Abstract

Objective To report the number of participants needed to recruit per baby born to trial staff during AVERT, a large international trial on acute stroke, and to describe trial management consequences.

Design Retrospective observational analysis.

Setting 56 acute stroke hospitals in eight countries.

Participants 1074 trial physiotherapists, nurses, and other clinicians.

Outcome measures Number of babies born during trial recruitment per trial participant recruited.

Results With 198 site recruitment years and 2104 patients recruited during AVERT, 120 babies were born to trial staff. Births led to an estimated 10% loss in time to achieve recruitment. Parental leave was linked to six trial site closures. The number of participants needed to recruit per baby born was 17.5 (95% confidence interval 14.7 to 21.0); additional trial costs associated with each birth were estimated at 5736 Australian dollars on average.

Conclusion The staff absences registered in AVERT owing to parental leave led to delayed trial recruitment and increased costs, and should be considered by trial investigators when planning research and estimating budgets. However, the celebration of new life became a highlight of the annual AVERT collaborators’ meetings and helped maintain a cohesive collaborative group.

Trial registration Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry no 12606000185561.

Disclaimer Participation in a rehabilitation trial does not guarantee successful reproductive activity.

Introduction

Trial governance and good clinical practice dictates detailed gathering of serious adverse events and SUSARs—that is, suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions—in trials. In the large international trial on acute stroke, AVERT (a very early rehabilitation trial), we became aware early on of a particular phenomenon of another SUSAR—special unexpected staff absences registered, owing to babies born to trial clinical staff.

Initially, these events were joyfully communicated to the AVERT collaborators via congratulatory emails and birth notices in the monthly AVERT investigator newsletters (featuring a range of stork Clipart). Inquiries to the site lead investigator followed, to determine recruitment plans of a new team member. However, as these baby related SUSARs accumulated, management tracked these events in detail to assess their effect on trial progress. In this retrospective analysis, we report the frequency of births and the management team’s response to the events; model the effect of babies born on recruitment, staff training, and financial management; and discuss how baby tracking influenced the morale of the study investigators.

Methods

Study design and trial staff

The design and primary results of AVERT, which tested the hypothesis that early and frequent mobility training after a stroke could reduce disability, have been published previously.1 2 3 This pragmatic trial was fully embedded into the acute hospital environment. Typically, sites were publicly funded hospitals. Trial staff included hospital clinicians (physiotherapists and nurses already employed at the site) who delivered the intervention and other hospital staff (clinical or Stroke Research Network employees in the United Kingdom) who recruited patients or provided blinded follow-up of participants. Management was undertaken at the central coordinating office (known as AVERT Central). We provided onsite training at study initiation, repeated as necessary for new trial staff. Annual investigator meetings helped maintain intervention fidelity and foster close communication between site teams and AVERT Central.

Procedures and study data

During the initial (pilot) phase (2006-08), trial staff members informally notified AVERT Central with their birth news. From 2008, more formal methods of case ascertainment were used. We asked trial staff to notify the central coordinating office of any trial parental leave. Additionally, routine reminders to share baby news were made via regular emails, telephone calls, site visits, and monthly newsletters. An updated baby count graph (web appendix 1) was regularly presented at investigators’ meetings, during which the effect on staff morale was determined by a subjective “laughometer.” We maintained a register of all trial staff, their qualifications, and duration of their trial participation. Active months of recruitment for each site and recruitment per month, the total number of staff working on the trial, staff turnover, and the number of site visits required for training new staff were recorded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of trial participants needed to recruit per baby born to trial staff (NNRpB), calculated as the ratio of the total number of patients recruited in AVERT to the number of babies born to trial staff. The secondary outcome was the costs of added recruitment years, reported as total costs and mean costs per birth episode.

Analysis

We grouped countries into three regions: Australia/New Zealand, Asia (Singapore, Malaysia), and the UK (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales). Staff members who took parental leave were included in this analysis. NNRpB measures were reported as ratios with binomial 95% confidence intervals. We compared differences in NNRpB between participating regions using Fisher’s exact test.

To illustrate the effect of the SUSARs, we also present a case study from one foundation site involved since trial commencement. Costs were calculated retrospectively from AVERT Central records, by use of estimated costs for closing and opening new sites (such as site visits, administrative time, and ethical considerations) and additional training time for new staff (including travel costs). Total costs and cost per birth are reported in 2015 Australian dollars ($A).

