Abstract

This paper reports investigations into the preparation and characterization of surface molecularly imprinted nanoparticles (SMINs) designed to adhere to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). Imprinted nanoparticles were prepared by the inverse microemulsion polymerization method. A fraction of Lpp20, an outer membrane protein of H. pylori known as NQA, was chosen as template and modified with myristic acid to facilitate its localization on the surface of the nanoparticles. The interaction between these SMINs with the template NQA were evaluated using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), change in zeta potential and fluorescence polarization (FP). The results were highly consistent in demonstrating a preferential recognition of the template NQA for SMINs compared with the control nanoparticles. In vitro experiments also indicate that such SMINs are able to adhere to H. pylori and may be useful for H. pylori eradication.

Key words: Surface molecularly imprinted nanoparticles, Epitope imprinting, NQA, Lpp20, Helicobacter pylori binding

Graphical abstract

Surface molecularly imprinted nanoparticles (SMINs) designed to bind to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) have been prepared and characterized. Surface plasmon resonance, fluorescence polarization and changes in zeta potential were used to evaluate recognition between template and SMINs. In vitro experiments indicate nanoparticles imprinted with a amphiphilic template preferentially recognize H. pylori. SMINs appear to be a novel drug delivery system for eradication of H. pylori.

1. Introduction

During recent decades, mucoadhesive drug delivery systems (MDDS) for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication have been frequently reported. The ability of MDDS to adhere to the mucus layer prolongs their retention time in the gastrointestinal tract and thereby enables the loaded drug to interact with H. pylori for a longer time. However, this non-specific adhesion is affected not only by varying turnover time and composition of mucus but also by how the mucoadhesive polymer used to make MDDS responds to changes in pH and physiological or disease conditions. Such variability seriously limits the application of this technique1. This paper reports the results of an investigation into the preparation and characterization of surface molecularly imprinted nanoparticles (SMINs) designed to bind to H. pylori.

Molecular imprinting involves the synthesis of polymers in the presence of a template molecule. The process produces polymers with surface binding sites that complement those of the template in terms of its size, shape and functional group orientation2. Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) have been widely recognized as promising alternatives to enzymes, antibodies and natural receptors due to their specificity, robustness and reusability3. However, most of the successful examples are imprinted with low molecular weight compounds while imprinting with larger molecules such as peptides and proteins, or with complex systems such as viruses and cells is still in its infancy. According to Kryscio et al.4, it is now evident that the general design principles of low molecular weight MIPs do not apply to the macromolecular regime. The monomers commonly employed in MIPs significantly alter the template conformation prior to polymerization and compromise the specific recognition of the template.

Three main approaches have been developed for protein imprinting2: (1) Bulk imprinting where the protein template is wholly imprinted in the bulk of the polymer matrix and is bound as a whole molecule by functional monomers; (2) surface imprinting where the protein template is partially imprinted in the bulk of the polymer matrix and binding sites are at or close to the surface; and (3) epitope imprinting where only a small part of the protein is imprinted but the resulting MIPs are able to recognize the whole protein. In bulk imprinting, the binding sites of the template proteins tend to be restricted within the polymer matrix and are only exposed by grinding the matrix. As a result, surface and epitope imprinting have attracted increasing interest.

To mimic the genuine “antigen-antibody” interaction, it is important that well-designed imprints are evenly distributed on the surface of SMINs. To achieve this goal, Zeng et al.5 initiated a so-called “general strategy for surface imprinting” in which a hydrophilic peptide could be located at the surface of nanoparticles after modification. We have used this approach in preparing SMINs.

Lpp20 is a conserved 20 kDa outer membrane lipoprotein antigen specifically expressed by all strains of H. pylori that has been shown to act as a potential target for vaccine and pharmacotherapy6, 7. In our laboratory, an exposed antigenic domain of Lpp20 (amino acids 83–115 from the N-terminus, abbreviated as NQA) was imprinted on the surface of nanoparticles. According to research by our group8 and Zeng et al.5, “surface imprinting” is more likely to be achieved during an inverse mini-emulsion polymerization process when the template molecules are amphiphilic. Based on this consideration, the hydrophilic NQA was modified with a long hydrocarbon tail (from myristic acid (Myr)) and used as the template to imprint surface capture sites for the entire Lpp20 lipoprotein. Such an epitope imprinting strategy has been previously used to capture Staphylococus aureus9, 10, 11.

