Abstract

The proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter (POT/PTR) family shares a highly conserved E1X1X2E2RFXYY (E1X1X2E2R) motif across all kingdoms of life. This motif is suggested to have a role in proton coupling and active transport in bacterial homologs. For the plant POT/PTR family, also known as the NRT1/PTR family (NPF), little is known about the role of the E1X1X2E2R motif. Moreover, nothing is known about the role of the X1 and X2 residues within the E1X1X2E2R motif. We used NPF2.11—a proton-coupled glucosinolate (GLS) symporter from Arabidopsis thaliana—to investigate the role of the E1X1X2E2K motif variant in a plant NPF transporter. Using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based uptake assays and two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) electrophysiology, we demonstrate an essential role for the E1X1X2E2K motif for accumulation of substrate by NPF2.11. Our data suggest that the highly conserved E1, E2 and K residues are involved in translocation of protons, as has been proposed for the E1X1X2E2R motif in bacteria. Furthermore, we show that the two residues X1 and X2 in the E1X1X2E2[K/R] motif are conserved as uncharged amino acids in POT/PTRs from bacteria to mammals and that introducing a positive or negative charge in either position hampers the ability to overaccumulate substrate relative to the assay medium. We hypothesize that introducing a charge at X1 and X2 interferes with the function of the conserved glutamate and lysine residues of the E1X1X2E2K motif and affects the mechanism behind proton coupling.

Keywords: Defense compound transporters, EXXERFYY motif, NPF2.11, POTs, Proton-coupling, TEVC electrophysiology

Introduction

The proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter (POT/PTR) family of transporters are H+/substrate symporters found across all kingdoms of life (Daniel et al. 2006, Leran et al. 2014). The POT/PTR family is hypothesized to utilize a common alternating-access transport mechanism, in which two six-transmembrane domain bundles flip around a central substrate-binding cavity. This leads to alternating access of the substrate-binding cavity to either the exterior or interior of the cell, with an intermediate step where the substrate cavity is occluded (reviewed by Law et al. 2008, Forrest et al. 2011, Newstead 2015). POT/PTR transporters share a highly conserved E1X1X2E2RFXYY motif (E1X1X2E2R) (Daniel et al. 2006, Newstead 2015). In the bacterial PepTSt transporter, this motif was suggested to have an important role in proton coupling (Solcan et al. 2012). In a recent mutational study of the plant nitrate transporter NRT1.1 (NPF6.3), removal of charged residues in the E1X1X2E2R motif abolished nitrate ion transport (Sun et al. 2014). Apart from this study, the role of the E1X1X2E2R motif in the plant NRT1/PTR family (NPF) remains poorly characterized and, moreover, the importance of the two amino acid positions denoted by X remains unknown.

The Arabidopsis thaliana genome encodes 53 members of the NPF of transporters characterized by highly diverse substrate specificities spanning from specialized metabolites such as glucosinolates (GLS) (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012) and plant phytohormones (auxin and ABA) (Krouk et al. 2010, Kanno et al. 2012), to primary metabolites, e.g. di- and tripeptides (Dietrich et al. 2004, Komarova et al. 2008, Weichert et al. 2012) and the nitrate ion (Tsay et al. 1993). Among the A. thaliana NPF transporters, two versions of the E1X1X2E2R motif occur, with either a terminal lysine or a terminal arginine. To date, the E1X1X2E2K motif has not been functionally characterized.

In this study, we investigated the role of the E1X1X2E2K motif variant E57T58F59E60K61 found in NPF2.11, a plasma membrane-localized, high-affinity H+/GLS symporter (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012). By mutating key residues of the E1X1X2E2K motif and characterizing mutant transporters by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) electrophysiology, we showed that the E1X1X2E2K motif was essential for overaccumulation of GLS substrate relative to the assay medium. Furthermore, we demonstrated that positions X1 and X2 influenced the transport properties of NPF2.11 and appeared constrained as neutral residues. How X1 and X2 may influence the transport mechanism is discussed.

Results

Charged residues in the E57T58F59E60K61 motif are required for overaccumulation relative to the assay medium

NPF2.11 is a H+/GLS symporter that utilizes the inwardly directed proton electrochemical gradient (ΔµH+) between the plant apoplast (pH5.5) and cytoplasm (pH 7.4) to drive the import of GLS (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012). Here we tested the ability of NPF2.11 to accumulate 4-methylsulfinylbutyl glucosinolate (4MTB) relative to the assay medium. LC-MS analysis of extracts from Xenopus oocytes expressing NPF2.11 showed overaccumulation of 4MTB to levels several fold higher than the concentration in the assay medium (Fig. 1A). The absolute overaccumulation depended on assay time and varied between oocyte batches. This is exemplified with a 3-fold overaccumulation after 1 h uptake (Fig. 1A) and a 10-fold overaccumulation after 1 h (Fig. 6B). We proceeded by substituting the three charged residues in the NPF2.11-E57T58F59E60K61 motif to alanine. The mutant versions were expressed in X. laevis oocytes and effects on transport activity were characterized using LC-MS-based uptake assays and TEVC electrophysiology (see Fig. 1C for a model of NPF2.11 with Glu57, Glu60 and Lys61 highlighted).

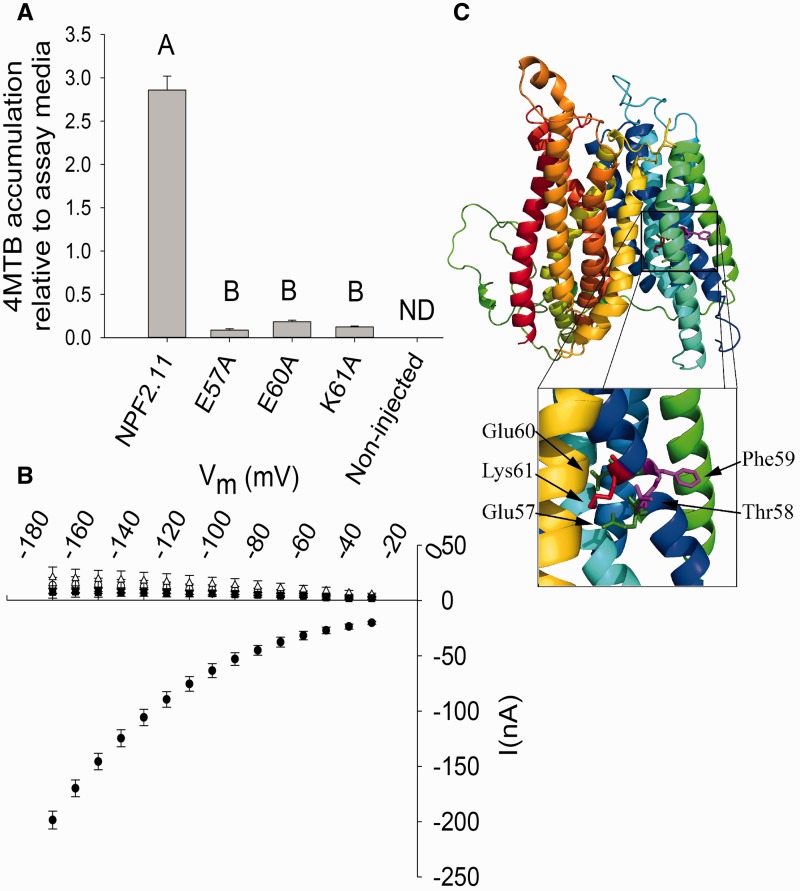

Fig. 1.

