Abstract

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is known to play several important roles in vascular development, although the molecular mechanisms behind these remain largely unknown. RECK, a tumor suppressor downregulated in a wide variety of cancers, encodes a membrane-anchored matrix-metalloproteinase-regulator. Mice lacking functional Reck die in utero, demonstrating its importance for mammalian embryogenesis; however, the underlying causes of mid-gestation lethality remain unclear. Using Reck conditional knockout mice, we have now demonstrated that the lack of Reck in vascular mural cells is largely responsible for mid-gestation lethality. Experiments using cultured aortic explants further revealed that Reck is essential for at least two events in sprouting angiogenesis; (1) correct association of mural and endothelial tip cells to the microvessels and (2) maintenance of fibronectin matrix surrounding the vessels. These findings demonstrate the importance of appropriate cell-cell interactions and ECM maintenance for angiogenesis and the involvement of Reck as a critical regulator of these events.

Correct vascular development is crucial for all aspects of tissue growth and physiology in vertebrates. In mammals, two families of cytokines; vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) and angiopoietins, are known to play a lead role in angiogenesis1,2,3,4,5. Early events during sprouting angiogenesis involve specialization of activated endothelial cells into two distinct subtypes: namely, tip and stalk cells. VEGF stimulates the expression of tip cell markers, including Flk1 and Notch-ligands of which the Notch-ligands stimulate Notch-signaling in adjacent cells to suppress their tip cell phenotype (lateral inhibition) and induce the phenotype of lumen-forming stalk cells6. For vascular stabilization, endothelial tubes need to recruit, and be tightly associated with, mural cells (i. e., vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes), whilst platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) serves as a key attractant in this process7. This cell-cell interaction triggers the perivascular deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as fibronectin (FN) and vascular basement membrane (vBM) to promote vessel maturation and stabilization8,9. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are also known to play major roles in the ECM-remodeling associated with angiogenesis10,11, although how this process is regulated remains to be elucidated.

RECK, conserved as a single gene from insects to primates, encodes a membrane-anchored regulator of multiple metalloproteinases, including several members of the MMP family12,13,14,15,16,17,18. In mammalian cells, RECK expression is downregulated by various external stimuli, such as growth factors, low cell density, and low oxygen19,20,21. RECK expression is also downregulated frequently in cancer cells, and restoration of RECK expression in such cells results in suppression of tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis in xenograft models14,17. Recent evidence indicates that several oncogenic microRNAs target RECK mRNA20,22,23,24,25,26, strengthening the notion that RECK is a tumor suppressor that is downregulated via various mechanisms during carcinogenesis.

Previous studies have also revealed the critical functions of Reck in mammalian development. Mice lacking Reck-expression die in utero around embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5), exhibiting reduced tissue integrity, arrested vasculogenesis13, and precocious neuronal differentiation13,16. A mouse mutant with reduced Reck-expression (ReckLow/∆, see below) demonstrates defects in limb patterning; a phenotype that can be explained by impaired Wnt7a-signalling due to tissue damage in limb-bud mesenchyme and overlaying dorsal epithelium21. In some rapidly proliferating tissues, such as embryos and uterine implantation chambers, Reck expression is abundant in both vascular endothelial cells and mural cells27. Dilated vessels with abnormal luminal shapes can be observed in these tissues in mice with reduced Reck expression. Abundant Reck-expression has also been found in fibroblastic cells associated with bifurcating vessels, leading to the speculation that Reck may play a role in non-sprouting angiogenesis (e.g., intussusception and pruning)27.

In the present study, we dissected the roles for Reck in different vascular cell types during angiogenesis by using multiple lines of newly developed Reck mutant mice. We also employed aortic ring assay (ARA)28,29 to assess the ability of aortic tissue explants to form small vessels (microvessels) in vitro. We found that selective inactivation of Reck in vascular mural cells caused embryonic death around E10.5 with vascular defects, suggesting that the mid-gestation lethality of Reck-null mice can be attributed to the absence of Reck in mural cells. In addition, we unexpectedly found that impaired Reck function leads to excessive sprouting of unstable microvessels in vitro, raising the possibility that the abnormal, dilated vessels found in Reck-deficient mice may arise by lateral fusion of unstable vessels rather than, or in addition to, abortive intussusception.

Results

Cell type-selective inactivation of Reck in vivo

The engineered Reck alleles in mice used in this study are listed in Fig. 1a: (1) Reck-, the original null-allele13, (2) ReckCrER, expressing the tamoxifen-regulatable Cre recombinase CreERT2 from the Reck locus (Matsuzaki et al. in preparation); (3) ReckE1fx, containing two lox-P sites flanking exon-1; (4) Reck∆, a novel null-allele lacking proximal promoter plus exon-1; and (5) ReckLow, a hypomorphic allele expressing Reck at ~50% of the wild type (wt) level21. In addition, we utilized two Cre transgenic lines, Sm22-Cre30 and Tie2-Cre31, to induce loxP-recombination selectively in mural and endothelial cells, respectively.

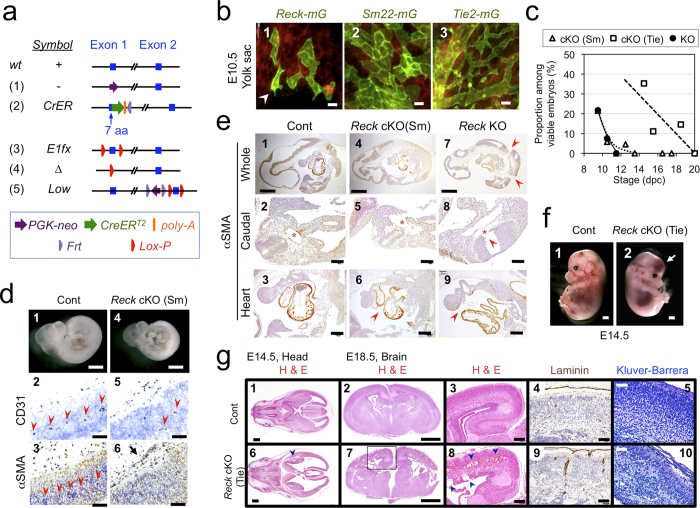

Figure 1. Cell type-selective inactivation of Reck in vivo using Sm22-Cre or Tie2-Cre mice.

