Abstract

Background:

Improving functioning levels are an important goal of treatment in schizophrenia. Most studies have described long-term course and outcome in schizophrenia. However, understanding factors influencing functioning in the immediate recovery period following an acute exacerbation may be of important clinical relevance.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to assess the factors that influence well-being and socio-occupational functioning following an acute exacerbation in schizophrenia patients.

Materials and Methods:

The study included 40 patients during the period from June 2013 to June 2014. The possible effect of gender, duration of illness, duration of untreated psychosis, premorbid adjustment, cognitive impairment, facial affect perception and treatment compliance on well-being, and socio-occupational functioning was examined.

Results:

About 45% of the individuals experienced below average well-being. On logistic regression analysis poor compliance with medication and poorer cognitive functioning significantly differentiated the patient group with below average well-being from those with an above average well-being. Male gender, poor premorbid adjustment, poor compliance to treatment, poor cognitive functioning, and greater duration of untreated psychosis were found to be associated with a poorer socio-occupational functioning.

Conclusion:

Clinical interventions focusing on improving cognitive impairment and compliance to treatment could play a role in improving well-being, and socio-occupational functioning in schizophrenia patients following an acute exacerbation.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, socio-occupational functioning, well-being

INTRODUCTION

Functional remission is increasingly being realized as one of the important goals of management in the treatment of schizophrenia. The period following an acute episode is an important phase in the course of the illness, which can determine the outcome. Improved personal and social functioning are one of the important determinants of favorable outcome.[1] One of the variables looking into a social outcome is a general subjective sense of well-being.[2] General subjective well-being is a broad construct that reflects people's emotional and cognitive evaluations of their lives.[3] Subjective well-being is also an important factor in the choice of medication and medication adherence.[4]

Social functioning has been defined globally as the capacity of a person to function in different societal roles such as homemaker, worker, student, spouse, family member, or friend. The definition also takes account of an individuals’ satisfaction with their ability to meet these roles, to take care of themselves, and the extent of their leisure and recreational activities.[5] Occupational status at admission has been shown to be predictive of functional outcome, as unemployed patients show significantly worse functional outcomes.[6] Patients with longer overall illness duration appear to have less favorable functional outcomes as do patients with illnesses characterized by episodes of long duration.[6]

Brekke et al.[7] reported in his study that the influence of neurocognition on the social and functional variables was entirely mediated through the perception of emotion. In stabilized community patients with schizophrenia, affect recognition deficits have significant consequences for social functioning, independently of basic neurocognition.[8] Premorbid functioning has also been extensively studied and is found to be an important predictor of the course and outcome of the illness.[9]

In the SOHO study,[10] subjective well-being was taken as a baseline outcome measure along with other variables such age, gender, duration of illness. Among the other clinical variables age, the onset of illness, insight measures, symptom severity, general psychopathology, and antipsychotic-induced side effects were all significantly related to the quality of life (QOL) scores.[11]

Similarly, compliance to medications have been studied with the QOL and has been found to be a predictor of functional outcome.[12,13]

The focus of management in schizophrenia is slowly taking a turn from medical management to functional recovery. Understanding these factors, which can influence socio-occupational functioning and well-being can have important clinical relevance in improving outcomes in schizophrenia. Therefore, the recent upsurge in interest regarding social outcomes in schizophrenia is exciting and timely.

The present study was conducted with an aim to evaluate the factors influencing socio-occupational functioning and well-being in schizophrenia patients following an acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The study was conducted in the Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka, India over a period of 1 year from June 2013 to June 2014 after receiving the approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. A total of 107 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, who were inpatients in our hospital for an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms in the last 1 year, formed the universe of the study. 40 of these patients who gave informed consent and fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criterion were recruited for the study within 6 months after discharge. Inclusion criterion at the time of assessment included:

Age between 18 and 55 years.