Transport activity of epitope-tagged NPF2.11-E57T58F59E60K61 mutants. (A) Fold 4MTB accumulation relative to the 4MTB concentration in the assay medium in X. laevis oocytes expressing NPF2.11, NPF2.11-E57A, NPF2.11-E60A or NPF2.11-K61A. Groups are determined by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) vs. NPF2.11 (error bars: SD, n = 3). ND, none detected. 4MTB content was quantified by LC-MS in 3 × 5 oocytes from one batch for each gene. (B) Current–voltage (I–V) curve of NPF2.11 (filled circles), NPF2.11-E57A (open circles), NPF2.11-E60A (open inverted triangle), NPF2.11-K61A (open upright triangle) and non-injected (filled squares) oocytes exposed to 200 mM 4MTB (bars are averages; error bars: SD, n = 3 oocytes). (C) NPF2.11 homology model with the highlighted E57T58F59E60K61 motif. The insert shows a close-up of the E57T58F59E60K61 motif with Glu57 and Glu60 highlighted in green, Thr58 and Phe59 highlighted in magenta and Lys61 highlighted in red.

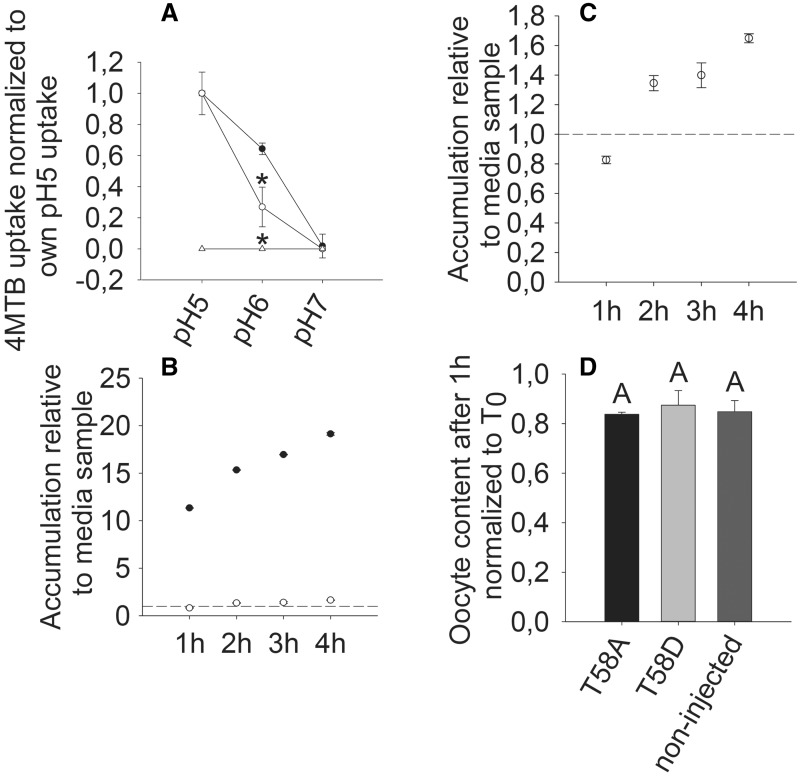

Fig. 6.

pH dependency, 4MTB accumulation over time and export of 4MTB. (A) Relative 4MTB transport by NPF2.11-expressing (filled circles), T58D-expressing (open circles) or non-injected (open triangles) oocytes as a function of pH when exposed to 100 mM 4MTB. 4MTB content was quantified by LC-MS in 3 × 5 oocytes for each gene. No uptake of 4MTB was detected in non-injected oocytes. Experiments were repeated twice with independent batches of X. laevis oocytes with similar results. Data presented are from one batch of oocytes. Groups are determined by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) vs. NPF2.11. Error bars: SD, n = 3. (B) Fold 4MTB accumulation in X. laevis oocytes expressing NPF2.11 (filled circles) or T58D (open circles) relative to the 4MTB concentration in the assay medium (dotted line). 4MTB content was quantified by LC-MS in 3 × 5 oocytes for each gene. Error bars: SD, n = 3 × 5 oocytes. (C) The same as (B), showing only T58D (open circles) uptake. (D) 4MTB GLS content in T58A-expressing, T58D-expressing and non-injected oocytes after injection of 4MTB to a calculated concentration of 1 mM and incubation in Kulori buffer pH 5 for 1 h. 4MTB content quantified by LC-MS in 3 × 5 oocytes for each gene is depicted relative to 4MTB content at time 0. Groups are determined by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) vs. NPF2.11. Error bars: SD, n = 3.

NPF2.11 mutants E57A, E60A and K61A were capable of transporting 4MTB into oocytes; however, the accumulation relative to that of external medium after 1 h of incubation was reduced to 0.1–0.2 (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, currents elicited from oocytes expressing E57A, E60A and K61A were indistinguishable from background currents of non-injected oocytes (Fig. 1B).

