Abstract

Mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids are steroid hormones that are released by the adrenal cortex in response to stress and hydromineral imbalance. Historically, adrenocorticosteroid actions are attributed to effects on gene transcription. More recently, however, it has become clear that genome-independent pathways represent an important facet of adrenal steroid actions. These hormones exert nongenomic effects throughout the body, but a significant portion of their actions are specific to the central nervous system. These actions are mediated by a variety of signalling pathways, and lead to physiologically meaningful events in vitro and in vivo. Here we review nongenomic effects of adrenal steroids in the central nervous system at the levels of behaviour, neural system activity, individual neurone activity, and subcellular signalling activity. A clearer understanding of adrenal steroid activity in the central nervous system will lead to a better ability both to treat human disease, and to reduce side-effects of steroid treatments already in use.

Keywords: glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, adrenal, nongenomic, HPA axis

Introduction

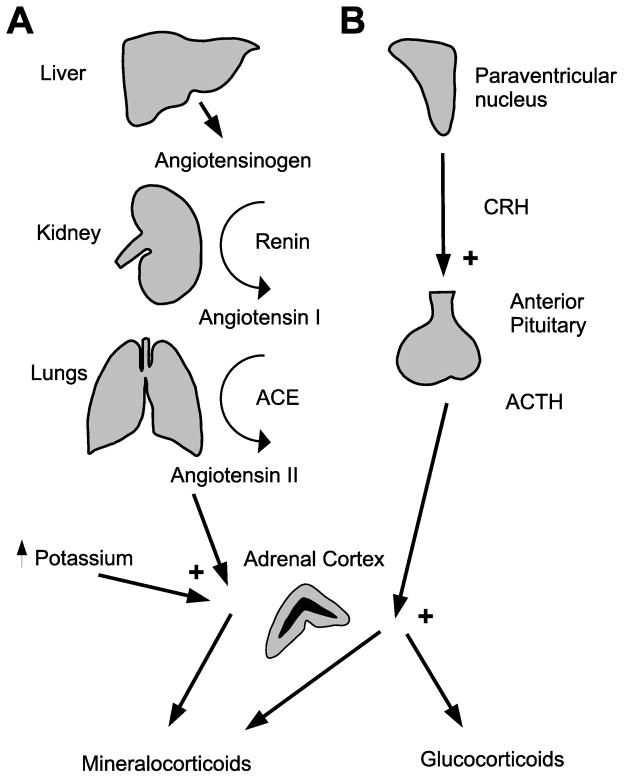

The adrenal gland is a major producer of hormones involved in the stress response (catecholamines (mainly epinephrine) from the medulla and glucocorticoids from the cortex) and hydromineral balance (mineralocorticoids from the cortex). Both glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids are steroids that are released in response to stimulating hormones (Figure 1). ACTH stimulates the synthesis and release of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. Mineralocorticoid synthesis is also stimulated by angiotensin II and blood potassium levels.

Figure 1.

Regulation of adrenal steroid production. A) Mineralocorticoids: angiotensinogen produced in the liver is converted to angiotensin I by the kidney. Angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II in the lungs, and acts on the adrenal cortex to induce aldosterone production. In addition, increased plasma potassium concentration causes increased aldosterone production. B) Glucocorticoids: CRH released by the PVN causes release of ACTH from the anterior pituitary. ACTH acts on the adrenal cortex to stimulate production of glucocorticoids and, to a lesser extent, aldosterone.

Adrenal steroids have widespread effects in the body. Glucocorticoids are secreted in response to stress, and affect multiple organ systems (1). Mineralocorticoids are secreted in response to sodium deficit or potassium excess and maintain hydromineral balance by acting on the nervous system and on renal and vascular tissues. Historically, the effects of these steroid hormones were thought to be mediated by canonical nuclear steroid receptor signalling. Upon ligand binding, the receptors translocate to the nucleus of the cell, and regulate gene transcription either by binding to response elements in gene promoters or interacting with other transcription factors.

An ever-growing literature indicates that adrenal steroids can also have rapid, non-genomically mediated effects on end organs. It is increasingly clear that nongenomic adrenal steroid-mediated signalling is not artifactual, but rather represents physiologically important signalling. This review focuses on the current state of knowledge regarding nongenomic adrenal steroid signalling, especially in the central nervous system.

Non-genomic Signalling by Adrenal Steroids

Much of our knowledge about non-genomic actions of adrenocorticosteroids, particularly mineralocorticoids, originates from studies on non-neural tissue. Information gained from studies of nongenomic steroid effects in extra-neural tissues is important for understanding neuronal actions, given that many of the same signalling pathways are likely to be operating in both neural and non-neural tissues.

Mineralocorticoids: Ions in flux

Following the initial characterization of mineralocorticoids, Ganong and Mulrow (2) examined sodium and potassium excretion of adrenalectomised dogs after intra-arterial injections of aldosterone. Less than 5 min post-injection, aldosterone decreased renal sodium excretion, demonstrating for the first time that this steroid has rapid effects in vivo (2). Similarly, Klein and Henk (3) found that 5 min after aldosterone administration vascular resistance and blood pressure was elevated in men. Subsequently, an in vitro study revealed that physiological concentrations of aldosterone decreased sodium exchange in canine erythrocytes, an effect that was necessarily non-genomic due to the lack of nuclei in these cells (4). Taken together, this pioneering research suggested that aldosterone has rapid, presumably non-genomic effects on renal and cardiovascular function.

Despite these early observations, the non-genomic paradigm was not significantly advanced until Moura and Worcel (5) investigated the effects of aldosterone on sodium efflux from arterial smooth muscle. In this study, physiological concentrations of aldosterone had both rapid and delayed effects on transmembrane 22Na efflux ex vivo. Aldosterone administration increased 22Na efflux within 15 min, which was followed by a secondary rise in efflux that peaked 4 hours later. In contrast to the late rise in 22Na efflux, the early increase was unaffected by inhibition of gene transcription via actinomycin D. Activation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) with supramaximal doses of RU 26988, a selective GR ligand, failed to produce changes in 22Na efflux. However, both early and late effects of aldosterone on 22Na efflux could be blocked by treatment with mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonists RU 28318 or spironolactone. These result suggested that the rapid effects of aldosterone on transmembrane 22Na efflux are not only non-genomic, but dependent on activation of classical MR.

Subsequent work by the Wehling laboratory provided compelling evidence for non-genomic actions of aldosterone. Application of aldosterone to human mononuclear leukocytes rapidly induced swelling by 30–50% at concentrations as low as 0.07 nM. This effect was attributed to increased activity of membrane Na+-H+ exchanger and was not blocked by actinomycin D or the MR antagonist potassium canrenoate (6). Also, the effect was specific to aldosterone because corticosterone, dexamethasone, and cortisol were 1000-fold less effective at eliciting a similar response. The authors concluded that these effects are not attributable to the steroid-receptor interacting with nuclear DNA because the effect on the Na+-H+ exchanger occurs too quickly. Rather, it is likely that aldosterone has rapid direct effects on cell membranes by binding to novel receptors because the classical MR antagonists, potassium canrenoate, have no effect on mononuclear leukocyte swelling.

Glucocorticoids

Historically, the most important pharmacological use of glucocorticoids has been in immunosuppression. Many aspects of the immunosuppressive action of glucocorticoids, such as inhibition of cytokine gene expression, are explained by genomic actions (7). However, there are other effects, including rapid effects on second messenger systems and cell membranes in immune cells, that are most likely mediated by nongenomic actions (8, 9). These changes are thought to lead to observed rapid anti-inflammatory effects of high-dose steroid treatment (10). In addition to these effects in the immune system, nongenomic glucocorticoid effects have been documented in cells from other peripheral tissues, including endometrium (11), lung (12, 13), liver (14), intestine and kidney (15).

Non-genomic effects of Adrenal Steroids in the Nervous System: behaviour and physiology

There is a growing body of literature outlining nongenomic effects of mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids in the central nervous system. Both of these hormones exhibit nongenomic effects on multiple aspects of neural function.

