

| Morphine | 52 (4.0) |

| Fentanyl | 38 (2.9) |

| Codeine | 30 (2.3) |

| Hydromorphone | 15 (1.1) |

| Oxymorphone | 12 (0.9) |

| Naltrexone | 7 (0.5) |

| Loperamide | 5 (0.4) |

| Naloxone | 5 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousa | 9 (0.7) |

| Class total | 1311 (100) |

aIncludes tapentadol, diphenoxylate, desomorphine, and papaverine

Table 12.

Antidepressants

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Other antidepressants | 485 (37.3) |

| Bupropion | 230 (17.7) |

| Trazodone | 180 (13.8) |

| Mirtazapine | 62 (4.8) |

| Vilazodone | 6 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneousa | 7 (0.5) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | 480 (36.9) |

| Citalopram | 135 (10.4) |

| Sertraline | 114 (8.8) |

| Fluoxetine | 109 (8.4) |

| Escitalopram | 78 (6.0) |

| Paroxetine | 44 (3.4) |

| Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) | 176 (13.5) |

| Amitriptyline | 129 (9.9) |

| Nortriptyline | 20 (1.5) |

| Doxepin | 18 (1.4) |

| Imipramine | 5 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousb | <5 (0.1) |

| Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) | 150 (11.5) |

| Venlafaxine | 89 (6.8) |

| Duloxetine | 47 (3.6) |

| Desvenlafaxine | 7 (0.5) |

| Fluvoxamine | 7 (0.5) |

| Class total | 1301 (100) |

aIncludes antidepressant unspecified, nefazodone, tianeptine, and tranylcypromine

bIncludes clomipramine and desipramine

Table 13.

Anticholinergics and antihistamines

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Diphenhydramine | 406 (53.4) |

| Hydroxyzine | 110 (14.5) |

| Doxylamine | 45 (5.9) |

| Chlorpheniramine | 42 (5.5) |

| Benztropine | 37 (4.9) |

| Promethazine | 26 (3.4) |

| Cetirizine | 16 (2.1) |

| Loratadine | 13 (1.7) |

| Antihistamine unspecified | 7 (0.9) |

| Trihexyphenidyl | 7 (0.9) |

| Dimenhydrinate | 6 (0.8) |

| Oxybutynin | 6 (0.8) |

| Anticholinergic unspecified | 5 (0.6) |

| Dicyclomine | 5 (0.6) |

| Meclizine | 5 (0.6) |

| Miscellaneousa | 25 (3.3) |

| Class total | 761 (100) |

aIncludes fexofenadine, hyoscyamine, atropine, brompheniramine, scopolamine, belladonna, fesoterodine, pheniramine, pyrilamine, tiotropium, and tolterodine

Table 14.

Cardiovascular agents by subtype

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Beta blockers | 196 (27.5) |

| Metoprolol | 76 (10.7) |

| Propranolol | 49 (6.9) |

| Carvedilol | 27 (3.8) |

| Atenolol | 23 (3.2) |

| Labetalol | 8 (1.1) |

| Nadolol | 6 (0.8) |

| Miscellaneousa | 7 (1.0) |

| Sympatholytics | 160 (22.4) |

| Clonidine | 130 (18.2) |

| Guanfacine | 30 (4.2) |

| Calcium channel antagonists | 107 (15.0) |

| Amlodipine | 53 (7.4) |

| Diltiazem | 28 (3.9) |

| Verapamil | 21 (2.9) |

| Miscellaneousb | 5 (0.7) |

| Cardiac glycosides | 70 (9.8) |

| Digoxin | 69 (9.7) |

| Digitoxin | <5 (<0.2) |

| ACE inhibitors | 57 (8.0) |

| Lisinopril | 53 (7.4) |

| Miscellaneousc | 5 (0.6) |

| Diuretics | 44 (6.2) |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 21 (2.9) |

| Furosemide | 13 (1.8) |

| Miscellaneousd | 10 (1.4) |

| Other antihypertensives and vasodilators | 28 (3.9) |

| Prazosin | 10 (1.4) |

| Miscellaneouse | 18 (2.5) |

| Antidysrhythmics | 20 (2.8) |

| Amiodarone | 6 (0.8) |

| Flecainide | 5 (0.7) |

| Miscellaneousf | 9 (1.3) |

| Other cardiovascular agents | 17 (2.4) |

| Simvastatin | 10 (1.4) |

| Miscellaneousg | 7 (1.0) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 15 (2.1) |

| Losartan | 8 (1.1) |

| Valsartan | 5 (0.7) |

| Miscellaneoush | <5 (<0.4) |

| Class total | 713 (100) |

aIncludes nebivolol and timolol

bIncludes nifedipine and felodipine

cIncludes benazepril, perindopril, and quinapril

dIncludes chlorthalidone, acetazolamide, bumetanide, spironolactone, and torsemide

eIncludes tamsulosin, isosorbide, antihypertensive unspecified, hydralazine, terazosin, alfuzosin, cilostazol, doxazosin, minoxidil, and nitroglycerin

fIncludes propafenone, mexiletine, dofetilide, and dronederone

gIncludes atorvastatin, colesevalm, fenofibrate, lovastatin, and ranolazine

hIncludes olmesartan and telmisartan

Table 15.

Antipsychotics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Quetiapine | 331 (48.0) |

| Risperidone | 80 (11.6) |

| Aripiprazole | 76 (11.0) |

| Olanzapine | 73 (10.6) |

| Haloperidol | 35 (5.1) |

| Clozapine | 23 (3.3) |

| Ziprasidone | 19 (2.8) |

| Chlorpromazine | 18 (2.6) |

| Paliperidone | 9 (1.3) |

| Lurasidone | 8 (1.2) |

| Miscellaneousa | 17 (2.2) |

| Class total | 689 (100) |

aIncludes prochlorperazine, fluphenazine, loxapine, antipsychotic unspecified, trifluoperazine, asenapine, iloperidone, and thioridazine

Table 16.

Sympathomimetics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Cocaine | 252 (37.1) |

| Methamphetamine | 145 (21.3) |

| Amphetamine | 77 (11.3) |

| Methylphenidate | 50 (7.4) |

| Dextroamphetamine | 33 (4.9) |

| Methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine | 26 (3.8) |

| Lisdexamfetamine | 18 (2.6) |

| Phenylephrine | 15 (2.2) |

| Phentermine | 14 (2.1) |

| Sympathomimetic unspecified | 10 (1.5) |

| 25I-NBOMe | 6 (0.9) |

| Atomoxetine | 6 (0.9) |

| Cathinone | 6 (0.9) |

| Dexmethylphenidate | 6 (0.9) |

| Miscellaneousa | 20 (2.9) |

| Class total | 684 (100) |

aIncludes clenbuterol, 2C series drugs, pseudoephedrine, epinephrine, alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone, ephedrine, ethylphenidate, methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA), phendimetrazine, phenylethylamine designer drugs, and tetrahydrozoline

Table 17.

Anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Lithiuma | 179 (100) |

| Valproic acid | 116 (27.6) |

| Lamotrigine | 94 (22.3) |

| Phenytoin | 59 (14.0) |

| Carbamazepine | 54 (12.8) |

| Topiramate | 42 (10.0) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 26 (6.2) |

| Levetiracetam | 16 (3.8) |

| Zonisamide | 7 (1.7) |

| Miscellaneousb | 7 (1.7) |

| Class total | 421 (100) |

aLithium is considered a separate agent class

bIncludes clobazam, felbamate, and lacosamide

Table 18.

Psychoactives

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Marijuana | 101 (32.4) |

| Cannabinoid—synthetic | 81 (26.0) |

| Phencyclidine | 27 (8.7) |

| Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) | 25 (8.0) |

| Nicotine | 21 (6.7) |

| Cannabinoid—nonsynthetic | 14 (4.5) |

| Gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB) | 13 (4.2) |

| Miscellaneousa | 30 (9.6) |

| Class total | 312 (100) |

aIncludes ketamine, donepezil, ibogaine, 1,4-butanediol, dimethyltryptamine, γ-butryolactone, mephedrone, methoxetamine, psychoactive unspecified, 2,6-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine, Argyeria nervosa, disulfiram, hallucinogen unspecified, hallucinogenic amphetamine, methylone, tetrahydropalmatine, and vareniciline

Table 19.

Envenomations and marine poisonings

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Crotalus spp. | 102 (36.2) |

| Agkistrodon spp. | 80 (28.4) |

| Snake unspecified | 30 (10.6) |

| Loxosceles spp. | 19 (6.7) |

| Latrodectus spp. | 18 (6.4) |

| Centruroides spp. | 13 (4.6) |

| Miscellaneousa | 20 (7.1) |

| Class total | 282 (100) |

aIncludes envenomation unspecified, Vipera palaesinae, scombroid poisoning, scorpion unspecified, ciguatera poisoning, hymenoptera, insect unspecified, jellyfish, Pterios spp. (lionfish), palytoxin, Scolopendra spp. (centipedes), spider unspecified, stingray, and Trimeresurus abolabris

Table 20.

Diabetic medications

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Metformin | 62 (29.5) |

| Insulin | 51 (24.3) |

| Glipizide | 39 (18.6) |

| Glyburide | 33 (15.7) |

| Glimepiride | 11 (5.2) |

| Sulfonylurea unspecified | 5 (2.4) |

| Miscellaneousa | 9 (4.3) |

| Class total | 210 (100) |

aIncludes sitagliptin, pioglitazone, gliclazide, liraglutide, and repaglinide

Table 21.

Ethanol and toxic alcohols

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Ethanola | 849 (100.0) |

| Nonethanol alcohols and glycols | |

| Ethylene glycol | 40 (38.5) |

| Isopropanol | 29 (27.9) |

| Methanol | 14 (13.5) |

| Acetone | 9 (8.7) |

| Miscellaneousb | 12 (11.5) |

| Class total | 104 (100) |

aEthanol is considered a separate agent class

bIncludes methyl ethyl ketone, propylene glycol, glycol ether unspecified, butyl ethylene glycol, and toxic alcohol unspecified

Table 22.

Plants and fungi

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mold | 26 (34.7) |

| Mushroom unspecified | 12 (16.0) |

| Mushroom (Psilocybe spp.) | 6 (8.0) |

| Miscellaneousa | 31 (41.3) |

| Class total | 75 (100) |

aIncludes Nerium oleander, Datura stramonium, Dieffenbachia, Kombucha tea, Mitragyna speciosa (kratom), mycotoxins, Amanita muscaria, Chrysanthemum parthenium, Cucurita pepo, Gyromitra, lavender, Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice), marigold, Morinda officinalis (Ba Ji Tian), Phytolacca (pokeweed), plants or fungi unspecified, solanines, toxalbumins, valerian root, dandelion, primrose, and Scutellaria (skullcap)

Table 23.

Metals

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Lead | 37 (25.5) |

| Iron | 22 (15.2) |

| Cobalt | 17 (11.7) |

| Chromium | 14 (9.7) |

| Mercury | 13 (9.0) |

| Arsenic | 6 (4.1) |

| Copper | 6 (4.1) |

| Miscellaneousa | 30 (20.7) |

| Class total | 145 (100) |

aIncludes gadolinium, manganese, magnesium, selenium, titanium, aluminum, metal unspecified, silver, antimony, beryllium, cadmium, cesium, thallium, uranium, and zinc sulfate

Table 24.

Gases, irritants, vapors, and dusts

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Carbon monoxide | 81 (58.7) |

| Cyanide | 10 (7.2) |

| Hydrogen sulfide | 7 (5.1) |

| Smoke | 7 (5.1) |

| Unspecified gas | 6 (4.3) |

| Sulfur dioxide | 5 (3.6) |

| Miscellaneousa | 22 (15.9) |

| Class total | 138 (100) |

aIncludes dust, asbestos, carbon disulfide, chlorine, nitrogen oxides, petroleum vapors, arsine, carbon dioxide, chloramine, phosgene, phosphine, polyurethane vapors, radon, and silica

Table 25.

Household products

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sodium hypochlorite ≤6 % | 35 (28.0) |

| Detergent pods | 26 (20.8) |

| Cleaning solutions and disinfectants | 24 (19.2) |

| Soaps and detergents unspecified | 13 (10.4) |

| Household product unspecified | 11 (8.8) |

| Miscellaneousa | 16 (12.8) |

| Class total | 125 (100) |

aIncludes hair products, paints, ammonia <10 %, hand sanitizer unspecified, deodorants/antiperspirants, dishwasher detergent, and sunscreens

Non-opioid analgesic entries for 2014 are shown in Table 9. Acetaminophen exposures accounted for 11.5 % of all Registry cases in 2014 and were the most common analgesic exposure (64.6 % within class frequency). Non-salicylate NSAIDS made up 24.6 % of this category, with ibuprofen the most common (12.1 %). Salicylates made up 27.0 % of the cases, primarily involving aspirin (16.9 %).

