Abstract

Hypothesis

Identification, characterization, and location of cells involved in the innate immune defense system of the human inner ear may lead to a better understanding of many otologic diseases and new treatments for hearing and balance related disorders.

Background

Many otologic disorders are believed to have, as part of their disease process, an immune component. While resident macrophages are known to exist in the mouse inner ear, the innate immune cells in the human inner ear are, to date, unknown.

Methods

Primary antibodies against CD163, Iba1, and CD68 (markers known to be specific for macrophages/microglia) were utilized to immunohistochemically stain celloidin embedded archival temporal bone tissue of normal individuals with no known otologic disorders other than changes associated with age.

Results

Cells were positively stained throughout the temporal bone within the connective tissue and supporting cells with all three markers. They were often associated with neurons and on occasion entered the sensory cell areas of the auditory and vestibular epithelium.

Conclusions

We have immunohistochemically identified an unappreciated class of cells in the normal adult inner ear consistent in staining characteristics and morphology with macrophages/microglia. As in other organ systems, it is likely these cells play an essential role in organ homeostasis which has not yet been elucidated within the ear.

Introduction

It has been proposed that many otologic disorders including sudden idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss, Meniere’s disease, Cogan’s syndrome, and Susac’s syndrome have an immune mechanism. Previous studies of inner ear immune function have focused primarily on the cellular and humoral immune response of the adaptive immune system. However, our understanding of the innate immune system of the human inner ear, to date, is lacking, and its functional components are unknown.

Resident macrophages have been described in the human middle ear mucosa (1), below the dark cell area of the vestibular system (2), and in the endolymphatic sac (3, 4, 5). However, the remainder of the labyrinth, including the cochlea was once thought of as immuno-privileged. In 1990, data in guinea pigs demonstrated dendritic macrophages phagocytizing degenerating cells and debris in the tunnel of Corti and outer hair cell region (6). Microglial like cells have been observed in the avian inner ear (7). Ma et al. (8) demonstrated bystander injury in guinea pig cochlea associated with local immune response mediated by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes. Within the last decade, data in mouse has emerged demonstrating the existence of both resident cochlear macrophages (9, 10) and the recruitment of inflammatory macrophages (9, 11, 12) to the cochlea. In addition, Zhang et al. (13) have proposed that perivascular resident macrophage-like melanocytes (a hybrid cell type), in the mouse, facilitate fluid homeostasis within the inner ear by controlling the integrity of the intrastrial fluid – blood barrier.

In the central nervous system, microglia are the resident macrophages. So called “resting” microglia have ramified processes and were once considered dormant. In 2005, Nimmerjahn et al. (14), demonstrated that these ramifications constantly assess their microenvironment and proposed that they were performing homeostatic functions such as clearance of accumulated metabolic products and engulfment of tissue components, challenging the hypothesis that microglia with a ramified morphology are “dormant”. Upon “activation”, in response to mechanical or cellular injury, microglia de-ramify and take on a phagocytic amoeboid form. Others have shown that conditions such as chronic stress (15) can lead to microglial hyper-ramification. Focal ischemia reportedly results in a pleomorphic microglial response (16). In the anterior cingulate cortex of human, microglia have been characterized into 4 morphologies: ramified, primed, reactive, and amoeboid (17).

In human cochlear and vestibular tissue, our knowledge of such cells is lacking. Three widely accepted markers for macrophages/microglia that exist as commercially available antibodies and that work in human tissue include CD163, Iba1, and CD68.

CD163 is a scavenger receptor molecule reportedly specific for cells of monocytic lineage including monocytes, macrophages, and microglia (18, 19, 20, 21). CD163 is a transmembrane protein that functions as an endocytic receptor for hemoglobin-haptoglobin complexes (19, 22). CD163 is strongly induced by anti-inflammatory mediators such as glucocorticoids and Interleukin 10 (23, 24). In addition, CD163 has been linked to cytokine production (18) and has been reported to be an innate sensor for bacteria (25).

Iba1 is known as ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1, a specialized calcium binding protein reportedly specific to microglia (26, 27). It is a key participant in membrane ruffling associated with phagocytosis in macrophages and microglia (27). Iba1 has an actin-cross-linking activity believed to be involved in membrane motility and phagocytosis (28). Iba 1 is found in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and podosomes, small multicellular complexes which provide anchorage to extracellular matrix (29).

CD68 is a lysosomal marker (30, 31) and the human homolog of mouse macrosialin, an oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL)-binding protein in mouse macrophages (30) and microglia (32). Macrosialin and CD68 are included in the lamp (lysosomal-associated membrane proteins) family of glycoproteins (33). The location of CD68 as a membrane protein implies a role as the actual scavenger of oxidized LDL or as a component of an antigen-presenting system (33). Recent work on genetic ablation of CD68 in mice resulted in dysfunctional osteoclasts (monocyte origin) with abnormal morphology (34).

The present study utilizes all three of these markers, as well as a marker to α-smooth muscle actin, reportedly NOT present in macrophages/microglia (35), in archival human temporal bone tissue embedded in celloidin from individuals ranging in age from 52 years to 88 years with no known pathology other than the aging process. The antibodies against CD163, Iba1, and CD68 demonstrated an abundant cell class consistent in morphology and protein expression with macrophages/microglia in the human inner ear extending from the apex of the cochlea throughout the labyrinth to the endolymphatic duct and sac. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing this particular population of tissue macrophages in the human inner ear.

Materials and Methods

Sections (20µm) from 7 human celloidin embedded temporal bones from the collection at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary with no history of hearing or balance disorders were used in this study. All 7 specimens were surveyed with all three antibodies at the level of the modiolus. Additionally, in 4 of the 7 cases, serial or semi-serial sections were selected throughout the temporal bones from the superior sections through the inferior sections in order to analyze all pertinent areas of the temporal bone. These sections were also stained with all three antibodies. The number of sections stained from each of the 4 temporal bones was between 27 and 30. In total, 114 sections were stained in this study. The tissue sections were adhered to gelatin coated slides, and the celloidin was removed as previously described (36, 37).

