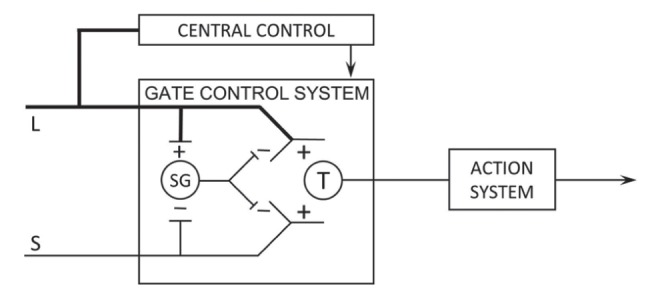

November 2015 marks the 50th anniversary of the 1965 Science publication “Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory” by Ronald Melzack and Patrick D Wall (1), in which the authors introduced the gate control theory of pain that has since revolutionized our understanding of pain mechanisms and management. The brilliance, creativity and critical thought that went into the formulation and explication of the gate control theory of pain can best be appreciated by reading the original article. Fifty years later, having become part of our scientific history and accepted as common knowledge, the essence of the theory is often conveyed by the familiar diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1).

A schematic illustration of the gate control theory of pain proposed by Melzack and Wall (1), demonstrating how the gating mechanism in the spinal dorsal horn modulates transmission of nerve impulses from afferent fibres to spinal cord transmission cells. The gating mechanism is affected by the relative activity in large- and small-diameter fibres, with the former inhibiting transmission (closing the gate) and the latter facilitating transmission (opening the gate). Notably, the spinal gating mechanism is also modulated by descending nerve impulses from the brain. The authors proposed that the spinal transmission cells activate an action system in the brain comprising regions that underlie the experience and behaviours characteristic of pain. Reproduced with permission from Melzack and Wall (1)

In 1982, the article was recognized as a Citation Classic in Eugene Garfield’s weekly publication Current Contents. Citation Classic commentaries were introduced by Garfield to provide the scientific community with “a kind of living history” illustrating the “human side of science” (2). The Citation Classic commentary by Melzack and Wall (3) was a one-page synopsis that included an abstract describing the gate control theory and the authors’ reflections on the article’s importance and popularity, its ongoing scientific relevance (17 years after publication) and the transformation in treatment it brought about. Because it is as relevant today as it was in 1982, we have reproduced it as Figure 2.

Figure 2).

“This Week’s Citation Classic” from the June 7, 1982 issue of Current Contents, featuring an abstract and commentary by Melzack and Wall (3) describing the culture of pain at the time, their thoughts on the initial resistance to the gate control theory, its ultimate acceptance and success, and how the theory changed the scientific and clinical communities’ conceptualization of pain from that of a symptom of a disease, to a major health problem in need of specialized treatment. Reproduced with permission from Melzack and Wall (3)

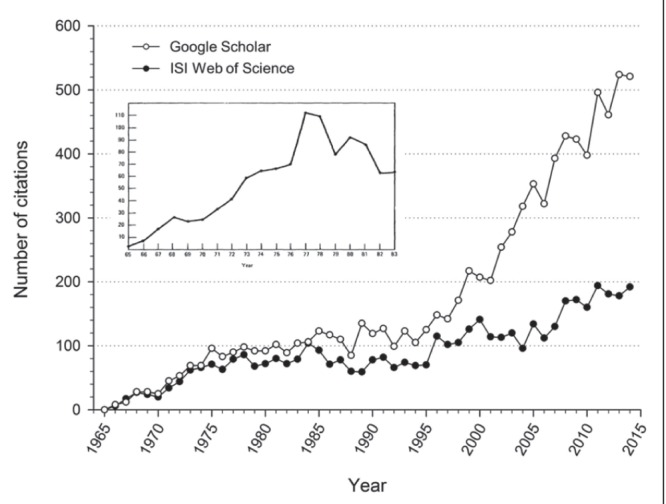

Two years later, Garfield (4) highlighted the publication’s unusual pattern of citations, noting “the resistance of the research community to new theories, particularly when they are at odds with established dogma”. He pointed out that it had taken 12 years from the time of publication, for the article to reach its peak number of yearly citations of 112 in 1977, for a total of 1027 citations in the 19-year period from 1965 to 1983. The initial resistance (3,4) was gradually overcome by acceptance, as an increasing body of scientific findings supported the concept of a spinal gating mechanism. Remarkably, as we approach the 50th anniversary of its publication, the article’s citation rate has continued to climb, reaching an all-time yearly high of 525 (in 2013, measured by Google Scholar [Google Inc, USA]) or 195 (in 2011, measured by the ISI Web of Science [Thomson Reuters, USA]) for a cumulative citation count as of 2014 of >8800 (Google Scholar) or >4500 (ISI Web of Science) (Figure 3).

Figure 3).

