Abstract

Background:

Little is known about the association of personality traits with intent in attempted suicide.

Aims:

Our objectives were to assess the levels of selected personality factors among suicide attempters and to examine their association with suicide intent.

Materials and Methods:

A chart review of 156 consecutive suicide attempters was carried out. All participants were administered the Beck Suicide Intent Scale, Barratt Impulsivity Scale-11, Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire, and Past Feelings and Acts of Violence Scale to assess suicide intent, trait impulsivity, hostility-aggression, and violence, respectively. Pearson's product moment correlation was the used as the test of association. Stepwise linear regression was used to identify predictors of suicide intent.

Results:

Suicide intent was significantly correlated with verbal aggression (Pearson r = 0.90, P = 0.030), hostility (Pearson r = 0.316, P < 0.001), and nonplanning impulsivity (r = -0.174, P = 0.049). High hostility and low motor impulsivity emerged as significant predictors of suicide intent.

Conclusion:

Personality traits such as hostility and to an extent, impulsivity are accurate predictors of intentionality in attempted suicide. Clinicians should focus on these personality attributes during a routine evaluation of suicide attempters. They can also be considered as potential targets for suicide prevention programs.

Keywords: Aggression, attempted suicide, hostility, impulsivity, personality, suicide intent

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a complex behavior with many socio-psychological determinants. Although a multitude of well-researched risk factors have been identified for suicidal behavior in different patient populations,[1,2,3] empirical research has shown that they are of limited use when dealing with an individual case.[4] In this regard, studying the association between personality traits and key suicide constructs may help in understanding the underlying mechanisms and motivations that culminate in an attempt on one's life and assist clinicians in formulating individual suicide risk.[5] Personality as an underlying factor influencing suicidal behavior is rather unique as it could be a risk or protective factor depending on the traits manifested.[6,7] They could also be measurable endophenotypes in psychiatric illness that are amenable to long-term public health interventions and this enhances their potential clinical value.[8] Furthermore, researchers have shown that selected personality traits may be useful markers of suicide risk in diverse clinical populations.[9,10] In spite of this growing evidence, personality factors contributing to suicide has received comparatively less research attention. As a previous suicide attempt has been shown to be a strong predictor of subsequent attempts and eventual death by suicide,[11] it makes sense to examine this group in some detail. Intent in attempted suicide has shown a robust association with risk of subsequent suicidal behavior and overall mortality.[12,13] This makes it a clinically relevant suicide construct and factors that are correlated with intent also assume significance both from the point of view of assessment as well as management. Impulsivity, hostility-aggressiveness, and violence are major personality attributes shown to be associated with suicidal behavior.[14,15] With this background, we undertook the present study in a group of subjects with attempted suicide presenting to our hospital. The research had two objectives: To measure selected personality traits among the subjects and to assess the relationship of these personality traits with the level of suicide intent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting of the study

The present study was conducted in the Department of Psychiatry of a teaching cum tertiary care hospital located in a semi-urban area of South India. The Department of Psychiatry runs a specialized crisis intervention clinic (CIC) catering to medically stabilized attempted suicide subjects. The CIC uses the definition of “suicide attempt” as stated by Silverman et al.[16] The health-care team at the CIC comprises of a consultant, a resident, and a social worker. Patients who are registered in the clinic are evaluated in detail using a structured proforma that aims to tap both sociodemographic and clinical parameters. Information is gathered by trained residents from the patient, his/her relatives, and available medical records. The management plan for the patient includes psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy either on an inpatient or outpatient basis.

Procedure

The present study included the chart records of consecutive patients registered in the CIC over a period of 1-year (July 2013 to June 2014). Information was extracted from the structured questionnaires of the patients evaluated in the CIC by one of the authors who is a consultant psychiatrist (SK). Data that were extracted included demographic details, the mode and reason of the attempt, information about whether the attempt was conducted under alcohol intoxication. Any past or family history of suicide attempt was also extracted. Data extraction and evaluation of the clinical case records were done as per standard procedures.[17] In addition, structured instruments were used for measurement of suicide intent and trait personality attributes described as follows.

