Abstract

Late-life depression (major depression occurring in an adult 60 years or older) is a common condition that frequently presents with cognitive impairment. Up to half of individuals with LLD are estimated to have cognitive impairment greater than that of age- and education-matched comparators, with impairments of episodic memory, speed of information processing, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability being most common. To inform our understanding of the state- versus trait-effects of depression on neuropsychological functioning, and to overcome limitations of previous studies, we utilized baseline data from the longitudinal Pathways study to compare differences in single time point performance on a broad-based neuropsychological battery across three diagnostic groups of older adults, each comprised of unique participants (N=438): currently depressed (n=120), previously depressed but currently euthymic (n=190), and never-depressed (n=128). Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that participants with a history of depression (currently or previously depressed) performed significantly worse than never-depressed participants on most tests of global cognition, as well as on tests of episodic memory, attention and processing speed, verbal ability, and visuospatial ability; in general, differences were most pronounced within the domain of attention and processing speed. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not observe differences in executive performance between the two depression groups, suggesting that certain aspects of executive functioning are “trait deficits” associated with LLD. These findings are in general agreement with the existing literature, and represent an enhancement in methodological rigor over previous studies given the cross-sectional approach that avoids practice effects on test performance.

Keywords: cognitive function, neuropsychological, depression, elderly, geriatric, assessment

Introduction

Late-life depression (LLD), defined as major depression occurring in an older adult (60 years or older), is a significant public health concern. Epidemiological data indicate LLD prevalence rates of 1-4% among community-dwelling older adults, with higher prevalence (10-20%) among individuals hospitalized for medical or surgical reasons [1]. LLD has negative effects on quality of life, global functioning, physical health, as well as cognition, and up to half of individuals with LLD are estimated to have cognitive impairment greater than that of age- and education-equated comparison subjects [2, 3]. Such cognitive deficits have been associated with higher depression relapse rates, poorer response to antidepressant treatment, and greater overall disability, and include impairments of episodic memory, speed of information processing, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability [2-8]. Of these domains, information processing speed and executive functioning are considered to be particularly vulnerable, and several studies have reported that cognitive impairment associated with LLD is predominantly mediated by slowed speed of information processing and/or working memory deficits [2, 4]. In addition, increasing evidence suggests that depression in older adults contributes to the development of persistent cognitive dysfunction in a subset of individuals [9], and is associated with an approximately 50% increased likelihood of developing all-cause dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia [10].

To date, most studies of neuropsychological functioning in LLD have focused primarily on individuals in acute depressive episodes (i.e., currently depressed). Older depressed patients perform significantly worse on measures of both processing speed and working memory, and while performance on these measures improves in patients whose depression remits, the extent of improvement is no greater than improvement seen in comparison subjects who undergo repeated testing [4]. In a similar vein, relative to non-depressed comparison subjects, older depressed patients perform worse on a range of cognitive tasks, with information processing speed and visuospatial and executive abilities being the most broadly impaired [2]. Age, depression severity, education, race, and presence of vascular risk factors have all been found to make significant and independent contributions to cognitive impairment in LLD, with changes in information processing speed most fully mediating the influence of predictor variables on impairments in other cognitive domains [3, 11].

The comparison of neuropsychological functioning in individuals during and after resolution of a major depressive episode suggests that a subset of LLD patients may exhibit an improvement in cognition following antidepressant treatment [12], but a significant proportion will continue to experience cognitive impairment following resolution of their depressive symptoms [11, 13-17]. In one study, 45% of individuals with LLD were cognitively impaired after one year of follow-up, and 94% of individuals with cognitive impairment at study baseline remained impaired one year later, despite reaching depression remission [13]. Others have similarly noted persistent cognitive impairment following treatment and/or remission of depressive symptoms [11, 12, 16, 18, 19], with certain risk factors, including lower baseline cognitive function, older age, later age of depression onset, and greater vascular burden associated with less improvement in specific cognitive domains [20]. Limitations of such studies, however, have included the confounding effects of practice (i.e., performance improvement resulting from repeated testing) and time (e.g., in a progressive disease such as Alzheimer’s disease, the neuropathology may have progressed from the time that the patient was first tested, during the depressive episode, and the time that the patient was re-tested, after the episode resolved). In addition, the generalizability of such studies has been limited by small group size, as well as the use of cognitive screening measures (as opposed to more comprehensive neuropsychological assessments).

To further inform our understanding of the state-effects of depression on neuropsychological functioning, and to overcome limitations of previous studies, we utilized baseline data from a large group of participants in the longitudinal Pathways Linking Depression to MCI and Dementia (“Pathways”) study to compare differences at single time point performance on a broad-based neuropsychological battery in three patient groups: currently depressed older adults (n=120), previously depressed but currently euthymic (i.e., depression had remitted) older adults (n=190), and never-depressed older adults (n=128). We hypothesized that (A) currently and previously depressed Pathways participants would perform significantly worse than never-depressed participants on baseline neuropsychological tests measuring global cognition, episodic memory, attention/processing speed, verbal ability, and visuospatial ability. Furthermore, we predicted that (B) attention/processing speed would show the greatest degree of impairment, relative to scores for never-depressed control participants. Finally, based on previous work by our group demonstrating that executive functioning among older adults with depression improves after antidepressant treatment [13], we predicted that (C) participants in the depressed-euthymic group would perform better than participants in the currently depressed group on measures of executive functioning, but that (D) both depressed groups would perform worse on tests of executive functioning than never-depressed control participants [11].

