Abstract

Background

Pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance are prevalent and distressing symptoms in persons with advanced heart failure. Although many lifestyle and self-care interventions have been developed to control heart failure progression, very few studies have explored treatments exclusively for symptom palliation. Cognitive-behavioral strategies may be effective treatment for these symptoms in advanced heart failure.

Objective

A systemic review was conducted to describe the effect of cognitive-behavioral strategies on pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in patients with heart failure.

Methods

CINAHL, Medline, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through December 2014. Articles were selected for inclusion if they tested a cognitive-behavioral strategy using a quasi-experimental or experimental design, involved a sample of adults with heart failure, and measured pain, dyspnea, fatigue, sleep disturbance, or symptom-related quality of life (QoL). The two authors evaluated study quality, abstracted data elements from each study, and synthesized findings.

Results

Thirteen articles describing nine unique studies met criteria and were included in the review. Five studies tested relaxation strategies, three tested meditation strategies, and one tested a guided imagery strategy. Seven of the nine studies demonstrated some improvement in symptom outcomes. Relaxation, meditation, guided imagery, or combinations of these strategies resulted in less dyspnea and better sleep compared to attention control or usual care conditions, and reduced pain, dyspnea, fatigue and sleep disturbance within treatment groups (pre- to post-treatment). Symptom-related QoL was improved with meditation compared to attention control and usual care conditions, and improved pre- to post-guided imagery.

Conclusions

Studies exploring cognitive-behavioral symptom management strategies in heart failure vary in quality and report mixed findings, but indicate potential beneficial effects of relaxation, meditation, and guided imagery on heart failure-related symptoms. Future research should test cognitive-behavioral strategies in rigorously designed efficacy trials, using samples selected for their symptom experience, and measure pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance outcomes with targeted symptom measures.

Keywords: Heart failure, Symptoms, Relaxation, Meditation, Imagery

Introduction

Heart failure is a growing health problem in the US, affecting over 5 million people with numbers expected to increase substantially over the next 15 years.1,2 Severe and distressing symptoms accompany heart failure, particularly for patients with advanced disease. Prevalent symptoms include pain (49–71%), dyspnea (56–86%), fatigue (76–84%) and sleep disturbance (38–64%).3–8 These symptoms are often rated as moderate or severe in intensity, and over 75% of patients describe the experience as quite a bit or very bothersome.4,5,7 Unrelieved symptoms contribute to diminished functional status, frequent hospitalizations, and poor quality of life.3,6,9–11 Although many lifestyle and self-care interventions have been developed to manage day-to-day treatment regimens and limit disease progression, surprisingly little research has focused exclusively on symptom palliation in advanced heart failure, when the disease may become refractory to usual medical management.

The American College of Cardiology Foundation / American Heart Association guidelines for the management of heart failure identify the need to assess pain, dyspnea, and fatigue as indicators of ischemia, and emphasize the need for palliative care including ongoing symptom control, yet provide no specific recommendations for symptom management strategies.12 The problems of sleep disturbance and other types of non-cardiac pain are overlooked, despite their widespread prevalence.13 Treatments for pain in heart failure may involve the use of acetaminophen for mild pain, opioids for moderate to severe pain, and adjuvant medications such as antidepressants, local anesthetics or topical analgesics.14–16 Dyspnea in heart failure may be treated with diuretics, positioning, exercise rehabilitation, and may also be responsive to opioids.17–20 Fatigue has few treatment options, but heart failure practitioners may recommend balancing activity with rest, participating in exercise, and use of appetite stimulants and nutritional supplementation.17,20,21 Sleep disturbance in heart failure may be managed with hypnotics, anxiolytics, melatonin receptor agonists, antihistamines, sleep hygiene, or treatment of underlying sleep apnea.13,18,20

While pharmacologic interventions are often perceived as the most convenient methods of symptom palliation, medications alone are generally not sufficient to produce adequate symptom relief, and some medications may be contraindicated in heart failure. For example, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents commonly used for mild to moderate pain, particularly musculoskeletal pain, are not recommended in patients with heart failure due to increased risk of renal toxicity.14,15 In heart failure, as well as other chronic conditions (e.g., cancer, asthma, arthritis), management of somatic symptoms is often achieved or optimized through the use non-pharmacologic interventions.22–23 Non-pharmacologic interventions can include physical modalities (e.g., topical heat / cold application, massage, acupuncture, exercise), psychological modalities (e.g., psychotherapy, support groups, cognitive-behavioral strategies), as well as alternative therapies (e.g., energy therapies, dietary practices, homeopathy).

Cognitive-behavioral strategies, a type of psychological modality, may be particularly appealing as they target anxiety and distress, shared components of many heart failure-related symptoms, particularly pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance.24–25 Anxiety may contribute to the development and perception of these symptoms and enhance their intensity and associated distress.26 Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a type of psychological therapy, delivered over multiple weeks in individual or group format including (1) education about how one’s thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors affect the perceived symptom experience, (2) training in various coping skills to change thoughts and behaviors, and (3) adoption and maintenance of those skills through structured practice and feedback.27 Several of the cognitive-behavioral strategies used as components of CBT have beneficial effects when applied as single strategies, outside of the “therapy” context. For example, relaxation, guided imagery, and distraction strategies have been found to reduce pain28–32, dyspnea23,33–34, fatigue35–36, and sleep disturbance37–39 in various health conditions. Recent research has demonstrated initial efficacy of these strategies across clustered symptoms, including co-occurring pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in patients with advanced cancer.40

