Abstract

There are numerous cell types with scarcely understood functions, and whose interactions with the immune system are not well characterized. To facilitate their study, we generated a mouse bearing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-specific CD8+ T-cells. Transfer of the T-cells into EGFP reporter animals killed GFP-expressing cells, allowing selective depletion of desired cell types, or interrogation of T-cell interactions with specific populations. Using this system, we eliminate HCN4+ GFP-expressing cells in the heart and elicit their importance in cardiac function. We also show that naïve T-cells are recruited into the mouse brain by antigen-expressing microglia, providing evidence of an immune surveillance pathway in the central nervous system. The just EGFP death-inducing (JEDI) T-cells enable visualization of a T-cell antigen. They also make it possible to utilize hundreds of GFP-expressing mice, tumors, and pathogens, to study T-cell interactions with virtually any cell type, to model disease states, or to determine the functions of poorly characterized cell populations.

The surface of all nucleated cells contain MHC class I molecules that present peptides from endogenously expressed proteins1. T-cells scan the surface of a cell, and engage only cells in which their T-cell receptor (TCR) has affinity for a specific peptide-MHC (pMHC) complex. The outcome of T-cell engagement is not only dependent on TCR affinity for the pMHC, but also highly dependent on the nature of the cell presenting the antigen and the local mileu2,3. While we know how T-cells interact with some cell populations, T-cell interactions with many cell types, especially rare cell populations, have never been specifically studied3.

The predominant means by which T-cell interactions with specific cell types have been studied is through the use of T-cells engineered to express a T-cell receptor (TCR) that recognizes a single pMHC complex4,5. These models have been invaluable in advancing our understanding of immunology6,7. However, the study of T-cell interactions with their antigen-expressing targets has been limited by two factors in particular: technological difficulties in tracking and monitoring antigen-expressing cells and the lack of animals and reagents that express a model antigen in specific cell types. The limitation of current tools in part underlies our incomplete understanding of the heterogeneity in T-cell responses between tissues and cells.

Not only are there cell types whose interactions with the immune system are poorly studied, there are also cell populations whose functions have not been well characterized. This is also largely due to technological restrictions; in particularly the paucity of current methods to deplete specific cell populations. Depletion of a cell can be achieved using certain antibodies or by engineering mice to express the human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) under the control of a cell type-specific promoter and injecting diphtheria toxin (DT)8,9, but there are relatively few depleting antibodies or DTR mice available. Moreover, repeat administration of the antibody or DT is required to stably deplete cell types that are renewed, such as lymphocytes.

To address these challenges, we reasoned that EGFP could be used as a model antigen. EGFP is readily detected by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy, and there are hundreds of EGFP-expressing mice available10, as well as EGFP-expressing cancer cell lines, viruses, bacteria, and other tools. Here, we generated a mouse expressing an EGFP-specific TCR and show that this model enables wide-ranging studies of T-cell-tissue interactions and specific and stable depletion of rare cell populations.

RESULTS

Generation of an EGFP-specific CD8+ T-cell mouse

To generate mice expressing an EGFP-specific TCR, we used a somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) approach11. SCNT has the benefit that the rearranged TCR is regulated at its endogenous locus, and does not require the use of cultured T-cell clones. We crossed BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, and immunized F1 progeny mice (B6xBalbc) with a lentivirus encoding EGFP (LV.EGFP). After 2 weeks, we used a tetramer to isolate CD8+ T-cells expressing TCRs specific for the immunodominant epitope of EGFP (EGFP200-208) presented on H-2Kd12. We directly used the cells as a nuclear donor for SCNT (Fig. 1a). We used B6xBalbc mice because SCNT is most efficient on a mixed background11, and because we wanted the EGFP-specific T-cells to recognize EGFP presented on H-2Kd. The H-2Kd allele enables a diverse use because BALB/c, NOD, and NOD/SCID all have the H-2Kd allele, and there are strains of C57BL mice with the H-2Kd haplotype, most notably B6D2 and B10D2. As such, any mouse model on the C57BL/6 strain can be bred with B6D2 or B10D2 mice and all first generation progeny will express the H-2Kd allele. In addition knowledge of the immunodominant epitope presented on H-2Kd allows detection of EGFP-specific CD8+ T-cells with a tetramer. The F1 mice were backcrossed for 8 generations to B10D2 mice so that they expressed H-2Kd allele, and were on the C57BL background. More than 50% of CD8+ T-cells in all mice were specific for GFP200-208-H-2Kd pentamer and their phenotype was naïve (CD44−CD62L+) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). PCR analysis and Sanger-sequencing revealed that the rearranged TCR was Vα1-J30 and Vβ4-D1-J1.6-C1 (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

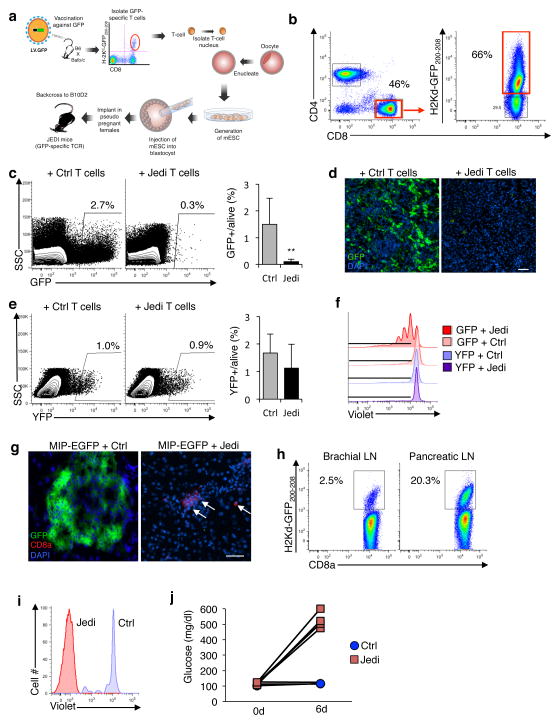

Figure 1. JEDI T-cells specifically kill EGFP-expressing cells and can be used to study pathogen clearance and model autoimmune disease.

