Abstract

Centrioles are essential for ciliogenesis. However, mutations in centriole biogenesis genes have been reported in primary microcephaly and Seckel syndrome, disorders without the hallmark clinical features of ciliopathies. Here we identify mutations in the master regulator of centriole duplication, the PLK4 kinase, and its substrate TUBGCP6 in patients with microcephalic primordial dwarfism and additional congenital anomalies including retinopathy, extending the human phenotype spectrum associated with centriole dysfunction. Furthermore, we establish that different levels of impaired PLK4 activity result in growth and cilia phenoptyes, providing a mechanism by which microcephaly disorders can occur with or without ciliopathic features.

Centrioles are microtubule-based structures that form the core of the centrosome and nucleate cilia and flagella. Centrioles are therefore key components of many cellular processes including cell division, signalling and motility1,2. Centriole number is tightly regulated during the cell cycle to ensure accurate chromosome segregation at mitosis3,4. During G1 the cell possesses two centrioles, which are duplicated during S and G2. Pericentriolar material (PCM) then forms around each pair of centrioles forming two centrosomes which separate and move to opposite ends of the cell to coordinate bipolar spindle formation and chromosome segregation.

A core set of evolutionary conserved proteins are required for centriole biogenesis (reviewed in ref2,5). Many of these components have been implicated in human microcephalic disorders6-11. Mutations in CPAP, CEP152, CEP135, CEP63 and STIL have been identified in primary microcephaly, an autosomal recessive disorder of cerebral cortex size, whereas mutations in two of these genes (CPAP and CEP152) can also cause microcephalic primordial dwarfism, in which extreme reduction in brain size is seen alongside prenatal and postnatal reduction in body size. No ciliopathy-associated phenotypes have been reported in any of these cases.

Here we report the identification of mutations in PLK4, and its phosphorylation target, TUBGCP6, extending the phenotypic spectrum associated with centriole biogenesis genes.

Results

Identification of mutations in PLK4 and TUBGCP6

A consanguineous family with seven affected individuals with microcephalic dwarfism from the Northern Territories of Pakistan was ascertained (Fig. 1a, Table 1, Table S1). Genome-wide linkage studies on this family by Illumina BeadChip SNP genotyping established a new disease locus of 11.7 Mb comprising 56 genes on chromosome 4 with a statistically significant LOD score of Z=4.7 (Fig. S1a,b). Exome sequencing of one affected individual from this family identified a homozygous intronic mutation c.2811-5C>G in Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), which was subsequently confirmed by capillary sequencing in this and other affected family members. This mutation was predicted to create a new splice acceptor site in intron 15, incorporating 4 bp of intronic sequence into the transcript, causing a frameshift and premature truncation of PLK4, p. Arg936Serfs*1 (Table 1). The variant was not present in 286 Pakistani controls or in 1000 Genomes and NHLBIGO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) public variant databases.

Figure 1. PLK4 and TUBGCP6 patients exhibit extreme microcephaly and short stature.

a) Family 1, a large consanguineous Pakistani family with microcephalic primordial dwarfism. * indicates family members from whom DNA was available.

b) Photographs of PLK4 and TUBGCP6 patients, P7, P9, P10, P11.

c) Head circumference is disproportionately reduced relative to height. Growth parameters plotted as standard deviations (z-score) from the population mean for age and sex. Circles, PLK4; squares, TUBGCP6 patients. OFC, occipitofrontal circumference, Hgt, height.

d) Axial T2 weighted MRI imaging showing that the cerebral cortex is substantially reduced in size with simplified gyral folding. P1 at 18 months (OFC −14.0 s.d) and P6 (OFC −9.0 s.d) at 20 years. Below, images from age-matched controls. Scale bar = 2cm.

Table 1. Clinical summary of patients with PLK4 or TUBGCP6 mutations.

| Family | Individual | Ancestry | Gene | Mutation(s) | Age (yrs) | OFC (s.d.) | Height (s.d.) | Eye, CNS and other congenital anomalies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P1 | Pakistan | PLK4 | Arg936fs | 12 | −7.4 | −4.6 | microcornea, cataract |

| 1 | P2 | Pakistan | PLK4 | Arg936fs | 5 | −14.0 | −6.9 | microphthalmia, cataract, arachnoid cyst |

| 1 | P3 | Pakistan | PLK4 | Arg936fs | 10.5 | −13.5 | −8.3 | polydactyly right foot, talipes |

| 1 | P4 | Pakistan | PLK4 | Arg936fs | 1.5 | −15.1 | −8.1 | microphthalmia |

| 1 | P5 | Pakistan | PLK4 | Arg936fs | 0.7 | −14 | NA | deceased - CHD |

| 2 | P6 | Madagascar | PLK4 | Phe433fs | 20 | −9.0 | −5.6 | retinopathy, deafness |

| 3 | P7 | Iran | PLK4 | Phe433fs | 5 | −12.8 | −5.1 | arachnoid cyst, no eye exam |

| 4 | P8 | Kuwait | TUBGCP6 | His1445fs | 3 | −11.1 | −3.3 | retinopathy, severe hyperopia |

| 5 | P9 | Canada | TUBGCP6 | Arg739Ter, Glu849Gly | 3 | −8.8 | −2.3 | retinopathy, triphalangeal thumbs, CHD |

| 6 | P10 | Europe & | TUBGCP6 | His1055Tyr(ss), Gly1198Ter | 16 | −10.0 | −3.45 | microphthalmia, retinopathy |

| 6 | P11 | S. America | TUBGCP6 | His1055Tyr(ss), Gly1198Ter | 9 | −7.2 | −2.1 | retinopathy, retinal folds, cataract |

Yrs, age in years at examination time of measurements. OFC, occupitofrontal circumference. s.d. standard deviations from the population mean. ss, splice site created by mutation. CHD, congenital heart disease. (P9 OFC at age 9 yr)

Independently, exome sequencing was also performed on a 15 year-old African patient with extreme microcephaly, short stature, retinopathy and deafness (Patient P6, Table 1). After common variant filtering (MAF>0.005), analysis under a recessive model of inheritance identified a homozygous frameshift mutation in exon 5 of PLK4, c.1299_1303delTAAAG, (p.Phe433Leufs*6), which was confirmed by capillary sequencing (Table 1) and was not detected in 364 control chromosomes. Additionally, this variant was not present in the 1000 Genome database and was reported in the ESP database with an allele frequency of 0.00016, in keeping with a causative mutation for a rare recessive disorder.

Capillary resequencing of the coding exons and splice junctions of PLK4 in 318 primary microcephaly and primordial dwarfism patients led to the identification of a second patient homozygous for the same c.1299_1303delTAAAG mutation. Strikingly, the two patients were from entirely distinct geographical regions: P6 from Madagascar and P7 from Iran. However, microsatellite genotyping of the region surrounding PLK4 identified an ancestral haplotype shared by both patients, extending 2.9 Mb from 126.3 Mb to 129.2 Mb on chromosome 4 (NCBI build 19) (Fig. S1c) consistent with shared remote ancestry many generations previously.

As PLK4 is a key regulator of centriole biogenesis12,13 and given the genetic mapping data with independent identification of distinct mutations that substantially disrupt gene function, we therefore concluded that PLK4 was a novel disease gene.

Phenotypically, patients displayed profound microcephaly (-11.6 s.d. +/−2.7) and substantial growth retardation of prenatal onset, with markedly reduced current height (-5.5 s.d. +/− 2.1) in keeping with the diagnosis of microcephalic primordial dwarfism (Fig. 1c, Table 1, Table S1) on the primary microcephaly-Seckel syndrome spectrum14. Severe intellectual disability was evident in all cases, and in some individuals there were additional neurological deficits (Supplementary Note). Neuroimaging demonstrated marked reduction in cortical size with simplified gyral folding (Fig. 1d). Cerebellar and brain stem size were also reduced with collections of increased cerebrospinal fluid evident, particularly in P2 and P7 in which large interhemispheric arachnoid cysts were seen (Fig. S2c,e).