Sedative-hypnotic agents and muscle relaxants accounted for 12.4 % of all the agents reported (Table 8). As summarized in Table 10, benzodiazepines at 54.5 % accounted for the majority of the class as a whole, followed by muscle relaxants (20.7 %), other sedatives (17.4 %), nonbenzodiazepine agonists (8.9 %), and barbiturates (3.4 %). The two most common benzodiazepines, clonazepam (20.7 %) and alprazolam (15.1 %), accounted for over one third of the class. At least one benzodiazepine was reported in 9.1 % of all Registry cases. Zolpidem was the most common nonbenzodiazepine agent reported in this overall class (8.2 %), followed closely by the muscle relaxant cyclobenzaprine (7.5 %) and sedative gabapentin (7.4 %).

Table 11 summarizes the class of opioids, a category including natural opiates, semisynthetic and synthetic opioid agents. In 2014, 1311 individual opioid agents were reported, just over 10 % of all agents (Table 8). As in previous years, semisynthetic agents (heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, buprenorphine, hydromorphine, and oxymorphone) were the most common class subset at 63.3 % of all opioid entries. Heroin was the most common semisynthetic agent, at 26.7 %. Oxycodone was also relatively common, at 18.6 % of the class. The synthetic opioids (methadone, tramadol, fentanyl, naltrexone, loperamide, and naloxone) accounted for 25.7 % of the overall class, primarily due to methadone, tramadol, and fentanyl. The most common synthetic was methadone (12.1 %). The opiates morphine and codeine accounted for 5.7 % of the class.

Antidepressants accounted for 10.4 % of the total agents reported in the Registry (Table 8). As shown in Table 12, the two most common individual antidepressants reported were bupropion (17.7 %) and trazodone (13.8 % class). By comparison, the tricyclic antidepressants combined (13.5 %) appeared at a considerable lower frequency. Over one third of the antidepressants reported were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The most common SSRI, citalopram, accounted for 10.4 % of the antidepressant agents reported.

Table 8 shows that 6.1 % of all agents reported in 2014 were anticholinergic/antihistamine agents. As seen in Table 13, diphenhydramine was the most common individual agent, equaling 53.4 % of all reported agents in this class, followed by hydroxyzine (14.5 %), then three agents accounting for 5–6 % of the class (doxylamine, chlorpheniramine, and benzotropine). Of note, hydroxyzine was represented in 4.4 % of all Registry cases.

As listed in Table 14, the most common groups of cardiovascular agents were beta blockers (27.5 %), sympatholytics (22.4 %), and calcium channel antagonists (15.0 %). Metoprolol and propranolol were the two most common beta blockers, accounting for 10.7 and 6.9 %, respectively. Clonidine was the most commonly reported sympatholytic, responsible for 18.2 % of all cardiovascular agents, while amlodipine was the most common calcium channel antagonist (7.4 %). Clonidine was reported in 1.4 % of all Registry cases. Digoxin was the predominate cardiac glycoside (69 of 70 cases). Ace inhibitors, diuretics, antidysrhythmics, and other antihypertensives and vasodilators appeared to a much lesser extent. However, lisinopril, the most common ACE inhibitor, accounted for 7.4 % of the cardiovascular class.

Antipsychotics contributed 5.5 % of all agent entries to the Registry (Table 8). Atypical antipsychotics represented over 83 % of the class, primarily due to quetiapine (48.0 %), risperidone (11.6 %), aripiprazole (11.0 %), and olanzapine (10.6 %) (Table 15). Quetiapine exposure was represented in 6.3 % of the Registry cases. Within the overall class, an array of “first-generation” phenothiazines resulted in 3.5 % of agent entries.

Table 16 shows agents reported as sympathomimetics, including a range of pharmaceuticals, illicit drugs, and other designer stimulants associated with toxic exposures/consultations. Overall, this class contributed 5.5 % of all agent entries in 2014 (Table 8). At 37.1 %, cocaine was the majority contributor to this class, followed by methamphetamine and amphetamine, which combined accounted for another 32.6 %. Pharmaceutical stimulants of interest, such as those for treating attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, contributed for 2 % or more to this class. These drugs included methylphenidate (7.4 %), dextroamphetamine (4.9 %), and lisdexamfetamine (2.6 %). The most common designer amphetamine reported was methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine at 3.8 % of the class. A range of other designer stimulants were reported in smaller numbers, including 4-iodo-2,5-dimethoxy-N-(2-methoxybenzyl) phenethylamine (25I-NBOMe), cathinone, methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA), and alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone.

Anticonvulsants comprised 3.4 % of the agent entries, primarily due to valproic acid (27.6 %) and lamotrigine (22.3 %) (Table 17). The mood stabilizer lithium constitutes a single agent class in the Registry. In 2014, 179 occurrences, representing 2.0 % of the Registry cases, were entered.

Cases classified as involving other psychoactive drugs of abuse are shown in Table 18. Marijuana was the most frequent entry in this category in 2014, representing 32.4 % of all entries in this group. Synthetic cannabinoids, such as those referred to as “spice” or “K2,” were reported in 26.0 % of all class entries. Other psychoactive compounds included phencyclidine, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB).

Among envenomations and marine poisonings, over 70 % were related to Crotalus spp. (rattlesnake), Agkistrodon spp. (water moccasin), or snake species unspecified (Table 19); 17.7 % of envenomations were attributed to Loxsocoles spp. (recluse spider), Latrodectus spp. (widow spider), and Centruroides spp. (bark scorpions).

Antidiabetic medications metformin (29.5 %), insulin (24.3 %), glipizide (18.6 %), and glyburide (15.7 %) were responsible for the majority of entries among the diabetes-related medications reported (Table 20). Dextromethorphan accounted for 87.0 % of cough and cold product entries (see Supplementary Material).

Nine additional classes comprised the remaining pharmaceutical group classifications, accounting for 0.1–0.9 % of all agent entries (Table 8). A large number of individual agents contributed to the 69 antibiotics, 21 antivirals, antifungals, and other types of antimicrobials (both pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical uses). Warfarin accounted for 71.2 % of the anticoagulants, followed by rivaroxaban (10.6 %), with a variety of other agents in the class accounting for a limited number of entries (see Supplementary Material). For the remaining drug classes, the most common agents were the following: levothyroxine (endocrine agents), hydrogen peroxide and pyridostigmine (other pharmaceuticals), benzonatate (anesthetics), omeprazole (gastrointestinal), levodopa/carbodopa (anti-parkinsonism), theophylline (pulmonary), and hydroxychloroquine (chemotherapeutic and immunological).

Alcohols were classified into two categories, ethanol and other toxic alcohols (Table 21). As a single agent class, ethanol was responsible for 6.8 % of all agents. Table 21 summarizes case numbers for the other, less common toxic alcohols including ethylene glycol, isopropanol, methanol, and acetone, which as a group accounted for 0.8 % of the agent entries.