Mineralocorticoids: Behaviour (Salt Appetite)

Research evaluating non-genomic actions of aldosterone on behavioural responses to sodium deficit provides indirect evidence of aldosterone modulation of neuronal function. Aldosterone binds to MR receptors in the forebrain, where it acts synergistically with angiotensin II to cause the arousal of one of the most fundamental motivated behaviours, salt appetite. This appetite is specific for sodium salts and is quickly sated when the deficit is alleviated. Traditionally, aldosterone is thought to arouse salt appetite by altering the expression of targeted genes. However, steroid hormones can rapidly elicit behaviours through non-genomic actions. For example, aldosterone implanted into the medial amygdala (200 μg) elicited salt intake less than 15 min after administration (16). However, when saline was presented to the animals 24 h after central aldosterone administration an increased intake was not observed. Rapidly induced consumption of saline is specific to mineralocorticoids because comparable intake was not observed with co-administration of the GR agonist, RU 28362. Moreover, appetite is restricted to sodium solutions, as central aldosterone administration did not increase consumption of water or of a palatable glucose solution (16).

Non-genomic effects of aldosterone may also be mediated through steroid metabolites. Tetrahydro-derivatives (A-ring reduced forms) of aldosterone elicit sodium appetite (16) (17). Injection of aldosterone, deoxycorticosterone (DOCA), or tetrahydro-aldosterone into the medial amygdala rapidly elicits sodium intake that is not affected by prior application of antisense oligonucleotides or antagonists targeting MR (17). Rather, salt appetite induced by tetrahydro-aldosterone is inhibited by GABA receptor antagonists Ro15-04513 or Ro15-1788, but mimicked by GABA agonist flunitrazepam (16, 17). Taken together, these studies suggest that the rapid arousal of salt appetite may be due to the local conversion of aldosterone to its tetrahydroderivative, which in turn activates GABAA receptors.

The synergy hypothesis revisited

It was hypothesised that aldosterone and angiotensin II work in concert to arouse sodium appetite because circulating levels of these hormones are concurrently elevated during sodium depletion (18). Fluharty and Epstein (19) found that simultaneous administration of angiotensin II and DOCA produce a salt intake that is greater than the sum of the amounts consumed when the same doses are administered separately. Furthermore, low doses of angiotensin II and DOCA that are ineffective at evoking salt appetite when given independently become potent at inducing sodium intake when given at the same time. The synergistically-enhanced salt intake is believed to be due in part to aldosterone-induced up-regulation of angiotensin type I receptors (AT1R), since chronic administration of DOCA increases angiotensin II-receptor binding sites in tissue homogenates (20) as well as in specific brain regions (21, 22). Recent studies have found that angiotensin II-induced salt appetite is dependent on AT1R-induced activation of MAPK (23). Specifically, central administration of an AT1R agonist that selectively activates MAPK rapidly (<15 min) induces salt intake (23). Interestingly, aldosterone increases Na+-H+ exchange by activating MAPK through a non-genomic mechanism (24). The ability of both aldosterone and angiotensin II to activate MAPK suggests a mechanism whereby they may have additive effects, although the synergy that has been observed between the two suggests that other pathways may be involved as well.

Mineralocorticoids: membrane current/neuronal activity

Aldosterone rapidly influences the movement of various ions across the plasma membrane by activating second messenger systems. In patch clamp studies, aldosterone (1–10 nM) increases Na+/K+/2Cl− transporter activity, which raises intracellular [Na+] and augments Na+-K+ pump activity, thereby producing a rapid (<15 min), 10-fold increase in current across the plasma membrane (25). These rapid effects are not blocked by actinomycin D, canrenoate or spironolactone administration, but are inhibited by elimination of Na+ influx. A possible role for protein kinase C (PKC) was investigated because previous studies found that aldosterone activates this protein kinase (26) (27), which in turn has been found to modulate Na+/K+/2Cl− transporter and Na+-K+ pump activity (28). Accordingly, aldosterone regulation of Na+/K+/2Cl− transporter and Na+-K+ pump activity is blocked by εPKC antagonists, but mimicked by εPKC agonists (29).

Membrane effects of MR are evident in the mouse hippocampus. Aldosterone and corticosterone act through MR to rapidly increase the frequency of miniature excitatory post-synaptic potentials (30). These effects are mediated through the ERK1/2 pathway (31). These results suggest that aldosterone-induced activation of second messenger systems rapidly affects membrane current and therefore has the potential to alter the generation of action potentials in these cells.

Glucocorticoids: Behavioural

Similar to mineralocorticoids, glucocorticoids rapidly elicit behavioural changes, consistent with nongenomic signalling in the central nervous system. The best characterised behavioural effects of glucocorticoids are observed in the amphibian Taricha granulosa, in which acute administration of glucocorticoids induces the sexual clasping behaviour (32). Cortisol increases the duration of fictive vocalization activity in the Midshipman fish (Porichthys notatus) within 5 minutes. This action is blocked by RU486 treatment, and appears to be mediated by the brainstem or spinal cord of the fish (33). Nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids have also been described in avian species. For example, in the white crowned sparrow, corticosterone increases locomotor activity within 15 minutes of administration (34). Other work done with the migratory Red Knot is consistent with rapid effects of corticosterone on locomotor activity, although more work is necessary to confirm that these effects are nongenomic (35).

In addition to non-mammalian species, there have been reports of possible or probable non-genomic actions of glucocorticoids in rats. Novelty-related locomotor activity in rats is increased in a nongenomic fashion by corticosterone treatment (36). This increase in activity may relate to risk-assessment behaviour, which is rapidly increased after treatment with corticosterone, without change in anxiety-like behaviour or general locomotion (37). Similarly, corticosterone administered systemically or intracerebroventricularly increases aggression in rats within less than 10 minutes, an effect that is not blocked by cycloheximide (38, 39). Corticosterone rapidly inhibits the acoustic startle response in rats (40). Also, intrathecal injection of RU486 into rats with spinal cord injury decreases the hyperalgesic effects of the lesion within 30 minutes (41), consistent with a putative nongenomic glucocorticoid signalling pathway. In this same study, hyperalgesic effects were initiated by NMDA agonism and reversed by glucocorticoid antagonist treatment, suggesting a possible interaction between the NMDA receptor system and the glucocorticoid signaling pathway. Finally, glucocorticoid treatment rapidly inhibits retrieval of long-term memory, in a manner that is insensitive to protein synthesis inhibition (42). There is also evidence for a rapid, presumably nongenomic role for glucocorticoids in regulating feeding at the hypothalamus (43). These results suggest that nongenomic glucocorticoid signalling may be involved in an array of behavioural responses in diverse species of animals, consistent with nongenomic effects of these hormones on neuronal systems.

Glucocorticoids: HPA Axis

Glucocorticoids are known to exert nongenomic feedback effects on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is a main component of an organism’s response to experiences that threaten or potentially threaten an animal’s homeostasis (1), and is responsible for secretion of glucocorticoids. Like other endocrine axes, the HPA axis is regulated in part by negative feedback inhibition of the axis by glucocorticoids. Although part of this negative feedback is mediated by classical steroid receptor signalling, it is also clear that rapidly-induced negative feedback inhibition of the axis can be mediated by nongenomic glucocorticoid signalling. Figure 2 outlines HPA axis organization as well as some sites at which negative feedback occurs.

Figure 2.

Negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis. Glucocorticoid secretion is under control of the HPA axis. CRH secreted by the PVN causes release of ACTH from the anterior pituitary, which acts on the adrenal cortex to induce the production of glucocorticoid hormones. The PVN is under higher control from a number of other parts of the brain (dashed arrows; for review, see (127)). Glucocorticoids regulate activity of the HPA axis through negative feedback on multiple levels. Fast feedback occurs at the hypothalamus and pituitary glands (solid arrows). Negative feedback occurs on longer time scales at other parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, paraventricular thalamus, lateral septum, and prefrontal cortex (dotted arrows). It is possible that fast feedback signalling by glucocorticoids occurs at these brain areas as well, but this has not yet been tested.

Some of the earliest evidence for fast feedback inhibition of the HPA axis by glucocorticoids was published in the late 1940s, by Sayers and Sayers (44). Treatment of rats with adrenal extract five minutes before initiation of an epinephrine infusion blocked the decrease in adrenal ascorbic acid content (an indirect index of corticosterone production) at 30 minutes after the beginning of the epinephrine infusion, indicative of decreased corticosterone synthesis Since then, evidence has accumulated that nongenomic negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis by glucocorticoids occurs at the anterior pituitary gland. In vitro work has shown that corticosterone inhibits CRH-induced ACTH release from cultured pituitary explant fragments within less than 20 minutes (45), suggesting a nongenomic mechanism of action. In cultured pituicytes, this inhibition persists in the presence of cycloheximide, further evidence that this inhibition represents a nongenomic action of glucocorticoids (46).

