Abstract

Curcumin, the medically active component from Curcuma longa (Turmeric), is widely used to treat inflammatory diseases. Protein interaction network (PIN) analysis was used to predict its mechanisms of molecular action. Targets of curcumin were obtained based on ChEMBL and STITCH databases. Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) were extracted from the String database. The PIN of curcumin was constructed by Cytoscape and the function modules identified by gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis based on molecular complex detection (MCODE). A PIN of curcumin with 482 nodes and 1688 interactions was constructed, which has scale-free, small world and modular properties. Based on analysis of these function modules, the mechanism of curcumin is proposed. Two modules were found to be intimately associated with inflammation. With function modules analysis, the anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin were related to SMAD, ERG and mediation by the TLR family. TLR9 may be a potential target of curcumin to treat inflammation.

Abbreviations: ETS, erythroblast transformation-specific; GO, gene ontology; IFNs, interferons; IL, interleukin; JAK-STAT, Janus kinase-STAT; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MCODE, molecular complex detection; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; PIN, protein interaction network; PPIs, protein–protein interactions; STATs, signal transducer and activator of transcription complexes; TLR, toll-like receptor

KEY WORDS: Curcumin, Protein interaction network, Module, Anti-inflammatory, Molecular mechanism, Gene ontology enrichment analysis, Molecular complex detection, Cytoscape

Graphical abstract

The anti-inflammatory mechanism of curcumin is elucidated by module-based protein interaction network at the molecular level. This study provides reference for curcumin clinical application and further drug development. Module-network and GO analysis also provide an efficient way to illustrate the molecular mechanism of anti-inflammatory action for curcumin.

1. Introduction

Curcumin, derived from Curcuma longa (Turmeric), is not only known as a spice that gives a yellow color to food, but also a traditional medicine that has been widely used particularly for treating various malignant diseases, arthritis, allergies, Alzheimer's disease, and other inflammatory illnesses1, 2. The anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin have been shown in clinical and experimental studies3, 4, 5, 6, and analogs and derivatives of curcumin with anti-inflammatory biological activity have been developed7, 8. To make new derivatives as effective as possible, the modified structure should be based on the action targets. Therefore, research into the molecular mechanism of curcumin is important for both new drug design and clinical treatment. Although the anti-inflammatory mechanism of curcumin has been partly unraveled7, 8, 9, it needs to be further clarified at the molecular level.

Proteins perform a vast array of functions within living organisms, but they rarely act alone. Signaling proteins often form dynamic protein–protein interaction (PPI) complexes to achieve multi-functionality and constitute cellular signaling pathways and cell morphogenesis10, 11. PPIs are pivotal for many biological processes12, 13, 14, 15. The gene ontology (GO) project16 is a collaborative effort to construct ontologies which facilitate biologically meaningful annotation of gene products. It provides a collection of well-defined biological terms, spanning biological processes, molecular functions and cellular components. GO enrichment is a common statistical method used to identify shared associations between proteins and annotations to GO. Module-network and GO analysis may provide an efficient way to illustrate the molecular mechanism of anti-inflammatory action for curcumin.

This paper aims to further elucidate the anti-inflammatory molecular mechanism of curcumin, and provide reference for its clinical application and further drug development. A network pharmacology approach was applied to analyze the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of curcumin, as a network analysis approach has the advantage of evaluating the pharmacological effect of a drug as a whole at the molecular level16. The protein interaction networks (PINs) of curcumin were constructed by Cytoscape, and the properties of the scale-free, small-world network and module were analyzed based on topological parameters. Functional modules were identified by gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis based on molecular complex detection (MCODE).

2. Methods

2.1. Network construction

Targets of curcumin were extracted from ChEMBL (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/#) and STITCH4.0 (http://stitch.embl.de/). ChEMBL17 is a manually curated chemical database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties whose data are manually abstracted on a regular basis from the primary published literature, then further curated and standardized. STITCH18 is a database of protein–chemical interactions that integrates many sources of experimental and manually-curated evidence with text-mining information and interaction predictions.

The PPI information was obtained from the online databases of String 9.1 (http://string-db.org) which was used to retrieve the predicted interactions for the targets19. All associations available in String are provided with a probabilistic confidence score. Targets with a confidence score greater than 0.7 were selected to construct the PPI network.

