Abstract

Introduction

Postoperative anastomotic leak and stricture are dramatic events that cause increased morbidity and mortality, for this reason it's important to evaluate which is the best way to perform the anastomosis.

Aim

To compare the techniques of manual (hand-sewn) and mechanic (stapler) esophagogastric anastomosis after resection of malignant neoplasm of esophagus, as the occurrence of anastomotic leak, anastomotic stricture, blood loss, cardiac and pulmonary complications, mortality and surgical time.

Methods

A systematic review of randomized clinical trials, which included studies from four databases (Medline, Embase, Cochrane and Lilacs) using the combination of descriptors (anastomosis, surgical) and (esophagectomy) was performed.

Results

Thirteen randomized trials were included, totaling 1778 patients, 889 in the hand-sewn group and 889 in the stapler group. The stapler reduced bleeding (p <0.03) and operating time (p<0.00001) when compared to hand-sewn after esophageal resection. However, stapler increased the risk of anastomotic stricture (NNH=33), pulmonary complications (NNH=12) and mortality (NNH=33). There was no significant difference in relation to anastomotic leak (p=0.76) and cardiac complications (p=0.96).

Conclusion

After resection of esophageal cancer, the use of stapler shown to reduce blood loss and surgical time, but increased the incidence of anastomotic stricture, pulmonary complications and mortality.

Keywords: Esophagectomy, Surgical anastomosis, Meta-analysis

Abstract

Introdução:

Deiscências e estenoses anastomóticas pós-operatórias são eventos dramáticos que causam aumento da morbimortalidade; por esta razão é sempre importante avaliar qual é o melhor meio de se fazer as anastomoses.

Objetivo:

Comparar as técnicas de anastomose esofagogástrica manual e mecânica, após ressecção de neoplasia maligna de esôfago, quanto à ocorrência de fístula, estenose, sangramento, complicações cardíacas e pulmonares, mortalidade e tempo cirúrgico.

Métodos:

Foi realizada uma revisão sistemática de ensaios clínicos randomizados, que incluiu estudos de quatro bases de dados (Medline, Embase, Cochrane e Lilacs) usando a combinação dos descritores (anastomosis, surgical) and (esophagectomy).

Resultados:

Treze ensaios clínicos randomizados foram incluídos, totalizando 1778 pacientes, sendo 889 no grupo da anastomose manual e 889 no grupo da anastomose mecânica. A anastomose mecânica reduziu o sangramento (p<0,03) e o tempo cirúrgico (p<0,00001) quando comparado à anastomose manual pós ressecção esofágica. No entanto, a anastomose mecânica aumentou o risco de estenose (NNH=33), complicações pulmonares (NNH=12) e mortalidade (NNH=33). Não houve diferença significativa em relação à formação de fístulas (p=0,76) e complicações cardíacas (p=0,96).

Conclusão:

Após ressecção de neoplasia esofágica, o uso da anastomose mecânica demonstrou reduzir o sangramento e o tempo cirúrgico, porém aumentou a incidência de estenose, complicações pulmonares e mortalidade.

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Cancer Institute, in the period of 2006 to 2010, the incidence of esophageal cancer was 4,4/100.000 habitants per year, and at the same period the mortality rate was 4,3/100.000 habitants per year.10 According to INCA, at the year of 2012, the new cases of esophageal cancer were estimated at 10.420, being 7.700 in men and 2.650 in women.6 Therefore, it is a severe disease with poor prognosis.

The surgical resection is one option of treatment of esophageal cancer. The esophagogastric anastomosis is a basic component and aims to restore the continuity feed15, and can performed using manual (hand-sewn) or mechanical (stapled) suture.

