Abstract

The sweet taste receptor, a heterodimeric G protein-coupled receptor comprised of T1R2 and T1R3, binds sugars, small molecule sweeteners, and sweet proteins to multiple binding sites. The dipeptide sweetener, aspartame binds in the Venus Flytrap Module (VFTM) of T1R2. We developed homology models of the open and closed forms of human T1R2 and human T1R3 VFTMs and their dimers and then docked aspartame into the closed form of T1R2’s VFTM. To test and refine the predictions of our model, we mutated various T1R2 VFTM residues, assayed activity of the mutants and identified 11 critical residues (S40, Y103, D142, S144, S165, S168, Y215, D278, E302, D307, and R383) in and proximal to the binding pocket of the sweet taste receptor that are important for ligand recognition and activity of aspartame. Furthermore, we propose that binding is dependent on 2 water molecules situated in the ligand pocket that bridge 2 carbonyl groups of aspartame to residues D142 and L279. These results shed light on the activation mechanism and how signal transmission arising from the extracellular domain of the T1R2 monomer of the sweet receptor leads to the perception of sweet taste.

Key words: aspartame, cyclamate, homology modeling, site-directed mutagenesis, sweet taste receptor

Introduction

Humans and other mammals can detect and discriminate between at least 5 taste qualities: sweet, bitter, sour, salty, and umami (Lindemann 1996). Identification of sweet tasting compounds is important from an evolutionary perspective in selecting essential carbohydrates with high nutritive and caloric value (Nelson et al. 2001; Margolskee 2002; Amrein and Bray 2003, ). Recent debate has centered on if over-consumption of low-complexity sugars may have an addictive component due to the consistent release of dopamine, and is therefore contributing to the obesity epidemic facing much of the world (Avena et al. 2008). Research to better understand the basic mechanisms underlying taste transduction in mammals can help address these questions. Despite identification of the taste receptor type 1 subtypes 2 and 3 (T1R2, T1R3) in heteromeric and possibly in homomeric forms as underlying the detection of all sweet taste stimuli (Kitagawa et al. 2001; Max et al. 2001; Montmayeur et al. 2001; Li et al. 2002; Xu et al. 2004), the molecular details of the sweet taste receptor are still unclear.

The heterodimer of T1R2 and T1R3 (T1R2 + T1R3) is recognized as the predominant sweet taste receptor. It is responsive to natural sugars, as well as artificial sweeteners, d-amino acids, and sweet-tasting proteins (Montmayeur et al. 2001; Nelson et al. 2001; Li et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2004). The T1Rs are family C G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and are related to metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), calcium sensing receptors, and a subset of vomeronasal receptors (Pin et al. 2003). T1Rs are characterized by a large extracellular amino terminal domain, which resembles the Venus Flytrap Module (VFTM) in other family C GPCRs (Pin et al. 2003). The VFTM is linked by a cysteine rich domain (CRD) to the 7-helix transmembrane domain (TMD) (Pin et al. 2003).

Previous studies indicated that aspartame may bind in the same cleft in the VFTM of T1R2 as do sugars (Xu et al. 2004; Cui et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2011; Masuda et al. 2012). Other mapping studies specify that the artificial sweetener cyclamate binds in the TMD of T1R3 (Xu et al. 2004; Jiang et al. 2005c), whereas sweet proteins, such as brazzein, bind to the CRD of T1R3 in conjunction with the VFTM of T1R2 (Jiang et al. 2004; Assadi-Porter et al. 2010). Others have identified yet another binding site in the TMD of T1R2 (Slack 2009). Thus, 5 and possibly more distinct binding domains, each containing multiple overlapping binding sites, have been identified in the heteromeric receptor. In contrast, receptor activation by all known sweeteners is inhibited by lactisole (Sclafani and Perez 1997; Schiffman et al. 1999), which binds in the TMD of T1R3, and perhaps overlaps cyclamate’s binding site (Jiang et al. 2005b; Winnig et al. 2005). Interestingly, under certain conditions cyclamate does indeed act on the umami receptor. Cyclamate by itself did not activate the T1R1 + T1R3 receptor, but cyclamate potentiated the T1R1 + T1R3 receptor’s response to l-glutamate (Xu et al. 2004).

The sweet taste receptor’s mode of activation may be similar to that of mGluR’s (Kunishima et al. 2000; Tsuchiya et al. 2002; Jingami et al. 2003; Jiang et al. 2005a; Muto et al. 2007). The ligand free and bound crystal structures of mGluR show that the binding site for glutamate is located between the 2 distinct lobes of the VFTM, which are linked by a hinge region (3 beta strands that are discontinuous in the primary sequence). The binding of glutamate in the cleft between the lobes stabilizes a closed conformation, which upon rotation around the lobe 1 dimer interface converts the resting state of mGluR to the active form. A disulfide bond between a conserved cysteine at the bottom of lobe 2 of the VFTM and the third of 9 conserved cysteines in the CRD has been shown to be critical for transmission of the VFTM/CRD active structure to the TMD (Kunishima et al. 2000; Jingami et al. 2003). Assuming this mechanism is general to all family C receptors, binding of a sweetener within the VFTM would induce or stabilize closing of the 2 lobes, which in turn would lead to a reorientation of the 2 protomers in the heterodimer and ultimately to full or partial receptor activation.

In this report, we focus on the binding of the artificial sweetener aspartame in the orthosteric binding pocket in the VFTM of human T1R2 (hT1R2). Aspartame (l-aspartyl-l-phenylalanine methyl ester), discovered in 1965 by James Schlatter, is approximately 180 times sweeter than sucrose (Mazur et al. 1969; Meguro et al. 2000). We have used homology modeling and in silico docking strategies to computationally identify the sweet receptor binding site for aspartame, proposed to lie in the VFTM cleft. Using the refined docked model, we made directed mutations of residues predicted to be in contact with aspartame and then tested the resulting receptors for their activity. We included cyclamate as a global control for specific effects of mutation on the aspartame binding site. Our experimental results agree well with the predictions of the docked models. In turn, the refined docked models provide a detailed picture of the structural details of activation by aspartame.

Materials and methods

Materials

Cyclamate was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. Aspartame and SC45647 were gifts from the Coca-Cola Company. Fetal bovine serum, Fluo-4 AM cell permeant, Gibco HBSS buffer, Gibco 1M HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) buffer, Lipofectamine2000, Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium, and GlutaMAX Supplement culture medium were obtained from Life Technologies. 96-well poly-D-lysine plates were purchased from Corning. All solutions were made on the day of the experiment.