Some reports have argued that one of the technical challenges in molecular imprinting of proteins relates to the quantitation of the resulting binding. In many cases, determination of the extent of binding is unreliable and leads to unconvincing results12. Therefore, newly designed approaches to quantitation are required. In the current study, several approaches to assess protein–protein interactions or the bioadhesive properties of polymers including surface plasmon resonance (SPR), fluorescence polarization (FP) and changes in zeta potential were applied to evaluate the binding of the template to the MIPs. Preliminary in vitro studies were also performed to evaluate the efficacy of the MIPs to specifically adhere to H. pylori. Further studies on therapeutic drug delivery by means of this type of SMINs are underway.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Acrylamide, N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (BisAM), ammonium persulfate (APS) and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) were purchased from Aladdin Reagents Co., Ltd. (Shanghai). 5-Carboxyfluoresccein (FAM) and dioctyl sulfosuccinate sodium salt (AOT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Brij 30 was supplied by J&K Chemicals. NQA (MW 3582 Da, pI 9.5), myristic acid modified NQA (Myr-NQA), and FAM modified NQA (FAM-NQA) were obtained from GL Biochem. The Biacore sensor chip CM5 and HBS-EP buffer were purchased from GE Healthcare. All other chemicals and solvents were analytical grade and used as received. Deionized water was produced by a Milli-Q integral water purification system (Millipore).

2.2. Cell lines and H. pylori strain

Human gastric epithelial (AGS) cells were obtained from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institute for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Cells were maintained in Ham's F-12 medium (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal calf serum and cultured in incubators maintaining 5% CO2 under microaerophilic conditions at 37 °C. H. pylori strain SS1 was obtained from the Institute of Gastrointestinal Disease, Yan Chai Hospital.

2.3. Preparation of nanoparticles

Myr-NQA imprinted nanoparticles (Myr-NQA-MINs) were prepared as previously reported with some modifications5. Briefly, a monomer solution was formed by dissolving acrylamide (0.45 g) and BisAM (0.13 g) in 1.0 mL water. Myr-NQA (8.0 mg) was added to the solution and magnetically stirred to facilitate effective monomer-template interaction. Subsequently, 1.0 mL of this monomer-template solution was added dropwise to a deoxygenated mixture of hexane (21.5 mL), AOT (0.70 g) and Brij 30 (1.50 g), and stirred continuously for 30 min. Finally, APS solution (10% w/v, 50 μL) followed by TEMED (25 μL) were added to the mixture to initiate polymerization. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 2 h after which nanoparticles were precipitated and washed 4 times with excess ethanol to remove unreacted monomer, template and surfactant. Nanoparticles were collected, resuspended in water and purified by gel chromatography (G50). Purified nanoparticles were lyophilized and kept at room temperature until further characterization. NQA imprinted nanoparticles (NQA-MINs) and non-imprinted nanoparticles (NINs) were prepared in the same way using NQA as template in the former and no template in the latter.

2.4. Particle size and morphology

Size and zeta potential of nanoparticles were measured using a Malvern Zetasizer® Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, UK). Nanoparticles were suspended in deionized water at a concentration of 2 mg/mL and sonicated prior to measurement. Nanoparticle morphology was examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEM-2100 F, JEOL, Japan) and dynamic light scattering (DLS).

2.5. Template nanoparticle interaction

2.5.1. SPR analysis

Template-nanoparticle interaction was investigated using a Biacore X100 instrument (GE Healthcare, USA). NQA was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip according to the manufacturer׳s instructions. Suspensions of nanoparticles were filtered through 0.22 μm syringe filters and diluted in HBS-EP buffer (GE Healthcare, USA) to give a three-fold concentration series (0.25, 0.74, 2.22, 6.67 and 20 mg/mL). The freshly prepared suspensions were then allowed to flow over the NQA sensor chip according to a so-called “kinetic titration” procedure using HBS-EP as running buffer13, 14. For each injection, nanoparticle suspensions flowed over the sensor chip at 20 μL/min at 25 °C for 3 min. An unmodified sensor chip served as a reference to correct for instrumental noise and drift.

2.5.2. Change in zeta potential

Analysis of zeta potential was based on the “mucin particle method” previously used to study the mucoadhesion of polymers to commercially available mucin particles15. Briefly, to nanoparticle suspensions in water (4 mg/mL), NQA was added to give a final concentration of 75 μg/mL and incubated overnight. Since NQA is positively charged at pH 7.0 (pI 9.5), it was assumed that the zeta potential of nanoparticles would increase due to adsorption of template. Zeta potential of nanoparticles was monitored using a Malvern Zetasizer® Nano Series DTS 1060 (Malvern Instruments, UK).