(a) Reck alleles used in this study. (b) Cells that expressed Reck (1), Sm22 (2, mural cells), or Tie2 (3, endothelial cells) emitted green fluorescence in the yolk sac of E10.5 embryos. For Reck, a pregnant mouse was injected with tamoxifen at 8.5 dpc. Arrowhead indicates a cell with ambiguous morphology. (c) Viability of global Reck KO mice (Reck−/−, filled circles with solid line) or tissue-selective Reck knockouts, Reck cKO (Sm) [ReckE1fx/∆; Sm22-Cre, triangles] or Reck cKO (Tie) [ReckE1fx/∆; Tie2-Cre, square]. Expected frequency was 25% in all cases. (d) Morphology of control (ReckE1fx/∆) and Reck cKO (Sm) mice at E10.5. Whole embryo (panels 1, 4) and the dorsal, peri-neural area of serial sagittal sections, immunostained for CD31 (panels 2, 5) or αSMA (panels 3, 6), are shown. Brown signals indicate immunoreactivity. Arrow indicates an abnormal peri-neural vessel. Arrowheads highlight CD31-positive small vessels within the neural tube. (e) Distribution of αSMA-immunoreactivity in the sagittal sections of control, Reck cKO (Sm), and Reck KO mice at E10.5. Whole section (top row), caudal area containing a cross-sectional view of the neural tube and dorsal aorta (second row), and the heart (third row) are shown. Arrowheads show broken sites in panels 7, 8 and missing pericardial membrane in panels 6, 9. Asterisks highlight dorsal aorta. (f) Gross morphology of the control (ReckE1fx/∆) and Reck cKO (Tie) mice at E14.5. Arrow indicates intra-cranial hemorrhage. (g) Brain morphology in sections of control (upper panels) or Reck cKO (Tie) mice (lower panels) at E14.5 (panels 1, 2, 6, 7) or E18.5 (3–5, 8–10) that were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (panels 1–3, 6–8), anti-laminin (panels 4, 9), or Kluver-Barrera (panels 5, 10) staining. Arrowheads indicate intra-cranial hemorrhage. Scale bar: (b) 20 μm; (d) 1 mm (1, 4), 50 μm (other panels); (e) 1 mm (1, 4, 7), 100 μm (2, 5, 8), 200 μm (3, 6, 9); (f) 1 mm; (g) 1 mm (1, 2, 6, 7), 200 μm (3, 8), 100 μm (4, 9), 50 μm (5, 10).

Visualization of Reck-positive cells in the yolk sac at embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5), using mice carrying the ReckCrER allele together with the mTmG reporter system32, revealed that the majority of Reck-mG cells (green; Fig. 1b-1) exhibit cobble stone-like alignment resembling that of Sm22-mG vascular mural cells (green, Fig. 1b-2). This phenotype was widespread, rather than the dendritic pattern of Tie2-mG vascular endothelial cells (green, Fig. 1b-3), although some cells with ambiguous morphology were also observed (e.g, Fig. 1b-1, arrowhead).

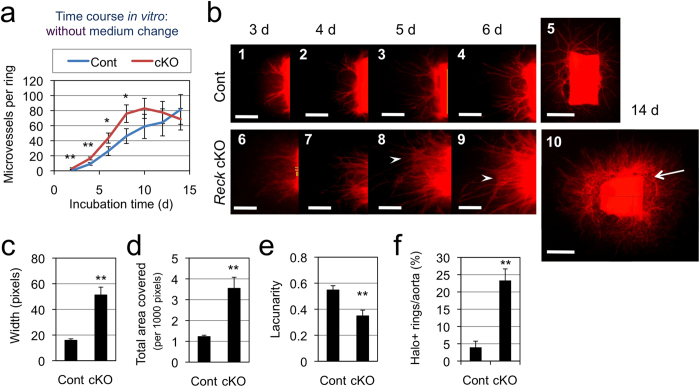

Figure 2. Effects of Reck-deficiency on microvessel formation in ARA.

(a) Time course of microvessel formation (number per ring). Aortic rings from 5-weeks old control (Reck+/CrER; mTmG, blue line, n = 9) or Reck cKO (ReckE1fx/CrER; mTmG, red line, n = 4) mice were subjected to ARA (no medium change), and the number of microvessels was counted every other day from day 2 to 14. (b) Fluorescent micrographs of a control (panels 1–5) or Reck cKO (panels 6–10) ring after incubation for indicated period of time in ARA without medium changes. Arrow indicates peri-aortic halo, and arrowheads highlight aggregating microvessels. Scale bar: 1 mm (5, 10), 0.5 mm (other panels). (c) Relative width of microvessels measured using ImageJ on high magnification images. Summary of 6 independent experiments (n = 36 rings for Cont and 30 rings for Reck cKO in total). (d, e) Parameters measured using AngioTool44. Summary of 8 independent experiments for Cont (46 rings) and 7 experiments for Reck cKO (43 rings). (f) Frequency of rings exhibiting peri-aortic halo. Summary of 6 independent experiments for Cont (78 rings) and 3 independent experiments for Reck cKO (30 rings).