The agent class herbals and dietary supplements captured a broad range of products from a variety of sources (herbal, mineral, or chemical). Three single agents were responsible for 64.1 % of the 159 entries: caffeine, melatonin, and multivitamins. Over 30 other agents were responsible for the remaining 35.9 %. Table 22 shows a similar situation for the plant and fungi class, and mold (unspecified) was the most common agent class entry (34.7 %), followed by mushroom unspecified (16.0 %) and mushroom, Psilocybe spp. (8.0 %), with 22 other specific agents accounting for the remaining 41.3 % (31 cases) (data in Supplementary Materials).

Eight classes of agents were most often reported in occupational and environmental exposures: metals, hydrocarbons, pesticides, gases, caustics, irritants, vapors, and dusts. In the metal class, lead, iron, and cobalt accounted for over one half of the class entries (51.7 %), followed by chromium, mercury, arsenic, and copper (Table 23). Carbon monoxide was the most common entry in the gases, irritants, vapors, and dust class (Table 24). A large fraction of the entries for the hydrocarbon class were unspecified (38.1 %); toluene and gasoline were the only specific agents with five or more reported cases. Brodifacoum, a 4-hydroxycoumarin vitamin K antagonist (anticoagulant) poison, was the most common rodenticide entry (23 cases). Only a limited number of herbicides and fungicides were reported (total n = 6), with no agent with more than 2 entries. Organophosphates accounted for the majority of insecticide cases as indicated by entries for malathion, acephate, chlorpyrifos, and organophosphates unspecified, with several entries related to pyrethroids (permethrin, cypermethrin, pyrethrin unspecified). The caustic agent class also captured a broad range of agents, with only three individual agents with more than 5 occurrences (sodium hydroxide, hydrofluoric and hydrochloric acid), that combine to represent 36.3 % of the class entries (see Supplementary Material).

Additional non-pharmaceutical agents are included across four classes: household products, caustics, other nonpharmaceuticals, and ingested foreign objects (Table 25 and Supplementary Material). Other than sodium hypochlorite < 6 % in concentration (28 % of class), the majority of agent entries are chemically nonspecific as compared to the pharmaceuticals; however, these agents were still associated with 1.0 % of all agent entries (Table 8). In the class other non-pharmaceuticals, only “unspecified” agents had more than 3 entries, while batteries were the most commonly reported ingested foreign object.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

At least one clinical sign or symptom was reported in 7512 (81.9 %) cases. These findings are summarized in Tables 26, 27, 28, 29, and 30, organized by either syndrome or organ system. Sedative-hypnotic and anticholinergic were the two most common toxidromes reported (both reported in over 5 % of all cases), followed by opioid, sympathomimetic, and serotonin syndrome (Table 26). Tachycardia was the most common major vital sign abnormality (9.9 % cases) followed by hypotension (5.7 % cases) and bradycardia (3.5 % cases) (Table 27). Neurological effects were encountered most frequently among all signs and symptoms. Coma or CNS depression was observed in 2641 (28.8 %) cases (Table 28). Delirium, agitation, and rigidity/dystonia were relatively common as well, appearing in 10.7, 10.2, and 7.3 % of cases, respectively. Among pulmonary signs or symptoms, respiratory depression occurred most frequently (6.5 %), while prolonged QTc (>500 ms) or QRS (>120 ms) was the frequently reported cardiovascular effect (Table 29). All other individual signs or symptoms were reported in less than 6 % of Registry cases (Table 30).

Table 26.

Toxidromes

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Sedative-hypnotic | 631 (6.9) |

| Anticholinergic | 467 (5.1) |

| Opioid | 330 (3.6) |

| Sympathomimetic | 232 (2.5) |

| Serotonin syndrome | 210 (2.3) |

| Sympatholytic | 36 (0.4) |

| Alcoholic ketoacidosis | 26 (0.3) |

| NMS | 15 (0.2) |

| Washout syndrome | 11 (0.1) |

| Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity | 8 (0.1) |

| Overlap syndromes | 7 (0.1) |

| Cholinergic | 5 (0.05) |

| Fume fever | <5 (<0.05) |

| Total | 1980 (21.6) |

NMS neuroleptic malignant syndrome

aPercentage equals the number of cases reporting specific treatment relative to the total number of Registry cases in 2014 (N = 9172)

Table 27.

Major vital sign abnormalities

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Tachycardia (HR > 140) | 910 (9.9) |

| Hypotension (systolic BP < 80 mmHg) | 525 (5.7) |

| Bradycardia (HR < 50) | 319 (3.5) |

| Hypertension (systolic BP > 200 mmHg or diastolic BP > 120 mmHg) | 182 (2.0) |

| Bradypnea (RR < 10) | 149 (1.6) |

| Hyperthermia (temp > 105 °F) | 37 (0.4) |

| Total | 1733 (18.9)a,b |

HR heart rate, BP blood pressure

aPercentage equals the number of cases relative to the total number of Registry cases in 2014 (N = 9172)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one major vital sign abnormality. Cases may be associated with more than one major vital sign abnormality

Table 28.

Clinical signs and symptoms—neurological

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Coma/CNS depression | 2641 (28.8) |

| Delirium | 979 (10.7) |

| Agitation | 937 (10.2) |

| Hyperreflexia/myoclonus/tremor | 667 (7.3) |

| Seizures | 405 (4.4) |

| Hallucinations | 276 (3.0) |

| Dystonia/rigidity/extrapyramidal symptoms | 164 (1.8) |

| Weakness/paralysis | 97 (1.1) |

| Numbness/paresthesia | 74 (0.8) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 31 (0.3) |

| Total | 4500 (49.1)a,b |

CNS central nervous system

aPercentage equals the number of cases relative to the total number of Registry cases in 2014 (N = 9172)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one neurological symptom. Cases may be associated with more than one neurological symptom

Table 29.

Clinical signs—cardiovascular and pulmonary

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | |

| Prolonged QTc (≥500 ms) | 265 (2.9) |

| Prolonged QRS (≥120 ms) | 127 (1.4) |

| Ventricular dysrhythmia | 69 (0.8) |

| AV block (>1st degree) | 39 (0.4) |

| Total | 417 (4.5)b |

| Pulmonary | |

| Respiratory depression | 598 (6.5) |

| Aspiration pneumonitis | 136 (1.5) |

| Acute lung injury/ARDS | 75 (0.8) |

| Asthma/reactive airway disease | 56 (0.6) |

| Total | 772 (8.4)b |

ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome

aPercentage equals the number of cases reporting specific treatment relative to the total number of Registry cases in 2014 (N = 9172)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one cardiovascular or pulmonary symptom. Cases may be associated with more than one symptom.

