Abstract

Medication non-adherence is a common precipitant of heart failure (HF) hospitalization and is associated with poor outcomes. Recent analyses of national data focus on long-term medication adherence. Little is known about adherence of HF patients immediately following hospitalization. Hospitalized HF patients were identified from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. ARIC data were linked to Medicare inpatient and Part D claims from 2006–2009. Inclusion criteria were: a chart adjudicated diagnosis of acute decompensated or chronic HF; documentation of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB), beta-blocker (BB), or diuretic prescription at discharge; Medicare Part D coverage. Proportion ambulatory days covered (PADC) was calculated for up to twelve 30-day periods after discharge. Adherence was defined as ≥80% PADC. We identified 402 participants with Medicare Part D: mean age 75, 30% male, 41% black. Adherence at 1, 3 and 12 months was 70%, 61%, 53% for ACEI/ARB, 76%, 66%, 62% for BB, and 75%, 68%, 59% for diuretic. Adherence to any single drug class was positively correlated with being adherent to other classes. Adherence varied by geographic site/race for ACEI/ARB and BB but not diuretics. In conclusion, despite having Part D coverage, medication adherence post discharge for all three medication classes declined over 2–4 months after discharge, followed by a plateau over the subsequent year. Interventions should focus on early and sustained adherence.

Keywords: Heart failure, hospitalization, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor blocker, beta-blocker, medication adherence

Most studies of medication adherence in heart failure (HF) patients have focused on long-term adherence.1–8 Little is known about the temporal trend of medication adherence immediately after hospitalization in patients with documented discharge medications.9 Previous studies often required a filled prescription for study inclusion, which may overestimate adherence.2–7, 9 In the few studies that have utilized Medicare Part D data, adherence has been described in patients with either an inpatient or outpatient HF claim.4, 5, 7 However, no study using Medicare Part D data has examined adherence to HF-specific medications immediately after hospitalization. This issue is of significant policy interest since the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is now tying payment to readmission rates for some chronic diseases, including HF. These initiatives have led to increased emphasis on interventions to reduce readmissions.10, 11 Prior work has demonstrated improved rates of guideline-concordant medication prescribed at discharge, but we know relatively little about adherence and its determinants post-discharge. To determine whether medication adherence changes over time, we examined monthly medication adherence for angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB), beta-blocker (BB), and diuretic therapies for up to 1 year after hospitalization using Part D data available for participants of the Atherosclerosis Risk in the Communities (ARIC) study. We included ARIC participants who had an adjudicated diagnosis of hospitalized acute decompensated (ADHF) or chronic HF in 2006–2009 and documentation of discharge medications from chart abstraction.

Methods

The ARIC study is an on-going predominantly biracial cohort of 15,792 men and women from 4 US communities (Forsyth County, North Carolina; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Jackson, Mississippi; and Washington County, Maryland) and followed since 1987–89.12 The ARIC study began detailed abstraction of hospital discharge records for cohort members hospitalized with HF in 2005, as previously described.13 In brief, inclusion criteria for detailed abstraction included an International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnosis code for HF or a related condition or symptom (398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 415.0, 416.9, 425.4, 428.x, 518.4, 786.0x). Discharge diagnosis codes could be in any position for inclusion. Study participants’ hospitalization records were reviewed for evidence of signs and symptoms of HF, including new onset or worsening shortness of breath, peripheral edema, paroxysmal dyspnea, orthopnea, and hypoxia. In the presence of such evidence, a detailed abstraction of the medical record was completed. HF was classified as definite or possible ADHF or as chronic stable heart failure by independent physician reviewers. The ability to distinguish between ADHF and chronic stable HF is a strength of the ARIC study.