Diagnosis of schizophrenia (International Classification of Diseases-10).[14]

History of exacerbation of psychotic symptoms in last 6 months requiring in-patient care.

Written informed consent.

A patient who were “clinically stable” at the time of conducting the study.

The term “clinically stable” was defined as:

Patients on a stable dose of antipsychotics for at least 6 weeks prior to assessment.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)[15] score of <60 at the time of baseline assessment.

Clinical global impression severity score[16] ≤2.

The exclusion criterion included:

Patients diagnosed with the first episode of psychosis <3 months duration.

Patients with a comorbid neurological disorder such as seizure disorder or mental retardation.

The presence of post schizophrenia depression.

Tools and assessment

The primary outcome measure included socio-occupational functioning as assessed on the socio-occupational functioning scale (SOFS).[17] The scale has 14 items rated on a 5-point spectrum (1 = no impairment, 5 = extreme impairment). A total score was calculated. Higher score revealed the greater difficulty in socio-occupational functioning. Subjective well-being was assessed on the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS).[18] It covers most aspects of positive mental health (positive thoughts and feelings) currently in the literature, including both hedonic and eudemonic perspectives. A score of 51 or higher showed above average and a score <51 showed below average well-being levels. Based on the literature review the factors commonly known to influence outcome in schizophrenia were selected. These included gender, age at onset of psychosis, duration of illness, duration of untreated psychosis, premorbid adjustment as assessed on the Abbreviated Scale of Premorbid Personal-Social Adjustment,[19] cognitive abilities as assessed on the cognitive assessment interview (CAI),[20] facial affect recognition as assessed on tool for recognition of emotions in neuropsychiatric disorders (Behere et al. 2008),[21] compliance to medication as assessed on drug attitude inventory.[22] Information on age at onset, duration of illness, duration of untreated psychosis was obtained from the caregiver of the patient and corroborated with information as recorded in the medical records.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) 16.0 was used for the statistical analysis. Patients were divided into two groups — Above average and below average well-being based on their score on the WEMWBS (a score greater or less than 51, respectively). The main effect of a group of continuous variables was assessed on multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). Previous studies have shown that the number of previous exacerbations can have a bearing on well-being and functioning.[23] Hence, to control for this confounding factor, statistical analysis was performed using the number of previous episodes as a covariate. Effect of categorical variables was assessed on Chi-square test. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed between SOFS scores and the study variables. The significant variables were entered into a logistic regression model to assess the factors differentiating patient groups with above average and below average well-being.

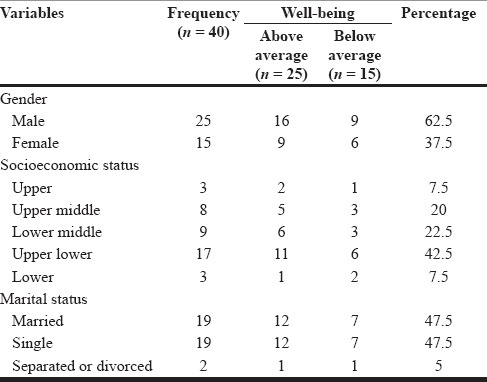

RESULTS [TABLE 1]

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of patient groups

Results of well-being analysis

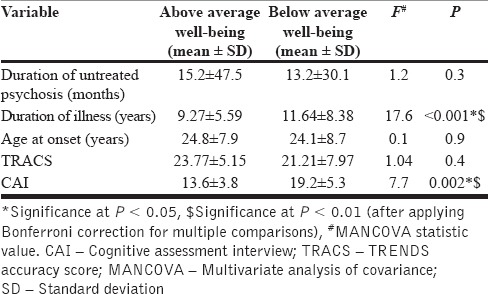

A total of 22 (55%) subjects had above average well-being as compared to 18 (45%) individuals who experienced below average well-being. On MANCOVA there was a significant main effect of group on duration of illness (F = 17.6, P < 0.001) and CAI (F = 7.7, P = 0.002) [Tables 2 and 3]. The effect was significant even after applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (significance at P < 0.01).