Sequence analysis of the Arabidopsis NPF family E1X1X2E2R motif

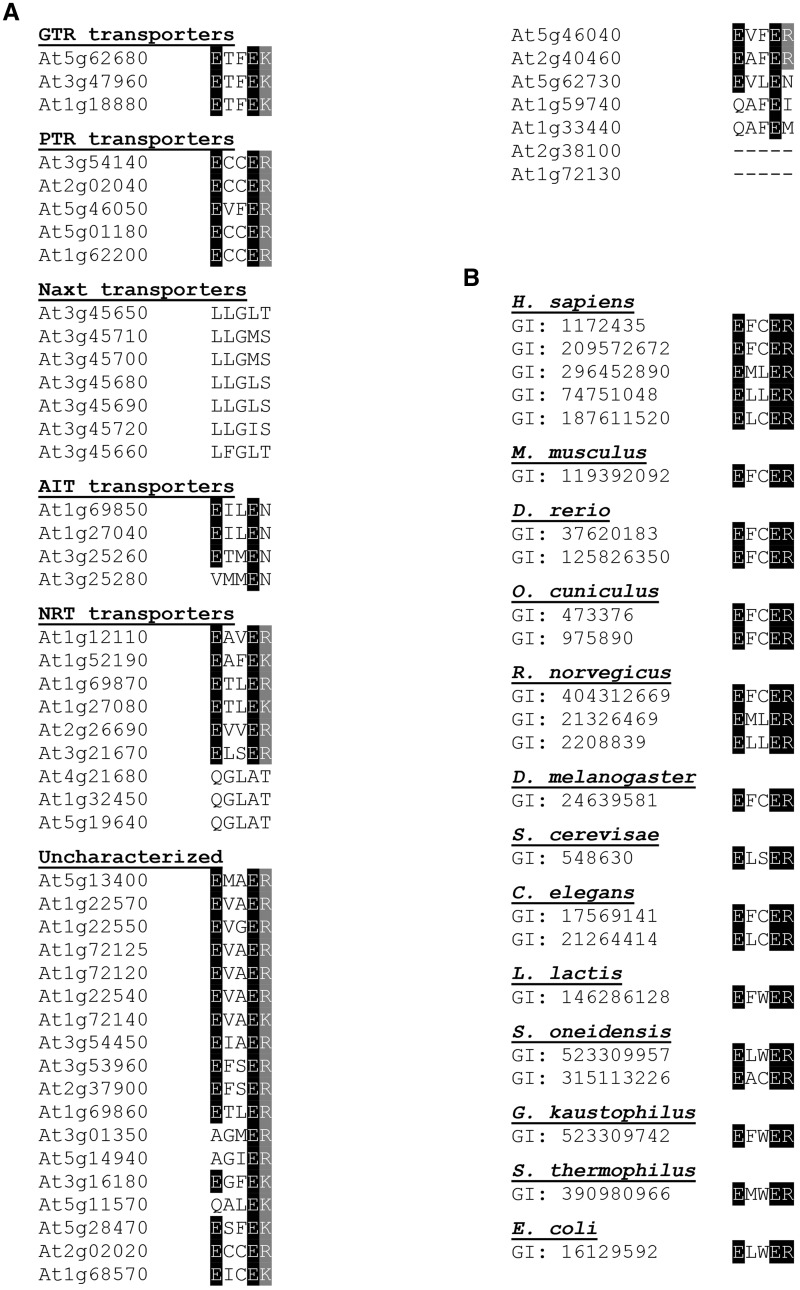

The roles of the second and third residue (X1 and X2) in the E1X1X2E2[K/R] motif are unknown, and no mutants in these residues, in any POT/PTR gene, have been characterized to date. The denotation by X indicates that these residues could be occupied by any amino acid. We aligned the E1X1X2E2[K/R] motifs in the 53 members of the A. thaliana NPF of transporters and homologs from bacterial, fungal, worm and human POT/PTR transporters. A subset of the NPF does not encode the canonical E1X1X2E2[K/R] motif (Fig. 2), as also previously reported (Sun et al. 2014). These belong to the NAXT and NRT1.5 subclades (At1g32450, At4g21680 and At5g19640), which appear to encode nitrate transporters (Segonzac et al. 2007, Lin et al. 2008, Li et al. 2010). Among the NPF transporters and POT/PTR homologs encoding the canonical E1X1X2E2[K/R] motif, none contained a charged amino acid in either of the X positions (Fig. 2), suggesting an evolutionary constraint enforced on these residues. In consequence, we hypothesized that the X1 and X2 residues have an important role as uncharged residues to avoid interfering with the E1X1X2E2[K/R] motif and thus the proton-coupling mechanism.

Fig. 2.

Alignment of the E1X1X2E2[K/R] motifs of the 53 Arabidopsis NPF transporters and characterized bacterial, fungal, worm and mammalian POT/PTR transporters. Highlighted in black and gray are, respectively, conserved glumine residues and the less conserved arginine and lysine residues. (A) Aligned E1X1X2E2[K/R] motifs from 53 Arabidopsis transporters that are grouped based on experimental characterization. Abbreviations: ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA GLUCOSINOLATE TRANSPORTER (GTR) (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012), NITRATE EXCRETION TRANSPORTERs (NAXT) (Segonzac et al. 2007), ABA-IMPORTING TRANSPORTER (AIT) (Kanno et al. 2012) and NITRATE TRANSPORTERS (NRT) (Tsay et al. 1993, Chiu et al. 2004, Almagro et al. 2008, Fan et al. 2009, Li et al. 2010, Wang and Tsay 2011, Hsu and Tsay 2013). (B) Alignment of the E1X1X2E2R motifs from characterized bacterial, fungal, worm and mammalian POT/PTR transporters. Transporters are identified by gene identifier code (GI) and grouped based on species. Transporters have previously been described (Daniel et al. 2006a, Newstead et al. 2011, Solcan et al. 2012, Doki et al. 2013, Guettou et al. 2013).

Mutations of Thr58 and Phe59 abolish the ability to overaccumulate substrate

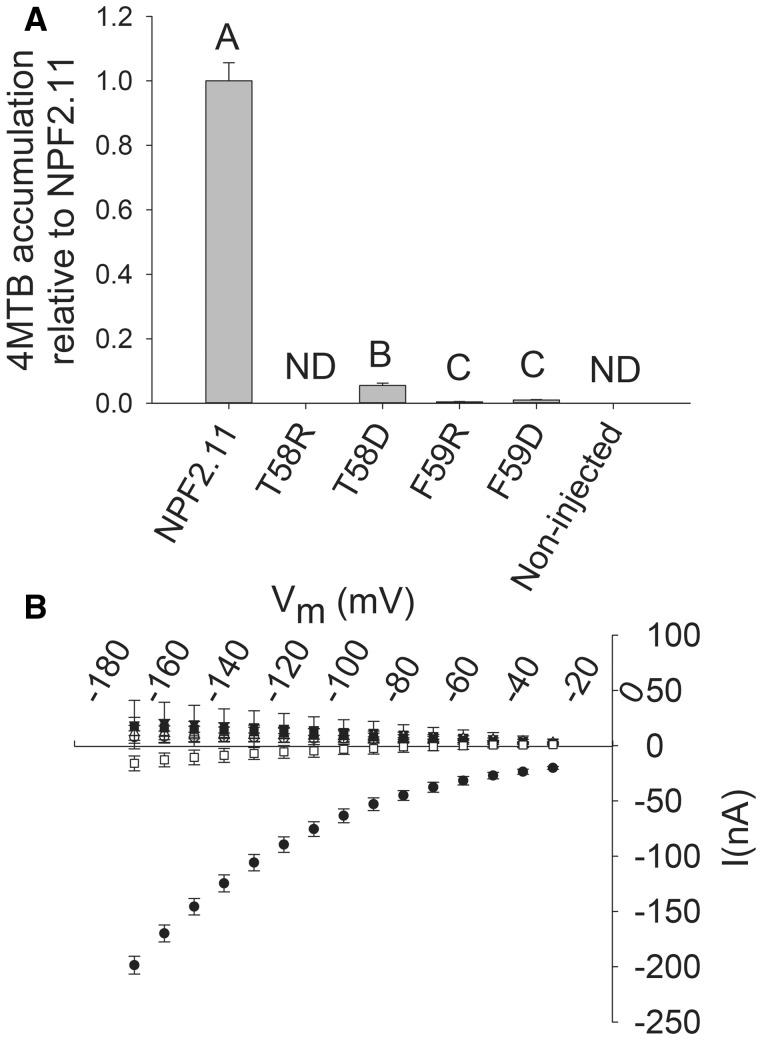

Introduction of charged residues instead of T58 or F59 in the NPF2.11-E57T58F59E60K61 motif was performed to test the hypothesis that position X1 and X2 are evolutionarily constrained as uncharged residues to avoid disruption of the proton-coupling mechanism. Mutation of F59 to either a positive residue (arginine) or a negative residue (aspartate) and of T58 to a positive (arginine) residue completely abolished 4MTB accumulation in oocytes (Fig. 3A) and resulted in 4MTB-induced currents indistinguishable from background currents in non-injected oocytes (Fig. 3B). In comparison, the NPF2.11-T58D (T58D) mutant transported 4MTB into oocytes, but accumulation after 1 h was only 10% of NPF2.11 uptake (Fig. 3A). Like the other mutants, T58D did not elicit 4MTB-induced currents (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Transport activity of epitope-tagged NPF2.11-E57T58F59E60K61 mutants. (A) Fold 4MTB accumulation relative to NPF2.11 levels in X. laevis oocytes expressing: NPF2.11, F59R, F59D, T58R or T58D, or non-injected oocytes. 4MTB content was quantified by LC-MS in 3 × 5 oocytes from one batch for each gene. Bars are the average; error bars: SD (n = 3). Groups are determined by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) vs. NPF2.11 (error bars: SD, n = 3). ND, none detected. (B) I–V curve of NPF2.11 (filled circles), T58D (inverted open triangles), T58R (upright open triangles), F59D (filled squares), F59R (open squares) and non-injected (open circles) oocytes exposed to 100 mM 4MTB (error bars: SD, n = 3 oocytes).