Patient involvement

A stroke survivor contributed to all stages of the development and the conduct of the AVERT trial as a consumer representative on the trial steering committee, the management committee and on manuscript writing groups. The burden of trial intervention was reported by each patient at the end of each therapy session, however, overall trial burden to patients and family was not evaluated. Biannual trial newsletters have been distributed to patients throughout the trial and patients were invited to describe their experience of stroke and the trial in this newsletter. The trial results will be distributed to participants by hospital trial staff on completion of the trial.

Results

For AVERT, we randomised 2104 participants from 56 sites between 18 July 2006 and 16 October 2014, during a total of 198 recruitment years (calculated as the total time each site was involved in the trial). Of 1074 trial staff registered, 926 were women and 148 were men (man to woman ratio of 1:6.3). These workers included 629 nurses, 284 physiotherapists, 50 occupational therapists, 38 assistant clinicians, three speech and language therapists, one psychologist, and 69 physicians. The median age was 28.0 (interquartile range 24.0-36.8) years.

We were notified of 29 babies born in the pilot phase. A further 91 babies (total n=120) were born to 97 site staff (table 1). Eleven additional babies born to AVERT Central staff were not included in the primary analysis, which focused on the effect of birth on recruitment. The number of babies born per parent ranged from one to three, and included four multiple births, equating to 116 pregnancies delivered.

Table 1.

Patient recruitment, babies born to AVERT trial staff, and number of participants needed to recruit per baby born (NNRpB)

| No of patients recruited | No of babies | NNRpB (95% CI) | |

| All regions combined | |||

| Total | 2104 | 120* | 17.5 (14.7 to 21.0) |

| By region | |||

| Asia | 251 | 4 | 62.7 (24.8 to 229.4) |

| Australia/New Zealand | 1243 | 83 | 15.0 (12.2 to 18.7) |

| United Kingdom | 610 | 33 | 18.5 (13.3 to 26.6) |

| England | 368 | 16 | — |

| Northern Ireland | 59 | 10 | — |

| Scotland | 171 | 7 | — |

| Wales | 12 | 0 | — |

*11 additional babies born to staff at AVERT Central (the central coordinating trial site) were not included because the staff did not recruit patients.

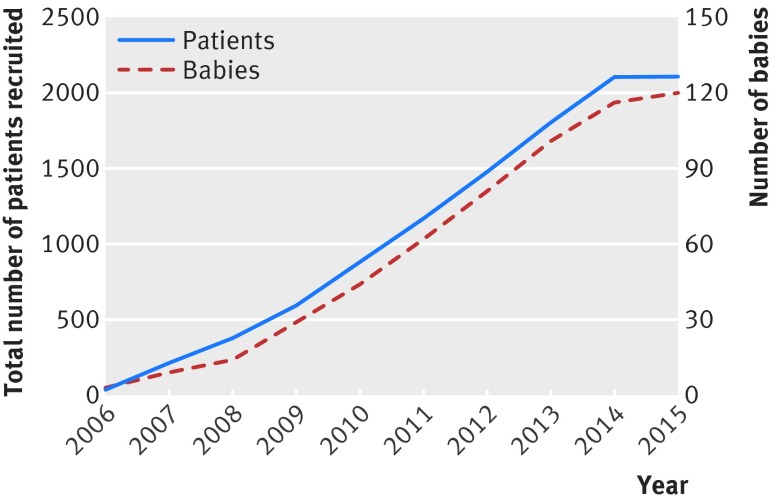

The NNRpB was 17.5 (95% confidence interval 14.7 to 21.0) overall. There was a significant difference in NNRpB by region (P=0.002), with Australia/New Zealand showing the lowest value and Asia the highest. The hazard ratio of patients recruited per baby born was 5.0 in Asia (95% confidence interval 1.6 to 15.4; P=0.005) and 1.8 in the UK (1.2 to 2.9; P=0.009), compared with Australia/New Zealand. Figure 1 shows patient and baby accrual.

Fig 1 Accumulated recruitment of patients and babies born during AVERT

Twenty trial main investigators from 15 sites went on parental leave during the course of the trial. We observed slowing of recruitment during the staff transition phase in most instances. In six instances, birth led to site closure when no alternative local trial champion could be recruited (web appendix 2). However, 46 (47%) parents returned to the trial after parental leave.