Table 2.

MANCOVA of variables affecting well-being

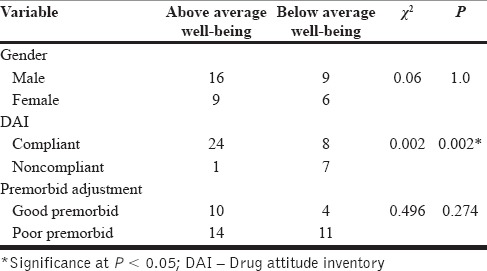

Table 3.

Chi-square analysis of variables on well-being

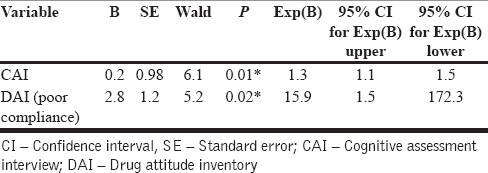

The variables that emerged significant in the above analysis - duration of illness, CAI and DAI were entered into a Binomial logistic regression analysis model. On analysis, CAI and DAI significantly differentiated between patient groups with above average and below average well-being. The model explained 52.3% of the variance in well-being and correctly classified 61.5% of patients with below average well-being. Patients with poor treatment compliance were 15.9 times more likely to experience below average well-being. Greater scores on CAI was associated with a below average well-being [Table 4].

Table 4.

Results of binomial logistic regression model of factors influencing well-being

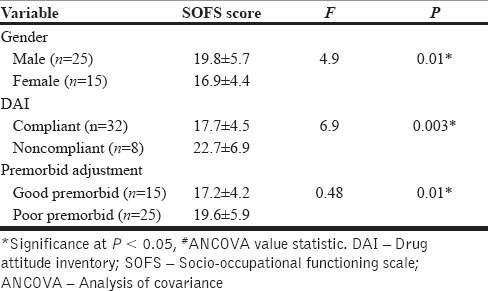

Results of socio-occupational functioning analysis

Using analysis of covariance, we studied the effect of gender, drug compliance and premorbid adjustment on SOFS scores with the number of previous exacerbations as the covariate. Male gender, a group with poor treatment compliance and a group with poor premorbid adjustment had significantly poorer socio-occupational functioning. On correlation analysis, there was also a positive correlation between scores on CAI and SOFS score (r = 0.415) (P = 0.009), suggesting that poor cognitive function was associated with poorer socio-occupational functioning. Greater duration of untreated psychosis was also associated with poorer socio-occupational functioning (r = 0.340) (0.032) No significant correlation was found for SOFS with duration of illness (r = 0.146) (P = 0.369), TRENDS accuracy scores(r = −0.203) (P = 0.227). The values of other variables are as mentioned in the Table 5.

Table 5.

Effect of gender, DAI and premorbid adjustment on SOFS scores on ANCOVA

DISCUSSION

We examined the factors that are likely to influence the socio-occupational functioning and well-being in schizophrenia patients following an acute exacerbation. Number of previous episodes of exacerbation which could confound the results was controlled for. The main results of the study are:

45% patients of patients experienced below average well-being.

Factors associated with a below average well-being included a longer duration of illness, poor compliance with medication and poorer cognitive functioning.

On logistic regression analysis only poor compliance with medication and poorer cognitive functioning significantly differentiated patient groups with below average well-being from the group with above average well-being.

Male gender, poor premorbid adjustment, poor compliance to treatment, poor cognitive functioning and greater duration of untreated psychosis was found to be associated with a poorer socio-occupational functioning.