The reduced and apparent non-electrogenic transport activity of the T58D mutant prompted further characterization to reveal the role of the uncharged X1 and X2 residues in the NPF2.11-E57T58F59E60K61 motif with regards to pH dependency, and the ability to overaccumulate substrate.

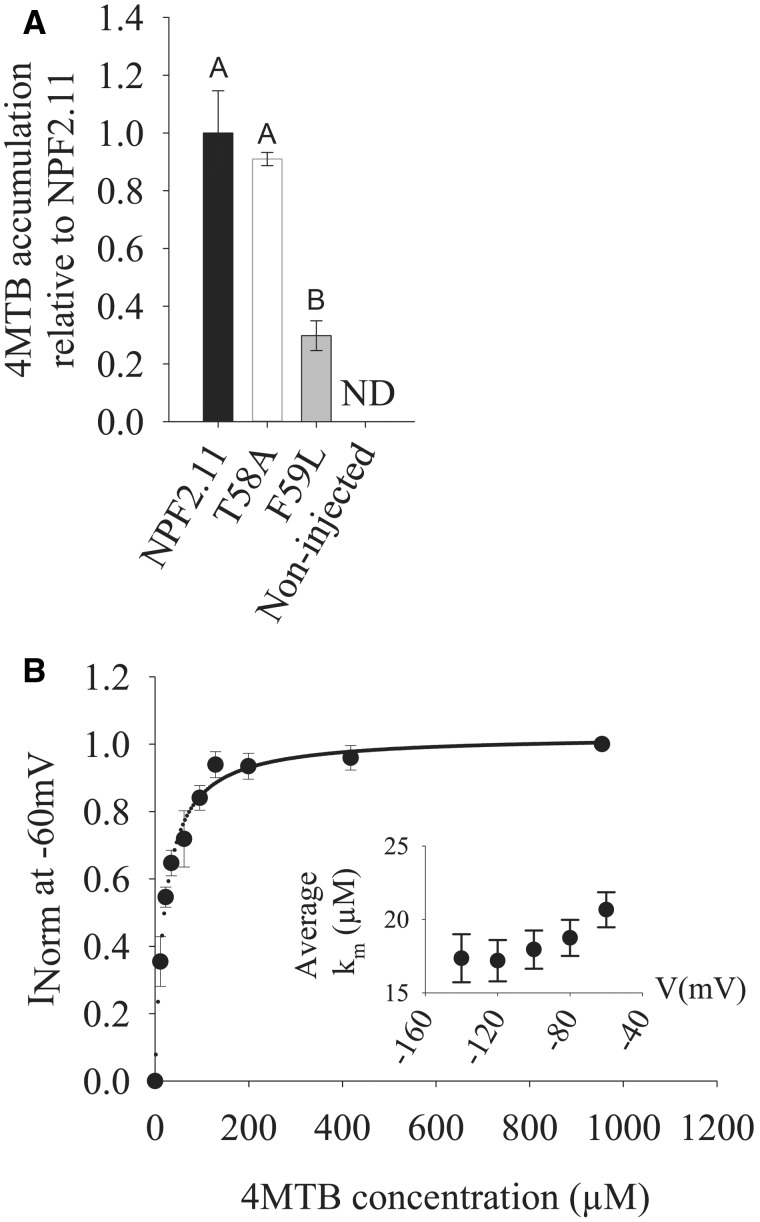

Thr58 is not essential for transporter function

T58 was mutated to a less bulky alanine residue, and the transport activity and kinetics of the NPF2.11-T58A mutant were measured by LC-MS-based uptake assays and TEVC electrophysiology. T58A elicited quantifiable 4MTB-induced currents that enabled determination of its affinity constant towards 4MTB. Plotting currents at –60 mV as a function of increasing 4MTB concentrations yielded a saturation curve, which was fitted by a Michaelis–Menten equation with an apparent affinity constant (Km) of 20.7 ± 1.0 µM and similar 4MTB uptake per oocyte as NPF2.11 (Fig. 4). The Km value is identical to those elicited by wild-type NPF2.11 protein when expressed in oocytes (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012). In contrast, mutation of F59 to leucine caused a decrease in 4MTB transport to 25% of NPF2.11 uptake, indicating that a phenylalanine at position X2 is integral for a functional NPF2.11 (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

4MTB uptake of epitope-tagged T58A- and F59L-expressing oocytes and TEVC measurements of epitope-tagged T58A-expressing oocytes. (A) YFP- or HA-fused NPF2.11, T58A and F59L were expressed separately in 15 Xenopus oocytes, and transport activity was measured in the presence of saturating 4MTB concentrations. 4MTB content quantified by LC-MS in 3 × 5 oocytes for each gene is depicted relative to the content in NPF2.11-injected oocytes. Groups are determined by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) vs. NPF2.11 (error bars: SD, n = 3). ND, none detected. (B) Kinetic analysis of T58A. Normalized 4MTB-dependent currents measured at a membrane potential of –60 mV and pH 5 were plotted against increasing 4MTB concentrations. The saturation curve was fitted with a Michaelis–Menten equation (solid line, error bars are SE, n = 5 oocytes). Each oocyte data set was normalized to currents elicited at saturating 4MTB concentration. The insert shows the apparent Km as a function of membrane potential.

Does T58D have a reduced expression level?

An alternative cause for reduced transport activity of T58D could be a reduced expression or changed localization (e.g. to oocyte endomembranes). In one experiment, single oocytes expressing T58A or T58D and non-injected oocytes were analyzed for 4MTB-induced currents and protein expression by Western blot (Fig. 5). T58D-expressing oocytes did not elicit any 4MTB-induced currents, whereas T58A-expressing oocytes had wild-type-like induced currents (Fig. 5A). No significant difference was observed when expression levels of T58A and T58D were quantified by densitometric analysis (Fig. 5C). In a subsequent experiment, localization of T58A and T58D was determined using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Both proteins associated with the periphery of the X. laevis oocytes, indicating an identical localization to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5D–F).

Fig. 5.

Expression levels, transport activity and localization of YFP-tagged NPF2.11 and T58D. (A) I–V curve of T58A- (filled circles) and T58D- (inverted open triangles) expressing oocytes exposed to saturating 4MTB concentrations. Non-injected oocytes were used as control (upright open triangles). Bars are the average; error bars: SD, n = 5. These oocytes were also used to quantify expression levels of T58A and T58D in (B) and (C). (B) Western blots showing expression of T58A and T58D. (C) Densitometric quantification of Western blots relative to endogenous actin levels in X. laevis oocytes used for TEVC measurements (error bars: SD, n = 5). (D–F) NPF2.11 and T58D localization in X. laevis oocytes (YFP fluorescence on the left and brightfield on the right). (D) Fixed oocytes expressing NPF2.11::YFP. (E) Fixed oocytes expressing T58D::YFP. (F) Fixed non-injected control oocytes.