Immunohistochemistry for macrophages was accomplished using a mouse primary antibody against CD163 (Leica Microsystems, United Kingdom) at a dilution of 1:200 to 1:2000, a rabbit primary antibody against Iba1 (Wako chemicals USA, Inc, Richmond, VA) at a dilution of 1:200 to 1:2000, and a mouse primary antibody against CD 68 (DakoCytomation, Denmark) at a dilution of 1:200. In addition, a primary antibody to alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA, Epitomics/Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at a dilution of 1:1000 was utilized to further characterize the macrophages and to rule out fibroblasts. The sections were incubated overnight at room temperature in a humid chamber.

Following primary incubations, sections were rinsed in three washes of PBS. Appropriate secondary antibodies diluted at 1:200 were applied for one hour. The sections were rinsed three times with PBS. Avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase (Standard ABC Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, California) was applied for one hour and rinsed with PBS. Colorization was accomplished with 0.01% diamnobenzidine and 0.01% peroxide (H2O2) for 5 to 10 minutes. To insure that positive immunostaining was not misinterpreted as melanin, present in melanocytes within the stria and modiolus, a purple reaction product was used (VIP, Vector Labs, Burlingame, California) in numerous sections. Sections were rinsed in water, dehydrated, and coverslips were applied.

Results

Immunostaining results are summarized in Table 1 and discussed below

Table 1.

Degree of positive staining by area of inner ear: +++ = consistently present, ++ = present most of the time, + = occasionally/sparsely present, − = absent

| CD163 | Iba1 | CD68 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Along and/or within endosteal boney wall of cochlea | ++ | +++ | + |

| Spiral ligament | +++ | +++ | + |

| StriaVascularis | + | +++ | + |

| Outer Sulcus | + | +++ | + |

| Along wall of Scala Tympani | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Along wall of ScalaVestibuli | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Within Scala Media | − | + | − |

| Along Reissner’s Membrane | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Within Mesenchymal Cells below basilar membrane | ++ | +++ | + |

| Within Organ of Corti | + | + | + |

| Spiral Limbus | + | +++ | + |

| Osseous Spiral Lamina | +++ | +++ | + |

| Around Spiral Ganglion Cells | +++ | +++ | + |

| Modiolus and Eighth Nerve | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Cochlear Aqueduct | +++ | +++ | + |

| Around Scarpa’s Ganglion Cells | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Connective tissue below Saccule | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Connective tissue below utricle | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Connective tissue below 3 semicircular canal ampullae | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Around and/or within endolymphatic duct and sac | + | +++ | + |

The cells that stained positive for the CD163, Iba1, and CD68 antigens had two basic morphologies, either ramified or amoeboid (spheroid), with a continuum of morphologies between the two. All three markers had a tendency to stain the amoeboid morphology more robustly than the ramified morphology. Overall, more cells stained positive with the antibody against Iba1 than with CD163 or CD68. CD68+ immunostaining was seen as punctate staining of lysosomal components in both cell bodies and cell processes of cells with similar morphologies and in similar locations to those described for both the anti-CD163 and anti-Iba1 antibodies. Anti-CD68 staining was distinct yet more difficult to read because it did not fully stain the cell cytoplasm as the anti-Iba1 did. Nonetheless, the CD68+ staining was present in cells similar in morphology and location to both the positive CD163 and Iba1 reaction products.

Spiral Ligament

The CD163+ and Iba1+ macrophages/microglia in the cochlea included those in the spiral ligament among the various types of fibrocytes (figures 1 and 2A–2F). CD68+ staining was sparsely present in the spiral ligament (figure 1C and 1C'). Lysosomes were evident in both ramified and amoeboid cell types in these regions. In addition, Iba1+ cells were embedded into the boney wall of the spiral ligament (figures 1B,1B', 2A, 2B, 2C, and 2D). They extended from the perilymph of the spiral ligament into lacunae and canaliculi of the endosteal layer of the otic capsule (figures 1B, 1B', 2B, 2C, and 2D). Some Iba1+ cells were associated with blood vessels of the spiral ligament. Other staining occurred in the Type II, III, IV, and V fibrocyte regions (38 - fibrocyte classification based on gerbil). There was notably less staining in the Type I fibrocyte area. In tangential sections, Iba1+ cells were seen located in loose connective tissue within the spiral ligament.