Ocular anomalies were also frequently observed. In Family 1 eye size was reduced in some affected individuals, most prominently in P4, in which complete absence of one eye was seen (MRI, Fig. S2c). In patient P6 detailed ophthalmological assessment was available; fundus examination revealed pale optic discs, thin retinal vessels and bilateral macular atrophy. The ERG was non-recordable, reflecting a severe generalized retinopathy. Subsequent exome sequencing of an unrelated patient with primordial dwarfism and retinopathy identified a homozygous frameshift mutation in TUBGCP6 (c.4333insT, p.His1445Leufs*24). In this patient, the ERG also demonstrated complete absence of rod and cone function. Notably, TUBGCP6 is a direct phosphorylation target of PLK415, suggesting that these genes may act in the same cellular pathway to cause the microcephaly and retinopathy phenotypes. Subsequent screening of 12 additional patients with microcephaly and retinal dystrophy identified three further cases with TUBGCP6 mutations, all of which were phenotypically similar to the PLK4 patients (Table 1, Table S1, Supplementary Note). As with Family 1, micropthalmia was also seen in Family 6. Identification of these mutations substantiates a previous case report of microcephaly and chorioretinopathy in an Amish patient in which a homozygous TUBGCP6 anti-termination codon mutation was detected by exome sequencing16. Given prior publication on TUBGCP6, we focused subsequent investigation on the functional consequences of mutations in PLK4, given its central importance in centriole biogenesis12,13 and availability of PLK4 patient primary cell lines.

Transcriptional and protein consequences of PLK4 mutations

In Family 1, the c.2811-5C>G mutation was predicted to create a new splice acceptor site, adding an additional 4 bp of intron 15 sequence to the transcript resulting in premature truncation of PLK4 protein in the last polo-box domain (Fig. 2a,b). RT-PCR confirmed that this mutation altered splicing (Fig. 2c), with no residual wild-type transcript detectable in patient RNA (Fig. S3a).

Figure 2. Transcriptional and protein consequences of PLK4 mutations.

a) Schematic of the human PLK4 gene. Coding exons (black), UTRs (white), alternatively spliced region in exon 5 (grey), arrow heads, RT-PCR primer positions.

b) PLK4 protein domain structure. Kinase domain (KD)( grey), PEST sequences (1-3) (black), polo-box domains (PBD1-3) (blue/turquoise/green). Middle panel, the c.2811-5G>C mutation creates a new splice acceptor site that leads to retention of 4 bp of intron 15 sequence in the PLK4 mRNA, resulting in premature truncation of the protein at its C-terminus, disrupting the terminal polo-box domain (PB3). Lower panel depicts domain structure for the alternative isoform (ALT) resulting from use of an internal exon 5 splice donor site.

c) Sequence electropherograms of the exon 15-16 junction of PLK4 amplified by RT-PCR from patient and control RNA.

d) Alternative splicing of an internal exon 5 splice donor site is not detected in other vertebrates by RT-PCR.

e) Levels of functional PLK4 are reduced to 25% of normal levels, in patients with the c.1299_1309delTAAAG mutation. Transcript levels plotted from quantitative RT-PCR on RNA extracted from patient primary fibroblast cell lines (n=3 experiments (exp), performed in triplicate; error bars, s.e.m). P value, two-tailed t-test *p≤0.05. Further details and characterization of PLK4 ALT and FL transcript levels, Fig. S5.

f) Immunoblotting demonstrates reduced endogenous PLK4 protein levels in patient fibroblasts. Cell lysates of asynchronous cells. Left two lanes, RNAi of PLK4 in RPE1 cells demonstrating specificity of PLK4 antibody, with two PLK4-specific protein bands visualized. Remaining lanes, patient and control primary fibroblasts, upper panel standard exposure PLK4 immunoblot with middle panel overexposed to demonstrate residual detectable protein in P1 patient. Note also loss of the upper PLK4 band in P6 and P7. Lower panel, loading control, blot probed with anti-Actin antibody.

g) PLK4 protein levels at the centrosome are reduced in patient fibroblasts. Top panel, representative immunofluorescence images of primary fibroblasts treated with 10μM MG132 for 5 hrs prior to fixation. (Specificity of the anti-PLK4 antibody confirmed by performing RNAi-mediated PLK4 depletion, Fig. S6). Scale bar = 10 μm. Bottom panel, quantitation of PLK4 protein levels at the centrosome by immunofluorescence analysis. Exp=3, n=50 cells/exp; error bars, s.e.m of n=150 cells. P value, two-tailed t-test ****p≤0.0001.

In Families 2 and 3, the homozygous c.1299_1303delTAAAG mutation in exon 5 of PLK4 (Fig. 2a,b) results in a frame shift that generates an early termination codon, p. Phe433Leufs*6, predicted to result in complete abrogation of protein function as key functional domains are lost. As Plk4 is essential for mouse embryonic development17 this was surprising and prompted further investigation. Splice site prediction (Alamut, Interactive Biosoftware) identified an alternative splice donor site 42 bp upstream of the deletion and so we postulated that alternative splicing might partially rescue PLK4 function, with use of this splice donor site bypassing the deletion, leading to an in-frame loss of 60 amino acids (Fig. 2a,b). To confirm the existence of this alternative transcript in humans, we performed RT-PCR with primers in exon 5 and 6 that spanned the alternative and known splice donor sites in exon 5. Both splice forms, henceforth denoted FL and ALT respectively, were detected ubiquitously in adult tissues, fetal brain, retina, and neural progenitor stem cells (Fig. S4a). Capillary sequencing of RT-PCR products confirmed the predicted splice junctions of ALT and FL transcripts (Fig. S4b). Notably, this alternative splice site was only present in apes and not conserved in other primates, as a single nucleotide substitution at this site results in a derived allele that creates a consensus splice site sequence (Fig. S4c). Experimentally, RT-PCR of plk4 in other vertebrates detected only one transcript establishing that alternative splicing of this region of exon 5 was specific to humans and apes (Fig. 2d).

The identification of an alternative transcript containing an internal 60 aa deletion that lay outside a known functional domain suggested that the 5 bp deletion would lead to reduced PLK4 activity rather than complete loss of PLK4 function. To address this, we first investigated the effect of this mutation on transcript levels by quantitative RT-PCR of PLK4(ALT) and PLK4(FL). As anticipated, PLK4(FL) transcript levels were substantially reduced (Fig. S5a), consistent with nonsense-mediated decay of the prematurely terminating transcript. In contrast, PLK4(ALT) was stably expressed in patient cells (Fig. S5b), such that the total amount of PLK4 transcript available to produce functional PLK4 enzyme in patient cells is reduced to 25.7 +/− 2.8% of control levels (Fig. 2e).

We next determined the consequences of Arg936Serfs*1 and Phe433Leufs*6 mutation on PLK4 protein in three patient cell lines. Western immunoblotting was performed to characterize the effects of the mutations on cellular levels of PLK4 protein. Two PLK4-specific bands were evident on immunoblotting with a published PLK4 antibody18 (Fig. 2f), corresponding to the FL and ALT isoforms. In the P6 and P7 fibroblasts the slower migrating band was absent, consistent with loss of the FL isoform from these cells. P1 fibroblast band intensity was markedly reduced, and appeared to have increased mobility relative to the FL band, in keeping with reduced protein size from the C-terminal truncation. Additionally, PLK4 accumulation at the centrosome was measured by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2g, Fig. S7). As the immunofluorescence signal in primary fibroblasts was too weak to quantify, cells were treated with the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 prior to fixation to enhance PLK4 detection, permitting robust, reproducible measurements. Quantitative analysis of the immunofluorescent signal established that PLK4 levels were significantly reduced (p<0.0001) with PLK4 protein levels 15+/− 0.02 %, 36 +/− 1 % and 42 +/− 0.08 % of control levels in P1, P6, P7 patient fibroblasts, respectively (Fig. 2g).