2.5.3. Fluorescence polarization (FP) studies

The application of FP is based on the assumption that binding of the fluorescence-labeled molecule to nanoparticles decreases its molecular rotation in solution which can be detected by FP. NQA was N-terminally labeled with FAM and purified. Then a constant amount of FAM-labeled peptide (about 20 nmol/L) was incubated with suspensions of nanoparticles in water at a range of concentrations. FP was measured using a Tecan M1000 microplate reader (Tecan, Swiss), and values corrected by subtracting the value corresponding to the labeled peptide in water.

2.6. In vitro interaction between nanoparticles and H. pylori

2.6.1. Flow cytometry studies

A BD FACSCalibur fluorescence-activated flow cytometer (BD, USA) was used to investigate the interaction between nanoparticles and H. pylori. FAM-loaded nanoparticles (FAM-Myr-NQA-MINs, FAM-NQA-MINs and FAM-NINs) were prepared by adding FAM during their preparation. FAM-loaded nanoparticles were separated from free FAM by gel chromatography and lyophilized. Examination by fluorescence spectrometry showed that all nanoparticles displayed similar fluorescence intensity. The standard microbial strain of H. pylori (Sydney Strain SS1) was cultivated for two days microaerophilically at 37 °C on solid medium. The bacteria were then suspended in physiological saline and nutrient medium, respectively, incubated with 2 mg/mL FAM-loaded nanoparticles for 2 h and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Finally samples were centrifuged, rinsed and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. For each measurement, 1×104 and 2×104 bacteria were counted to determine the number giving a positive signal in the FL-1 channel.

2.6.2. Studies using the SS1-AGS model

A fluorescence microscope was used to observe the in vitro interaction between nanoparticles and SS1 H. pylori adsorbed on AGS cells. This was based on the premise that the SS1-AGS model mimics the adhesion of H. pylori to gastric epithelial cells in vivo. SS1 bacteria were microaerophilically cultivated for 48 h at 37 °C on solid medium and then suspended in F12 medium at about 1.0×108 cells/mL. AGS cells were cultivated in a 24-well plate for 48 h after which 0.3 mL bacteria suspension was added into each well and incubated for 1 h before washing 3 times with saline. Then aliquots (0.3 mL) of suspensions (2 mg/mL) of FAM-loaded nanoparticles were added into each well and incubated with either AGS cells or the SS1-AGS model for 2 h. Finally samples were examined by fluorescence microscopy.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical comparison between samples was evaluated by Student's t-tests performed using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis of SMINs

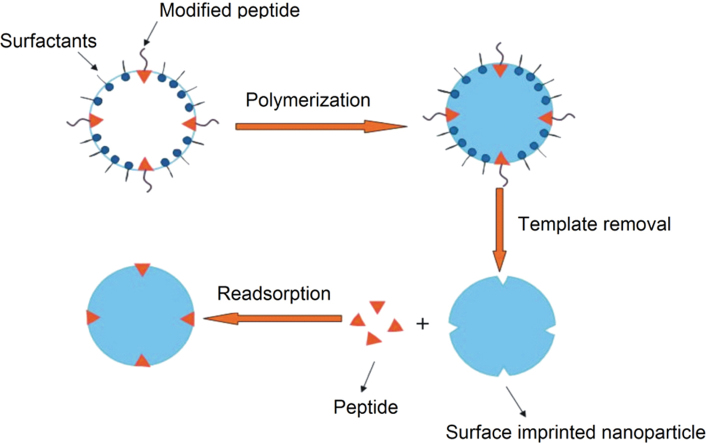

Subsequent to the conventional bulk polymerization method in which template molecules are embedded within the bulk of the polymer matrix, some novel approaches such as mini-emulsion polymerization and precipitation polymerization have recently been introduced to prepare micro- and nano-structured protein imprinted polymers16, 17, 18. Compared to the conventional approach, the products of these newer techniques possess higher adsorption capacity due to their increased surface area. However, they are still deficient, because protein molecules are mostly hydrophilic and randomly distributed in the aqueous monomer solution, the majority of protein is restricted in the polymeric matrix and inaccessible to the template. To solve this problem, we employed inverse microemulsion polymerization as proposed by Zeng et al.5 and modified the hydrophilic NQA with the long-chain fatty acid, myristic acid, to form an amphiphilic molecule. During the emulsion process, the amphiphilic template functions as a surfactant and arranges itself at the oil-water interface with its hydrophilic head protruding into the aqueous phase and its hydrophobic tail oriented outwards. This was anticipated to promote interaction between the hydrophilic peptide and the monomer and also create imprints directly at or near the surface of the nanoparticles. The template should then have easy access to surface specific sites as found in the natural immune response where only the surface epitope part of a macromolecule is recognized by the antibody2. The preparation procedure is summarized in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the preparation of surface molecularly imprinted nanoparticles.