Does the charge mutant T58D have altered pH dependency?

We investigated the relative pH dependency of NPF2.11 and T58D transport by conventional LC-MS-based uptake assays because 4MTB-induced currents of T58D-expressing oocytes were below the detection limit. The uptake activity of T58D-expressing oocytes was very low relative to that of NPF2.11-expressing oocytes at all pH values. Therefore, to compare pH dependency between NPF2.11 and T58D, accumulation at pH 5, pH 6 and pH 7 was normalized to the uptake at pH 5 for each transporter. For both NPF2.11 and T58D, uptake at pH 7 was below the detection limit (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, at pH 6, T58D-expressing oocytes had a significantly lower relative uptake of 4MTB compared with oocytes expressing NPF2.11. This indicates that insertion of an aspartate residue at this position could influence the pKa of E57 (the closest amino acid of the NPF2.11-E57T58F59E60K61 motif).

Is T58D a passive facilitator?

We speculated that the T58D mutation could have transformed the NPF2.11 transporter into a passive facilitator of 4MTB; therefore, we investigated the concentration of imported 4MTB over time. After incubation in 100 µM 4MTB for 1 h, oocytes expressing NPF2.11 contained an 11-fold higher concentration of 4MTB compared with the external assay medium. In comparison, oocytes expressing T58D only contained 0.7 times the concentration of the external medium (Fig. 6B, C). Non-injected oocytes did not accumulate GLS above the detection level at any time point during the 4 h uptake assay (data not shown). The internal concentration of 4MTB in oocytes expressing NPF2.11 relative to the concentration of the external assay medium increased to approximately 10-fold after 1 h incubation and continued to increase to 19-fold after 4 h incubation. For oocytes expressing T58D, the internal concentration of 4MTB after 1 h incubation was 0.7-fold relative to that in the external assay medium. After 4 h, the internal concentration of 4MTB was only approximately 1.6-fold relative to concentration in the the external medium (Fig. 6C). This indicates that the T58D mutant is still able to overaccumulate 4MTB relative to the concentration in the external assay medium but at a severely reduced rate.

Finally, we tested whether the T58D mutation rendered the transport protein capable of transporting 4MTB out of the cell against a proton gradient. 4MTB was injected into oocytes to an estimated internal concentration of 1 mM in T58A-expressing, T58D-expressing and non-expressing oocytes. The 4MTB-injected oocytes were incubated for 1 h in 4-MTB-free Kulori pH 5 buffer, and subsequently the internal 4MTB content was measured. During the 1 h assay, both T58A- and T58D-expressing oocytes as well as non-expressing oocytes lost approximately 20% of the injected 4MTB relative to T0 (control oocytes injected with 4MTB that were analyzed for 4MTB content immediately after injection). Loss of 4MTB in non-expressing oocytes probably occurs because the injection wound does not close immediately. Consequently, a small proportion of the injected 4MTB is expected to be lost from the oocyte during the assay. However, it is possible that the apparent efflux of injected 4MTB may be caused by a carrier endogenous to X. laevis oocytes that facilitates export of GLS. We did not measure a significant difference in 4MTB content of the T58A-expressing, T58D-expressing and non-expressing oocytes (Fig. 6D), which indicates that neither the T58D nor the T58A mutant facilitates additional 4MTB efflux.

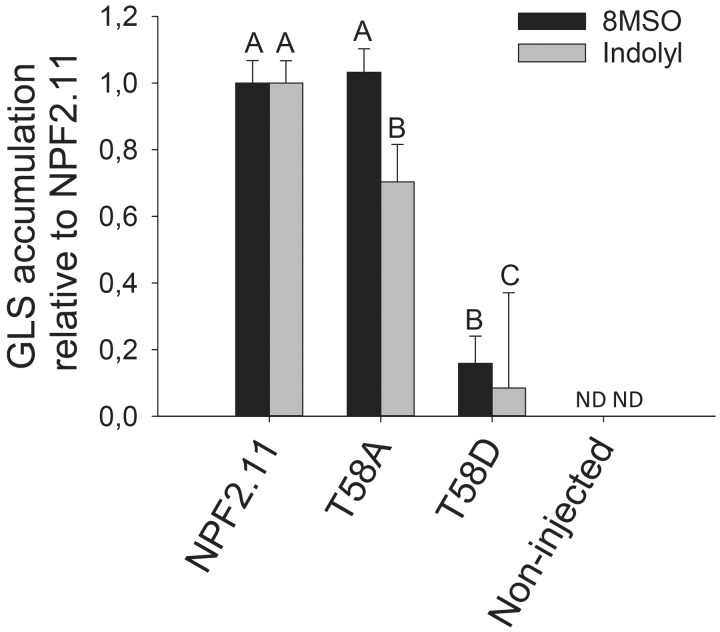

Is substrate specificity affected in the charge mutant T58D?

To investigate if the ability of T58D mutants to transport different classes of GLS was affected to the same extent, we measured the transport activity of NPF2.11-expresing, T58D-expressing and non-injected oocytes exposed to GLS isolated from an A. thaliana Ler accession that primarily contain long-chained, aliphatic 8-methylsulfinyloctylglucosinolate (8MSO) and indolyl GLS [sum of indol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate (I3M); 4-methoxy-3-indolylmethylglucosinolate (4MO-I3M) and 1-methoxy-3-indolylmethylglucosinolate (1MO-I3M)]. Uptake of 8MSO and indole GLS was as drastically reduced in oocytes expressing T58D (Fig. 7) compared with oocytes expressing NPF2.11, as was observed for 4MTB (Fig. 3A). This showed that the reduced transport activity observed for T58D was not substrate specific and was independent of side chain structure of the GLS.

Fig. 7.

Uptake of long-chain aliphatic 8MSO and indolyl GLS. NPF2.11 and T58D were expressed separately in 15 Xenopus oocytes, and transport activity was measured in the presence of 134 µM 8MSO, 31 µM I3M, 10 µM 4MO-I3M and 37 µM 1MO-I3M for 1 h at pH 5. Accumulated 8MSO and indolyl GLS were quantified by LC-MS in 3 × 5 oocytes for each gene. Groups are determined by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001) vs. NPF2.11. Error bars: SD, n = 3. ND = below the detection limit.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the E1X1X2E2K variant of the E1X1X2E2R motif in the GLS transporter NPF2.11 with special focus on the uncharacterized X1 and X2 residues that are conserved as uncharged residues within the Arabidopsis NPF.

The E57T58F59E60K61 motif is essential for active transport

NPF2.11 was previously characterized as a H+/GLS symporter that utilizes the ΔµH+ between the plant apoplast (pH 5.5) and cytoplasm (pH 7.4) to drive the import of GLS (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012). When we tested the ability of NPF2.11 to overaccumulate 4MTB in Xenopus oocytes (i.e. to a concentration above the concentration in the assay medium), a several fold overaccumulation of 4MTB relative to the assay medium was observed. For NPF2.11, the arginine residue in the canonical E1X1X2E2R motif is changed to a lysine, i.e. E57T58F59E60K61. Approximately 30% of Arabidopsis NPFs contain the E1X1X2E2K motif, whereas the remaining members contain the canonical E1X1X2E2R motif. The arginine to lysine substitution is considered a conservative substitution but may influence the transport properties as lysine only has one amino group whereas arginine has a guanidium group capable of forming a greater number of hydrogen bonds (Barnes 2007). Our finding—that NPF2.11 overaccumulate GLS against its concentration gradient—is the first experimental evidence that a transporter encoding the atypical E1X1X2E2K motif can overaccumulate substrate relative to the concentration in the assay medium.