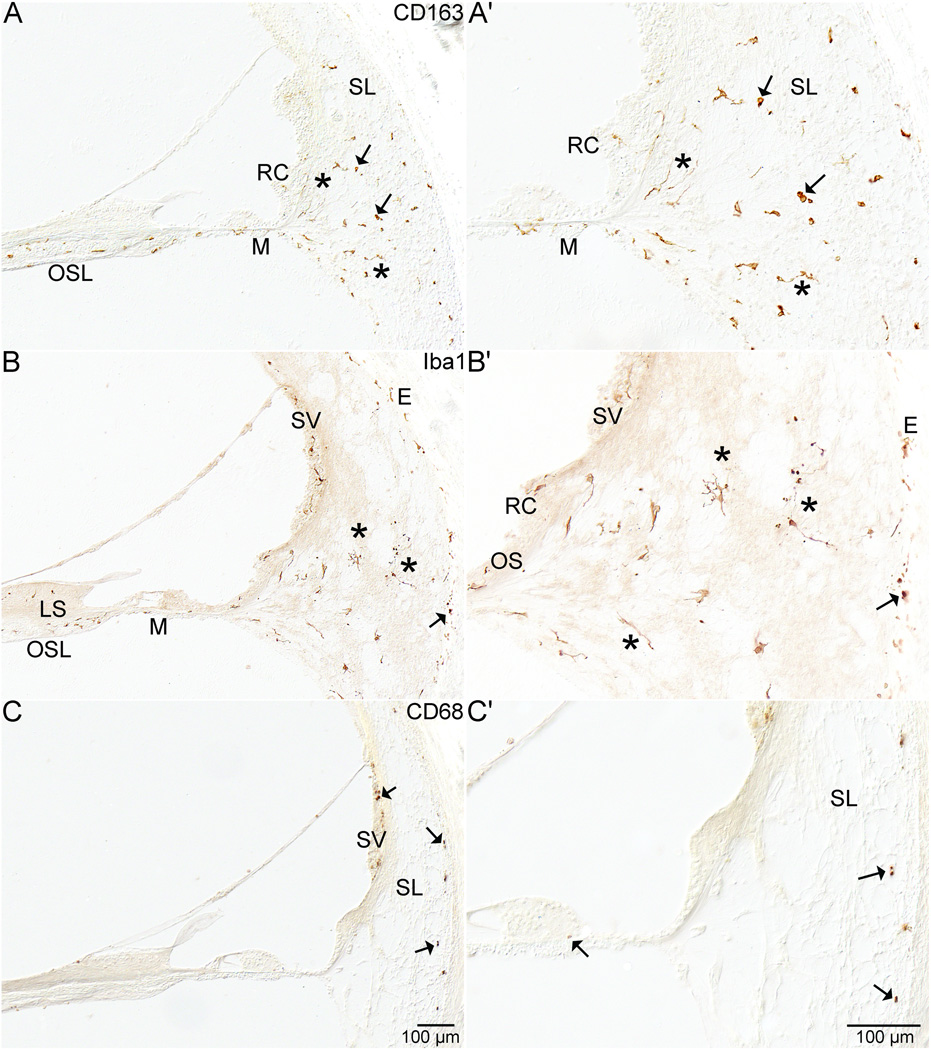

Figure 1. Cochlea.

Figure 1 demonstrates staining in the cochlea with all three antibodies. Figure 1A and 1A' show the anti-CD163 in the lower basal turn of the cochlea in specimen # 1. Both ramified (*) and amoeboid cells (arrow) are demonstrated. Positive staining cells are evident in the osseous spiral lamina (OSL), within the mesenchymal cell layer (M) below the basilar membrane, in the root cells (RC), and throughout the spiral ligament (SL). Figure 1B and 1B' show anti-Iba1 positive staining in the lower basal turn of specimen # 6. Both ramified (*) and amoeboid cells (arrow) are stained. Staining is evident in the osseous spiral lamina (OSL), within the limbus spiralis (LS), in the mesenchymal cell layer (M) below the basilar membrane, in the outer sulcus (OS) and root cell area (RC), within the stria vascularis (SV), and entering the endochondral (E) layer of bone within the otic capsule. Figure 1C and C' show the anti-CD68 staining from the upper basal turn of specimen #7. There was less staining in the spiral ligament with this antibody than with the other two antibodies. Mostly amoeboid staining (arrows) was evident in the spiral ligament (SL) and in the stria vascularis (SV).

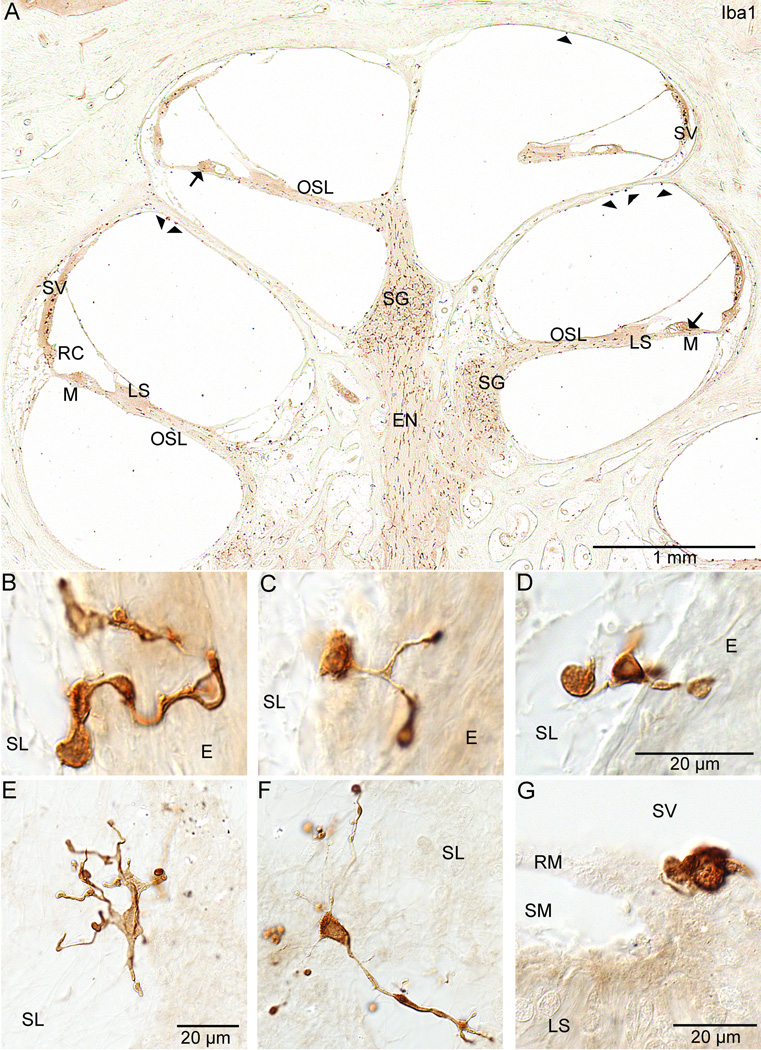

Figure 2. Cochlear staining with anti-Iba1.

Figure 2 shows staining in the cochlea with the antibody against Iba1 only. Figure 2A shows a midmodiolar section through the cochlea of specimen #6. The abundance of staining within the cochlea can be appreciated. Staining can be seen along the eighth nerve (EN) within the modiolus, in Rosenthal's canal within the spiral ganglion (SG), and along the osseous spiral lamina (OSL). Staining is evident in the limbus spiralis (LS) and within the mesenchymal cell layer below the basilar membrane (M). Staining was also present below the cells of Hensen (arrows) in the organ of Corti. Positive staining cells were seen inserting into the outer sulcus and root cell areas (RC). The stria vascularis (SV) also demonstrated positive staining cells within the intermediate cell layer. Positive stained cells (arrowheads) are present in the scala vestibuli along the bone. Figures 2B, 2C (specimen #2), and 2D (specimen #6) show ramified cells in specimens from the spiral ligament area. These cells are partly embedded in the spiral ligament (SL) and partly in the endochondral (E) bone of the otic capsule. Figures 2E and 2F show stained macrophages/microglia from the spiral ligament (SL) of specimen #6 (also visible in figures 1B and 1B'). These cells demonstrate many ramified processes. Figure 2G is also from specimen #6 and demonstrates the amoeboid form of an Iba1 positive staining cell on Reissner's membrane (RM) at its junction with the limbus spiralis (LS). The scala media (SM) and scala vestibuli (SV) are also seen.