The advent of stapled, released from the decade of 60, by Ravitch & Steichen21, caused the development of an apparatus characterized by increased security, accuracy and speed at this form trying to reduce the risk of anastomotic leak, beyond simplify the realization.11,19,24 The stapled decreases the occurrence of trauma, allows the uniformity of the anastomosis and a shorter surgical time; however, increases costs and the incidence of anastomotic stricture. The hand-sewn depends more of the surgeon ability and certainly is cheaper than stapled.15

Postoperative anastomotic leak and stricture are dramatic events that cause increased morbidity and mortality, for this reason it's important to evaluate which is the best way to perform the anastomosis. The anastomotic leak decreases the patient quality of life, retard early feedings, requires laborious local care and prolongs hospitalization. In addition, patients who develop anastomotic leak 30 to 50% progress to anastomotic stricture. Anastomotic stricture occurs in 5 to 46% of operated cases and can manifest up to a year after surgery.8

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to compare hand-sewn and stapled after resection of malignant neoplasm of esophagus.

METHODS

Identification and selection of studies

A search of electronic literature was done through the data bases Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and Lilacs. On Medline the combination of terms (anastomosis, surgical) and (esophagectomy) were utilized in the interface Clinical Queries (Therapy/Narrow[filter]). On Embase, was utilized the following search strategy: (anastomosis, surgical) and (esophagectomy) and (randomized controlled trial). On Lilacs and Cochrane, the keywords used were: (surgical anastomosis) and (esophagectomy). Manual searches were done among study references found. The searches ended on July 2, 2013.

The articles were selected independently and in pairs, by reading the titles and abstracts. Any difference between the articles was resolved by consensus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: Randomized controlled trials were included irrespective of publication status, countries or languages; patients of any age and gender who underwent esophagectomy and reconstruction for esophageal cancer of any histological type; comparison of mechanic anastomosis and manual esophagogastric anastomosis. There were no restrictions on the path of reconstruction and the anastomotic site.

Exclusion criteria: Non-randomized trials, cohort, case-control and case report; patients undergoing emergency procedure and dealing only with benign esophageal diseases.

Outcomes analyzed

Primary outcomes: anastomotic leak and stricture.

Secondary outcomes: surgical time, bleeding, mortality, cardiac complications and pulmonary complications.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the primary studies was evaluated by the GRADE system proposed by the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation group3.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed with the Review Manager 5.2 program. Data were evaluated by intention-to-treat, meaning the patients that did not undergo the proposed intervention or patients lost in follow-up during the study were considered as clinical outcomes.

The evaluation of the dichotomic variables was performed by the difference in absolute risk (RD) adopting a 95% confidence interval. When there was a statistically significant difference between the groups, the number needed to treat (NNT) or the number needed to cause harm (NNH) was calculated. The continuous variables were evaluated by the difference in means (MD). Studies that did not show data in terms of means and their respective standard deviations were not included in the analyses.

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

Inconsistencies among the clinical studies were estimated using the chi-squared heterogeneity test and quantified using I2. A value above 50% was considered substantial. Studies that generated heterogeneity were represented by funnel plots.