Homology modeling and model refinement

Homology models of hT1R2 + hT1R3 VFTMs (open/closed and closed-open/A forms) (Kunishima et al. 2000) have been constructed with the MODELLER program (Sali and Blundell 1993; Marti-Renom et al. 2000) using the mGluR1-VFTM crystal structure (PDB entry: 1EWK) (Kunishima et al. 2000) as the template. In the crystal structure of the mGluR1 VFTMs, the loop between residues R124 and K154 is missing in both protomers of the crystal. We generated these loop regions for our model with the MODELLER program and constrained the structure with disulfide bonds selected from the corresponding residues within mGluR1’s structure: C67-C109, C378-C394, and C432-C439 (Sali and Blundell 1993; Marti-Renom et al. 2000). A multiple sequence alignment of the VFTMs of hT1R2, hT1R3, mouse T1R2 (mT1R2), mouse T1R3 (mT1R3), and mGluR1 was generated using ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994), followed by minor manual adjustments in the highly variable regions. The models of the VFTMs were refined with the CHARMM program (Brooks et al. 1983); the model was surrounded with a 6Å water shell and minimized for 5000 steps of steepest descent (SD) with the VFTM fixed. This was followed by 5000 steps of SD minimization with the backbone of the VFTM fixed, 5000 steps of SD minimization without restraints, and 40000 steps of Adapted Basis Newton-Raphson (ABNR) minimization or until the root mean square energy gradient of 0.05 kcal/mol/Å had been achieved.

Molecular docking

The geometries of aspartame were optimized by ab initio quantum chemistry at the HF/6- 31G* level, followed by single point calculations with the polarized continuum model (PCM) to obtain the molecular electrostatic potential for charge fitting. The CHELPG charge-fitting scheme was used to calculate partial charges on the atoms (Breneman and Wiberg 1990). The ab initio calculations were carried out with the GAUSSIAN 98 program (Frisch et al. 2001).

An automatic molecular docking program, AUTODOCK (Morris et al. 1998) was used for the docking studies. A grid map was generated for the hT1R2 VFTM using CHNO elements sampled on a uniform grid containing 86×76×74 points, 0.375Å apart. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) was selected to identify the binding conformations of the ligands. Hundred docking simulations were performed for each of the ligands. The final docking was selected based on binding energies and cluster analysis (the lowest energy conformation was also the largest cluster). The complexes were then refined using the same protocol as described previously.

Preparation of chimeras and point mutants

Human and mouse T1R2 and T1R3 clones were as described (Jiang et al. 2004). The Gα16-gus44 chimeric G-protein α-subunit contains 44 α-gustducin-homologous amino-acids at the C-terminus of Gα16 (as described in Ueda et al. 2003). A human-mouse chimeric receptor (amino acids 1–468 from hT1R2 and the remainder from mouse) was constructed using an overlapping PCR strategy as described (Jiang et al. 2004). Point mutations in the VFTM of human T1R2 were made by the same overlapping PCR strategy or by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). The integrity of all DNA constructs was confirmed by sequencing. Expression of the chimeric and mutant protein in HEK293 EBNA (HEK293E) cells was confirmed by immunostaining against the flag epitope tag inserted at the C-terminus of the T1R2 construct.

Heterologous expression

HEK293E cells were cultured at 37 °C in Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium supplemented with 4% dialyzed fetal bovine serum. Cells were transfected using lipofectamine2000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (InvitrogenTM). Cells were seeded onto 96-well poly-d-lysine plates at ~12500 cells/well 18h prior to transfection; cells in each well were cotransfected with plasmid DNAs encoding T1Rs and Gα16-gus44 (0.1 μg total DNA/well; 0.2 μL lipofectamine2000/well). After 24h, the transfected cells were washed once with culture medium. After an additional 24h, the cells were washed once with HBSS supplemented with 20mM HEPES, loaded with 75 μL of 3 μM Fluo-4 AM (molecular probe) diluted in HBSS-HEPES buffer, incubated for 1.5h at room temperature, and then washed twice with HBSS-HEPES and maintained in 50 μL HBSS-HEPES at 25 °C. The plates of dye-loaded transfected cells were placed into a FlexStation II system (Molecular Devices, LLC) to monitor fluorescence (excitation, 488nm; emission, 525nm; cutoff, 515nm). Tastants were added 30 s after the start of the scan at 2× concentration in 50 μL of HBSS-HEPES while monitoring fluorescence for an additional 200 s at 2 s intervals.

Data analysis

After obtaining a calcium mobilization trace for each sample, calcium responses to tastants were quantified as the percentage of change (peak fluorescence − baseline fluorescence level, denoted as ΔF) from baseline fluorescence level (denoted as F); ΔF/F (%). Peak fluorescence intensity occurs about 20–30 s after the addition of tastants. Typically, the wild type sweet receptor heterodimer plus Gα16-gus44 evoked a calcium response accounting for a ΔF/F signal arising from 40% to 100%. As controls, buffer alone and tastant responses on nonfunctional mutants or T1R3 alone plus Gα16-gus44 evoked no significant change of fluorescence (−5% ≤ ΔF/F ≤ 5%, SE is about 2%). The data were expressed as the mean ± SE of quadruplicate experiments. The bar graph and curving-fitting routines were carried out using Graph-Pad Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

The measurement of the differences in log(EC50) values (Δlog(EC50)) of the mutants compared with WT in response to the sweeteners aspartame and cyclamate were calculated. Independent experiments were performed at least 4 times. Due to insolubility properties, or toxicity/artifact/osmolarity issues, some sweeteners could not be used in high enough concentrations to reach response saturation (Aspartame ≥ 20mM; cyclamate ≥ 100mM). Values from different experiments were normalized from 0 (buffer alone) to 100 (saturation of the response; Emax) and sigmoid curves were fit to the data set to calculate apparent EC50 values ± SE. The changes in log (EC50) from wildtype were plotted. Where Emax could not be obtained, we plotted the change in log (EC50) as “greater than” the minimal value estimated for saturation.

