Abstract

Inspired by the dendritic integration and spiking operation of a biological neuron, flexible oxide-based neuromorphic transistors with multiple input gates are fabricated on flexible plastic substrates for pH sensor applications. When such device is operated in a quasi-static dual-gate synergic sensing mode, it shows a high pH sensitivity of ~105 mV/pH. Our results also demonstrate that single-spike dynamic mode can remarkably improve pH sensitivity and reduce response/recover time and power consumption. Moreover, we find that an appropriate negative bias applied on the sensing gate electrode can further enhance the pH sensitivity and reduce the power consumption. Our flexible neuromorphic transistors provide a new-concept sensory platform for biochemical detection with high sensitivity, rapid response and ultralow power consumption.

With the recent interest in brain/computer interfaces1, soft robotics2, wearable electronics3 and skin-like sensory systems4, flexible devices have attracted growing attention. These emerging devices require new fabrication schemes that enable integration with soft, curvilinear and time-dynamic human tissues. Among these devices, flexible sensors are becoming increasingly significant in a wide-variety of novel applications such as in vivo monitoring5, delivery of advanced therapies6, artificial sense organs7, etc. As a fundamental component for sensor application, field-effect transistors (FETs) based sensors have been intensively investigated due to their inherent advantages of miniaturization, facilitated integration, direct transduction and label-free detection8,9,10,11. The classical sensing mechanism of the FET-based sensor is attributed to a charge-dependent interfacial potential due to the adsorption of potential-determining species at sensing membrane/electrolyte interface12. The sensitivity is limited to ~59.2 mV/decade (Nernst limit) at room temperature when the threshold voltage (Vth) is recorded as the output signal. It should be noted here that above mentioned measurements are based on the quasi-static electrostatic coupling mode, which potentially increases the time consumption and energy dissipation. But in smart sensory platforms, such as implantable devices and wearable sensory systems, low power consumption is one of the most important pre-requisites.

Synergic integration of presynaptic inputs from the dendrites plays an important role for sensory information process and cognitive computation, and the idea of building bio-inspired solid-state devices has been around for decades13,14. In 1992, Shibata et al. proposed Si-based neuron transistors with multiple input gates that are capacitively coupled to a floating gate15. The “on” or “off” state of the neuron transistors depends on the integrated effect of the multiple input gates. One of the unique features of the neuron transistors is the ultralow power dissipation during calculation due to the gate-level sum operation in a voltage mode. From then on, Si-based neuron transistors have attracted much attention for chemical and biological detection due to the easy adjustment of threshold voltage16,17,18,19,20. When an asymmetric gate capacitor structure is adopted, magnification of Vth shift can be observed in the neuron transistor when the sensing gate experiences a load from electrolyte. This device concept scales up the surface potential shift by the capacitance ratio between the sensing gate and the control gate21,22,23. But, up to now, flexible electrolyte-gated neuron transistors with amorphous oxide channel layers for biochemical sensing applications have not been reported.

Amorphous oxide-based transistors were proposed as promising fundamental unit in sensory platform due to their low process temperature, superior electrical properties, high reliability and easy reproducibility24,25,26. To date, remarkable sensing performances have been demonstrated in these oxide-based transistors27,28,29. For portable applications, low-voltage operation is preferred. Electrolyte gated electric-double-layer (EDL) transistors can act as potential candidates with a low operation voltage due to the strong EDL modulation at the electrolyte/channel interface30,31. Recently, oxide-based EDL transistors gated by solid-state inorganic electrolytes were proposed by our group32,33. At the same time, artificial synapses and neuromorphic transistors with low power consumption and fundamental biological functions were mimicked in these devices34,35,36. In the present work, flexible sensory platform based on individual protonic/electronic coupled indium-zinc-oxide (IZO) neuromorphic transistor was fabricated on plastic substrates. Such neuromorphic transistor exhibited a high sensitivity when a quasi-static dual-gate synergic modulation mode was adopted. Most importantly, single-spike dynamic sensing of such flexible neuromorphic transistor was also investigated, and pH sensing with ultra-high sensitivity, very quick response/recover time, and extremely low power consumption were realized.