RESULTS

Study Selection

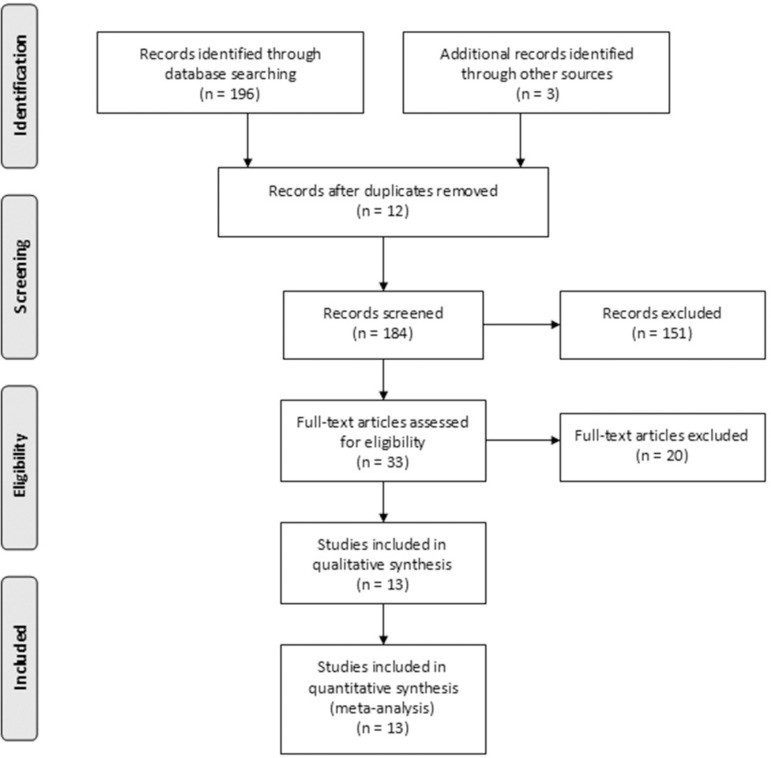

Through eletronic search 196 articles were recovered (Medline=42; Embase=89; Cochrane=34 e Lilacs=28). At manual search, three other articles were found beyond the previously selected. Initially 151 articles were excluded by not treating of randomized controlled trials. Thirty tree articles have been pre selected, but 20 did not meet the inclusion criteria. So at this revision, 13 randomized controlled trials were included (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Search algorithm of the articles. PRISMA adapted. n= number of articles

The 13 studies included randomized the patients in two groups, hand-sewn (group 1) and stapled (group 2), totaling 1778 patients, 889 from group 1 and 889 from group 2.

Included studies, year of publication, number of patients in each group and histological type are shown on Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Description of the included studies

| Histological type of neoplasm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wshasg27 | 1991 | 25 | 27 | NA |

| Valverde25 | 1996 | 74 | 78 | NA |

| Craig5 | 1996 | 50 | 50 | SCC e AC |

| Law15 | 1997 | 61 | 61 | SCC |

| Laterza14 | 1999 | 21 | 28 | SCC e AC |

| Walther26 | 2003 | 41 | 42 | SCC e AC |

| Hsu11 | 2004 | 32 | 31 | SCC |

| Okuyama19 | 2007 | 18 | 14 | SCC |

| Luechakiettisak17 | 2008 | 59 | 58 | SCC |

| Zhang29 | 2010 | 244 | 272 | NA |

| Ma18 | 2010 | 52 | 47 | SCC e AC |

| Cayi4 | 2012 | 125 | 102 | SCC e AC |

| Saluja22 | 2012 | 87 | 87 | SCC e AC |

Legend: SCC=squamous cell carcinoma; AC=adenocarcinoma; NA=not available

Evaluation of methodological quality performed by GRADE is represented on Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Methodological evaluation by GRADE

| Parameters Evaluated | Wshasg 1991 | Valverde 1996 | Craig 1996 | Law 1997 | Laterza 1999 | Walther 2003 | Hsu 2004 | Okuyama 2007 | Luechakiettisak 2008 | Zhang 2010 | Ma 2010 | Cayi 2012 | Saluja 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Was the study randomized? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the allocation of patients to groups confidential? | NA | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | NA | Y | NA | Y |

| Were patients analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized (was the analysis by intention to treat)? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were patients in both groups similar with respect to the previously known prognostic factors? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the study blind? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Except the experimental intervention, were the groups treated equally? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the losses significant? | NA | NA | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Did the study have a precision estimate for the effects of treatment? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Are the study patients similar to those of interest? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Are the outcomes of the study clinically relevant? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were the potential conflicts of interest declared? | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

Legend: Y=yes, N=no, NA=not available

Anastomotic stricture

Eleven primary studies analyzed the anastomotic stricture outcome. The incidence of anastomotic stricture was 12,33% in stapled group (99 of 803 patients) and 9,26% in hand-sewn group (75 of 810 patients). The mechanical anastomosis increased the absolute risk of anastomotic stricture in 3% (CI 95% 0,00 a 0,06; p<0,0002 e I2=70%), needing to treat 33 patients to obtain this harm (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forest-plots of the analyzed outcomes

Anastomotic Leak

Twelve primary studies analyzed the anstomotic leak outcome. The incidence of anastomotic leak was 7,13% in the group of stapled (60 of 842 patients) and 7,77% in the group of hand-sewn (65 of 837 patients). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (RD -0.00; CI 95% -0,03 a 0,02; p=0.77 e I2=48%).