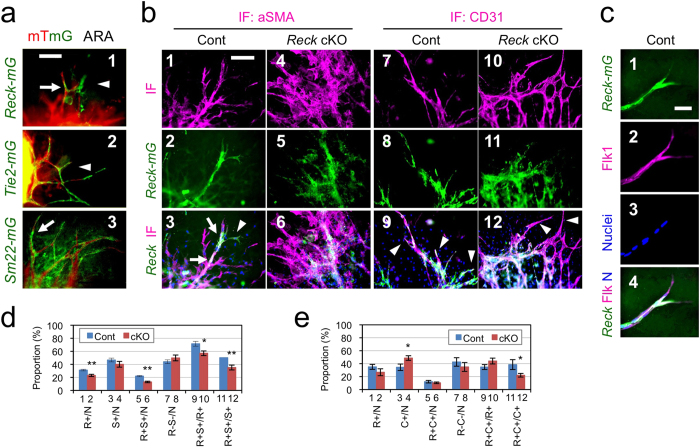

Figure 3. Identity and behavior of Reck-mG cells in ARA.

(a) Morphology and microvessel-association of Reck-mG (1), Tie2-mG (2), and Sm22-mG (3) cells (green) in ARA at day 8. (b) Effects of Reck-deficiency on the nature of, and relationship between, Reck-mG, endothelial, and mural cells. Aortic rings from the control (Reck+/CrER; mTmG) or Reck cKO (ReckE1fx/CrER; mTmG) mice were subjected to ARA and immunostained for αSMA (magenta in panels 1, 3, 4, 6) or CD31 (magenta in panels 7, 9, 10, 12) at day 11. Green signals represent Reck-mG cells. Reck-mG/αSMA double positive staining could be observed at microvessel stalks from control mice (white stain, arrow, panel 3). In control cultures, Reck-mG/CD31 double positive staining could be observed at microvessel tips (white stain, arrowheads, panel 9) and Reck-mG single positive staining found at microvessel stalks (green stain, panel 9). This was lost in Reck cKO mice as observed by the lack of Reck-mG/CD31 double positive at the microvessel tips (arrowheads, panel 12). (c) Flk1 immunoreactivity in a control microvessel. The control culture as in (b) was immunostained for a vascular tip-cell marker, Flk1/Vegfr2 (magenta in panel 2 and 4). (d) Frequency of various cells in Reck-mG/αSMA double labeling experiments as shown in (b), panels 1–6. (e)Frequency of various cells in Reck-mG/CD31 double labeling experiments as shown in (b), panels 7–12. N = total nuclei, R = Reck-mG, S = αSMA, C=CD31, “+” means “-positive”. Number of images analyzed: (d) Cont (n = 17), Reck cKO (n = 12). (e) Cont (n = 6), Reck cKO (n = 9). Bars 1–8 represent proportion among all cells. Bars 9 and10 represent proportion among Reck-mG cells. Bars 11 and 12 represent proportion among αSMA-positive cells (d) or CD31-positive cells (e). Aortic rings were prepared from at least 3 animals per group. Scale bar: (a, b) 100 μm, (c) 20 μm.

First, to assess the contribution of mural Reck to vascular development, Reck was inactivated using the Sm22-Cre driver mouse (Supplementary Fig. S1a,b). The resulting mutant mice, termed Reck cKO (Sm), were reminiscent of Reck−/− mice13,27 in that they died around E10.5 (Fig. 1c, triangles) with smaller body size (Fig. 1d-4), poor vascularization in the neural tube (Fig. 1d-5), and dilated perineural vasculature with peculiar luminal shape (Fig. 1d-6). As reported previously, Reck−/− embryos displayed reduced tissue integrity (Fig. 1e-7) with frequent breakage of the neural tube (e.g., Fig. 1e-8, arrowhead)2. Although Reck cKO (Sm) embryos were not as fragile (Fig. 1e-4), they shared some phenotypes with Reck−/− mice such as frequent breakage of dorsal aorta (Fig. 1e-5) and pericardial membrane (Fig. 1e-6). Hence, the mid-gestation lethality of Reck-null mice13 may largely be attributable to the Reck-deficiency in mural cells.

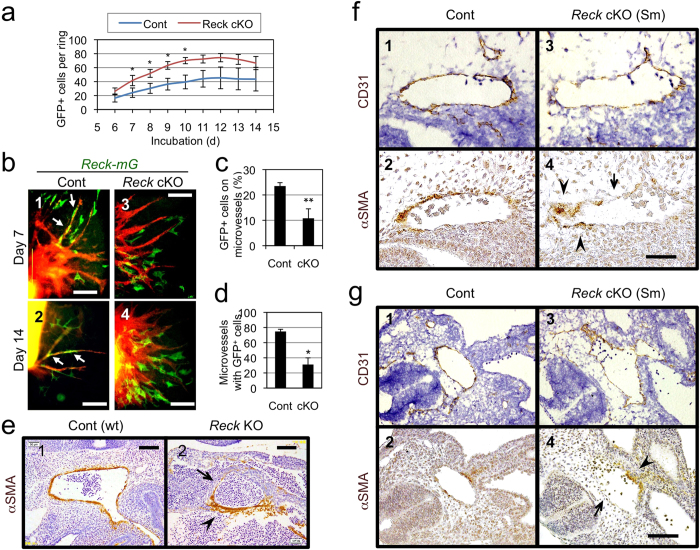

Figure 4. Effects of Reck on vessel-association of Reck-mG cells in ARA and mural cells in vivo.