Materials and Methods

Participants and exclusion criteria

Participants were recruited via advertisements from the University of Pittsburgh’s NIMH-funded Advanced Center for Intervention Research for Late-Life Mood Disorders (ACISR/LLMD) between 1996 and 2012. The ACSIR/LLMD provides a research infrastructure to promote investigations for the care of elderly individuals living with depression, across the spectrum of cognitive functioning. Depressed Pathways participants completed at least one intervention trial through the ACSIR/LLMD. Participants were excluded if they had psychotic symptoms or major unstable medical illness, although individuals with chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension) were not excluded if medically stable. Additional exclusion criteria included: neurologic disorders or injuries known to have significant direct effects on cognitive functioning (e.g., traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis), uncorrected sensory handicap that would preclude participation in cognitive testing (e.g., blindness), and either having a pre-existing clinical diagnosis of dementia (e.g., by a primary care physician) or receiving a diagnosis of dementia from the University of Pittsburgh’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) either before or following resolution of the participant’s index depressive episode. Written informed consent, approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), was obtained for all participants. After consenting to the study, participants completed a battery of neurobiological and clinical measures, including a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment.

Measures and instruments

Diagnosis and Symptom Severity

Baseline psychiatric diagnoses were established by the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-IV) [21]—administered by trained master’s- and doctoral-level clinicians—followed by a consensus diagnostic conference attended by raters and at least three research geriatric psychiatrists. At time of entry into Pathways, each participant also received an extensive medical evaluation that included medical and neurological history (including score on the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics, CIRS-G [22], and assessment of cardiovascular risk factors, CIRS-G combined heart and vascular scale scores) and a physical examination. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17) [23] was administered to all participants at time of neuropsychological testing in order to measure depressive symptom severity.

Neuropsychological evaluation

Described elsewhere in greater detail [2, 19], the neuropsychological evaluation was designed to assess multiple cognitive domains, and included the administration of 22 well-validated scales or tasks by trained examiners, closely supervised by a senior neuropsychologist (M.A.B.). Measures of global cognition included: Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) and Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE). Measure of premorbid intellectual ability: Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). Measures of delayed episodic memory included: Logical Memory (LM) subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale 3, free recall (CVLT) and recognition (CVLT-R) of the California Verbal Learning Test, and delayed copy of the Modified Rey-Osterrieth Figure (MREY-D). Measures of executive functioning included: Trail Making Test Part B (TRL-B), Executive Interview (EXIT), Stroop Color-Word Inhibition Test (Stroop), and Wisconsin Card-Sorting Test (WCST). Measures of attention/processing speed included: Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), Grooved Pegboard Test (GP), Trail Making Test Part A (TRL-A), and Finger Tapping Test (FT). Measures of verbal ability included Semantic Fluency Test (SF), Modified Boston Naming Test (MBNT), Spot the Word Test (STW), and Letter Fluency Test (LF). Finally, measures of visuospatial ability included: Block Design Subtest (BD) of the WAIS-III, Clock Drawing Test (CDT), immediate copy of the Modified Rey-Osterrieth Figure (MREY-C), and Simple Drawings Test (SD).

Depression Diagnostic (Group) Assignment

For the current study, we examined data for all participants (N=438) who completed an initial (i.e., baseline) Pathways comprehensive neuropsychological assessment. Participants were divided into three groups, based on MDD diagnostic status and degree of depressive symptomatology. The first group (n=128) included participants with no previous or current history of MDD (Never Depressed, ND). The second group (n=190) included participants who met DSM-IV criteria for MDD in the past (recent or remote) but were euthymic at time of baseline cognitive assessment, as defined by HRSD-17<12 (MDD-Euthymic, MDD-E). The third group (n=120) included participants who met DSM-IV criteria for MDD and were depressed at the time of baseline cognitive assessment, as defined by HRSD-17≥12 (MDD-Depressed, MDD-D).

Statistics

Descriptive analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation or percentage and N) were used to characterize and compare the three diagnostic groups (ND, MDD-E, MDD-D). Distributions were examined prior to all analyses. Continuous measures were compared using ANOVA, and categorical variables were compared using chi-square test. When an overall group difference was observed, pairwise comparison with Bonferroni adjustment was used to determine which groups differed. Effect size was calculated using eta-squared (for continuous measures) and phi coefficient (for categorical measures). Age of MDD onset was compared between the MDD-E and MDD-D groups using a t-test, and effect size was calculated using Cohen’s D.

Normalization and comparison of neuropsychological scores

Raw scores for the 22 neuropsychological tests were converted to Z-scores based on distribution scores for the never-depressed (ND) subjects. To simplify score interpretation, normalized scores were then standardized using a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15 (i.e., the overall mean and standard deviation for the ND group was 100 and 15, respectively). These scores were compared between the ND, MDD-E, and MDD-D groups using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model adjusting for age, education, gender, race, and medical burden. Hochberg’s adjusted overall p-value was used to correct for multiple comparisons between tests and to determine the overall difference across groups [24]. When an overall group difference was observed, pairwise comparisons between the MDD-D, MDD-E, and ND groups were made using a Bonferroni adjustment.

Results

As summarized in Table 1a, the three diagnostic groups (Never Depressed, MDD-Euthymic, MDD-Depressed) differed significantly in age (p=.0002), gender distribution (p=.007), and years of education (p=.01), but not racial distribution. The MDD-E group was the oldest, differing from the overall group mean by 1.5 years. The ND group had the lowest percentage of female participants (60.9%), though all groups had more females than males. While the ND group was the most-educated of the three, the absolute difference across all groups (about 1 year of education) was negligible. Of note, MDD-E participants had significantly greater medical comorbidity than MDD-D and ND participants, as measured by both CIRS-G total (p<.0001) and number of cardiovascular risk factors (p=.0002). As expected by group assignment, HRSD-17 totals were highest among MDD-D participants (mean [SD] = 18.28[4.5]), with significantly lower totals for the MDD-E (5.83[2.7]) and ND (2.46[1.9]) groups (p<.0001). Age of first major depressive episode and pattern of depressive illness (single vs. recurrent) were compared for the MDD-D and MDD-E groups, and neither differed significantly. Roughly half of all MDD-D and MDD-E participants reported a history of recurrent depression, and the average age of depression onset for both groups was approximately 56 years.