Mutational studies of the E1X1X2E2R motif in the bacterial PepTSt suggested an important role for the E1X1X2E2R motif in proton coupling (Solcan et al. 2012). In addition, the E1X1X2E2R motif has been suggested to translocate a single proton per transport cycle, with both E1 and E2 as potential proton acceptors (Doki et al. 2013). The negative currents elicited by NPF2.11 when exposed to the negatively charged organic GLS anion indicate an influx of positive charge through NPF2.11 and hence a H+ to GLS stoichiometry of nH+ > nGLS (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012). The lack of 4MTB-induced currents combined with residual 4MTB uptake in the E57A, E60A and K61A mutants suggests non-electrogenic transport of GLS. This supports a role for the charged residues in the E57T58F59E60K61 motif in proton translocation across the membrane and thus that the E1X1X2E2K motif plays an important role in proton coupling. This is further supported by the inability of the E57A, E60A and K61A mutants to overaccumulate 4MTB relative to the concentration in the assay medium (only residual uptake remained).

Neutral residues in the E57T58F59E60K61 motif are essential for transport activity

No studies, to date, have investigated the role of the non-conserved X positions in the E1X1X2E2[K/R] motif. The conservation of neutral residues at X1 and X2 across kingdoms (Fig. 2) indicates a constraint enforced on these two positions. The E1X1X2E2R motif is situated in the middle of an α-helix in transmembrane domain 1 (TMD1) (Fig. 1C) at an apparent intersection with two other α-helices, and it is possible that introduction of charged amino acids at positions Thr58 and Phe59 causes protein rearrangements that would render the transport protein non-functional. This hypothesis is supported by abolished transport in mutants with a negative (aspartate) or positive (arginine) residue at position X2 and in mutants with a positive charge at position X1.

Introduction of leucine—a non-charged but less bulky amino acid—instead of phenylalanine at the X2 position also severely reduced transport activity (Fig. 4A). This was surprising as leucine occurs at the X2 position in three other experimentally tested NPF members (AIT1, NRT1.7 and NRT1.6) and also in three uncharacterized NPF members (Fig. 2). Thus, at the X2 position, functional NPF2.11 does not tolerate charged amino acids and appears to require the large side chain of phenylalanine. In contrast, reducing the size of the amino acid side chain at the X1 position did not affect transport activity, as shown by the wild-type transport properties of the T58A mutant (Fig. 4). Thus, at the X1 position positive charges are not tolerated whereas structural constraints with regards to the amino acid side chain appear less stringent. As a consequence, we suggest that the two X positions in the E1X1X2E2K motif are functionally distinct.

It appears that the T58D mutant is capable of actively accumulating 4MTB against a concentration gradient but at severely reduced rates and via a seemingly non-electrogenic transport process. Crystallization of PepTSt in the inward open conformation showed that the E2 and R residues (of the E1X1X2E2R motif) form a salt bridge in close proximity to the E1 residue. When mutating PepTSt-E2 and -R residues to glutamine (mimicking a protonated glutamate), the mutants lost the ability to accumulate substrate in proton-driven uptake experiments albeit that counterflow activity was retained (Solcan et al. 2012). This suggests that formation and breakage of this salt bridge (prior to and upon protonation) is involved in the proton-coupling mechanism of the E1X1X2E2R motif. We hypothesize that introduction of a negative charge at the X1 position creates an alternative salt bridge acceptor for Lys61 that interferes with proper proton coupling via the E57T58F59E60K61 motif. Similarly, the positively charged arginine residue introduced at the X1 position could interact with E57 or E60 and thereby hinder proton coupling.

In summary, our data indicate two constraints on the physicochemical properties of the amino acids at position X1 and X2 in the canonical E1X1X2E2[K/R] motif. One clear constraint is the conservation of both residues as neutral amino acids probably to avoid interference with the proton-coupling mechanism, which involves salt bridge formation between the negative and positive residues in the motif. In addition, it appears that a more complex structural constraint is imposed on the X2 position, which remains to be elucidated.

Materials and Methods

Construction of NPF2.11-E1X1X2E2K mutants

Site-directed mutagenesis of NPF2.11 was performed using USER™ Fusion (Nour-Eldin et al. 2006, Geu-Flores et al. 2007). Wild-type and mutated coding sequences were cloned into an oocyte expression vector harboring a C-terminal yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fluorophore or HA-tag. The generated mutants were named: NPF2.11::YFP(NPF2.11), NPF2.11-T58A::YFP(T58A), NPF2.11-T58D::YFP(T58D), NPF2.11-T58R::HA(T58R), NPF2.11-F59D::HA(F59D), NPF2.11-F59R::HA(F59R), NPF2.11-F59L::HA(F59L), NPF2.11-E57A::HA(E57A), NPF2.11-E60A::HA(E60A) and NPF2.11-K61A::HA (K61A).

The USER primers for epitope tagging of wild-type and mutant transporters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

USER primers for epitope tagging of wild-type and mutant transporters

| Primer | Name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| NPF2.11 HA-tagged mutants | ||

| 1 | NPF2.11 FW1 | GGCTTAAUATGGAGAGAAAGCCTCTTGAAC |

| 2.1 | NPF2.11 T58 FW (T→R) | ATTATTGGAAAUGAGAGGTTTGAGAAGCTTGGGATC |

| 2.2 | NPF2.11 F59 FW (F→D) | ATTATTGGAAAUGAGACAGACGAGAAGCTTGGGATC |

| 2.3 | NPF2.11 F59 FW (F→R) | ATTATTGGAAAUGAGACAAGGGAGAAGCTTGGGATC |

| 2.4 | NPF2.11 E57 FW (E→A) | ATTATTGGAAAUGCAACATTTGAGAAGCTTGGGATC |

| 2.5 | NPF2.11 E60 FW (E→A) | ATTATTGGAAAUGAGACATTTGCAAAGCTTGGGATC |

| 2.6 | NPF2.11 K61 FW (K→A) | ATTATTGGAAAUGAGACATTTGAGGCACTTGGGATC |

| 2.7 | NPF2.11 K61 FW (K→D) | ATTATTGGAAAUGAGACATTTGAGGACCTTGGGATC |

| 3 | T58 RV_1 (X→R/D/A) | ATTTCCAATAAUAAAGGGCATGACTTTCCAGCCTC |

| 4 | NPF2.11 RV- HA | GGTTTAAUTCAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAGGCAACGTTCTTGTCTTG |

| NPF2.11 YFP-tagged mutant | ||

| 1 | NPF2.11 FW1 | GGCTTAAUATGGAGAGAAAGCCTCTTGAAC |

| 2 | NPF2.11 T58 FW (T→D) | ATTATTGGAAAUGAGGACTTTGAGAAGCTTGGGATC |

| 3 | T58 RV_1 (T→D) | ATTTCCAATAAUAAAGGGCATGACTTTCCAGCCTC |

| 5 | NPF2.11 no stop RV2 | AGGCTGAGGUTTAATCCGGCAACGTTCTTGTCTTGCTGTTTG |

Oocyte preparation and cRNA injection

Xenopus oocytes (stages V–VI) were prepared as previously described (Carpaneto et al. 2005) or purchased as defolliculated Xenopus oocytes (stages V–VI) from Ecocyte Biosciences. Injection of 50 nl of cRNA (500 ng µl–1) into Xenopus oocytes was done using a Drummond NANOJECT II (Drummond Scientific Company). Oocytes were incubated for 3 d at 17°C in Kulori medium (90 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES) pH 7.4 prior to assaying.