(a) Time course for the number of Reck-mG cells in ARA. Aortic rings from the 5-weeks-old control (n = 10) or Reck cKO (n = 7) mice were subjected to ARA and all Reck-mG cells surrounding each ring (irrespective or their association with microvessels) were counted from day 6 to 14. (b) Distribution and morphology of Reck-mG cells (green) at day 7 and 14 in ARA. In control cultures, Reck-mG cells are tightly associated with microvessel stalks (arrows in panel 1 and 2) but this is impaired in Reck cKO (panel 3 and 4). (c) Frequency of Reck-mG cells tightly associated with microvessels at day 8. n = 3. (d) Frequency of microvessels with tightly associated Reck-mG cells at day 8. n = 3. (e–g) Effect of Reck-deficiency on the distribution of mural cells in vivo. (e) Sagittal section of wild type (Cont) or Reck−/− (Reck KO) mouse embryos at E10.5 immunostained for αSMA (brown). Micrographs focusing on large aorta are shown. (f,g) Sagittal sections of ReckE1fx/∆ mice (control; panels 1, 2) and Reck cKO (Sm) mice (panels 3, 4) at E10.5. Adjacent sections were immunostained for CD31 (with Hematoxylin counter-stain; panels 1, 3) and for αSMA (panels 2, 4), respectively. Micrographs focusing on large aortas in the middle (f) and caudal (g) part of the body are shown. In (e–g), arrowhead indicates an area of vessel wall abundant in mural cells, and arrow highlights an area where the mural cell layer is very thin or absent. Scale bar: (b) 200 μm (panel 2) and 50 μm (other panels), (e) 100 μm, (f) 50 μm, (g) 100 μm.

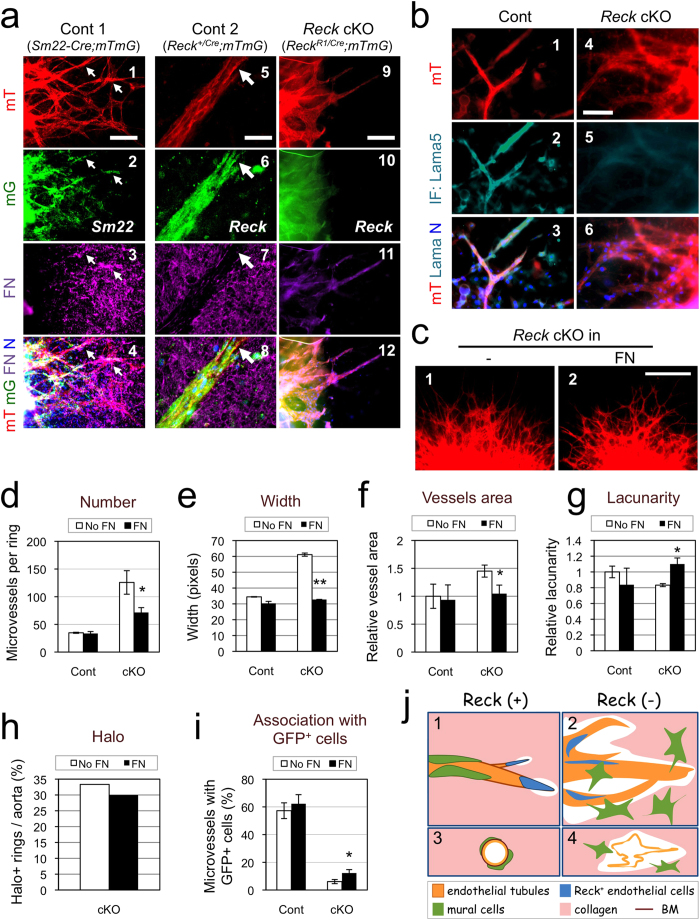

Figure 5. Functional relationship between Reck and FN in microvessel formation in ARA.

(a) Effects of Reck-deficiency on FN fibrils in ARA. Aortic rings from control 1 (Reck+/+; Sm22-Cre; mTmG), control 2 (Reck+/CrER; mTmG), and Reck cKO (ReckE1fx/CrER; mTmG) mice pretreated with tamoxifen were subjected to ARA and stained for FN (magenta, panels 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12) at day 10. Note that in the control samples, FN (magenta) signals are abundant around the extending sprouts (panels 3, 7), particularly accumulated in the areas where mT (red) and Sm22 (green) signals overlap (arrows in panels 1–4), but sparse near the tip of the sprouts (arrow in panels 5–8). Paucity of FN (magenta) signals in Reck cKO sample (panels 9–12) could also be observed. (b) Similar cultures stained for laminin α 5 (Lama5, turquoise). (c–i) Effects of exogenous FN on the phenotype of Reck cKO microvessels in ARA. ARAs were performed without or with addition of FN (1 μg/ml) in the gel. (c) Typical morphology of microvessels from Reck cKO aortic rings after incubation for 9 days in the absence (1) or presence (2) of exogenous FN. (d–i) Indicated parameters were measured as described in Fig. 2 a, c-f (d–h) and Fig. 4d (i) using micrographs (as shown in c) taken at day 10. Cont: n ≥ 14 rings (3 aortae); Reck cKO: n ≥ 43 rings (6 aortae). (j) A model consistent with our findings in vitro. When Reck is present (panels 1, 3), endothelial sprouting led by tip cells (blue) is appropriately regulated; tight association of mural cells (green) with endothelial tubules (orange) is promoted; and individual vessels are stabilised. When Reck is absent or reduced (panels 2, 4), endothelial sprouting and collagenolysis are activated; tip cells and mural cells localise inappropriately; and microvessels destabilise, permitting lateral fusion and ectopic anastomoses. Scale bar: (a) 20 μm in panels 5–8, 100 μm in others; (b) 50 μm; (c) 1 mm.

Next, to assess the contribution of endothelial Reck, Reck was inactivated using the Tie2-Cre mouse (Supplementary Fig. S1c,d). Although the mutant mice, termed Reck cKO (Tie), survived beyond E10.5, they died before birth (Fig. 1c, squares) and exhibited intra-cranial hemorrhage (Fig. 1f-2; Fig. 1g, panels 6–8) with severe abnormalities in vasculature and cytoarchitecture in their cerebral cortex (Fig. 1g, panels 7–10). Hence, Reck in Tie2-positive cells is indispensable for later-stage embryogenesis, particularly within the brain.