Instruments

Beck Suicide Intent scale

This is a 20 item semi-structured interviewer rated instrument to assess various facets of suicidal intent. The scale encompasses items related to circumstances surrounding the suicide and self-reported seriousness of the suicide attempt. This instrument has been commonly used in the literature to assess the suicidal intent. A higher score suggests higher intent of suicide attempt. Total scores can be used for categorizing suicide attempt into three categories: Low intent (15-19), medium intent (20-28), and high intent (≥29).[18]

Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire

This is a popular 29 item self-rated questionnaire that aims to elicit various domains of aggression. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely uncharacteristic of me” to “extremely characteristic of me.” The scale comprises of 9 items related to physical aggression, 5 items related to verbal aggression, 7 items related to anger, and 8 items related to hostility, thus comprising of four sub-scales.[19] Researchers have shown good test-retest reliability (0.72-0.80) and internal consistency (0.89) for total Buss Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) scores as well as for the 4 sub-scales.[20]

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11

This is a 30 item self-report scale used to measure the personality construct of impulsiveness. It is the most widely referenced instrument for assessment of impulsiveness and has sound psychometric properties. The items are rated on a 4-point Likert type scale from rarely/never to almost always/always. Some of the items are reverse scored. The scale has 3 second order factors representing the multi-dimensional nature of impulsiveness namely : a0 ttentional impulsivity, motor impulsivity, and nonplanning. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-version 11 (BIS) was used for this research.[21]

Past Feelings and Acts of Violence

This is a 12 item self-report instrument designed to assess for the risk of violence. Items focus on feelings of anger and acts of violence against others. The first 3 items deal with aggression, the next six with frequency of violent behaviors, and accessibility to weapons. The next two questions deal with history of aggressive and nonaggressive criminal behavior and the last item asks about presence of weapons at home. All the questions are rated on a 4-point Likert type scale ranging from “never” to “very often” except the last one which is reported as yes/no.[22]

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp, TX, USA). The demographic and clinical characteristics were represented using descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages. The scale and sub-scale scores were computed for various instruments as per scoring instructions. Thereafter, Pearson's product moment correlation analysis was done to find the relationship between Beck Suicide Intent scale (BSIS) and other scales. Stepwise linear regression was conducted to find the independent predictors of suicide intent measured using BSIS. Missing value imputation was not carried out in this study. All statistical tests were carried out for two-tailed significance and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

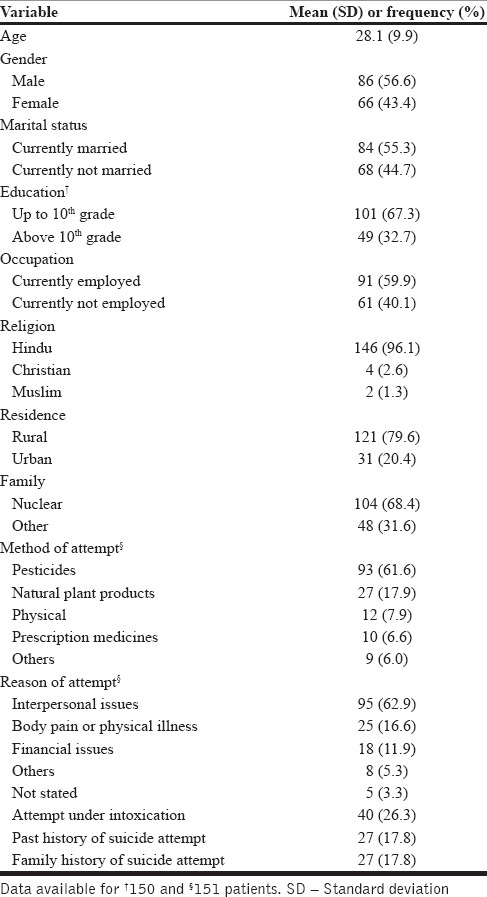

During the course of 1-year, 158 patients were registered in the clinic. Of them, 152 (96.2%) were included in the present analysis as remaining could not be classified as a suicide attempt as per prior definition. The demographic and selected clinical characteristics of this sample (n = 152) is depicted in Table 1. A slight majority of the sample comprised of males, and was currently married. Majority of the sample was educated up to 10th grade, belonged to Hindu religion and a nuclear family. Pesticide ingestion was the most common method of suicide attempt and interpersonal conflicts were the most frequent precipitants. About one-fourth of the sample attempted suicide under alcohol intoxication.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