(a) Schematic of the methodology used to make the JEDI mice. (b) Splenocytes from JEDI mice were stained with CD3e, CD4, CD8a antibody, and an H-2Kd-GFP200-208 pentamer to measure the frequency of EGFP-specific T-cells. (c) Mice were injected with a lentivirus expressing EGFP (LV.EGFP) and 2 days later JEDI or control (Ctrl) CD8+ T-cells were injected. Flow cytometry was performed to measure EGFP-expressing cells in the spleen after 5 days. Shown is a representative dotplot from two separate experiments. Graph presents mean±s.d. of the percentage of EGFP+ cells among live splenocytes (n= 7 mice/group). **P<0.01 vs Control-treated. (d) Fluorescent microscopy analysis of the spleen of mice described in (c). Representative images are shown. White bar represents 100 μm. (e) Mice were injected with LV expressing EYFP (LV.EYFP) and 2 days later JEDI or control CD8+ T-cells were injected. Flow cytometry was performed to measure EYFP-expressing cells in the spleen after 5 days. Shown is a representative dotplot from two experiments (left). Graph presents the mean±s.d. of EYFP+ cells among live splenocytes (n=3 mice/group). (f) Bone marrow cells were transduced with LV.EYFP or LV.EGFP and differentiated into dendritic cells (BMDCs). Isolated JEDI or B10D2 CD8+ T-cells were stained with Violet Cell Proliferation dye and added to BMDCs. EGFP-specific cells were identified by H-2Kd-GFP200-208 pentamer staining. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown (n=3 wells/group). (g) MIP-EGFP mice were injected with 1×106 JEDI or control CD8+ T-cells, and vaccinated with EGFP. Fluorescent microscopy analysis of the pancreas was performed 6 days after T-cell transfer. Representative images are shown (n=4 mice/group). Arrows point to CD8+ cells in the tissue. White bar represents 100 μm. (h) Flow cytometry of H-2Kd-GFP200-208 pentamer positive CD8+ T-cells in the brachial and pancreatic lymph nodes of MIP-EGFP mice injected with JEDI T-cells as in (g). (i) MIP-EGFP mice were injected with 2×106 Violet Cell Proliferation dye-labeled JEDI or control CD8+ T-cells, and 6 days later proliferation was measured in the CD8+ T-cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes. EGFP-specific T-cells were identified by H-2Kd-GFP200-208 pentamer staining. Representative histogram is shown (n=2 mice/group). (j) Blood glucose measurements at the indicated times of mice described in (g) (n=4 mice/group).

Use of JEDI T-cells to study pathogen clearance

Monitoring antigen expressing cells and their clearance by T-cells is particularly relevant in viral immunology13. To determine if we could use our EGFP-specific T-cells to monitor removal of infected cells, we injected mice with a lentivirus (LV) encoding EGFP (LV.EGFP)14, or with an LV encoding yellow florescent protein (LV.EYFP), which has >95% homology to EGFP, but differs by one amino acid in the immunodominant epitope (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We then transferred CD8+ T-cells from the SCNT-derived or control mice.

In mice that received control T-cells, ~2% of splenocytes were EGFP+, whereas in mice that received SCNT-derived T-cells, EGFP+ cells were almost all eliminated, which indicated that these T-cells were capable of killing EGFP-expressing cells (Fig. 1c,d). Instead, splenocytes from mice infected with LV.EYFP were not killed (Fig. 1e). To further assess the specificity of the SCNT-derived T-cells, we co-cultured them with dendritic cells (DC) expressing EGFP or EYFP, and found that the T-cells only proliferated in the presence of EGFP (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 2c). These results demonstrate the specificity and cytotoxic capacity of the SCNT-derived T-cells for EGFP expressing cells. We thus named them JEDI, for just EGFP death inducing.

JEDI facilitate visualizable and inducible autoimmune model

Antigen-specific T-cells are commonly used to model different autoimmune diseases6. A potential advantage of using JEDI T-cells over existing models is that they would enable qualitative and quantitative assessments at a cellular level, such as whether all target cells are killed. To test this, we used JEDI T-cells to induce type I diabetes (T1D). We injected mice that express EGFP under the control of the mouse insulin promoter (MIP-EGFP)15 with JEDI or control T-cells, and vaccinated them with EGFP to activate the transferred cells. Within 6 days of injecting JEDI T-cells, we could not find any EGFP+ β-cells in the pancreas (Fig. 1g). Analysis of EGFP200-208-H-2Kd pentamer+ cells found that the EGFP-specific T-cells had primarily localized to the pancreatic draining lymph node (Fig. 1h) and undergone proliferation (Fig. 1i). Accordingly, MIP-EGFP mice that received JEDI T-cells were diabetic, as indicated by their loss of glucose control (Fig. 1j). Since there are numerous tissue-specific EGFP-expressing mice, the JEDI make it possible to create tissue immunity models, and to precisely monitor the T-cell and target cell interactions in these models.