We concluded that both mutations results in reduced levels of PLK4 protein in the cell. For the Phe433Leufs*6 mutation (P6, P7) this occurs as the consequence of nonsense mediated decay of the FL transcript and consequent loss of the FL protein. For the Arg936Serfs*1 mutation (P1), the frameshift occurs in the terminal exon, so nonsense mediated decay would not be expected. However, structural modelling of the terminal polo-box domain (PB3) indicates that this domain is substantially disrupted (Fig. S3b). Therefore, the marked reduction of protein levels is likely due to consequent reduction in protein stability.

PLK4 mutations impair centriole biogenesis

Functional activity of both full length isoforms and mutant PLK4 proteins were assessed using an overexpression assay 19. Enzyme activity, determined by the over-duplication of centriole number, was significantly impaired for both mutant proteins, indicating that such residual mutant protein would also be functionally impaired (Fig. 3a,b and Fig. S8) In contrast, the PLK4(ALT) protein was as active as PLK4(FL), consistent with similar functionality in centriole duplication.

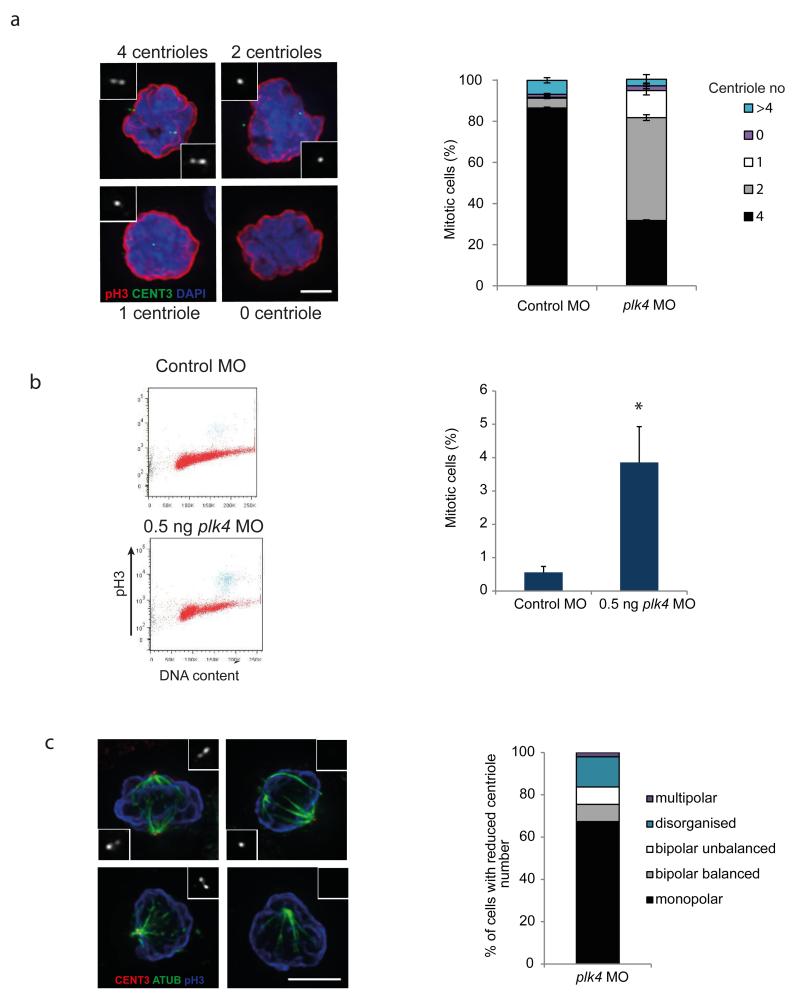

Figure 3. PLK4 mutations impair PLK4 activity in centriole biogenesis, resulting in reduced centriole number in patient cells.

a,b) Centriole over duplication assay demonstrating that transfected FL and ALT PLK4 GFP-tagged constructs are competent for centriole duplication, while F433Lfs*6 and R936Sfs*1 have significantly reduced activity. a) representative images of Hela cells transfected for 48 hr with eGFP PLK4 constructs (immunoblot, Fig. S8) demonstrating centriole over duplication with FL and ALT, but not with truncated gene constructs representing patient mutations. Scale bar=4μm. b) Quantitation of experiments depicted in (i). n=100 cells /exp, exp=3, two tailed t-test *** p≤0.001

c,d) 6-12% of PLK4 patient fibroblasts have reduced centriole number at mitosis. c) Centrin foci quantified in prometaphase and metaphase fibroblasts (exp=3, n>200 cells/ exp). d) Quantification of centriole phenotypes observed in the 12% of mitotic P6 fibroblasts with reduced centriole number (fibroblasts with ≤2 centrioles (exp=3, n>175 cells). ‘2 together’ indicates 2 centrioles detected at one spindle pole, ‘2 separate’ indicates 2 centrioles detected, one at each pole.

e) Mitotic spindle formation is impaired in PLK4 patient P6 fibroblasts with reduced centriole number. Left panel, representative images. Insets of centrin-3 staining are shown at 3 x magnification. ‘balanced’ cells, broad based bipolar spindle; ‘unbalanced’, unequal bipolar spindle; ‘monopolar’, only one spindle pole; ‘disorganised’, failure to establish a spindle pole. ATUB, α-tubulin. Scale bars=10μm. Right panel, quantification of the mitotic spindle phenotypes observed in the 12% of mitotic P6 fibroblasts with reduced centriole number (exp=3, n=75). Error bars, s.e.m. P value, two tailed t-test** ≤0.01, *≤0.05.

Given the transcriptional and protein consequences of the mutations, centriole duplication would be predicted to be impaired but not lost in patient cells. As centriole number changes during the cell cycle, mitosis provides a convenient stage to quantify centriole number, with four centrioles normally present at this time. In keeping with reduced PLK4 function, patient fibroblasts had a statistically significant reduction in centriole number, with the number of prometaphase and metaphase cells containing fewer centrioles (two or less centrin foci) significantly increased compared to two control lines (Fig. 3c, P1, 12% (t-test, p=0.04); P6, 10.2% of cells (t-test, p=0.0004); P7, 5.8%, (p=0.04)). Further characterisation of the centriolar phenotype in mitotic cells from P6 established that cells with reduced centriole number predominantly had a single centriole pair (60%) or were cells with no centriole (25%) (Fig. 3d).

As centrioles are key centrosomal components, centriolar depletion would be expected to impair mitotic spindle formation. Accordingly, normal mitotic spindle formation was affected in patient cells with reduced centriole number, with monopolar spindles most frequently observed (Fig. 3e). Delayed mitotic progression would therefore be predicted in these cells as a balanced bipolar spindle is required for efficient mitosis20. At least some of these cells eventually progress through mitosis as both anaphase cells with a single centriole pair were observed (data not shown) and an increase in interphase cells without centrioles were seen (Fig. S9, P6: 3.9% p=0.03 and P7: 2.5% p=0.01). Mitotic spindle abnormalities can lead to mitotic errors, including chromosome segregation defects, cytokinesis failure, or cell death. However, no significant increase in cells with >4N DNA content was observed by FACS analysis (data not shown) nor was increased cell death detected by Annexin V staining (Fig. S10). Additionally chromosome segregation errors during anaphase were rarely observed (Table S2) and interphase FISH also did not demonstrate a significant increase in aneuploidy or tetraploidy (Fig. S11).