Results

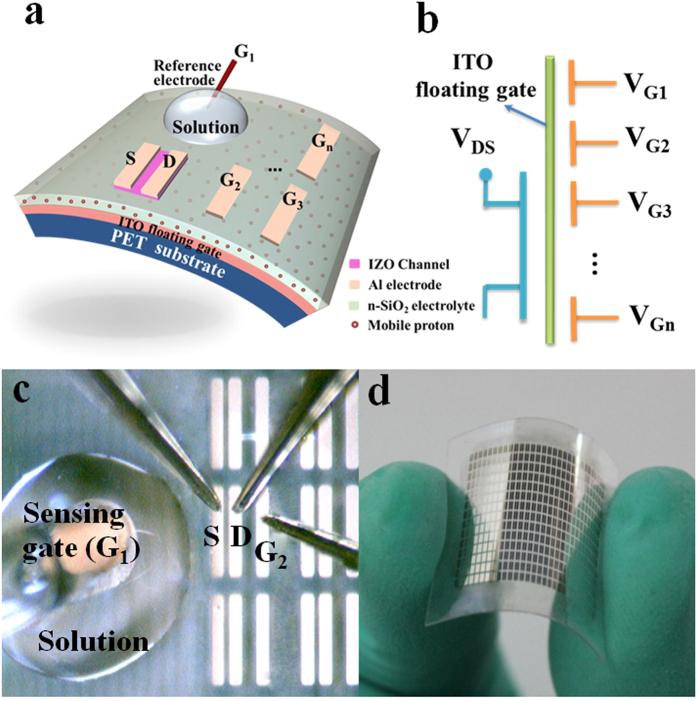

Figure 1a shows the schematic diagram of a flexible IZO-based neuromorphic transistor with multiple in-plane gate electrodes for pH sensing application. A miniature Ag/AgCl reference electrode immersed into a 5.0 μL pH buffer solution droplet on the nanogranular SiO2 (n-SiO2) electrolyte film acts as a sensing gate (G1). In-plane aluminum (Al) electrodes (G2, G3…Gn) are used as control gates. The distinctive feature of our device is that sensing gate and all control gates are located at the same plane. The capacitive network of the neuromorphic transistor is plotted in Fig. 1b. The carrier density of the IZO channel layer can be electrostatic modulated by the weighted sum of all inputs from the sensing and control gates. The weight for each gate is directly proportional to the capacitive factor normalized by the total capacitance of the floating gate5. Figure 1c displays the top-view optical image of the IZO-based neuromorphic transistor sensor. The channel width (W) and length (L) is 1000 and 80 μm, respectively. As a proof of concept, only one sensing gate and one control gate electrode is used in the present work. The distance between the control gate electrode and the drain electrode is 300 μm. Figure 1d shows a picture of the IZO-based neuromorphic transistor array on PET plastic substrate, exhibiting its flexible nature under external force.

Figure 1. IZO-based neuromorphic transistor on PET substrate and its flexibility exhibition.

(a) Schematic of the flexible pH sensor based on an IZO neuromorphic transistor with multiple gate electrodes. An Ag/AgCl reference electrode immersed in the solution droplet acts as the sensing gate. In-plane Al electrodes are used as the control gates. (b) The schematic image of the capacitive network of the flexible neuromorphic transistor. The carrier density of the IZO channel is modulated by the weighted sum of all inputs of sensing gate and control gates. (c) An optical microscope image of the system (Taken by Dr. Ning Liu). (d) The sensor array fabricated on a flexible PET substrate (Taken by Dr. Ning Liu).

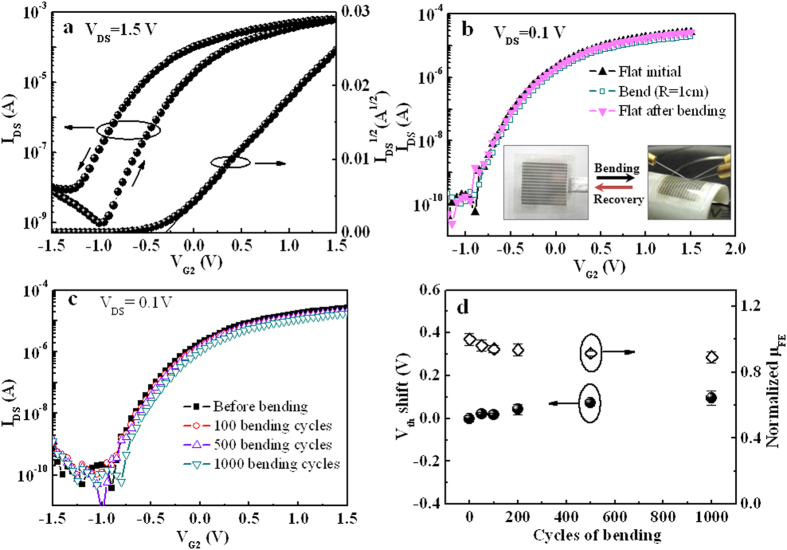

Figure 2a shows the transfer characteristics of the IZO-based EDL transistor at a constant VDS of 1.5 V. Gate voltage applied on lateral Al gate electrode is swept from −1.5 V to 1.5 V and then back. A clear anticlockwise hysteresis window of ~0.4 V is observed, which is likely due to the mobile protons within the nanogranular SiO2 electrolyte37. Subthreshold swings (SS), current on/off ratio (Ion/Ioff) and Vth are estimated to be ~175 mV/decade, ~6.4 × 105, and −0.3 V, respectively. In addition, field-effect electron mobility (μFE) at the saturation region is estimated to be ~12 cm2/V.s by the following equation:

Figure 2. Electrical properties the IZO-based neuromorphic transistor and its flexibility characteristics.