Table 1a. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Diagnostic and Depression Status.

| All Participants (N=438) |

Never Depressed (n=128) |

MDD-Euthymic (n=190) |

MDD-Depressed (n=120) |

Test of Significance | Effect Size (η2, φ, or d) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and Clinical Measures (Mean (SD) or % (n) [n if reduced sample]) | ||||||

| Age (Years) | 72.51 (6.9) | 71.43 (7.1) | 74.04 (6.5) | 71.23 (7.0) | F(2,435)=8.5, p=0.0002 (Post-Hoc: MDD-E>MDD-D,ND) |

0.04 |

|

Gender(%

Female) |

71.5% (n=313) | 60.9% (n=78) | 76.3% (n=145) | 75.0% (n=90) | x2(2)=9.9, p=0.007 (Post-Hoc: MDD-E, MDD-D>ND) |

0.15 |

|

Race(%

White) |

88.4% (n=387) | 87.5% (n=112) | 91.1% (n=173) | 85.0% (n=102) | x2(2)=2.7, p=0.25 | 0.08 |

|

Education

(Years) |

13.76 (2.6) | 14.18 (2.7) | 13.81 (2.6) | 13.23 (2.5) | F(2,435)=4.3, p=0.01 (Post-Hoc: ND>MDD-D) |

0.02 |

|

CIRS-G

(Total) |

9.0 (3.9) [n=424] | 6.99 (3.6) [n=120] | 10.80 (3.7) [n=184] | 8.23 (3.4) | F(2,421)=44.9, p<0.0001 (Post-Hoc: MDD-E>MDD-D>ND) |

0.18 |

|

CVRFs

(Total) |

2.00 (1.3) [n=390] | 1.70 (1.4) [n=122] | 2.29 (1.3) [n=178] | 1.82 (1.0) [n=90] | F(2,387)=8.8, p=0.0002 (Post-Hoc: MDD-E>MDD-DD,ND) |

0.04 |

|

HRSD-17

(Total) |

8.26 (7.0) | 2.46 (1.9) | 5.83 (2.7) | 18.28 (4.5) | F(2,435)=894.0, p<0.0001 (Post-Hoc: MDD-D>MDD-E>ND) |

0.80 |

| Age at First Major Depressive Episode Onset (Years) | 56.35 (20.2) | 55.89 (19.2) | t(308)=0.20, p=0.84 | 0.02 | ||

| Major Depressive Episode Pattern (% Single-Episode) | 50.5% (n=96) | 48.3% (n=58) | x2(1)=0.14, p=0.71 | −0.02 | ||

Next, standardized scores of 22 neuropsychological tests were compared between the ND, MDD-E, and MDD-D groups using an ANCOVA model adjusting for age, education, gender, race, and medical burden (CIRS-G total). (Non-standardized test performance may be found in Supplementary Table 1) Each risk factor was found to influence the results of one or more cognitive tests, with age and education being the most frequent confounders (Table 1b).

Table 1b. Standardized Neuropsychological Test Scores (Mean (SD) or % (n) [n if reduced sample]).

| Never Depressed(n=128) | MDD-Euthymic (n=190) | MDD-Depressed (n=120) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Measures of Global Cognition and Premorbid Intellectual Ability | |||

| Dementia Rating Scale (DRS)1 | 100 (15) | 91.61 (22.9) | 90.08 (25.6) |

| Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)1 | 100 (15) | 85.54 (30.2) | 86.30 (31.7) |

| Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR)2 | 100 (15) [n=109] | 99.39 (17.5) [n=152] | 95.66 (13.3) [n=37] |

| B. Delayed Memory: | |||

| Wechsler Logical Memory (LM) Subtest | 100 (15) [n=125] | 91.47 (20.6) [n=146] | 88.84 (20.1) [n=110] |

| California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) Free Recall | 100 (15) | 91.73 (18.2) [n=188] | 91.91 (17.2) [n=112] |

| California Verbal Learning Test Recognition (CVLT-R) | 100 (15) [n=124] | 89.45 (27.0) [n=188] | 88.71 (27.7) [n=112] |

| Modified Rey-Osterrieth, delay copy (MREY-D) | 100 (15) [n=127] | 93.25 (17.8) [n=164] | 92.42 (17.6) [n=110] |

| C. Executive Functions: | |||

| Trail Making Test Part B (TRL-B) | 100 (15) [n=127] | 84.83 (33.7) [n=156] | 86.63 (39.5) [n=108] |

| Executive Interview (EXIT) | 100 (15) [n=127] | 91.61 (21.2) [n=187] | 90.85 (19.1) [n=110] |

| Stroop Color-Word Inhibition Test (Stroop) | 100 (15) [n=124] | 92.19 (28.0) [n=156] | 93.77 (22.0) [n=114] |

| Wisc. Card-Sorting Test (WCST) Total Errors | 100 (15) [n=124] | 96.77 (16.1) [n=140] | 93.89 (17.5) [n=106] |

| D. Attention/Processing Speed: | |||

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) | 100 (15) [n=127] | 87.35 (18.0) [n=181] | 88.55 (17.9) [n=114] |

| Grooved Pegboard Test (GP) | 100 (15) [n=125] | 86.22 (29.4) [n=157] | 84.52 (28.1) [n=113] |

| Trail Making Test Part A (TRL-A) | 100 (15) [n=127] | 87.19 (31.5) [n=164] | 85.33 (36.1) [n=114] |

| Finger Tapping Test (FT) | 100 (15) [n=117] | 95.37 (14.2) [n=125] | 97.62 (14.2) [n=107] |

| E. Verbal Ability: | |||

| Semantic Fluency Test (SF) | 100 (15) | 92.88 (17.1) [n=188] | 91.09 (15.0) [n=118] |

| Modified Boston Naming Test (MBNT) | 100 (15) [n=127] | 94.02 (19.2) [n=188] | 89.25 (20.6) [n=118] |

| Spot the Word Test (STW) | 100 (15) [n=125] | 96.56 (17.9) [n=140] | 93.40 (16.5) [n=103] |

| Letter Fluency Test (LF) | 100 (15) | 96.58 (13.8) [n=188] | 94.97 (14.7) [n=117] |

| F. Visuospatial Ability: | |||

| Block Design Test (BD) | 100 (15) [n=126] | 90.84 (13.9) [n=145] | 90.19 (14.1) [n=109] |

| Clock Drawing Test (CDT) | 100 (15) | 96.69 (19.3) [n=188] | 92.66 (15.8) [n=116] |

| Modified Rey-Osterrieth, copy (MREY-C) | 100 (15) [n=127] | 95.78 (19.8) [n=165] | 96.44 (18.9) [n=111] |

| Simple Drawings Test (SD) | 100 (15) | 97.07 (14.8) [n=188] | 99.68 (14.6) [n=116] |

Measure of Global Cognition.