Table 30.

Clinical signs—other organ systems

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Metabolic | |

| Metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.2) | 323 (3.5) |

| Elevated anion gap (>20) | 276 (3.0) |

| Hypoglycemia (glucose < 50 mg/dL) | 182 (2.0) |

| Elevated osmole gap (>20) | 40 (0.4) |

| Total | 624 (6.8)b |

| Gastrointestinal/hepatic | |

| Hepatotoxicity (AST ≥ 1000 IU/L) | 316 (3.4) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 48 (0.5) |

| Corrosive injury | 35 (0.4) |

| Pancreatitis | 31 (0.3) |

| Intestinal ischemia | 8 (0.1) |

| Total | 409 (4.5)b |

| Hematological | |

| Coagulopathy (PT > 15 s) | 179 (2.0) |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelets < 100 K/μL) | 75 (0.8) |

| Leukocytosis (WBC > 20 K/μL) | 65 (0.7) |

| Hemolysis (Hgb < 10 g/dL) | 23 (0.3) |

| Methemoglobinemia (MetHgb ≥ 2 %) | 13 (0.1) |

| Pancytopenia | 13 (0.1) |

| Coagulopathy (PT > 15 s) | 179 (2.0) |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelets < 100 K/μL) | 75 (0.8) |

| Total | 306 (3.3)b |

| Renal/musculoskeletal | |

| Acute kidney injury (creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL) | 346 (3.8) |

| Rhabdomyolysis (CPK > 1000 IU/L) | 317 (3.5) |

| Total | 573 (6.2)b |

| Dermatological | |

| Rash | 122 (1.3) |

| Blister/bullae | 76 (0.8) |

| Necrosis | 22 (0.2) |

| Angioedema | 14 (0.2) |

| Total | 199 (2.2)b |

PT prothrombin time, WBC white blood cells, Hgb hemoglobin, CPK creatinine phosphokinase

aPercentage equals the number of cases reporting specific treatment relative to the total number of Registry cases in 2014 (N = 9172)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one symptom in the category. Cases may be associated with more than one symptom

Fatalities

There were 89 fatalities reported in the Registry in 2014, comprising 0.97 % of all cases (Tables 31 and 32, Supplementary Material). Forty-eight (53.4 %) of these cases were female. The average age of fatalities was 45.1 years, ranging from 8 weeks to 80 years of age. As in 2013, nonopioid analgesics and opioids were the most frequently reported agents among these cases. For cases reporting a single agent poisoning (38 cases or 42.7 % of all fatalities), acetaminophen was the agent reported for all 12 analgesic-related events. One half of the six opioid-related deaths were related to heroin, with the remainder of single agent opioid-related events due to methadone, oxycodone, and tramadol.

Table 31.

2014 fatalities reported in toxic registry with known toxicological exposure: single agent

| Age/gendera | Agents involved | Clinical findings | Life support withdrawn | Brain death confirmed | Treatmentb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 F | Propofol | HT, TC, BP, AGT, AG, AKI, RBM | Yes | Unknown | Carnitine |

| 14 M | Oxycodone | HT, VD, RD, CNS | Yes | Unknown | Naloxone |

| 19 F | Methanol | HT, VD, ALI, CNS, SZ, MA, AG | No | Unknown | Folate, fomepizole, pyridoxine, NaHCO3, thiamine, vasopressors, anticonvulsants, steroids, hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 21 F | Acetaminophen | HT, CNS, MA, HPT, GIB, HYS, CPT, PLT, AKI | Yes | Unknown | Factor replacement, NAC, vitamin K, vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia, transfusion |

| 23 F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, CNS, DLM, HGY, MA, CPT, WBC, AKI | No | Unknown | Fomepizole, NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, glucose, neuromuscular blockers, steroids, hemodialysis, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 24 F | Acetaminophen | CNS, HGY, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, AKI, RBM | Yes | Yes | NAC, vasopressors, glucose, intubation, IV fluids |

| 25 M | Sodium hydroxide | HT, TC, AP, CRV, PLT, WBC | Yes | No | None listed |

| 27 M | Heroin | BP, RD, CNS | Yes | No | Vasopressors, CPR, intubation |

| 29 F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, AKI, | Yes | No | NAC, vasopressors, |

| 31 F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, VD, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, HYS, CPT, WBC, AKI | Yes | No | NAC, NaHCO3, vitamin K, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, continuous renal replacement, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 34 F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, RD, CNS, DLM, RFX, HGY, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, PLT, WBC, AKI | Yes | No | NAC, vasopressors, bronchodilators, benzodiazepines, glucose, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, intubation |

| 36 M | Ethanol | HT, CNS, HGY, MA, AG, HPT, GIB, CPT, AKI | No | Unknown | Fomepizole, NAC, NaHCO3, thiamine, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, glucose, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 40 M | Ibogaine | None listed | Yes | Yes | None listed |

| 41 F | Acetaminophen | HPT, PLT | No | Unknown | NAC |

| 44 M | Methamphetamine | HT, TC, RD, CNS, MA, AG, PNC, WBC, PLT, AKI, RBM | No | Unknown | Fomepizole, benzodiazepines, glucose, intubation, IV fluids |

| 46 F | Acetaminophen | CNS, HGY, HPT, CPT, AKI | No | Unknown | NAC, IV fluids, pacemaker, transplantation |

| 47 M | Heroin | HT, CNS, RBM | Missing | Missing | Naloxone |

| 47 M | Insulin | CNS, HGY | Yes | Yes | Octreotide, glucose, intubation |

| 48 F | Acetaminophen | CNS, DLM, MA, HPT, PNC, CPT, WBC, AKI | Yes | Unknown | NAC, thiamine, hemodialysis |

| 48 F | Heroin | QTc, RD, AGT, MA, PNC, HYS, CPT | No | Unknown | Naloxone, opioids, intubation |

| 49 M | Phenytoin | CNS, HPT | Yes | Unknown | None listed |

| 52 F | Acetaminophen | RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, CPT | Yes | No | Flumazenil, NAC, naloxone, vasopressors |

| 56 F | Tramadol | HT, VD, SZ, MA, WBC, AKI | Unknown | Unknown | Atropine, vasopressors, intubation |

| 57 F | Methadone | HT, BP, AP, RD, CNS, DLM, WKN, PLT | Yes | No | Flumazenil, naloxone, bronchodilators, benzodiazepines, opioids, intubation |

| 59 M | Verapamil | HT, BC, AKI | Yes | No | Lipid resuscitation, IV fluids |

| 60 M | Amlodipine | HT, ALI, RD, CNS, MA, AKI | No | Unknown | Calcium, glucagon, insulin-euglycemic therapy, vasopressors, glucose, intubation, IV fluids |