(a) Transfer curves of the IZO-based neuromorphic transistor measured by sweeping the voltage on the control gate (G2) at VDS = 1.5 V. An anticlockwise hysteresis loop of ~0.4 V is observed. (b) Transfer curves of the flexible neuromorphic transistor measured before, during and after bending by a cylinder with a radius of 1.0 cm. The inset is the pictures during the measurement process (Taken by Mr.Ning Liu). (c) Transfer curves of device measured before and after repeated bending cycles by sweeping the control gate (G2) at VDS = 0.1 V. (d) The variations in Vth and μFE of the flexible neuromorphic transistor with repetitive bending cycles. Error bars represent standard deviations for 5 samples.

|

where Ci (~2.7 μF/cm2) is the specific capacitance of the SiO2 electrolyte measured from two in-plane Al gate electrodes at 1.0 Hz (Supporting Figure S1). For practical flexible electronics application, flexible devices should be bendable without sacrificing their electrical properties. The influence of mechanical bending on the electrical characteristics of our devices was investigated. Figure 2b shows the transfer curves recorded before, during and after bending by a cylinder with a radius of 1.0 cm. The images of the measurement process are shown in the insets of Fig. 2b. Good reproducibility is obtained on different test conditions. Moreover, mechanical stress tests have also been performed by bending the sample repeatedly. Figure 2c shows the transfer curves recorded at repetitive bending cycles. The flexible neuromorphic transistors survive after more than 1000 flex/flat cycles with negligible change in the transfer characteristics. The variations in Vth and μFE with the repetitive bending cycles are extracted, as shown in Fig. 2d. After 1000 cycles of bending and recovery, a small positive shift of ~0.1 V in Vth and only ~10% reduction in μFE are measured. The results indicate that the flexible neuromorphic transistors have good mechanical reproducibility and durability.

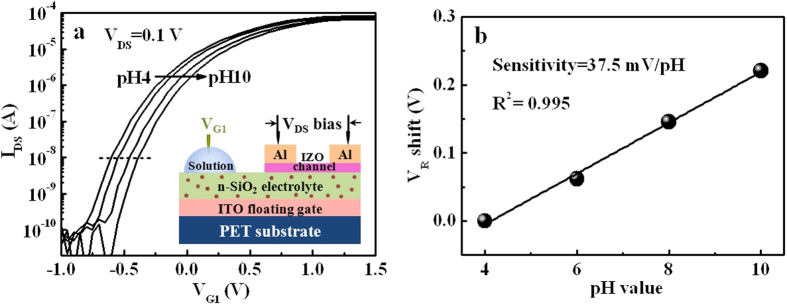

We will next study the pH sensing performance of the devices operated in the quasi-static mode. Figure 3a shows the transfer curves of the neuromorphic transistor based sensor operated at the linear region (VDS = 0.1 V) with the sensing gate immersed into solution droplets with different pH values. The inset in Fig. 3a shows the layout of this normal pH sensing measurement. Clear negative shift of the transfer curve is observed when pH value decreases from 10 to 4. It has been reported that acidic solution can give rise to a more positive surface potential due to the ionic interaction at the solution/SiO2 interface38,39. In our case, positive surface potential will make protons within SiO2 electrolyte migrate to the electrolyte/IZO channel interface, which will induce excess electrons in the IZO channel and a negative shift of transfer curve. When the gate voltage at a drain current of 10 nA is defined as the responsive voltages (VR), a sensitivity of ~37.4 mV/pH is realized, as shown in Fig. 3b. This value is comparable to the reported FET sensors using SiO2 as a sensing material40.

Figure 3. pH sensitivities of the IZO-based neuromorphic transistor measured in single-gate mode.

(a) Transfer curves of the neuromorphic transistor measured by using the sensing gate G1 at VDS = 0.1 V. The pH value of the solution droplet on the sensing gate G1 is changed from 4 to 10 at a step of 2. The inset shows the measurement schematic. (b) The sensitivity in terms of VR shift. The data can be fitted linearly by the black line. A sensitivity of ~37.5 mV/pH and a linearity of ~0.995 are obtained.