Organ of Corti

CD163+, Iba1+, and CD68+ cells occurred along the basilar membrane on the perilymphatic side within the layer of mesenchymal cells (figures 1 and 2), between the epithelial cells of the organ of Corti and within the tunnel of Corti, below the inner hair cells, and at the base of the Hensen cells (figure 2A).

Reissner’s Membrane, Scalae, and Limbus

There were also CD163+, Iba1+, and CD68+ cells staining along Reissner’s membrane (figure 2G) (usually the amoeboid morphology), along the boney wall of scala vestibuli and scala tympani (usually amoeboid morphology) (figure 2A), in the osseous spiral lamina (figures 1 and 2), in the spiral limbus (figure 1B and 2A) both in the area of the fibrocytes, within the interdental cells (figure 2A), and in the vicinity of the attachment of Reissner’s membrane (figure 2G). Positive staining with all three markers was also evident in the area of the outer sulcus and root cells (figures 1 and 2).

Stria Vascularis

The stria vascularis was notable for staining of perivascular cells and cells within the intermediate cell layer (figures 1B, 2A, and 3).

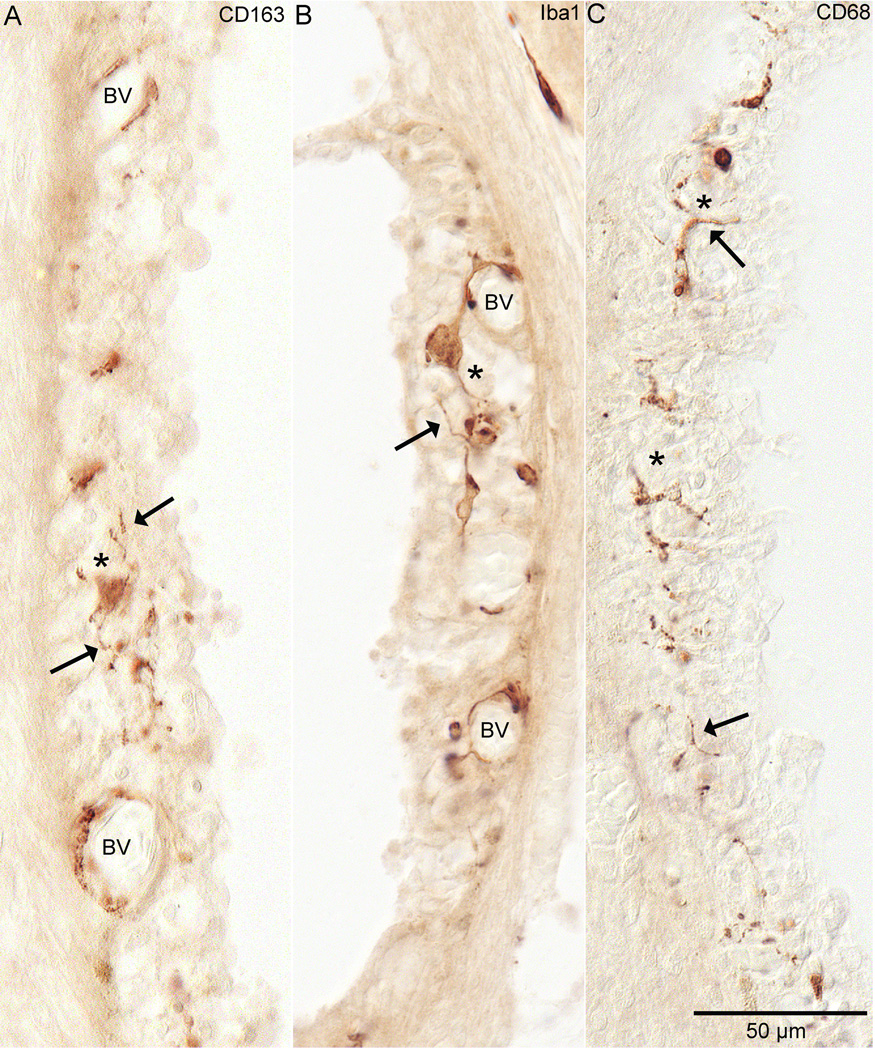

Figure 3. Stria Vascularis.

Staining by all three antibodies was seen in the stria vascularis. In figure 3A, anti-CD163 staining in specimen #6 from the hook region of the cochlea is demonstrated. Note the staining around the blood vessels (BV) and in the middle of the stria (*) in the layer that would contain the intermediate cells. These cells have ramified cell processes (arrow). Figure 3B shows anti-Iba1 staining from the upper middle turn of specimen #2. Very similar staining to CD163 is evident with this antibody. Note the staining around blood vessels (BV) and the staining within the middle of the stria in the intermediate cell layer (*). These cells, like the CD163+ cells, also demonstrate ramified processes (arrow). Figure 3C shows anti-CD68 staining in specimens #2 from the hook region of the cochlea. Note that it is also within the intermediate cell layer. Also note that most of it is occurring in what are cell processes (arrow).

Cochlea, Modiolus, and Ganglion

There were CD163+ staining cells along blood vessels within the inter-scalar septa of the cochlea. There were instances when these cells appeared to be intraluminal while maintaining attachments along the outside of the vessels. These were sometimes in proximity to melanocytes within the modiolus of the cochlea. Cells positive for CD163, Iba1, and CD68 were also seen along the eighth nerve extending from the cochlear apex, and the modiolus, around and among the spiral ganglion cells and extending through the fundus of the internal auditory canal along the length of the nerve (figures 4A, B, and C) and centrally along and through the Schwann-glial junction. CD163+ and Iba1+ cells were seen among Scarpa’s ganglion cells (figure 4A' and B'). Prominent CD68+ staining occurred around spiral ganglion cells and less prominent staining in the area of Scarpa’s ganglion cells (figure 4C and 4C'). The CD68+ staining along the length of the eighth nerve (figure 4C) was robust in most specimens. Sometimes this staining was in association with blood vessels. There were both ramified and amoeboid cells associated with the nerve fibers. Macrophages/microglia staining positive for CD163, Iba1, and CD68 were also present at the round window membrane, along the cochlear aqueduct, and vestibular aqueduct. In some specimens, the CD68+ staining was sparser in the cochlear aqueduct than the CD163+ and Iba1+ staining.