Effects of Reck-deficiency on microvessel formation

To understand the roles of Reck at the cellular level, ARAs28,29 were utilized, which allowed assessment of the ability of dorsal aorta tissue pieces (aortic rings) to form microvessels in vitro. Aortae from 5-weeks old, tamoxifen-induced Reck knockout (Reck cKO) and control (Cont) mice carrying the mTmG reporter were used. Under optimized conditions (Supplementary Figs S2 and S3a), control aortic rings showed a slow but steady increase in microvessel number over the time course observed (Fig. 2a, blue line), whereas Reck cKO samples showed an initial rapid increase (up to day 10) followed by a decline (from day 12) in the number of microvessels (Fig. 2a, red line). This decline was accompanied by aggregation and thickening of microvessels (Fig. 2b-8, 9, arrowheads; Supplementary Fig. S3b,c). Morphometry of fluorescent images (Fig. 2c-f and Supplementary Fig. S4) indicated that the Reck cKO microvessels were wider (Fig. 2c) and covered a broader area (Fig. 2d) with lower lacunarity (Fig. 2e). In addition, Reck cKO aortic rings were often accompanied by peri-aortic halos, indicating increased local lysis of collagen gel33 (Fig. 2b-10, arrow; Fig. 2f). Thus, Reck–deficiency leads to the formation of an excessive number of unstable microvessels in this assay.

Identity of Reck-mG cells

To determine how Reck-deficiency leads to such microvessel phenotypes, the nature of Reck-mG cells in ARA was examined. In control cultures, some Reck-mG cells localize at microvessel tips (Fig. 3a-1, arrowhead), whilst others are associated with microvessel stalks (Fig. 3a-1, arrow). The former look similar to the Tie2-mG or CD31-positive endothelial cells (Fig. 3a-2, arrowhead; Supplementary Fig. S5a, magenta) and the latter the Sm22-mG-positive mural cells (Fig. 3a-3, arrow; Supplementary Fig. S5a, green). Immunofluorescent staining for another mural marker, αSMA, often detected Reck-mG/αSMA double-positive (i.e., mural Reck-mG) cells surrounding microvessel stalks (Fig. 3b-3 and Supplementary Fig. S6-3, white signals as indicated by arrows); CD31-staining detected Reck-mG/CD31 double-positive (endothelial Reck-mG) cells near microvessel tips (Fig. 3b-9 and Supplementary Fig. S6-9, white signals as indicated by arrowheads) along with Reck-mG single-positive (non-endothelial Reck-mG) cells surrounding microvessel stalks (Fig. 3b-9 and Supplementary Fig. S6-9, green signals). Reck-mG cells found near microvessel tips were often positive for a vascular tip cell marker, Flk1 (Fig. 3c-2, magenta). These results, together with morphometric data (Fig. 3d, e), indicate that Reck-mG cells in control cultures contain both mural (ca. 70%; Fig. 3d, bar 9) and endothelial (ca. 30%; Fig. 3e, bar 9) populations.

Effects of Reck on the number and behaviors of Reck-mG cells

Reck-deficiency had multiple effects on Reck-mG cells. First, the number of Reck-mG cells surrounding an aortic ring was increased (Fig. 4a) whilst Ki67-staining revealed increased proliferation of both microvessel-associated and non-associated cells (Supplementary Fig. S5b and c, magenta). Second, the proportion of mural Reck-mG cells was decreased (Fig. 3d, bars 6, 12) whereas that of Reck-mG-negative endothelial cells was increased (Fig. 3e, bar 4). Third, endothelial Reck-mG cells were seldom found at microvessel tips in Reck cKO samples (Fig. 3b-12 and Supplementary Fig. S6-12, arrowheads; Supplementary Fig. S5d). Fourth, tight association of Reck-mG cells with microvessel stalks was somehow impaired (Figs. 4b-3 and -4; Fig. 4c, d); consistent to this finding in vitro, large aortae were frequently surrounded partially and unevenly by αSMA-positive mural cells that are not so tightly associated with a vessel as the control (Figs 4e-1) in sections of Reck−/− embryos at E10.5 (Figs 4e-2). Partial and uneven coverage of large aortae by αSMA-positive cells was also found in Reck cKO (Sm) embryos at E10.5 (Fig. 4f, g), suggesting a cell-autonomous function of Reck manifested in this phenotype. In addition, the irregularly spaced small vessels (CD31-positive) in the neural tube of Reck cKO (Sm) mice were seldom accompanied by αSMA-positive mural cells (Figs 1d-5 and 6). Taken together, these findings suggest that Reck is required to achieve adequate compositions of, and interactions between, vessel-forming cells.

Functional relationship between Reck and FN in microvessel formation

FN and its receptor are known to be protected by RECK18,34,35. In ARA with Reck-positive cells, abundant FN fibrils could be visualized by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 5a, panel 3 and 7), and prominent signals were found in the areas where mural (Sm22-mG) cells tightly associated with microvessels (Fig. 5a, panels 1–4, arrows). Near the tips of these microvessels, localized loss of FN fibrils were found near microvessel tips (Fig. 5a, panel 5–8, arrow). In Reck cKO cultures, signals for both FN (Fig. 5a-11) and laminin α 5 (Lama5), a component of vBM (Fig. 5b-5), were dampened and diffuse. When Reck cKO aortic rings were embedded in collagen gel supplemented with purified FN (Fig. 5c), some Reck cKO phenotypes, such as increased number, width, and aggregation of microvessels, increased area covered by microvessels, and decreased lacunarity of vascular network, were significantly suppressed (Fig. 5c-g) with increased perivascular FN- and Lama5-immunoreactivity (Supplementary Fig. S7a and b). Other Reck cKO phenotypes, such as peri-aortic halo and poor association of Reck-mG cells with microvessels, were not fully suppressed by FN supplementation (Fig. 5h, i). Hence, some Reck cKO phenotypes in ARA, such as excessive sprouting and destabilized microvessels, may be attributable to the reduced ambient FN in the absence of Reck.