Data on participant demographics and hospitalizations came from the ARIC study. Validated hospitalizations for ADHF or chronic stable HF were identified and merged with Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) inpatient stay records, Medicare hospice claims, and Medicare Part D claims using unique ARIC study participant identifiers and information concerning dates of service. The MedPAR records were used to obtain information on days in skilled nursing facility and all-cause hospital admissions that were not abstracted. For this analysis, claims for Medicare Part D prescriptions were identified using National Drug Codes and examined by medication class. Since the ARIC study collects information on all hospitalizations through active surveillance, we were able to include Medicare Advantage enrollees as well as fee-for-service enrollees. To ensure capture of all Part D medication fills (e.g., 90 day fills), ARIC study participants were included in this retrospective analysis if they were enrolled in Medicare Part D at the time of discharge and for at least 3 months prior to hospitalization. Only the first HF hospitalization observed between April 2006 and December 2009 was used for each participant in order to depict adherence over a 12 month period and enable comparability of assessment to other studies looking at annual rates of adherence. Participant characteristics including comorbidities, history of HF hospitalization, blood pressure, heart rate, laboratory values, and discharge medications were abstracted from the chart. Assessments of left ventricular function and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were documented in the current or previously available medical records or in reports of cardiac imaging (echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, and nuclear or other cardiac imaging) available to ARIC.

The study population included 834 ARIC cohort participants who had a hospitalization for ADHF or chronic stable HF from April 2006 through December 2009. We excluded 5 participants who were Veterans and had no Part D claims filed for the three medications at any point during the study period. A total of 426 participants had documentation regarding medications prescribed at discharge, as well as Part D enrollment for at least 3 months prior to discharge. We excluded 24 participants who were not discharged on any of the three classes of medications. The final study sample was 402.

Prescriptions at discharge for ACEI/ARB, BB, or diuretic therapy were documented by chart abstraction. Proportion of ambulatory days covered (PADC) was determined using fill date and days supplied and was calculated as proportion of days the drug was available during the study period divided by the number of days the patient was not in a hospital, skilled nursing facility, or hospice. To account for switches within a class or changes in dose, PADC was not calculated in excess of 1 for any time period. The PADC was determined for up to twelve 30-day periods after hospital discharge for each medication; the 30-day periods are subsequently referred to as “months.” Medication adherence was defined as ≥80% PADC over the specified time period. Observations were censored by death or end of study period (12/31/2009); observations were only included in the calculation of adherence each month if the person had at least some days in an ambulatory setting (i.e., days not in a hospital, skilled nursing facility, or on the Medicare hospice benefit). Bivariate associations of medication adherence class over the first 3 months following discharge were assessed using chi-square tests (for dichotomous participant characteristics) or t-tests (continuous measures) for each drug. We examined the following participant characteristics from the hospitalization in relation to adherence: demographics, comorbidities, history of HF hospitalization, ADHF vs. chronic HF, heart failure type, LVEF, assessment of LVEF during hospitalization, blood pressure, heart rate, serum sodium, serum creatinine, length of stay, and adherence to the other two medication classes.

Results

Overall, we studied 402 ARIC cohort participants who were hospitalized for ADHF or chronic stable HF from April 2006 through December 2009, had medications documented at discharge and were enrolled in Part D for at least 3 months prior to discharge. Table 1 provides characteristics of the sample of 402 participants with documentation of at least one of three medication classes at discharge. Participants were 75 ± 6 years of age, 30% were men, and 40% were black. The majority of participants, 70%, were hospitalized for ADHF. Documentation of LVEF was available for 83% of the 402 participants either by assessment during hospitalization, from information available in ARIC study records for a previous hospitalization, or imaging studies prior to the study period. Based on available documentation, 55% of participants with an assessment of left ventricular function had an LVEF <50%. Table 2 shows the proportion of the 402 participants prescribed various combinations of the following three medication classes. In total, 62% (n = 248) were discharged on ACEI/ARB, 76% (n = 305) on BB, and 80% (n = 321) on a diuretic. Only 39% of participants were discharged on all three medication classes.

Table 1.

Sample Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (n=402)

| Characteristic | Mean (±SD) or % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 75.4 ± 5.6 | |

| Male | 30% | |

| ARIC geographic region and race | Washington County white | 18% |

| Forsyth County white | 21% | |

| Forsyth County black | 3% | |

| Minneapolis white | 21% | |

| Jackson black | 37% | |

| Hypertension | 87% | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 54% | |

| Lung Disease | 39% | |

| Myocardial infarction | 24% | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 26% | |

| Stroke/Transient Ischemic Attack | 20% | |

| Depression | 10% | |

| Dialysis | 6% | |

| Smoker | 12% | |

| Previous HF hospitalization | 42% | |

| Acute decompensated HF | 70% | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 145 ± 33 | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 87 ± 23 | |

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) | 136 ± 4.4 | |

| Serum blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 38 ± 23 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 2 ± 1.6 | |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/1.73m2) | 42 ± 21 | |

| LV assessment during hospitalization | 51% | |

| LVEF | 43% ± 17.4 | |

| LVEF ≤ 40% | 40% | |

| LVEF < 50% | 55% | |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 7.6 ± 15.5 |

HF = heart failure; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction.