| 62 M | Ethylene glycol | None listed | Yes | No | Fomepizole |

| 63 M | Metformin | TC, CNS, MA, HPT, AKI | Yes | Yes | Vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluids |

| 66 M | Ethanol | HT, TC, AP, ALI, CNS, HGY, MA, AG, GIB, INT, PLT, PCT, AKI | Yes | No | Folate, fomepizole, NaHCO3, thiamine, hemodialysis, IV fluids |

| 67 F | Ethylene glycol | HT, BC, AP, ALI, CNS, MA, AG | No | Unknown | Fomepizole, NaHCO3, vasopressors, glucose |

| 68 M | Temazepam | HT, ALI, CNS | Yes | Yes | Naloxone, vasopressors, intubation |

| 71 M | Insulin | HGY | No | Unknown | Glucose |

| 75 F | Acetaminophen | ALI, RD, CNS, WBC, AKI | No | No | None listed |

| 77 F | Acetaminophen | HT, CNS, MA, HPT | Yes | Yes | NAC, vasopressors |

| 78 F | Digoxin | HT, VD, RD, CNS | Yes | Yes | Digoxin Fab, vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, CPR, cardioversion |

| 78 M | Smoke | HT, ALI | Unknown | Unknown | Thiosulfate |

| 83 F | Digoxin | BC, CNS, HGY, MA, AG, AKI | No | Unknown | Atropine, digoxin Fab |

| 86 F | Warfarin | CPT | Yes | Yes | Anticoagulant reversal |

Based on the response from a medical toxicologist “Did the patient have a toxicological exposure?” equals Yes with known agent(s)

AG anion gap, AGT agitation, AKI acute kidney injury, ALI acute lung injury/ARDS, AP aspiration pneumonia, AVB AV block, BC bradycardia, BP bradypnea, CNS: Coma/CNS depression, CPT coagulopathy, CRV corrosive injury, DLM delirium, EPS dystonia, GIB GI bleeding, HCN hallucinations, HGY hypoglycemia, HPT: Hepatoxicity, HT hypotension, HTN hypertension, HYS hemolysis, HYT hyperthermia, INT intestinal ischemia, MA metabolic acidosis, MET methemoglobinemia, NP neuropathy, OG osmole gap, PCT pancytopenia, PLT thrombocytopenia, PNC pancreatitis, PST paresthesia, QRS QRS prolongation, QTc QTc prolongation, RAD asthma/reactive airway disease, RBM rhabdomyolysis, RD respiratory depression, RFX hyperreflexia/tremor, SZ seizures, TC tachycardia, VD ventricular dysrhythmia, WBC leukocytosis, WKN weakness/paralysis, CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, NAC N-acetylcysteine, NaHCO 3 sodium bicarbonate

aAge in years unless otherwise stated

bPharmacological and nonpharmacological support as reported by a medical toxicologist

Table 32.

2014 fatalities reported in toxic registry with known toxicological exposure: multiple agents

| Age/gendera | Agents involved | Clinical findings | Life Support Withdrawn | Brain Death Confirmed | Treatmentb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks F | Atorvastatin, omega-3-acid ethyl esters | HT, TC, RD, CNS, MA, HPT, HYS, CPT, PLT | Yes | No | Intubation |

| 14 months M | Amphetamine, dextroamphetamine | TC, AGT, RFX | Yes | Benzodiazepines | |

| 14 M | Metformin, clonidine, quetiapine, valproic acid | HT, TC, CNS, MA | No | Unknown | Lipid resuscitation, gastric lavage, charcoal, CPR, cardioversion, IV fluids |

| 14 M | Heroin, cocaine | CNS | Unknown | Unknown | Naloxone |

| 16 M | Methadone, alprazolam | HT, BC, VD, QTc, | Yes | Unknown | Vasopressors, antiarrhythmics |

| 21 M | Acetaminophen, aripiprazole, melatonin | HPT | Yes | No | NAC, IV fluids |

| 23 F | Diphenhydramine, methamphetamine | VD, QRS, DLM | No | Unknown | NaHCO3, intubation, IV fluids |

| 23 M | Bupropion, citalopram | HT, CNS | Yes | Yes | Lipid resuscitation, vasopressors, intubation |

| 25 F | Oxycodone, methadone, carisoprodol, alprazolam | HT, BC, ALI, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, PLT, AKI, RBM | Yes | Unknown | NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, glucose, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 29 F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, AKI, | Yes | No | NAC, vasopressors |

| 29 F | Cocaine, carbon monoxide | RD, CNS, MA | Yes | Yes | None listed |

| 31 F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, VD, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, HYS, CPT, WBC, AKI | Yes | No | NAC, NaHCO3, vitamin K, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, continuous renal replacement, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 31 F | Smoke, cyanide, carbon monoxide | HT, VD | Yes | Yes | Hydroxocobalamin, hyperbaric O2 |

| 31 M | Heroin, doxylamine | SZ | Yes | No | Benzodiazepines, intubation |

| 32 F | Quetiapine, oxycodone, heroin, methamphetamine | HT, BC, BP, VD, QTc, QRS, ALI, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HYS, AKI, RBM | Yes | Yes | Lipid resuscitation, NAC, naloxone, NaHCO3, vasopressors, charcoal, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 32 M | Acetaminophen, brodifacoum, aspirin | HT, CNS, RFX, HPT, PNC, CPT, AKI, PLT | Yes | Yes | NAC, vitamin K, vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 35 M | Cyclobenzaprine, hydroxyzine | HT, BC, ALI, CNS, MA | Yes | Unknown | Calcium, NAC, NaHCO3, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, pacemaker |

| 43 F | Propranolol, tizanidine, metformin | HT, RD, CNS, AKI | Yes | No | Insulin-euglycemic therapy, NAC, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, intubation, IV fluids |

| 44 F | Acetaminophen, aspirin | RD, CNS, HPT, AKI | Yes | Yes | NAC, naloxone, NaHCO3, vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 45 M | Clonazepam, methadone, gabapentin | HT, TC, BC, RD, CNS | No | Unknown | Vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 48 M | Verapamil, carvedilol, levetiracetam, lisinopril, atazanavir | BC, RD, CNS, AG, AKI | Unknown | Unknown | Atropine, glucagon, lipid resuscitation, vasopressors, CPR, IV fluids |

| 51 M | Acetaminophen, ethanol | HT, TC, HGY, MA, AG, HPT, PNC, GIB, WBC, PLT, AKI | Unknown | Unknown | NAC, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 52 F | Metoprolol, amlodipine | HT, BC, VD, CNS | No | Unknown | Atropine, insulin-euglycemic therapy, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, glucose, CPR, cardioversion, intubation, IV fluids, pacemaker |