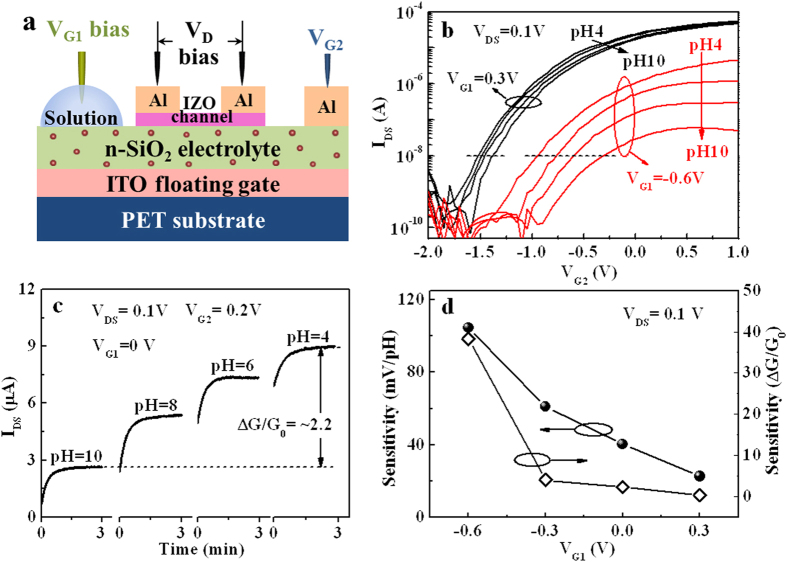

In order to improve the sensing performance of the IZO-based neuromorphic transistor, dual-gate synergic modulation mode is investigated. During the measurements, G1 is biased at different fixed voltages and G2 is swept from –2.0 to 1.0 V. The measuring schematic is shown in Fig. 4a. Figure 4b shows the transfer curves (IDS-VG2) curves measured at VDS = 0.1 V with pH value changed from 10 to 4 and VG1 fixed at 0.3 V and −0.6 V, respectively. Similarly, the transfer curves shift to the negative direction when the pH value decreases at a fixed VG1. Here, we should point out that more obvious shifts in the transfer curve are induced by pH variation when VG1 = −0.6 V. The sensitivity in terms of VR shift is plotted as a function of VG1 (Fig. 4d). The pH sensitivity increases when VG1 shifts from a positive value to a negative value. A maximal pH sensitivity of ~105 mV/pH is obtained when VG1 = −0.6 V. The improved sensitivity obtained at a negative VG1 is attributed to amplified capacitive coupling factor between these two gates (G1 and G2). Asymmetric dual-gate capacitive coupling can result in intrinsic amplification of the measured surface potential shifts. Theoretical analysis of the quasi-static pH sensing process can be found in Supporting Note 1. Jayant et al. also reported that this technique merely scaled the surface potential shift, but did not signify any change in the intrinsic properties of the electrolyte interface21. Figure 4c shows real-time responses of IDS of the IZO-based neuromorphic transistor sensor in different pH solutions for 180 s at fixed VDS = 0.1V, VG1 = 0 V and VG2 = 0.2V. It is observed that IDS increases gradually to a stable value. The steady IDS increases stepwise with discrete changes in pH value from 10 to 4. The sensitivity S of a sensor can also be defined as the relative change in channel conductance, S = (|G−G0|)/(G0) = ΔG/G041. In our case, the response conductance to pH = 10 is defined as G0. Therefore, the sensitivity (∆G/G0) is estimated to be ~2.2 for pH = 4 at equilibrium state. We also find that the sensitivity (∆G/G0) can be improved by a negative bias applied on sensing gate (G1), as shown in the right axis of Fig. 4d. A highest sensitivity of ~38.3 is obtained at a fixed VG1 of −0.6 V. This value is much higher than those reported in nanoscale transistor sensors42,43. This is because that an appropriate negative voltage applied on the sensing gate (G1) can make the neuromorphic transistor operated in the subthreshold regime, in which the sensitivity in terms of current variation can be exponentially enhanced due to the most effective gating effect of charges bound on a surface44.

Figure 4. pH sensitivities of IZO-based neuromorphic transistor measured in dual-gate synergic modulation mode.

(a) The schematic image of the measurements. (b) Transfer curves of the device measured by applying sweep voltage on the control gate (G2) at VDS = 0.1 V with different fixed voltages applied on G1. pH value of the solution droplet on G1 increases from 4 to 10 at a step of 2. (c) The real-time responses of IDS for IZO neuromorphic transistor sensors in each pH solution for 180s at VDS = 0.1V, VG1 = 0V and VG2 = 0.2V. (d) The sensitivity in terms of VR shift and ΔG/G0 at different VG1.