LVEF was missing for 17% of cases.

Table 2.

Drug Prescriptions at Hospital Discharge

| Medication Classes (n=402) | |

|---|---|

| ACEI/ARB + BB + Diuretic | 155 (39%) |

| BB + Diuretic | 76 (19%) |

| Diuretic | 46 (11%) |

| ACEI/ARB + Diuretic | 44 (11%) |

| ACEI/ARB + BB | 42 (10%) |

| BB | 32 (8%) |

| ACEI/ARB | 27 (2%) |

ACEI/ARB = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; BB = beta blocker.

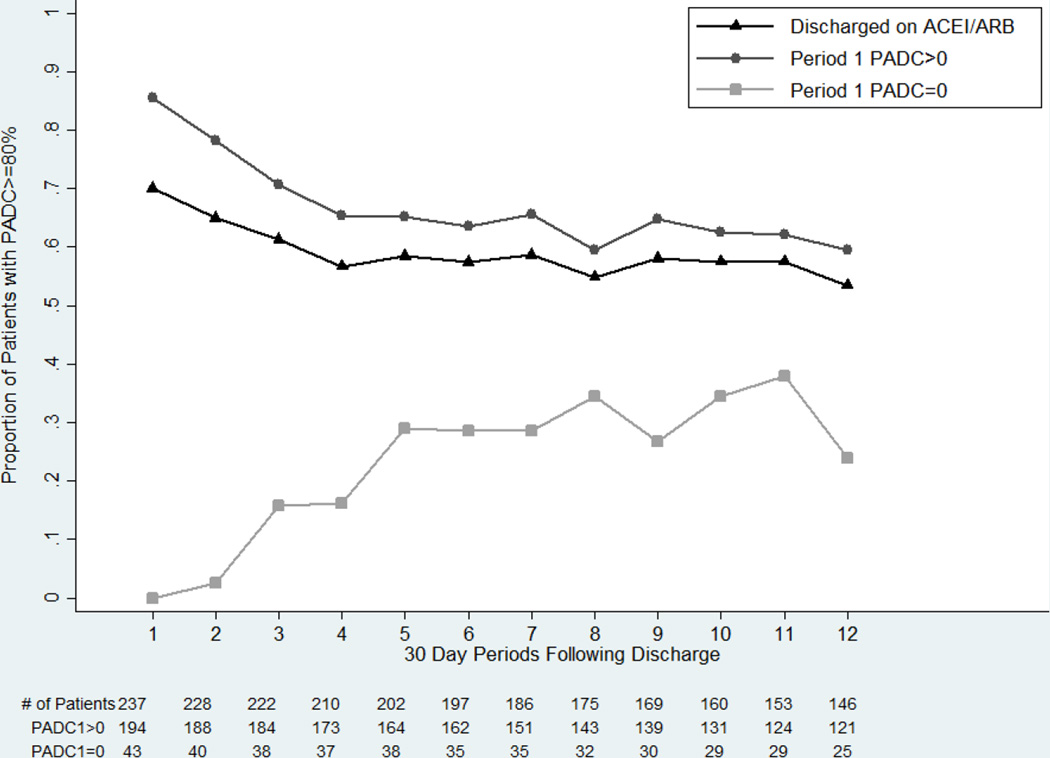

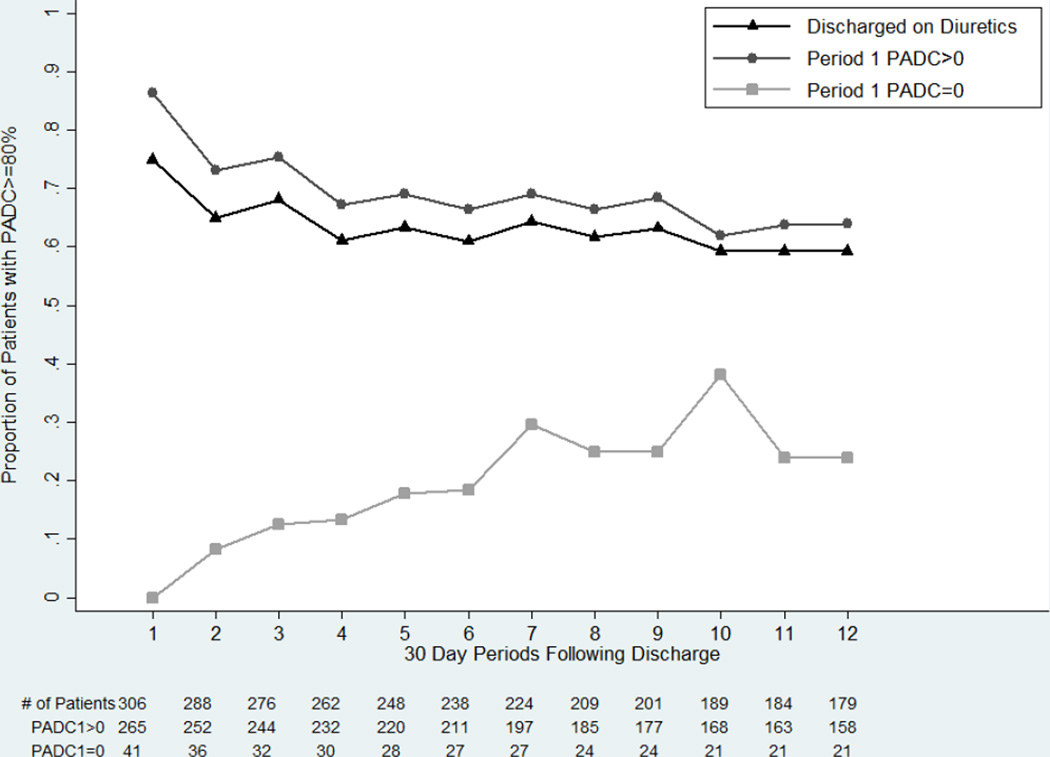

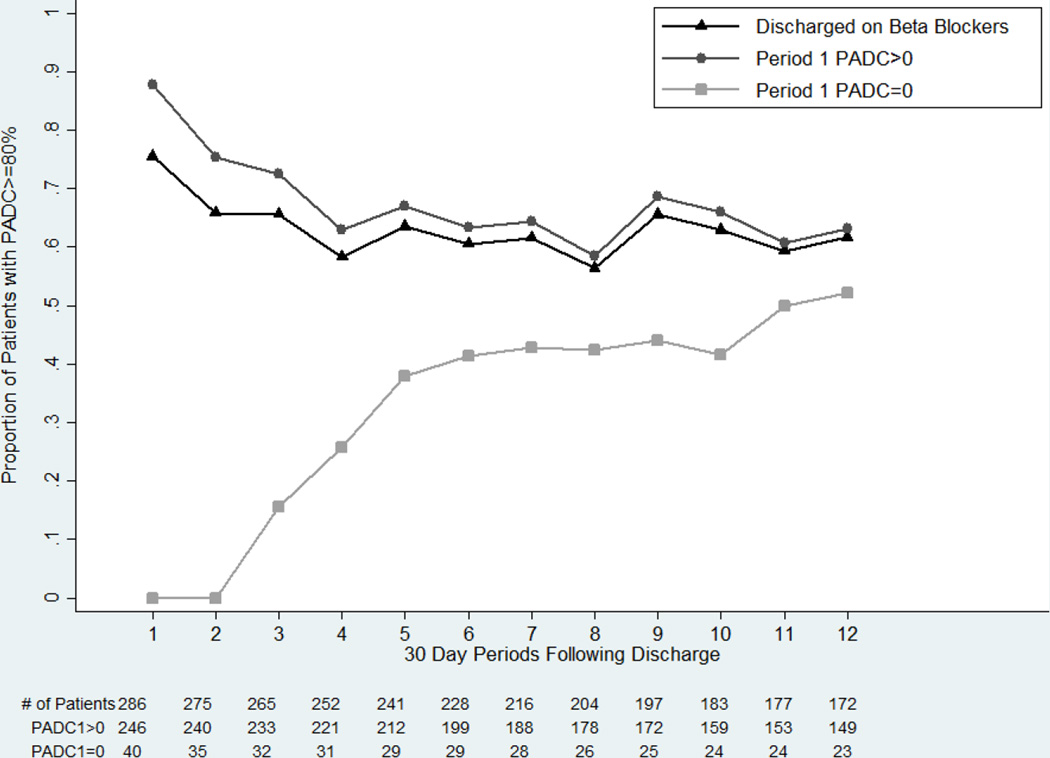

Medication adherence as measured by PADC was suboptimal (<80%) and declined after discharge for each medication class (Figures 1–3). Overall, adherence at 1, 3 and 12 months was: 70%, 61%, 53% for ACEI/ARB, 76%, 66%, 62% for BB, and 75%, 68%, 59% for diuretics. Participants with a medication fill during the first 30 day period after discharge, PADC >0, demonstrated a higher adherence during subsequent periods. If the PADC was >0 in the first 30 day period, adherence at 1, 3 and 12 months was: 86%, 71%, 60% for ACEI/ARB, 88%, 73%, 63% for BB, and 86%, 75%, 