Pulmonary complications

Six primary studies analyzed the pulmonary complications outcome. The incidence of pulmonary complications was 27,90% in the stapled group (77 of 276 patients) and 19,56% in the hand-sewn group (54 of 276 patients). The stapled increased the absolute risk of pulmonary complications in 8% (CI 95% 0,01 a 0,14; p<0,02 e I2=29%), needing to treat 12 patients to obtain this harm (Figure 2).

Cardiac complication

Five primary studies analyzed the cardiac complication outcome. The incidence of cardiac complication was 17,94% in the stapled group (47 of 262 patients) and 18,22% in hand-sewn group (47 of 258 patients). There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (RD -0.00; CI 95% -0,07 a 0,06; p=0,96 e I2=0%).

Blood Loss

Three primary studies analyzed the blood loss outcome. The average difference between groups was 12,21 (CI 95% 0,91 a 23,51; p<0,03 e I2=44%). So, stapled generated less blood loss when compared with hand-sewn (Figure 2).

Mortality

This outcome considered in ten primary studies covers hospital mortality and 30 days mortality. The incidence was 7,15% in stapled group (50 of 699 patients) and 4,27% in hand-sewn group (31 of 670 patients). The stapled increased the absolute risk of mortality in 3% (CI 95% 0,00 a 0,05; p<0,04 e I2=0%), needing to treat 33 patients to obtain this harm (Figure 2).

Surgical time

Six primary studies analyzed the surgical time outcome. The average difference between the groups was 5,18 (CI 95% 4,07 a 6,29; p<0,00001 e I2=99%). So the stapled dismissed less surgical time when compared with hand-sewn (Figure 2).