Also in the early 70s more evidence emerged that glucocorticoids rapidly alter the HPA axis response to stressors. Bilaterally adrenalectomized rats rapidly increase ACTH and then maintain high ACTH levels in response to the surgery, while sham-operated animals rapidly return to baseline ACTH levels (47). ACTH levels in sham-operated animals return to baseline as corticosterone levels increase. The elevation in ACTH in adrenalectomized animals is prevented by administering corticosterone at the time of laparotomy, suggesting that there is a rapid effect of corticosterone on ACTH release.

In addition to in vitro studies, there is in vivo evidence for nongenomic glucocorticoid actions at the pituitary. Rats with mediobasal hypothalamus lesions, which destroy the afferent connections from the brain to the pituitary, display rapid inhibition of ACTH release in response to corticosterone treatment (48). Furthermore, glucocorticoids rapidly inhibit CRH-induced ACTH secretion in anaesthetised rats (49). This effect persists despite prior actinomycin D treatment, implicating a nongenomic signalling pathway. These data strongly suggest that nongenomic negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis occurs at the level of the pituitary gland.

The hypothalamus is also a site for nongenomic glucocorticoid negative feedback. Glucocorticoids rapidly inhibit CRH release from hypothalamic slices (48, 50) and synaptosomes (51). In vivo, treatment of rats with corticosterone within 2 minutes after adrenalectomy inhibits the decrease in hypothalamic CRH, suggesting a rapid inhibitory action on CRH release by glucocorticoids (52). Treatment with dexamethasone or corticosterone, but not cholesterol or isopregnanolone rapidly decreases the frequency of excitatory post synaptic currents in CRH-containing hypothalamic cells (53). Inhibition of glutamate release suggests a rapid inhibitory action of glucocorticoids on CRH release. Furthermore, infusion of dexamethasone directly into the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of rats 5 minutes before restraint stress blunts the ACTH and corticosterone responses (Evanson and Herman, unpublished results). This suppression of HPA activation is also caused by dexamethasone covalently bound to bovine serum albumin (dex:BSA), thus implicating a membrane glucocorticoid receptor in the nongenomic feedback signalling pathway. Taken together, these studies suggest that fast feedback inhibition of the HPA axis occurs via signalling at the PVN as well as at the pituitary.

Other parts of the brain have not yet been implicated in fast, nongenomic feedback inhibition of the HPA axis. However, because other brain areas, including the hippocampus (54, 55), prefrontal cortex (56) paraventricular thalamus (57), and lateral septum (58) are known to be involved in negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis, it is reasonable to expect that at least some of these areas may be involved in negative feedback through nongenomic signalling. In addition, there is evidence that glucocorticoids can increase CRH levels in the amygdala in a manner that is rapid (<30 min) and mirrors the increase in plasma and amygdalar cortisol, suggesting that this change in CRH content may be mediated by a nongenomic signalling pathway for cortisol (59). It is as yet unclear whether this represents control of HPA axis activity through the amygdala, however. Further studies are needed to explore this possibility.

Electrophysiology/neuronal activity

There is a wealth of information available about rapid effects of glucocorticoids on neurone electrophysiology. Glucocorticoids rapidly exert both excitatory and inhibitory influences on neurones in the hypothalamus (60–62), hippocampus (30, 61, 63, 64), and brainstem (60, 61) in rodents. These effects appear between milliseconds and about 30 minutes after application of glucocorticoids, suggesting nongenomic actions. In addition, because the hippocampus and hypothalamus are involved in regulation of the HPA axis, these effects on neuronal excitability may be involved in nongenomic negative feedback.

These effects could be caused by the action of glucocorticoids on ion channels or membranes (see below) or via modulation of neurotransmitter systems. Corticosterone rapidly increases both aspartate and glutamate levels in the hippocampus (65). Glucocorticoid treatment also rapidly increases glutamate uptake into hippocampal synaptosomes (66) and tryptophan uptake into whole brain synaptosomes (67), suggesting that some of the nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids on neuronal signalling may be through effects on neurotransmitter metabolism.

Signalling Mechanisms

There is a great deal of information available about receptors and intracellular signalling pathways that are involved in the nongenomic effects of adrenal steroids. One of the major questions that remains open, with respect to the receptors that are operative in nongenomic effects of these steroids, is whether the effects are mediated by the classical intracellular receptors GR and MR (whether in the normal intracellular form, or as a modified, membrane-associated version) or by novel, as yet unidentified receptors. There are data supporting both of these positions. Also, there is a great deal of data about signalling pathways that are involved in mediating the effects of nongenomic adrenal steroid signalling.

Receptors mediating nongenomic adrenal steroid effects

Mineralocorticoids: Membrane Bound vs. Classical Intracellular Receptors

Although studies by the Wehling laboratory and others support the existence of a novel membrane receptor that mediates the rapid effects of aldosterone, it should be noted that there is evidence that these effects may occur through activation of the classical MR. As mentioned previously, rapid effects of aldosterone on 22Na efflux and Na+-H+ exchange can be blocked by MR antagonists (5, 68). It is possible that novel membrane receptors bind RU28318 or other MR antagonists and this may account for the inhibition of non-genomic effects, although the fact that inhibition of 11β-HSD permits cortisol to induce rapid effects on cell physiology similar to those of aldosterone argues against this possibility. Specifically, low dose aldosterone rapidly stimulates mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) and Na+-H+ exchanger activity, but cortisol fails to produce these effects even at concentrations 100-fold higher (68, 69). However, when 11β-HSD is inhibited by pretreatment with carbenoxolone, cortisol becomes a strong agonist rapidly eliciting stimulation of both MAPK and Na+-H+ exchanger at doses similar to that of aldosterone (68, 69). These effects are likely not mediated by membrane receptors because 11β-HSD is a cytosolic enzyme that prevents the binding of glucocorticoids to MR. Taken together, these studies suggest that the non-genomic effects of aldosterone can occur through novel activation of classical MR.

Glucocorticoids

More is known about the receptors mediating nongenomic glucocorticoid effects than about those mediating nongenomic mineralocorticoid effects. The evidence unearthed so far suggests that nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids can be classified three ways, based on receptors mediating these effects: 1) effects not mediated by a receptor, 2) effects mediated by the cytosolic GR, and 3) effects mediated by a membrane-bound receptor.

Non-receptor mediated

Non-receptor mediated glucocorticoid signalling consists mainly of specific, direct effects of steroid hormones on cell membranes. Sex steroids, for example, can alter membrane fluidity and permeability to hydrophilic molecules, as well as inducing membrane vesicle fusion (70, 71). Cortisol can increase membrane fluidity, while progesterone decreases it (72). In fact, membrane effects of individual steroids even show specificity for membrane preparations from different organs, such as brain vs. muscle (71).

Alterations in the physicochemical properties of the plasma membrane could change the activity of membrane-bound proteins (73), or result in altered permeability of the membrane to ions (10). Direct effects of glucocorticoids on cell membranes are hypothesised to mediate some of the rapid therapeutic effects of glucocorticoids, such as that achieved by pulse glucocorticoid treatment of severe inflammatory disorders (10, 74). Indeed, direct effects on permeability of the mitochondrial membrane may underlie the induction of apoptosis by glucocorticoids in immune cells (75). These results suggest that physicochemical interactions of steroids with cell membranes may be important mediators of the pharmacological effects of steroids. The high concentration of steroids used in pulse glucocorticoid therapies, suggests that this may not be an important physiological steroid signalling pathway; however, it does represent an important pharmacological pathway, as the concentrations used are therapeutically relevant.

Cytosolic GR

Nongenomic actions of glucocorticoids mediated through the classical, cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor (GR) are suggested by the association of kinases, such as Src, with the GR complex in the cytoplasm of the cell (8). Binding of glucocorticoids to GR leads to dissociation of other proteins in the complex from GR (76). In the case of Src and other putative signalling molecules operating nongenomically through the cytosolic GR, dissociation of the kinase from the GR complex would free it to phosphorylate its targets, and thus to mediate nongenomic signalling. In support of this putative signalling pathway, oestrogen is known to signal through Src (77). This Src-mediated signalling involves the scaffold protein MNAR/PELP, which is extensively co-expressed with GR in the nervous system (78), suggesting that GR may signal through a similar pathway. Similarly, GR can form part of the protein complex that includes the T-cell receptor. Binding of glucocorticoids to GR causes dissociation of this complex, and thus leads to impaired signalling through the T-cell receptor (79).