64% for diuretics. Adherence declined the most over the first 2–4 months after hospital discharge for all three medication classes. For participants who did not have a medication fill within 30 days of discharge (PADC = 0 in the first period), medication adherence was poor (i.e., <80% PADC). Adherence to ACEI/ARB and diuretics never exceeded 40% over the study period. Adherence to BB improved over time but remained low. We also calculated the proportion of participants with non-persistence, defined as those who did not have a medication fill for ≥90 consecutive days, and those with discontinuation defined as non-persistence with no subsequent medication claims. At least 1 episode of non-persistence was observed in 25% of participants prescribed an ACEI/ARB, and 16% for both BB and diuretics. Discontinuation was documented in 21%, 12%, and 11% of participants prescribed an ACEI/ARB, BB, and diuretic, respectively.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients discharged on ACEI/ARB with PADC ≥80% by 30 day periods after hospital discharge

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients discharged on diuretics with PADC ≥80% by 30 day periods after hospital discharge

We explored bivariate associations between adherence to individual drug classes over the first 3 months after hospitalization and participant characteristics listed in Table 1. We found a limited number of associations that were significant at p ≤0.05. (Table 3) Blacks in Jackson and Forsyth had lower adherence than whites for ACEI/ARB and BB. Relative to participants in other sites, participants in Washington County, MD were more adherent to ACEI/ARB and BB. Participants with lung disease had worse adherence to BB. Higher serum creatinine was associated with worse adherence to ACEI/ARB therapy. Adherence to any single drug class was positively associated with the likelihood of being adherent to the other discharge medication classes. Age, gender, other comorbidities, hospitalization due to ADHF compared to chronic HF, assessment of LVEF during hospitalization, any documentation of LVEF, LVEF <50% or ≤40%, heart rate, or length of stay were not associated with medication adherence.

Table 3.