Well-being and schizophrenia

Both illness and treatment has been found to cause a low sense of well-being in patients affected with the chronic psychotic illness. Concept formation and judgment was found to be better in patients who were compliant on medications.[13] Similarly in our study, we found greater cognitive deficits and poor compliance to medication to be associated with a lower sense of well-being. Another study on social cognition, and its relation to QOL in schizophrenia found impairment in the theory of mind rather than emotion perception to have an impact on QOL.[24] In our study, though patients with below average well-being had lower TRENDS accuracy score, the difference was not significant. Hence, facial emotion perception may not be a factor important in influencing well-being.

Among the clinical variables, we did not find any association between duration of untreated psychosis and well-being which was consistent with findings reported in earlier studies.[25] The longer the time spent in illness, the greater the adverse experiences, thus leading to a negative attitude toward the illness. We found in our study that the duration of the illness have a significant association with subjective well-being. In our study, we did not find any association between premorbid functioning and well-being. Most of the studies report of poor premorbid adjustment associated with poor QOL.[26] The majority of those were retrospective studies, and none directly looked into the premorbid functioning and well-being in an individual.

Socio-occupational functioning and schizophrenia

In our study, a longer duration of untreated psychosis had a significant association with lower socio-occupational functioning. This finding was similar to a study by Thirthalli et al. in a treatment naïve population.[27] In addition, we also found male gender and poor premorbid adjustment to be associated with poor functioning. This finding was consistent with other studies.[28,29]

In our study, there was a significant correlation between cognitive deficit and higher deficit scores on SOFS. This was consistent with findings reported by Lee et al.[30] where they found neuropsychological functioning as the best independent predictor of functional outcome. This may reflect underlying changes in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which can predict the poorer long-term outcome.[31] The other significant variable that showed a correlation with socio-occupational functioning was the drug attitude of the individual. People who were compliant to medication were found to have a better socio-occupational functioning. Tsai et al. in 2011[32] also found a similar association between drug attitude and personal and social performance.

Clinical implications

The factors found significant in our study can possibly be divided as modifiable and fixed factors. The fixed factors would include gender and premorbid adjustment while the modifiable factors would include duration of illness and untreated psychosis, cognitive impairment, and compliance to treatment. A multi-modal approach toward raising community awareness, early recognition of signs of psychotic disorders and interventions such as cognitive remediation, compliance and insight facilitation oriented therapies could play an important role in improving outcomes, and well-being in patients following an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.

The unique aspect of this study is the selection of the sample. Patients in the sample were assessed within 6 weeks to 6 months of an acute exacerbation and had a PANSS score of <60 indicating that they did not have very prominent negative or positive symptom. This sample of patients closely mimics the real world patients who might be expected to have relatively better levels of functioning and benefit from rehabilitation strategies. Rosen and Garety[23] demonstrated that subsequent experiences during episodes had an effect on outcome in patients with schizophrenia as compared to those who had only a single episode. To control for this effect number of previous episodes of exacerbation was used as a covariate in the statistical analysis. In this study, we did not specifically assess for treatment-related side effects, which can directly influence compliance and have bearing on well-being. Further, our sample may be not be wholly representative as out of 107 patients admitted in our center for an acute exacerbation we could assess only 40 patients.

