Abstract

Background

The relationship between hemophilia team interventions and achievement of optimal clinical outcomes remains to be elucidated. The British Columbia Hemophilia Adult Team has previously reported results of a comprehensive approach to individualize prophylaxis that has resulted in substantially reduced bleeding rates. In order to facilitate knowledge exchange and potential replication, it was important to gain a thorough understanding of the team’s approach.

Methods

A focus group of the British Columbia Hemophilia Adult Team was conducted to identify specific roles and processes that might be contributing to the prophylaxis regimen outcomes in this clinic. The focus group consisted of two workshops; one to describe the individual and collective roles of the clinic team in providing clinical care and guiding patients toward individualized prophylaxis; and the other to describe the patient journey from initial contact through reaching a successful engagement with the clinic.

Results

Analysis of the results revealed team roles and processes that underpinned a shared decision-making relationship with the patient with a particular focus on supporting the patient’s autonomy. Within this relationship, team focus shifts away from “adherence” toward the process whereby patients design and implement prophylaxis regimens resulting in reduction or elimination of bleeding episodes.

Limitations

Using the current methodology, it is not possible to demonstrate a causal link between specific team processes and improved bleeding rates in patients.

Conclusion

Through the active support of patient autonomy in all aspects of decisions related to hemophilia management, the British Columbia Hemophilia Adult Team approach de-emphasizes “adherence” as the primary goal, and focuses on a prophylaxis plan that is customized by the patient and aligned with his priorities. Adoption of this comprehensive team approach facilitates shared goals between the patient and the team that may optimize treatment adherence, but more importantly, reduce bleeding rates.

Keywords: individiualized prophylaxis, shared decision-making, autonomy support, comprehensive care team

Introduction

Hemophilia is an inherited bleeding disorder characterized by a deficiency in clotting factors and expressed predominantly in males.1 The prevalence is approximately 1 in 10,000 live births for hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) and 1 in 60,000 for hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency).2 Men with hemophilia experience bleeding into the major joints (ankles, knees, and elbows) or other areas due to trauma, medical procedures, or from seemingly unknown provocation. Bleeds may cause irreparable joint damage leading to chronic pain and disability with a major impact on functionality and quality of life.3,4

Self-administered intravenous infusions of clotting factor to prevent bleeds (prophylaxis) have been routinely utilized in Canada in the pediatric population with severe hemophilia (factor activity <1%) over the last 15–20 years. Prophylaxis is now also becoming the standard of care for adults with severe hemophilia and established joint damage.5,6 The literature describes many approaches to prescribing prophylaxis in adults, including the measurement of plasma clotting factor levels at specific timed intervals to tailor prophylaxis regimens to the individual.7 As a result of these efforts, bleeding rates are declining, and patients are leading more fulfilled and productive lives.8–11 However, intravenous infusions as often as every other day can be onerous for adults, especially for those who have few bleeding episodes and, historically, are comfortable with “on-demand” treatment (infuse clotting factor only when having a bleed). Consequently, not all adult patients with severe hemophilia have adopted a prophylaxis regimen, and some continue to needlessly suffer from the consequences of bleeding episodes that could have been prevented.

A prevailing belief of most hemophilia treaters is that patient adherence to prescribed treatment regimens is crucial to the reduction or elimination of bleeding episodes. Barriers to optimal adherence include lack of time, lack of patient engagement with clinic, minimal physical symptoms, financial burden, lack of knowledge, age (adolescents and older adults), forgetfulness, and lack of convenience.12–14 Higher adherence is associated with prophylaxis over on-demand regimens, nursing support, a positive relationship with the clinical team, longer time spent at clinic visits, and experience of symptoms.12–14 Thus, most factors negatively influencing adherence are linked directly to the patient, whereas several key factors leading to better adherence are generally linked to good clinical practice of hemophilia treatment providers. In developed countries, comprehensive hemophilia care provided by well-trained interdisciplinary teams promotes physical and psychosocial health, improves quality of life, and is associated with decreased morbidity and mortality.1,15 However, there is a paucity of literature focusing on frameworks for optimal support of prophylaxis through a more formalized shared decision-making process between the adult patient and the care team.