Investigate T-cell trafficking into brain with JEDI T-cells

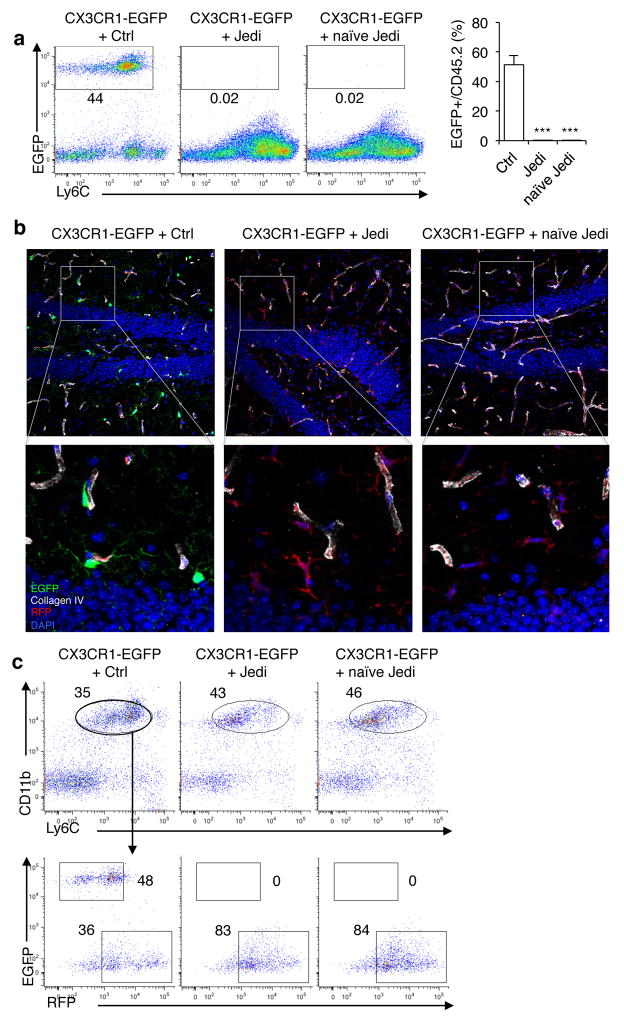

While tools have been available to study antigen-dependent T-cell interactions with β-cells, there are other cell types that have no such tools, and this has left unanswered questions. For example, for microglia, the brain resident macrophages, it is unclear whether under homeostatic conditions in the brain CD8+ T-cells survey these cells, as the blood brain barrier (BBB) is believed to keep the brain mostly inaccessible to cellular infiltrates in the absence of inflammation16. To study the antigen presenting capacity of microglia, we took advantage of the CX3CR1-EGFP mice17, which express EGFP in microglia. Because CX3CR1 mice express EGFP also in circulating monocytes and some other myeloid cells, we lethally irradiated the mice, which ablated all the peripheral myeloid cells but spared microglia, since they are radioresistant18. We then transplanted the irradiated recipients with bone marrow from Actin-RFP mice. After 10 weeks, the hematopoietic cells in the periphery were all RFP+ and EGFP−, indicating that engraftment of the Actin-RFP cells was complete, but the microglia were still EGFP+ (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c).

We transferred JEDI or control CD8+ T-cells into the CX3CR1-EGFP/Actin-RFP mice (with EGFP+ microglia, RFP+ peripheral hematopoietic cells) at 10 weeks post-bone marrow transplant, a time by which the BBB has fully repaired from irradiation, and is not even permissible to serum albumin19. After transfer the mice were either vaccinated with EGFP or left unvaccinated to keep the T-cells naïve. Remarkably, within 1 week all of the EGFP+ microglia were eliminated from mice that received JEDI T-cells, even those that were not vaccinated (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3d). This was concomitant with the presence of JEDI T-cells, but not control T-cells, in the brain (Supplementary Fig. 3e,f). The EGFP+ microglia remained absent after 3 weeks, but there were RFP+ macrophages (CD45intLy6cintCD11b+RFP+) in the brain (Fig. 2b,c), which is consistent with previous reports that peripheral monocytes can replace microglia after injury20,21, and extends this observation to the context of CD8+ T-cell-mediated clearance.

Figure 2. JEDI T-cells reveal naïve T-cell can cross the blood brain barrier and kill antigen-expressing microglia.

(a) CX3CR1-EGFP mice were transplanted with bone marrow from actin-Red Fluorescence Protein (RFP) mice. Ten weeks later mice were injected with 5×105 Ctrl or JEDI CD8+ T-cells. A cohort were vaccinated with EGFP while another cohort was not vaccinated (naïve JEDI). Quantification of EGFP-expressing microglia was performed 1 week after T-cell transfer. Representative plots are shown (left). Graph (right) presents the mean±s.d. of the frequency of microglia in the brains of the mice (n=3 mice/group). ***P<0.001 vs Control-treated. (b) Representative images of the dentate gyrus of hippocampus 3 weeks after injection of the CD8+ T-cells and 13 weeks after BMT. Collagen IV denotes vessel basement membrane. 20x magnification, bar represents 50 μm. (c) The brains of CX3CR1-EGFP mice transplanted with RFP-expressing BM, and injected with Ctrl or JEDI CD8+ T-cells at 10 weeks post-BMT (as in c), were analyzed 3 weeks after injection of the T-cells to quantitate the number of EGFP+ and RFP+ microglia (CD45intLy6cintCD11b+). Representative flow cytometry plots are shown from n=3 mice/group.

These findings indicate that naïve T-cells can enter the brain when microglia present an antigen recognized by the T-cells and suggests the existence of an immune surveillance pathway for the brain that is mediated by microglia. Further work will be necessary to better understand the mechanisms involved. In particular, it will be relevant to determine if other antigen presenting cells play a role through cross-presentation of antigen derived from the microglia. It will also be important to confirm our findings in a model in which irradiation was not used because we cannot rule out the possibility that irradiation had somehow altered the BBB.

JEDI can be used to stably deplete a cell population

The rapid clearance of EGFP-expressing microglia and β-cells by the JEDI T-cells led us to reason that these cells may also have utility as a method for depleting cells to study their function.