Measure of Premorbid Intellectual Ability.

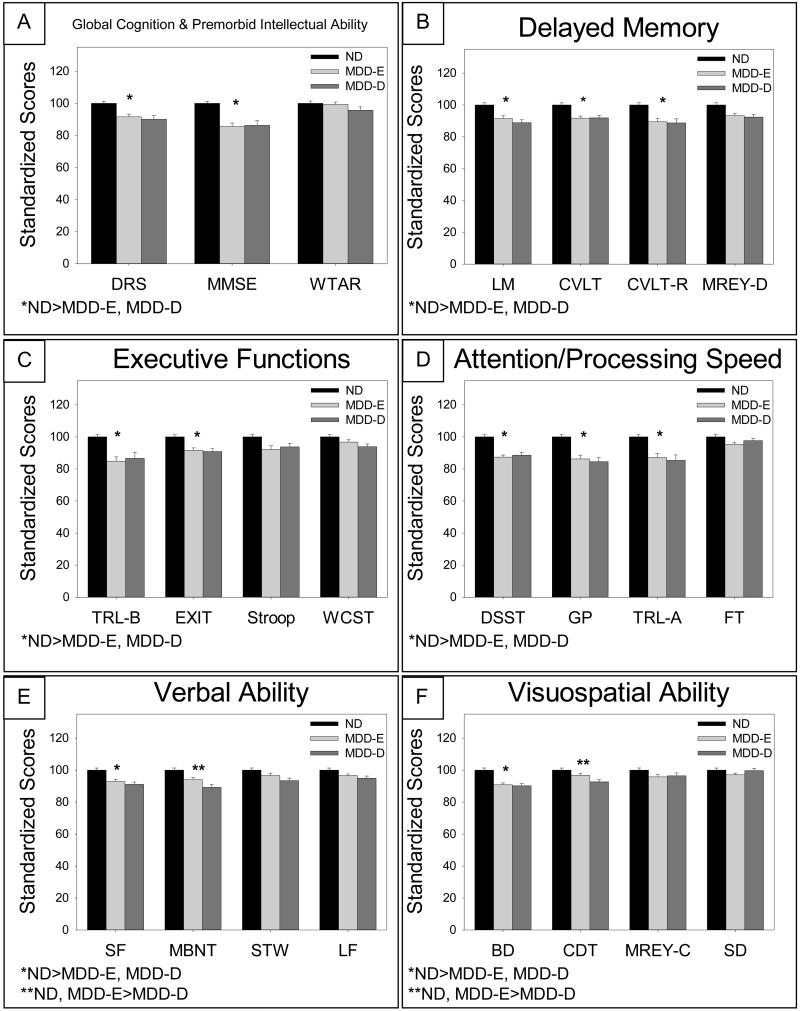

As enumerated in Table 1a and depicted in Figure 1, we found an overall difference in standardized scores for the ND, MDD-E, and MDD-D groups on 2 (DRS, MMSE) of 3 measures of global cognition and premorbid intellectual ability (A), 3 (LM, CVLT, CVLT-R) of 4 measures of delayed memory (B), 3 (DSST, GP, TRL-A) of 4 measures of attention and processing speed (D), 2 (SF, MBNT) of 4 measures of verbal ability (E), and 2 (BD, CDT) of 4 measures of visuospatial ability (F). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that never-depressed participants performed better than MDD-E and MDD-D participants on all measures that differed significantly. In addition, within the language domain (i.e., verbal ability), the ND group performed significantly better than both depressed groups on Semantic Fluency (SF), but the MDD-E group performed similarly to the ND group on the Boston Naming Test (MBNT). Within visuospatial ability, the ND group performed significantly better than both depressed groups on Block Design (BD), but the MDD-E group performed similarly to the ND group on Clock Drawing (CDT). Within each domain, there was at least one test that did not differ significantly across the diagnostic groups, including WTAR (global cognition and premorbid intellectual ability), MREY-D (delayed memory), FT (attention and processing speed), STW and LF (verbal ability), and MREY-C and SD (visuospatial ability).

Figure 1. Standardized Test Scores Across Diagnostic Groups (Adjusting for Demographic Covariates).

Measures of global cognition and premorbid intellectual ability: Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS), Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), and Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). Measures of delayed memory: Logical Memory (LM) subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale, free recall (CVLT) and recognition (CVLT-R) of the California Verbal Learning Test, California Verbal Learning Test recognition memory (CVLT-R) and delayed copy of the Modified Rey-Osterrieth Figure (MREY-D). Measures of executive functioning: Trail Making Test Part B (TRL-B), Executive Interview (EXIT), Stroop Color-Word Inhibition Test (Stroop), and Wisconsin Card-Sorting Test (WCST). Measures of attention/processing speed: Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), Grooved Pegboard Test (GP), Trail Making Test Part A (TRL-A), and Finger Tapping Test (FT). Measures of verbal ability: Semantic Fluency Test (SF), Modified Boston Naming Test (MBNT), Spot the Word Test (STW), and Letter Fluency Test (LF). Measures of visuospatial ability: Block Design Test (BD), Clock Drawing Test (CDT), immediate copy of the Modified Rey-Osterrieth Figure (MREY-C), and Simple Drawings Test (SD).