3.2. Particle size and morphology

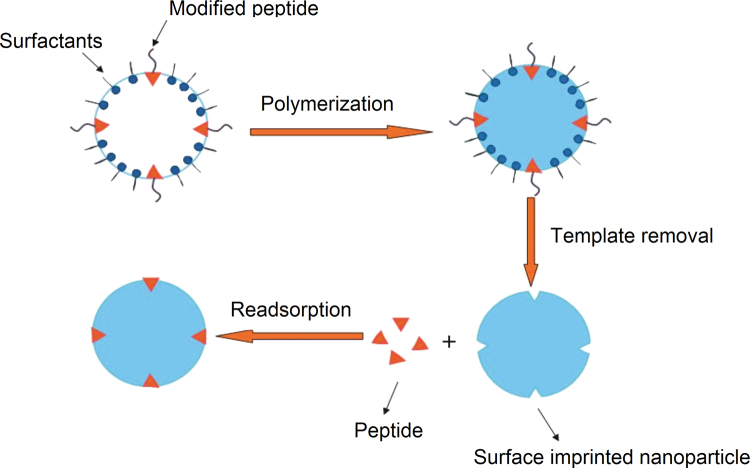

A TEM micrograph showing the morphology of Myr-NQA-MINs is shown in Fig. 1. The nanoparticles are seen to be regularly shaped and highly monodispersed. DLS studies (Table 1) show that nanoparticles were about 30 nm in diameter and display similar values of particle distribution index (PDI) despite the addition of template peptide during preparation.

Figure 1.

Micrograph of Myr-NQA-MINs obtained by transmission electron microscopy. The scale bars represents 100 nm.

Table 1.

Summary information of the sizes of NINs, NQA-MINs and Myr-NQA-MINs.

| Sample | Mean diameter (nm) | PDI |

| NINs | 30.4 | 0.126 |

| NQA-MINs | 28.5 | 0.155 |

| Myr-NQA-MINs | 27.9 | 0.200 |

NINs, non-imprinted nanoparticles; NQA-MINs, NQA imprinted nanoparticles; Myr-NQA-MINs, myristic acid modified NQA imprinted nanoparticles; PDI, particle distribution index.

3.3. SPR studies

Interaction between immobilized NQA and nanoparticles as studied by SPR is shown in Fig. 2. It was found that injection of Myr-NQA-MINs resulted in a marked concentration-dependent increase in response values (RU). Thus injection of suspensions with the three higher concentrations (2.22, 6.67 and 20 mg/mL) led to particularly high levels of RU whereas signals for nanoparticle suspensions with lower concentrations were less significant. This indicates that, at higher concentrations, the presence of a large number of high-affinity binding sites on the surface of Myr-NQA-MINs offers more opportunity for rapid adsorption of template molecules. NQA-MINs did not seem to interact strongly with immobilized template at any concentration and its sensorgram was quite similar to that of NINs. This was probably because the absence of surface imprints prevented them from effectively interacting with the template molecules. These results indicate the successful fabrication of specifically imprinted cavities on the surface of Myr-NQA-MINs.

Figure 2.

Sensorgrams of time-dependent binding of Myr-NQA-MINs, NQA-MINs and NINs to template peptide immobilized on an SPR chip. The corresponding concentrations of nanoparticles are 0, 0.25, 0.74, 2.22, 6.67 and 20 mg/mL.

Interestingly, no dissociation of bound nanoparticles was observed at any concentration after the association process. This is consistent with the findings of Verheyen et al.12 who concluded that the absence of dissociation was due to a very strong interaction between SMINs and template. However, we maintain that, besides the interaction, the phenomenon could also be partly due to sedimentation of nanoparticles onto the sensor chip leading to a “strong binding” artifact. Because of this, we employed a “kinetic titration” approach characterized by sequentially injecting an increasing concentration of nanoparticles with no regeneration step13, 14.