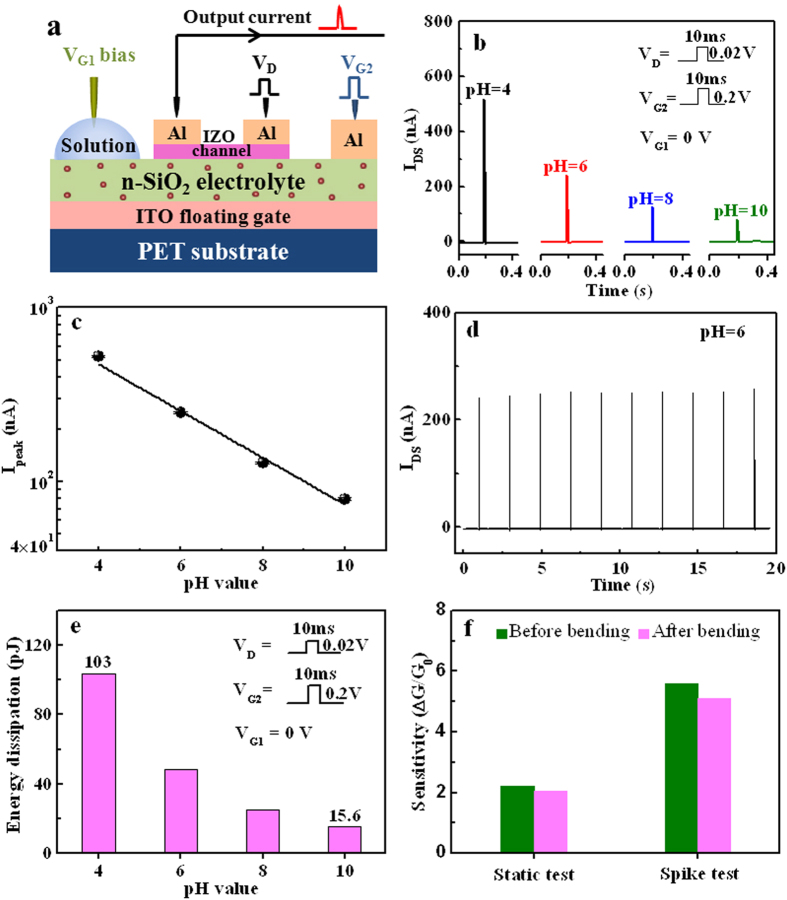

Next, inspired by the spiking operation mode of a biological neuron, we have investigated the single-spike pH sensing performance of our neuromorphic transistor sensors. Due to the distinctive dynamic characteristics of the proton migration, our device presents a unique time dependent transient property. During the measurement, equilibrium is disturbed by a small voltage pulse applied on the control gate (G2). The dynamic spike current response to such a disturbation contains the pH sensing information. After the detection, the device will quickly recover to the original equilibrium state. Moreover, during the single-spike sensing process, the energy consumption is extremely low, which is preferred for portable and wearable sensory applications. The single-spike pH sensing measurement of the detection is schematically illustrated in Fig. 5a. At first, a disturbing spike VG2 (0.2 V, 10 ms) was applied on control gate (G2), and a synchronous reading spike VD (0.02 V, 10 ms) was applied on drain electrode to measure the output current. As shown in Fig. 5b, when the pH value is changed from 4 to 10, the response current (IDS) decreases from 512 to 80 nA. We also find that the logarithm of IDS decreases linearly with increasing pH value, and a high sensitivity (∆G/G0) of ~5.6 is estimated, as shown in Fig. 5c. The characteristic time of the dynamic process of proton migration in the nanogranular SiO2 electrolyte is in the order of few milliseconds. The response/recover time is estimated to be ~5.0 milliseconds, which is much shorter than that operated in quasi-static mode. The reproducibility of the single-spike pH sensing measurement is also investigated. Figure 5d shows the response currents stimulated by repeated voltage pulse spikes with pH = 6. The results indicate a good reproducibility of single-spike detection of pH values. If we define the value of σ(Ip)/Ave(Ip) as the noise factor, where σ(Ip) is the standard variation of the repeated spike current peaks, and Ave(Ip) is the average value of repeated spike current peaks. The value of σ(Ip)/Ave(Ip) is calculated to be only ~1.7% for pH = 6. Detailed analysis of the reproducibility and noise of the spike sensing can be found in Supporting Note 2. The power consumption of our system can be estimated by multiplying the reading voltage, the channel current and the spike duration time45. Figure 5e shows the average energy dissipation for single-spike pH detection in each pH value from 10 to 4 with a spike duration time of 10 ms. The power consumption reduces from 103 pJ/spike to 15.6 pJ/spike when the pH value increases from 4 to 10. Of course, the power consumption can be further reduced by reducing the spike voltage and spike duration time. The influence of bending on the sensitivity is also investigated. As shown in Fig. 5f, after 1000 bending cycles, the sensitivity reduction is less than 10% for both quasi-static and single-spike sensing modes.

Figure 5. pH sensing performances of IZO-based neuromorphic transistor operated in a single-spike mode.

(a) Schematic diagram of single-spike pH sensing measurements. (b) Single-spike measurement is performed for pH value increases from 4 to 10. The spike voltage VG2 (0.02V, 10 ms) and the reading voltage VD (0.2 V, 10 ms) are applied synchronously. The reference electrode VG1 is grounded. (c) The logarithm of IDS peak changes linearly with the pH value of the solution. The error bars represent standard deviations for 10 samples. (d) Reproducibility of the neuromorphic transistor sensor with pH = 6. (e) pH value dependent energy dissipation operated in single-spike mode. (f) The influence of 1000 times bending on the sensitivity of the neuromorphic transistor for both quasi-static and single-spike sensing modes. Fixed biases (VDS = 0.1 V, VG1 = 0 V, VG2 = 0.2 V) are applied in quasi-static mode. Synchronous pulse voltages VG2 (0.2 V, 10 ms) and VD (0.02 V, 10 ms) with fixed VG1 bias of 0 V are applied in dynamic spiking mode.