| 54 F | Fentanyl, oxycodone | None listed | Unknown | Unknown | Naloxone, bronchodilators, steroids, |

| 55 F | Propofol, hydromorphone, midazolam, quetiapine, fluoxetine | HTN, ALI, AGT, CNS | Unknown | Unknown | Flumazenil, naloxone, physostigmine |

| 56 F | Hydroxychloroquine, hydrocodone, acetaminophen, clonazepam, levodopa/carbidopa | HT, CNS | Yes | Unknown | NAC |

| 65 F | Propafenone, clonazepam | None listed | Unknown | Unknown | None listed |

| 71 M | Oxycodone, acetaminophen | AP, RD, CNS, MA, AG, AKI | Yes | No | NAC, NaHCO3, intubation, IV fluids |

| 76 F | Acetaminophen, butalbital | HT, TC, QTc, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, GIB, CPT, WBC, RBM | Yes | No | Naloxone, vasopressors, glucose |

| 78 F | Rivaroxaban, clopidogrel | CNS | Yes | No | Factor replacement, bronchodilators, benzodiazepines, opioids, intubation, IV fluids |

| 79 M | Digoxin, atenolol, carvedilol, furosemide | HT, BC, VD, MA, AKI | No | Yes | Digoxin Fab, vasopressors |

Based on the response from a MEDICAL Toxicologist “Did the patient have a toxicological exposure?” equals Yes with known agent(s)

AG anion gap, AGT agitation, AKI acute kidney injury, ALI acute lung injury/ARDS, AP aspiration pneumonia, AVB AV block, BC bradycardia, BP bradypnea, CNS coma/CNS depression, CPT coagulopathy, CRV corrosive injury, DLM delirium, EPS dystonia, GIB GI bleeding, HCN hallucinations, HGY hypoglycemia, HPT hepatoxicity, HT hypotension, HTN hypertension, HYS hemolysis, HYT hyperthermia, INT intestinal ischemia, MA metabolic acidosis, MET methemoglobinemia, NP neuropathy, OG osmole gap, PCT pancytopenia, PLT thrombocytopenia, PNC pancreatitis, PST paresthesia, QRS QRS prolongation, QTc QTc prolongation, RAD asthma/reactive airway disease, RBM rhabdomyolysis, RD respiratory depression, RFX hyperreflexia/tremor, SZ seizures, TC tachycardia, VD ventricular dysrhythmia, WBC leukocytosis, WKN weakness/paralysis, CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, NAC N-acetylcysteine, NaHCO 3 sodium bicarbonate

aAge in years unless otherwise stated

bPharmacological and nonpharmacological support as reported by a medical toxicologist

Among the 31 multiple agent fatalities (34.8 % of the total), 10 cases involved one or more opioids: oxycodone (4 cases), methadone (3 cases), and heroin (3 cases). Non-opioid analgesics were reported in seven multiple agent poisonings (primarily acetaminophen, nine cases).

In a substantial portion of cases, 22 of 89 (24.7 %), no agent was entered into the ToxIC Registry (see Supplementary Material). For the majority of this subset, 19 of 22 cases (86.4 % with no agent), the consulting/attending medical toxicologist determined that the patient did not have a toxicological exposure (7 cases), or it was unclear/unknown (12 cases); therefore, no agent information was entered. In the remaining three cases, the data was either missing or coded as “unknown agent” by the clinician.

In 57 cases (64 %), life support was withdrawn; among this latter subset, actual brain death was confirmed in 24 cases (42.1 %).

Adverse Drug Reactions

In 2014, 410 Registry cases (4.5 %) reported the involvement of an adverse drug reaction (ADR). During 2014, Registry data fields were expanded to include a separate field to identify ADRs from among the reasons for a toxicological consultation. A total of 194 drugs or substances were mentioned at least once with the aid of this additional indicator field. Table 33 lists the 16 most frequently encountered drugs associated with ADRs (single and multiple drug exposure). The overall findings are similar to the ADR summary from the 2013 Registry report [5]. Lithium remains the most frequently cited drug associated with ADRs. Likewise, the most frequently encountered agent classes (non-opioid analgesics, sedative-hypnotics, opioids) are relatively underrepresented in Table 33, with psychiatric medications (antipsychotics 14.6 %, antidepressants 19.3 %) and cardiovascular medications (17.6 %) cited more frequently. The relative pattern changes somewhat if only single drug exposure events are considered (259 or 63.2 % of all ADRs). Lithium (13.5 %), digoxin (9.3 %), and phenytoin and valproic acid (both <5 %) are the four most common individual medications, with cardiovascular (15.8 %), lithium (13.5 %), anticonvulsants (10.8 %), and antipsychotics (8.9 %) as the most common classes.

Table 33.

Most common drugs associated with ADRs

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Lithium | 45 (11.0) |

| Digoxin | 29 (7.1) |

| Valproic acid | 16 (3.9) |

| Phenytoin | 14 (3.4) |

| Quetiapine | 12 (2.9) |

| Citalopram | 11 (2.7) |

| Tramadol | 11 (2.7) |

| Bupropion | 10 (2.4) |

| Risperidone | 10 (2.4) |

| Trazodone | 10 (2.4) |

| Aripiprazole | 8 (2.0) |

| Fentanyl | 8 (2.0) |

| Glipizide | 8 (2.0) |

| Methadone | 8 (2.0) |

| Metoprolol | 8 (2.0) |

| Sertraline | 8 (2.0) |

| Total | 216 (36.4) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of all drugs reported involved in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); 410 ADRs, with 593 individual agents; 4.5 % of registry cases in 2014 reported as a ADR

Treatment

Specific treatment was rendered in 62.3 %, with 5715 Registry cases reporting more than one treatment modality. There were a total of 2962 instances of antidote administration, accounting for 51.8 % of all treatments reported; 4.2 % of all Registry cases received more than one antidotal therapy for a given event. N-acetylcysteine and naloxone/nalmefene collectively comprised over half of all antidotal treatment (Table 34). With the exception of sodium bicarbonate, all other antidotes were used relatively infrequently, with each individual drug accounting for less than 10 % of antidote administrations. Antivenom usage was uncommon, being given in only 197 (2.1 %) of all Registry cases, with polyvalent anti-Crotalidae Fab accounting for a large majority of antivenom treatments (93.4 %) (Table 35).

Table 34.