Case study

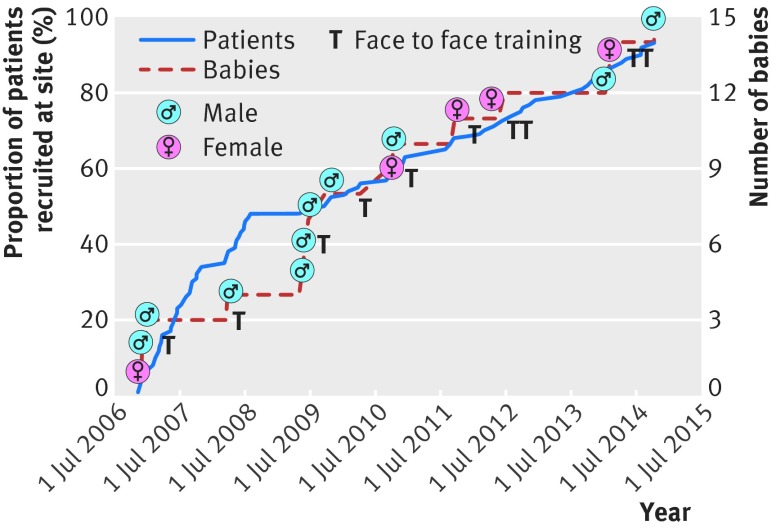

At one foundation site involved for the entire trial, a total of 15 babies were born to trial staff (four born to main investigators) over eight recruitment years (fig 2). Ten additional training sessions were needed for replacement of staff. Three staff had more than one baby, so only 10 sessions were needed. Each training session lasted an average of 2.5 h (total 25 h).

Fig 2 Case study from one selected trial site showing recruitment of patients, babies born to site investigators, and onsite training delivered

Additional administrative management of staff changeover was estimated at about 16 h per session (160 h in total). This extra time was spent on appointments, travel, printing and supply of required documents, administrative tracking, database access setup, report writing and feedback to site, ethics notification, and additional queries by site.

Costs

Births resulted in an estimated 232 months (19 years) of recruitment loss out of our total of 198 recruitment years. Costs arising from births were conservatively estimated at $A0.665m or $A5736 (£2744; €3895; US$4124) per birth episode (web appendix 3).

Staff morale

Each presentation of the baby count graph (web appendix 1) to investigators resulted in loud chuckles.

Discussion

A surprisingly large number of babies were born to AVERT staff during the trial, the unexpected consequences of which included a high number of new recruits, more training, and additional recruitment time and costs. Furthermore, we estimated that site closures or paused recruitment due to parental leave of a critical staff member lost 19 years of recruitment. Parental leave represents a previously unreported source of trial burden on hospital sites and trial coordinating teams. Our estimate of 17.5 NNRpB should assist investigators in planning similar trials in the future.

We believe that AVERT staff were representative of public hospital staff. In Australia, the average age of nurses and physiotherapists is 39.9 years and 36.6 years, respectively, with a ratio of 1 man to 7.6 women.4 5 In Scotland,6 44% of allied health professionals (including physiotherapists) and 33% of nurses are aged less than 40 years, with a ratio of 1 man to 6.7 women. The median age of AVERT staff was somewhat younger. It is unclear whether stroke units attract younger, largely female staff, or whether participation in AVERT was attractive to this group. Older staff with additional responsibilities appeared less inclined to take up a role in the trial. Our results illustrate that planned research involving stroke unit staff should consider the family plans of this group.

The trial challenges we experienced with parental leave reflect the broader challenges in the community. The Australian pregnancy and return to work national review described employers reporting difficulties filling maternity leave positions owing to their often short term nature.7 When external recruitment is necessary, costs and delays increase.7 Clinical care, as well as clinical research, can both be affected in these circumstances.

AVERT, like many ambitious randomised controlled trials, took longer than planned to complete recruitment; our unexpected baby count added costs and delays, requiring grants from many funding agencies around the world (see acknowledgments). Although we wish to alert other researchers to these unexpected costs, we have some additional reflections. Trial success requires careful nurturing of many collaborators, with regular collaborator meetings an essential ingredient of the esprit de corps. Our baby graph became a positive part of the AVERT experience, enjoyed at meetings as a celebration of life.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study included its international reach and large workforce. Results should be generalisable to other rehabilitation studies. However, it is possible that full baby ascertainment was not achieved. We did not systematically conduct exit questionnaires when staff left the study. Impaired memory associated with late pregnancy could have also reduced reporting of baby related information to the trials team,8 which underestimated the workforce fertility rate. Unmeasured factors such as parental leave policy and maternal obesity 9 10 could moderate the association between NNRpB and country. Finally, because only two of our sites were in Asia, the regional differences observed could have been due to chance.