Cognitive-behavioral strategies may be appropriate and highly effective for palliation of pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance, occurring alone or concurrently, in patients with advanced heart failure, but current evidence has not been systematically reviewed. The purpose of this paper is to review studies of cognitive-behavioral strategies for management of four common symptoms in heart failure. A systemic review was conducted to answer the PICO question, In patients with heart failure, what is the effect of relaxation, meditation, guided imagery, and attention distraction strategies on pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance? The four cognitive-behavioral strategies were chosen for this review because they require little specialized training and can be delivered by a broad range of healthcare professionals, they are widely accessible, and easily amenable for self-care among patients with limited functional capacity. Exercise-based strategies (e.g., yoga, Tai Chi), which require more training and supervision and draw on physical as well as cognitive-behavioral mechanisms, were excluded from this review.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Process

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) recommendations were followed in reporting this review.41 Duplicate review of abstracts, study quality ratings, and data extraction were conducted to assure thorough and unbiased collection of data. The databases CINAHL, Medline, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through December 2014. The following search terms were used in combination with “heart failure”: “nonpharmacologic”, “distraction”, “guided imagery”, “relaxation therapy”, “cognitive-behavioral”, “meditation”, “mindfulness”, and “coping skills”. Limits set on the search included English language; academic journal or dissertation / thesis; and research article (CINAHL), clinical trial (PubMed), or empirical study (PsychINFO). Reference lists of systematic reviews identified in this search, as well as the reference lists of articles selected for inclusion in the review were searched to identify other relevant studies.

All abstracts were reviewed by the investigators to exclude those that did not test a cognitive-behavioral strategy in the context of heart failure. Copies of the publications were obtained for all abstracts not excluded. Both investigators reviewed the full-text article and recommended inclusion if the study met the following criteria.

Reported results of a study that tested a cognitive-behavioral strategy or therapy that included cognitive-behavioral strategies as components.

Used a quasi-experimental or experimental design. Case studies were excluded.

Involved a sample of adults with heart failure.

Measured symptoms of pain, dyspnea, fatigue, or sleep disturbance, or reported symptom-related quality of life (QoL) (e.g., QoL subscale score composed largely of symptom items). Studies were excluded if they only reported overall QoL score and not specific symptom items or symptom-related subscale score.

Disagreements were resolved by jointly comparing the abstract or publication against eligibility criteria and discussing them until consensus was reached.

Evaluation of Study Quality

Both authors (KK, LB) independently evaluated the risk of bias using Yates and colleagues’ quality rating scale for studies of psychological interventions for pain.42 Yates’ rating scale was selected over more general study quality scales as a more rigorous standard for evaluating the validity of findings from trials of cognitive-behavioral symptom management strategies (i.e., psychological interventions). The Yates’ scale addresses a greater range of characteristics related to validity of psychological intervention trials compared to drug or device trials and is specific to subjective symptom outcomes. Quality assessment items regarding outcome measures are relevant to any symptom, and are not pain specific (e.g., the authors report the measure’s reliability and sensitivity to change).

Yates’ scale calls for assessment of treatment quality and quality of the study design and methods. Six items are used to determine treatment quality including assessments of treatment rationale, duration, manualization, therapist training, and patient engagement. Twenty items are used to assess quality of study design and methods comprising inclusion/exclusion criteria, attrition, sample and group characteristics, well-matched control condition, randomization and allocation, data collection, outcome measures, assessment of sustained change, and statistical analyses. Treatment and study characteristics are rated on a 0–2 scale as “adequate” (2), “partially adequate” (1) or “inadequate” (0). For some items, partially adequate is not a logical option and items are scored as “adequate” (1) or “inadequate (0). Item ratings are summed to create an overall quality score ranging from 0 to 35, with higher scores indicating better quality.

For the purposes of this review, the authors considered the cognitive-behavioral strategy as the treatment of interest (e.g., even when the cognitive-behavioral strategy was considered the “active control” or comparison condition in testing another treatment), and symptoms as the outcome of interest. Where two or more publications reported different aspects of the same study, only one quality evaluation was conducted for the study. A minor modification was made to one item for this review. The Yates item related to follow-up assesses whether researchers have attempted to measure sustainable change between treatment and control groups and provides 6-months as an example, based on their clinical population focus. Based on our (LCB) experience with the heart failure population and the known instability of the disease process and increased mortality among end-stage heart failure patients, we designated 3-months as a measure of adequate follow-up. The two authors met to compare item scores and discuss their evaluations; disagreements were resolved by jointly reviewing the source documents until consensus was reached.

Data collection and analysis

We developed general procedures for evaluation and data abstraction, but did not publish a detailed review protocol given the limited number of publications and the early stage of research on palliative strategies for heart failure. We developed a data extraction table, pilot-tested it on two studies, and made adjustments, as necessary. The following data elements were abstracted from each study in duplicate, by the two authors: study purpose, design, sample inclusion and exclusion criteria (with emphasis on any heart failure or symptom eligibility criteria), symptom and/or quality of life measures, treatment characteristics (training format, mode of delivery, frequency, duration), length of study follow-up, and findings regarding symptom outcomes. Study authors were not contacted to obtain further data beyond that available in the published article. Data extraction tables were compared and disagreements were resolved through discussion and joint review of the source document.