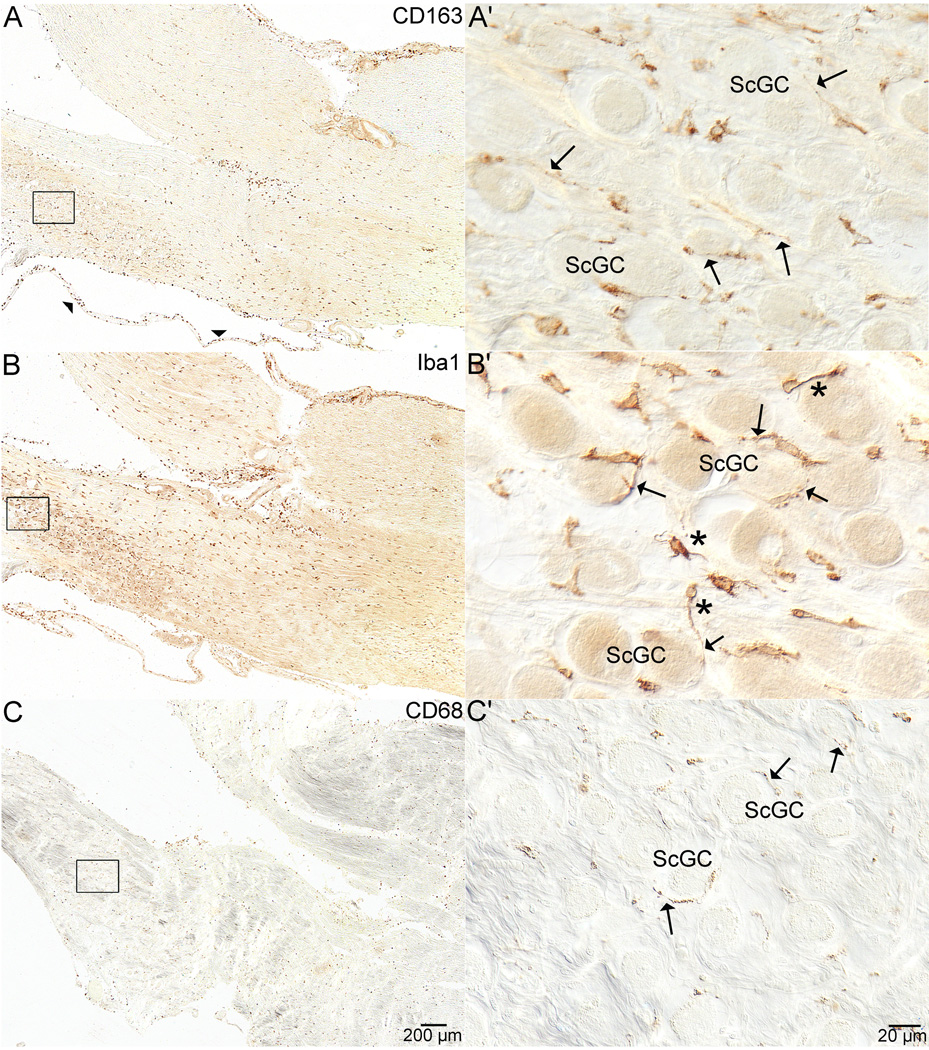

Figure 4. Scarpa’s Ganglion Cells.

Figure 4 shows staining with all three antibodies in the internal auditory canal where the vestibular and auditory portions of the eighth nerve separate from one another near Scarpa’s ganglion. In figure 4A, staining of anti-CD163 from specimen #3 can be seen throughout the eighth nerve and in the peri-neural membrane that surrounds the nerve (arrowheads). Figure 4A' shows higher magnification of boxed area in 4A. The staining is spread throughout the ganglion and occurs in ramified processes (arrows) around Scarpa’s ganglion cells (ScGC). Figure 4B, also from specimen #3, demonstrates anti-Iba1 staining in the same area as in 4A. 4B' shows higher magnification of the anti-Iba1 staining and ramified cells are visible (*). Additionally, stained cell processes of the macrophages\microglia (arrows) are seen encircling the ganglion cells (ScGC). Figure 4C shows staining with the anti-CD68 antibody from specimen #2. The staining in the nerve and around Scarpa’s ganglion was not as prominent as with the other two antibodies, but was still present throughout the eighth nerve (4C). Stained cell processes of the macrophages\microglia (arrows) are seen encircling the ganglion cells (ScGC in 4 C').

Saccule, Utricle, and Semicircular Canal Ampullae

Macrophages/microglia staining positive for CD163 and Iba1were evident in the connective tissue below the saccule, utricle, and all three ampullae of the semicircular canals. Iba1 positive cells were also evident in the reinforced area of the saccular membrane. CD68+ staining was seen within the connective tissue below the saccule and utricle. There was sparse CD68+ staining within the connective tissue below the sensory epithelia of the 3 semicircular canals.