We therefore concluded that reduced PLK4 activity results in impaired centriolar duplication and leads to impaired mitotic spindle formation in a subset of cells. To address the developmental consequences of such cellular PLK4 dysfunction we next established a zebrafish model.

plk4 depletion impairs mitosis and reduces zebrafish size

As our cellular studies established that mutations reduced PLK4 levels, morpholino (MO) antisense oligonucleotides were used to deplete plk4 in zebrafish, a system previously used to model primordial dwarfism due to mutations in ORC121. Splice site-blocking MOs were designed to target splice donor and acceptor sites of exon 5 of zebrafish plk4 (Fig. 4a). Titration of pooled MO oligonucleotides injected into 1-cell stage embryos permitted depletion of plk4 transcript to 2-25% of control levels in 1 day post-fertilization (dpf) embryos (Fig. 4b), with 0.5 ng plk4 MO achieving transcript levels comparable to that seen in PLK4 patient fibroblasts (Fig. 2e). Overall body size was significantly reduced in 5 dpf plk4 morphants (Fig. 4c), with reduction in size correlating with level of transcript depletion (Fig. 4d). Reduction in embryo size was a consequence of reduced cell number (Fig. 4e), with cell size remaining unchanged (Fig. S12). Such reduction in cell number was evident from early on in development (Fig. 4e), and could be the consequence of reduced cell proliferation or increased cell death. Reduced growth was a direct effect of plk4 depletion rather than MO toxicity, as growth was rescued by co-injection of 150 pg of plk4 mRNA with 1.5 ng plk4 MO (p < 0.05, Fig. 4d). Co-injection of human PLK4(FL) and PLK4(ALT) mRNA both partially rescued the dwarfism phenotype indicating that both isoforms can functionally contribute to organism growth (Fig. 4f), while both the Arg936fs*1 and Phe433Leufs*6 mutant forms of PLK4 did not rescue.

Figure 4. Depletion of plk4 causes dwarfism in zebrafish.

a) Schematic of intron-exon structure of zebrafish plk4. Red bars indicate splice sites targeted by morpholino oligonucleotides (MO). RT-PCR primers (arrows).

b) Dose dependent depletion of transcript levels in plk4 morphants. Transcript levels measured by quantitative RT-PCR of RNA extracted at 2 dpf. Transcript levels relative to 2 dpf control MO injected embryos (exp=3; error bars, s.e.m).

c) Depletion of plk4 with 0.5 ng pooled MOs, results in small, morphologically normal, ‘dwarf’ zebrafish. Representative images of embryos at 5 dpf injected with either 0.5 ng plk4 MOs or 12 ng of control MO.

d) Body surface area is significantly reduced in zebrafish injected with plk4 MO, at 5 dpf. Size can be rescued by coinjection of zebrafish (dr) plk4. Surface area expressed as a z-score relative to uninjected embryos of the same age (z-score defined as the standard deviations from the mean for uninjected embryo size at 5 dpf). P value, two-tailed t-test, ***≤0.001, versus control embryos; for RNA-coinjection rescue experiments, versus 1.5 ng plk4 MO alone. Error bars, s.e.m.

e) Cell number is reduced in plk4 morphants. Time course from 0.5 - 48 hpf for plk4 MO concentrations as indicated. Error bars, s.e.m.

f) Wild-type human PLK4 mRNA also partially rescues the growth phenotype, while mRNA encoding truncated protein products representing human mutations F433Lfs*6 and R936Sfs*1 do not complement the growth phenotype. n>50 embryos per experimental condition. exp =1. p value, two-tailed t-test. ** ≤0.01, *≤0.05, versus 1.5 ng plk4 MO alone. Error bars, s.e.m.

To gain insight into the mechanism underlying reduced growth and cell number, plk4 MO injected zebrafish embryos were disaggregated and embryonic cells examined by immunofluorescence and FACS. Centrin 3 immunostaining established that reduced plk4 levels also impaired centriolar biogenesis during development, with the majority of mitotic cells having less than the expected 4 centrioles (Fig. 5a, 65% plk4 morphants versus 7% in control embryos, p=0.0004). We postulated that cell cycle progression would consequently be impaired so next performed cell cycle FACS which demonstrated a significant accumulation of phospho-histone H3 (pH3) positive cells in plk4 morphants (Fig. 5b, 3.9% versus controls <0.56%, p<0.05). Given the reduced cell proliferation in plk4 morphants (Fig. 4e) this indicated a substantial delay in mitotic progression, also seen in stil mutant zebrafish22, likely as the consequence of aberrant mitotic spindle formation (Fig. 5c) resulting from impaired centriole duplication. Spindle formation may additionally be compromised due to the role of Plk4 in acentriolar spindle formation23.

Figure 5. Impaired mitosis leads to growth retardation in plk4 morphant zebrafish.

a) Centriole number is reduced in mitotic cells from plk4 morphants. Left, representative images of mitotic cells from 2 dpf embryos injected with control or plk4 MO. CENT3, centrin-3, pH3, phospho-Histone H3, marker of mitotic chromatin. Right, quantification of centrin-3 foci in 2 dpf zebrafish cells isolated from control MO or dwarf plk4 zebrafish (exp=2, n >100 mitoses/exp, error bars, s.e.m).

b) Increased numbers of mitotic cells are present in 2 dpf zebrafish injected with 0.5 ng plk4 MO. Left, representative FACS plot of DNA content versus pH3 staining of single cell suspension from 2 dpf embryos Mitotic cells have 4N content and are pH3 positive (highlighted in blue). Sub-G1 cells (black). Right, quantification of 3 experiments (n=50 embryos/exp; error bars, s.e.m).

c) Aberrant mitotic spindles are frequently seen in 2 dpf plk4 morphant embryos. Left, insets of centrin 3 staining are shown at 3x magnification. ATUB, α-tubulin. Scale bar, 5 μm. Right, quantification of mitotic phenotypes observed in plk4 morphant embryos with reduced centriole number (exp=1, n=50, error bars, s.d).

Increased apoptosis has been observed in other centriole biogenesis mutants22,24-26, and therefore TUNEL staining was also performed (Fig. S14). A low level of apoptosis was seen in 0.5 ng plk4 MO fish, which increased at higher doses of morpholino suggesting that cell death also contributes to the decrease in cell number, although TUNEL positive cells were often localized to the tail region and did not precisely correlate with the broad increase in pH3 stained cells. Furthermore, unlike the partial rescue seen in stil mutant zebrafish with tp53 depletion22, no rescue in growth was seen in plk4 morphant zebrafish (Fig. S15).

Photoreceptor and ciliopathy phenotypes in plk4 embryos

Retinopathy occurs in patients with both PLK4 and TUBGCP6 mutations (Table 1) and so we next utilised our plk4 morphant model to investigate the basis of this phenotype. Plk4 morphant zebrafish had impaired responses to visual stimuli, with 60% having impaired dark-light adaption even at low (0.5 ng) MO levels (Fig. 6a). Immunohistological examination of the eyes demonstrated loss of photoreceptors, using the marker zpr-127, as well as a variable reduction in eye size (Fig. 6b), consistent with the ophthalmological findings observed in PLK4 and TUBGCP6 patients. As cilia are key structures in the photoreceptors required for outer segment structure and function28, immunostaining of cilia axonemes and basal bodies was performed (Fig. 6c, Fig. S16). This demonstrated reduced numbers of cells containing cilia in the photoreceptor layer, with absence of basal bodies correlating with absence of cilia. Cilia loss was a direct rather than toxic effect of plk4 MO as it could be rescued by co-injection of PLK4 mRNA (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6. plk4 morphant zebrafish display retinal defects due to reduced cilia number.

a) plk4 morphant zebrafish exhibit an impaired vision-dependent response, with reduced melanocyte constriction upon exposure to light. Left, representative images of melanocytes on the dorsal aspect of 5 dpf zebrafish in dark and light adapted conditions. Right, quantification of light adaptation using 0.5 – 3 ng plk4 MO at 5 dpf, exp=2 n> 50 embryos/exp. Error bars, s.e.m.

b) Photoreceptor number is reduced in plk4 morphants. Confocal optical sections of 5 dpf zebrafish retina from plk4 and control morphants stained with zpf-1 (photoreceptors, black) and DAPI (grey). Eye size is also reduced in plk4 morphants at higher doses, while size reduction is variably present at the 0.5 ng dose (2 representative images shown at this dose).

c) Cilia numbers are reduced in the photoreceptor layer of the retina in a dose-dependent manner in plk4 morphants and can be rescued by co-injection of PLK4 mRNA. Optical sections of 5 dpf zebrafish retina and higher magnification of photoreceptor cells (boxed region) below and right panels. zpr-1 (photoreceptors, green); AcTubulin, acetylated-tubulin (cilia axonemes, red), DAPI (white). ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer.