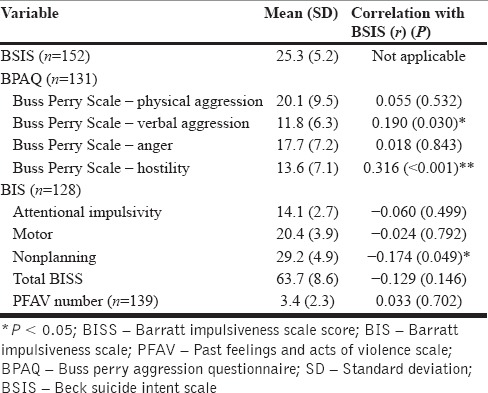

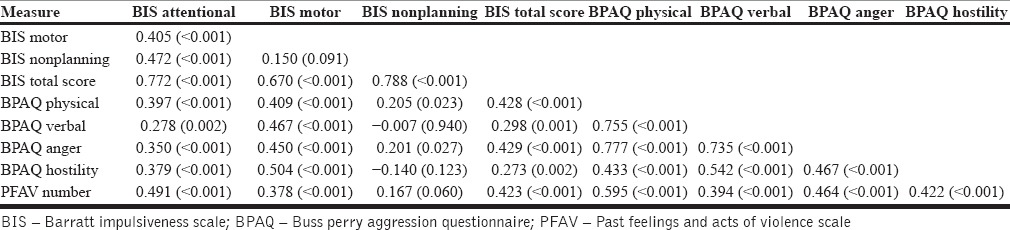

The mean of the BSIS score was 25.3 (±5.2). The findings on the various measures of impulsivity and aggression are depicted in Table 2. The BSIS score had significant positive correlation with verbal aggression and hostility subscales of BPAQ (Pearson r = 0.90, P = 0.030 and r = 0.316, P < 0.001), and negative correlation with nonplanning impulsiveness sub-scale of BIS (r = -0.174, P = 0.049). The correlation matrix between the various scales used to assess personality traits are depicted in Table 3. The BIS sub-scales generally correlated with each other except for the motor and nonplanning domains. The BPAQ sub-scales correlated significantly with each other (all P < 0.001). The Past Feelings and Acts of Violence (PFAV) scores correlated significantly with BIS and BPAQ sub-scale scores except for BIS nonplanning domain.

Table 2.

Measures on suicide intent and other scales

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of various personality scales

The results of stepwise linear regression analysis for predictors of suicide intent are shown in Table 4. The independent variables entered sequentially were age, gender, and the three scale scores. It was observed that higher hostility as per BPAQ and lower motor impulsivity were the independent predictors of greater suicidal intent. The adjusted R2 of the model was 0.160.

Table 4.

Predictors of suicide intent using multiple linear regression analysis

DISCUSSION

In this record based study, we tried to measure the different levels of personality attributes like impulsivity, hostility-aggression, and violence among suicide attempters. Association between severity of suicide intent and these personality attributes was explored. Overall, there was a slight preponderance of male and married subjects in our sample. A few other studies from the region reported a slender female majority in their sample.[23,24] It has been proposed that men make more lethal suicide attempts[25] and hence they may be overrepresented in samples drawn from tertiary health care settings as ours. Usage of pesticides was the most common mode of suicide attempt in our sample and the most common triggers were interpersonal issues. Similar findings have been noted earlier too.[26]

The main focus of the present study was to identify the personality factors that correlated with suicide intent. In this regard, some potentially relevant findings have emerged. Verbal aggression and hostility were positively correlated with intent whereas nonplanning impulsivity correlated inversely with intent. Furthermore, the results of our regression analysis indicate that hostility and lower motor impulsivity are significant predictors of suicide intent. In a case-control study design aimed at assessing risk factors for completed suicide in major depression, Dumais et al. concluded that impulsive-aggressive personality disorders are predictive of eventual suicide.[27] More pertinently, previous authors have noted that impulsivity accurately predicts suicide intent among inpatients with major affective disorders.[28] Empirical research has identified impulsivity as a possible risk factor for suicidal behavior and their relationship has been substantiated in both psychiatric[29] and nonpsychiatric groups.[30] However, its exact relationship with the seriousness of the suicide attempt and how impulsive-aggressive personality traits interact with psychopathology in driving an individual to suicide remains unclear. The problems with existing research have been the use of unclear definitions for impulsivity, not differentiating state and trait aspects of impulsivity, and studying different populations with different measures.[14] We have assessed trait impulsivity in our population of suicide attempters. Hence, our findings basically expand the scope and relevance of impulsivity as a probable predictor of suicide intent in Indian subjects with attempted suicide. The relationship between impulsivity and suicide intent merits a closer evaluation for its preventive implications. Whether and to what extent targeting these personality traits in suicide prevention programs may reduce repeat attempts in follow-up is a question that needs further research. A recent review has provided promising evidence of specific interventions aimed at reducing risk-taking behaviors among impulsive adolescents with drug abuse.[31] This can be adapted for use in high-risk suicidal populations.