2.2. Network analysis

Topological properties have become very popular to gain an insight into the organization and the structure of the resultant large complex networks20, 21, 22. Therefore, topological parameters such as the clustering coefficient, connected components, degree distribution and average shortest path were analyzed by Network Analyzer17 in Cytoscape software. Compared with the random network, the properties of scale-free, small world and modularity of the PIN were also investigated based on the topological parameters.

The MCODE was used to further divide the PPI into modules, using a cutoff value for the connectivity degree of nodes (proteins in the network) greater than 3. The algorithm has the advantage over other graph clustering methods of having a directed mode that allows fine-tuning of clusters of interest without considering the rest of the network and allows examination of cluster interconnectivity, which is relevant for protein networks23. Based on the identified modules, GO functional annotation and enrichment analysis were performed using the BinGO24 plugin in Cytoscape with a threshold of P<0.05 based on a hypergeometric test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Construction of the network

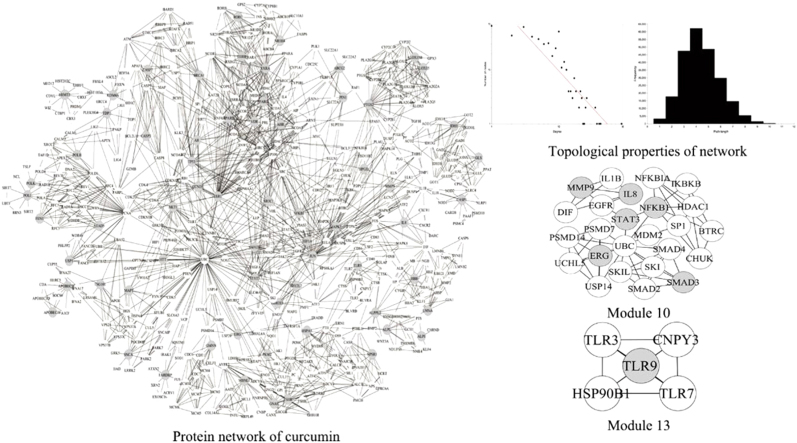

Ten human proteins from STITCH 4.0 and 68 human proteins from ChEMBL (data accessed in August 2014) were extracted. 67 human proteins as curcumin targets were obtained after removing a repeat protein. The binding affinities (IC50) of ALPI and TLR9 were, respectively, 100 and 8.36 μmol/L. The IC50 values of the remaining targets were not available because curcumin would have inhibited or activated other proteins25, 26. Information on the targets is listed in Table 1. The PPIs of the targets were imported in Cytoscape27, union calculations were carried out and the duplicated edges of PPIs were removed using Advanced Network Merge28 Plugins, and the largest connected subgraph was selected as the PIN of curcumin, which included 482 nodes and 1688 edges, as shown in Fig. 1. The nodes represent proteins and the edges indicate their relations. The gray nodes represent seed nodes and the others are nodes that interact with seed nodes. Due to limits of the current studies, some human protein interactions are still unclear. As a result, the network constructed for this research is not comprehensive and the largest connected subgraph was selected for further analysis.

Table 1.

Proposed curcumin targets.

| Target | UniProt ID | Target | UniProt ID | Target | UniProt ID | Target | UniProt ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCG2a | Q9UNQ0 | AR | P10275 | HSD17B10 | Q99714 | POLB | P06746 |