Results

Results of Search

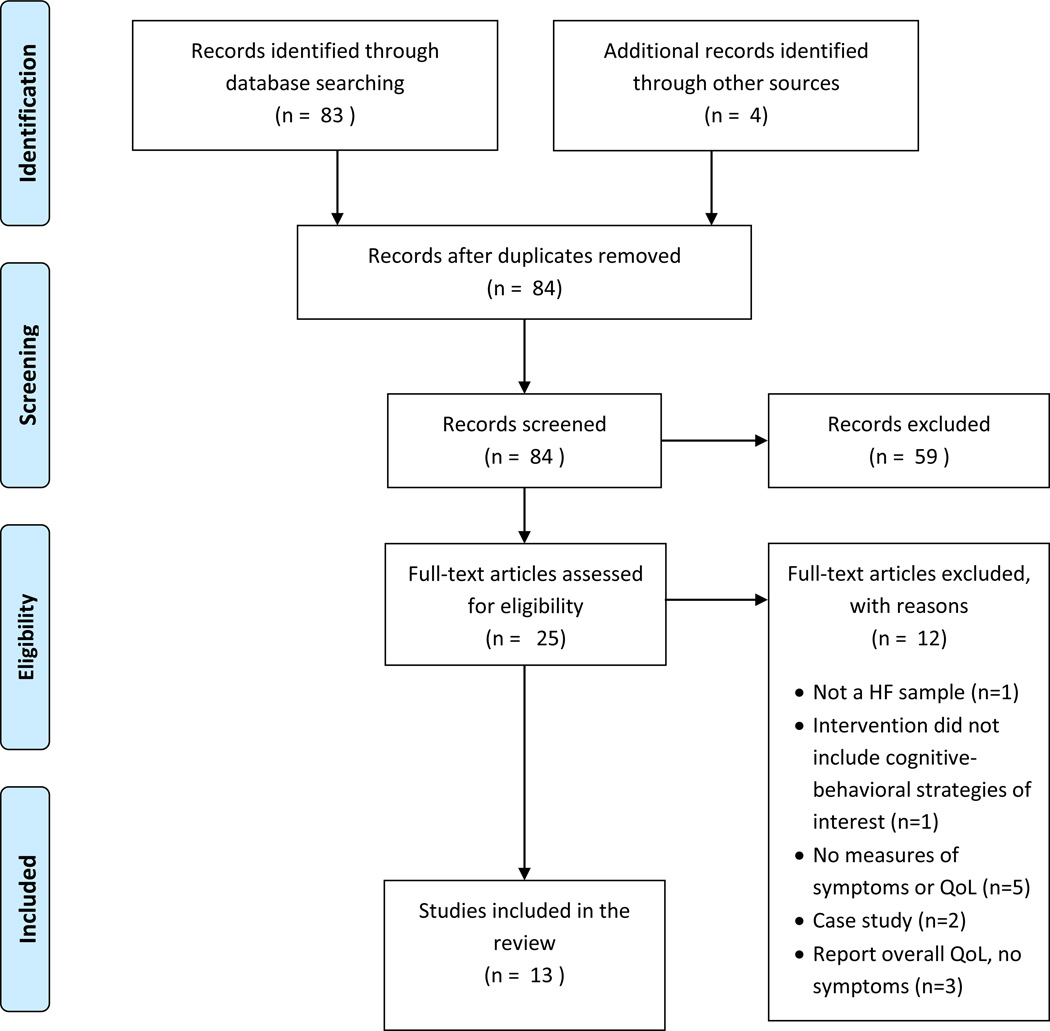

A total of 83 articles were identified through the database search. The reference lists of three systematic reviews of cognitive-behavioral strategies for depression in heart failure were searched.43–45 An additional 4 articles were identified through searching these and reference lists of the included studies. Thirteen articles describing findings of 9 unique studies met criteria and were included in the review. A PRISMA flow diagram outlining the search results is presented in Figure 1. Five studies used relaxation strategies46–47, 51–52, 54–56, 58, three used meditation strategies50, 53, 57, one used a guided imagery strategy48–49, and none used simple attention diversion (distraction) as a stand-alone intervention. Study quality scores ranged from 9 to 24 out of 35 possible points, with higher scores indicative of better quality and less risk of bias (Table 1).42 Characteristics of each study are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Quality ratings of reviewed studies

| Author, publication year | Quality rating |

|---|---|

| Beniaminovitz et al., 200249; Klaus et al., 200048 | 9 |

| Chang, et al., 200446 & 200547 | 20 |

| Cully et al., 201058 | 19 |

| Curiati et al., 200553 | 16 |

| Javadeyappa et al., 200750 | 21 |

| Sullivan et al., 200957 | 16 |

| Swanson et al., 200952 | 24 |

| Wang et al., 201351 | 19 |

| Yu et al., 200754, 200756, 201055 | 23 |

Potential range of quality scores = 0 – 35; higher scores indicate better quality.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies Reviewed

| Author | Sample | N | Treatment | Length / Frequency of Practice |

Symptom and Quality of Life Measures |

Timing | Results related to Relaxation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relaxation | |||||||

| Chang et al., 200547 Chang et al., 200446 |

Adults with Class II–III HF | 95 (57) |

|

90-minute training session, once/week × 15 weeks plus 15–20 minutes twice daily home practice sessions |

Symptoms Self-report comments from a subsample of 57 participants QoL MLWHFQ – physical subscale |

|

Between Groups

|

| Cully et al., 201058 | Adults with CHF and/or COPD with ≥ mild functional impact and concurrent depression or anxiety | 23 |

|

50-minute sessions, once/week × 6 weeks plus 10–15 minute booster phone calls × 3 at 8-, 10-, and 12-weeks |