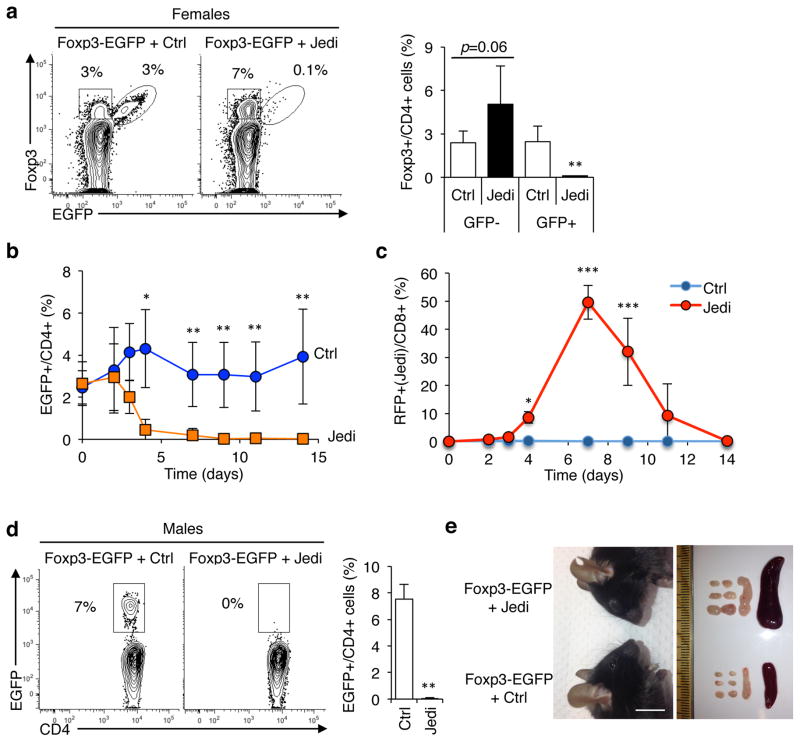

We first tested whether we could phenocopy an established cell depletion model using JEDI T-cells. We selected Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells (Treg) as a target because the phenotype of Treg depletion is known22, although whether CD8+ T-cells could kill Tregs was unknown. In addition, Tregs are a renewing population so we could use them to assess the stability of cell depletion. To determine if JEDI T-cells could be used to deplete Tregs, we injected Foxp3-EGFP mice with JEDI or control T-cells. In Foxp3-EGFP mice, EGFP has been knocked in to the Foxp3 gene on the X chromosome23. We initially injected heterozygous female Foxp3-EGFP mice. Due to random X inactivation ~50% of the Tregs are Foxp3+EGFP+, and the other 50% are Foxp3+EGFP− (Fig. 3a). Within 6 days of injecting activated JEDI T-cells, there was a complete elimination of Foxp3+EGFP+ cells (Fig. 3a,b). The Foxp3+EGFP− cells were not depleted, but instead increased in numbers to compensate for the loss of the EGFP+ Tregs. Depletion was maintained for up to 14 days (last time assessed) without any need to transfer more T-cells or to re-vaccinate (Fig. 3b), and the frequency of JEDI T-cells contracted to very low levels (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. JEDI T-cell can stably deplete a renewing cell population to study their function.

(a) Representative flow cytometry analysis and quantification of the frequency of EGFP+ Foxp3+ cells in LN of Foxp3-EGFP females 15 days after T-cell transfer. Mice were injected with 1×106 JEDI T-cells and vaccinated immediately after. Cells were stained with CD3e, CD4, CD25 and Foxp3 to mark regulatory T-cells (n=5 mice/group). **P<0.01 vs Control-treated. (b) Foxp3-EGFP female mice were injected with either control (Ctrl) or JEDI T-cells. Percentage of EGFP+ cells among CD4+ T-cells was determined in the blood at the indicated time points (n=5 mice/group). *P<0.05 vs Control-treated, **P<0.01 vs Control-treated, ***P<0.01 vs Control-treated. (c) Percentage of JEDI T-cells among CD8+ T-cells was determined in the blood at the indicated time points from the mice described in (b) (n=5 mice/group). The JEDI mice and control littermates were transgenic actin-RFP (red florescent protein). (d) Foxp3-EGFP male mice were treated with either 5×105 control (Ctrl) or JEDI T-cells and vaccinated immediately after. Flow cytometry analysis of the frequency of EGFP+ cells in the LN 10 days after T-cell transfer. (n=3–4 mice/group). **P<0.01 vs Control-treated. (e) Representative image of the face of Foxp3-EGFP mice showing conjunctivitis in the JEDI-treated mice (left) and image of the brachial, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes and the spleen taken from control-treated and JEDI-treated Foxp3-EGFP mice 10 days after adoptive transfer (right) (n=3–4 mice/group). White bar represents 1 cm.

Next, we injected male Foxp3-EGFP mice in which all Foxp3+ cells are EGFP+. Within 6 days there was complete depletion of Foxp3+EGFP+ Tregs (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). By 10 days all the JEDI- treated Foxp3-EGFP mice had become ill and showed clear indications of immune dysregulation, including conjunctivitis, splenomegaly, enlarged lymph nodes and expansion of neutrophils (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 4c); consistent with the phenotype of Treg-depleted mice22. We investigated the influence of T-cell dosage on target cell depletion by injecting Foxp3-EGFP male mice with 5×104, 1.5×105, or 5×105 CD8+ JEDI T-cells. At the two highest cell doses, EGFP+ cells were completely eliminated in all Foxp3− EGFP mice injected, whereas at the lowest cell dose EGFP+ cells were eliminated in 2 out of 3 mice, but in 1 Foxp3-EGFP mouse the JEDI T-cells did not expand and EGFP+ cells were not eliminated (Supplementary Fig. 4d,e). Thus, there appears to be a cell dose threshold for efficient killing, which is likely to depend on the nature of the EGFP-expressing mouse model.