Predictors of Medication Adherence

| ACEI/ARB | Beta Blockers | Diuretics | ||||

|

Dichotomous Characteristics |

Percent with PADC≥80% |

P value |

Percent with PADC≥80% |

P value |

Percent with PADC≥80% |

P value |

| Race | ||||||

| Black (Jackson, Forsyth) | 51 % | 0.05 | 50% | <0.01 | 62% | 0.58 |

| White | 63% | 69% | 65% | |||

| ARIC Site ^ | ||||||

| Jackson | 49 % | 0.02 | 49% | <0.01 | 60% | 0.26 |

| Forsyth County | 54% | 0.48 | 62% | 0.83 | 72% | 0.06 |

| Minneapolis | 64% | 0.34 | 71% | 0.11 | 51% | 0.34 |

| Washington County | 54% | 0.01 | 58% | 0.02 | 63% | 0.76 |

| Prior HF Hospitalization | ||||||

| Yes | 50 % | 0.05 | 61% | 0.46 | 66% | 0.59 |

| No | 65% | 56% | 69% | |||

| Lung Disease | ||||||

| Yes | 56 % | 0.71 | 52% | 0.01 | 65% | 0.64 |

| No | 59% | 67% | 62% | |||

| ACEIARB PADC≥80% | ||||||

| Yes | 75% | <0.01 | 79% | <0.01 | ||

| No | 38% | 43% | ||||

| Beta Blocker PADC≥80% | ||||||

| Yes | 74 % | <0.01 | 74% | <0.01 | ||

| No | 37% | 48% | ||||

| Diuretics PADC≥80% | ||||||

| Yes | 71 % | <0.01 | 72% | <0.01 | ||

| No | 33% | 46% | ||||

| ACEI/ARB | Beta Blockers | Diuretics | ||||

| Continuous Measures | Value | P value | Value | P value | Value | P value |

| Serum Creatinine (Worst) | ||||||

| PADC≥80% | 1.61 | <0. 01 | 1.98 | 0.70 | 1.75 | 0.54 |

| PADC<80% | 2.13 | 2.05 | 1.83 | |||

HF = heart failure; ACEI/ARB = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker.

Comparison for site is the p-value for each site versus all other sites combined.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate monthly medication adherence to ACE-I/ARB, BB, and diuretics immediately after hospitalization in patients with validated HF using Medicare Part D data with chart documentation of discharge medications. These ARIC participants should not have had a contraindication to ACE-I/ARB or BB therapy since they were prescribed at discharge. We found that adherence to all 3 medication classes was not optimal and declined over time, with the largest decrease occurring during the first 2–4 months after hospital discharge. Approximately 60% of the sample was adherent from the fourth month onward.

In the prior study most similar to ours, Butler et al. reported only ACE-I/ARB use measured by fill frequency in Medicaid patients hospitalized with HF during 1998–2001.9 In our more contemporary older cohort, we found a higher initial adherence rate for ACEI/ARB. However, adherence declined to similarly low levels by month 4. We saw a similar pattern for BB. Adherence to diuretics, not previously reported, was characterized by a less steep decline over the first few months post discharge which may reflect the immediate symptom relief with this therapy.

Other prior US studies have reported low (35–61%) long-term utilization, generally over a 1-year period.1, 3, 6, 8 Medication adherence was based on filled prescriptions which may overestimate adherence. A few studies have utilized Part D data but have not reported adherence immediately post discharge. Part D implementation has resulted in modest improvements in medications adherence as reported by Donohue et al.7 Zhang et al. reported 52% of patients had good adherence for HF medications up to one year in a 5% sample of Medicare fee for-service beneficiaries with 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient claims for HF during 2007–2009.5 Adherence to individual medications was not reported. In our study, short-term adherence rates for ARIC participants with PADC ≥80% in the first month were substantially higher but declined by 22–26% to similar rates by the end of the study, 63%, 60%, and 64% for BB, ACE-I, and diuretics, respectively. Our data highlight the need to identify the predictors for the early decline in adherence after hospitalization in order to develop appropriate interventions. Our data suggest that focused interventions to improve adherence should extend over several months post-discharge to maintain the higher 30 day adherence rates.

A recent literature review by Oosterom-Calo concluded that predictors of medication adherence were inconsistent for age, gender, ethnicity, social support, functional status, depression, patient perceived barriers, and number of comorbidities.14 Single studies found that coronary artery disease, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and asthma/chronic obstructive lung disease were associated with increased adherence, while renal disease was associated with lower adherence. The only consistent predictor of good adherence was history of hospitalization or a nursing home stay. In our study, worse renal function and previous HF hospitalization were associated with poor adherence to ACEI/ARB. Lung disease was associated with poor adherence to BB. Subsequent studies have reported geographic and ethnic variation in medication adherence.4, 5 Although we observed differences in patterns of medication adherence to ACEI/ARC and BB by ARIC geographic site, we were not able to separate out the residual confounding effects of race and unmeasured area-specific healthcare systems characteristics. We examined several variables not commonly reported in previous studies. In our study, post discharge adherence does not appear to be different between participants admitted with an ADHF compared to those admitted with chronic stable HF. Ejection fraction was not associated with adherence measured either as a continuous variable or as a categorical variable based on a priori-defined cut points: <50% and <40%. Adherence to any single drug class was highly correlated with being adherent to other medication classes. This finding suggests that medication non-adherence is not solely due to adverse effects or discontinuation. Our findings confirm the complexity of predictors of medication adherence and suggest that adherence may depend not only on the specific medication but also the patient population.