Annual citation count from 1965 to 2014, for the gate control theory paper by Melzack and Wall (1) based on data from the ISI Web of Science (Thomson Reuters, USA) and Google Scholar (Google Inc, USA) (as of September 18, 2015). The increasing trend in the yearly number of citations shown in the inset, and noted by Garfield in 1984 (4), has been maintained in the ensuing 30 years by both citation sources, but even more so by Google Scholar when, beginning in the mid-to-late 1990s, the citation rate increases dramatically – reminiscent of ‘windup’ (13) (see [14],Figure 2), but on a grand scale! Inset reproduced with permission from Garfield (4)

As noted by Melzack and Wall (3) (Figure 2), the acceptance and popularity of the theory was, in part, facilitated by the concept of a gate:

A fortunate aspect of our publication in 1965 is the use of the phrase ‘gate control.’ It evokes an image that is readily understood even by those who do not grasp the complex physiological mechanisms on which the theory is based.

Fifty years later, this aspect of the publication continues to ring true. In particular, the ‘gate’ metaphor serves as a convenient and useful way to explain to patients what pain is, and how and why it fluctuates from day to day. Many current chronic pain education and pain self-management programs refer to the gate control theory and, in particular, to the gating mechanism in the spinal cord. For example, in one of the more influential pain self-management books, LeFort et al (5) state:

Melzack and Wall said that there is a transmission station in the spinal cord that influences the flow of nerve impulses to the brain. They called this transmission station a ‘gate’. Think of it just like a gate you can open or close to get to your backyard. ... The gate can be opened or closed in a number of ways, including by the brain itself. ... The brain can send electrical messages down nerve pathways to close the gate and shut out or reduce the flow of nerve impulses to the brain, or send messages that do just the opposite. Many factors can open or close the gate. ... For example, positive mood, distraction, and deep relaxed breathing can act to close or partially close the gate while strong emotions like fear, anxiety, and expecting the worst can open the gate.

Moreover, Melzack and Wall’s comment (Figure 2) about the article’s relevance to a multidisciplinary base continues to be true. Citations to the article can be found in almost every field, including subdisciplines within science and technology, medicine, veterinary science, the social sciences, and the arts and humanities.

The gate control theory has had a major clinical impact on how pain is viewed by health care practitioners, how patients are treated, and, perhaps more importantly, it has provided patients with hope that pain relief is possible (6). The modulation of afferent input by the spinal gating mechanism and the dynamic role of the brain in processing pain-related information provided a physiological basis for previously inexplicable, ‘bizarre’ symptoms (eg, phantom limb pain) believed to arise from psychopathology (7). Moreover, anxiety, depression, worry and other psychological factors, which had been considered ‘reactions to pain’ came to be viewed as integral to the processing of pain-related information (6). The theory also had a profound influence on other approaches to managing pain, including a reduction in irreversible, ablative surgical procedures, and it heralded new therapies, such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and other forms of neuromodulation, such as peripheral nerve, spinal cord and deep-brain stimulation.

Fifty years after its publication, the gate control theory has stood the test of time (8); the conceptual components of the gate control theory are as relevant now as they were in 1965 (8,9), and countless patients have benefitted from the clinical innovations spawned by the theory. The historical prominence of Canada’s pain research community (10) can be traced to pivotal developments in the field, most notable among them, the gate control theory of pain. Pain Research and Management, the official journal of the Canadian Pain Society, is proud to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Melzack and Wall’s gate control theory with the international community of pain researchers and clinicians, who work toward the common goal of abolishing the “silent epidemic” (11) of “needless pain” (12).

REFERENCES

- 1.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–9. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garfield E. Introducing Citation Classics: The human side of scientific reports. Current Contents. 1977;1:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melzack R, Wall PD. Citation Classic – Pain Mechanisms: A new theory. Current Contents. 1982;22 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garfield E. The articles most cited in 1961–1982. 5. Another 100 Citation Classics and a summary of the 500 papers identified to date. Current Contents. 1984;42:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeFort S, Webster L, Lorig K, et al. Living a healthy life with chronic pain. Boulder: Bull Publishing Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melzack R, Katz J. Pain. WIREs Cogn Sci. 2013;4:1–15. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagliese L, Katz J. Medically unexplained pain is not caused by psychopathology. Pain Res Manag. 2000;5:251–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickenson AH. Gate control theory of pain stands the test of time. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:755–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.6.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendell LM. Constructing and deconstructing the gate theory of pain. Pain. 2014;155:210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merskey H. History of pain research and management in Canada. Pain Res Manag. 1998;3:164–73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wall PD, Jones M. Defeating pain: The war against a silent epidemic. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melzack R. The tragedy of needless pain: A call for social action. In: Dubner R GG, Bond MR, editors. Proceedings of the Vth World Congress of Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendell LM. Physiological properties of unmyelinated fiber projection to the spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 1966;16:316–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(66)90068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolf CJ, Thompson SW. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991;44:293–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90100-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]