CONCLUSION

We attempted to examine factors influencing well-being and socio-occupational functioning in a group of patients following an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. We found that male gender, poor premorbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis was associated with a poorer socio-occupational functioning while greater cognitive impairment, and poor compliance with medication were associated with both poor socio-occupational functioning, and a below average well-being. Interventions aimed at cognitive remediation and compliance to treatment could possibly improve the well-being and functioning in patients after an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Stewart Brown and Dr. Joseph Ventura for giving us permission to use WEMWMS and CAI scale respectively in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tulloch AD, Fearon P, David AS. Social outcomes in schizophrenia: From description to action. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:140–4. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000214338.29378.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wehmeier PM, Kluge M, Schacht A, Helsberg K, Schreiber W, Schimmelmann BG, et al. Patterns of physician and patient rated quality of life during antipsychotic treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:676–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diener E, Oishi S, Lucas RE. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:403–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Millas W, Lambert M, Naber D. The impact of subjective well-being under neuroleptic treatment on compliance and remission. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:131–6. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.1/wmillas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brissos S, Molodynski A, Dias VV, Figueira ML. The importance of measuring psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2011;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schennach-Wolff R, Jäger M, Seemüller F, Obermeier M, Messer T, Laux G, et al. Defining and predicting functional outcome in schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2009;113:210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brekke J, Kay DD, Lee KS, Green MF. Biosocial pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:213–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan YJ, Chen SH, Chen WJ, Liu SK. Affect recognition as an independent social function determinant in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:443–52. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips L. Case history data and prognosis in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1953;117:515–25. doi: 10.1097/00005053-195306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haro JM, Edgell ET, Frewer P, Alonso J, Jones PB. SOHO Study Group. The European Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes Study: Baseline findings across country and treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;416:7–15. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.107.s416.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kao YC, Liu YP, Chou MK, Cheng TH. Subjective quality of life in patients with chronic schizophrenia: Relationships between psychosocial and clinical characteristics. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortesi PA, Mencacci C, Luigi F, Pirfo E, Berto P, Sturkenboom MC, et al. Compliance, persistence, costs and quality of life in young patients treated with antipsychotic drugs: Results from the COMETA study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awad AG, Hogan TP, Voruganti LN, Heslegrave RJ. Patients’ subjective experiences on antipsychotic medications: Implications for outcome and quality of life. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(Suppl 3):123–32. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992b. The ICD-l0 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saraswat N, Rao K, Subbakrishna DK, Gangadhar BN. The Social Occupational Functioning Scale (SOFS): A brief measure of functional status in persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;81:301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of life Outcomes; 2007;5:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris JG., Jr An abbreviated form of the Phillips rating scale of premorbid adjustment in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84:129–37. doi: 10.1037/h0076983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ventura J, Cienfuegos A, Boxer O, Bilder R. Clinical global impression of cognition in schizophrenia (CGI-CogS): Reliability and validity of a co-primary measure of cognition. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behere RV, Raghunandan VN, Venkatasubramanian G, Subbakrishna DK, Jayakumar PN, Gangadhar BN. TRENDS: A tool for recogniton of emotions in neuropsychiatric disorders. Indian J Psychol Med. 2008;30:32–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: Reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–83. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen K, Garety P. Predicting recovery from schizophrenia: A retrospective comparison of characteristics at onset of people with single and multiple episodes. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:735–50. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maat A, Fett AK, Derks E Group Investigators. Social cognition and quality of life in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho BC, Nopoulos P, Flaum M, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Two-year outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: Predictive value of symptoms for quality of life. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1196–201. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malla A, Payne J. First-episode psychosis: Psychopathology, quality of life, and functional outcome. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:650–71. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thirthalli J, Channaveerachari NK, Subbakrishna DK, Cottler LB, Varghese M, Gangadhar BN. Prospective study of duration of untreated psychosis and outcome of never-treated patients with schizophrenia in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:319–23. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.91905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Addington J, Addington D. Premorbid functioning, cognitive functioning, symptoms and outcome in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert M, Karow A, Leucht S, Schimmelmann BG, Naber D. Remission in schizophrenia: Validity, frequency, predictors, and patients’ perspective 5 years later. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:393–407. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.3/mlambert. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee RS, Hermens DF, Redoblado-Hodge MA, Naismith SL, Porter MA, Kaur M, et al. Neuropsychological and socio-occupational functioning in young psychiatric outpatients: A longitudinal investigation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behere RV. Dorsolateral prefrontal lobe volume and neurological soft signs as predictors of clinical social and functional outcome in schizophrenia: A longitudinal study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:111–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.111445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai JK, Lin WK, Lung FW. Social interaction and drug attitude effectiveness in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 2011;82:343–51. doi: 10.1007/s11126-011-9177-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]