As predicted, tasks within the attention and processing speed domain recorded many of the lowest standardized scores for the MDD-E and MDD-D groups (Digit Symbol: MDD-E mean=87.4, MDD-D mean=88.6; Grooved Pegboard: MDD-E mean=86.2, MDD-D mean=84.5; Trail Making A: MDD-E mean=87.2, MDD-D mean=85.3). Of all tests administered, MDD-D participants performed poorest on the Grooved Pegboard, followed by Trail Making-A. MDD-E participants, on the other hand, performed poorest on Trail Making-B (a set-shifting test of executive functioning), followed closely by the Grooved Pegboard. Interestingly, the Grooved Pegboard task, which requires both cognitive and motor speed, proved particularly difficult for both groups with a history of depression. Contrary to our prediction, Finger Tapping—a purer measure of fine motor speed (without a cognitive component)—did not differ significantly across the three groups.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that scores on all four executive tasks did not differ significantly between the two depression groups (MDD-E and MDD-D). Scores for both depression groups (MDD-E, MDD-D) were significantly lower than scores for the ND group on the TRL-B and EXIT, while scores on the Stroop and WCST did not differ significantly across any of the groups.

Discussion

We found that participants with a history of depression (MDD-D or MDD-E) performed significantly worse than never-depressed participants on most tests of global cognition, as well as on tests of delayed memory, attention and processing speed, verbal ability, and visuospatial ability. Our findings confirmed that, in general, differences in cognition between the never-depressed and depressed groups were most pronounced within attention and processing speed, with the additional finding that both depression groups performed particularly poorly on the Grooved Pegboard task, which required elements of both cognitive and motor processing. However, some inconsistency within domains was observed. For example, scores on Finger Tapping—a “purer” measure of fine motor speed—did not differ across groups, suggesting that differences on tasks with a “speed component” may be due to cognitive rather than motor slowing. To ensure that this finding was not due to a medication effect, we examined rates of sedative/hypnotic, anticholinergic, and antidepressant use, as each of these classes has the potential to impact motor speed. The MDD-E group had the greatest overall exposure to these medications, followed by the MDD-D group and, finally, the ND group. Despite this, the MDD-D and MDD-E groups exhibited similar levels of impairment on the Grooved Pegboard task, suggesting that impairment on this task is a “trait” effect of depression that is independent of medication status. We did not observe any differences in executive performance between the two depression groups (MDD-E and MDD-D), and scores for both groups were markedly lower than scores for the ND group on the Trails-B and EXIT. However, scores on the Stroop and WCST—two other measures of executive functioning—did not differ between any groups. The finding of persistent or “trait-like” cognitive impairment in the MDD-E group may represent the risk for dementia conferred by LLD or perhaps the prodromal expression of dementia. However, it does not exclude the possibility that these individuals also had executive impairments before the onset of depression.

We also found that several risk factors influenced performance on cognitive testing. Patients who were older or less educated performed worse on nearly all tests administered. Females performed significantly better than males on a number of tests (Logical Memory, California Verbal Learning Test, Digit Symbol, Spot the Word, Clock Draw), and significantly worse on others (MREY-Delayed Recall, Finger Tapping, Boston Naming Test). Medical burden was not associated with performance on the majority of tests administered, similar to findings reported by others and consistent with current thought that cognitive dysfunction associated with LLD is largely independent of high medical burden that characterizes the depressed older adult population [2, 25]. Interestingly, CIRS-G medical burden (which includes vascular risk factors) was not associated with performance on any tests of memory or executive functioning, in contrast to findings by others [20].

These results provide further support for the conclusion that LLD patients as a whole are characterized by impairments of episodic memory, speed of information processing, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability [2-8, 26], and that of these domains, information processing speed and executive functioning are particularly vulnerable. By circumventing the confounding effects of practice (i.e., performance change resulting from repeated testing) and time (often seen in progressive neurodegenerative diseases) in the current analyses, the robustness of this pattern of findings is enhanced. As in previous reports by our group, the generalizability of the findings was maximized by large sample size, the inclusion of older adult comparator subjects (to control for normal age-related cognitive changes), and use of a comprehensive neuropsychological battery that assesses a wide range of cognitive functions [2]. Apart from these strengths, one limitation was the demographic differences (e.g., age, gender, education, and medical comorbidity) observed across the three diagnostic groups. Though our analyses were designed to control for these differences, such adjustments are merely estimates, and greater similarities across the groups would have been preferable.

Our results reinforce a growing appreciation—over the last decade or so—that depressive “pseudo-dementia,” in which older adults recover cognitive function as their mood improves, occurs only rarely. In general, there is nothing “pseudo” in the cognitive impairments associated with late-life depression. Discerning differences in the “trait” vs. “state” effects of depression on neuropsychological functioning remains a challenging endeavor, however, and the results of studies to date are decidedly mixed. State effects are expected to be present only during the clinical depressive episode, while trait effects are expected to endure after depressive symptoms have resolved. In a recent study, Koehler and colleagues [27] examined older subjects with and without MDD, and found that tests of global cognition, memory, executive functioning, and processing speed did not differ significantly when mood, remission status, or antidepressant treatment were taken into account. The authors concluded that cognitive deficits in late-life depression persist over months to years, affect multiple domains, and are a manifestation of trait rather than state effects of depression. Barch and colleagues [20], on the other hand, examined individuals with late life depression both prior to and following treatment with sertraline, and found that episodic memory and executive function improved significantly following treatment, concluding that impairments in these domains may be associated with state effects of depression. However, they did not have a control group, so they were unable to definitely determine that the cognitive change reflected a response to treatment rather than practice effects. On the whole, there likely is a subset of individuals with LLD and cognitive impairment who will demonstrate an improvement in cognition following treatment (supporting the role of “state” effects), though a significant proportion will continue to experience impairment in several cognitive domains, even in individuals who achieve depression remission (supporting the role of “trait” effects) [9]. Finally, it is also interesting to note that MCI seems to be a risk factor for depression, underscoring the bidirectional relationship between depression and cognitive impairment. This relationship may be characterized by (or in fact represent) a downward spiral, with each factor exacerbating the other, and ultimately leading to the earlier manifestation of clinical dementia and poorer long-term antidepressant response (e.g., increased rates of depression relapse).