Discussion

In this study, the importance of Reck in both mural and endothelial cells was documented in vivo and in vitro. Although selective inactivation of Reck in mural cells in vivo resulted in mid-gestation lethality and vascular defects reminiscent of Reck-null mice (Fig. 1c–e and ref. 2)Reck-inactivation in Tie2-positive cells also resulted in embryonic death, albeit at later stages with major impacts in the brain (Fig. 1c, f,g). In vitro, Reck-positive cells contribute to both mural and endothelial lineages (Fig. 3) whilst Reck-inactivation results in increased sprouting, decreased microvessel stability (Fig. 2) and altered composition (Fig. 3d–f) alongside a change in behavior that includes defective localization and reduced association (Figs 3b,4; Supplementary Fig. S5d) of vascular cells whose normal counterparts express Reck.

Senger, Stratman, and Davis have proposed that mural-endothelial interaction triggers perivascular FN-deposition and subsequent vBM-deposition required for vascular stability in vivo 8,9. Our data in vitro suggest that Reck plays a key role in this process by protecting FN from degradation (Supplementary Fig. S7c). The failure of FN to fully normalize the association of Reck-mG cells to the microvessels (Fig. 5i) fits with this model, (Supplementary Fig.S7c) which places the mural-endothelial interaction upstream of FN-deposition; raising a new question as to how Reck promotes this upstream event. Attenuated PDGF-receptor immunoreactivity found in Reck-deficient cells (Supplementary Fig. S8a and b) may be suggestive of its involvement in this failure, since PDGF is known to play a key role in pericyte-recruitment by endothelial cells 36 (Supplementary Fig. S8d-1).

The mechanism underlying the contribution of Reck-deficiency to the mislocalization of Reck-mG tip cells is presently unclear but several hypotheses can be envisaged. In Reck cKO culture, Flk1 signals were dampened and scarce in cells at the microvessel tips (Supplementary Fig. S5d, magenta), suggesting abortive tip-stalk specification. Reck-deficient mice exhibit precocious neuronal differentiation, and this has been explained by attenuated Notch-signaling in neural precursor cells, due to de-regulated Adam10 that clips off Notch-ligands from adjacent cells16. In the vascular system, Notch signaling is known to suppress the tip cell phenotype and to promote acquisition of the stalk cell phenotype6. Hence, an obvious model is that attenuated Notch-signaling in this system leads to ectopic expression of tip cell phenotype, which can explain the excessive sprouting found in Reck cKO rings in ARA. This model, however, predicts upregulation and/or ectopic expression of tip-cell markers (such as Flk1), but this was not the observed (Supplementary Fig. S5d). An alternative model involves direct Flk1-downregulation, for instance, by proteolytic cleavage that may scramble tip-stalk specification (Supplementary Fig. S8d-2). Another potential model is binding between VEGF and FN37 that somehow contributes to tip-stalk association or specification (Supplementary Fig. S8d-3), which fits with our finding that FN may suppress the mislocalization of tip cells found in Reck cKO samples to some extent (Supplementary Fig. S8c; Fig. 5i).

Likewise, multiple models can be proposed to explain the increased cell proliferation found in Reck cKO cultures. Since Notch-signaling is known to confer quiescence to the vessels6, reduced Notch-ligands may promote cell proliferation. Alternatively, as observed in colon cancer cells38, Reck-deficiency may promote cell cycle progression by upregulating Skp2, thereby downregulating the Cdk inhibitor p27. These issues need to be addressed in future studies.

We have previously speculated that dilated vessels found in Reck-deficient mice may result from impaired non-sprouting angiogenesis (i.e., intussusception)27. The present data, however, support an alternative model that dilated vessels could result from aggregation and lateral fusion of excessive, unstable microvessels (Fig. 5j-4). Our data also raise the interesting possibility that Reck may serve as a key regulator of vascular morphogenesis by regulating the number and size of the vessels, the area covered by the vessels, as well as the site and timing of anastomoses (Fig. 5j). We also speculate that RECK-dysfunction may underlie various conditions that give rise to fragile, leaky blood vessels, such as cancers39 and RASopathies40, since several activated oncogenes, including mutated RAS, strongly suppress RECK expression12,41. Compounds capable of upregulating endogenous RECK42 may be useful in ameliorating such conditions.

Methods

Mice

Animal experiments were approved by Animal Experimentation Committee, Kyoto University and conducted in accordance with its regulation. Generation and genotyping of mice carrying the ReckCrER (also known as Reck-CreERT2 or KI), ReckE1fx (also known as R1), Reck∆, or ReckLow (also known as R2neo) allele has been described elsewhere21. To evaluate the roles of Reck in mural cells, Reck+/∆ mice were crossed with mice carrying Sm22-Cre transgene30 to obtain Reck+/∆; Sm22-Cre male mice, which were then crossed with ReckE1fx/E1fx female mice, and their pups harvested at various stages for genotyping and morphological studies. To evaluate the roles of Reck in endothelial cells, Reck+/∆ mice were crossed with Tie2-Cre transgenic mice31 to obtain Reck+/∆; Tie2-Cre male mice, which were crossed with ReckE1fx/E1fx female mice, and their pups examined at various stages. To visualise cells expressing Tie2, Sm22, or Reck, female mice homozygous for the allele containing the mTmG transgene32 were crossed with male mice carrying the Tie2-Cre, Sm22-Cre, or ReckCrER transgene to obtain pups carrying both the mTmG and Cre transgenes. To test the roles of Reck in microvessel formation in vitro, Reck+/CrER; mTmG/mTmG male mice were crossed with ReckE1fx/E1fx female mice (both in ICR background), and ReckE1fx/CrER; mTmG mice (Reck cKO) were selected. To generate a matched control, Reck+/CrER male mice were crossed with mTmG/mTmG female mice, and Reck+/CrER; mTmG mice (Cont) were selected. Mice carrying the ReckCrER transgene were treated four times by daily intra-peritoneal injections of tamoxifen (80 mg/kg), and then two days later, aortae were harvested for ARA.