Membrane-bound Receptors

Although cytosolic GR may be involved in nongenomic glucocorticoid signalling, in many cases the receptor mediating nongenomic effects is apparently membrane-bound. Early evidence for this conclusion was supplied by studies revealing corticosteroid binding to brain cell membranes in vitro (80). Assays comparing the binding of oestrogen, progesterone, testosterone, and corticosterone suggested that there are distinct binding sites for each of these steroids. None of these hormones is able to compete with the others at their respective binding sites, indicating that there are specific receptors for each steroid. Plasma membrane binding sites for glucocorticoids in synaptic membranes and pituitary cells often have characteristics that are compatible with these sites being G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)(53, 81–83). However, there is also evidence of other membrane receptors, such as the GABAA receptor, that mediate some of the nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids. Thus, we subdivide the classification of membrane-bound receptor-mediated effects into three types: effects mediated by a membrane-bound form of GR, effects mediated by a membrane bound, non-GR glucocorticoid receptor, and effects mediated by interactions with proteins that are not primarily glucocorticoid receptors.

Membrane-bound glucocorticoid receptors: GR or non-GR?

Although the presence of receptors for glucocorticoids in the membranes of cells is relatively undisputed, the identity of the membrane receptor is still unknown. There is a great deal of evidence supporting a form of GR as the receptor through which nongenomic effects are mediated, especially in the immune system. A presumably modified version of the classical GR has been identified by immunocytochemistry as being bound to the membrane of immune cells (84, 85). Membrane-bound GR is associated with a specific alternative transcript of GR (86), and appears to mediate at least some of the rapid effects of glucocorticoids in these cells (9, 87). GR has been identified in caveolae in the cell membrane (88), where it can elicit transcriptional signalling. It is not currently clear whether this caveolae-associated GR is also able to mediate nongenomic signalling, but this seems likely given that caveolae are membrane specializations associated with signal transduction, including GPCR-mediated signalling (89). Furthermore, GR has been shown by yeast two-hybrid screening to directly interact with G protein beta (90), and by co-immunoprecipitation to interact with the guanine exchange factor Brx (91). Dexamethasone causes rapid phosphorylation of ZAP kinase (87), and GR interacts with this kinase (92). In aggregate, it appears that nongenomic glucocorticoid signalling in the immune system is usually mediated by a membrane-associated form of GR (however, see ref. (93). This is in contrast to liver cells, in which the membrane part of the signalling cascade is apparently a steroid transport protein, which ties into GR signalling intracellularly (14, 94).

In the nervous system, current evidence suggests that a number of nongenomic and putative nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids are mediated by receptors other than GR. For example, hippocampal cells cultured so as to eliminate GR expression retain their ability to rapidly activate signalling through intracellular kinase cascades in response to acute glucocorticoid treatment (95). Also, many of the described nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids in the central nervous system are insensitive to inhibition by the GR antagonist RU38486 (53, 83, 96). Finally, aldosterone treatment of awake rats rapidly inhibits basal corticosterone secretion. This effect is blocked by the MR antagonist sodium canrenoate but not by RU486, suggesting that this effect on basal corticosterone secretion is mediated by MR (97). Together, these results appear to support the existence of a receptor other than GR, which mediates nongenomic actions of glucocorticoids.

As a caveat to this conclusion, there is some evidence that higher concentrations of RU38486 are able to at least partially antagonise effects that were not sensitive to inhibition at lower doses used in other studies (98). This could be caused by an alteration in the conformation of GR occurring due to membrane binding per se, or because of structural alterations necessary to allow a membrane localization of the receptor. For example, altering the hydrophobicity of an enzyme’s environment can significantly modify the activity or other chemical properties of the protein (73, 99). In fact, altering the lipid content of brain cell membranes through treatment with phospholipase C or A2 can abolish the binding of corticosterone to the membranes (80). These data suggest that changing the location of GR to the cell membrane could be sufficient to alter the affinity of the receptor for ligand and inhibitors.

That said, a membrane-bound, non-GR GPCR-associated receptor for corticosterone has been partially characterised in the salamander Taricha granulosa (100). Based on physical characteristics of the partially purified protein, this receptor is most likely an acidic glycoprotein, with a size of about 63 kilodaltons. The physical and chemical characteristics of this protein are dissimilar to the classical GR, although the possibility that the protein is a modified form of GR has not been unequivocally ruled out. Binding of corticosterone to this receptor is insensitive to RU38486 (32) and appears to mediate the behavioural effects of corticosterone on sexual clasping behaviour in this animal (101, 102). Interestingly, the rapid behavioural effects mediated through the Taricha membrane receptor appear to be regulated by endocannabinoid signalling (103), similar to the rapid inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on CRH-containing neurones in the hypothalamus (53). This receptor has not been cloned, and there is not yet any known homologue for it in mammalian systems.

Another possibility is that some of the nongenomic actions of glucocorticoids are mediated through a GPCR-associated receptor for a neurosteroid or similar molecule. A recent paper reported a GPCR-associated receptor for the neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (104), which also has affinity for corticosterone. Corticosterone binding to this receptor antagonised the effects of DHEA, suggesting that some of the nongenomic actions of glucocorticoids in the nervous system could occur by antagonizing actions of neurosteroids or other such signalling molecules.

In addition to evidence for non-GR protein involvement in nongenomic glucocorticoid actions, GR is expressed in the membranes of hippocampal and hypothalamic neurones (105). In the lateral amygdala, the presence of GR at post-synaptic membranes and in astrocytic processes has been demonstrated by electron microscopy (106). In addition, several synaptic proteins, including Vesl-2, LIM, and SH-3, have been identified as interacting with GR (107). Binding of GR to these proteins implies a mechanism by which GR could be localised to the synapse, where it could be involved in rapidly altering synaptic signalling.

Non-glucocorticoid-receptor membrane proteins

Alternatively, glucocorticoids may have rapid effects in the mammalian brain by acting directly on ion channels. For example, some steroids, especially neurosteroids, directly bind to and modulate the activity of the GABAA receptor (108, 109). Although glucocorticoids most likely do not have a strong influence on the GABAA receptor (108), some of the neurosteroids that do have this effect are products of glucocorticoid metabolism in the brain. Therefore, glucocorticoids could have nongenomic effects on GABA transmission indirectly, through metabolite actions. It is also possible that effects on ion transmission that have been attributed to non-receptor mediated glucocorticoid effects on cell membranes could be explained by this type of effect on ion channels.

Intracellular Signalling Systems

Mineralocorticoids

Studies performed by Gekle et al. were seminal in revealing signal transduction pathways initiated by aldosterone (110, 111). Aldosterone rapidly increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration of cultured Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK; (110)). The increase is specific to mineralocorticoids because application of hydrocortisone was only effective at doses 100-fold more concentrated. The mineralocorticoid-induced rise in Ca2+ is dependent on the entry of extracellular Ca2+ into the cell, but independent of aldosterone-induced changes in intracellular pH. Inversely, aldosterone mediated activation of Na+-H+ exchanger and the resulting cellular alkalinization is dependent on the entry of Ca2+ because omission of extracellular Ca2+ abolishes this effect. Thus, the aldosterone-elicited rise in intracellular Ca2+ is necessary for the rapid effects of the steroid on Na+-H+ exchanger. These studies demonstrate that Ca2+ serves as a second messenger that regulates the non-genomic actions of aldosterone on plasma membrane Na+-H+ exchange (110, 111).

Gekle et al. (110) also found that aldosterone rapidly elevates transmembrane proton conductance in MDCK cells through a mechanism that does not involve Na+-H+ exchanger and occurs in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. However, inhibition of H+ influx by application of Zn2+ prevents aldosterone-induced alkalinization, suggesting that the increased proton conductance enhances the activity of the Na+-H+ exchanger. It was subsequently reported that aldosterone-induced H+ influx is blocked by the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor calphostin C, but mimicked by application of phorbol esters or other activators of PKC (111). Based on these results the authors proposed that aldosterone stimulates G-protein-dependent activation of PKC, which in turn increases transmembrane proton conductance and enhanced activity of the Na+-H+ exchanger. Thus, aldosterone has the potential to rapidly influence cellular pH through two interrelated signalling mechanisms: 1) Ca2+ dependent activation of Na+-H+ exchanger and 2) PKC-mediated increase of H+ influx.