The British Columbia Hemophilia Adult Team (BCHAT) in Vancouver, Canada has reported preliminary clinic and patient outcomes resulting from a focused approach to share decision-making with patients in comprehensive hemophilia care. Training in motivational interviewing techniques provided the impetus to team adoption and commitment to this approach. Through live telephone support, patients were offered greater choice in clinic appointment times and appointment reminders. Positive outcomes included improved patient attendance at clinics as shown by a decrease in no-show rates from 17% to 5%, in spite of a threefold increase in number of clinic appointments.16 A pilot study utilizing intensive patient autonomy support during individualized dosing prophylaxis has reported substantially reduced bleeding rates. After 4 months of this approach, only nine cumulative bleeds were observed compared with a baseline of 25 bleeds (64% relative reduction) in a group of seven adults (P<0.05). The proportion of these subjects with zero bleeds was 57% on supported individualized prophylaxis, where clotting factor dose and/or frequency was specifically tailored to the patient, compared with 14% previously on standard prophylaxis (2–3 times weekly).17

In order to share lessons that the BCHAT has learned through their approach to shared decision-making during patient care, the preliminary step was to first clearly identify the process of treating an individual with hemophilia through individualized prophylaxis. The primary aim of this paper is to describe how BCHAT comprehensively partners with hemophilia patients to individualize prophylaxis.

Methods

A descriptive qualitative study was conducted in February 2015 using a focus group as the means of data collection. Participants were all members of the BCHAT, integral to the project, and consent to participate in the focus group and ethical approval was not required by the organization. The focus group question was: What is the process by which this team partners with the adult prophylaxis patient with hemophilia A or B, and how can it be presented in a manner that lends itself to replication?

Study process

Participants were all members of the BCHAT, integral to the project, and consent to participate in the focus group was not required by the organization. A 1-day in-person focus group was conducted of the BCHAT. A researcher/professional certified facilitator18 led the meeting using Technology of Participation (ToP®) methodology.19 The focus group comprised two separate consecutive workshops; one to describe the individual and collective roles of the clinic team in providing clinical care and, specifically, in working with patients toward individualized prophylaxis (Roles Workshop); and the other one to describe, from the clinician perspective, the patient journey from the time of initial contact with the clinic through reaching a successful engagement with the clinic (Process Workshop).

In the “Roles” workshop, each group member created a written list of his or her own roles within the team, which was then supplemented by suggestions from other team members. The individual roles were then combined as one master list and grouped in themes by the participants. Each theme was given a name in the form “verb-noun”. In the “Process” workshop, each group member contributed individual activities to a large conceptual timeline. In each of the two workshops, following additions, corrections, and clarifications, participants were asked to collectively indicate roles and activities that the group found easy to perform, difficult to perform, easily taught to others, and difficult to teach to others. Also common to each workshop, members were asked to vote on the roles and activities they considered to have the most impact on bleeding outcome in patients on prophylaxis. Votes were counted in real time to identify the top roles and clinic activities in terms of engaging the patient in the process of individualizing their prophylaxis regimens and resulting impact on bleeding episodes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Top roles or activities to engage the patient in the process of individualizing prophylaxis regimens and reduce bleeding episodes as rated by the BCHAT

| Role or activity | To do | To teach |

|---|---|---|

| Getting the patient to clinic and minimizing no-shows | Hard | Easy |

| Starting with the patient through gaining trust, avoiding paternalistic/prescriptive approach, and extracting patient perspective | Easy | Hard |

| Shared decision-making with the patient | Easy | Hard |

| Ask patient how they think they are doing and explore their motivation for change | Easy | Easy |

| Reviewing pattern of bleeds and looking for patient insight | Easy | Easy |

| Follow-up and follow-through to individualize prophylaxis regimen | Hard | Easy |

| Post-clinic team meeting to pool information, share insight and plan follow-up | Easy | Easy |

| Building better clinical care through inquiry, research participation, involvement of stakeholders | Easy | Easy |

Note: Some roles or activities were also rated in terms of ease of doing or teaching to other care providers.

Abbreviation: BCHAT, British Columbia Hemophilia Adult Team.