Symptoms Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire |

|

Within Group

|

| Swanson et al., 200952 | Adults with Class I-III HF | 35 |

|

45-minute training sessions, once / week × 6 weeks plus 20-minute daily home practice sessions |

Symptoms Dyspnea – Borg scale Fatigue – Borg scale QoLMLWHFQ – physical subscale |

|

Between Groups

|

| Yu et al., (200754, 200756, 201055) | Adults with HF, admitted to the hospital | 153 |

|

60-minute training sessions × 2 and one skills re-training session plus Twice daily home practice sessions × 12 weeks |

SymptomsChronic Heart Failure Questionnaire QoLWorld Health Organization QoL – Brief questionnaire – physical subscale |

|

Between Groups – Relaxation vs. attention control

|

| Wang et al., 201351 | Adults hospitalized with Class II-III HF and report of insomnia | 128 |

|

20-minute nurse-led biofeedback session once or twice/day × up to 6 days |

Symptoms Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

|

Between Groups

|

| Meditation | |||||||

| Curiati et al., 200553 | Adults with Class I-II HF | 19 |

|

60-minute training sessions × 2 plus 30-minute twice daily home practice sessions × 12 weeks |

QoL MLWHFQ – physical subscale |

|

Between Groups

|

| Jayadevappa et al., 200750 | African American adults with Class II–III HF | 23 |

|

90-minute training sessions × 7 consecutive days plus Bi-weekly refresher meetings × 3 months plus Monthly meetings × another 3 months plus 15–20 minute twice daily home practice |

Symptoms Pain – SF-36 Bodily pain subscale QoL MLWHF – physical subscale |

|

Between Groups

|

| Sullivan et al., 200957 | Adults with Class I or greater HF | 217 |

|

2 ¼ hour training sessions, once/week × 8 weeks plus 30-minutes daily home practice |

QoL KCCQ – symptom score |

|

Between Groups

|

| Guided Imagery | |||||||

| Beniaminovitz et al., 200249 and Klaus et al., 200048 |

Adults with Class III HF | 29 (8) |

(Guided imagery) |

90-minute training sessions, once/week × 1 month plus 15-minute daily home practice sessions |

Symptoms Dyspnea – Guyatt Respiratory Scale, Transitional Dyspnea Scale QoL MLWHFQ – physical subscale |

|

Between Groups

|

HF = heart failure; KCCQ = Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; MLWHFQ = Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; QoL = Quality of life

Study Designs & Samples

Of the nine unique studies, six used a randomized controlled trial design46–53, two used a non-randomized controlled design54–57, and one used a quasi-experimental (one-group pretest-posttest) design.58 The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (n=6)46–50,52,57–58, with two completed in China51,54–56 and one in Brazil.53 Sample sizes were small (N < 50) in slightly over half of the studies (n=5).48–50,52–53,58 Participants were adults or older adults with CHF and/or COPD. Three studies required a minimum New York Heart Association CHF Class II or higher diagnosis47,50–51, and five reported average ejection fractions ≤ 40%47,49,50,57 or at least mild functional impairment.58 Only one study required symptoms experienced at a minimum level of severity as an eligibility criterion. Wang et al. required that participants had experienced insomnia in the last 3 nights to qualify for study participation.51

Symptom and Quality of Life Measures

Symptoms and quality of life were measured with a variety of different instruments (Table 3). Pain scores were reported in one study50, dyspnea scores were reported in 4 studies49,52,54,56,58, fatigue scores were reported in two studies54,56,58, and sleep disturbance scores were reported in one study.51 In addition to quantitative measures, participants’ qualitative, self-report comments about effects on pain, dyspnea, fatigue and sleep were reported in one study.46 Symptom-related QoL scores were reported in seven studies.47,49–50,52–53,55,57

Table 3.

Symptom and Quality of Life Measures Used

| Variable Measured | Scale |

|---|---|

| Pain | SF-36 bodily pain subscale50 |

| Dyspnea | Guyatt Respiratory Scale49 |

| Transitional Dyspnea Scale49 | |

| Borg Scale52 | |

| Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire dyspnea subscale58 | |

| Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire dyspnea subscale54,56 | |

| Fatigue | Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire fatigue subscale58 |

| Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire fatigue subscale54,56 | |

| Sleep Disturbance | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index51 |

| Symptom-related QoL | Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire47,49–50,52–53 |

| World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief questionnaire55 | |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire57 |

Citations indicate studies in which the scale was used.

Cognitive-Behavioral Strategy Training and Practice

Cognitive-behavioral strategies were delivered in one or more sessions, with a cumulative training time of 45 minutes52 to 2½ hours.57 Participants were typically asked to practice the cognitive-behavioral strategies one or two times per day46–47, 50, 52–57, for approximately 20–30 minutes.46–47, 50, 52–53, 57 The most common duration of training and practice (study period) was 6–12 weeks52–58, with one study as short as six inpatient hospital days and another as long as 15 weeks.51

Treatment Effects

Because of the small number of studies and variability in design, specific types of strategies, comparison groups, and measures, we present a qualitative synthesis of treatment effects, rather than meta-analysis.