Results

The VFTM of T1R2 determines responsiveness to aspartame

The sweet receptor T1R2 + T1R3 is predicted to share similarities with other heterodimeric class C GPCRs whose subunits have asymmetrical functions (Goudet et al. 2005). Consistent with such a mechanism, the umami receptor (T1R1 + T1R3), despite containing the T1R3 subunit shared by the sweet taste receptor, does not respond to aspartame or other sweeteners. In another instance, cyclamate, whose binding site is located on the TMD of T1R3 has been shown to be an agonist of the sweet T1R2 + T1R3 receptor but was a positive allosteric modulator (PAM) of the umami T1R1 + T1R3 receptor whereas aspartame was not (Xu et al. 2004). Furthermore, it was shown that a T1R2 chimera containing the extracellular portion of human T1R2 (VFTM and CRD) was sufficient to provide sensitivity to aspartame to the otherwise aspartame-insensitive rat T1R2 + T1R3 receptor (Xu et al. 2004). The same authors showed that single point mutations in the VFTM of T1R2 (S144 and E302A) abolished sensitivity to aspartame, suggesting that aspartame binds in the mouth of the VFTM. In addition, the experiments of Liu et al. (2011) showed that the combination of squirrel monkey T1R2 and human T1R3 is functional but not responsive to aspartame (Liu et al. 2011). Consequently, the binding site of aspartame and other prototypical sweeteners has been localized to the T1R2 subunit. To more narrowly map the molecular interactions of aspartame with the taste receptor, we used the known differential divergent sensitivity to dipeptide sweeteners displayed by mouse and human sweet receptors (Bachmanov et al. 2001, Sclafani and Abrams 1986, Wagner 1971). We constructed a series of chimeric sweet taste receptors by mixing domains from mouse and human T1R2 and T1R3. We then heterologously expressed and tested the resulting mixed species sweet receptors for sensitivity to a panel of sweeteners using a calcium mobilization assay.

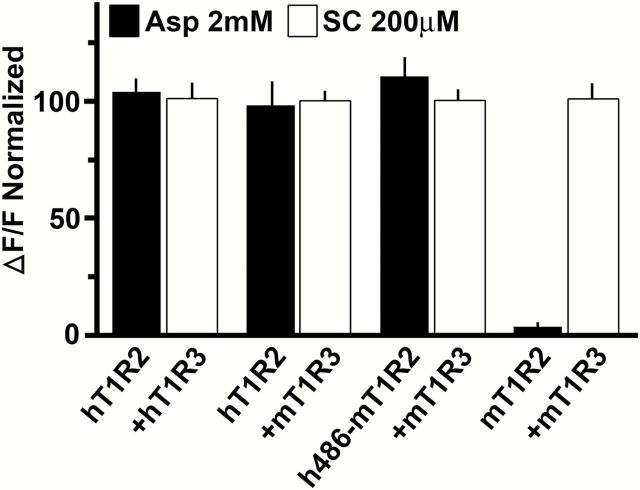

SC45647, a guanidine sweetener which tastes sweet to both humans and rodents (Bachmanov et al. 2001; Heyer et al. 2004), was used as a positive control. SC45647 activated all combinations of mixed species and chimeric receptors in our assays. As expected, the fully human sweet receptor was sensitive to both sweeteners but the mouse pair was responsive to only SC45647, showing no response to aspartame. When hT1R2 was paired with mT1R3, the mixed species receptor was again able to respond to both sweeteners in approximately equal intensity to the fully human receptor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sweet receptor responsiveness to aspartame depends upon the VFTM of T1R2. Human (hT1R2 + hT1R3), mouse (mT1R2 + mT1R3), human + mouse (mixed species) (hT1R2 + mT1R3), and human/mouse chimera (where the first 468 amino acids of the VFTM of human T1R2 replaces that of the corresponding mouse sequence h468mT1R2 + mT1R3) sweet-sensing receptors were expressed in HEK293E cells, along with Gα16-gus44. Calcium (Ca2+) mobilization in response to sweeteners was measured with a fluorescent Ca2+ dye. The response is calculated from the ratio of the fluorescence at the peak of the response following addition of tastant over baseline fluorescence (ΔF/F) and normalized to the SC45647 response (see Materials and methods for details). Values are mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments. Sweetener concentrations are: aspartame (Asp) (2mM) and SC45647 (SC) (200 μM). Both sweeteners activated hT1R2 + hT1R3, hT1R2 + mT1R3, and h468mT1R2 + mT1R3. Only SC45647 activated mT1R2 + mT1R3. The hT1R3/mT1R3 combination was unresponsive to all sweeteners as previously described (Jiang et al. 2005a).

To confirm that the VFTM of hT1R2 is the domain of interaction, we examined a heterodimer of chimeric human/mouse T1R2, composed of the first 468 amino acids of hT1R2 (comprising the majority of the VFTM) with the remainder from mT1R2 (h468-mT1R2), paired with the mT1R3 protomer. The chimeric human/mouse receptor was responsive to both sweeteners (Figure 1).

Model structures of the VFTMs of hT1R2 and hT1R3

To identify potential binding sites for the dipeptide sweetener aspartame, we first constructed a homology model of the hT1R2 + hT1R3 VFTM heterodimer. The multiple sequence alignments of the VFTMs of hT1R2, hT1R3, mT1R2, mT1R3, and mGluR1 are shown in Supplementary Figure 1A. The refined model of hT1R2 and hT1R3 VFTMs (based on the closed and open forms of mGluR1 VFTMs, respectively) was evaluated by the Verify3D program; the 3D profile score of the model is shown in Supplementary Figure 1B with acceptable values (Bowie et al. 1991; Luthy et al. 1992). The refined hT1R2 + hT1R3 VFTM model is shown in Figure 2A.

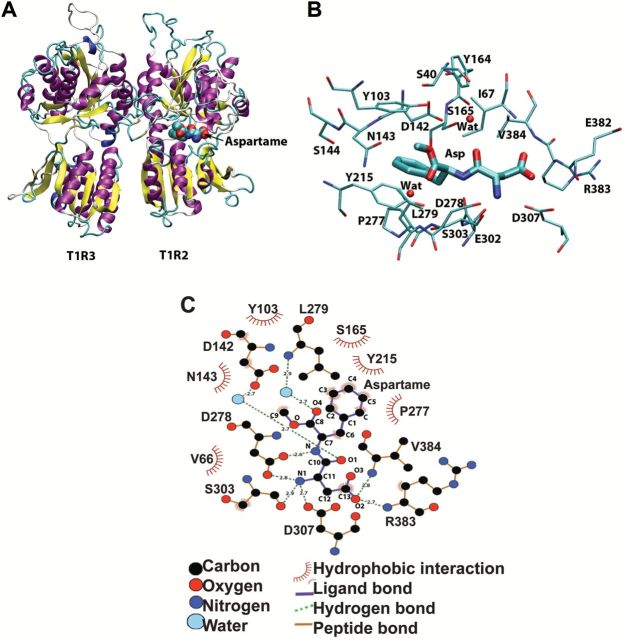

Figure 2.

Models of the sweet receptor VFTM. (A) A cartoon representation of the homology model of hT1R2+3 (VFTM only). (B) The refined docked complex structure of hT1R2 (VFTM) binding to aspartame. Only the binding pocket of hT1R2 VFTM is shown. Two water molecules (Wat) within the binding pocket are shown. (C) A schematic representation generated by LIGPLOT of the main interactions between the hT1R2 binding site of aspartame.