Endolymphatic Duct and Sac

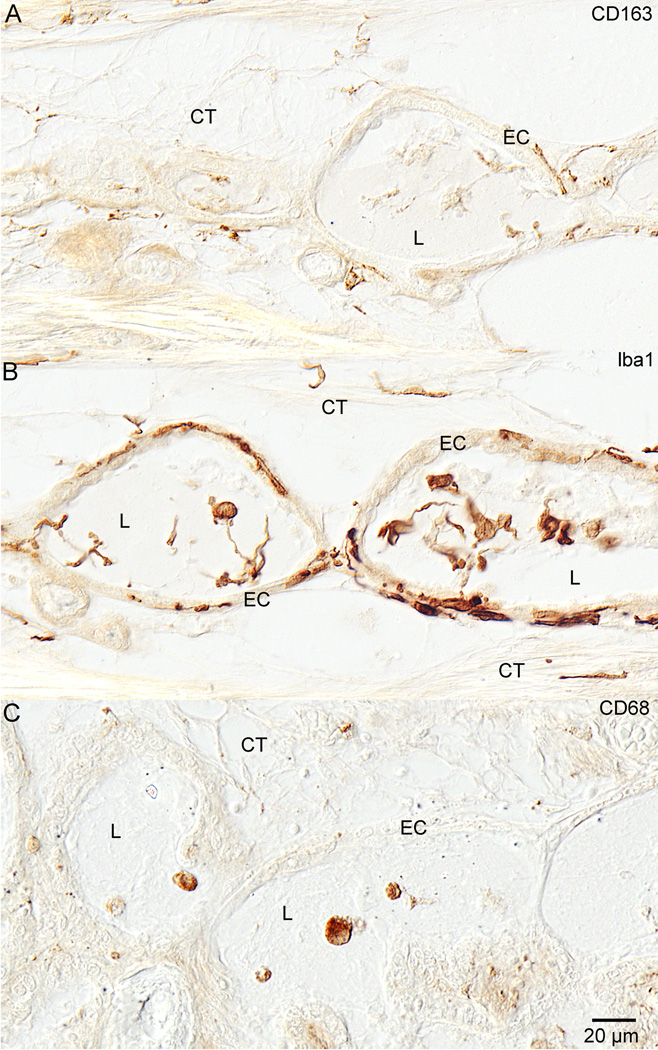

Macrophages/microglia staining positive for CD163 (figure 5A) and Iba1 (figure 5B) were present in the endolymphatic duct connective tissue, within the epithelial cells of the duct, and within the duct lumen. There appeared to be more CD68+ staining (figure 5C) within the lumen of the endolymphatic duct and sac than within the connective tissue subjacent to the epithelial lining in most specimens.

Figure 5. Endolymphatic Duct.

Figure 5 shows staining with all three antibodies in the distal endolymphatic duct. Figure 5A shows anti-CD163 staining in the endolymphatic duct of specimen #6. Positive staining was seen in the connective tissue (CT) around the duct as well as in the epithelial cells (EC) of the duct and in the duct lumen (L) as well. There were both round and ramified cells that stained. Figure 4B shows anti-Iba1 staining in the endolymphatic duct of specimen #6. There is plentiful staining in all of the same locations as with the anti-CD163. Staining was seen in the connective tissue (CT), epithelial cells (EC), and within the lumen (L). Figure 5C demonstrates anti-CD68 staining in the endolymphatic duct of specimen #2. The most prominent staining here was in round cells within the lumen (L) of the duct.

α-SMA+

The cells staining positive for α-smooth muscle actin included the smooth muscle cells of the carotid artery, the smooth muscle cells of the arterioles in the modiolus and the eighth nerve, the cuticular plate and stereocilia of both the inner and outer hair cells, cells beneath the basal cells of the stria vascularis, and the arterioles of the middle ear mucosa. The α-SMA antibody did not stain the same cell class as the CD163, Iba1, or CD68 antibodies, suggesting that these cells are not fibroblasts.

Discussion

Macrophages/microglia play a critical role in inflammation. They are capable of secreting cytokines, both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory and thereby play a critical role in innate immunity and during an immune response. They present antigen, activate the adaptive immune system, and assist in resolution of inflammation. These cells with their long arborizing processes actively communicate with cells in their surrounding milieu and play a critical role in tissue homeostasis.

We have no proof that all of the cells described here are “resident” as opposed to infiltrating macrophages. Nonetheless, all of our staining for CD163, Iba1, and CD68 is consistent with a class of cells integral to the innate immune system. The finding that they are present in such abundance in ears with no known otologic pathology suggests an important role in cochlear physiology and pathophysiology.

It appears that there is a very complex immune surveillance system at work monitoring and defending the human inner ear. There do not appear to be any completely “immune-privileged” sites within the ear. The soft tissue of the inner ear is well populated by these cells. Cells within the sensory epithelia are not as commonly stained, but macrophages are present occasionally in both the auditory and vestibular epithelium. The perilymphatic fluid spaces of the cochlea (scala tympani and scala vestibuli) are commonly inhabited by macrophages particularly those with amoeboid morphology. It appears that each microenvironment of the inner ear possesses unique phenotypic nuances in macrophages/microglia expression. Macrophages are known to be phenotypically heterogeneous (39). All areas, including the stria, spiral ligament, basilar membrane, neurons of the 8th nerve may require slightly varied functions of the macrophages/microglia in the normal state. Following various pathologies and trauma, macrophages/microglia may change their expression of markers, activation state, and cell shape. For example, in the brain, it has been shown that CD163 is up regulated within hours after anoxia, hypoxia, and hemorrhage (21).

The macrophages described in the present study around the vessels of the stria vascularis may be similar to those described in mouse by Zhang et al. (13), who termed them “perivascular-resident macrophage-like melanocytes (PVM/Ms)”. PVM/Ms are integral to the intrastrial fluid-blood barrier and necessary for normal hearing. Zhang et al. (13) found that these cells were partly responsible for controlling the permeability of the endothelium by maintaining tight junctions and adhesion proteins of strial capillaries. Perhaps these particular cells play a role in the strial swelling seen after acoustic trauma (11) and following antibiotic or diuretic exposure (12). An alternate interpretation of the PVM/Ms could be that macrophages/microglia present in the stria may ingest pigmented cells resulting in melanin within phagosomes of macrophages. Such phagosomes may retain epitopes of the ingested cells. Further characterization in both mouse and human is needed.

The human spiral ligament appears to be fairly well populated by macrophages/microglia. It is intriguing that our staining showed macrophages/microglia to be present throughout the spiral ligament as well as juxtaposed to, or surrounding blood vessels in the ligament. These cells were often seen in the area of the Type II, III, IV, and V fibrocytes. Although sometimes present near Type I fibrocytes of the spiral ligament near vessels, they rarely appeared intermingled among the Type I fibrocytes themselves. It is interesting to note that Type I fibrocytes, in human, have been found to stain positively for NFκ B, a set of transcription factors involved in the production of inflammatory cytokines (40).

The macrophages/microglia in this study were seen inserting processes into the endosteal layer of the cochlea. This may implicate them in homeostasis of the otic capsule similar to the homeostatic and trophic roles played by resident macrophages in osteal tissue described as OsteoMacs (41). These authors also claimed that OsteoMacs are lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-responsive cells within osteal tissues. These findings in bone suggest a possible role for macrophages at the otic capsule/fluid space boundaries of the cochlea and in such disorders as otosclerosis (42).