Relaxation

Five studies used a relaxation strategy; four of these demonstrated at least some beneficial effect on symptoms or symptom-related QoL.46,47, 51, 54–56, 58 Twelve weeks of twice daily progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) practice resulted in less dyspnea, but no difference in fatigue or symptom-related QoL compared to attention control.54–56 Biofeedback delivered at bedtime resulted in better sleep quality compared to usual care51, however, a second study found no difference in symptoms or symptom-related QoL when active biofeedback was compared to placebo biofeedback.52 Mixed results were reported for multimodal relaxation strategies. Within group improvements in pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep were reported with relaxation using focused breathing, PMR, autogenic training, meditation and guided imagery46, but no difference in symptom-related QoL when compared to cardiac education.47 Reductions in fatigue, but not dyspnea, were reported in a trial using combined relaxation, distracting pleasant events, increased awareness of control, recognition of maladaptive thinking, and problem solving.58

Meditation

Meditation strategies were tested in three studies and found to have beneficial effects in two of those trials.53, 57 Daily meditation practice for 8–12 weeks resulted in better symptom-related QoL compared to attention control (talking about stress)53 and usual clinical care.57 No differences in pain or symptom-related QoL were found when comparing 6 months of daily mediation to heart failure education combined with daily reading or music listening.50

Guided imagery

One study tested daily guided imagery practice over a period of 6 weeks and found no benefit on symptoms or symptom-related QoL when compared to an exercise intervention.49 Within the guided imagery group, however, a significant improvement in symptom-related QoL, but not dyspnea, was reported from pre- to post treatment.48

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of primary studies testing the effect of cognitive-behavioral strategies on pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in patients with heart failure. There are a limited number of studies exploring cognitive-behavioral symptom management strategies in heart failure and their findings are mixed, however, seven of the nine studies demonstrated at least some beneficial effects of cognitive-behavioral strategies on symptoms or symptom-related QoL.47–48,51,53–58 Relaxation (PMR, biofeedback-assisted relaxation, autogenic training) meditation, guided imagery, or combinations of these strategies resulted in less dyspnea and better sleep compared to attention control or usual care conditions51,54–56, and reduced pain, dyspnea, fatigue and sleep disturbance within treatment groups (pre- to post-treatment).47,58 Symptom-related QoL was improved with meditation compared to attention control and usual care conditions53,57, and from pre- to post-treatment with guided imagery.48

Our findings extend those of Adler et al., who synthesized evidence-based palliative approaches to heart failure-related dyspnea, pain, and fatigue.59 In a review of systematic reviews published through 2008, Adler described potential benefit but insufficient evidence for relaxation strategies in managing dyspnea, and no systematic reviews addressing evidence for meditation or guided in heart failure symptom management.59 The current findings are consistent with reviews of cognitive-behavioral strategies for symptom management in other chronic health conditions including cancer60, fibromyalgia61, irritable bowel syndrome62, menopause63–64, multiple sclerosis65, and temporomandibular joint disorder.66 Previous reviews have commonly noted mixed results across studies, with numerous trials of small size and fair to poor quality, but demonstrating potential beneficial effects of cognitive-behavioral strategies in controlling illness- or treatment-related symptoms.59,60–65 Investigators have described individual differences in effects of cognitive-behavioral strategies, suggesting that certain personal and clinical characteristics may contribute to symptom relief, or lack thereof.67–68 Such individual differences may contribute to the mixed findings observed in the current and previous reviews of cognitive-behavioral symptom management studies. Future research should address the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral strategies for prevalent symptoms in advanced heart failure, as well as the characteristics of patients who obtain the greatest treatment benefit.

Although we included distraction in our search, none of the studies retrieved used distraction as a stand-alone strategy. One study used distracting pleasant events in combination with relaxation and several other cognitive coping strategies.58 Previous studies of symptoms including pain30, dyspnea34, have demonstrated reduction in symptom severity or unpleasantness through attention diversion alone. As attention may return to symptoms when the distracting stimulus is removed, such treatment may be useful for symptoms of short duration such as episodic activity-induced dyspnea or fatigue, breakthrough pain, or sleep disruption due to unwanted thoughts. Future research should explore the value of stand-alone distraction interventions for brief exacerbations of heart failure symptoms.

The majority of studies reviewed were of moderate quality.46–47,50–52,54–56,58 Three of the nine unique studies had quality scores below the midpoint of the quality rating scale (18), suggesting moderate risk of bias.48–49,53,57 Common areas of weakness across studies included absence of adherence to a treatment manual, failure to blind data collectors to group assignment, failure to facilitate similar treatment expectations across groups, failure to describe outcome measure reliability and sensitivity to change, lack of a priori power calculation to assure adequate sample size, and not conducting intent-to-treat analyses. The relatively few number of studies and low quality of reporting indicate that more rigorous studies are needed to definitively determine the value of cognitive-behavioral strategies in controlling pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in advanced heart failure.

Overall, the evidence-base for cognitive-behavioral symptom management strategies in patients with heart failure is fairly limited. The majority of studies were not conducted with symptom management as a primary aim, and none included patients with class IV heart failure. Only two studies specifically targeted somatic symptoms as a primary outcome in designing the study.49,51 The remaining seven studies were designed to evaluate effects of cognitive-behavioral strategies on physiologic heart failure outcomes (e.g., exercise capacity, sympathetic activation)47–48,52,57–58, comorbid psychologic disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety)46,57–58, and/or overall quality of life.50,52–57 Consequently, most of the studies reviewed did not have inclusion criteria related to symptom experience.46–49, 50, 52–57 In order to demonstrate symptom palliation, studies must include participants with advanced (class III and IV) heart failure who are experiencing some minimum level of symptoms to allow room for improvement.