Aspartame docks to the closed form of the hT1R2 homology model

To discover the mode of binding of aspartame to the sweet taste receptor, we docked aspartame into the cleft of the hT1R2 VFTM model (Goodsell et al. 1996; Morris et al. 1998). About 36% of the configurations for aspartame were included in the first cluster with scores that are related to good binding free energies. The configurations with lowest values for aspartame (−9.6 kcal/mol) were selected for refinement of the complexes. A representative of the final refined structures of aspartame bound in the ligand-binding pocket of the hT1R2 VFTM is shown in Figure 2B. The neutral and positively charged amine groups of the sweetener point to negatively charged residues of the receptor as D307, S303, and D278, whereas the phenyl and methyl groups of the ligand are in hydrophobic regions of the receptor toward S165, Y215, and P277. Interestingly, 2 water molecules, which may be important for ligand binding, provide a link between the ligand and 2 carbonyl groups in the binding pocket. To visualize these interactions in detail, we generated 2-dimensional interaction schematics using the LIGPLOT program (McDonald and Thornton 1994; Wallace et al. 1995) and the schematics are shown in Figure 2C. The hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions between aspartame and the receptor identified by LIGPLOT program are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Hydrogen-bonds between hT1R2 (VFTM) and aspartame

| hT1R2 | VFTM | Aspartame | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | Atom | Atom | Distance (Å) |

| D278 | OD2 | N | 2.65 |

| D278 | OD1 | N1 | 2.80 |

| S303 | O | N1 | 2.89 |

| D307 | OD1 | N1 | 2.68 |

| R383 | N | O2 | 2.71 |

| V384 | N | O2 | 2.82 |

| H2O-a | O | O1 | 2.69 |

| D142 | OD2 | H2O-a-O | 2.70 |

| H2O-b | O | O4 | 2.71 |

| L279 | N | H2O-b-O | 2.96 |

Table 2.

Hydrophobic interactions between hT1R2 (VFTM) and aspartame

| hT1R2 | VFTM | Aspartame | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | Atom | Atom | Atom |

| V64 | CB | ||

| V64 | CB | ||

| V64 | CG1 | ||

| V64 | CG2 | ||

| V66 | CG1 | C13 | 3.87 |

| V66 | CG2 | ||

| I67 | CD | ||

| I67 | CG1 | ||

| Y103 | CZ | C9 | 3.38 |

| Y103 | CE2 | C9 | 3.69 |

| D142 | CB | C3 | 3.76 |

| N143 | CG | C3 | 3.74 |

| S165 | CB | C5 | 3.52 |

| Y215 | CZ | C4 | 3.86 |

| Y215 | CE1 | C4 | 3.77 |

| Y215 | CD1 | C5 | 3.82 |

| P277 | CG | C3 | 3.89 |

| P277 | CB | C2 | 3.68 |

| D278 | CG | ||

| S303 | CB | C6 | 3.89 |

| L310 | CD1 | ||

| R383 | CB | C13 | 3.77 |

Identifying the residues within hT1R2’s VFTM that interact with aspartame

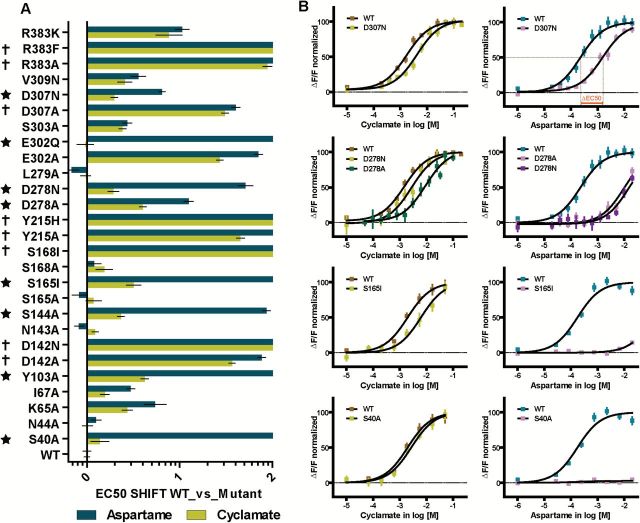

To test the predictions of the refined docked models, we mutated to alanine those residues predicted to have interactions with aspartame and assayed the resulting mutant receptors in a calcium mobilization assay comparing activation by aspartame to that of cyclamate (a positive control for global responsiveness of mutant receptors) (Xu et al., 2004; Jiang et al. 2005c). Plotting Δlog (EC50) values of different mutant receptors for multiple sweeteners (Figure 3) is useful to quantitatively compare shifts in potency for different sweeteners elicited by particular mutations. Note that a mutant displaying a similar degree of loss of function or loss of potency for 2 compounds known to bind to different receptor sites (e.g., aspartame in the VFTM of T1R2 and cyclamate in the transmembrane segment of T1R3) would not be marked as “specific loss of function/potency” for sweeteners that bind to the VFTM.

Figure 3.

Effects of mutations of residues predicted to contribute to the binding of aspartame in the VFTM of human T1R2. Calcium assay dose–response curves for aspartame and cyclamate were calculated for T1R2 mutants (coexpressed with wild type T1R3 and Gα16-gus44). The responses were measured by the change in fluorescence over baseline following addition of sweetener and expressed as ΔF/F and normalized toward saturation. EC50 data are from dose–response curves of quadruplicate points from at least 3 separate experiments and expressed as mean ± SE in a log scale (see Supplemental Table 1 for values). The difference in EC50 of each mutant receptor from that of the wildtype receptor is shown as ΔEC50 in log molar concentration (see Materials and methods for more details). (A) A mutant’s positive shift of EC50 represents an increase in the EC50 value and a loss of apparent potency for aspartame and/or cyclamate, respectively, in comparison to WT. Strong EC50 shifts of aspartame compared with cyclamate are marked by a star (S40A, Y103, S144A S165I, D278A&N, E302Q, and E307N). Mutants greatly affected for both aspartame and cyclamate responses are symbolized by a cross (D142A/N, S168I, Y215A/H, D307A, and R383A/F). (B) Examples of saturation dose–response curves for aspartame in comparison to cyclamate for T1R2 mutants paired with hT1R3 (hT1R2 S40A, S165I, D278A and D278N, and D307N), data are from representative experiment(s).