Additional, cilia-related phenotypes were observed on injection of higher doses of plk4 MO oligonucleotides, as previously observed with cep152 depleted zebrafish29. Notably, these were separable from the growth phenotype in a dose-dependent manner; with 0.5 ng plk4 MO injections resulting in small but structurally normal fish, while at 1.5 ng and 3 ng, embryos with ciliopathy-associated phenotypes were generated, including hydrocephalus, renal cysts and ventral curvature (Fig. 7a-d). Furthermore, left-right asymmetry defects were detectable on injecting plk4 MO into a transgenic reporter line (bre:egfp) that labels heart musculature (Fig. 7c) and quantification of motile cilia in the Kuppfer’s vesicle demonstrated a significant decrease in the proportion of cells with cilia in embryos injected with 3 ng plk4 MO (Fig. 7d). Likewise the number of ciliated cells was also decreased in serum-starved patient fibroblasts (Fig. S17). As many cells in plk4 MO embryos had no remaining centrioles (25% 0 centrioles, 38% 1 centriole, 30% 2 centrioles), and cilia loss correlated with basal body absence in patient cells, we concluded that the cilia phenotype was likely directly attributable to absence of basal bodies.

Figure 7. Growth failure and ciliopathy phenotypes are separable in a dose dependent manner.

a-d) Morphological ciliopathy phenotypes are evident at higher levels of plk4 depletion. a) 1.5 ng plk4 morphants at 5 dpf exhibit ciliopathy phenotypes, including dilated brain ventricles (arrow), pronephric duct cysts (arrow head) and ventral body axis curvature. b) Penetrance of ciliopathic phenotypes (scored by presence of ventral curvature) in 2 dpf plk4 morphant embryos injected with 0.5 – 3ng MO. c) Heart laterality defects are observed at 3 dpf in Tg(bre:egfp) zebrafish embryos injected with 3 ng plk4 MO, with loss of asymmetry (midline) or inversion of ventricle-atrium asymmetry (reversed) (A, atrium; V, ventricle). Right, quantification of heart laterality defects (exp=2, n>40 embryos).

d) The proportion of ciliated cells is reduced in the Kupffer’s vesicles of 3 ng plk4 morphants. Left, representative images from control and 3 ng plk4 morphants at 16 hpf. aPKC, atypical protein kinase C (Kupffer’s vesicle marker, green); Ac-tubulin, acetylated tubulin, cilia (red). Right, quantification of cells ciliated in the Kupffer’s vesicle.

e,f) Model of disease pathogenicity. e) Autoregulation of Plk4 results in a narrow window in which mutations impair enzymatic activity without resulting in embryonic lethality. At 50% transcript levels protein levels are normal34. Further depletion of PLK4, as seen in PLK4 patients, leads to protein loss and growth defects. Additional loss of cellular PLK4 activity results in cilia-related phenotypes. f) Centriole duplication becomes inefficient at reduced PLK4 levels, with reduced centriole number impairing mitotic spindle formation and cell cycle progression. With severe reduction in PLK4 activity, cells completely lacking centrioles are generated, which are unable to form cilia, leading to ciliopathy phenotypes.

Discussion

Here we identify mutations in PLK4 and TUBGCP6 in microcephalic dwarfism and using cellular and developmental systems establish that through reduction in centriole number, PLK4 mutations result in growth and retinal phenotypes.

The microcephaly and short stature seen in PLK4 and TUBGCP6 patients is comparable to that seen with previously reported centriolar biogenesis genes8-11. However, additional developmental anomalies are also apparent, most prominently a generalised retinopathy that has not been reported with other primary microcephaly/Seckel syndrome genes. While a consistent feature in TUBGCP6 patients, it remains to be established if retinopathy is an invariant feature of PLK4 mutations, as geographical remoteness of Families 1 and 3 precluded detailed ophthalmological assessment and electroretinography. Mutations in the mitotic spindle binding motor kinesin, KIF11, also cause microcephaly and retinopathy, but this phenotype is dominantly inherited, manifesting as chorioretinopathy and retinal folds30, seemingly distinct from the retinopathy reported here. TUBGCP6 is a direct phosphorylation target of PLK4, so this may define a new pathway with specialised function in photoreceptors. Alternatively, the retinal pathology may result from perturbed mitosis in the eye31, or as a consequence of impaired cilia formation given the loss of photoreceptor cilia in the plk4 zebrafish model.

Although the biology of Plk4 has been intensively studied in recent years32, the early embryonic lethality of the Plk4−/− mouse17 has limited developmental studies in mammals. Haploinsufficient Plk4+/− mice have not been reported to have microcephaly or reduced body size, but were found to exhibit increased rates of liver and lung cancer33. Although increased genome instability was thought to be due to cellular centrosome amplification and increased levels of tetraploidy, more recent studies on the same Plk4+/− embryonic fibroblasts failed to demonstrate centrosome amplification or aneuploidy34. Additionally, centrosomal Plk4 protein levels were normal, despite a 50% decrease in transcript levels in Plk4+/− cells, explained by the ability of PLK4 to regulate its own stability through auto-phosphorylation of a phosphodegron35. In contrast, in PLK4 patient cells a more substantial decrease in transcript levels (75%) impairs protein function, resulting in reduced centriole duplication. Therefore, human PLK4 mutations appear to fall into a narrow window where autoregulation fails to fully compensate, but sufficient enzyme activity remains to prevent lethality (Model, Fig. 7e).

A single pair of centrioles at one spindle pole is most frequently seen in mitotic PLK4 patient cells, suggesting that when centriole duplication fails the centrosome remains a highly stable structure. Acting as a single microtubular organising centre this results in a monopolar spindle12, delaying mitotic progression. Such a configuration may be more challenging for mitosis even than acentriolar spindle assembly, however such mitoses can successfully resolve, as patient cells are seen without any centrioles (Fig. S9). This likely occurs by eventual formation of a bipolar spindle to permit chromosome segregation34. Although only a proportion of mitoses are affected (Fig. 3), during development most patient cells would be expected to encounter monopolar spindle formation at some point over successive rounds of cell divisions. Such a reduction in mitotic and cell cycle efficiency could consequently be sufficient to cause significant dwarfism over the ~46 cell divisions required to produce the 1014 cells of the human body. As mitotic delay can also promote cell death25, this may also contribute to reduced organism size through depletion of cell number. Indeed, p53-mediated apoptosis resulting from mitotic arrest occurs in stil mutant zebrafish and cpap−/− mice22,25. Increased apoptosis is also seen in plk4 embryos, however as plk4 embryo growth was not rescued in tp53 null background, this suggests that additional pathways contribute to cell death in the absence of normal centrosome numbers.