Comparatively fewer studies have directly examined the relationship between hostility and suicide intent. We observed that hostility scores are predictive of suicide intent in our sample. Szabo, in an unpublished dissertation, studied the relationship between hostility and suicide intent and concluded that inwardly directed hostility significantly predicted suicide intent scores even after controlling for sociodemographic factors and underlying psychiatric diagnosis.[32] Cognitive hostility was found to predict suicide risk in a large scale prospectively designed study after controlling for potential confounders including depression.[15] Both these results further substantiate our findings. Higher hostility levels have been generally noted in suicide attempters as a group.[33] None other than Freud, himself has stressed the role of introjected hostility in suicide.[34] However, the complex nature of the construct together with its overlap with related personality factors such as aggression and impulsiveness has hindered the understanding of its exact role and direction in suicide, especially when there is underlying psychiatric morbidity. This must be clarified through future research using well-defined populations and standard measures.

Significant associations were observed between impulsivity, hostility-aggressiveness, and violence sub-scale scores and also with each other. Based on our findings, we would like to put forth a putative life course model for the role of personality in suicide. Adverse early life experiences such as physical and emotional abuse or neglect among others has been shown to influence development of various forms of impulsivity such as risk taking behaviors and predispose an individual to react without much forethought to stressful situations.[31] Consistent externally directed angry, impulsive responses to situations, also called reactive aggression,[35,36] may predispose individuals to encounter interpersonal difficulties and other stressful life events on a more regular basis. When such high levels of hostility and aggression co-exist with impulsivity, it may drive an individual to rapidly transition from suicidal thoughts to suicidal behavior as a possible response to the stressful situation precluding other adaptive responses.

One of the major drawbacks in comparing cross-cultural suicide literature is the use of varied definitions and populations for suicide often resulting in a mixed sample that also comprises of various forms of parasuicide apart from attempted suicide. The strengths of our work include studying a sample of suicide attempters defined as per internationally accepted nomenclature, measuring trait levels of selected personality factors and estimating their association with suicide intent about which there is limited information from Indian setting. However, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the fact that our sample was entirely drawn from a single center which was a tertiary care hospital setting. Our research also has all the limitations of being a record based study including, possible under-reporting of data by patients and clinicians. Further, we could not classify the suicide attempts retrospectively for their potential lethality or correlate the same with study variables.