Conclusions

The AVERT trial was associated with a large number of unexpected babies born to trial staff. It is possible that the challenges of trial participation resulted in some team members deciding that having a child would be an easier option at this stage of their lives. It is fair to say, however, that many returned to their senses and resumed their AVERT roles, having realised that research and patient care is perhaps more satisfying than changing endless nappies.

What is already known on this topic

Parental leave represents a previously unreported source of trial burden on hospital sites and trial coordinating teams

What this study adds

Ongoing recruitment and training of new staff is needed to cover parental leave among a young research workforce and the resulting financial costs, which should be considered when planning research and estimating budgets

Celebrating the good stuff, including babies, in large trial collaborations is important, helping to maintain a cohesive collaborative group

The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health acknowledges the strong support from the Victorian government in Australia and in particular the funding from the Operational Infrastructure Support Grant. We thank all parents for volunteering their baby information and for being part of the AVERT Collaboration Group. We thank Brooke Parsons for her longstanding contribution as our consumer representative.

Contributors: RIL, JB, and EL had the idea to publish these data (after an annual collaborators’ meeting). FE, JC, JVH, and JMC collected and organised the data. RIL wrote the first draft, LC provided the statistical analysis, and MM estimated costs associated with births. All authors revised the paper. Members of the AVERT Collaboration Group are listed in web appendix 4.

Funding: Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Singapore Health, Chest Heart and Stroke Scotland, Northern Ireland Chest Heart and Stroke, UK Stroke Association, UK National Institute of Health Research. The funders were not involved in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the views of the funders.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the NHMRC, Singapore Health, Chest Heart and Stroke Scotland, Northern Ireland Chest Heart and Stroke, UK Stroke Association, and UK National Institute of Health Research for the submitted work; AT received funding from the NHMRC (grant no 1042600), during the study; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval: All hospitals participating in the study received ethics approval.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix 1: AVERT baby count graph

Web appendix 2: Summary of recruitment rate pre and post birth

Web appendix 3: Estimated additional costs due to AVERT team births

Web appendix 4: AVERT committees, advisors and coordinating centres

References

- 1.Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Collier Jet al. A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial (AVERT). Int J Stroke 2006;1: 169-71. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2006.00044.x 18706042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernhardt J, Churilov L, Dewey Het al. AVERT Collaborators. Statistical analysis plan (SAP) for A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial (AVERT): an international trial to determine the efficacy and safety of commencing out of bed standing and walking training (very early mobilization) within 24 h of stroke onset vs. usual stroke unit care. Int J Stroke 2015;10: 23-4. 10.1111/ijs.12423 25491547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AVERT Trial Collaboration group. Efficacy and safety of very early mobilisation within 24 h of stroke onset (AVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386: 46-55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60690-0 25892679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Nursing and Midwifery Workforce 2012. Canberra, Australia: 2013 Contract No: HWL 52.

- 5.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Allied Health Workforce 2012. Canberra: 2013 Contract No: HWL 51.

- 6.Information Services Division. Quarterly update of staff in post, vacancies and turnover at 31 March 2015. Information Services Division:2015.

- 7.The Australian Human Rights Commission. Pregnancy and Return to Work National Review. Report. Sydney, Australia: 2014 Contract No: 978-1-921449-54-3.

- 8.Christensen H, Leach LS, Mackinnon A. Cognition in pregnancy and motherhood: prospective cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196: 126-32. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.068635 20118458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castles FG. The world turned upside down: below replacement fertiliy, changing preference and family-friendly public policy in 21 OECD countries. J Eur Soc Policy 2003;13: 209-27 10.1177/09589287030133001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heslehurst N, Rankin J, Wilkinson JR, Summerbell CD. A nationally representative study of maternal obesity in England, UK: trends in incidence and demographic inequalities in 619 323 births, 1989-2007. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34: 420-8. 10.1038/ijo.2009.250 20029373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix 1: AVERT baby count graph

Web appendix 2: Summary of recruitment rate pre and post birth

Web appendix 3: Estimated additional costs due to AVERT team births

Web appendix 4: AVERT committees, advisors and coordinating centres