Our review found variation in training protocols, with cognitive-behavioral strategies taught in 3 to 15 sessions of 45–90 minutes duration, often held weekly. One exception was a study conducted with hospitalized heart failure patients experiencing insomnia, where training was provided in a single 20-minute session.51 Daily practice was fairly uniformly prescribed for 20–30 minutes, once or twice per day.46–47,50–57 Practice was monitored through observation or a self-report diary in seven of nine studies.46–47,50–56 Training and practice duration was similar among studies that did and did not demonstrate improvements in symptoms.50, 52 More research is needed to identify the minimum required training duration and practice frequency to achieve symptom relief in patients with advanced heart failure who may have limited capacity to attend and engage in lengthy group or clinic-based treatment.

The studies reviewed included active (exercise, hear failure education)46–50,54–56, inactive (attention)52–56, or undefined (usual care)51,57 comparison conditions. Beneficial effects of cognitive-behavioral strategies were more common when compared to attention control or usual care conditions. Usual care conditions may be more reflective of the limitations of current practice, especially in persons with advanced heart failure who are unable to engage in vigorous comparison conditions (exercise) or refractory to strategies intended to impact heart failure management (education). Future research should first demonstrate the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral strategies for symptom palliation in advanced heart failure, and then progress to head-to-head comparative effectiveness trials among those strategies with demonstrated efficacy.

Several different instruments were used to measure symptoms and symptom-related quality of life (Table 3). Many of the scales used were not designed to provide an in depth, multidimensional assessment of a specific symptom, and are not commonly used in symptom palliation research. Two of the five studies that used the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHFQ)48,53 and the study that used the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)57 demonstrated a difference in symptom-related QoL with implementation of the cognitive-behavioral strategy.48,53,57 The study using the WHOQOL-Brief did not demonstrate improvement in symptom-related QoL.54–56 Both the MLWHFQ and KCCQ assess impact of heart failure symptoms on daily life.69,70 The MLWHFQ asks persons to rate the extent to which heart failure affected an individual’s life over the past month (‘none’ to ‘very much’), and the KCCQ asks persons to report the degree to which symptoms limited daily life (‘not at all limited’ to ‘extremely limited’). The KCCQ also asks about the frequency of symptom interference and bother over the past 2 weeks, for example, how many times has fatigue limited your ability to do what you want?’ and ‘how many times has fatigue bothered you?’ rated from ‘never’ to ‘all of the time’. Of the symptoms of interest in the current review, the MLWHFQ assesses three (dyspnea, fatigue, sleep) and the KCCQ assesses two (dyspnea, fatigue). Future research should expand measures to include more focused symptom inventories (measures of pain, dyspnea, fatigue, and sleep disturbance) and evaluate their reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change as compared to heart failure specific measures in this population.

The current review indicated that symptom relief varied across time. For example, Sullivan et al. reported that mindfulness meditation significantly improved symptom-related QoL compared to usual care at 6- and 12-months, but there were no between group differences at 3-months.57 Cully et al. demonstrated a reduction in fatigue 8 weeks after initiation of relaxation treatment, but this reduction did not persist at the 3-month assessment.58 These findings suggest that symptom relief is complex and multifactorial, possibly determined by time-related changes in medical condition and treatment, as well as the cognitive-behavioral strategy dose and duration of practice. More research is necessary to establish the temporal characteristics of cognitive-behavioral strategies for optimal symptom management in the advanced heart failure population.

Results of this review should be interpreted in light of limitations. While our search was systematic, it is possible that some relevant published studies were missed. The terminology used to describe cognitive-behavioral strategies differs with author preferences, and may not have been fully captured in our search terms. For example, relaxation, guided imagery, distraction, and meditation may be identified as “coping strategies”, “mind-body therapies” or “complementary health approaches”. Our review was limited to studies published in English, and it is possible that additional evidence is available in other languages. We did not contact authors to obtain additional information about study conduct or outcomes, and rather relied only on the data provided in the published reports. Finally, we did not attempt to deduce effect sizes or conduct a meta-analysis, given that many of the studies were not designed with symptom management as a primary aim.

Conclusion

The current systematic review is the first to document the potential beneficial effect of cognitive-behavioral symptom management strategies among patients with heart failure. In summary, findings suggest that the literature related to cognitive-behavioral strategies for heart failure symptom management varies in quality, but supports the importance of more rigorous research, testing strategies such as relaxation, meditation, and guided imagery for improved symptom control in heart failure patients. Because these symptoms share a common underlying component of distress, cognitive-behavioral strategies may be used to simultaneously target all four symptoms, as they often co-occur in persons with advanced heart failure. Cognitive-behavioral strategies could be particularly useful in the advanced heart failure patient population, where symptom palliation has been understudied. Drawing from the current review, future research should test cognitive-behavioral strategies in rigorously designed efficacy trials, using sample sizes based on a priori power calculations, with clear symptom-based inclusion criteria, using a treatment manual and sensitive symptom outcome measures, with data collected by research staff blinded to participants’ group assignment. Studies should also explore the minimum duration of training and practice to achieve symptom relief, the optimum timing in regard to the advanced heart failure trajectory, and individual difference variables that may contribute to treatment effects.

What’s New?

When heart failure progresses to advanced stages, symptom palliation efforts may be necessary, in addition to usual self-care for disease management.