Histology

Mouse embryos were fixed, sliced (10 μm-thick), and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin21, by immunohistochemistry with anti-CD31, anti-αSMA, or anti-laminin27, or by Kluver-Barrera method43 as described previously. Tissues from mice carrying the mTmG reporter were fixed, incubated overnight in 30% sucrose, embedded in O.C.T, frozen at –80 oC, sliced (5μm-thick), and observed with a fluorescent microscope.

Aortic ring assay

ARA was performed following the protocol of Baker et al.29 with some modifications. The following conditions, optimised as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, were used unless otherwise stated. Thoracic aortae were dissected from 5-week old transgenic mice after overnight starvation. The peri-aortic fibroadipose tissue and blood were carefully removed with fine microdissecting forceps, and aorta tunics were preserved without damage. After cleaning, aortae were cut into 1 mm-thick rings, rinsed 3 times with PBS (−), and incubated overnight in Opti-MEM at 37 °C. The rings were then embedded in a mound of gel prepared on ice by mixing 5 volumes of 3 mg/ml collagen type I-A (Nitta Gelatin, Osaka, Japan), 3 volumes of 3 mg/ml collagen type IV (Nitta Gelatin, Osaka, Japan), 1 volume of 10× DMEM, and 1 volume of reconstitution buffer (2.2 g NaHCO3 in 100 ml of 0.05 N NaOH and 200 mM HEPES). For embedding, 50 μl of the collagen mixture was placed into wells of 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes to form a basal gel. Aortic rings were placed on the basal gel and covered with 10 μl of cold collagen mixture. After 20-min incubation at 37 °C, each well was fed with 200 μl Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20 ng/ml VEGFa (R&D systems), 5% fetal horse serum (Cell Culture Laboratories, Ohio, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The dishes were tightly sealed with parafilm, kept at 37 °C for two weeks, and examined every day under an inverted microscope. Micrographs were taken every day up to day 14 for morphometric analyses. In some experiments (Fig. 5c–i; Supplementary Fig. S7, S8c), bovine plasma fibronectin (Sigma, F1141) was added to the gel at 1 μg/ml.

Morphometry

Microscopic images were recorded with a digital camera at various time points and magnification, depending on the properties to be assessed: x40 on day 3 to 7 for microvessel growth (number and length), x100 on day 8 and 9 for microvessel width, and x200 on day 10 to 14 for the cells associated with microvessels. The images were analysed using ImageJ to determine the length, width, and anastomosis of microvessels and the area covered by them. The numbers of microvessels were counted manually, following the criteria described by Aplin et al.33, where outgrowth constituted by singular cells such as fibroblasts, pericytes, and macrophages or segmented sprout structures were not included. AngioTool44 was also employed to quantify microvessel area, branching points (total junctions), total length, end points, and lacunarity.

Immunofluorescent staining

Aortic rings extending microvessels were fixed with 4% formalin, permeabilised with 0.25% Triton-X for 15 min and incubated in PBS (+) containing 10% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature to block non-specific binding.After being rinsed with PBS (+) for 5 min they were then incubated overnight with primary antibody diluted in PBLEC29. After rinsing with PBS (+) (3 × 10 min), samples were then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a cocktail of Alexa Fluor (488, 555, or Cy5) conjugated with appropriate secondary antibodies in PBLEC. Samples were rinsed then incubated (1 min) with Hoechst33342 and mounted using Fluoromount (Diagnostic BioSystems). Images were recorded using a fluorescence microscope (OlympusX70 or Keyence BZ-9000). The following primary antibodies were used: laminin (Progen 10765), CD31 (BD Pharmingen 550274), Reck [RECK-F, polyclonal rabbit antibodies (Matsuzaki et al., in preparation) and 5B11D1212]; α-Sma (DAKO MO85), fibronectin (BD Biosciences, 610078), PDGFR-beta (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-432), Flk-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-625), LAMA5 (Sigma-Aldrich SAB4501720) and Ki67 (Leica Biosystems NCL-Ki67p).

Statistics

Quantitative data are presented in the form of mean ± sem in graphs. Significance of difference between two sets of data were assessed by Student’s t-test using the TTEST function in Excel (Microsoft), and the results are presented by symbols: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Almeida, G. M. et al. Critical roles for murine Reck in the regulation of vascular patterning and stabilization. Sci. Rep. 5, 17860; doi: 10.1038/srep17860 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by KAKENHI [Grants-in-Aid for Creative Scientific Research, Scientific Research on Priority Areas, and Scientific Research on Innovative Areas]. G.M.A. was a MEXT fellow. We are grateful to Emi Nishimoto, Hai-Ou Gu, Mika Fujiwara, and Kumi Kawade for technical assistance, Aki Miyazaki for secretarial assistance, and Claire Whitworth for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.Y., T.M. and M.N. designed, and M.Y. and G.M.A. performed, the experiments in vivo. T.M., G.M.A. and M.N. designed, and G.M.A. performed, most of the experiments in vitro. Y.M. and S.O. helped some experiments in vitro. T.M. and M.N. organized and supervised the study. G.M.A. and M.N. prepared the manuscript with the help of other authors.