The alanine mutants that displayed a dramatic decrease in both aspartame and cyclamate responsiveness were subsequently mutated more conservatively, retaining some properties of the original residue, and then reassayed for function (i.e., D142N, Y215H, and D307N). In addition to directly interacting residues, we also mutated selected neighborhood residues (up to 5Å distance) that had shown potential for allosteric effects on the ligand binding pocket and/or the ligand-induced receptor activation. The mutants shown in Figure 3 were characterized functionally; their activities fell into 3 broad categories: 1) specifically reduced responses to aspartame alone: S40A, Y103A, S144A, S165I, D278A/N, E302Q, and D307N; 2) no response or reduced response to both aspartame and cyclamate: D142A/N, Y215A/H, E302A, D307A, V309A, and R383A/F/K; 3) responses comparable to wildtype receptor: N44A, K65A, I67A, N143A, L279, and S303A. Therefore, S40, Y103, S144, S165, D278, E302, and D307 are implicated as specific sites of interaction within hT1R2’s VFTM for aspartame.

hT1R2’s VFTM residues D278 and D307 interact with aspartame’s NH moiety

In the refined docked model, the D278 side chain forms a hydrogen bond with the NH backbone peptide linkage of the ligand (Figure 4A). The D278A mutation reduces the receptor’s activity toward aspartame (Figure 3) as is predicted from the loss of this contact. Additional loss of cyclamate activity suggests D278’s potential participation in global signal transmission. The D278N mutation produces a substantial change in the receptor’s EC50 for aspartame (~2 orders of magnitude) with almost no loss of activity toward cyclamate.

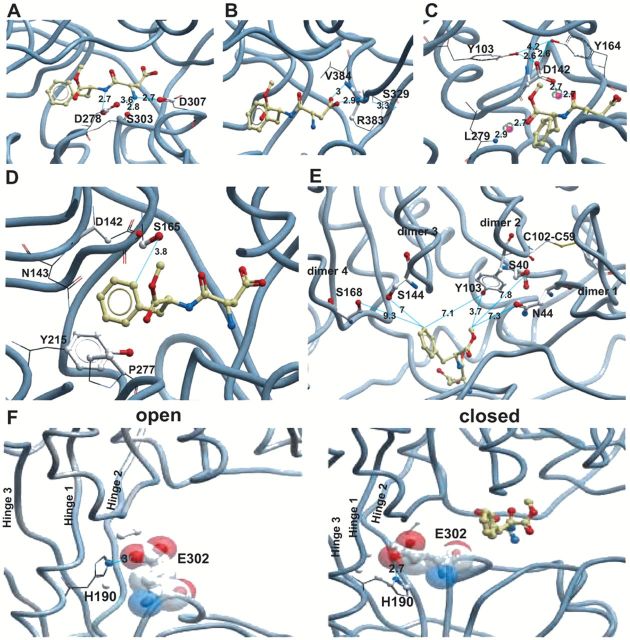

Figure 4.

Multiple views of the binding cleft of the VFTM of T1R2. (A) Frontal view of the closed binding cleft with lobe 1 at the top and lobe 2 at the bottom. Aspartame is shown in its docked position with the residues making contact with aspartame’s backbone nitrogens highlighted. Distances are shown in angstrom and indicated by lines. (B) Oblique view from the nondimerization side of the closed binding cleft with aspartame docked and showing the interactions with the aspartic acid sidechain oxygens of aspartame and the backbone nitrogens of R383 and V384 of T1R2. Also shown is the distance of the R383 sidechain to S329 in Å. (C) Oblique view from the nondimerization side of the closed binding cleft with aspartame docked and showing the interactions of T1R2’s D142 and L279 with aspartame’s backbone oxygens via 2 water molecules. Also shown are the distances between the sidechain of D142 and the 2 proximal tyrosines Y103 and Y164. (D) A view of docked aspartame from the front of the closed binding cleft showing interactions of aspartame’s phenyl ring with the cleft’s residues. Atoms within 4Å are shown as ball and stick with the remainder of each residue shown as sticks. (E) A view showing docked aspartame from the dimerization interface showing the position and relationship to aspartame of residues S40, N44, Y103, S144, and S168. (F) Looking from the dimerization interface, views of the open cleft and closed cleft (with aspartame docked) showing the change in orientation of E302 and its proximity to H190.

D307 is also predicted to interact with this NH group (Figure 4A), but the D307A mutation results in a receptor with equally reduced activity toward aspartame and cyclamate (Figure 3). The more conservative D307N mutant produces a smaller change in aspartame’s EC50 (~1 order of magnitude) than that of D307A but removes the effect of mutation on cyclamate. The NH group of aspartame is also predicted to interact with the backbone oxygen of S303; as expected, the S303A mutation has little effect on aspartame activity. K65A, which has been implicated in binding to sweet enhancers and in forming salt bridges with D278 and D307 in T1R2’s binding cleft when bound to sucralose and enhancer(s) (Zhang et al. 2010), had no significant effect on the activity of either aspartame or cyclamate.

hT1R2’s VFTM residues R383 and V384 are predicted to interact with aspartame’s carboxyl group

The negatively charged carboxyl group of aspartame is predicted to form 2 hydrogen bonds with the backbone NH atoms of R383 and V384 (Figure 4B). The interactions between the ligand and the backbone of the receptor residues cannot be tested by mutations unless the change in residue side chain is great enough to perturb the positioning of the main chain or destabilize important structural relationships within lobe 1. R383A or F mutants produced global deficits to both aspartame and cyclamate (Figure 3A) suggesting that this residue is an essential structural element within the heterodimer. Even the more conservative R383K mutant showed a global reduction in apparent affinity of approximately 1 log unit to both cyclamate and lactisole.

hT1R2’s VFTM residues D142 and L279 are predicted to interact with aspartame’s backbone oxygen atoms

The refined docked model predicts that 2 water molecules bridge the 2 backbone oxygen atoms of aspartame with residues D142 and L279 through hydrogen bonds (Figure 4C). D142A shifts the activity of both aspartame and cyclamate by nearly 2 log units, and the more conservative D142N substitution produces a mutant receptor that is even more insensitive to both compounds (shift of log(EC50) is >3 units—Figure 3A). L279 was also substituted with Ala because it is the backbone nitrogen that is implicated in ligand binding with L279, and, as expected, the Ala substitution had no significant impact on aspartame activity (Figure 3A).

hT1R2’s VFTM residue Y103 interacts with aspartame’s methyl group

Y103 is predicted by our model to provide hydrophobic interactions with the methyl group (C9) of aspartame (Figure 4C). The Y103A mutant receptor has greatly reduced apparent affinity for aspartame (>3 log units) with minimal effect on cyclamate activity (Figure 3A,B). This differs from the role proposed by Masuda et al. (2012), and suggests that Y103 has global importance for receptor activation by forming a hydrogen bond with D278 to stabilize the closed form of hT1R2.

