There are approximately 3.4 million infants and children in the world living with HIV, of which 91% are in Africa. Another 1.4 million African infants are born exposed to HIV every year (World Health Organization, 2013). Most are living in countries with severe shortages of all types of health-care workers. Previously, the management of paediatric HIV was considered the domain only of the medical doctor, and it was only they who were considered qualified to prescribe life-saving antiretroviral treatment (ART).

However, those days are now falling behind us. The extremely limited number of doctors in many parts of Africa means many patients, both children and adults, may not receive the medication they need for survival. Some countries adapted by permitting nurses and midwives with appropriate training to prescribe ART refills (Médecins Sans Frontières, 2012). Now, a number of ministries of health have taken the next important step in task-sharing—to permit nursing staff to initiate ART as well, thus breaking down a significant barrier in access for the millions of HIV-infected individuals living in districts where a doctor may be nearly impossible to find.

Children’s unique needs

This change may be especially relevant for children. Nurses and midwives have always been the frontline of paediatric health care, and are engaged in the continuum of care before infants are even born. They are essential in monitoring antenatal development, providing safe and healthy deliveries, identifying neonatal complications, and administering critical immunisations. Maternal and Child Health (MCH) clinics are typically staffed by nurses and midwives, and a doctor may or may not be available for consultation. This setting is often where nurses and midwives are making the first impact on children affected by HIV.

Counselling and testing pregnant women, providing those who are HIV-positive with medications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT), and dispensing preventive medications to exposed infants help greatly reduce the numbers of children born with HIV, with potential to decrease mother-to-infant transmission from more than 50% to less than 2%. For those children who do become infected, early diagnosis is crucial. For older children accessing medical care who have not been diagnosed previously, vigilance in testing is also necessary. Again, all of these processes are taking place at MCH sites across Africa, under the watchful eyes of midwives and nurses who refuse to let the needs of these children slip through the system.

When early diagnosis is followed by early initiation of treatment, mortality for these children is reduced by a remarkable 76% (Violari et al, 2008). This linkage, however, between diagnosis and treatment is often a challenging one where many children are lost to follow-up or initiation of ART is extensively delayed. A referral to a specialised health centre, often a long distance away, creates barriers that can stall or terminate the entire cascade of services for the child. Sometimes, the wait for a doctor can cost a child their life.

New skill sets

These facts underscore the urgency of training and experience that provide nursing and midwifery professionals with the confidence and skills they need to provide HIV services of all levels for children, including initiation of ART. Some nurses are comfortable providing these services for adults, but feel intimidated by the particulars of paediatric HIV. Testing protocols, clinical patterns, drug options, and weight-adjusted dosing are all domains where specific paediatric knowledge is necessary.

However, all of these can be answered through on-site or off-site paediatric HIV training and provision of simple job aids. Of particular use can be a pocket reference that consolidates all of the weight-based dosing information and other important tables, checklists and algorithms in one place. With skills and tools such as these, nurses and midwives are well-suited to provide paediatric HIV treatment competently and confidently to children who are out of reach of doctors. Recent research, including a large study out of South Africa, demonstrates that nurse prescribers can provide adult ART at equal or even higher levels of quality than doctor-only prescribing (Fairall et al, 2012). Similar research in paediatric HIV is needed to confirm that this model of service delivery is safe and prudent, allowing children the same opportunities to access ART from nurses.

‘When early diagnosis is followed by early initiation of treatment, mortality for [HIV-infected] children is reduced by a remarkable 76%’

There are countless professionals around the world tackling the enormous challenges posed by paediatric HIV: researchers, advocates, epidemiologists, technicians, paediatricians, social workers, policy-makers, fundraisers and various others committed to creating an AIDS-free generation. More and more, it is the African nurse or midwife who is actually implementing the solutions that currently exist—prevention, diagnosis, treatment, psychosocial support—and directly changing the fates of those affected children. Their success in this role is vital to us all.

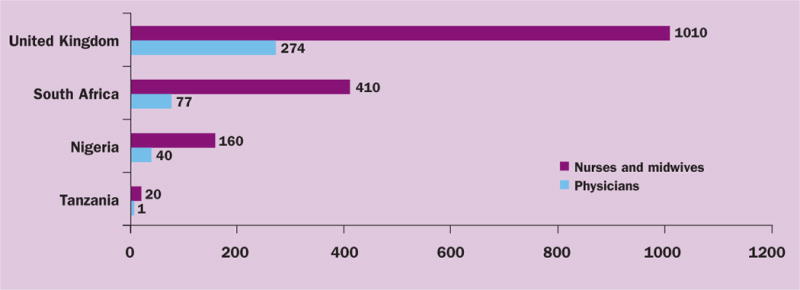

Figure 1.

Number of health workers, per 100 000 population (data from World Health Organization Global Health Observatory)

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This project has been supported by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Author contribution statement: Author participated in the development of manuscript concept, literature review, writing of draft, revision process, review of final manuscript, and approval of decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, Timmerman V, Uebel K, Zwarenstein M, Boulle A, Georgeu D, Colvin CJ, Lewin S, Faris G, Cornick R, Draper B, Tshabalala M, Kotze E, van Vuuren C, Steyn D, Chapman R, Bateman E. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): A pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):889–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Médecins Sans Frontières. Speed up scale-up: Strategies, tools and policies to get the best HIV treatment to more people, sooner. 2012 tinyurl.com/d55vrca (accessed 19 March 2013)

- Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, Babiker AG, Steyn J, Madhi SA, Jean-Philippe P, McIntyre JA. Early Antiretroviral Therapy and Mortality among HIV-Infected Infants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(21):2233–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory. 2013 www.who.int/gho (accessed 19 March 2013)