We and others have reported that LLD increases one’s risk of developing clinical dementia, including both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia [10, 28]. Mechanistically, LLD may contribute both directly and indirectly to the appearance of clinical AD symptoms [29]. The pathways through which this is thought to occur are multifold. First, it is well-established that LLD is associated with both chronic inflammation and HPA-axis dysfunction leading to elevated adrenal glucocorticoid production [29]. HPA-axis dysfunction in the form of hypercortisolemia may, over repeated episodes, lead to synaptodendritic and/or neuronal degeneration, resulting in hippocampal atrophy. In addition, depression-related chronic inflammation is associated with ischemia, especially in frontostriatal circuits. The combination of hippocampal atrophy, generalized ischemia, and frontostriatal dysfunction likely lowers brain reserve, which in the context of underlying AD neuropathology hastens the clinical presentation of Alzheimer’s disease. In this model, it is the reduction in reserve caused by depression-associated neurotoxocity that reduces the threshold for expression of clinical dementia [9]. While the bulk of evidence supports an indirect pathway via reduced brain or cognitive reserve, a series of rodent studies suggests the possibility of a direct relationship between depression-associated HPA-axis dysfunction and enhanced AD pathology [30, 31]. However, recent human studies have failed to find a relationship between levels of AD neuropathology and depressive symptoms [32] or chronic distress [33]. Moreover, our own recent work found no difference in beta-amyloid levels in depressed individuals with MCI and those with normal cognitive functioning, suggesting that impairment was a result of non-AD pathology [34].

Late-life depression is clearly a multifactorial disorder that is frequently accompanied by an array of neurocognitive deficits and complaints [2, 11, 29]. This study, one in a series of reports, provides further characterization and clarification of the range, type, and depth of cognitive impairments seen in depressed older adults, and uniquely does so at a single cross-sectional time point comparing individuals who are actively depressed, previously depressed but currently euthymic, and euthymic with no history of depression. The findings reinforce our previous observations that cognitive impairment in LLD is prevalent, broad-based, and appears to persist independent of the depressed individual’s current affective state.

Supplementary Material

Table 2. Comparison of Neuropsychological Test Scores Across Diagnostic Groups (Adjusting for Demographic Covariates).

| Test of Significance Across Diagnostic Groups (Hochberg adjusted p-value with Bonferroni post-hoc adjustment) |

Age (Years) | Education (Years) | Gender (%Female) | Race (%White) | CIRS-G (Total) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p-value | β (SE) | p-value | β (SE) | p-value | β (SE) | p-value | β (SE) | p-value | ||

|

| |||||||||||

|

A. Measures of Global Cognition and Premorbid Intellectual Ability:

| |||||||||||

| DRS1 | p=0.046 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −0.844 (0.15) | p<0.0001 | 1.84 (0.40) | p<0.0001 | 2.92 (2.3) | p=0.21 | 12.7 (3.2) | p<0.0001 | 0.008 (0.28) | p=0.98 |

|

| |||||||||||

| MMSE1 | p=0.005 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −1.46 (0.18) | p<0.0001 | 2.28 (0.48) | p<0.0001 | 3.01 (2.8) | p=0.28 | 12.2 (3.8) | p=0.002 | −0.113 (0.34) | p=0.74 |

|

| |||||||||||

| WTAR2 | p=0.91 | 0.408 (0.13) | p=0.002 | 2.68 (0.32) | p<0.0001 | 3.57 (1.9) | p=0.06 | 14.5 (2.8) | p<0.0001 | −0.550 (0.23) | p=0.02 |

|

| |||||||||||

|

B. Delayed Memory:

| |||||||||||

| LM | p=0.0007 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −0.675 (0.13) | p<0.0001 | 2.58 (0.36) | p<0.0001 | 5.64 (2.1) | p=0.006 | 4.60 (2.8) | p=0.10 | 0.213 (0.25) | p=0.39 |

|

| |||||||||||

| CVLT | p=0.0007 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −0.899 (0.12) | p<0.0001 | 1.07 (0.31) | p=0.0006 | 7.53 (1.8) | p<0.0001 | 5.83 (2.5) | p=0.02 | −0.017 (0.22) | p=0.94 |

|

| |||||||||||

| CVLT-R | p=0.002 (ND >MDD-E, MDD-D) | −1.25 (0.17) | p<0.0001 | 1.56 (0.45) | p=0.0005 | 10.27 (2.6) | p<0.0001 | 8.99 (3.6) | p=0.01 | −0.110 (0.31), | p=0.72 |

|

| |||||||||||

| MREY-D | p=0.06 | −0.685 (0.12) | p<0.0001 | 1.12 (0.32) | p=0.0005 | −4.56 (1.9) | p=0.01 | 3.75 (2.5) | p=0.13 | 0.118 (0.22) | p=0.60 |

|

| |||||||||||

|

C. Executive Functions:

| |||||||||||

| TRL-B | p=0.03 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −1.54 (0.23) | p<0.0001 | 2.00 (0.59) | p=0.0008 | 1.93 (3.4) | p=0.57 | 15.0 (4.6) | p=0.001 | −0.566 (0.42) | p=0.17 |

|

| |||||||||||

| EXIT | p=0.01 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −0.968 (0.13) | p<0.0001 | 1.54 (0.34) | p<0.0001 | 1.58 (2.0) | p=0.43 | 10.5 (2.7) | p=0.0002 | −0.138 (0.24) | p=0.57 |

|

| |||||||||||

| STROOP | p=0.55 | −1.11 (0.17) | p<0.0001 | 1.40 (0.45) | p=0.002 | 0.606 (2.6) | p=0.82 | 4.08 (3.5) | p=0.24 | 0.159 (0.31) | p=0.61 |