In approximately half of controlled studies of patients with heart failure, relaxation, meditation, and guided imagery provided greater relief of dyspnea and sleep disturbance than usual care and attention control conditions. Some patients who received the strategies also reported improvements in pain and fatigue following treatment.

Cognitive-behavioral strategies have been effective for symptom management in other illness conditions, and show potential for benefit in controlling pain, dyspnea, fatigue and sleep disturbance in advanced heart failure. More research is needed to support their use in the palliative care of these patients.

Acknowledgment

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under awards number R01NR013468 (Kwekkeboom, PI) and R00NR012773 (Bratzke, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedrich EB, Böhm M. Management of end stage heart failure. Heart. 2007;93(5):626–631. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.098814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett SJ, Cordes DK, Westmoreland G, Castro R, Donnelly E. Self-care strategies for symptom management in patients with chronic heart failure. Nurs Res. 2000;49(3):139–145. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blinderman CD, Homel P, Bilings JA, Portenoy RK, Tennstedt SL. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(6):594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goebel JR, Doering LV, Shugarman LR, et al. Heart failure: The hidden problem of pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(5):698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodlin SJ, Wingate S, Albert NM, et al. Investigating pain in heart failure patients: The pain assessment, incidence, and nature in heart failure (PAIN-HF) study. J Card Fail. 2012;18(10):776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen DJA, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, Schols JM. Symptom distress in advanced chronic organ failure: Disagreement among patients and family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 5(4):447–456. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0394. 2–12; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tranmer JE, Heyland D, Dudgeon D, Groll D, Squires-Graham M, Coulson K. Measuring the symptom experience of seriously ill cancer and noncancer hospitalized patients near the end of life with the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(5):420–429. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C, et al. Predictors of quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure awaiting transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14(1):2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heo S, Doering L, Widener J, Moser DK. Predictors and effect of physical symptom status on health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(2):124–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Karkeken D, et al. Cognitive deficits and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(3):189–198. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181ca36fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ACCF/AHA guidelines for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation / American Health Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes D, Anstead MI, Ho J, Phillips BA. Insomnia and chronic heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2009;14(3):171–182. doi: 10.1007/s10741-008-9102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes S. The management of pain in end-stage heart failure. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2010;5(3):112–116. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Light-McGroary K, Goodlin SJ. The challenges of understanding and managing pain in the heart failure patient. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32835c1f2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wheeler M, Wingate S. Managing noncardiac pain in heart failure patients. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(6 Suppl):575–583. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200411001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurgens CY, Shurpin KM, Gumersell KA. Challenges and strategies for heart failure symptom management in older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(11):24–33. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20100930-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindenfeld J, Albert NM, Boehmer JP, et al. Executive summary: HFSA 2010 comprehensive heart failure practice guideline. J Card Fail. 2010;16(6):475–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oxberry SG, Johnson MJ. Review of the evidence for the management of dyspnoea in people with chronic heart failure. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2008;2(2):84–88. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282ff122e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zambroski CH, Bekelman DB. Palliative symptom management in patients with heart failure. Prog Palliat Care. 2008;16(5–6):241–249. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pozehl B, Duncan K, Hertzog M. The effects of exercise training on fatigue and dyspnea in heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;7(2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heart Failure Society of America. Section 6. Nonpharmacologic management and health care maintenance in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2010;16(6):e61–e72. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan CX, Morrison RS, Ness J, Fugh-Berman A, Leipzig RM. Complementary and alternative medicine in the management of pain, dyspnea, and nausea and vomiting near the end of life: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(5):374–387. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman SM. Cognitive behavioral therapy within the palliative care setting. In: Sorocco KH, Lauderdale S, editors. Cognitive behavior therapy with older adults: Innovations across care settings. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2011. pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turk DC, Feldman CS. A cognitive-behavioral approach to symptom management in palliative care: Augmenting somatic interventions. In: H. M Cheochinov HM, Breitbart W, editors. Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suls J, Howren MB. Understanding the physical-symptom experience: The distinctive contributions of anxiety and depression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21(2):129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerns RD, Sellinger J, Goodin BR. Psychological treatment of chronic pain. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:411–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-090310-120430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casida J, Lemanski SA. An evidence-based review on guided imagery utilization in adult cardiac surgery. Clinical Scholars Review. 2010;3(1):22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwekkeboom KL, Gretarsdottir E. Systematic review of relaxation interventions for pain. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38(3):269–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malloy KM, Milling LS. The effectiveness of virtual reality distraction for pain reduction: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(8):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Persson AL, Veenhuizen H, Zachrison L, Gard G. Relaxation as treatment for chronic musculoskeletal pain – a systematic review of randomized controlled studies. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2008;13(5):355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Posadski P, Ernst E. Guided imagery for musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(7):648–653. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31821124a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai WS, Chao CS, Yang WP, Chen CH. Efficacy of guided imagery with theta music for advanced cancer patients with dyspnea: A pilot study. Biol Res Nurs. 2010;12(2):188–197. doi: 10.1177/1099800409347556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Leupoldt A, Seemann N, Gugleva T, Dahme B. Attentional distraction reduces the affective but not the sensory dimension of perceived dyspnea. Respir Med. 2007;101(4):839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SD, Kim HS. Effects of a relaxation breathing exercise on fatigue in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(1):51–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menzies V, Lyon D, Elswick R, McCain N, Gray D. Effects of guided imagery on biobehavioral factors in women with fibromyalgia. J Behav Med. 2014;37(1):70–80. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9464-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvey AG, Payne S. The management of unwanted pre-sleep thoughts in insomnia: Distraction with imagery versus general distraction. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(3):267–277. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: update of the recent evidence (1998–2004) Sleep. 2006;29(11):1398–1414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson S. Effects of relaxation and imagery on the sleep of critically ill adults. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2003;22(4):182–190. doi: 10.1097/00003465-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwekkeboom KL, Abbott-Anderson K, Cherwin C, Roiland R, Serlin RC, Ward SE. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a patient-controlled cognitive-behavioral intervention for the pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance symptom cluster in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(6):810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.12.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yates SL, Morley S, Eccleston C, de C Williams AC. A scale for rating the quality of psychological trials for pain. Pain. 2005;117(3):314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dekker RL. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in patients with heart failure: A critical review. Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;43(1):155–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Hea E, Houseman J, Bedck K, Sposato R. The use of cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depression for individuals with CHF. Heart Fail Rev. 2009;14(1):13–20. doi: 10.1007/s10741-008-9081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woltz PC, Chapa DW, Friedmann E, Son H, Akintade B, Thomas S. Care of the patient with heart failure: Effects of interventions on depression in heart failure: A systematic review. Heart Lung. 2012;41(5):469–283. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang BH, Jones D, Hendricks A, Boehmer U, LoCastro JS, Slawsky M. Relaxation response for Veterans Affairs patients with congestive heart failure: Results from a qualitative study within a clinical trial. Prev Cardiol. 2004;7(2):64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang BH, Hendricks A, Zhao Y, Rothendler JA, LoCastro JS, Slawsky M. A relaxation response randomized trial on patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2005;25(3):149–157. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klaus L, Beniaminovitz A, Choi L, et al. Pilot study of guided imagery use in patients with severe heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86(1):101–104. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00838-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beniaminovitz A, Lang CC, LaManca J, Mancini DM. Selective low-level leg muscle training alleviates dyspnea in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(9):1602–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jayadevappa R, Johnson JC, Bloom BS, et al. Effectiveness of Transcendental Meditation on functional capacity and quality of life of African Americans with congestive heart failure: A randomized control study. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(1):72–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang LN, Tao H, Zhao Y, Zhou YQ, Jiang XR. Optimal timing for initiation of biofeedback-assisted relaxation training in hospitalized coronary heart disease patients with sleep disturbances. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(4):367–376. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318297c41b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swanson KS, Gevirtz RN, Brown M, Spira J, Guarneri E, Stoletniy L. The effect of biofeedback on function in patients with heart failure. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2009;34(2):71–91. doi: 10.1007/s10484-009-9077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curiati JA, Bocchi E, Freire JO, et al. Meditation reduces sympathetic activation and improves the quality of life in elderly patients with optimally treated heart failure: A prospective randomized study. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(3):465–472. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J. Effects of relaxation therapy on psychologic distress and symptom status in older Chinese patients with heart failure. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(4):427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J. Improving health-related quality of life of patients with chronic heart failure: Effects of relaxation therapy. J Adv. Nurs. 2010;66(2):392–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J, Hui E. Non-pharmacological interventions in older people with heart failure: Effects of exercise training and relaxation therapy. Gerontology. 2007;53(2):74–81. doi: 10.1159/000096427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan MJ, Wood L, Terry J, et al. The support, education, and research in chronic heart failure study (SEARCH): A mindfulness-based psychoeducational intervention improves depression and clinical symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;157(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cully JA, Stanley MA, Deswal A, Hanania NA, Phillips LL, Kunik ME. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic cardiopulmonary conditions: Preliminary outcomes from an open trial. Prim Care Companion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4) doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00896blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adler ED, Goldfinger JZ, Kalman J, Park ME, Meier DE. Palliative care in the treatment of advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:2597–2606. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.869123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kwekkeboom KL, Cherwin CH, Lee JW, Wanta B. Mind-body treatments for the pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom cluster in persons with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(1):126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kozasa EH, Tanaka LH, Monson C, Little S, Leao FC, Peres MP. The effects of meditation-based interventions on the treatment of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(5):383–387. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Effect of antidepressant and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1350–1365. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Vishnu A. Mind-body therapies for menopausal symptoms: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2010;66(2):135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tremblay A, Sheeran L, Aranda SK. Psychoeducational interventions to alleviate hot flashes: A systematic review. Menopause. 2008;15(1):193–202. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31805c08dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Senders A, Wahbeh H, Spain R, Shinto L. Mind-body medicine for multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Autoimmune Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/567324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Medlicott MS, Harris SR. A systematic review of the effectiveness of exercise, manual therapy, electrotherapy, relaxation training, and biofeedback in the management of temporomandibular disorder. Phs Ther. 2006;86(7):955–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwekkeboom KL, Wanta B, Bumpus M. Individual difference variables and the effects of progressive muscle relaxation and analgesic imagery interventions on cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(6):604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Owens JE, Taylor AG, DeGood D. Complementary and alternative medicine and psychological factors: Toward an individual differences model of complementary and alternative medicine use and outcomes. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5(6):529–541. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(5):1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rector TS, Kubo SH, Cohn JN. Patients’ self-assessment of their congestive heart failure: Content, reliability and validity of a new measure, the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. Heart Failure. 1987;3:198–209. [Google Scholar]