| AKT1a | P31749 | ATAD5 | Q96QE3 | HSPA5 | P11021 | POLI | Q9UNA4 |

| CASP3a | P42574 | BACE1 | P56817 | HTT | P42858 | POLK | Q9UBT6 |

| CCND1a | P24385 | BAZ2B | Q9UIF8 | IDH1 | O75874 | PPARD | Q03181 |

| HMOX1a | P09601 | BRCA1 | P38398 | IL-8 | P10145 | RORC | P51449 |

| JUNa | P05412 | CASP1 | P29466 | KCNH2 | Q12809 | RXRA | P19793 |

| MMP9a | P14780 | CASP7 | P55210 | KDM4A | O75164 | SMAD3 | P84022 |

| PPARGb | P37231 | CYP3A4 | P08684 | KDM4DL | B2RXH2 | SNCA | P37840 |

| PTGS2a | P35354 | EHMT2 | Q96KQ7 | LMNA | P02545 | TARDBP | Q13148 |

| STAT3a | P40763 | ERG | P11308 | MAPK1 | P28482 | TDP1 | Q9NUW8 |

| AHR | P35869 | ESR1 | P03372 | MAPT | P10636 | THRB | P10828 |

| ALDH1A1 | P00352 | FEN1 | P39748 | MBNL1 | Q9NR56 | TLR9 | Q9NR96 |

| ALOX12 | P18054 | GAA | P10253 | MLL | Q03164 | TP53 | P04637 |

| ALOX15 | P16050 | GBA | P04062 | NFE2L2 | Q16236 | TSG101 | Q99816 |

| ALOX15B | O15296 | GLS | O94925 | NFKB1 | P19838 | TSHR | P16473 |

| ALPI | P09923 | GMNN | O75496 | NPSR1 | Q6W5P4 | USP1 | O94782 |

| ALPL | P05186 | GNAS | P63092 | NR1H4 | Q96RI1 | VDR | P11473 |

| ALPPL2 | P10696 | HBB | P68871 | NR3C1 | P04150 | ||

| APOBEC3F | Q8IUX4 | HIF1A | Q16665 | PIN1 | Q13526 | ||

| APOBEC3G | Q9HC16 | HPGD | P15428 | PKM2 | P14618 |

Targets were obtained from STITCH.

Targets were extracted from both ChEMBL and STITCH. The remaining targets were obtained from ChEMBL.

Figure 1.

The protein network of curcumin. The nodes and edges indicate the proteins and their relationships. The gray nodes represent seed nodes and the white ones are nodes that interact with the seed nodes.

3.2. Network analysis

3.2.1. Topological analysis

All the topological parameters were calculated, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The topological parameters of the protein interaction network of curcumin.

| Parameter | Network |

|

|---|---|---|

| PIN of curcumin | Random network | |

| Clustering coefficient | 0.641 | 0.016 |

| Connected component | 1 | 1 |

| Network diameter | 11 | 4 |

| Network centralization | 0.165 | 0.017 |

| Shortest path | 231,842 (100%) | 231,842 (100%) |

| Characteristic path length | 4.394 | 3.390 |

| Network heterogeneity | 0.995 | 0.376 |

The connected component is 1, indicating that the network has no other subgraphs. The network diameter is the greatest distance between any pair of vertices. Network centralization is a network index that measures the degree of dispersion of all node centrality scores in a network. Network heterogeneity measures the degree of uneven distribution of the network.

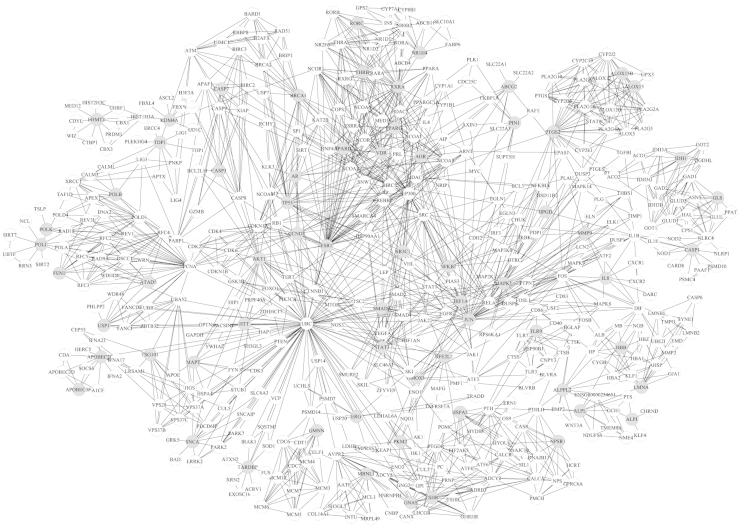

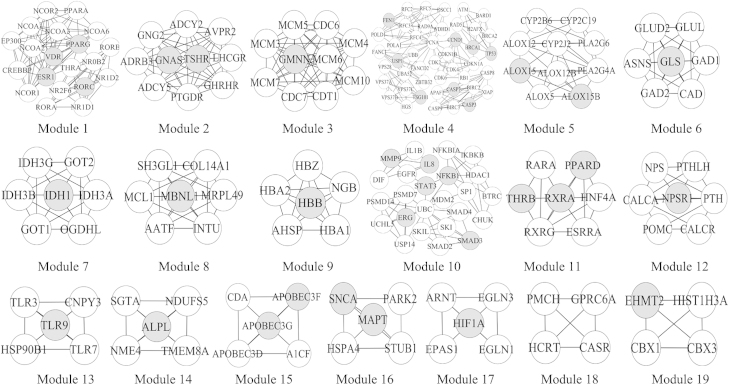

Degree distribution was computed by counting the number of connections between various proteins of the network29, 30. As shown in Fig. 2A, the degree distribution of the PIN of curcumin followed the power law distribution and the equation is y=218.67x−1.359. The PIN of curcumin is a scale-free network.