3.4. Change in zeta potential

According to the “mucin particle method”, the surface of mucin particles is changed by adhesion of mucoadhesive polymer giving rise to a change in zeta potential of the particles15. Changes resulting from the interaction between templates and nanoparticles are shown in Fig. 3. For NINs, NQA-MINs and Myr-NQA-MINs, zeta potential increased by 2.86, 2.88 and 5.22 mV respectively. This was as expected given that surface imprinted Myr-NQA-MINs probably display a higher affinity toward NQA than its counterparts. For NINs and NQA-MINs, the increase in zeta potential is probably due to nonspecific adsorption of template peptide.

Figure 3.

(a) Zeta potential of NINs, NQA-MINs and Myr-NQA-MINs before (white) and after (black) incubation with NQA for 12 h and (b) the zeta potential differences (*P<0.01, Student's t-test).

3.5. FP studies

FP is a versatile solution-based technique that has long been employed to study protein–protein interactions. The principle of FP derives from the fact that the degree of polarization of a fluorophore (in this case FAM) is inversely related to its molecular rotation as indicated in Scheme 219. As shown in Fig. 4, at low concentrations of nanoparticles (0.78 and 1.56 μg/mL), FP of Myr-NQA-MINs after incubation with FAM labeled template was significantly higher than FP of NQA-MINs and NINs. This can be attributed to the higher affinity of Myr-NQA-MINs for template molecules. However, at higher concentrations of nanoparticles (100 and 200 μg/mL), there were no significant differences in FP of the three types of nanoparticles. This is presumably because in all cases the majority of template molecules are adsorbed onto the nanoparticles due to both specific and nonspecific interactions and the greater affinity of Myr-NQA-MINs for template is masked.

Scheme 2.

Illustration of the principle of fluorescence polarization as applied to study the interaction between template and nanoparticles.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence polarization of FAM-labeled NQA (20 nmol/L) after incubation with nanoparticles suspensions with different concentrations (*P<0.01, **P<0.005, Student's t-test). NPs, nanoparticles.

3.6. H. pylori adhesion studies

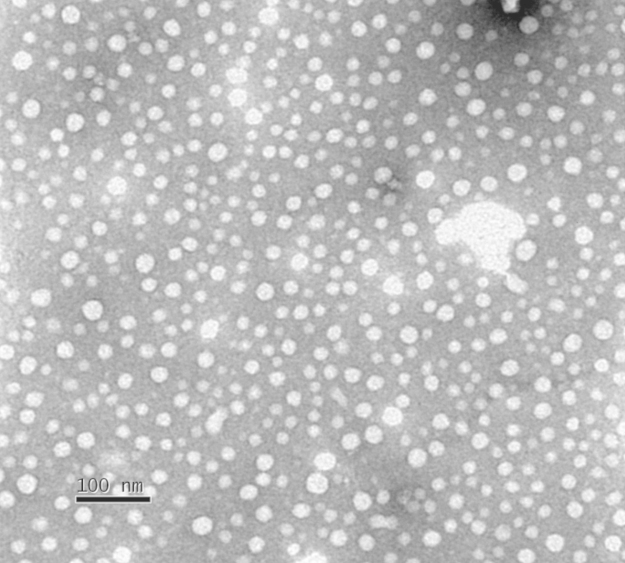

3.6.1. Cytometric analysis

The ability of the three types of nanoparticles to adhere to H. pylori is compared in Fig. 5. Binding of NINs to H. pylori still occurred presumably due to non-specific adsorption. Adsorption of Myr-NQA-MINs was the highest but adsorption of NQA-MINs was somewhat inconsistent being higher than that of NINs for some groups but less for others. We hypothesize this reflects inconsistent imprinting of the surface of NQA-MINs due to the hydrophilic quality of NQA or that the sites created do not matchthe NQA on the SS1 H. pylori bacteria.

Figure 5.

Specific binding of various nanoparticles to the Sydney Strain of H. pylori (SS1) detected by flow cytometry (*P<0.01, Student's t-test).

3.6.2. Fluorescence microscopy studies

Both FAM-Myr-NQA-MINs and FAM-NINs were adsorbed onto AGS cells but the surface fluorescence intensity on AGS cells was much lower than that on the SS1-AGS model (Fig. 6). FAM-Myr-NQA-MINs were adsorbed more on H. pylori as indicated by the higher fluorescence intensity on the bacteria. On the other hand, FAM-NINs were scattered more randomly on the surface of the AGS cells. We infer this is because Myr-NQA-MINs are recognized by the surface lipoprotein of H. pylori and are more specifically absorbed while NINs are probably adsorbed non-specifically onto AGS cells.

Figure 6.