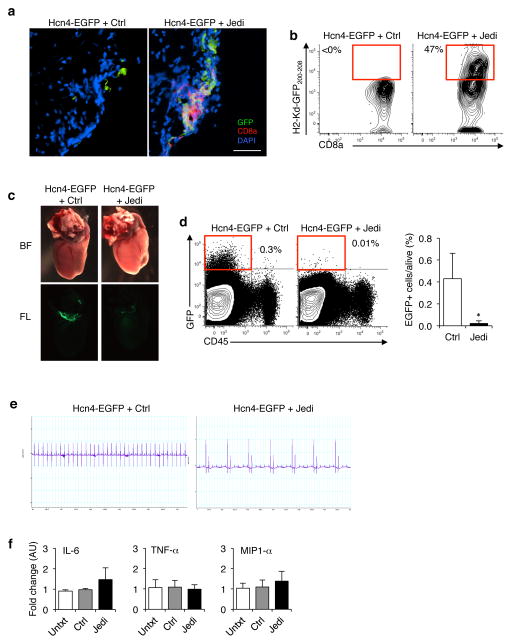

JEDI can be used for loss-of-cell-function studies

To determine if we could use the JEDI to eliminate a rare cell population in a non-lymphoid organ, we targeted Hcn4+ cells. These cells are found in the heart and are extremely rare; there are <10,000 Hcn4+ cells in a mouse24. They are known to be involved in pacemaking, but there are conflicting reports regarding the overall importance of Hcn4+ cells in cardiac function25,26. We injected Hcn4-EGFP mice24, which express EGFP under the control of the Hcn4 promoter, with JEDI or control T-cells, and vaccinated them with EGFP. Within 5 days we could detect CD8+ T-cells co-localizing with EGFP+ cells in the heart (Fig. 4a). Pentamer staining indicated that these cells were JEDI T-cells (Fig. 4b). Strikingly, by 10 days the Hcn4-EGFP cells were entirely absent from the heart of the JEDI T-cell injected Hcn4-EGFP mice (Fig. 4c). Uniquely from other depletion technologies, we were able to assess target cell depletion at single cell resolution using flow cytometry, and were able to confirm that the JEDI T-cells completely eliminated the Hcn4+ cells from the hearts (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4. JEDI T-cells can deplete rare cell populations to study their function.

(a) Florescent microscopy images of the heart 5 days after transfer of 5×106 JEDI T-cells and vaccination against EGFP. Sections were stained with CD8a to mark CD8+ T-cells. Representative image is shown (n=3 mice/group). White bar represents 100 μm. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of the heart at 5 days after T-cell transfer to measure the frequency of EGFP-specific T-cells. Cells were stained for CD45, CD8a, CD3e, and H-2Kd-GFP200-208 pentamer. (c) Hcn4-EGFP mice were injected with 5×106 JEDI or control CD8+ T-cells, and vaccinated with EGFP. Low magnification (2x) whole mount bright field (BF) and fluorescent (FL) images of the hearts at 10 days post-transfer. (d) Flow cytometry analysis of the frequency of EGFP+ cells in the heart 10 days after T-cell transfer. Cells were stained with CD45 to mark hematopoietic cells in the heart. Dotplots are representative of 2 experiments. Graph presents the mean±s.d. of the frequency of EGFP expressing cells in the heart (n=4 mice/group). *P<0.05 vs Control-treated. (e) Electrocardiogram (ECG) on the mice treated in (a). Images are representative of 2 experiments (n=4 mice/group). (f) RT-qPCR analysis of inflammatory cytokine mRNA levels in the heart of Hcn4-EGFP mice treated in Fig. 4a. Graphs present mean±s.d. relative to untreated (n=4 mice/group).

We then performed an electrocardiogram (ECG) on the mice after depletion of Hcn4+ cells to determine the outcome of depletion on cardiac function. Whereas mice injected with control T-cells had a normal ECG, all mice injected with JEDI T-cells presented with bradycardia and atrioventricular block (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 5). This was not due to immune cell infiltration or inflammation because by 10 days there was no evidence of increased T-cells or pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hearts of the mice (Fig. 4f). These findings support the role of Hcn4+ cells in cardiac conduction and pacemaking. They also demonstrate that JEDI T-cells can home to and kill EGFP-expressing cells even in non-lymphoid, non-inflamed tissue, and provide a means of targeted cell depletion.

DISCUSSION

There are many areas of immunological research where the JEDI will be particularly valuable because of the ability to visualize the antigen and to take advantage of the numerous existing EGFP-expressing reagents. These include identifying tolerogenic or immune privileged cell types, testing of cell-targeted vaccines, monitoring T-cell trafficking to antigen-expressing cells in normal and diseased tissues, studying T-cell interactions with particular cell types and cell states within a tumor as well as nascent metastasis, and for identifying CTL-resistant cancer cells, which will be greatly facilitated by the ability to flow sort surviving cells. It will also be possible to use the JEDI to create novel models of tissue autoimmunity and organ rejection, and for studying pathogen clearance, in a manner more accessible to state-of-the-art imaging, including live cell imaging. In addition to the relevance for basic biology, these applications of the JEDI will also facilitate target discovery and pre-clinical testing of immune modulatory drugs.

This work additionally demonstrates that JEDI T-cells can be used for targeted cell depletion. The main advantages of this approach over existing cell depletion methods, such as the DTR system, are the ability to easily assess the elimination of the target cells using EGFP, the stability of depletion, and the greater availability of cell type-specific EGFP-expressing models. Indeed, there are more than 1,000 different EGFP expressing mice (e.g. Supplementary Table 1), many of which express EGFP in populations whose functions are not well characterized10,27. We also note that JEDI-mediated T-cell killing is a physiological method of cell depletion since this is the natural function of CD8+ T-cells. As such, there are mechanisms to control excessive tissue damage by T-cells28. This is evident by the absence of inflammation and the contraction of the CD8+ T-cells after antigen-expressing cells are cleared. For studies in which cell ablation is used to study tissue repair, T-cell-mediated depletion may better approximate physiological conditions since one of the causes of tissue regeneration is T-cell-mediated clearance of cells.