At the time that aldosterone-initiated signal transduction was being investigated researchers discovered that oestrogen interacts non-genomically with the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathway (112, 113). Given that the Na+-H+ exchanger is controlled by MAPK (114, 115), it is reasonable to hypothesise that non-genomic effects of aldosterone are mediated, in part, through the activity of this enzyme. Notably, inhibition of MAPK by pretreatment with PD 98059 or U 0126 prevents aldosterone-induced activation of Na+-H+ exchanger (24). Aldosterone elicits activation of MAPK through a non-genomic mechanism (24, 69), further supporting a central role for MAPK in non-genomic mineralocorticoid signalling, at least in terms of activation of the Na+-H+ exchanger. Importantly, aldosterone-induced activation of MAPK appears to be independent of the steroid’s effect on Ca2+ influx (24). Therefore, it is possible that aldosterone-induced activation of MAPK occurs upstream of Ca2+ influx or that the two events occur independently but simultaneously.

Glucocorticoids

Signalling pathways mediating nongenomic glucocorticoid actions have been exhaustively reviewed elsewhere (116, 117). Briefly, some of the systems implicated in these actions include endocannabinoids (53, 118–120), protein kinase A (13), protein kinase C (53, 96), mitogen activated protein kinases (9, 107), cAMP(11, 121), intracellular Ca2+ signalling(12, 121), phospholipase A2 (80, 122), phospholipase C (80, 121), and nitric oxide (40). Many of these pathways are generic intracellular signalling pathways, and could have effects in any cell type in which they are present. However, some of these pathways are of particular interest in the neuroendocrine system. For example, cannabinoids in the hypothalamus and the annexin 1 system in the anterior pituitary have both been implicated in nongenomic glucocorticoid regulation of HPA axis activity.

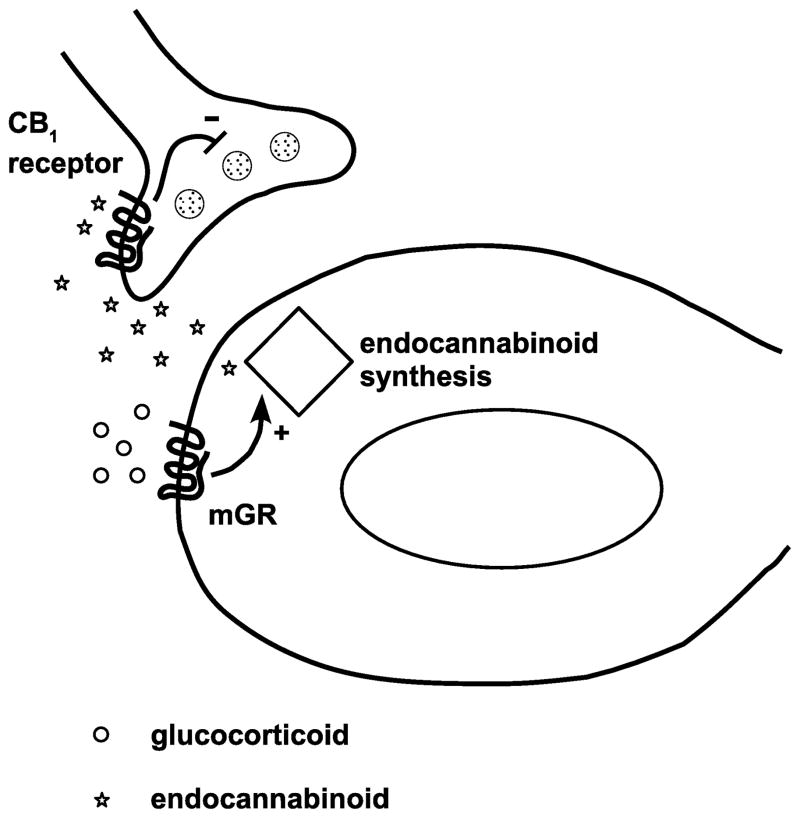

Endocannabinoid signalling is a common pathway for presynaptic regulation of neurotransmitter release in the brain (reviewed in (118, 119)). Coupled with the nearly ubiquitous expression of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in the brain (123–125), this presynaptic regulatory function suggests that glucocorticoids could cause nongenomic actions through endocannabinoid signalling. Indeed, there are several lines of evidence that link nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids on endocannabinoid systems to behaviour and neuroendocrine function. Effects of corticosterone on mating behaviour in Taricha granulosa appear to be mediated by endocannabinoid signalling (103). Acute or repeated restraint results in increased levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide in the amygdala and forebrain (126), both of which are implicated in regulating the HPA axis (127). In a hypothalamic slice preparation in which glucocorticoid treatment decreases glutamatergic inputs into CRH-containing neurones, the effects of glucocorticoids are blocked by treatment of the slices with the CB1 receptor antagonist AM-251 and mimicked by the agonist WIN 55,212-2 (53). In vivo, signalling through CB1 decreases the magnitude of the HPA response to stress (128), while antagonizing CB1 leads to an enhanced HPA response (129). In addition, CB1 knockout mice mount an enhanced ACTH and corticosterone response to novelty stress (120). These results support a role for cannabinoids in regulating the magnitude of an HPA axis response that is consistent with fast feedback control of the HPA response to stress (130). Figure 3 illustrates a recently proposed working model for glucocorticoid-endocannabinoid interaction in central control of the HPA axis (53).

Figure 3.

Endocannabinoid signalling in nongenomic feedback in the hypothalamus. Glucocorticoids act on a putative G-protein coupled receptor, by which they induce production of endocannabinoids in the postsynaptic neurone. Endocannabinoids act on CB1 receptors in the presynaptic terminal, which mediate decreased glutamate release onto the postsynaptic cell. Decreased glutamatergic inputs onto the CRH-containing postsynaptic cell leads to decreased CRH release and therefore to decreased HPA axis activity. mGR: membrane-associated glucocorticoid receptor. Adapted from (53).

The likely interaction between glucocorticoid signalling in the HPA axis and the endocannabinoid system, along with some of the described binding properties of GR suggests further refinement to this model for fast feedback signalling in the HPA axis. Endocannabinoid signalling is typically initiated by activation of a post-synaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor, which leads to the biosynthesis of endocannabinoids (131–133). The protein Vesl-2 (also known as Homer-2) binds to both GR (107) and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (134). It is possible, then, that a putative membrane-associated form of GR could interact with group I metabotropic glutamate receptors, thus initiating the endocannabinoid-mediated inhibition of the HPA axis. Consistent with this hypothesis, preliminary data from our lab suggest that signalling through paraventricular group I metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits the HPA axis response to restraint in a manner similar to dexamethasone (Evanson and Herman, unpublished results). Figure 4 illustrates our model for how this signalling pathway might work.

Figure 4.

Model of a putative role for Homer-2 in mediating fast feedback through endocannabinoid signalling. Glucocorticoids bind to a membrane-associated form of GR (A), which is associated with group I metabotropic glutamate receptor, via Homer-2 binding (B). Glucocorticoid binding leads to activation of the Gq subunit of the glutamate receptor complex (C), which activates endocannabinoid synthesis, likely through interactions with phospholipase C (D). Endocannabinoids synthesised by phospholipase C are released and diffuse in a retrograde direction across the synapse and decrease glutamate release, as illustrated in figure 3.

Another signalling pathway of interest for neuroendocrinology involves the protein Annexin 1. Annexin 1 (formerly known as lipocortin 1 or lipomodulin) is a Ca2+ and phospholipid binding protein in the annexin family. It was first described in mouse macrophages as a glucocorticoid-induced protein, and mediates many of the anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids in these cells (135). Annexin 1 is expressed in the folliculostellate cells of the anterior pituitary (136), where it modulates nongenomic negative feedback regulation of ACTH secretion. Glucocorticoid exposure causes transcription independent translocation of annexin 1 to the plasma membrane (137). From there it appears to act in a juxtacrine manner, binding to putative receptors on pituicytes (138–140). Signalling through annexin 1 appears to mediate the rapid inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids on ACTH secretion in vitro (137). This signalling system can be reconstituted in a co-culture of folliculostellate cells and corticotrophs, but not in single culture of either one (141). These data are interesting in light of the fact that annexin 1 is expressed in the hypothalamus (142), mainly in glial cells (143), as well as in ependymal cells and tanycytes (144). These expression data suggest the possibility of an annexin-1 mediated signalling pathway in the hypothalamus, similar to that found in the pituitary gland. This possibility is supported by a study showing that annexin 1 inhibits cytokine-induced release of CRH from the hypothalamus in vitro and corticosterone secretion in vitro (145). Nongenomic glucocorticoid signalling involving annexin 1 has also been described in A549 lung fibroblasts (146), suggesting that annexin 1 may be a player in nongenomic glucocorticoid signalling in tissues outside of the HPA axis as well.