We know from studies on macrophages/microglia in the central nervous system (CNS), that they are involved in axonal homeostasis, cleaning of cellular debris, and recognition of bacteria and viruses. Those described in this study may play similar roles in development and removal of dead and dying cells in the organ of Corti both during aging and trauma as described in guinea pigs (6) and following aminoglycoside ototoxicity in rats (43).

Within the CNS, microglia are believed to modulate synaptic density and activity. It would be interesting to know if there exists a similar relationship in the ear as reported in the CNS, at synapses, where microglia have been described as using the complement branch of the immune system to perform synaptic pruning (44). Macrophages play a role in responses to acoustic trauma in the mouse (9, 11) and most likely will in human ears as well. In 2005, Yagihashi et al. (45), demonstrated that administration of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) could protect spiral ganglion neurons in a rat model of auditory nerve injury. These authors pointed out that there exists the potential for neurotoxicity as well as neuro-protection depending on activation status of the macrophages/microglia.

We are only beginning to understand the role of macrophages/microglia in degenerative disorders of the CNS including Alzheimer’s disease, ALS, MS, and Parkinson’s disease (46, 47). Our finding that the 7th and 8th cranial nerves are heavily populated by macrophages/microglia gives us some idea about their importance, utility, and influence on the neural tissue of the inner ear as well. Microglia are known to signal neurons and vice versa. Most of the receptors on the surface of microglia such as cytokine receptors, chemokine receptors, scavenger receptors, and pattern recognition receptors bind ligands that are secreted, or expressed on membranes of healthy neurons (48). In the presence of inflammatory signals, these microglial receptors are activated resulting in “resting” microglia transitioning to “activated” motile effector cells. The activated microglia are capable of contributing to ongoing inflammation (48). This has enormous implications given their placement throughout the labyrinth and the role they may be playing in both health and pathology of balance and hearing.

We can expect the cells described here to communicate with cells of the adaptive immune system. They may have a role in otologic disorders such as idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss and endolymphatic hydrops. In addition, we know they play a role in response to cochlear implantation (49). It will be important to further characterize these cells and their individual expressions in all of these disorders.

This study provides an overview of the abundance of and location of macrophages/microglia in the presumed normal human inner ear. Their roles in cochlear physiology and disease need to be elucidated. This may lead to a better understanding of many otologic disorders and suggest better forms of treatment.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Diane Jones, Barbara Burgess, and MengYu Zhu for their careful, thoughtful, and expert preparation of the temporal bone specimens utilized in this study. And many thanks to Dr. Anat Stemmer-Rachamimov, M.D. for her consultations, slide reviews, and suggestions of antibodies. Thanks to our temporal bone donors whose gifts are so very precious and integral to our research and understanding of otologic disorders. And we are very grateful for the continued financial support of the NIDCD.