Figure 2.

Topological properties of the network. (A) Degree distribution of the curcumin network; (B) shortest path length distribution of the curcumin network.

Average shortest path refers to the average density of the shortest paths between all pairs of nodes29, 30. As shown in Fig. 2B, network path length was mostly concentrated in steps 3–5. The shortest path length between any two proteins was 4.394. This meant that most proteins were very closely linked and the PIN of curcumin was a small world network.

Clustering coefficient refers to the average density of the node neighborhoods29, 30. The higher the clustering coefficient, the more modular the network is. Compared with a random network whose number of nodes and edges are the same as the PIN of curcumin, the PIN clustering coefficient for curcumin was higher. This indicates that the PIN of curcumin possesses the property of modularity. This result suggests that the network possesses the scale-free property, a small world property and modular properties.

3.2.2. Clustering and GO enrichment analysis

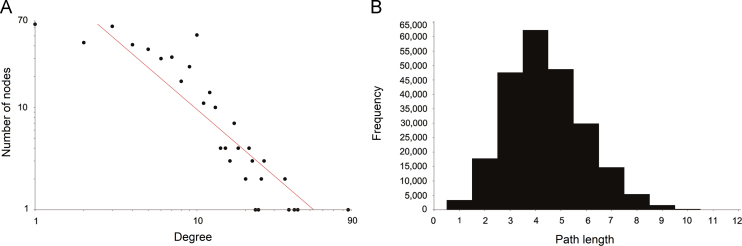

As shown in Fig. 3, 19 modules were identified from the network through the MCODE algorithm. The gray nodes indicate seed nodes and the others are nodes that interact with seed nodes.

Figure 3.

Modules in the PIN of curcumin. With the MCODE algorithm, 19 modules were extracted from the network. The gray nodes present seed nodes and the white ones are nodes that interact with the seed nodes.

The results of functional enrichment analysis using BinGO are shown in Table 3. The result shows that curcumin has pharmacodynamic interactions with several biological processes, including regulation of transcription, cell-cycle processing, negative regulation of thrombin, hydrogen peroxide metabolic processing, and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Module 10 and module 13 are related to anti-inflammatory actions.

Table 3.

GO biological process terms of the modules.

| Module | GO term | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | Transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter | 7.6587×10−32 |

| Module 2 | G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway, coupled to cyclic nucleotide second messenger | 3.8329×10−20 |

| Module 3 | M/G1 transition of mitotic cell cycle | 7.7133×10−27 |

| Module 4 | Response to DNA damage stimulus | 2.0766×10−32 |

| Module 5 | Fatty acid derivative metabolic process | 2.0128×10−16 |

| Module 6 | Glutamine family amino acid catabolic process | 5.7668×10−18 |

| Module 7 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | 1.6501×10−13 |

| Module 8 | Negative regulation of superoxide anion generation | 2.30×10−4 |

| Module 9 | Hydrogen peroxide catabolic process | 1.5518×10−8 |

| Module 10 | Cellular response to growth factor stimulus | 4.6078×10−16 |

| Module 11 | Transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter | 6.9789×10−16 |

| Module 12 | G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway | 2.3039×10−10 |

| Module 13 | Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 5.23×10−7 |

| Module 14 | Cementum mineralization | 1.31×10−4 |

| Module 15 | DNA cytosine deamination | 2.1272×10−11 |

| Module 16 | Negative regulation of thrombin receptor signaling pathway | 1.64×10−4 |

| Module 17 | Regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter in response to hypoxia | 4.5178×10−16 |

| Module 18 | G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway | 6.04×10−5 |

| Module 19 | Chromatin organization | 4.23×10−5 |

P value is the probability of obtaining the observed effect, a very small P value indicates that the observed effect is very unlikely to have arisen purely by chance, and therefore provides evidence against the null hypothesis.