A note regarding nongenomic effects of adrenal steroids

A discussion of non-genomic actions of adrenal steroids brings up several questions. One is how a particular effect is classified as nongenomic. In this review, we have used the criteria set forth by Makara and Haller in evaluating evidence. These criteria include 1) rapidity of onset, 2) independence of the genome, and 3) independence from classical nuclear steroid receptors (116). The rationale for using these criteria are as follows: 1) A certain amount of time is needed for genomic signaling to occur; thus, effects occurring faster than this must be independent of genomic signaling. 2) If the effects persist either in the presence of inhibitors of translation or transcription, or occur in a system lacking genomic machinery (e.g. synaptosomes, which contain no nuclear material), they must be occurring independent of genomic signaling. 3) MR and GR are nuclear receptors, and generally act through altering gene expression. Effects that occur independently of these receptors are more likely to be independent of gene expression.

Although these criteria aid in classifying effects as nongenomic, they are not perfect. For example, the rapidity criterion would need to be very strict to rule out all known genomic events, as increased gene transcription has been described within as little as 7.5 minutes (147). Thus, there is a period of time over which nongenomic and genomic effects are likely to overlap. Second, although persistence of effects in the presence of genome inhibitors seems to be a strong support for the idea of nongenomic effects, these inhibitors will not affect signalling pathways that lead to gene repression. Also, gene expression may occur even in systems considered to be genome free (for example, local translation in dendrites, which would be a component of synaptosomes (148)). Third, there is now a relatively large literature suggesting that some nongenomic effects are mediated by these receptors, as discussed above. Thus, although these criteria can aid in classifying effects, they do not represent a perfect test. In this review, we have noted these criteria as much as possible. We also have considered the time criterion to be one of the most important, because the time course of the effects discussed above is known much more often than whether the effects meet the other criteria. We also feel that rapid effects, especially those occurring within 15 minutes or less, are more likely to be nongenomic than genomically-mediated.

Although glucocorticoid-induced transcriptional changes have been detected within as little as 7.5 minutes (147), this report was of a change in transcription only, and was done in a viral system. Further, 7.5 minutes was the earliest time that a change was detectable, while the maximal response was not evident until more than an hour after treatment. The fastest time frame in which genomic effects have been observed in non-viral systems using glucocorticoids is about 15–30 minutes, depending on cell type (116). Again, this time frame is from onset of glucocorticoid treatment until the effects are detectable, rather than maximal. In the case of fast feedback inhibition of the HPA axis by glucocorticoids, in contrast, the inhibition is maximal by 15 minutes after treatment (Evanson and Herman, unpublished data). Thus, although using the time criterion to classify results as presumably nongenomic leaves much to be desired, it remains one of the best criteria currently available.

A second concern when interpreting studies purporting to describe nongenomic effects of adrenal steroids regards the concentration of ligand necessary to achieve these effects, as well as the concentration of hormone available to tissues. In vivo adrenal steroid concentrations are affected by both the circulating hormone levels and also the degree of protein binding vs. free steroid levels in the plasma. In rats, peak plasma corticosterone levels in response to stress are often reported to be in the range of 400 to 900 ng/ml (149–152). However, these steroids are bound extensively to albumin and corticosteroid binding globulin in the plasma. About 95% of plasma cortisol in humans is protein bound, (153), although the fraction of free corticosterone may be higher in other systems (154–156). From these numbers, it is reasonable to believe that free circulating glucocorticoid levels may be at least as high as 20 to 100 ng/ml (~60 to 300 nM; see Table 1) during physiological conditions, although few studies have assessed free glucocorticoid levels. It is interesting to note that studies in mice deficient in corticosteroid binding globulin have revealed elevated free corticosterone in concert with blunted corticosterone responses to stress (157, 158). These results are consistent with the free corticosterone fraction acting in a rapid manner to limit the HPA axis response to restraint, as discussed above.

Table 1.

Concentrations of adrenal steroids needed to achieve nongenomic effects. Studies using natural glucocorticoids to achieve nongenomic effects are outlined, showing the experimental system used, the effect measured, the time needed for development of the effect, the steroid used and concentration. Where known, sensitivity to inhibitors of translation and transcription are noted.

| Experimental system | Effect | Time course | Steroid | Concentration | Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| sparrow | increased hopping activity | < 15 min | corticosterone | 4 μg (peak plasma levels ~25 ng/ml) | 34 | |

| taricha granulosa | decreased neuronal activity | 3 to 30 min | corticosterone | 25 μg | 101 | |

| tilapia pituitary | inhibition of prolactin release | < 20 min to 4 h | cortisol | 200 nM | 4 h effect not blocked by cycloheximide; caused by cortisol:BSA | 121 |

| mouse synaptosome | tryptophan uptake | 5 min | corticosterone | 10 μM | no nuclei in prep | 67 |

| mouse hippocampal slice | increased fEPSP slope | 10 min | corticosterone | 100 nM | 64 | |

|

| ||||||

| rat | locomotor and stereotyped behavior | 7.5 min | corticosterone | 2.5 to 5 mg/kg | 36 | |

| rat | behavior in EPM | 2 to 22 min | corticosterone | 0.5 mg/kg | 37 | |

| rat | locomotor and startle behavior | 15 min | corticosterone | 5 mg/kg | blocked by L-NAME | 40 |

| rat | Impaired memory retrieval in water maze | 30 min | corticosterone | 1 mg/kg | not blocked by anisomycin | 42 |

| rat | increased excitatory amino acid levels | 10 to 30 min | corticosterone | 2.5 to 5 mg/kg, i.p. | amino acids measured by microdialysis | 65 |

| rat | binding to brain membranes | corticosterone | 100 nM to 1 μM | 80 | ||

|

| ||||||

| anesthetized rat | decreased CRH-induced ACTH release | 15 to 30 min | corticosterone | 0.8 mg/kg IV | not blocked by actinomycin D | 49 |

| anesthetized rat | altered neuron firing rates | < 10 sec | cortisol | 4 to 6 nA, iontophoresis | 62 | |

| rat hypothalamic slice | inhibition of AVP release | 20 min | corticosterone:BSA | 100 nM to 100 μM | effect enhanced by neomycin 1 to 10 mM | 98 |

| rat hypothalamic slice | decreased EPSC input to parvocellular neurons | 3 to 5 min | corticosterone | 1 μM | effect also seen with dexamethasone:BSA | 53 |

| rat pituitary explant | decreased CRH-induced ACTH release | <10 min | cortisol | 10 to 100 nM | 45 | |

| rat hypothalamus explant | decreased acetylcholine-induced CRH release | <10 min | corticosterone | 1 pg/ml to 1 μg/ml | 48 | |

|

| ||||||

| rat pituitary primary culture | decreased CRH-induced ACTH release | 40 min | corticosterone | 1 μM | not blocked by cycloheximide | 46 |

| rat hypothalamic synaptosomes | decreased ACTH release | 35 min | corticosterone | 750 nM | no nuclei in prep | 51 |

| rat synaptosomes | glutamate uptake | 4 min | corticosterone | 1 μM | no nuclei in prep | 66 |

| rat erythrocyte ghosts | Hill coefficient of membrane bound acetylcholinesterase | cortisol | 1 μM | Indirect measure of membrane fluidity | 72 | |

| rat B103 neuroblastoma cells | inhibition of 5-HT-induced Ca++ influx | 5 min | corticosterone | 10 nM to 100 μM | effect also seen with corticosterone:BSA | 96 |

Although there can be argument whether levels used in various studies are physiologically relevant, it is clear that they are physiological in at least some cases. For example, some fast feedback studies have used only endogenous glucocorticoids to inhibit a subsequent stress response (e.g., (159)). In addition, studies using physiological glucocorticoid pulsatility lend support to the fast feedback inhibition paradigm (160). In these studies, it was found that glucocorticoids are secreted in ultradian pulses, approximately 1 hour long. Subjecting animals to stress during the falling phase of the glucocorticoid pulse reveals a blunted response to noise stress. In addition, peak brain corticosterone levels in rats subjected to swim stress are delayed by approximately 20 minutes, compared to plasma levels (161). Together, these results suggest the possibility that this non-responsiveness during the falling phase of a corticosterone pulse could be caused by fast feedback signaling by rising brain corticosteroid levels. Further studies will be necessary to determine whether this is a nongenomic effect.