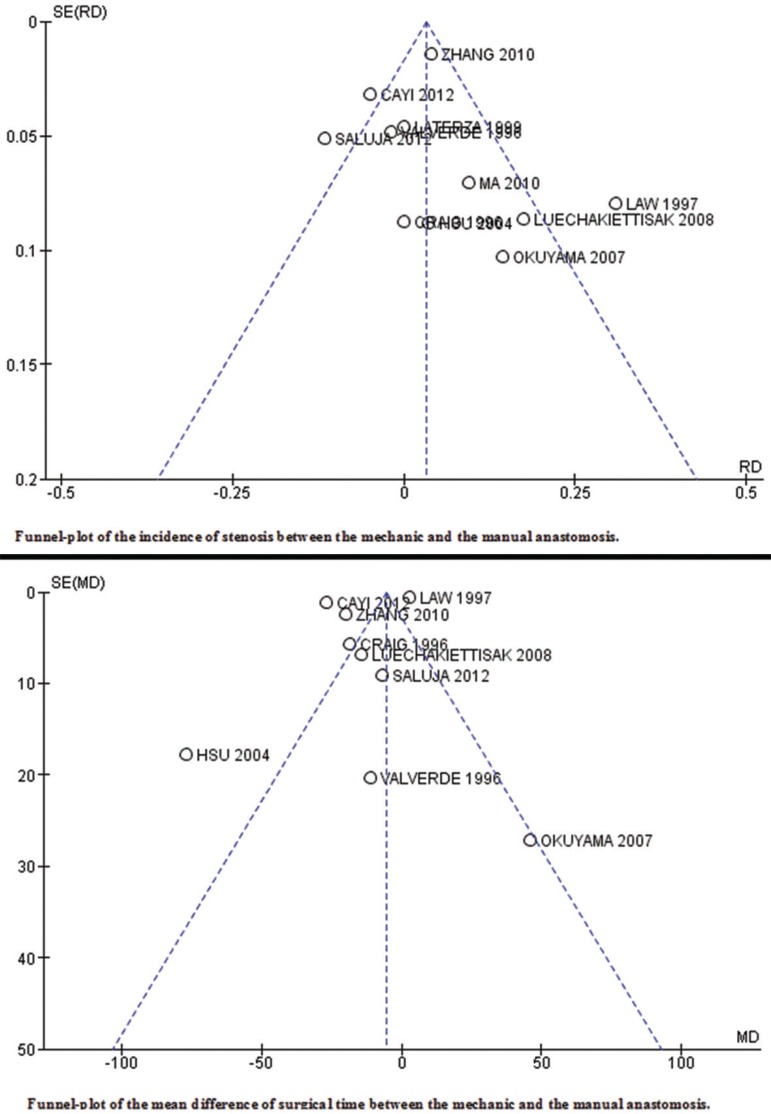

Each one of the funnel-plots of outcomes analyzed are represented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Funnel-plots of the outcomes that presented heterogeneity above than 50%

DISCUSSION

In 1960, at the Scientific Research Institute of Experimental Surgical Apparatus and Instruments in Moscow, a tubular instrument was devised to perform end-to-end anastomosis in the gastointestinal tract, where they can be technically difficult, such as low rectal anastomosis, esophagogastric or esophagojejunal anastomosis. The instrument creates an inverting anastomosis held by a double staggered row of stainless steel wire staples creating an anastomosis 21.2 mm internal diameter with no significant inverted flange.21

Some authors have shown that prolonged surgery time due to extension esophageal resection can relate to Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), sepsis, intraoperative hemodynamic instability and this proved difficult to a proper healing of esophageal anastomosis.2,23

The majority of tumors classified as surgical are localized at middle and distal thoracic esophagus or at esophagogastric junction. In these cases the technique most used in the world is Ivor Lewis16 chest abdominal esophagogastrectomy followed by Orringer20 transhiatal esophagectomy (abdominal-cervical) and, less frequently by thoraco-abdomino-cervical technique.7

Systematic review and meta-analysis is a type of study of scientific accuracy for selecting the best avaible evidence in the medical literature, but should also assess the methodological quality of primary studies. This is necessary to obtaining accurate conclusions about the effect of interventions. To avoid distortions, it was decided to include only results with clinical and statistical homogeneity.

There are two systematic reviews in the literature about this topic: Urschel24 published in 2001 and Honda9 published in February 2013. The first includes five randomized controlled trials, counting with a total sample of 467 patients, being 231 in the hand-sewn group and 236 in the stapled group. This meta- analyses analized mortality, anastomotic leak, anastomotic sricture, cardiac and pulmonary morbidity. All the outcomes showed results statistically not significant. Already the second includes twelve randomized controlled trials, counting with a total sample of 1407 patients, being 692 in the hand-sewn group and 715 in the stapled group. This study evaluated anastomotic leak (not significant), anastomotic stricture (favorable to hand-sewn), surgical time (favorable to stapled), mortality after 30 days of surgery (not significant) and stapler diameter compared with anastomotic stricture.

In this review, the incidence of anastomotic stricture corresponds to 12,33% and 9,26% in groups of manual and mechanical anastomosis, respectively (CI95% 0,00 a 0,06; p<0,0002). Anastomotic leak occurred in 7,13% patients with mechanical anastomosis and 7,77% in manual (CI95% -0,03 a 0,02; p<0,77). Pulmonary complications were observed in 27,9% in mechanical anastomosis and in 19,56% in manual (CI95% 0,01 a 0,14; p<0,02). Regarding cardiac complications, 17,94% of patients with stapled and 18,22% with hand-sewn presented this outcome (CI95% -0,07 a 0,06; p<0,96). The mean difference of intraoperative blood loss was 12,21 (CI95% -23,51 a -0,91; p<0,03), demonstrating that the stapled promoted less blood loss when compared with hand-sewn. In relation to surgical time, the stapled needed less time to be executed when compared with hand-sewn, with a mean difference of 5,18 (CI95% -6,29 a -4,07; p<0,00001).