For the studies performed here we adoptively transferred CD8+ JEDI T-cells, usually ~106, and vaccinated the recipient mice to activate and expand the JEDI T-cells. This was done to maximize the killing potential. However, the JEDI mouse could be bred directly with cell type-specific EGFP expressing mice, or mice in which EGFP expression is inducible, as an alternative approach. For applications in which transient depletion is desired, the JEDI mice could be engineered to express a suicide gene, such as DTR, so that the JEDI T-cells can be conditionally depleted. Because JEDI T-cells recognize EGFP presented on H-2Kd, they can be used in NOD/SCID-based mouse models, including human xenograft models. These applications of the JEDI will enable us to dissect how T-cells are interacting with discreet cell populations in different contexts at a very granular level, and help to determine the functions of poorly characterized cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

B10D2, Balb/c, CD45.1 (B6/SJL), Actin-RFP, MIP-EGFP15 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Foxp3-EGFP mice23 and CX3CR1-EGFP mice17 were from established colonies. Hcn4-EGFP mice were generated by YZ and MW24. Because JEDI T-cells recognize EGFP200-208 presented on H-2Kd, all mouse experiments were done with either B10D2 or in F1 progeny of B10D2 crossed to the indicated EGFP-expressing mouse. All experiments were performed when mice were 6–10 weeks-old and both male and females were used. Mice were randomly distributed minimizing the bias for cage, gender and age between groups. Investigators were not blinded to the groups. All animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of JEDI mice by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT11)

C57BL/6 and Balb/c mice were bred to generate mix background F1 mice. The mice were vaccinated against EGFP by intravenous injection of a 3×108 transducing units of a lentiviral vector encoding EGFP. Two weeks later livers and spleens were harvested for T-cell isolation. Briefly, livers and spleens were mechanically disrupted and filtered through 70μm cell strainer (ThermoFisher) to obtain a single cell suspension. A percoll gradient was used to enrich the leukocyte fraction from the livers. After red blood cell lysis using multispecies RBC lysis buffer (eBiosciences) for 2 minutes, cells were stained with GFP200-208-H2Kd APC labeled pentamer (ProImmune) following the manufacturer’s instructions. T-cells were further stained with CD8 (53-6.7)-PerCPCy5.5, CD4 (RM4-5)-APC-Alexa788, CD3e (145-2C11)-PE and B220 (RA3-6B2)-FITC (eBiosciences). GFP200-208-H2Kd-positive CD8+ T-cells were purified by sorting using Aria 5LS (BD) and directly frozen in 10% DMSO 20% FBS supplemented DMEM (Life Technologies).

For nuclear transfer into mouse oocytes, T-cells were thawed, washed with DMEM with 10% FBS to remove DMSO, and then kept on ice in a volume of 25–50microliter. Mouse oocytes were obtained from 6–8 week old B6D2F1/J females (Jackson laboratories strain 100006) by injecting 5–10IU of pregnant mare serum (PMS), followed by injection of 5–10IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 48–52 hours after PMS injection. Oocytes were retrieved 13–14 hours post-hCG injection, denuded using bovine hyaluronidase, and kept in KSOM (Millipore) until transfer. Nuclear transfer manipulations were done essentially as described29. In brief, oocytes were enucleated in GMOPS plus containing 4 μg/ml cytochalasinB. T-cells were aspirated into a microinjection pipette of 5 micrometer diameter (Humagen Piezo-15-5), applying piezo pulses at an intensity of 1 – 2 to lyse the plasma membrane of the T-cell. T-cells were then injected into the enucleated mouse oocyte using a piezo pulse at intensity 1 – 2, followed by removal of the plasma membrane surrounding the injected site to prevent lysis. At 1 – 3 hours after transfer, oocytes were activated using strontium chloride for 90 minutes, with the addition of cytochalasinB at 5 μg/ml for 5 hours. The histone deacetylation inhibitor scriptaid was added at a concentration of 250ng/ml for 12 hours to enhance reprogramming efficiency30. After 4 days of culture, the zona pellucida was removed from blastocysts and they were plated in mouse embryonic stem cell medium consisting of KO-DMEM, 12% KO-SR, NEAA, Glutamax, beta mercaptoethanol (all reagents from LifeTechnologies), and LIF (Millipore) on a mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder layer (GlobalStem). ES cell outgrowths were picked manually, then passaged enzymatically using TrypLE (Life Technologies).

The SCNT-derived embryonic stem cells were injected into blastocysts from mice on the C57BL/6 background and implanted into pseudo-pregnant female CD1 mice by the Mouse Genetics and Mouse Targeting facility in Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. JEDI mice were genotyped by PCR using the following primers: TCRα Fw: GAGGAGCCAGCAGAAGGT; TCRα Rev: TCCCACCCTACACTCACTACA; TCRβ Fw: TCAAGTCGCTTCCAACCTCAA; TCRβ Rev: TGTCACAGTGAGCCGGGTG.

T-cell adoptive transfer

CD8+ T-cells were purified from spleens and LNs (cranial, axillar, brachial, inguinal and mesenteric) of JEDI and control littermates by mechanical disruption and filtering through 70μm cell strainer. After RBC lysis, CD8+ T-cells were negatively selected using the mouse CD8+ T-cells isolation kit II from Miltenyi following manufacturer’s instructions. 5×105-5×106 JEDI or control T-cells were transferred per mouse by tail vein injection. For activation of T-cells, recipient mice were injected i.v. with 1×108 transducing units of a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors encoding green florescent protein (LV.EGFP).