In sum, many published studies have used adrenal steroid doses that likely represent pharmacological, rather than physiological doses. These studies and the effects described in them, although not necessarily physiological, are still important, given the widespread clinical use of adrenal steroids, especially glucocorticoids. However, there are also many studies whose effects are found in the physiological range. Thus, the nongenomic signaling pathways for adrenal steroids, in addition to their pharmacological utility, are also important for understanding the breadth of action of endogenous adrenal steroid hormone actions.

Conclusion

Adrenocorticosteroids have rapid effects at the subcellular, cellular, neural system, and behavioural levels. A number of these effects are mediated by nongenomic actions of these hormones, and they are clearly an important part of neural system function, including the regulation of their own secretion. The sheer number of effects on various levels that have been documented suggests that these effects are not merely side effects or artifacts of an experimental system, but that they are integral parts of the signalling cascades set in motion by the specific threat of electrolyte imbalance and the more generalised types of threats that are tackled by HPA axis activation.

The existence of these nongenomic actions of steroids suggests that drugs with specificity for nongenomic or genomic actions could be exploited, especially because there are many conditions and diseases in which adrenal steroids appear to play a part. HPA axis dysfunction is a common finding in major depressive disorders (162), and successful treatment of patients with this subtype of depression leads to normalization of the axis. HPA axis dysfunction has also been associated with other neural disorders, including fibromyalgia (163), chronic fatigue syndrome (163) and other pain syndromes (164, 165), and Alzheimer’s Disease (166). Further study is needed to determine the exact role of steroid hormones in these disorders, and whether nongenomic actions are important in the pathophysiology of these disorders.

Also importantly, synthetic glucocorticoids already in clinical use vary in their ability to activate genomic vs. nongenomic effects (167). These differences could be directly exploited by tailoring the choice of steroid to the pathways (genomic or nongenomic) that are primarily at work in the pathology of a condition. Alternatively, these differences in nongenomic action may need to be considered for reducing or changing the side-effect profile of drugs used primarily for their genomic activity. These differences among drugs already in clinical use further suggest that better pharmacological specificity can yet be attained, and highlight the importance of examining both genomic and nongenomic effects of candidate steroids during the drug development process.

In conclusion, the study of nongenomic effects of adrenal steroids has been a fascinating field to date. Further study of nongenomic steroid effects has the potential not only for a richer understanding of the activity and regulation of neural systems such as the HPA axis, but also for clinically useful treatments for disorders in the nervous system. Future study should focus on identifying and characterizing the receptors responsible for these nongenomic effects. The field also merits more investigation into the pharmacology and signalling pathways underlying the nongenomic effects of adrenal steroid hormones. The research leading to better understanding of these presents a rich and important area for continuing inquiry.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

This work was supported by NIH grants MH069725 (JPH), NS007453 (NKE), DK79710 (EGK), HL096830 (EGK), DK048061 (RRS), and DK066596 (RRS).