hT1R2’s VFTM residue S165 interacts with aspartame’s phenyl ring

The refined docked model shows that the phenyl group of aspartame interacts with Y215 though π–π interactions and with P277, D142, N143, and S165 through hydrophobic interactions (Figure 4D). Attempts to characterize these interactions with D142A or D142N and Y215A or Y215H mutants were inconclusive as these mutants are insensitive to all sweeteners, therefore preventing the assessment of these interactions by experimental measurements (Figure 3A). N143A and S165A showed no change from wild type for either aspartame or cyclamate. This is supported by model predictions that a hydrophobic interaction with the side chain distal carbon atom of each residue may be adequately replaced by the hydrophobic contribution of the Ala substitution for each (Table 2). When S165 was substituted with the bulkier Ile, this mutant was specifically unresponsive to aspartame but nearly normal in its response to cyclamate. This suggests that the Ile substitution blocks aspartame’s access to the pocket.

hT1R2’s VFTM residues V66, S303, R383 are predicted to interact with aspartame’s backbone carbons

V66, S303, R383 are all predicted to contribute hydrophobic interactions to aspartame’s backbone carbons (C6 & C13—Table 2). It had been previously shown that V66 contributes to the species specificity for human versus monkeys in binding aspartame (Liu et al. 2011). Nearby reside I67 when substituted to mouse form (I67L) lost potency toward aspartame in comparison to cyclamate (Supplementary Table 1). The Ala substitution at S303 had, as reported above (Figure 3A), only a small effect on both cyclamate and aspartame. R383 substitutions are not tolerated by the receptor so this residue could not be assessed for its hydrophobic contributions to aspartame stability.

Effects of mutations to T1R2 VFTM residues that are not predicted to bind directly to aspartame

S40, N44, S144, and S168 are adjacent to the pocket and at the base of the 4 dimerization zones (Figure 4E). They were mutated to probe the requirements for communication between the binding pocket and the dimerization domain. S40, which lies “above” Y103 in lobe 1 at the leading edge of a loop that forms dimerization zone 1 and is well removed from the binding cleft, was mutated to Ala. Interestingly, this mutant receptor showed a large and highly specific reduction in activity toward aspartame, with no aspartame-induced activity even at the highest concentration used in our experiments. In contrast, N44A, (which lies “below” Y103 within the first dimerization zone loop), had no effect on either aspartame or cyclamate activity (Figure 3). S144, which lies at the base of helix C forming the third of 4 dimerization zones, when mutated to Ala also produced a large specific reduction in the apparent affinity for aspartame (~3 log units – Figure 3). When S168 was also substituted with Ile, this substitution resulted in a mutant receptor that was unresponsive to both cyclamate and aspartame.

Several mutations of E302, to Ala and Gln (Figure 3A), were made in order to investigate the role of this centrally located residue lying in 1 strand of the hinge in the “throat” of the binding pocket (Figure 4F). Our model of the closed binding site does not predict an interaction with E302 (Tables 1 and 2); however the homologous residue in the calcium sensing receptor is part of the binding site for calcium (Kunishima et al. 2000; Tsuchiya et al., 2002; Pin et al. 2003; Muto et al. 2007). The E302A mutant receptor had reduced sensitivity to both aspartame and cyclamate with a nearly 2-log unit EC50 decrease to both. The more conservative substitution to Glu produced a mutant which was wild type in its EC50 to cyclamate but had a >2 log unit reduction in sensitivity specifically to aspartame.

Discussion

In this study, we identified key binding site residues for the artificial sweetener aspartame using complementary computational and experimental approaches. In agreement with previous reports (Xu et al. 2004; Cui et al. 2006), our docking calculations indicated that the artificial sweetener aspartame binds to the closed form of hT1R2 VFTM in the active sweet receptor. The docked structures (verified experimentally) show that aspartame interacts with the sweet taste receptor through salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions, and that 2 water molecules may play an important role in sweetener binding by forming hydrogen-bond bridges between the sweetener and the receptor. It is known that the binding pocket of T1R2’s VFTM has multiple partially overlapping binding sites for different sweeteners (Kunishima et al. 2000; Tsuchiya et al. 2002; Muto et al. 2007). Investigating the involvement of water molecules in T1R2 binding to other classes of sweeteners could prove informative.

Contacts between T1R2 lobe 2 side chains and aspartame

Our refined docked models predict salt bridges between 2 of the nitrogen atoms of aspartame and the side chains of 2 aspartic acid residues (D278 and D307) in lobe 2 on the ‘lower’ surface of the binding cleft. While mutation of these residues to Ala gave nonspecific results, the more conservative mutations of each residue to Asn (D278N and D307N) showed specific effects for aspartame, while sparing cyclamate activity. This suggests that the charge is important for the side chain interaction with aspartame’s nitrogen, as is predicted by our model, but the steric size of the side chain is important for normal function of the mutant receptors. Because D307N mutation’s effect is less than that of either of the 2 D278 mutations, we believe D278 makes more significant contact with aspartame. Interestingly, the D278N mutation introduces the potential for a new N-linked glycosylation site. However, the peptide backbone at this site is oriented “inward,” (Figure 4A) and a glycan moiety would induce a significant conformational change. We find it unlikely that any activity for aspartame or cyclamate would remain under these circumstances, thus we feel it unlikely that this site is actually glycosylated.

Zhang et al. (2010) report that D278 forms a bond with K65 in a “pincer” action to aid in the closure of the VFTM using “charge reversal studies.” However, in our assays, K65A has no effect on either aspartame or cyclamate activity, suggesting that a positive charge at this residue isn’t required for normal activity of the sweet receptor. K65 lies in a potentially flexible loop that forms between the first dimerization domain and the first helix (Helix A) of lobe 1. The homology with mGluR is not precise at this position. In the alignment, T1R2 has an 8-residue loop, versus mGluR’s 7-residue sequence, between the conserved C59 and conserved G68 residues. In our model, the K65 side chain points toward the oxygen of Y357, part of the large nonhomologous loop that overhangs the mouth of the binding cleft. Inclusion of a negative charge at this position might disrupt the stability of this structure resulting in global disruption of function, which is then rescued by the double charge reversal as shown by Zhang et al.

Contacts between T1R2 lobe 2’s backbone and aspartame.

Other contacts between the receptor and aspartame are through hydrogen bonds to backbone atoms. Substitution of these residues, as expected, had little to no specific effects on aspartame activity. Mutations were either globally tolerated (S303A, L279A, and V384A) or were globally deleterious to both aspartame and cyclamate (R383 mutants).