Module 10 contains proteins such as interleukin (IL)-8, Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), signal transducer and activator of transcription complex (STAT)3, SMAD3 and ERG. IL-8 is a key indicator of localized inflammation31. NF-κB is a key signaling molecule in the elaboration of the inflammatory response. STAT3 is activated in response to various cytokines and growth factors including IL-6 and IL-10. Curcumin was previously reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory actions by decreasing IL-8 levels32, acting as an NF-κB inhibitor25, 26 and suppressing STAT333. Therefore, the predicted results based on network analysis were consistent with these previous findings. The expression of SMAD3 is related to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)34. It has been reported that curcumin demonstrates anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting MAPK35. Consequently, the anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin would be related to the predicted interaction with SMAD3. ERG is a member of the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) family of transcription factors which regulate inflammation36. ERG also has been shown to interact with c-Jun (activated through double phosphorylation by the JNK pathway) which contributes to inflammation37. At the same time, curcumin was anti-inflammatory by inhibiting JNK activity32, indicating that the anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin would be related to ERG. Hence, the analysis of module 10 indicated that the anti-inflammatory actions of curcumin may be associated with SMAD3 and ERG.

Module 13 is closely related to the toll-like receptor (TLR) family, including TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9. TLR338 leads to the activation of IRF3, which ultimately induces the production of type I interferons (IFNs). IFNs activate STATs, suggesting that the Janus kinase-STAT (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway was initiated39. There is evidence that the JAK-STAT pathway is involved in the anti-inflammatory reaction40. TLR7 and TLR9 also led to activation of the cells that initiated pro-inflammatory reactions resulting the production of cytokines, such as, type-I interferon41. Moreover, TLR9 was the seed node and the binding affinity (IC50) with curcumin is 8.36 μmol/L. This indicates that TLR9 may be a potential target of curcumin to treat inflammation and curcumin may exert anti-inflammatory properties through the TLR family.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the PIN of curcumin possesses scale-free, small world properties and modular properties based on analysis of its topological parameters. A module-based network analysis approach was proposed to highlight the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of curcumin. The anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin may be related to SMAD and ERG, and mediated by the TLR family. TLR9 may be a potential target of curcumin to treat inflammation. However, further experiments are needed to confirm these conclusions.

Although the present analysis is restricted to in silico analysis, this study provides an efficient way to elucidate possible mechanisms of curcumin, and provides reference for its clinical application and further drug development.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81403103); Chinese Medicine Resources (Sichuan Province) Youth Science and Technology Innovation Team (Grant No. 2015TD0028); Sichuan Province Science and Technology Support Plan (Grant No. 2014SZ0156); Sichuan Province Education Department Project (Grant No. 2013SZB0781).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association

Contributor Information

Wan Liao, Email: liaowan2011@126.com.

Chaomei Fu, Email: chaomeifu@126.com.