References

- Yancopoulos G. D. et al. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature 407, 242–248 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak H. F. Discovery of vascular permeability factor (VPF). Exp Cell Res 312, 522–526 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saharinen P., Bry M. & Alitalo K. How do angiopoietins Tie in with vascular endothelial growth factors? Curr Opin Hematol 17, 198–205 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. & Jain R. K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473, 298–307 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung A. S. & Ferrara N. Developmental and pathological angiogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 27, 563–584 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geudens I. & Gerhardt H. Coordinating cell behaviour during blood vessel formation. Development 138, 4569–4583 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrae J., Gallini R. & Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev 22, 1276–1312 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger D. R. & Davis G. E. Angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3, a005090 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratman A. N. & Davis G. E. Endothelial cell-pericyte interactions stimulate basement membrane matrix assembly: influence on vascular tube remodeling, maturation, and stabilization. Microsc Microanal 18, 68–80 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-McCaw A., Ewald A. J. & Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8, 221–233 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessenbrock K., Plaks V. & Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 141, 52–67 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi C. et al. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and inhibition of tumor invasion by the membrane-anchored glycoprotein RECK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 13221–13226 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J. et al. The membrane-anchored MMP inhibitor RECK is a key regulator of extracellular matrix integrity and angiogenesis. Cell 107, 789–800 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M. et al. RECK: a novel suppressor of malignancy linking oncogenic signaling to extracellular matrix remodeling. Cancer Metastasis Rev 22, 167–175 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T. et al. The reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs (RECK) interacts with membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase and CD13/aminopeptidase N and modulates their endocytic pathways. J Biol Chem 282, 12341–12352 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraguchi T. et al. RECK modulates Notch signaling during cortical neurogenesis by regulating ADAM10 activity. Nat Neurosci 10, 838–845 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M. & Takahashi C. Recklessness as a hallmark of aggressive cancer. Cancer Sci 98, 1659–1665 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura A. et al. RECK forms cowbell-shaped dimers and inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-catalyzed cleavage of fibronectin. J Biol Chem 284, 3461–3469 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M. et al. Density- and serum-dependent regulation of the Reck tumor suppressor in mouse embryo fibroblasts. Cell Signal 21, 1885–1893 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loayza-Puch F. et al. Hypoxia and RAS-signaling pathways converge on, and cooperatively downregulate, the RECK tumor-suppressor protein through microRNAs. Oncogene 29, 2638–2648 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M. et al. The transformation suppressor gene Reck is required for postaxial patterning in mouse forelimbs. Biol Open 1, 458–466 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriely G. et al. MicroRNA 21 promotes glioma invasion by targeting matrix metalloproteinase regulators. Mol Cell Biol 28, 5369–5380 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. MicroRNA-342 inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation and invasion by directly targeting DNA methyltransferase 1. Carcinogenesis 32, 1033–1042 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H. M. et al. Keratinization-associated miR-7 and miR-21 regulate tumor suppressor reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs (RECK) in oral cancer. J Biol Chem 287, 29261–29272 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N. et al. Increased miR-222 in H. pylori-associated gastric cancer correlated with tumor progression by promoting cancer cell proliferation and targeting RECK. FEBS Lett 586, 722–728 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata H. et al. MicroRNA-182-5p promotes cell invasion and proliferation by down regulating FOXF2, RECK and MTSS1 genes in human prostate cancer. PLoS One 8, e55502 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandana E. P. et al. Involvement of the Reck tumor suppressor protein in maternal and embryonic vascular remodeling in mice. BMC Dev Biol 10, 84 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia R. F. & Ottinetti A. Growth of microvessels in serum-free matrix culture of rat aorta. A quantitative assay of angiogenesis in vitro. Lab Invest 63, 115–122 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. et al. Use of the mouse aortic ring assay to study angiogenesis. Nat Protoc 7, 89–104 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtwick R. et al. Smooth muscle-selective deletion of guanylyl cyclase-A prevents the acute but not chronic effects of ANP on blood pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 7142–7147 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanuki Y. Y. et al. Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev Biol 230, 230–242 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M. D. et al. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593–605 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin A. C., Fogel E., Zorzi P. & Nicosia R. F. The aortic ring model of angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol 443, 119–136 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka Y. et al. The membrane-anchored metalloproteinase regulator RECK stabilizes focal adhesions and anterior-posterior polarity in fibroblasts. Oncogene 28, 1454–1464 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki K. et al. E-cadherin-downregulation and RECK-upregulation are coupled in the non-malignant epithelial cell line MCF10A but not in multiple carcinoma-derived cell lines. Sci Rep 4, 4568 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsholtz C. Insight into the physiological functions of PDGF through genetic studies in mice. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15, 215–228 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijelath E. S. et al. Novel vascular endothelial growth factor binding domains of fibronectin enhance vascular endothelial growth factor biological activity. Circ Res 91, 25–31 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y., Ninomiya K., Hamada H. & Noda M. Involvement of the SKP2-p27(KIP1) pathway in suppression of cancer cell proliferation by RECK. Oncogene 31, 4128–4138 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel S. et al. Normalization of the vasculature for treatment of cancer and other diseases. Physiol Rev 91, 1071–1121 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauen K. A. The RASopathies. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 14, 355–369 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasahara R. M., Takahashi C. & Noda M. Involvement of the Sp1 site in ras-mediated downregulation of the RECK metastasis suppressor gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 264, 668–675 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai R. et al. A novel screen using the Reck tumor suppressor gene promoter detects both conventional and metastasis-suppressing anticancer drugs. Oncotarget 1, 252–264 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluver H. & Barrera E. A method for the combined staining of cells and fibers in the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 12, 400–403 (1953). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zudaire E., Gambardella L., Kurcz C. & Vermeren S. A computational tool for quantitative analysis of vascular networks. PLoS One 6, e27385 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.