Of particular importance is the side chain interaction predicted by our model between a backbone oxygen of aspartame and the side chain of D142 bridged by a water molecule (Figure 4C). We could not assess the importance of D142’s predicted contacts to aspartame via a water molecule due to the large deleterious effect of its mutants on overall function. We speculate that D142’s negative charge and size both play a role in either structural stability of the pocket or as a step in the transmission of the conformational change. D142A also fails to respond to sucralose, sucrose, and stevioside in the Senomyx studies (Zhang et al. 2010) but its loss can be compensated by enhancers SE-2 and SE-3 in combination with these sweeteners as well as by the proprietary sweetener SWT819. It would be interesting to ask whether D142N, with its greater impairment in response to aspartame in our study (Figure 3A), could be similarly compensated.

In addition to D142’s interaction with aspartame in our model, D142’s side chain is also close to the side chains of Y103, Y164, and S165. The Y103A mutant shows a specific and very large decrease in activity in response to aspartame. Y103A’s large effect on affinity may reflect its position at the base of the dimerization zone 2 of helix B (Kunishima et al. 2000; Tsuchiya et al. 2002; Muto et al. 2007) and dependence on stabilizing effects of D142. It is also possible that the inadequacy of the Ala substitution at Y103 is due to the greater predicted distance from the aspartame methyl group. Y164A mutant receptors show a one-log unit increase in apparent affinity for aspartame with little effect on cyclamate (data not shown) so it would be of interest to determine the effect of the double mutant D142A and Y164A on activity.

Effects of indirect aspartame binding amino acids on signal transmission

In addition to residues predicted to make direct contact with the dipeptide sweeteners, we also explored the roles of residues nearby the binding pocket that might contribute to signal transmission in the dimer interface. An examination of the model suggests that S40 is located in a region that is critical for communication between the binding pocket and the dimerization zone that is known to reorder upon receptor activation. S40 is “above” Y103 and adjacent to 1 of 2 cysteines that stabilizes dimer loop 1. The loss of the hydroxyl at S40 in mutants might disrupt the signal between Y103 and the dimer zone upon ligand binding within the cleft, thus explaining the large reduction in activity toward cyclamate of the S40A mutant (Figure 3).

We wanted to test the idea that residues proximal to the binding pocket and the dimer domain loops can alter the activation profile of ligands that bind within the cleft region. Mutation of S168 to Ile was not tolerated, and activity to both aspartame and cyclamate was lost. The substitution may have created too much rigidity at the base of dimer loop 4, especially because it lies next to I167, and the consecutive isoleucine residues would be expected to form a rigid backbone segment. This suggests that the mobility and structural integrity of these 2 dimer zones is required for proper translation to the active conformation of the receptor (Figure 4E).

S144, which lies at the base of helix C in the third dimerization segment, when mutated to Ala, shows a loss of at least 2 log units of apparent affinity for aspartame even though it is not predicted to contact the ligand. In the ligand-bound, closed cleft state, S144’s hydroxyl is within 4 angstroms of Y215’s backbone nitrogen. This potential interaction may help to stabilize the binding cleft when aspartame is present or participate in the propagation of the signal. We were not able to test our model’s prediction of interactions between Y215 and other residues due to Y215A and Y215H mutants being insensitive to all sweeteners. Future studies with Y215F and Y215W could be useful because these mutations should maintain or even strengthen the Y215’s proposed π–π interactions.

E302 resides in the “throat” of the cleft in the second of the 3 lobe-spanning strands that form the hinge that permits the relative motion of the 2 lobes toward each other in the “closed” state (Figure 4F). E302 mutants had large effects on ligand binding despite its lack of contact with aspartame in our refined docked models of the closed ligand bound receptor. E302A’s effect was general with almost a 2-log unit loss in affinity for both aspartame and cyclamate, while the more conservative E302Q mutant’s response was specific to aspartame (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the Masuda et al. model (Masuda et al. 2012), which predicts E302 to form salt bridges with the charged amine group of aspartame, would not support the global reduction in activity of the E302A mutant. In contrast, E302Q displayed markedly reduced potency toward aspartame, but kept responsiveness to cyclamate. This suggests that E302 plays a structural role in the hinge (E302A disrupts this) and also a specific but currently unknown role in binding and activation of the receptor by aspartame (E302Q disrupts this). Further examination (Figure 4F) shows that the side chain oxygens of E302 are just 2.7Å from H190 in the closed form (versus 6Å in the open form) and may form a salt bridge if H190 is protonated. H190 lies in helix D just proximal to the beta strand that forms the first of the 3 hinge strands. In the open model, E302 faces into the cleft and might participate in an intermediate binding site for some ligands. If this configuration is correct, we might expect that when E302 encounters a ligand, an interaction with H190 is induced. This modification might help to stabilize hinge bending and lead to cleft closure. In support of this idea, the H190A mutant is a nonresponsive receptor (data not shown). Clearly this hypothesis warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, we have identified the residues necessary for aspartame binding within and proximal to the ligand binding cleft of T1R2. These studies have also started to trace the pathway from ligand binding to protomer closure and rotation of the dimerization domain that is required for activation by these and other sweet-tasting compounds.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material can be found at http://www.chemse.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DC007721 to M.C., DC007021 to P.J. and E.L.M., DC006696 to M.M., DC008301 to E.L.M. and M.M., DC03155 to R.F.M., and DK43036 to R.O.) and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (MCB060020P and MCB070095T to M.C.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Claude Nofre for helpful discussions.