Infection with EYFP and EGFP-encoding lentivirus

B10D2 mice received 3×108 TU of lentivirus encoding either Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (EYFP) or EGFP. Three days later JEDI or control littermate cells were adoptively transferred. The lentivirus were produced as previously described31. Briefly, third generation packaging plasmids along with transfer plasmids encoding EGFP or EYFP were transfected into 293T-cells by Ca3(PO4)2 transfection. Supernatants containing the vector were collected, passed through a 0.22-μm filter, and vectors were concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Titers were estimated as TU/ml on 293T-cells by flow cytometry analysis of EYFP-positive or EGFP-positive 293T-cells.

T-cell proliferation in vitro

Bone marrow was harvested from B10D2 mice by flushing tibiae and femurs with media, lysing RBCs, and plating the remaining cells in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 20 ng/ml of GM-CSF (Peprotech). The cells were transduced with either LV.EGFP or LV.EYFP overnight at day 1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. GM-CSF-supplemented media was added at day 3 of culture. CD8+ T-cells were isolated as described above and stained with eFluor450 dye (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Glucose measurement

Glucose levels were determined from a drop of blood obtained by clipping the tail using OneTouch Ultra® glucometer. All mice were tested in fed condition and no restrainer was used.

Bone marrow transplant

C57BL/6 CX3CR1-EGFP x B10D2 mice were lethally irradiated (2x 600 rad, 3 h apart using a Caesium source) and reconstituted with 5 million bone marrow cells isolated from CD45.2 Actin-RFP x B10D2 mice.

Immunofluorescence

Spleens, pancreata and hearts were harvested and frozen directly in OCT, 8 μm sections were taken and were fixed for 5 min with cold acetone prior to staining. Brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), equilibrated in 20% sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich) and embedded in OCT prior to sectioning. 10 μm sagittal brain sections were incubated with 2% goat serum, 1% BSA, Fc-Block 1:1000, 0.05% Tween-20 and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS before staining and stained in 1% goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100, Fc-Block 1:1000. RFP staining was performed with mouse RFP (GT1610) antibody (Abcam) and a secondary goat anti-mouse AF-568 (Life Technologies). Vessels in the brain were stained with rabbit anti-collagen IV, polyclonal (BioRad, #2150-1470) and a secondary goat anti-rabbit AF-647 (Life Technologies). T-cell staining was performed for 2 hours with either AlexaFluor594-conjugated anti-CD8a (clone 53-6.7 BioLegend) or CD3e staining with AlexaFluor647-conjugated anti-CD3a (clone 17A2 BioLegend) and DAPI (Vector Laboratories) for nuclei labeling. Sections were blocked with 2% rat serum and 0.5% BSA in PBS before staining. Images were obtained with an upright wide-field microscope (Nikon) equipped with a 20x lens, and analyzed with NisElements software, or with an Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope and analyzed with ZEN (Zeiss) and ImageJ softwares.

Electrocardiography

For surface electrocardiography, mice were anesthetized with 1.75% isoflurane at a core temperature of 37°C. Needle electrodes (AD Instruments) were placed subcutaneously in standard limb lead configurations. Signals were sampled using a PowerLab16/30 interface (AD Instruments). Data analysis was performed using LabChart (v 7.3.7, AD Instruments).

Flow cytometry analysis

Spleen and LNs were digested in HBBS (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS and 0.2 mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 minutes at 37°C. After filtration using 70μm cell strainer (Fisherbrand) to obtain a single cell suspension, red blood cells (RBC) in the spleen were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience) for 3 minutes. Brains were similarly digested by a Percoll gradient was used for the isolation of hematopoietic cells previous to the RBC lysis. Briefly, for the brain single cell suspensions were resuspended in a 37% Percoll (GE Healthcare) and underlayed by a 60% Percoll solution. The samples were then centrifuged at 600g for 20 minutes. Hearts were digested in 1mg/ml collagenase IV in 10% FBS HBSS for 30 min at 37°C and similarly filtered through a 70 μM cell strainer and RBC were lysed for 3 min.

The gating strategy used for the flow cytometry analysis is shown in the Supplementary Fig. 6. Samples were stained with: CD45 (30-F11) APC-Alexa780, CD8 (53-6.7)-PerCPCy5.5, CD4 (RM4-5)-APC and eFluro450, CD3e (145-2C11)-PE, H2-Kb (AF6-88.5.5.3)-APC, H2-Kd (SF1-1.1.1)-PE, CD25 (PC6.1)-PerCP-Cy5.5, FoxP3 (FJK-16s)-APC, CD11b (M1/70)-PerCP-Cy5.5, Gr1 (RB6-8C5) PE from eBioscience. DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to stain dead cells. LSR-Fortessa and LSR-II (BD) were used to acquire the samples and FlowJo® was used to analyze the data.

mRNA expression analysis

For measuring cytokine expression in tissue, hearts were collected from mice and immediately frozen in dry ice for later processing. For Tissue was homogenized in Trizol (Qiagen) by mechanical disruption by using the Tissue Disruptor (Qiagen) and the RNA was then extracted following the manufacturer’s instructions. 0.1–1 μg total RNA was reverse-transcribed for 1 hour at 37 °C using RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems). qPCR was performed using the SYBR green qPCR master mix 2x (Fermentas, Thermo Scientific) and the following primers:

Actin Fw: ctaaggccaaccgtgaaaag, Actin Rev: accagaggcatacagggaca;

IL6 Fw: TGATGGATGCTACCAAACTGG; IL6 Rev: TTCATGTACTCCAGGTAGCTATGG;

MIP1α Fw: CAAGTCTTCTCAGCGCCATA; MIP1α Rev: GGAATCTTCCGGCTGTAGG;

TNF Fw: CTGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGC; TNF Rev: TTTGAGATCCATGCCGTTG.