The disproportionate effect of mutations in PLK4, (and other primary microcephaly/ Seckel syndrome centrosomal genes), on brain size remains an important unanswered question, particularly as all are ubiquitously required for cell division. It may be that the specific requirement for coordination of symmetric and asymmetric cell divisions in neural progenitor cells36 is disrupted in PLK4 patients due to abnormal spindle assembly. Alternatively, mitotic progression may be disproportionately impaired in neuroepithelial tissues 31 given high rates of proliferation in neurogenesis, a process that has a restricted developmental time frame. Thirdly, aberrant mitosis may itself promote cell death within the mammalian brain37. Furthermore, in this respect monopolar spindle formation can predispose to chromosome segregation failure38, and while substantial levels of aneuploidy were not detected in PLK4 patient fibroblasts, microcephaly can result from aneuploidy occurring during neurogenesis39,40.

Cilia phenotypes were only seen in zebrafish with substantial depletion of plk4, accompanied by marked body size reduction. Extrapolating to human development this may explain why cilia and growth defects have not been reported, as more extreme intrauterine growth restriction is unlikely to be viable. Separation of ciliopathic and growth phenotypes is likely explained by the different sensitivity of mitosis and ciliogenesis to impaired centriole duplication. Reduced centriole number will result in monopolar spindle formation, disrupting mitosis, while ciliogenesis may continue, with cilia loss only occurring when no centrioles remain, as a single centriole may be sufficient to generate cilia41. However, many mitoses in PLK4 patient cells have 2 centrioles at one pole and none at the other, and therefore it is more likely that the proportion of ciliated cells is reduced in a dose dependent manner, with cilia-dependent phenotypes only appearing when a critical level is reached (Model, Fig. 7f). Some decrease in ciliation of patient fibroblasts is seen, but this appears to be tolerated developmentally as there is a general absence of ciliopathy phenotypes in patients. Notably, a 100-fold reduction in cilia is needed to impair nodal flow and perturb L-R asymmetry in mouse embryos42, demonstrating that developmental processes can be highly tolerant of reduced cilia number.

Given the essential role of centrioles during mammalian development24 the presence of truncating mutations in centriole biogenesis genes8-11 is therefore surprising. Our identification of an alternative isoform that partially rescues PLK4 activity in the face of an intragenic frameshift deletion reconciles this disparity at least for this gene. It will be of interest to determine how centriole duplication is maintained with null mutations in other centriolar biogenesis genes.

In summary, we report that mutations in PLK4 and TUBGCP6 cause microcephalic primordial dwarfism and a generalised retinopathy, extending the phenotype-spectrum associated with centriole biogenesis genes, identifying a new biological pathway for retinal dysfunction and establishing that PLK4 activity is differentially required for growth and cilia-dependent processes during development.

Online Materials and methods

Research subjects

Genomic DNA from the affected children and family members was extracted from peripheral blood by standard methods or saliva samples using Oragene collection kits according to manufacturer’s instructions. Informed consent was obtained from all participating families and the studies were approved by the ethics review board at the National Institute for Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering in Faisalabad and the Scottish Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (04:MRE00/19). Parents provided written consent for the publication of photographs of the patients.

Exome capture and sequencing

Whole exome capture and sequencing was performed at the Cologne Center for Genomics (CCG) and at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI), UK. At the WTSI, DNA was sheared to 150 bp lengths by sonification (Covaris) prior to whole exome capture and amplification using the SureSelect Human All Exon 50 Mb kit (Agilent). Fragments were sequenced using an IlluminaHiSeq. 75 bp paired end sequence reads were aligned to the Genome Reference Consortium human build 37 reference sequence using BWA43. Single nucleotide variants were called using GenomeAnalysisTK and SAMtools whilst Indels were called using Dindel and SAMtools. Variants were then annotated with functional consequence using Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor44. Allele frequencies from the 1000 genomes44 database were used for filtering of population variants. Datasets were analysed under a mode of autosomal recessive inheritance. At the CCG, we fragmented 1 μg of DNA using sonification technology (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA). Fragments were enriched using the SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v2.0 kit (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI, USA) and subsequently sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing instrument using a paired end 2 × 100 bp protocol. This resulted in 8.4 Gb of mapped sequences, a mean coverage of 89-fold, a 30x coverage of 87%, and a 10x coverage of 97% of target sequences. For data analysis, the Varbank pipeline v.2.3 and filter interface was used. Primary data were filtered according to signal purity by the Illumina Realtime Analysis (RTA) software v1.8. Subsequently, the reads were mapped to the human genome reference build hg19 using the BWA43 alignment algorithm. GATK v1.645 was used to mark duplicated reads, to do a local realignment around short insertion and deletions, to recalibrate the base quality scores and to call SNPs and short indels.

Scripts developed in-house at the CCG were applied to detect protein changes, affected donor and acceptor splice sites, and overlaps with known variants. Acceptor and donor splice site mutations were analysed with a Maximum Entropy model46 and filtered for effect changes. In particular, we filtered for high-quality (coverage >15; quality >25) rare (MAF<0.005) homozygous variants (dbSNP build 135, the 1000 Genomes database build 20110521, and the public Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project, Seattle, build ESP6500). We also filtered against an in-house database containing variants from 511 exomes from epilepsy patients to exclude pipeline related artefacts (MAF<0.004). We validated variants of highest priority by conventional Sanger sequencing.

Capillary sequencing

Primers were designed to amplify all exons and exon/intron boundaries of PLK4 and TUBGCP6 (Table S3a). Genomic DNA from patients and parents (when available) was amplified and PCRs capillary sequenced on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer. Sequence traces were analyzed using Mutation Surveyor software (SoftGenetics Inc.).

SNP and Microsatellite genotyping

Eight individuals of family 1 from Pakistan were genotyped on an Illumina HumanCoreExome-12 v1.1 BeadChip (Fig. S1, IV-1 (MCP68-5), IV-16 (MCP68-7), IV-17 (MCP68-9), V-1 (MCP68-13), V-2 (MCP68-14), V-3 (MCVP68-10), VI-2 (MCP68-11), VI-1 (MCP68-12). Genome-wide linkage analysis of the family was performed with 24,209 selected SNP markers. LOD scores were calculated with ALLEGRO47. Data handling, evaluation, and statistical analysis were performed as described previously48.

Microsatellites present within a 14.2 Mb region flanking PLK4 were identified from public sequence databases, amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using fluorescently labelled primers (primer sequences in Table S3b) and genotyped on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer.

Plasmid constructs

The zebrafish plk4 expression construct was generated by PCR amplification of full-length plk4 from 5 hpf zebrafish embryo cDNA, followed by TA cloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega). Full-length human PLK4 was generated by PCR amplification of PLK4 from IRATp970C1132D plasmid (Source Bioscience), PLK4 c.2811-5C>G, PLK4 c.1299_1303delTAAAG and PLK4(ALT) were generated from the full-length clone using PCR amplification. PCR fragments were then shuttled into pDEST-EGFP (LMBP 4542) and pCDNA3.1-MYCHIS-DEST using Gateway cloning (Life technologies). Capped plk4 mRNA for injection was transcribed in vitro from linearized DNA using the MessageMachine Transcription kit (Ambion) and purified using the MEGAclear transcription clean-up kit (Ambion).

RT-PCR

RNA was obtained from human primary fibroblast cell lines, human fetal retina RNA (AmsBio R1244108-10), an African green monkey fibroblast cell line, total bovine brain (AmsBio RIB34035), Madin-Darby canine kidney cell line, total guinea pig (AmsBio GR-201), Chinese hamster ovary cell line, mouse embryonic fibroblast line, chicken B lymphocyte cell line and zebrafish embryos. The FirstChoice®Human total RNA survey panel (Ambion) and Marathon Ready adult retina cDNA (Clontech 639349) were also used as a source of human tissue.

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) or TRIzol (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was eliminated by DNAse I treatment (Qiagen) and cDNA generated using random oligomer primers and AMV RT (Roche). RT-PCR primer pairs utilized in this study are in Table S3c.