|

| |||||||||||

| WCST | p=0.19 | −0.651 (0.12) | p<0.0001 | 1.38 (0.32) | p<0.0001 | 1.83 (1.8) | p=0.32 | 4.03 (2.5) | p=0.11 | −0.423 (0.22) | p=0.06 |

|

| |||||||||||

|

D. Attention/Processing Speed:

| |||||||||||

| DSST | p=0.0007 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −1.07 (0.11) | p<0.0001 | 1.57 (0.28) | p<0.0001 | 6.64 (1.7) | p<0.0001 | 6.55 (2.3) | p=0.004 | −0.925 (0.20) | p<0.01 |

|

| |||||||||||

| GP | p=0.0007 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −1.87 (0.17) | p<0.0001 | 1.47 (0.45) | p=0.001 | 2.74 (2.6) | p=0.29 | 6.16 (3.6) | p=0.08 | −0.311 (0.31) | p=0.32 |

|

| |||||||||||

| TRL-A | p=0.008 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −1.39 (0.21) | p<0.0001 | 1.08 (0.56) | p=0.06 | 3.33 (3.3) | p=0.31 | 9.19 (4.4) | p=0.04 | −0.279 (0.39) | p=0.48 |

|

| |||||||||||

| FT | p=0.91 | −0.655 (0.10) | p<0.0001 | 0.724 (0.26) | p=0.006 | −10.6 (1.5) | p<0.0001 | 8.61 (2.1) | p<0.0001 | −0.281 (0.18) | p=0.13 |

|

| |||||||||||

|

E. Verbal Ability:

| |||||||||||

| SF | p=0.002 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −0.940 (0.10) | p<0.0001 | 1.51 (0.28) | p<0.0001 | 2.27 (1.6) | p=0.16 | 3.70 (2.2) | p=0.10 | −0.006 (0.19) | p=0.97 |

|

| |||||||||||

| MBNT | p=0.002 (ND,MDD-E>MDD-D) | −0.823 (0.12) | p<0.0001 | 1.58 (0.32) | p<0.0001 | −4.04 (1.9) | p=0.03 | 13.5 (2.6) | p<0.0001 | 0.169 (0.23) | p=0.46 |

|

| |||||||||||

| STW | p=0.64 | 0.164 (0.12) | p=0.16 | 2.89 (0.31) | p<0.0001 | 3.70 (1.8) | p=0.04 | 11.4 (2.4) | p<0.0001 | 0.125 (0.21) | p=0.56 |

|

| |||||||||||

| LF | p=0.91 | −0.190 (0.10) | p=0.05 | 1.70 (0.26) | p<0.0001 | 2.54 (1.5) | p=0.10 | 5.90 (2.1) | p=0.006 | −0.354 (0.19) | p=0.06 |

|

| |||||||||||

|

F. Visuospatial Ability:

| |||||||||||

| BD | p=0.0007 (ND>MDD-E, MDD-D) | −0.683 (0.10) | p<0.0001 | 1.12 (0.27) | p<0.0001 | −1.78 (1.5) | p=0.25 | 8.29 (2.1) | p<0.0001 | −0.379 (0.19) | p=0.04 |

|

| |||||||||||

| CDT | p=0.03 (ND,MDD-E>MDD-D) | −0.822 (0.12) | p<0.0001 | 1.33 (0.32) | p<0.0001 | 3.95 (1.9) | p=0.04 | 3.26 (2.6) | p=0.20 | 0.145 (0.22) | p=0.52 |

|

| |||||||||||

| MREY-C | p=0.91 | −0.461 (0.14) | p=0.0008 | 0.648 (0.36) | p=0.07 | −2.99 (2.1) | p=0.16 | 5.02 (2.8) | p=0.08 | 0.165 (0.25) | p=0.52 |

|

| |||||||||||

| SD | p=0.91 | −0.548 (0.10) | p<0.0001 | 0.754 (0.28) | p=0.007 | 2.21 (1.6) | p=0.17 | 5.54 (2.2) | p=0.01 | −0.468 (0.19) | p=0.02 |

Measure of Global Cognition.

Measure of Premorbid Intellectual Ability.

N.B. We report beta weights for each covariate from the standard regression (ANCOVA) models.

Abbreviations: Measures of global cognition and premorbid intellectual ability: Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS), Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), and Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). Measures of delayed memory: Logical Memory (LM) subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale, free recall (CVLT) and recognition (CVLT-R) of the California Verbal Learning Test, California Verbal Learning Test recognition memory (CVLT-R) and delayed copy of the Modified Rey-Osterrieth Figure (MREY-D). Measures of executive functioning: Trail Making Test Part B (TRL-B), Executive Interview (EXIT), Stroop Color-Word Inhibition Test (Stroop), and Wisconsin Card-Sorting Test (WCST). Measures of attention/processing speed: Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), Grooved Pegboard Test (GP), Trail Making Test Part A (TRL-A), and Finger Tapping Test (FT). Measures of verbal ability: Semantic Fluency Test (SF), Modified Boston Naming Test (MBNT), Spot the Word Test (STW), and Letter Fluency Test (LF). Measures of visuospatial ability: Block Design Test (BD), Clock Drawing Test (CDT), immediate copy of the Modified Rey-Osterrieth Figure (MREY-C), and Simple Drawings Test (SD).

Hypothesis A: MDD-D and MDD-E participants would perform significantly worse than ND participants on baseline neuropsychological tests measuring global cognition, episodic memory, attention/processing speed, verbal ability, and visuospatial ability.

Hypothesis B: Differences in cognition between ND and depressed (MDD-D, MDD-E) participants would be most pronounced within the domain of attention/processing speed.

Hypotheses C & D: Participants in the MDD-E group would perform better than participants in the MDD-D group on measures of executive functioning, but both groups would perform worse than ND participants.