This analysis is subject to several limitations. The results may not be generalizable to patients who are not on Medicare Part D, though we were able to include both Medicare fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage. Our measure of adherence could be too low if claims are missing due to participants being in the donut hole or receiving medications through a generic drug plan, or veteran drug benefits. However, many pharmacies continue to submit claims to Medicare even when the beneficiary is responsible for the full payment.15–17 A study of medication adherence in patients with depression and HF showed only a modest reduction in adherence for persons in the donut hole,.15 We excluded veterans who never filed a medication claim. Medicare Part D claims were never filed for 6–9% of our participants (23/248 for ACEI/ARB, 18/305 for BB and 21/321 for diuretics). However, approximately 60% of these participants had claims filed for other medications, consistent with non-adherence rather than missing claims. Also, medication adherence still declined between 22–26% for all 3 medication classes over the study period among participants with an initial fill. ARIC does not collect follow up visit data post discharge so we did not have data on medication discontinuation by providers e.g. due to worsening renal function. Strengths of our study include: examining adherence in patients with known discharge medications, not just users; identifying patterns of adherence over time; the adjudication of hospitalizations with differentiation between acute exacerbation vs chronic stable HF; and clinical data not available through claims e.g. LVEF, laboratory values.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients discharged on beta blockers with PADC ≥80% by 30 day periods hospital discharge

Acknowledgments

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Tim Carey provided extremely helpful comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Sun SX, Ye XL, Lee KY, Dupclay L, Plauschinat C. Retrospective Claims Database Analysis to Determine Relationship Between Renin-Angiotensin System Agents, Rehospitalization, and Health Care Costs in Patients with Heart Failure or Myocardial Infarction. Clin Ther. 2008;30:2217–2227. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamb DA, Eurich DT, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT, Semchuk WM, Wilson TW, Blackburn DF. Changes in Adherence to Evidence-Based Medications in the First Year After Initial Hospitalization for Heart Failure Observational Cohort Study From 1994 to 2003. Circ-Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:228–235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.813600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setoguchi S, Choudhry NK, Levin R, Shrank WH, Winkelmayer WC. Temporal Trends in Adherence to Cardiovascular Medications in Elderly Patients After Hospitalization for Heart Failure. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:548–554. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang YT, Wu SH, Fendrick AM, Baicker K. Variation in Medication Adherence in Heart Failure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:468–470. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang YT, Baik SH. Race/Ethnicity, Disability, and Medication Adherence Among Medicare Beneficiaries with Heart Failure. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:602–607. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2692-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagchi AD, Esposito D, Kim M, Verdier J, Bencio D. Utilization of, and adherence to, drug therapy among medicaid beneficiaries with congestive heart failure. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1771–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donohue JM, Zhang YT, Lave JR, Gellad WF, Men A, Perera S, Hanlon JT. The Medicare drug benefit (Part D) and treatment of heart failure in older adults. Am Heart J. 2010;160:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgerald AA, Powers JD, Ho PM, Maddox TM, Peterson PN, Allen LA, Masoudi FA, Magid DJ, Havranek EP. Impact of Medication Nonadherence on Hospitalizations and Mortality in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2011;17:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler J, Arbogast PG, Daugherty J, Jain MK, Ray WA, Griffin MR. Outpatient utilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors among heart failure patients after hospital discharge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2036–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJV, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WHW, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Creager MA, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810–1852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, Zheng ZJ, Sueta CA, Coker-Schwimmer EJ, Arvanitis MLohr KN, Middleton JC, Jonas DE. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;3:774–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study - Design and Objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Baggett C, Johnson A, Bertoni AG, Shahar E, Deswal A, Heiss G, Chambless LE. Classification of Heart Failure in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study A Comparison of Diagnostic Criteria. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:152–159. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oosterom-Calo R, van Ballegooijen AJ, Terwee CB, te Velde SJ, Brouwer IA, Jaarsma T, Brug J. Determinants of adherence to heart failure medication: a systematic literature review. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18:409–427. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9321-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baik SH, Rollman BL, Reynolds CF, Lave JR, Smith KJ, Zhang YT. The Effect of the US Medicare Part D Coverage Gaps on Medication Use Among Patients with Depression and Heart Failure. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2012;15:105–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuart B, Loh EF. Medicare Part D Enrollees' Use of Out-of-Plan Discounted Generic Drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:387–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuart B, Loh FE. Medicare Part D Enrollees' Use of Out-of-Plan Discounted Generic Drugs, Revisited Response. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:310–310. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]