TCR Sequencing

To obtain the specific alpha and beta sequences of the JEDI T-cells, splenocytes from a JEDI mouse were stained with a CD3e-PE, CD8a-FITC antibodies and GFP200-208-H2Kd APC pentamer as described above. Pentamer+ CD8 T-cells were FACS-sorted in Influx Cell Sorter (BD) and resuspended in Trizol. RNA was isolated as described above. 5′RACE (Invitrogen) was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions to amplify the alpha and beta regions. A 3′ primer recognizing the constant region in alpha and the constant region in beta were used respectively. The obtained DNA fragment was cloned into a TOPO plasmid® (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions and submitted to sequencing by Sanger method. Cα primer: TGGCGTTGGTCTCTTTGAAG; Cβ primer; CCAGAAGGTAGCAGAGACCC.

Statistical analysis

No prespecified effect size was used to determine sample sizes. Differences between groups were compared by independent two tailed Student’s t-test for unequal variances. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Annoni, L. Sherman, J. Brody, J. Lafaille, S. Lira, J. Blander, and M. Feldmann for helpful discussions. We also thank Kevin Kelly and the Mouse Genetics and Mouse Targeting facility, and Adeeb Rahman and the Flow Cytometry Core for technical assistance. B.D.B. and M.M. were supported by NIH R01AI104848 and R01AI113221. BDB was also supported by a Pilot Award from the Diabetes Research, Obesity and Metabolism Institute and an Innovation Award from the JDRF. Y.Z was supported by NIH 1R01HL107376. J.A. was supported by the Robin Chemers Neustein Award, and a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) postdoctoral fellowship. V.K. was supported by a Swiss National Foundation Early Postdoc Mobility fellowship.

Footnotes

Contributions

J.A. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript, A.R., E.S.P., R.S. M.W. and V.K. performed experiments or acquired data, Y.Z. analyzed data, D.E. performed experiments, M.M. designed experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript, B.D.B. designed and supervised the research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Pamer E, Cresswell P. Mechanisms of MHC class I--restricted antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:323–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher AL, Malhotra D, Turley SJ. Lymph node stroma broaden the peripheral tolerance paradigm. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller SN, Germain RN. Stromal cell contributions to the homeostasis and functionality of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:618–629. doi: 10.1038/nri2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kisielow P, Bluthmann H, Staerz UD, Steinmetz M, von Boehmer H. Tolerance in T-cell-receptor transgenic mice involves deletion of nonmature CD4+8+ thymocytes. Nature. 1988;333:742–746. doi: 10.1038/333742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke SR, et al. Characterization of the ovalbumin-specific TCR transgenic line OT-I: MHC elements for positive and negative selection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:110–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafaille JJ. T-cell receptor transgenic mice in the study of autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2004;22:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg LJ, et al. Antigen/MHC-specific T cells are preferentially exported from the thymus in the presence of their MHC ligand. Cell. 1989;58:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito M, et al. Diphtheria toxin receptor-mediated conditional and targeted cell ablation in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:746–750. doi: 10.1038/90795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung S, et al. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8+ T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2002;17:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt EF, Kus L, Gong S, Heintz N. BAC Transgenic Mice and the GENSAT Database of Engineered Mouse Strains. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2013 doi: 10.1101/pdb.top073692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirak O, et al. Transnuclear mice with predefined T cell receptor specificities against Toxoplasma gondii obtained via SCNT. Science (80-) 2010;328:243–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1178590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gambotto A, et al. Immunogenicity of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in BALB/c mice: identification of an H2-Kd-restricted CTL epitope. Gene Ther. 2000;7:2036–2040. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norbury CC, Malide D, Gibbs JS, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Visualizing priming of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by infected dendritic cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:265–71. doi: 10.1038/ni762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agudo J, et al. The miR-126-VEGFR2 axis controls the innate response to pathogen-associated nucleic acids. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:54–62. doi: 10.1038/ni.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hara M, et al. Transgenic mice with green fluorescent protein-labeled pancreatic beta -cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E177–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00321.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. Capture, crawl, cross: The T cell code to breach the blood-brain barriers. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung S, et al. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ransohoff RM, Cardona AE. The myeloid cells of the central nervous system parenchyma. Nature. 2010;468:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nature09615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sándor N, et al. Low Dose Cranial Irradiation-Induced Cerebrovascular Damage Is Reversible in Mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, McNagny KM, Rossi FMV. Infiltrating monocytes trigger EAE progression, but do not contribute to the resident microglia pool. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nn.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamasaki R, et al. Differential roles of microglia and monocytes in the inflamed central nervous system. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1533–1549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontenot JD, et al. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor Foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu M, Peng S, Zhao Y. Inducible gene deletion in the entire cardiac conduction system using Hcn4-CreERT2 BAC transgenic mice. Genesis. 2014;52:134–140. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrmann S, Hofmann F, Stieber J, Ludwig A. HCN channels in the heart: lessons from mouse mutants. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucchi A, Barbuti A, Difrancesco D, Baruscotti M. Funny Current and Cardiac Rhythm: Insights from HCN Knockout and Transgenic Mouse Models. Front Physiol. 2012;3:240. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong S, et al. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parish IA, et al. Tissue destruction caused by cytotoxic T lymphocytes induces deletional tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3901–3906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810427106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egli D, Eggan K. Nuclear transfer into mouse oocytes. J Vis Exp. 2006;116 doi: 10.3791/116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Thuan N, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor scriptaid enhances nascent mRNA production and rescues full-term development in cloned inbred mice. Reproduction. 2009;138:309–317. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown BD, et al. Endogenous microRNA can be broadly exploited to regulate transgene expression according to tissue, lineage and differentiation state. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1457–67. doi: 10.1038/nbt1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.