Acknowledgments and Sources of Support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 MH072947 & R01 MH080240 (MAB), P30 MH090333 (ACISR), UL1 TR000005 (CTSI) (CFR, SJA, MAB), the UPMC Endowment in Geriatric Psychiatry (CFR), P50 AG005133 (JTB, MAB),and R01 MH084921(SJA).

Works Cited

- [1].Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Butters MA, Whyte EM, Nebes RD, Begley AE, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, Zmuda MD, Bhalla R, Meltzer CC, Pollock BG, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Becker JT. The nature and determinants of neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:587–595. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sheline YI, Barch DM, Garcia K, Gersing K, Pieper C, Welsh-Bohmer K, Steffens DC, Doraiswamy PM. Cognitive function in late life depression: relationships to depression severity, cerebrovascular risk factors and processing speed. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nebes RD, Butters MA, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Zmuda MD, Houck PR, Reynolds CF., 3rd Decreased working memory and processing speed mediate cognitive impairment in geriatric depression. Psychol Med. 2000;30:679–691. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lockwood KA, Alexopoulos GS, van Gorp WG. Executive dysfunction in geriatric depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1119–1126. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Baudic S, Tzortzis C, Barba GD, Traykov L. Executive deficits in elderly patients with major unipolar depression. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:195–201. doi: 10.1177/0891988704269823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Elderkin-Thompson V, Kumar A, Bilker WB, Dunkin JJ, Mintz J, Moberg PJ, Mesholam RI, Gur RE. Neuropsychological deficits among patients with late-onset minor and major depression. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18:529–549. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6177(03)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rapp MA, Dahlman K, Sano M, Grossman HT, Haroutunian V, Gorman JM. Neuropsychological differences between late-onset and recurrent geriatric major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:691–698. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Koenig AM, Bhalla RK, Butters MA. Cognitive functioning and late-life depression. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20:461–467. doi: 10.1017/S1355617714000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF., 3rd Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:329–335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Butters MA, Becker JT, Nebes RD, Zmuda MD, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Reynolds CF., 3rd Changes in cognitive functioning following treatment of late-life depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1949–1954. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Doraiswamy PM, Krishnan KR, Oxman T, Jenkyn LR, Coffey DJ, Burt T, Clary CM. Does antidepressant therapy improve cognition in elderly depressed patients? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:M1137–1144. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.12.m1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bhalla RK, Butters MA, Mulsant BH, Begley AE, Zmuda MD, Schoderbek B, Pollock BG, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Becker JT. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits in the remitted state of late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:419–427. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203130.45421.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nebes RD, Pollock BG, Houck PR, Butters MA, Mulsant BH, Zmuda MD, Reynolds CF., 3rd Persistence of cognitive impairment in geriatric patients following antidepressant treatment: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial with nortriptyline and paroxetine. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Murphy CF, Alexopoulos GS. Longitudinal association of initiation/perseveration and severity of geriatric depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:50–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee JS, Potter GG, Wagner HR, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Steffens DC. Persistent mild cognitive impairment in geriatric depression. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19:125–135. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bhalla RK, Butters MA, Becker JT, Houck PR, Snitz BE, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Raina KD, DeKosky ST, Reynolds CF., 3rd Patterns of mild cognitive impairment after treatment of depression in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:308–316. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318190b8d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GK, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reynolds CF, 3rd, Butters MA, Lopez O, Pollock BG, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, Lenze EJ, Holm M, Rogers JC, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Begley A, Anderson S, Karp JF, Miller MD, Whyte EM, Stack J, Gildengers A, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kaufer DI, Kamboh MI, DeKosky ST. Maintenance treatment of depression in old age: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the efficacy and safety of donepezil combined with antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:51–60. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Barch DM, D’Angelo G, Pieper C, Wilkins CH, Welsh-Bohmer K, Taylor W, Garcia KS, Gersing K, Doraiswamy PM, Sheline YI. Cognitive improvement following treatment in late-life depression: relationship to vascular risk and age of onset. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:682–690. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318246b6cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].First MB. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders : SCID-II. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Miller M, Paradis C, Houck P, Mazumda S, Stac J, Rifai A, Mulsant B, Reynolds C. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Research. 1992;41:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960:52–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Blakesley RE, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, Houck PR, Tang G, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Butters MA. Comparisons of methods for multiple hypothesis testing in neuropsychological research. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:255–264. doi: 10.1037/a0012850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].La Rue A. Patterns of performance on the Fuld Object Memory Evaluation in elderly inpatients with depression or dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989;11:409–422. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dybedal GS, Tanum L, Sundet K, Gaarden TL, Bjolseth TM. Neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Front Psychol. 2013;4:381. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Koehler S, Thomas AJ, Barnett NA, O’Brien JT. The pattern and course of cognitive impairment in late-life depression. Psychol Med. 2010;40:591–602. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sweet RA, Hamilton RL, Butters MA, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Lewis DA, Lopez OL, DeKosky ST, Reynolds CF., 3rd Neuropathologic correlates of late-onset major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:2242–2250. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Butters MA, Young JB, Lopez O, Aizenstein HJ, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF, 3rd, DeKosky ST, Becker JT. Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:345–357. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.3/mabutters. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dong H, Csernansky JG. Effects of stress and stress hormones on amyloid-beta protein and plaque deposition. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:459–469. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rothman SM, Mattson MP. Adverse stress, hippocampal networks, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2009;12:56–70. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8107-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wilson RS, Capuano AW, Boyle PA, Hoganson GM, Hizel LP, Shah RC, Nag S, Schneider JA, Arnold SE, Bennett DA. Clinical-pathologic study of depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in old age. Neurology. 2014 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Li Y, Bennett DA. Chronic distress, age-related neuropathology, and late-life dementia. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:47–53. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000250264.25017.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Diniz BS, Sibille E, Ding Y, Tseng G, Aizenstein HJ, Lotrich F, Becker JT, Lopez OL, Lotze MT, Klunk WE, Reynolds CF, Butters MA. Plasma biosignature and brain pathology related to persistent cognitive impairment in late-life depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.