Representative fluorescent photomicrographs of binding of various nanoparticles to SS1-AGS model. The concentration of nanoparticles is 2 mg/mL. The scale bars represents 200 μm.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, we prepared a novel peptide imprinted nanoparticle for specific H. pylori adhesion. We used the general strategy of surface imprinting with an epitope imprinting approach. Studies of the interaction between template peptide and nanoparticles based on SPR, change in zeta potential and FP indicated that Myr-NQA-MINs possess specific recognition sites for the template compared to NQA-MINs and NINs. A preliminary in vitro study of the ability of these surface molecularly imprinted nanoparticles to adhere to H. pylori was sufficiently positive to encourage us to further explore the therapeutic potential of this kind of nanoparticle for H. pylori eradication.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 30973653, H3008/81102385) and National S&T Major Special Project on Major New Drug Innovation (No. 2009ZX09310-006).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Andrews G.P., Laverty T.P., Jones D.S. Mucoadhesive polymeric platforms for controlled drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;71:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ge Y., Turner A. Too large to fit? Recent developments in macromolecular imprinting. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitcombe M.J., Chianella I., Larcombe L., Piletsky S.A., Noble J., Porter R. The rational development of molecularly imprinted polymer-based sensors for protein detection. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1547–1571. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00049c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kryscio D.R., Peppas N.A. Critical review and perspective of macromolecularly imprinted polymers. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng Z.Y., Hoshino Y., Rodriguez A., Yoo H.S., Shea K.J. Synthetic polymer nanoparticles with antibody-like affinity for a hydrophilic peptide. ACS Nano. 2010;4:199–204. doi: 10.1021/nn901256s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostrzynska M., Otoole P.W., Taylor D.E., Trust T.J. Molecular characterization of a conserved 20-kilodalton membrane-associated lipoprotein antigen of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5938–5948. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.5938-5948.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keenan J., Oliaro J., Domigan N., Potter H., Aitken G., Allardyce R. Immune response to an 18-kilodalton outer membrane antigen identifies lipoprotein 20 as a Helicobacter pylori vaccine candidate. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3337–3343. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3337-3343.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y.J., Liu Y., Xie C., Lu W.Y., Pan J. Preparation and evaluation of lysozyme molecularly imprinted microspheres. Chin J Pharm. 2011;42:747–751. 765. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishino H., Huang C.S., Shea K.J. Selective protein capture by epitope imprinting. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:2392–2396. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xue X.H., Pan J., Xie H., Wang J.H., Zhang S.A. Specific recognition of Staphylococcus aureus by Staphylococcus aureus protein A-imprinted polymers. React Funct Polym. 2009;69:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan J., Xue X.H., Wang J.H., Me H.M., Wu Z.Y. Recognition property and preparation of Staphylococcus aureus protein A-imprinted polyacrylamide polymers by inverse-phase suspension and bulk polymerization. Polymer. 2009;50:2365–2372. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verheyen E., Schillemans J.P., van Wijk M., Demeniex M.A., Hennink W.E., van Nostrum C.F. Challenges for the effective molecular imprinting of proteins. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3008–3020. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson R., Katsamba P.S., Nordin H., Pol E., Myszka D.G. Analyzing a kinetic titration series using affinity biosensors. Anal Biochem. 2006;349:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thillaivinayagalingam P., Gommeaux J., McLoughlin M., Collins D., Newcombe A.R. Biopharmaceutical production: applications of surface plasmon resonance biosensors. J Chromatogr B. 2010;878:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeuchi H., Thongborisute J., Matsui Y., Sugihara H., Yamamoto H., Kawashima Y. Novel mucoadhesion tests for polymers and polymer-coated particles to design optimal mucoadhesive drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:1583–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan C.J., Tong Y.W. The effect of protein structural conformation on nanoparticle molecular imprinting of ribonuclease A using miniemulsion polymerization. Langmuir. 2007;23:2722–2730. doi: 10.1021/la062178q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan C.J., Wangrangsimakul S., Bai R., Tong Y.W. Defining the interactions between proteins and surfactants for nanoparticle surface imprinting through miniemulsion polymerization. Chem Mater. 2008;20:118–127. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoshino Y., Kodama T., Okahata Y., Shea K.J. Peptide imprinted polymer nanoparticles: a plastic antibody. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15242. doi: 10.1021/ja8062875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lea W.A., Simeonov A. Fluorescence polarization assays in small molecule screening. Exp Opin Drug Discov. 2011;6:17–32. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.537322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]