References

- Amrein H, Bray S. 2003. Bitter-sweet solution in taste transduction. Cell. 112(3):283–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assadi-Porter FM, Maillet EL, Radek JT, Quijada J, Markley JL, Max M. 2010. Key amino acid residues involved in multi-point binding interactions between brazzein, a sweet protein, and the T1R2–T1R3 human sweet receptor. J Mol Biol. 398:584–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. 2008. Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 32:20–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Tordoff MG, Beauchamp GK. 2001. Sweetener preference of C57BL/6ByJ and 129P3/J mice. Chem Sens. 26:905–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie JU, Luthy R, Eisenberg D. 1991. A method to identify protein sequences that fold into a known 3-dimensional structure. Science. 253:164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breneman CM, Wiberg KB. 1990. Determining atom-centered monopoles from molecular electrostatic potentials—the need for high sampling density in formamide conformational-analysis. J Comput Chem. 11:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. 1983. CHARMM—a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J Comput Chem. 4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Jiang PH, Maillet E, Max M, Margolskee RF, Osman R. 2006. The heterodimeric sweet taste receptor has multiple potential ligand binding sites. Curr Pharm Des. 12:4591–4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Zakrzewski VG, Montgomery JA, Stratmann J, Burant JC, et al. 2002. Gaussian 98. Pittsburgh, PA: Gaussian, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Goodsell DS, Morris GM, Olson AJ. 1996. Automated docking of flexible ligands: applications of AutoDock. J Mol Recognit. 9:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet C, Kniazeff J, Hlavackova V, Malhaire F, Maurel D, Acher F, Blahos J, Prezeau L, Pin JP. 2005. Asymmetric functioning of dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptors disclosed by positive allosteric modulators. J Biol Chem. 280:24380–24385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer BR, Taylor-Burds CC, Mitzelfelt JD, Delay ER. 2004. Monosodium glutamate and sweet taste: discrimination between the tastes of sweet stimuli and glutamate in rats. Chem Senses. 29: 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Cui M, Ji Q, Snyder L, Liu Z, Benard L, Margolskee RF, Osman R, Max M. 2005a. Molecular mechanisms of sweet receptor function. Chem Sens. 30:I17–I18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang PH, Cui M, Zhao BH, Liu Z, Snyder LA, Benard LMJ, Osman R, Margolskee RF, Max M. 2005b. Lactisole interacts with the transmembrane domains of human T1R3 to inhibit sweet taste. J Biol Chem. 280:15238–15246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang PH, Cui M, Zhao BH, Snyder LA, Benard LMJ, Osman R, Max M, Margolskee RF. 2005c. Identification of the cyclamate interaction site within the transmembrane domain of the human sweet taste receptor subunit T1R3. J Biol Chem. 280:34296–34305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang PH, Ji QZ, Liu Z, Snyder LA, Benard LMJ, Margolskee RF, Max M. 2004. The cysteine-rich region of T1R3 determines responses to intensely sweet proteins. J Biol Chem. 279:45068–45075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jingami H, Nakanishi S, Morikawa K. 2003. Structure of the metabotropic glutamate receptor. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 13:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Kusakabe Y, Miura H, Ninomiya Y, Hino A. 2001. Molecular genetic identification of a candidate receptor gene for sweet taste. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 283:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishima N, Shimada Y, Tsuji Y, Sato T, Yamamoto M, Kumasaka T, Nakanishi S, Jingami H, Morikawa K. 2000. Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature. 407:971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XD, Staszewski L, Xu H, Durick K, Zoller M, Adler E. 2002. Human receptors for sweet and umami taste. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99:4692–4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann B. 1996. Taste reception. Physiol Rev. 76:719–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Ha M, Meng XY, Kaur T, Khaleduzzaman M, Zhang Z, Jiang P, Li X, Cui M. 2011. Molecular mechanism of species-dependent sweet taste toward artificial sweeteners. J Neurosci. 31:11070–11076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthy R, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D. 1992. Assessment of protein models with 3-dimensional profiles. Nature. 356:83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolskee RF. 2002. Molecular mechanisms of bitter and sweet taste transduction. J Biol Chem. 277:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sanchez R, Melo F, Sali A. 2000. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 29:291–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda K, Koizumi A, Nakajima K, Tanaka T, Abe K, Misaka T, Ishiguro M. 2012. Characterization of the modes of binding between human sweet taste receptor and low-molecular-weight sweet compounds. PLoS One. 7:e35380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max M, Shanker YG, Huang LQ, Rong M, Liu Z, Campagne F, Weinstein H, Damak S, Margolskee RF. 2001. Tas1r3, encoding a new candidate taste receptor, is allelic to the sweet responsiveness locus Sac. Nat Genet. 28:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur RH, Schlatte J, Goldkamp AH. 1969. Structure–taste relationships of some dipeptides. J Am Chem Soc. 91:2684–2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald IK, Thornton JM. 1994. Satisfying hydrogen-bonding potential in proteins. J Mol Biol. 238:777–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguro T, Kashiwagi T, Satow Y. 2000. Crystal structure of the low-humidity form of aspartame sweetener. J Pept Res. 56:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montmayeur JP, Liberles SD, Matsunami H, Buck LB. 2001. A candidate taste receptor gene near a sweet taste locus. Nat Neurosci. 4:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. 1998. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Muto T, Tsuchiya D, Morikawa K, Jingami H. 2007. Structures of the extracellular regions of the group II/III metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:3759–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Zhang YF, Ryba NJP, Zuker CS. 2001. Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell. 106:381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Galvez T, Prezeau L. 2003. Evolution, structure, and activation mechanism of family 3/C G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 98:325–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell TL. 1993. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 234:779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman SS, Booth BJ, Sattely-Miller EA, Graham BG, Gibes KM. 1999. Selective inhibition of sweetness by the sodium salt of +/− 2-(4-methoxyphenoxy)propanoic acid. Chem Sens. 24:439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani A, Abrams M. 1986. Rats show only a weak preference for the artificial sweetener aspartame. Physiol Behav. 37:253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani A, Perez C. 1997. Cypha(TM) propionic acid, 2-(4-methoxyphenol) salt inhibits sweet taste in humans, but not in rats. Physiol Behav. 61:25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack JP. 2009. Functional method to identify tastants. US patent application US 12/297,695. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. Clustal-W—improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya D, Kunishima N, Kamiya N, Jingami H, Morikawa K. 2002. Structural views of the ligand-binding cores of a metabotropic glutamate receptor complexed with an antagonist and both glutamate and Gd3+. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99:2660–2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda T, Ugawa S, Yamamura H, Imaizumi Y, Shimada S. 2003. Functional interaction between T2R taste receptors and G-protein alpha subunits expressed in taste receptor cells. J Neurosci. 23:7376–7380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner MW. 1971. Comparative rodent preferences for artificial sweeteners. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 75:483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. 1995. LIGPLOT—a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 8:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnig M, Bufe B, Meyerhof W. 2005. Valine 738 and lysine 735 in the fifth transmembrane domain of rTas1r3 mediate insensitivity towards lactisole of the rat sweet taste receptor. BMC Neurosci. 6:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Staszewski L, Tang H, Adler E, Zoller M, Li X. 2004. Different functional roles of T1R subunits in the heteromeric taste receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101:14258–14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Klebansky B, Fine RM, Liu HT, Xu H, Servant G, Zoller M, Tachdjian C, Li XD. 2010. Molecular mechanism of the sweet taste enhancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:4752–4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GQ, Zhang YF, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, Ryba NJP, Zuker CS. 2003. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell. 115:255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.