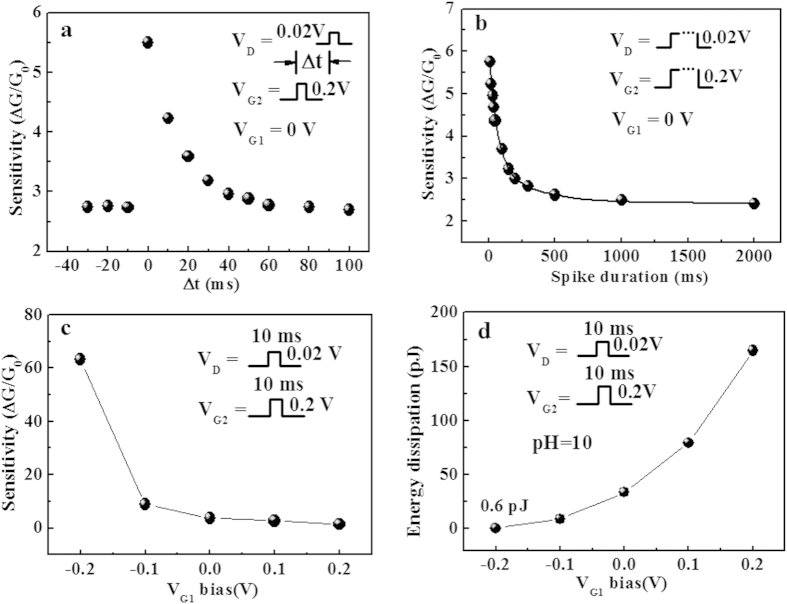

The single-spike sensing performance implemented with an asynchronous reading spike is also investigated. Figure 6a shows the sensitivity as a function of the inter-spike interval (Δt) between VD and VG2. If Δt < 0, the reading spike VD is applied before VG2. In this case, the protonic disturbance does not happen in the sensing process, thus the sensitivities are close to the equilibrium state and a sensitivity (∆G/G0) of ~2.7 is obtained. When Δt ≥ 0, the measured sensitivity is time interval (Δt) dependent. A highest pH sensitivity (∆G/G0) of ~5.6 is obtained when Δt = 0 and it gradually reduces to 2.7 with increasing Δt. Figure 6b shows the sensitivity as a function of spike duration time. At present, in order to accurately measure a low current in the nA scale by semiconductor analyzer, the shortest spike duration we can used is 10 ms. In this case, the maximal pH sensitivity (∆G/G0) is measured to be ~5.6. We can anticipate that the sensitivity can be improved further when the spike duration time is reduced further. Detailed theoretical analysis of the influence of spike duration on the sensitivity can be found in Supporting Note 3. We also find that the sensitivity decreases gradually to ~2.4 when the spike duration increases to 2 s. These results indicate that the neuromorphic transistor sensor tends to arrive at equilibrium state with the increase of spike duration. The sensitivity of single-spike pH sensing performances of our neuromorphic transistor sensor can be improved further by additional gate synergic modulation. Figure 6c shows the influence of voltage bias applied on G1 on the sensitivity when the device is operated in single-spike mode. The pH sensitivity increases when VG1 shifts from positive to negative. A maximum sensitivity (∆G/G0) of ~63 can be obtained when a negative voltage of −0.2 V is applied on G1. We also investigated the influence of voltage bias applied on VG1 on the energy dissipation of single-spike sensing measurement. Our results indicate that the energy dissipation can be gradually reduced when the VG1 is changed from 0.2V to −0.2 V. As shown in Fig. 6d, an ultra-low energy dissipation of ~0.6 pJ/spike is estimated for pH = 10 at VG1 = −0.2 V with the spike duration of 10 ms. Similar to the quasi-static synergic mode, an appropriate negative VG1 can make the device operate in the subthreshold regime. Thus, an enhanced sensitivity can be obtained. At the same time, negative bias can reduce the spike sensing current, which is critical for energy dissipation reduction.

Figure 6. Influences of measuring parameters on the spike sensing performance.

(a) The sensitivity as a function of the inter-spike interval between VD and VG2 for asynchronous spiking sensing test. (b) The changes in sensitivity with spike duration. The solid line is the fitted curve. (c) The changes in sensitivity and energy dissipation (pH = 10) with various VG2 spike amplitude for synchronous spiking sensing test. (d) The changes in sensitivity and energy dissipation (pH = 10) against various VG1 bias.

The use of EDL electrolyte as gate dielectrics in flexible neuromorphic transistors can obviously reduce the operation voltage down to 2.0 V. Our results also demonstrate that spiking operation could greatly reduce the power consumption because the device is usually biased at zero voltage and only low voltage spikes with very short duration time are applied. Such neuromorphic transistors are favorable for flexible and portable sensor applications. Inspired by biological neuron, our neuromorphic transistor is designed with multiple in-plane gates. At present, we only investigate the influence of the second gate on the sensing performances in both quasi-static and spiking modes. Such devices can also be proposed as multi-functional sensors, where one in-plane gate acts as modulation terminal, one in-plane gate acts as calibration terminal, and other in-plane gates act as sensing input terminals. In the future, multiple-gate stochastic resonance effects may also be explored for further sensitivity improvements and power consumption reductions when such multiple-gate devices are operated in neuromorphic sensing mode.