Comparing the three studies (Urschel, Honda and this review), in relation to anastomotic leak, all meta-analyses showed statistically not significant results. In the outcome of anastomotic stricture, Urschel showed result statistically not significant, while the other two studies pointed favoring manual anastomosis. In cardiac complications both Urschel and this study showed no significant difference between both methods. Already in pulmonary complications, this study unlike Urschel showed difference between the procedures, once the stapled increases its absolute risk. About the outcome of operative time both Honda and these study pointed favoring stapled. On the outcomes of mortality both Urschel and Honda showed statistically not significant results. Already this study showed that the mechanical anastomosis increased the absolute risk of mortality compared to the manual.

One study (Aquino1) presented in Hondas review, was not included in this study due it did not comtemplate the inclusion criteria, once esophagectomy was for esophageal achalasia and not for neoplasm.

Urschel and Honda reviews used the Risk Ratio (RR) in the meta-analysis that should not be used in therapeutic studies, since they distort both the analysis of data as its heterogeneity. In this review, was chosen to express the results in the form of NNT and NNH when the data were statistically significant, which express respectively the required number of patients who need to be treated to obtain benefit or harm in the outcome analyzed.

In this review Jadad12 scale was not used for critical assessment of the methodological quality of primary studies, because it includes blinding parameter. It is know that in studies of surgical punch cannot perform the blinding of the surgeon. Thus, the maximum Jadad scale in this type of study would be 3, which would limit the selection of included studies. The Urschel study used the Jadad scale, but omits the scores assigned to the paper. As well as this paper Honda recognizes the impossibility to perform the complete blinding.

One possible source of bias may be the differences between the processes of randomization of the included studies. However, the quality of the allocation process was considered adequate in all studies. All the patients analyzed had defined eligibility criteria. In statistical analysis, the calculation of sample size and analysis by intention to treat were used. A common limitation of the analysis of surgical time and length of hospital stay was the lack of statistical measures such as standard deviation or present continuous data as median and range.

The study followed all the ethical and confidentiality principles of information that are recommended. For dealing with analysis of results already published in other articles, was not required formal approval from a research ethics committee.

CONCLUSION

After resection of esophageal cancer, the use of stapler shown to reduce blood loss and surgical time, but increased the incidence of anastomotic stricture, pulmonary complications and mortality.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Financial source: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Aquino JL, Camargo JG, Said MM, Merhi VA, Maclellan KC, Palu BF. Avaliação da anastomose esofagogástrica cervical com sutura mecânica e manual em pacientes com megaesôfago avançado. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2008;35(5) doi: 10.1590/s0100-69912009000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aquino JLB, Lopes LR, Andreollo NA. Fraga G, Pereira GS, Lopes LR. Atualidades em Clinica Cirurgica.Intergastro e Trauma 2011. 2. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Atheneu; 2011. Fistulas e deiscências na cirurgia do esôfago; pp. 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia . Diretrizes metodológicas: elaboração de pareceres técnico-científicos. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2011. 79. (A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cayi R, Li M, Xiong G, Cai K, Wang W. Comparative analysis of mechanical and manual cervical esophagogastric anastomosis following esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2012 Jun;32(6):908–909. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig SR, Walker WS, Cameron EW, Wightman AJ. A prospective randomized study comparing stapled with handsewn oesophagogastric anastomoses. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41(1):17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. [Acesso em:10 de julho de 2013]. Disponível em: < www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/tiposdecancer/site/home/esofago/definicao> .