Quantitative real time PCR for human and zebrafish transcripts was performed using the Brilliant II Sybr Green qPCR Master Mix (Stratagene) on the ABI Prism HT7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosciences). The relative expression of target genes to a control was calculated using the comparative CT method (2-ΔΔCT) method 49 and represented as fold mRNA induction. qPCR primers used are in Table S3d.

Cell culture

Dermal fibroblasts were obtained by skin punch biopsy and were cultured in amnioMAX C-100 complete medium (Life Technologies) and maintained in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 and 3% O2. HeLa were obtained from European collection of cell cultures (#93021013) cultured in DMEM (Life technologies), 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma. To induce ciliogenesis, cells were incubated in low serum (0.5% FCS) DMEM medium for 48 hrs.

Short interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides were transfected into primary fibroblasts using Dharmafect 1 (Thermo Fischer) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Oligonucleotide sequences used are in Table S3e. PLK4 expression vectors were transfected into HeLa cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Life technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Where indicated, cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 (Cayman Chemicals) or 1.5 μM staurosporine (Alexis Biochemicals) for 5 hrs.

Interphase FISH

Nuclei cell suspensions were made by standard methods from patient fibroblasts incubated in hypotonic buffer (0.25% KCl) prior to fixation with 3:1 v/v methanol:acetic acid. FISH was performed using chromosome 3, 4, 7, 10, 17 and 18 centromere chromosome enumeration (CEP) probes (Abbot Molecular) labelled in Spectrum orange/green/aqua in CEP hybridization buffer. Slides were scanned on the GSL-120 Automated Slide Scanner at 60x magnification and analysed using Cytovision version 7.3.1 (Leica Biosystems).

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

Primary fibroblasts were grown on untreated coverslips. Zebrafish embryo cells were adhered to poly-L-lysine coated coverslips (Becton Dickinson). Cells were either fixed in −20°C methanol for 7 min or 4% PFA (TAAB) in PHEM (25 mM Hepes-NaOH pH 6.8, 100 mM EGTA, 60 mM PIPES, 2 mM MgCl2) for 15 min. Following PFA fixation, cells were permeabilised by treatment in 0.2% triton-X-100 in PHEM for 2 min. Fixed cells were blocked in PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich). Primary antibodies used were: γ-tubulin (Sigma T5192), α- Tubulin (Sigma T6074), PLK418, Centrin 2 (Santa Cruz SC27793), Centrin 3 (Novus Biologicals H00001070-M01), phosphorylated serine 10 histone 3 (Cell Signalling 9701), glutamylated tubulin50, adenylate cyclase III (Santa Cruz SC32113), IFT88 (Proteintech 13967-1-AP) and IFT140 (Proteintech 17460-1-AP). Secondary antibodies used were anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 linked (Life Technologies A11029), anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 568 linked (Life Technologies A11036). Imaging was performed using an Axioplan 2 widefield fluorescence microscope (Zeiss) controlling a CoolSnap camera (Roper Scientific). Images were captured using a 100 X Plan-APOCHROMAT (1.4 NA) objective at 0.2 μm z-sections and subsequently deconvolved using Volocity software (PerkinElmer). For centriole scoring, when 3 centrin signals were seen, these were binned with the 4 centrin signal counts, as normal centriole number can sometimes only be resolved into 3 signals by conventional light microscopy due to limited spatial resolution10. Fluorescence intensity analysis of 3D datasets was performed using Volocity. A region covering each centrosome was defined in a 3D dataset and the signal through all the sections was summed. Intensity values for a cytoplasmic background of matched volume were obtained and subtracted from the centrosome signal.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in 50 mMTris-HCl, pH8, 280 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA and 10% glycerol supplemented with protease inhibitor tablet (Roche). Protein samples were run on a 6/12% acrylamide gel followed by immunoblotting using anti-PLK4 and anti-actin antibodies (Sigma A2066).

Zebrafish studies

Adult male and female (<18 months age) wild-type (AB Tübingen) and transgenic zebrafish (Danio rerio) strains were maintained under standard laboratory conditions on a 14 hr light /10 hr dark cycle at 28°C. Experiments were performed in compliance with ethical regulations under Home Office licence PL 60/4418. Adult pairs were used to generate embryos 0-5 dpf, with embryos from the same pair used both for control and plk4 morpholino injections. Embryos were staged according to Kimmel51. plk4 knockdown was performed using sequence-specific antisense morpholino oligos (MOs) (Gene Tools). A volume of 1.5 nl containing 0.5 ng, 1.5 ng, or 3 ng were microinjected in into one-cell stage embryos of wild-type (AB) zebrafish strains. Morpholino sequences used are in table S3f. plk4 mRNA was co-injected for rescue at a final concentration of 150 pg in 1.5 nl. Live zebrafish were imaged on a Nikon AZ100 Macrosope using iVision software (BioVision Technologies), and body surface area was calculated using ImageJ (NIH) software.

For whole mount immunostaining, zebrafish embryos were fixed in 4% PFA (TAAB) in 0.1% Tween 20/PBS overnight at 4°C, then dehydrated or stored in methanol at −20°C. To stain the Kupffer’s vesicle the embryos were manually dechorionated and the yolk removed. For imaging of the photoreceptor cells, eyes were removed after whole mount staining and mounted in Vectashield (Vectorlabs H-1000). Primary antibodies used were: zpr-1 (Abcam ab174435), acetylated tubulin (Sigma 6-11B-1), aPKC (Santa Cruz SC216), γ-tubulin (Sigma T5192) and phospho histone 3 (Merck Millipore MABE13). Apoptosis was determined by TUNEL staining using the Apoptag TUNEL Kit (Millipore, S7100) with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-Digoxygenin antibody (Roche, 11093274910). TUNEL stained embryos were imaged in Glycerol on a Nikon AZ100 Macrosope using iVision software (BioVision Technologies). pH3 stained embryos were imaged on an Axioplan 2 widefield fluorescence microscope (Zeiss) controlling a CoolSnap camera (Roper Scientific) with 5x magnification. All other imaging of embryos was performed on a confocal laser microscope (Nikon A1R) using NIS-elements software (Nikon Instruments). Images were captured using 10x air and 60x oil immersion objectives. Experiments were neither randomized nor were investigators blinded to the mRNA or morpholinos used, except for embryo size measurements where images were coded and surface area determined blind. Sample sizes were chosen empirically, without statistical power calculation, with typically 50 embryos used per experimental condition. Non-viable embryos were excluded from analysis.

Zebrafish cell counts

Embryo dissociation into single cells was adapted from the Lawson Lab’s protocol. Briefly, embryos were dissociated by pipetting in Ca2+ -free Ringer’s solution and trypsinised for 15 min in a 1:1 trypsine:versene solution at 29°C. For the dissociation of embryos older than 6 hpf collagenase P (Roche) was added to the trypsin solution. After passaging through a 40 μm mesh, cells were centrifuged at 350 g. After resuspension in phenol red–free medium, cells were counted using the MOXI (z) cell counter (Orflo).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

For FACS analysis, embryos were dechorionised with Pronase (2 mg/ml), dissociated into a single cell suspension (as described for cell counting) and fixed in 4% PFA. Mitotic cells were then labelled with pH3 antibody (Millipore #06-570) and DNA content was assessed by propidium iodide (PI, 50 μg/ml). Apoptotic cells were labelled live with annexin-V (Life technologies A13201) and PI (3.5 μg/ml) as a counter stain to identify viable cells. Cells were sorted on a BD Biosciences FACSAriaII and data analyzed using FlowJo software (v7.6.1, Tree Star).