References

- 1.Leitman I.M. Curcumin for the prevention of acute lung injury in sepsis: is it more than the flavor of the month? J Surg Res. 2012;176:e5–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.11.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yilmaz Savcun G., Ozkan E., Dulundu E., Topaloglu U., Sehirli A.O., Tok O.E. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin against hepatorenal oxidative injury in an experimental sepsis model in rats. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:507–515. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2013.76390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menon V.P., Sudheer A.R. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:105–125. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemeida R.A., Mohafez O.M. Curcumin attenuates methotraxate-induced hepatic oxidative damage in rats. J Egypt Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;20:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacob A., Wu R., Zhou M., Wang P. Mechanism of the anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin: PPAR-γ activation. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:89369–89373. doi: 10.1155/2007/89369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar P., Padi S.S., Naidu P.S., Kumar A. Possible neuroprotective mechanisms of curcumin in attenuating 3-nitropropionic acid-induced neurotoxicity. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2007;29:19–25. doi: 10.1358/mf.2007.29.1.1063492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y., Liang D., Dong L., Ge X., Xu F., Chen W. Anti-inflammatory effects of novel curcumin analogs in experimental acute lung injury. Respir Res. 2015;16:43–55. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao C., Zhang Y., Zou P., Wang J., He W., Shi D. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a novel class of curcumin analogs as anti-inflammatory agents for prevention and treatment of sepsis in mouse model. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9:1663–1678. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S75862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fajardo A.M., Piazza G.A. Anti-inflammatory approaches for colorectal cancer chemoprevention. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G59–G70. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00101.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh J.T., Binari R., Gocha T., Dasgupta R., Perrimon N. PAPTi: a peptide aptamer interference toolkit for perturbation of protein–protein interaction networks. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1156. doi: 10.1038/srep01156. –43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T., Ming Z., Xiaochun W., Hong W. Rab7: role of its protein interaction cascades in endo-lysosomal traffic. Cell Signal. 2011;23:516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maetschke S.R., Simonsen M., Davis M.J., Ragan M.A. Gene ontology-driven inference of protein–protein interactions using inducers. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:69–75. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology, the gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Q.C., Petrey D., Deng L., Qiang L., Shi Y., Thu C.A. Structure-based prediction of protein–protein interactions on a genome-wide scale. Nature. 2012;490:556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature11503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren Z., Wang X., Wang S., Zhai C., He Y., Zhang Y. Mechanism of action of salvianolic acid B by module-based network analysis. Biomed Mater Eng. 2014;24:1333–1340. doi: 10.3233/BME-130936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janga S.C., Tzakos A. Structure and organization of drug-target networks: insights from genomic approaches for drug discovery. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:1536–1548. doi: 10.1039/B908147j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaulton A., Bellis L.J., Bento A.P., Chambers J., Davies M., Hersey A. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1100–D1107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn M., Szklarczyk D., Pletscher-Frankild S., Blicher T.H., von Mering C., Jensen L.J. STITCH 4: integration of protein–chemical interactions with user data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D401–D407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franceschini A., Szklarczyk D., Frankild S., Kuhn M., Simonovic M., Roth A. STRING v9.1: protein–protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albert R. Scale-free networks in cell biology. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4947–4957. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almaas E. Biological impacts and context of network theory. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:1548–1558. doi: 10.1242/jeb.003731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barabasi A.L., Oltvai Z.N. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bader G.D., Hogue C.W. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003;4:2–28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin W., Wang J., Zhu T., Yuan B., Ni H., Jiang J. Anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in experimental spinal cord injury in rats. Inflamm Res. 2014;63:381–387. doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0710-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kloesch B., Becker T., Dietersdorfer E., Kiener H., Steiner G. Anti-inflammatory and apoptotic effects of the polyphenol curcumin on human fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;15:400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assenov Y., Ramirez F., Schelhorn S.E., Lengauer T., Albrecht M. Computing topological parameters of biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:282–284. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manke T., Demetrius L., Vingron M. Lethality and entropy of protein interaction networks. Genome Inform. 2005;16:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Przulj N. Biological network comparison using graphlet degree distribution. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:e177–e183. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Estrada E. Virtual identification of essential proteins within the protein interaction network of yeast. Proteomics. 2006;6:35–40. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlahopoulos S., Boldogh I., Casola A., Brasier A.R. Nuclear factor-κB-dependent induction of interleukin-8 gene expression by tumor necrosis factor alpha: evidence for an antioxidant sensitive activating pathway distinct from nuclear translocation. Blood. 1999;94:1878–1889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klawitter M., Quero L., Klasen J., Gloess A.N., Klopprogge B., Hausmann O. Curcuma DMSO extracts and curcumin exhibit an anti-inflammatory and anti-catabolic effect on human intervertebral disc cells, possibly by influencing TLR2 expression and JNK activity. J Inflamm. 2012;9:29–42. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shehzad A., Ha T., Subhan F., Lee Y.S. New mechanisms and the anti-inflammatory role of curcumin in obesity and obesity-related metabolic diseases. Eur J Nutr. 2011;50:151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross K.R., Corey D.A., Dunn J.M., Kelley T.J. SMAD3 expression is regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-1 in epithelial and smooth muscle cells. Cell Signal. 2007;19:923–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patwardhan R.S., Checker R., Sharma D., Kohli V., ,, Priyadarsini K.I., Sandur S.K. Dimethoxycurcumin, a metabolically stable analogue of curcumin, exhibits anti-inflammatory activities in murine and human lymphocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:642–657. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murakami K., Mavrothalassitis G., Bhat N.K., Fisher R.J., Papas T.S. Human ERG-2 protein is a phosphorylated DNA-binding protein—a distinct member of the ets family. Oncogene. 1993;8:1559–1566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verger A., Buisine E., Carrere S., Wintjens R., Flourens A., Coll J. Identification of amino acid residues in the ETS transcription factor Erg that mediate Erg-Jun/Fos-DNA ternary complex formation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17181–17189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexopoulou L., Holt A.C., Medzhitov R., Flavell R.A. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Platanias L.C. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Busch-Dienstfertig M., Gonzalez-Rodriguez S. IL-4 JAK-STAT signaling, and pain. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e27638. doi: 10.4161/jkst.27638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]