In summary, flexible oxide-based neuromorphic transistors were fabricated on plastic substrates. A pH sensitivity of ~105 mV/pH was obtained for quasi-static dual-gate synergic sensing mode. Our results demonstrated that single-spike dynamic sensing mode could remarkably improve the pH sensitivity and reduce response/recover time and power consumption. We also found that appropriate depression voltage applied on the sensing gate could further enhance the pH sensitivity and reduce the power consumption. Our results provided a novel strategy for fabricating biochemical sensors with high sensitivity, rapid response and ultralow power consumption.

Methods

Fabrication of flexible oxide-based neuromorphic transistors

First, 500-nm-thick nanogranular SiO2 electrolyte films were deposited on ITO-coated PET substrates by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) at room temperature. SiH4 (95% SiH4 + 5% PH3) and pure O2 were used as reactive gases. Then, 30-nm-thick IZO channel layer was sputtered on the SiO2 electrolyte films by using a nickel shadow mask. The sputtering was performed at a RF power of 100 W and a working pressure of 0.5 Pa using an IZO target. The channel width and length were 1000 and 80 μm, respectively. Finally, 100-nm-thick Al source/drain electrodes and in-plane gate electrodes were deposited by thermal evaporation patterned by another shadow mask.

Preparation of pH solution

pH solutions were prepared by titrating 10 mM phosphate solution with dilute hydrochloric acid or potassium hydroxide solutions. The pH value of the solutions was monitored by a commercial pH meter. All chemicals were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (China). Such phosphate buffered solutions were used for measurements due to their strong buffer capacity to the influence of external environment. Thus, the changes in pH signal due to relaxation of charges in oxide can be ignored.

Electrical and sensing performance characterizations

The sensing area of the device was immersed in deionized water for 24 hours before measurements. Frequency-dependent capacitances of the SiO2 electrolyte films were characterized by a Solartron 1260A Impedance Analyzer in air ambient with a relative humidity of ~55%. Transistor characteristics and pH sensing performance were recorded by a semiconductor parameter characterization system (Keithley 4200 SCS) at room temperature. After each pH value test, the solution droplet was removed and the sensing area was rinsed two times in deionized water.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, N. et al. Flexible Sensory Platform Based on Oxide-based Neuromorphic Transistors. Sci. Rep. 5, 18082; doi: 10.1038/srep18082 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (Grant No. 61425020), and in part by the National Program on Key Basic Research Project (2012CB933004), and in part by a Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and in part by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Fund (LR13F040001).

Footnotes

Author Contributions The manuscript was prepared by N.L., L.Q.Z., F.P. and Q.W. Device fabrication was fabricated by N.L. and Y.H.L. Measurements were performed by N.L. and C.J.W. The project was guided by Q.W. and Y.S.