- 7.Gonzalez GL, Herrera MH, Padron JA, Justis EU. Anastomosis esofagogástrica látero-lateral con engrapadora lineal en la operación de Ivor Lewis. Rev Cub Med Mil. 2012;41(3):292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriques AC, Zanon AB, Godinho CA, Martins LC, Júnior R, Speranzini MB, Waisberg J. Estudo comparativo entre as anastomoses cervicais esofagogástricas término-terminal com e sem invaginação após esofagectomia para câncer. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2009;36(5) doi: 10.1590/s0100-69912009000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honda M, Kuriyama A, Noma H, Nunobe S, Furukawa TA. Hand-sewn versus mechanical esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2013 Feb;257(2):238–248. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826d4723. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD: 2010. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu HH, Chen JS, Huang PM, Lee JM, Lee YC. Comparison of manual and mechanical cervical esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection for squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004 Jun;25(6):1097–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim RH, Takabe K. Methods of esophagogastric anastomoses following esophagectomy for cancer: A systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2010 May;101(6):527–533. doi: 10.1002/jso.21510. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laterza E, de' Manzoni G, Veraldi GF, Guglielmi A, Tedesco P, Cordiano C. Manual compared with mechanical cervical oesophagogastric anastomosis: a randomised trial. Eur J Surg. 1999 Nov;165(11):1051–1054. doi: 10.1080/110241599750007883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Law S, Fok M, Chu KM, Wong J. Comparison of hand-sewn and stapled esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection for cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 1997;226(2):169–173. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199708000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis I. The surgical treatment of carcinoma of the oesophagus with special reference to a new operation for growths of the middle third. Br J Surg. 1946;34:18–31. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003413304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luechakiettisak P, Kasetsunthorn S. Comparison of hand-sewn and stapled in esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal cancer resection: a prospective randomized study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(5):681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma RD, Zhang WT, Xu QR, Chen LQ. Esophagogastrostomy by side-to-side anastomosis in prevention of anastomotic stricture: a randomized clinical trial. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010;48(8):577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okuyama M, Motoyama S, Suzuki H, Saito R, Maruyama K, Ogawa J. Hand-sewn cervical anastomosis versus stapled intrathoracic anastomosis after esophagectomy for middle or lower thoracic esophageal cancer: a prospective randomized controlled study. Surg Today. 2007;37(11):947–952. doi: 10.1007/s00595-007-3541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orringer MB, Sloan H. Esophagectomy without thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;76:643–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravitch MM, Steichen FM. A stapling instrument for end-to-end inverting anastomoses in the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg. 1979;189(6):791–797. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197906000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saluja SS, Ray S, Pal S, Sanyal S, Agrawal N, Dash NR, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Randomized trial comparing side-to-side stapled and hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomosis in neck. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(7):1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thornton FJ, Barbul AC. Cicatrização no trato gastrointestinal. Clin Cir Am Norte. 1997;3:547–570. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urschel JD, Blewett CJ, Bennett WF, Miller JD, Young JE. Handsewn or stapled esophagogastric anastomoses after esophagectomy for cancer: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14(3-4):212–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valverde A, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Elhadad A. Manual versus mechanical esophagogastric anastomosis after resection for carcinoma: a controlled trial. French Associations for Surgical Research. Surgery. 1996;120(3):476–483. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walther B, Johansson J, Johnsson F, Von Holstein CS, Zilling T. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophageal resection and gastric tube reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial comparing sutured neck anastomosis with stapled intrathoracic anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238(6):803–812. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098624.04100.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West of Scotland and Highland Anastomosis Study Group. Suturing or stapling in gastrointestinal surgery: a prospective randomized study. Br J Surg. 1991;78(3):337–341. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Worrell S, Mumtaz S, Tsuboi K, Lee TH, Mittal SK. Anastomotic complications associated with stapled versus hand-sewn anastomosis. J Surg Res. 2010;161(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang YS, Gao BR, Wang HJ, Su YF, Yang YZ, Zhang JH, Wang C. Comparison of anastomotic leakage and stricture formation following layered and stapler oesophagogastric anastomosis for cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(1):227–233. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]