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as averages, with variance either as s.e.m or s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (Graphpad Software Inc.). For all quantitative measurements, normal distribution was assumed, with t-tests performed, unpaired and two-sided unless otherwise stated. For categorical data, Χ2-test was used. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind, as the different conditions were clearly recognizable by the experimenter, aside from zebrafish surface area determination as described above. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, which were determined empirically from previous experimental experience with similar assays, and/or from sizes generally employed in the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the families and clinicians for their involvement and participation; P.Mills, T.Hurd, M.Bettencourt-Dias and M.Reijns for commenting on the manuscript; N.Hastie, D. Fitzpatrick, and J.Livingston for helpful discussions; C. Janke for his kind gift of the GT335 antibody; E.Freyer for assistance with FACs analysis; P.Gautier for bioinformatics, P.Carroll and A. Garner for technical assistance; IGMM core sequencing service; IGMM imaging facility for assistance with microscopy; E.Patton and the IGMM fish facility for advice and zebrafish technical assistance. E. Liston and the DNA Resource Centre at SickKids for sample processing. A.Pearce and E.Maher, Cytogenetics lab, SE Scotland Genetics Service, for technical advice. Doctor Gabriele Hahn from the University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden, for her second opinion on the MRI data, as well as to Nina Dalibor and Elisabeth Kirst from the CCG for their expert technical assistance. This work was supported by funding from the MRC, Lister Institute for Preventative Medicine and ERC (APJ), Medical Research Scotland (LSB), National Institute for Health Research Moorfields Eye Hospital Biomedical Research Centre (ATM), Köln Fortune (MSH), and CMMC (PN, AAN).

Footnotes

URLs

GenomeAnalysisTK, http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/; SAMtools, http://www.samtools.sourceforge.net/; Dindel http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/dindel/; Varbank pipeline v.2.3, http://www.varbank.ccg.uni-koeln.de/. Lawson lab’s protocol, http://lawsonlab.umassmed.edu/reagents.html/.

References

- 1.Nigg EA, Raff JW. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009;139:663–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettencourt-Dias M, Hildebrandt F, Pellman D, Woods G, Godinho SA. Centrosomes and cilia in human disease. Trends Genet. 2011;27:307–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sir JH, et al. Loss of centrioles causes chromosomal instability in vertebrate somatic cells. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:747–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201309038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, Pellman D. A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature. 2009;460:278–82. doi: 10.1038/nature08136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonczy P. Towards a molecular architecture of centriole assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:425–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guernsey DL, et al. Mutations in centrosomal protein CEP152 in primary microcephaly families linked to MCPH4. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalay E, et al. CEP152 is a genome maintenance protein disrupted in Seckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;43:23–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond J, et al. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat Genet. 2005;37:353–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A, Girimaji SC, Duvvari MR, Blanton SH. Mutations in STIL, encoding a pericentriolar and centrosomal protein, cause primary microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:286–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sir JH, et al. A primary microcephaly protein complex forms a ring around parental centrioles. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1147–53. doi: 10.1038/ng.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain MS, et al. A truncating mutation of CEP135 causes primary microcephaly and disturbed centrosomal function. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:871–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bettencourt-Dias M, et al. SAK/PLK4 is required for centriole duplication and flagella development. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Wilkinson CJ, Nigg EA. The Polo kinase Plk4 functions in centriole duplication. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1140–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verloes A, Drunat S, Gressens P, Passemard S. Primary Autosomal Recessive Microcephalies and Seckel Syndrome Spectrum Disorders. In: Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R) Seattle (WA): 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahtz R, et al. GCP6 is a substrate of Plk4 and required for centriole duplication. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:486–96. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puffenberger EG, et al. Genetic mapping and exome sequencing identify variants associated with five novel diseases. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson JW, et al. Late mitotic failure in mice lacking Sak, a polo-like kinase. Curr Biol. 2001;11:441–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cizmecioglu O, et al. Cep152 acts as a scaffold for recruitment of Plk4 and CPAP to the centrosome. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:731–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleylein-Sohn J, et al. Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev Cell. 2007;13:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hornick JE, et al. Amphiastral mitotic spindle assembly in vertebrate cells lacking centrosomes. Curr Biol. 2011;21:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bicknell LS, et al. Mutations in ORC1, encoding the largest subunit of the origin recognition complex, cause microcephalic primordial dwarfism resembling Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Nat Genet. 2011;43:350–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaff KL, et al. The zebra fish cassiopeia mutant reveals that SIL is required for mitotic spindle organization. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5887–97. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00175-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coelho PA, et al. Spindle formation in the mouse embryo requires plk4 in the absence of centrioles. Dev Cell. 2013;27:586–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Izraeli S, et al. The SIL gene is required for mouse embryonic axial development and left-right specification. Nature. 1999;399:691–4. doi: 10.1038/21429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bazzi H, Anderson KV. Acentriolar mitosis activates a p53-dependent apoptosis pathway in the mouse embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E1491–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400568111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIntyre RE, et al. Disruption of mouse Cenpj, a regulator of centriole biogenesis, phenocopies Seckel syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larison KD, Bremiller R. Early onset of phenotype and cell patterning in the embryonic zebrafish retina. Development. 1990;109:567–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheway G, Parry DA, Johnson CA. The role of primary cilia in the development and disease of the retina. Organogenesis. 2013;10 doi: 10.4161/org.26710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blachon S, et al. Drosophila asterless and vertebrate Cep152 Are orthologs essential for centriole duplication. Genetics. 2008;180:2081–94. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.095141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slevin LK, et al. The structure of the plk4 cryptic polo box reveals two tandem polo boxes required for centriole duplication. Structure. 2012;20:1905–17. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novorol C, et al. Microcephaly models in the developing zebrafish retinal neuroepithelium point to an underlying defect in metaphase progression. Open Biol. 2013;3:130065. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sillibourne JE, Bornens M. Polo-like kinase 4: the odd one out of the family. Cell Div. 2010;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko MA, et al. Plk4 haploinsufficiency causes mitotic infidelity and carcinogenesis. Nat Genet. 2005;37:883–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland AJ, et al. Polo-like kinase 4 controls centriole duplication but does not directly regulate cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1838–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holland AJ, Lan W, Niessen S, Hoover H, Cleveland DW. Polo-like kinase 4 kinase activity limits centrosome overduplication by autoregulating its own stability. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:191–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA. Spindle orientation in mammalian cerebral cortical development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:737–46. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JF, et al. Microcephaly disease gene Wdr62 regulates mitotic progression of embryonic neural stem cells and brain size. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3885. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson SL, Compton DA. Examining the link between chromosomal instability and aneuploidy in human cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:665–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marthiens V, et al. Centrosome amplification causes microcephaly. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:731–40. doi: 10.1038/ncb2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanks S, et al. Constitutional aneuploidy and cancer predisposition caused by biallelic mutations in BUB1B. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1159–61. doi: 10.1038/ng1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sorokin SP. Reconstructions of centriole formation and ciliogenesis in mammalian lungs. J Cell Sci. 1968;3:207–30. doi: 10.1242/jcs.3.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinohara K, et al. Two rotating cilia in the node cavity are sufficient to break left-right symmetry in the mouse embryo. Nat Commun. 2012;3:622. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLaren W, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–70. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeo G, Burge CB. Maximum entropy modeling of short sequence motifs with applications to RNA splicing signals. J Comput Biol. 2004;11:377–94. doi: 10.1089/1066527041410418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gudbjartsson DF, Jonasson K, Frigge ML, Kong A. Allegro, a new computer program for multipoint linkage analysis. Nat Genet. 2000;25:12–3. doi: 10.1038/75514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hussain MS, et al. CDK6 associates with the centrosome during mitosis and is mutated in a large Pakistani family with primary microcephaly. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:5199–214. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolff A, et al. Distribution of glutamylated alpha and beta-tubulin in mouse tissues using a specific monoclonal antibody, GT335. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;59:425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.