Antidotal therapy

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| N-acetylcysteine | 921 (31.1) |

| Naloxone/nalmefene | 605 (20.4) |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 322 (10.9) |

| Physostigmine | 156 (5.3) |

| Thiamine | 119 (4.0) |

| Fomepizole | 90 (3.0) |

| Flumazenil | 81 (2.7) |

| Glucagon | 80 (2.7) |

| Calcium | 77 (2.6) |

| Folate | 74 (2.5) |

| Octreotide | 67 (2.3) |

| Atropine | 51 (1.7) |

| Cyproheptadine | 49 (1.7) |

| Vitamin K | 45 (1.5) |

| Insulin-euglycemic therapy | 41 (1.4) |

| l-Carnitine | 38 (1.3) |

| Fab for digoxin | 35 (1.2) |

| Lipid resuscitation | 33 (1.1) |

| Pyridoxine | 17 (0.6) |

| Bromocriptine | 12 (0.4) |

| Dantrolene | 11 (0.4) |

| Hydroxocobalamin | 11 (0.4) |

| 2-PAM | 7 (0.2) |

| Anticoagulant reversal therapy | 4 (0.1) |

| Thiosulfate | 4 (0.1) |

| Ethanol | 3 (0.1) |

| Coagulation factor replacement | 3 (0.1) |

| Methylene blue | 3 (0.1) |

| Nitrites | 3 (0.1) |

| Total | 2962 (100) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of antidotes administered (2962); 4.2 % of registry cases received more than one antidote

Table 35.

Antivenom therapy

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Polyvalent anti-Crotalidae Fab fragments | 184 (93.4) |

| Spider antivenom | 6 (3.0) |

| Other snake antivenom | 4 (2.0) |

| Scorpion antivenom | 3 (1.5) |

| Total | 197 (100) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of antivenom treatments administered (197)

In the case of pharmacological support, 5.2 % of the Registry cases indicated that more than one form was used for the given toxic event (Table 36). Benzodiazepines and opioids were utilized most frequently, combining for approximately two thirds of all treatments rendered. There were 2867 nonpharmacological therapies given, with 5.8 % of cases receiving more than one treatment modality (Table 37). Intravenous fluid resuscitation and mechanical ventilation management accounted for a large majority of treatments, 67.6 and 27.8 %, respectively. The remaining non-pharmacological supportive care each accounted for less than 2 % of treatments rendered. Chelation was reported for only 21 Registry cases, with 2 receiving multiple chelation modalities. Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) accounted for 18 of the 23 chelation therapies reported (Table 38).

Table 36.

Supportive care—pharmacological

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | 1624 (7.1) |

| Opioids | 261 (9.2) |

| Vasopressors | 239 (8.4) |

| Antipsychotics | 186 (6.5) |

| Glucose (concentration > 5 %) | 165 (5.8) |

| Anticonvulsants | 78 (2.7) |

| Neuromuscular blockers | 66 (2.3) |

| Albuterol (or other bronchodilator) | 63 (2.2) |

| Corticosteroids | 49 (1.7) |

| Antiarrhythmics | 42 (1.5) |

| Antihypertensives | 35 (1.2) |

| Beta blockers | 27(0.9) |

| Vasodilators | 8 (0.3) |

| Total | 2843 (100) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of treatments administered (2843); 5.2 % of registry cases received more than one form of pharmacological treatment

Table 37.

Supportive care—non-pharmacological

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| IV fluid resuscitation | 1937 (67.6) |

| Intubation/ventilatory management | 796 (27.8) |

| CPR | 40 (1.4) |

| Hyperbaric oxygen | 21 (0.7) |

| Transfusion | 21 (0.7) |

| Pacemaker | 15 (0.5) |

| Therapeutic hypothermia | 13 (0.5) |

| Cardioversion | 11 (0.4) |

| ECMO | 7 (0.2) |

| Organ transplantation | 4 (0.1) |

| Aortic balloon pump | 1 (0.0) |

| Bypass | 1 (0.0) |

| Total | 2867 (100) |

CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECMO extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

aPercentages are out of the total number of treatments administered (2867); 5.8 % of registry cases received more than one form of nonpharmacological treatment

Table 38.

Chelation therapy

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| DMSA | 11 (47.8) |

| EDTA | 7 (30.4) |

| Dimercaprol (BAL) | 4 (17.4) |

| Deferoxamine | 1 (4.3) |

| Total | 23 (100) |

DMSA dimercaptosuccinic acid, EDTA ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid

aPercentages are out of the total number of chelation treatments administered (23)

There were 409 recorded decontamination therapies across 372 cases, indicating that 37 cases received multiple treatments (Table 39). Activated charcoal was the most frequently reported decontamination modality applied (79.5 %). There were 245 separate uses of enhanced elimination techniques, with only 0.3 % of all registry cases receiving multiple forms of enhanced elimination (Table 40). Renal replacement therapy, either hemodialysis or continuous renal replacement (e.g., CVVH), accounted for 70.6 % of enhanced elimination therapy.

Table 39.

Decontamination

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Activated charcoal | 325 (79.5) |

| Whole bowel irrigation | 46 (11.2) |

| Gastric lavage | 23 (5.6) |

| External irrigation | 15 (3.7) |

| Total | 409 (100) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of treatments administered (409); 37 registry cases received more than one form of decontamination

Table 40.

Enhanced elimination

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Hemodialysis (toxin removal) | 74 (30.2) |

| Urinary alkalinization | 56 (22.9) |

| Hemodialysis (other indication) | 50 (20.4) |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 49 (20.0) |

| Multiple-dose activation charcoal | 14 (5.7) |

| Exchange transfusion | 2 (0.8) |

| Total | 245 (100) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of treatments administered (245); 27 registry cases received more than one form of enhanced elimination

Discussion

This report of the ACMT ToxIC Registry serves as an overview of cases involving medical toxicology consultations reported in 2014. In its fifth year, the Registry continues to grow in both the number of reported cases and participating institutions (Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2). In 2014, many of the observed percentages of type of consultation, reason for consultation, as well as general agent class reported remain similar to those found in prior years [2–5]. Intentional pharmaceutical exposure remains the most frequent cause of consultations, with analgesics, sedative-hypnotic agents, opioids, and antidepressants continuing to constitute the most frequently encountered agent classes.

However, the rank order based on relative proportion of these classes has varied somewhat over the 5-year period. As the number of data years collected increase, the ability to observe real changes or trends will continue to improve. The degree to which this variability reflects an actual change in the affected populations’ exposure (or type of use) versus operational or other characteristic changes in the participating institutions cannot be determined from a single broad, descriptive review based on single variables. The Registry data can be used to identify more refined areas for hypothesis generation, and provide starting points for initiating additional observation or clinical research by specific type of encounter, agent, or treatment.