This work was supported by NIDCD grant # U24DC011943

Footnotes

There are no declared conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lim DJ. Functional morphology of the mucosa of the middle ear and eustachian tube. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85(2 Suppl 25 Pt 2):36–43. doi: 10.1177/00034894760850S209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masuda M, Yamazaki K, Kanzaki J, Hosoda Y. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural investigation of the human vestibular dark cell area: roles of subepithelial capillaries and T lymphocyte-melanophage interaction in an immune surveillance system. Anat Rec. 1997;249(2):153–162. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199710)249:2<153::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altermatt HJ, Gebbers JO, Muller C, Arnold W, Laissue JA. Human endolymphatic sac: evidence for a role in inner ear immune defence. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1990;52(3):143–148. doi: 10.1159/000276124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rask-Andersen H, Danckwardt-Lillieström N, Friberg U, House W. Lymphocyte-macrophage activity in the human endolymphatic sac. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1991;485:15–17. doi: 10.3109/00016489109128039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansson B, Rask-Andersen H. Osmotically induced macrophage activity in the endolymphatic sac. On the possible interaction between periaqueductal bone marrow cells and the endolymphatic sac. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1992;54(4):191–197. doi: 10.1159/000276297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fredelius L, Rask-Andersen H. The role of macrophages in the disposal of degeneration products within the organ of Corti after acoustic overstimulation. Acta Otolaryngol. 1990;109(1–2):76–82. doi: 10.3109/00016489009107417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhave SA, Oesterle EC, Coltrera MD. Macrophage and microglia-like cells in the avian inner ear. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398(2):241–256. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980824)398:2<241::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma C, Billings P, Harris JP, Keithley EM. Characterization of an experimentally induced inner ear immune response. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(3 Pt 1):451–456. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200003000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirose K, Discolo CM, Keasler JR, Ransohoff R. Mononuclear phagocytes migrate into the murine cochlea after acoustic trauma. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489(2):180–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okano T, Nakagawa T, Kita T, Kada S, Yoshimoto M, Nakahata T, Ito J. Bone marrow-derived cells expressing Iba1 are constitutively present as resident tissue macrophages in the mouse cochlea. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1758–1767. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tornabene SV, Sato K, Pham L, Billings P, Keithley EM. Immunecellrecruitmentfollowingacoustictrauma. Hear Res. 2006 Dec;222(1–2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirose K, Li SZ, Ohlemiller KK, Ransohoff RM. Systemic lipopolysaccharide induces cochlear inflammation and exacerbates the synergistic ototoxicity of kanamycin and furosemide. JARO. 2014;15:555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10162-014-0458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Dai M, Fridberger A, Hassan A, DeGagne J, Neng L, Zhang F, He W, Ren T, Trune D, Auer M, Shi X. Perivascular-resident macrophage-like melanocytes in the inner ear are essential for the integrity of the intrastrial fluid-blood barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(26):10388–10393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205210109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinwood M, Tynan RJ, Charnley JL, Beynon SB, Day TA, Walker FR. Chronic stress induced remodeling of the prefrontal cortex: structural re-organization of microglia and the inhibitory effect of minocycline. Cerebral Cortex. 2013;23:1784–1797. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison HW, Filosa JA. A quantitative spatiotemporal analysis of microglia morphology during ischemic stroke and reperfusion. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10(4):1–20. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres-Platas SG, Comeau S, Rachalski A, Dal Bo G, Cruceanu C, Turecki G, Giros B, Mechawar N. Morphometric characterization of microglial phenotypes in human cerebral cortex. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van den Heuvel MM, Tensen CP, van As JH, Van den Berg TK, Fluitsma DM, Dijkstra CD, Döpp EA, Droste A, Van Gaalen FA, Sorg C, Högger P, Beelen RHJ. Regulation of CD163 on human macrophages: cross-linking of CD163 induces signaling and activation. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:858–866. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristiansen M, Graversen JH, Jacobsen C, Sonne O, Hoffman HJ, Law SKA, Moestrup SK. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature. 2001;409:198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen TT, Schwartz EJ, West RB, Warnke RA, Arber DA, Natkunam Y. Expression of CD163 (hemoglobin scavenger receptor) in normal tissues, lymphomas, carcinomas, and sarcomas is largely restricted to the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(5):617–624. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000157940.80538.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holfelder K, Schittenhelm J, Trautmann K, Haybaeck J, Meyermann R, Beschorner R. De novo expression of the hemoglobin scavenger receptor CD163 by activated microglia is not associated with hemorrhages in human brain lesions. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:1007–1017. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abraham NG, Drummond G. CD163-mediated hemoglobin-heme uptake activates macrophage HO-1, providing an antiinflammatory function. Circ Res. 2006;99:911–914. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000249616.10603.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sulahian TH, Högger P, Wahner AE, Wardwell K, Goulding NJ, Sorg C, Droste A, Stehling M, Wallace PK, Morganelli PM, Guyre PM. Human monocytes express CD163, which is upregulated by IL-10 and identical to p155. Cytokine. 2000;12(9):1312–1321. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kowal K, Silver R, Sławińska E, Bielecki M, Chyczewski L, Kowal-Bielecka O. CD163 and its role in inflammation. Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica. 2011;49(3):365–374. doi: 10.5603/fhc.2011.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabriek BO, van Bruggen R, Deng DM, Ligtenberg AJM, Nazmi K, Schornagel K, Vloet RPM, Dijkstra CD, van den Berg TK. The macrophage scavenger receptor CD163 functions as an innate immune sensor for bacteria. Blood. 2009;113(4):887–892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-167064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imai Y, Ibata I, Ito D, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatability complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:855–862. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohsawa K, Imai Y, Kanazawa H, Sasaki Y, Kohsaka S. Involvement of Iba1 in membrane ruffling and phagocytosis of macrophages/microglia. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3073–3084. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki Y, Ohsawa K, Kanazawa H, Kohsaka S, Imai Y. Iba1 is an actin-cross-linking protein in macrophages/microglia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:292–297. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siddiqui TA, Lively S, Vincent C, Schlichter LC. Regulation of podosome formation, microglial migration and invasion by Ca2+-signaling molecules expressed in podosomes. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9(250):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramprasad MP, Terpstra V, Kondratenko N, Quehenberger O. Cell surface expression of mouse macrosialin and human CD68 and their role as macrophage receptors for oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:14833–14838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Z, Shih DM, Xia YR, Lusis AJ, de Beer FC, de Villiers WJS, van der Westhuyzen DR, deBeer MC. Structure, organization, and chromosomal mapping of the gene encoding macrosialin, a macrophage-restricted protein. Genomics. 1998;50:199–205. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graeber MB, Streit WJ, Kiefer R, Schoen SW, Kreutzberg GW. New expression of myelomonocytic antigens by microglia and perivascular cells following lethal motor neuron injury. J Neuroimmunol. 1990;27:121–132. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90061-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurushima H, Ramprasad N, Kondratenko N, Foster DM, Quehenberger O, Steinberg D. Surface expression and rapid internalization of macrosialin (mouse CD68) on elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:104–108. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashley JW, Zhenqi S, Zhao H, Xingsheng L, Kesterson RA, Feng X. Genetic ablation of CD68 results in mice with increased bone and dysfunctional osteoclasts. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ. Microglia, macrophages, perivascular macrophages, and pericytes: a review of function and identification. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(3):388–397. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0303114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Malley JT, Burgess BJ, Jones DD, Adams JC, Merchant SN. Techniques of celloidin removal from temporal bone sections. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009 Jun;118(6):435–441. doi: 10.1177/000348940911800606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Malley JT, Merchant SN, Burgess BJ, Jones DD, Adams JC. Effects of fixative and embedding medium on morphology and immunostaining of the cochlea. Audiol Neurootol. 2009;14(2):78–87. doi: 10.1159/000158536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spicer SS, Schulte BA. Spiral ligament pathology in quiet-aged gerbils. Hear Res. 2002;172(1–2):172–185. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olah M, Biber K, Vinet J, Boddeke HW. Microglia phenotype diversity. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10(1):108–118. doi: 10.2174/187152711794488575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams JC. Clinical implications of inflammatory cytokines in the cochlea: a technical note. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:316–322. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200205000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang MK, Raggatt LJ, Alexander KA, Kuliwaba JS, Fazzalari NL, Schroder K, Maylin ER, Ripoll VM, Hume DA, Pettit AR. Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:1232–1244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenna MJ, Merchant SN. Disorders of Bone. In: Merchant SN, Nadol JB, editors. Schuknecht’s Pathology of the Ear. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2010. pp. 728–732. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Li H. Microglia-like cells in rat organ of Corti following aminoglycoside ototoxicity. NeuroReport. 2000;11:1389–1393. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200005150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schafer DP, Lehman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, Ransohoff RM, Greenberg ME, Barres BA, Stevens B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74(4):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yagihashi A, Sekiya T, Suzuki S. Macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) protects spiral ganglion neurons following auditory nerve injury: morphological and functional evidence. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doens D, Fernández PL. Microglia receptors and their implications in the response to amyloid β for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11(48):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu R, Shen Q, Xu P, Luo JJ. Phagocytosis of microglia in the central nervous system diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:1422–1434. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kierdorf K, Prinz M. Factors Regulating Microglia Activation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nadol JB, O’Malley JT, Burgess BJ, Galler D. Cellular immunologic responses to cochlear implantation in the human. Hear Res. 2014;318:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]