Glucosinolate uptake/export assays

4MTB was obtained from C2 Bioengineering (Denmark), http://www.glucosinolates.com/. Xenopus uptake assays were carried out as described previously (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012). GLS export assays were carried out by injecting 50 nl of a 20 mM 4MTB solution per oocyte followed by transfer of injected oocytes to a standard Kulori medium pH 5. After 1 h, oocytes were removed and treated in the same manner as oocytes for uptake assays. For substrate specificity assays, an extract of leaf GLS from the A. thaliana Ler ecotype was used as a substrate for Xenopus oocyte uptake assays with NPF2.11 and T58D expressed in oocytes. Arabidopsis thaliana Ler primarily contains the long-chained aliphatic GLS 8MSO and the indolyl GLS I3M, 1MO-I3M and 4MO-I3M (Kliebenstein et al. 2001).

Calculation of oocyte volume

The oocyte concentration of 4MTB was calculated based on an estimated oocyte water content of approximately 70% (de Laat et al. 1974) and a maximal oocyte diameter of 1.5 mm. Based on this, the oocyte cytosolic volume was calculated to be 1 µl.

Glucosinolate analysis of Xenopus oocytes by LC-MS

ESI-LC-MS analysis of GLS from Xenopus uptake assays was performed as described previously (Nour-Eldin et al. 2012).

Electrophysiological measurements and data analysis

All measurements were performed with a TEVC system composed of an NPI TEC-03X amplifier (NPI electronic GmbH) connected to a PC with pCLAMP10 software (Molecular Devices) via an Axon Digidata 1440a digitizer (Molecular Devices).

TEVC recordings were performed as follows. (i) An oocyte was placed in the recording chamber and perfused with a standard Kulori-based solution (90 mM Na-gluconate, 1 mM K-gluconate, 1 mM Ca-gluconate2, 1 mM Mg-gluconate2, 1 mM LaCl3 and 10 mM MES pH 5). (ii) The oocyte was impaled by current and potential electrodes at a 45° angle and allowed to heal and equilibrate until the membrane potential was stable. (iii) The amplifier was switched to voltage clamp at –60 mV and the oocyte was allowed to establish a stable baseline, and currents in the absence of GLS substrate were measured in the voltage range between –30 and –170 mV in 10 mV decrements. (iv) When the baseline was stable, a standard Kulori-based solution with GLS substrate was perfused over the oocyte and currents were recorded in the voltage range between –30 and –170 mV in 10 mV decrements. TEVC data were extracted from pCLAMP10 software as a Microsoft Excel-compatible worksheet and analyzed in Excel. GLS-induced currents were calculated by subtracting currents before addition of GLS substrate from currents after addition of GLS substrate. SigmaPlot version 12.3 (Systat software) was used for statistical analysis and data plotting. Visualization and curve fitting to the Michaelis–Menten equation (Equation 1) to calculate the apparent Km value was done using SigmaPlot version 12.3 (Systat software).

| (1) |

Michaelis–Menten equation: I is the current, and Imax is the maximal current achieved by the transporter at saturating concentrations of 4MTB.

Xenopus oocyte protein extraction

Membrane and soluble proteins were isolated from Xenopus oocytes expressing wild-type or mutated NPF2.11 by the following protocol: one oocyte was homogenized in 100 µl of homogenization medium [20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7,6, 0.1 M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), buffer described in Galili et al. (1995)] and left on ice for 20 min. The homogenate was then cleared by centrifugation for 2 min at 10,000×g. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and 25 µl of 5× SDS sample buffer was added (60 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue).

Western blot

Samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. For detection of YFP-tagged proteins, we used a polyclonal rabbit-anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (Invitrogen A11122). For endogenous actin detection, we used polyclonal rabbit-anti-β-actin antibody (abcam-ab8227).

Western blot development

SuperSignal West Pico was used as chemiluminescent substrate and chemiluminescence was measured using a UVP autochemi system (UVP Bioimaging Systems).

Relative quantification of Western blot bands

Western blots were developed and analyzed by the standard ‘gel analysis’ tool in ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). To achieve a relative quantification, we compared the intensity of endogenous actin bands with the intensity of heterologously expressed transporter.

Oocyte fixation and bioimaging

Oocytes expressing NPF2.11::YFP and T58D:YFP were fixed in the manner described by Sayers et al. (1997). Briefly, oocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Oocytes were then sliced in two and mounted on a glass slide for bio imaging by confocal scanning microscopy using a SPX5-X Point-scanning Confocal from Leica Microsystems.

Sequence alignment

Aligned bacterial, fungal, worm, animal and plant POT/PTR transporters were previously described (Daniel et al. 2006, Newstead et al. 2011, Solcan et al. 2012, Doki et al. 2013, Guettou et al. 2013). All sequences were retrieved from NCBI or TAIR and aligned using CLC genomic workbench and ClustalW. The EXXE[K/R] motif was identified and all sequences were trimmed to show only the five amino acids of the EXXE[K/R] motif.

Homology modeling

NPF2.11 sequences were submitted to the SWISS-MODELS server and the highest scoring templates was used to generate homology models (swissmodel.expasy.org/) (Biasini et al. 2014). NPF2.11 was modeled on the NRT1.1 structure (PDB: 4OH3) (Sun et al. 2014). PDBsum was used to calculate Ramachandran Plot statistics where NPF2.11 had 1% of residues in disallowed regions (de Beer et al. 2014). Pymol was used for visualization of homology models and preparation of illustration.

Funding

This study was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation [grant No. DNRF99 to M.E.J., H.N.-E. and B.A.H.]. OM was supported by the Danish Council for Independant Research (Sapere aude grant 10-097670).