To conclude, this record based study of suicide attempters shows that there is a significant association between intent in attempted suicide and certain personality factors such as verbal aggression, hostility, and impulsivity. High hostility and lower motor impulsivity predicted suicide intent and are therefore of potential clinical value. Clinicians would be well advised to evaluate the presence and severity of these personality factors during a routine evaluation of suicide attempters. Future researchers must study the impact of interventions targeted at modifying these personality attributes on long-term outcomes in suicidal behavior across different ethnic and cultural settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A preliminary version of this paper was presented orally at the 5th Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Psychosocial Rehabilitation held at Bengaluru, India from 6th to 8th February 2015.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hawton K, Casañas I Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harriss L. Suicide and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: A systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:693–704. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Large M, Smith G, Sharma S, Nielssen O, Singh SP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical factors associated with the suicide of psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:18–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pokorny AD. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Report of a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:249–57. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790030019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menon V. Suicide risk assessment and formulation: An update. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:430–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chioqueta AP, Stiles TC. Personality traits and the development of depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation. Pers ndivid Differ. 2005;38:1283–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velting DM. Suicidal ideation and the five-factor model of personality. Pers Individ Differ. 1999;27:943–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savitz JB, Cupido CL, Ramesar RS. Trends in suicidology: Personality as an endophenotype for molecular genetic nvestigations. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Personality traits and cognitive styles as risk factors for serious suicide attempts among young people. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29:37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maser JD, Akiskal HS, Schettler P, Scheftner W, Mueller T, Endicott J, et al. Can temperament identify affectively ill patients who engage in lethal or near-lethal suicidal behavior. A 14-year prospective study? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:10–32. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.10.22183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diekstra RF. The epidemiology of suicide and parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1993;371:9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb05368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harriss L, Hawton K, Zahl D. Value of measuring suicidal intent in the assessment of people attending hospital following self-poisoning or self-injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:60–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suominen K, Isometsä E, Ostamo A, Lönnqvist J. Level of suicidal intent predicts overall mortality and suicide after attempted suicide: A 12-year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gvion Y, Apter A. Aggression, impulsivity, and suicide behavior: A review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res. 2011;15:93–112. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2011.565265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemogne C, Fossati P, Limosin F, Nabi H, Encrenaz G, Bonenfant S, et al. Cognitive hostility and suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:62–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O’Carroll PW, Joiner TE., Jr Rebuilding the tower of babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: Suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:264–77. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarkar S, Seshadri D. Conducting record review studies in clinical practice. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:JG01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8301.4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck A, Schuyler D, Herman I. Development of suicidal intent scales. In: Beck AT, Resnick HL, Lettier AJ, editors. The Prediction of Suicide. Bowie, MD: Charles Press Publishers; 1974. pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant FB, Smith BD. Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss-Perry aggression questionnaire. J Res Pers. 2001;35:138–67. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plutchik R, van Praag HM. A self-report measure of violence risk, II. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31:450–6. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(90)90031-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar PN, George B. Life events, social support, coping strategies, and quality of life in attempted suicide: A case-control study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:46–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar PN, Rajmohan V, Sushil K. An exploratory analysis of personality factors contributed to suicide attempts. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:378–84. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.122231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dombrovski AY, Szanto K, Duberstein P, Conner KR, Houck PR, Conwell Y. Sex differences in correlates of suicide attempt lethality in late life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:905–13. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181860034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menon V, Kattimani S, Shrivastava MK, Thazath HK. Clinical and socio-demographic correlates of suicidal intent among young adults: A study from South India. Crisis. 2013;34:282–8. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dumais A, Lesage AD, Alda M, Rouleau G, Dumont M, Chawky N, et al. Risk factors for suicide completion in major depression: A case-control study of impulsive and aggressive behaviors in men. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2116–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pompili M, Innamorati M, Raja M, Falcone I, Ducci G, Angeletti G, et al. Suicide risk in depression and bipolar disorder: Do impulsiveness-aggressiveness and pharmacotherapy predict suicidal intent? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:247–55. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giegling I, Olgiati P, Hartmann AM, Calati R, Möller HJ, Rujescu D, et al. Personality and attempted suicide. Analysis of anger, aggression and impulsivity. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:1262–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Marsh DM, Papageorgiou TD, Swann AC, Moeller FG. Laboratory measured behavioral mpulsivity relates to suicide attempt history. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34:374–85. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.4.374.53738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romer D. Adolescent risk taking, impulsivity, and brain development:Implications for prevention. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52:263–76. doi: 10.1002/dev.20442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szabo PF. Electronic Thesis and Dissertations, Paper 4244. 1992. The Role of Hostility against Self in Suicide Attempt. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weissman M, Fox K, Klerman GL. Hostility and depression associated with suicide attempts. Am J Psychiatry. 1973;130:450–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.130.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freud S. Mourning and Melancholia. Standard Edition. Vol. 14. London: The Hogarth Press; 1917. pp. 243–58. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coccaro EF, Bergeman CS, Kavoussi RJ, Seroczynski AD. Heritability of aggression and irritability: A twin study of the Buss-Durkee aggression scales in adult male subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:273–84. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seroczynski AD, Bergeman CS, Coccaro EF. Etiology of the impulsivity/aggression relationship: genes or environment? Psychiatry Res. 1999;86:41–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]