References

- 1.Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganong WF, Mulrow PJ. Rate of change in sodium and potassium excretion after injection of aldosterone into the aorta and renal artery of the dog. Am J Physiol. 1958;195:337–342. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1958.195.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein K, Henk W. Clinical experimental studies on the influence of aldosterone on hemodynamics and blod coagulation. Z Kreislaufforsch. 1963;52:40–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spach C, Streeten DH. Retardation Of Sodium Exchange In Dog Erythrocytes By Physiological Concentrations Of Aldosterone, In Vitro. J Clin Invest. 1964;43:217–227. doi: 10.1172/JCI104906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moura AM, Worcel M. Direct action of aldosterone on transmembrane 22Na efflux from arterial smooth muscle. Rapid and delayed effects. Hypertension. 1984;6:425–430. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.6.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wehling M, Kasmayr J, Theisen K. Rapid effects of mineralocorticoids on sodium-proton exchanger: genomic or nongenomic pathway? Am J Physiol. 1991;260:E719–726. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.5.E719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberman AC, Druker J, Perone MJ, Arzt E. Glucocorticoids in the regulation of transcription factors that control cytokine synthesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttgereit F, Scheffold A. Rapid glucocorticoid effects on immune cells. Steroids. 2002;67:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowenberg M, Tuynman J, Bilderbeek J, Gaber T, Buttgereit F, van Deventer S, Peppelenbosch M, Hommes D. Rapid immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids mediated through Lck and Fyn. Blood. 2005;106:1703–1710. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buttgereit F, Wehling M, Burmester GR. A new hypothesis of modular glucocorticoid actions: steroid treatment of rheumatic diseases revisited. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:761–767. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<761::AID-ART2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koukouritaki SB, Theodoropoulos PA, Margioris AN, Gravanis A, Stournaras C. Dexamethasone alters rapidly actin polymerization dynamics in human endometrial cells: evidence for nongenomic actions involving cAMP turnover. J Cell Biochem. 1996;62:251–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(199608)62:2%3C251::AID-JCB13%3E3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbach V, Walsh DE, Mainprice B, Bousquet J, Harvey BJ. Rapid non-genomic inhibition of ATP-induced Cl− secretion by dexamethasone in human bronchial epithelium. J Physiol. 2002;545:869–878. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.028183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verriere VA, Hynes D, Faherty S, Devaney J, Bousquet J, Harvey BJ, Urbach V. Rapid effects of dexamethasone on intracellular pH and Na+/H+ exchanger activity in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35807–35814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daufeldt S, Lanz R, Allera A. Membrane-initiated steroid signaling (MISS): genomic steroid action starts at the plasma membrane. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;85:9–23. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D, Zhang H, Lang F, Yun CC. Acute activation of NHE3 by dexamethasone correlates with activation of SGK1 and requires a functional glucocorticoid receptor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C396–404. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00345.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fluharty SJ, Sakai RR. Behavioral and cellular analysis of adrenal steroid and angiotensin interactions mediating salt appetite. Prog Psychobiol Physiol Psychol. 1995;16:177–212. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai RR, McEwen BS, Fluharty SJ, Ma LY. The amygdala: site of genomic and nongenomic arousal of aldosterone-induced sodium intake. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1337–1345. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein AN. Mineralocorticoids and cerebral angiotensin may act together to produce sodium appetite. Peptides. 1982;3:493–494. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(82)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fluharty SJ, Epstein AN. Sodium appetite elicited by intracerebroventricular infusion of angiotensin II in the rat: II. Synergistic interaction with systemic mineralocorticoids. Behav Neurosci. 1983;97:746–758. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.97.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson KM, Sumners C, Hathaway S, Fregly MJ. Mineralocorticoids modulate central angiotensin II receptors in rats. Brain Res. 1986;382:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Nicola AF, Seltzer A, Tsutsumi K, Saavedra JM. Effects of deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) and aldosterone on Sar1-angiotensin II binding and angiotensin-converting enzyme binding sites in brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1993;13:529–539. doi: 10.1007/BF00711461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutkind JS, Kurihara M, Saavedra JM. Increased angiotensin II receptors in brain nuclei of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H646–650. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.3.H646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniels D, Yee DK, Faulconbridge LF, Fluharty SJ. Divergent behavioral roles of angiotensin receptor intracellular signaling cascades. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5552–5560. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gekle M, Freudinger R, Mildenberger S, Schenk K, Marschitz I, Schramek H. Rapid activation of Na+/H+-exchange in MDCK cells by aldosterone involves MAP-kinase ERK1/2. Pflugers Arch. 2001;441:781–786. doi: 10.1007/s004240000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mihailidou AS, Buhagiar KA, Rasmussen HH. Na+ influx and Na(+)-K+ pump activation during short-term exposure of cardiac myocytes to aldosterone. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C175–181. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.1.C175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christ M, Meyer C, Sippel K, Wehling M. Rapid aldosterone signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells: involvement of phospholipase C, diacylglycerol and protein kinase C alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:123–129. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doolan CM, Harvey BJ. Modulation of cytosolic protein kinase C and calcium ion activity by steroid hormones in rat distal colon. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8763–8767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dantzler WH. Renal organic anion transport: a comparative and cellular perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1566:169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihailidou AS, Mardini M, Funder JW. Rapid, nongenomic effects of aldosterone in the heart mediated by epsilon protein kinase C. Endocrinology. 2004;145:773–780. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karst H, Berger S, Turiault M, Tronche F, Schutz G, Joels M. Mineralocorticoid receptors are indispensable for nongenomic modulation of hippocampal glutamate transmission by corticosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19204–19207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507572102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olijslagers JE, de Kloet ER, Elgersma Y, van Woerden GM, Joels M, Karst H. Rapid changes in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cell function via pre- as well as postsynaptic membrane mineralocorticoid receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2542–2550. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orchinik M, Murray TF, Moore FL. A corticosteroid receptor in neuronal membranes. Science. 1991;252:1848–1851. doi: 10.1126/science.2063198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Remage-Healey L, Bass AH. Rapid, hierarchical modulation of vocal patterning by steroid hormones. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5892–5900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1220-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breuner CW, Greenberg AL, Wingfield JC. Noninvasive corticosterone treatment rapidly increases activity in Gambel’s white-crowned sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii) Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1998;111:386–394. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landys MM, Piersma T, Ramenofsky M, Wingfield JC. Role of the low-affinity glucocorticoid receptor in the regulation of behavior and energy metabolism in the migratory red knot Calidris canutus islandica. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2004;77:658–668. doi: 10.1086/420942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandi C, Venero C, Guaza C. Novelty-related rapid locomotor effects of corticosterone in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:794–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mikics E, Barsy B, Barsvari B, Haller J. Behavioral specificity of non-genomic glucocorticoid effects in rats: effects on risk assessment in the elevated plus-maze and the open-field. Horm Behav. 2005;48:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kruk MR, Halasz J, Meelis W, Haller J. Fast positive feedback between the adrenocortical stress response and a brain mechanism involved in aggressive behavior. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:1062–1070. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.5.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikics E, Kruk MR, Haller J. Genomic and non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids on aggressive behavior in male rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:618–635. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandi C, Venero C, Guaza C. Nitric oxide synthesis inhibitors prevent rapid behavioral effects of corticosterone in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;63:446–453. doi: 10.1159/000127070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, Lim G, Zeng Q, Sung B, Yang L, Mao J. Central glucocorticoid receptors modulate the expression and function of spinal NMDA receptors after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25:488–495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4127-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sajadi AA, Samaei SA, Rashidy-Pour A. Intra-hippocampal microinjections of anisomycin did not block glucocorticoid-induced impairment of memory retrieval in rats: an evidence for non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids. Behav Brain Res. 2006;173:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tasker JG. Rapid glucocorticoid actions in the hypothalamus as a mechanism of homeostatic integration. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(Suppl 5):259S–265S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayers G, Sayers MA. Regulation of pituitary adrenocorticotrophic activity during the response of the rat to acute stress. Endocrinology. 1947;40:265–273. doi: 10.1210/endo-40-4-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Widmaier EP, Dallman MF. The effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on adrenocorticotropin secretion from perifused pituitaries in vitro: rapid inhibition by glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 1984;115:2368–2374. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-6-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abou-Samra AB, Catt KJ, Aguilera G. Biphasic inhibition of adrenocorticotropin release by corticosterone in cultured anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 1986;119:972–977. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-3-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dallman MF, Jones MT, Vernikos-Danellis J, Ganong WF. Corticosteroid feedback control of ACTH secretion: rapid effects of bilateral adrenalectomy on plasma ACTH in the rat. Endocrinology. 1972;91:961–968. doi: 10.1210/endo-91-4-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones MT, Hillhouse EW, Burden JL. Dynamics and mechanics of corticosteroid feedback at the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary gland. J Endocrinol. 1977;73:405–417. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0730405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hinz B, Hirschelmann R. Rapid non-genomic feedback effects of glucocorticoids on CRF-induced ACTH secretion in rats. Pharm Res. 2000;17:1273–1277. doi: 10.1023/a:1026499604848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones MT, Hillhouse EW. Structure-activity relationship and the mode of action of corticosteroid feedback on the secretion of corticotrophin-releasing factor (corticoliberin) J Steroid Biochem. 1976;7:1189–1202. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(76)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edwardson JA, Bennett GW. Modulation of corticotrophin-releasing factor release from hypothalamic synaptosomes. Nature. 1974;251:425–427. doi: 10.1038/251425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sato T, Sato M, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Corticosterone-induced changes in hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) content after stress. Endocrinology. 1975;97:265–274. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-2-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Halmos KC, Tasker JG. Nongenomic glucocorticoid inhibition via endocannabinoid release in the hypothalamus: a fast feedback mechanism. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4850–4857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04850.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feldman S, Weidenfeld J. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists in the hippocampus modify the negative feedback following neural stimuli. Brain Res. 1999;821:33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mizoguchi K, Ishige A, Aburada M, Tabira T. Chronic stress attenuates glucocorticoid negative feedback: involvement of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2003;119:887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akana SF, Chu A, Soriano L, Dallman MF. Corticosterone exerts site-specific and state-dependent effects in prefrontal cortex and amygdala on regulation of adrenocorticotropic hormone, insulin and fat depots. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:625–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaferi A, Bhatnagar S. Corticosterone can act at the posterior paraventricular thalamus to inhibit hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in animals that habituate to repeated stress. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4917–4930. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kovacs KJ, Makara GB. Corticosterone and dexamethasone act at different brain sites to inhibit adrenalectomy-induced adrenocorticotropin hypersecretion. Brain Res. 1988;474:205–210. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cook CJ. Glucocorticoid feedback increases the sensitivity of the limbic system to stress. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:455–464. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruf K, Steiner FA. Steroid-sensitive single neurons in rat hypothalamus and midbrain: identification by microelectrophoresis. Science. 1967;156:667–669. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3775.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dafny N, Phillips MI, Taylor AN, Gilman S. Dose effects of cortisol on single unit activity in hypothalamus, reticular formation and hippocampus of freely behaving rats correlated with plasma steroid levels. Brain Res. 1973;59:257–272. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mandelbrod I, Feldman S, Werman R. Inhibition of firing is the primary effect of microelectrophoresis of cortisol to units in the rat tuberal hypothalamus. Brain Res. 1974;80:303–315. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90693-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pfaff DW, Silva MT, Weiss JM. Telemetered recording of hormone effects on hippocampal neurons. Science. 1971;172:394–395. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3981.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiegert O, Joels M, Krugers H. Timing is essential for rapid effects of corticosterone on synaptic potentiation in the mouse hippocampus. Learn Mem. 2006;13:110–113. doi: 10.1101/lm.87706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Venero C, Borrell J. Rapid glucocorticoid effects on excitatory amino acid levels in the hippocampus: a microdialysis study in freely moving rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2465–2473. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu BG, Zhu DH, Chen YZ. Rapid enhancement of high affinity glutamate uptake by glucocorticoids in rat cerebral cortex synaptosomes and human neuroblastoma clone SK-N-SH: possible involvement of G-protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:261–265. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Neckers L, Sze PY. Regulation of 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism in mouse brain by adrenal glucocorticoids. Brain Res. 1975;93:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alzamora R, Michea L, Marusic ET. Role of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in nongenomic aldosterone effects in human arteries. Hypertension. 2000;35:1099–1104. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.5.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rossol-Haseroth K, Zhou Q, Braun S, Boldyreff B, Falkenstein E, Wehling M, Losel RM. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists do not block rapid ERK activation by aldosterone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shivaji S, Jagannadham MV. Steroid-induced perturbations of membranes and its relevance to sperm acrosome reaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1108:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whiting KP, Restall CJ, Brain PF. Steroid hormone-induced effects on membrane fluidity and their potential roles in non-genomic mechanisms. Life Sci. 2000;67:743–757. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Massa EM, Morero RD, Bloj B, Farias RN. Hormone action and membrane fluidity: effect of insulin and cortisol on the Hill coefficients of rat erythrocyte membrane-bound acetylcholinesterase and (Na+ + K+)-ATPase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;66:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(75)80302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stallkamp I, Dowhan W, Altendorf K, Jung K. Negatively charged phospholipids influence the activity of the sensor kinase KdpD of Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 1999;172:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s002030050783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lipworth BJ. Therapeutic implications of non-genomic glucocorticoid activity. Lancet. 2000;356:87–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gavrilova-Jordan LP, Price TM. Actions of steroids in mitochondria. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:154–164. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Buckingham JC. Glucocorticoids: exemplars of multi-tasking. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S258–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wong CW, McNally C, Nickbarg E, Komm BS, Cheskis BJ. Estrogen receptor-interacting protein that modulates its nongenomic activity-crosstalk with Src/Erk phosphorylation cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14783–14788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192569699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]