Acknowledgements

Frederikke Gro Malinovsky is acknowledged for Arabidopsis thaliana LER glucosinolate extraction mix. We also thank Nanna MacAulay and technicians Charlotte Goos Iversen and Catia Correa Goncalves Andersen (The Panum Institute, Copenhagen University) for providing X. laevis oocytes. All bio-imaging was done at the Center for Bio imaging facilities (CAB) Denmark.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GLS

glucosinolates

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- I3M

indol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate

- 1MO-I3M

1-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate

- 4MO-I3M

4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethyl glucosinolate

- 8MSO

8-methylsulfinyloctylglucosinolate

- 4MTB

4-methylsulfinylbutyl glucosinolate

- NPF

NRT1/PTR family

- POT/PTR

proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter

- TEVC

two-electrode voltage clamp

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Almagro A., Lin S.H., Tsay Y.F. (2008) Characterization of the Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.6 reveals a role of nitrate in early embryo development. Plant Cell 20: 3289–3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M.R. (2007) Bioinformatics for Geneticists: A Bioinformatics Primer for the Analysis of Genetic Data. Wiley, Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Biasini M., Bienert S., Waterhouse A., Arnold K., Studer G., Schmidt T., Kiefer F., Cassarino T.G., Bertoni M., Bordoli L., Schwede T. (2014) SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpaneto A., Geiger D., Bamberg E., Sauer N., Fromm J., Hedrich R. (2005) Phloem-localized, proton-coupled sucrose carrier ZmSUT1 mediates sucrose efflux under the control of the sucrose gradient and the proton motive force. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 21437–21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C.C., Lin C.S., Hsia A.P., Su R.C., Lin H.L., Tsay Y.F. (2004) Mutation of a nitrate transporter, AtNRT1:4, results in a reduced petiole nitrate content and altered leaf development. Plant Cell Physiol. 45: 1139–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel H., Spanier B., Kottra G., Weitz D. (2006) From bacteria to man: archaic proton-dependent peptide transporters at work. Physiology 21: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beer T.A., Berka K., Thornton J.M., Laskowski R.A. (2014) PDBsum additions. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: D292–D296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat S.W., Buwalda R.J., Habets A.M. (1974) Intracellular ionic distribution, cell membrane permeability and membrane potential of the Xenopus egg during first cleavage. Exp. Cell Res. 89: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich D., Hammes U., Thor K., Suter-Grotemeyer M., Fluckiger R., Slusarenko A.J., et al. (2004) AtPTR1, a plasma membrane peptide transporter expressed during seed germination and in vascular tissue of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 40: 488–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doki S., Kato H.E., Solcan N., Iwaki M., Koyama M., Hattori M., et al. (2013) Structural basis for dynamic mechanism of proton-coupled symport by the peptide transporter POT. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110: 11343–11348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S.C., Lin C.S., Hsu P.K., Lin S.H., Tsay Y.F. (2009) The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.7, expressed in phloem, is responsible for source-to-sink remobilization of nitrate. Plant Cell 21: 2750–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest L.R., Kramer R., Ziegler C. (2011) The structural basis of secondary active transport mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807: 167–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili G., Altschuler Y., Ceriotti A. (1995) Synthesis of plant proteins in heterologous systems: Xenopus laevis oocytes. Methods Cell Biol. 59: 497–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geu-Flores F., Nour-Eldin H.H., Nielsen M.T., Halkier B.A. (2007) USER fusion: a rapid and efficient method for simultaneous fusion and cloning of multiple PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guettou F., Quistgaard E.M., Tresaugues L., Moberg P., Jegerschold C., Zhu L., et al. (2013) Structural insights into substrate recognition in proton-dependent oligopeptide transporters. EMBO Rep. 14: 804–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P.K., Tsay Y.F. (2013) Two phloem nitrate transporters, NRT1.11 and NRT1.12, are important for redistributing xylem-borne nitrate to enhance plant growth. Plant Physiol. 163: 844–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno Y., Hanada A., Chiba Y., Ichikawa T., Nakazawa M., Matsui M., et al. (2012) Identification of an abscisic acid transporter by functional screening using the receptor complex as a sensor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109: 9653–9658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein D.J., Kroymann J., Brown P., Figuth A., Pedersen D., Gershenzon J., et al. (2001) Genetic control of natural variation in Arabidopsis glucosinolate accumulation. Plant Physiol. 126: 811–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova N.Y., Thor K., Gubler A., Meier S., Dietrich D., Weichert A., Suter G.M., Tegeder M., Rentsch D. (2008) AtPTR1 and AtPTR5 transport dipeptides in planta. Plant Physiol. 148: 856–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouk G., Lacombe B., Bielach A., Perrine-Walker F., Malinska K., Mounier E., et al. (2010) Nitrate-regulated auxin transport by NRT1.1 defines a mechanism for nutrient sensing in plants. Dev. Cell 18: 927–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law C.J., Maloney P.C., Wang D.N. (2008) Ins and outs of major facilitator superfamily antiporters. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62: 289–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leran S., Varala K., Boyer J.C., Chiurazzi M., Crawford N., Daniel-Vedele F., et al. (2014) A unified nomenclature of NITRATE TRANSPORTER 1/PEPTIDE TRANSPORTER family members in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 19: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.Y., Fu Y.L., Pike S.M., Bao J., Tian W., Zhang Y., et al. (2010) The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.8 functions in nitrate removal from the xylem sap and mediates cadmium tolerance. Plant Cell 22: 1633–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.H., Kuo H.F., Canivenc G., Lin C.S., Lepetit M., Hsu P.K., et al. (2008) Mutation of the Arabidopsis NRT1.5 nitrate transporter causes defective root-to-shoot nitrate transport. Plant Cell 20: 2514–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newstead S. (2015) Molecular insights into proton coupled peptide transport in the PTR family of oligopeptide transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1850: 488–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newstead S., Drew D., Cameron A.D., Postis V.L., Xia X., Fowler P.W., et al. (2011) Crystal structure of a prokaryotic homologue of the mammalian oligopeptide–proton symporters, PepT1 and PepT2. EMBO J. 30: 417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour-Eldin H.H., Andersen T.G., Burow M., Madsen S.R., Jorgensen M.E., Olsen C.E., et al. (2012) NRT/PTR transporters are essential for translocation of glucosinolate defence compounds to seeds. Nature 488: 531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour-Eldin H.H., Hansen B.G., Norholm M.H., Jensen J.K., Halkier B.A. (2006) Advancing uracil-excision based cloning towards an ideal technique for cloning PCR fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers L.G., Miyawaki A., Muto A., Takeshita H., Yamamoto A., Michikawa T., et al. (1997) Intracellular targeting and homotetramer formation of a truncated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor–green fluorescent protein chimera in Xenopus laevis oocytes: evidence for the involvement of the transmembrane spanning domain in endoplasmic reticulum targeting and homotetramer complex formation. Biochem. J. 323: 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segonzac C., Boyer J.C., Ipotesi E., Szponarski W., Tillard P., Touraine B., et al. (2007) Nitrate efflux at the root plasma membrane: identification of an Arabidopsis excretion transporter. Plant Cell 19: 3760–3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solcan N., Kwok J., Fowler P.W., Cameron A.D., Drew D., Iwata S., et al. (2012) Alternating access mechanism in the POT family of oligopeptide transporters. EMBO J. 31: 3411–3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Bankston J.R., Payandeh J., Hinds T.R., Zagotta W.N., Zheng N. (2014) Crystal structure of the plant dual-affinity nitrate transporter NRT1.1. Nature 507: 73–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay Y.F., Schroeder J.I., Feldmann K.A., Crawford N.M. (1993) The herbicide sensitivity gene CHL1 of Arabidopsis encodes a nitrate-inducible nitrate transporter. Cell 72: 705–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.Y., Tsay Y.F. (2011) Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.9 is important in phloem nitrate transport. Plant Cell 23: 1945–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichert A., Brinkmann C., Komarova N.Y., Dietrich D., Thor K., Meier S., et al. (2012) AtPTR4 and AtPTR6 are differentially expressed, tonoplast-localized members of the peptide transporter/nitrate transporter 1 (PTR/NRT1) family. Planta 235: 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]