References

- Jeong J. W. et al. Materials and optimized designs for human-machine interfaces via epidermal electronics. Adv. Mater. 25, 6839–6846 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llievshi F., Mazzeo A. D., Shepherd R. E., Chen X. & Whitesides G. M. Soft robotics for chemists. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 50, 1890–1895 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W. et al. Fiber-based wearable electronics: A review of materials, fabrication, devices, and applications. Adv. Mater. 26, 5310–5336 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. et al. Flexible polymer transistors with high pressure sensitivity for application in electronic skin and health monitoring. Nat. Commun. 4, 1859 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban G. et al. Miniaturized multienzyme biosensors integrated with pH sensors on flexible polymer carriers for in vivo applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 7, 733–739 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Dewire J. & Calkins H. State-of-the-art and emerging technologies for atrial fibrillation ablation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 129–138 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. J. et al. Ultrasensitive flexible graphene based field-effect transistor (FET)-type bioelectronic nose. Nano Lett. 12, 5082–5090 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergveld P. Thirty years of ISFETOLOGY - What happened in the past 30 years and what may happen in thenext 30 years. Sens. Actuators, B 88, 1–20 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Joo S. & Brown R. B. Chemical sensors with integrated electronics. Chem. Rev. 108, 638–651 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S. et al. Ultralow voltage, OTFT-based sensor for label-free DNA detection. Adv. Mater. 25, 103–107 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern E. et al. Label-free immunodetection with CMOS-compatible semiconducting nanowires. Nature 445, 519–522 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkman M. et al. Dual-Gate Thin-Film Transistors, Integrated Circuits and Sensors. Adv. Mater. 23, 3231–3242 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N. et al. Nonlinear dendritic integration of sensory and motor input during an active sensing task. Nature 492, 247–251 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N. Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 9, 206–221 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T. & Ohmi T. A functional MOS-transistor featuring gate-level weighted sum and threshold operations. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 39, 1444–1445 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Shen N. Y., Liu Z., Lee C., Minch B. A. & Kan E. C. Charge-based chemical sensors: a neuromorphic approach with chemoreceptive neuron MOS (CνMOS) transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 50, 2171–2178 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Shen N. Y., Liu Z., Jacquot B. C., Minch B. A. & Kan E. C. Integration of chemical sensing and electrowetting actuation on chemoreceptive neuron MOS (CνMOS) transistors. Sens. Actuators, B 102, 35–43 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Jacquot B. C., Munoz N., Branch D. W. & Kan E. C. Non-Faradaic electrochemical detection of protein interactions by integrated neuromorphic CMOS sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 23, 1503–1511 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingebrandt S., Yeung C. K., Krause M. & Offenhausser A. Neuron-transistor coupling: interpretation of individual extracellular recorded signals. Eur. Biophys. J. 34, 144–154 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquot B. C., Lee C., Shen Y. N. & Kan E. C. Time-resolved charge transport sensing by chemoreceptive neuron MOS transistors (CνMOS) with microfluidic channels. IEEE Sens. J. 7, 1429–1434 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Jayant K. et al. Programmable ion-sensitive transistor interfaces. I. Electrochemical gating. Phys. Rev. E 88, 012801 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go J., Nair P. R. & Alam M. A. Theory of signal and noise in double-gated nanoscale electronic pH sensors. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 034516 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaisti M., Zhang Q., Prabhu A., Lehmusvuori A. & Rahman A. An ion-sensitive floating gate FET model: operating principles and electrofluidic gating. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 62, 2628–2635 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K. et al. Room-temperature fabrication of transparent flexible thin-film transistors using amorphous oxide semiconductors. Nature 432, 488–492 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato E., Barquinha P. & Martins R. Oxide semiconductor thin-film transistors: a review of recent advances. Adv. Mater. 24, 2945–2986 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. et al. Approaches to label-free flexible DNA biosensors using low-temperature solution-processed InZnO thin-film transistors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 55, 99–105 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H. J., Gu J. G. & Cho W. J. Sensitivity enhancement of amorphous InGaZnO thin film transistor based extended gate field-effect transistors with dual-gate operation. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 181, 880–884 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Guo D. et al. Indium-tin-oxide thin film transistor biosensors for label-free detection of avian influenza virus H5N1. Anal. Chim. Acta. 773, 83–88 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J. et al. Low-cost label-free electrical detection of artificial DNA nanostructures using solution-processed oxide thin-film transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 10715–10720 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buth F., Donner A., Sachsenhauser M., Stutzmann M. & Garrido J. A. Biofunctional electrolyte-gated organic field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 24, 4511–4517 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S. P., Dorfman K. D. & Frisbie C. D. Label-free DNA sensing platform with low-voltage electrolyte-gated transistors. Anal. Chem. 87, 1861–1866 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A., Sun J., Jiang J. & Wan Q. Microporous SiO2 with huge electric-double-layer capacitance for low-voltage indium tin oxide thin-film transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 222905 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Wan Q., Sun J. & Lu A. Ultralow-voltage transparent electric-double-layer thin-film transistors processed at room-temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 152114 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. Q., Wan C. J., Guo L. Q., Shi Y. & Wan Q. Artificial synapse network on inorganic proton conductor for neuromorphic systems. Nat. Commun. 5, 3158 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C. J., Zhu L. Q., Zhou J. M., Shi Y. & Wan Q. Inorganic proton conducting electrolyte coupled oxide-based dendritic transistors for synaptic electronics. Nanoscale 6, 4491–4497 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Liu N., Zhu L., Shi Y. & Wan Q. Energy-Efficient Artificial Synapses Based on Flexible IGZO Electric-Double-Layer Transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 36, 198–200 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Lu A., Sun J., Jiang J. & Wan Q. Low-voltage transparent electric-double-layer ZnO-based thin-film transistors for portable transparent electronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 043114 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fung C. D., Cheung P. W. & Ko W. H. A generalized theory of an electrolyte-insulator-semiconductor field-effect transistor. IEEE Trans. Eelecron Devices ED-33, 8–18 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Van Hal R. E. G., Eijkel J. C. T. & Bergveld P. A general model to describe the electrostatic potential at electrolyte oxide interfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 69, 31–62 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Van Hal R. E. G., Eijkel J. C. T. & Bergveld P. A novel description of ISFET sensitivity with the buffer capacity and double-layer capacitance as key parameters. Sens. Actuators, B 24, 201–205 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Nair P. R. & Alam M. A. Design considerations of silicon nanowire biosensors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 54, 3400 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Wei Q. Q., Park H. K. & Lieber C. M. Nanowire nanosensors for highly sensitive and selective detection of biological and chemical species. Science 293, 1289–1292 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao A. et al. Enhanced sensing of nucleic acids with silicon nanowire field effect transistor biosensors. Nano Lett. 12, 5262–5268 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X. P., Zheng G. & Lieber C. M. Subthreshold regime has the optimal sensitivity for nanowire FET biosensors. Nano Lett. 10, 547–552 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Chen C. L., Truong Q., Shen A. M. & Chen Y. A carbon nanotube synapse with dynamic logic and learning. Adv. Mater. 25, 1693–1698 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.