The focus group concluded by prioritizing the areas for improvement in the patient/clinician interaction.

Analysis

Focus group data were analyzed as part of the workshops, in accordance with the ToP method.20 Idea units (in this case, “roles” and “processes” generated from the workshop activities) were individually written on sheets of paper by the BCHAT, and the facilitator/researcher worked with the team to assemble the most closely associated idea units into groups. Once the team agreed that the ideas were appropriately grouped, the team labeled each group by core representative theme. These groups were formed into higher-order groups, thus again creating a hierarchical tree organized structure that showed further relationships between the data.

Results

The focus group was attended by eight out of nine members of the hemophilia care team, comprising two nurses, two physicians, one social worker, one physiotherapist, one secretary, and one clinical research assistant. Team members had worked in the program for >10 years (n=2, DG and SS), 5–10 years (n=3, KM, SJ, and CB), 1–4 years (n=1, MY), and <1 year (n=2, NS and LS).

The two major concepts (roles and process) were further stratified due to the emergence of themes during the workshops.

Roles

Four major themes emerged in the area of Roles: clinical tasks and responsibilities, aligning clinical decisions with patient needs, process flexibility, and commitment to growth.

Clinical tasks and responsibilities

Team members discussed roles associated with a standard set of clinical tasks and responsibilities, common to all clinics. These included basic clinical tasks, such as triaging and gathering information, performing consultation on a specific issue, providing a diagnosis and treatment recommendations, documentation, and follow-up, as well as logistical skills such as coordination, facilitation, organization, preparation, and accountability. Clinical outcome measurement was a role common to all members.

Aligning clinical decisions with patient needs

Team members identified the considerable group effort to center clinical decisions on the needs and priorities of the patient. This imperative started with the first point of contact: appointment-setting with the secretary during live telephone support. Mindful handling of this first interaction was deemed to be critical for ongoing rapport development. The practical goal of this initial interaction was to encourage patients to attend a clinic appointment and uncover any source of apprehension. Extracting and responding to the underlying motivation for the patient to visit with the team was deemed worthy of additional effort in order to better frame the upcoming visit. The team emphasized the importance of avoiding prescriptive or paternalistic behavior during this interaction.

On the clinic day, the first point of face-to-face contact was also deemed to be critical to set the tone for the upcoming interactions. In some cases, identifying areas where early success could be easily achieved that were congruent with best medical practice was identified as extremely helpful to gain patient trust and confidence. Concrete priorities identified by a patient that were less medically pertinent (eg, system navigation through insurance or disability/compensation issues) were sometimes given early attention by the group to facilitate building rapport, with the recognition that future interactions around medical issues would follow once this concrete priority had been acknowledged and/or addressed. The team engaged in purposeful listening to validate patient experiences, provide a non-judgmental “sounding board”, and begin a relationship of shared decision-making with the patient. This followed the framework of “autonomy support”, with the goal of determining and addressing the patients’ concrete priorities.

Process flexibility

Participants noted the importance of maintaining flexibility; both to respond to patients’ needs and to continuously seek improvement of clinical care. An overarching mandate was identified for remaining genuine and keeping the scope of the clinical tasks grounded in reality. Specific strategies included offering flexible appointment options, allowing multiple options for access to clinical team members (telephone, email, and remote health video link) and, after careful discussion, empowering patients to suggest and implement a change to the treatment plan. Additionally, the team cultural environment was open for considering all ideas to adapt and shift the clinic structure or function as well as for “pushing boundaries” within safety and reason.

In discussing the role of flexibility in achieving outcomes, the group observed that several years prior a restrictive clinic funding model with a focus on workload measures along with increasing workload but no additional funding created an environment where pressure to adapt was high. The team felt that in this context, flexibility was the only means for providing best clinical care.

Commitment to growth

The fourth theme identified in “Roles” centered on the team’s commitment to the professional growth of each member. The investment in additional training to build and develop skills was recognized as a means to retain an individual as part of the team and improve overall professional satisfaction. As with all teams, there are periods of stress with accompanying conflict. Working to resolution through these periods leads to continued team growth.

Process results

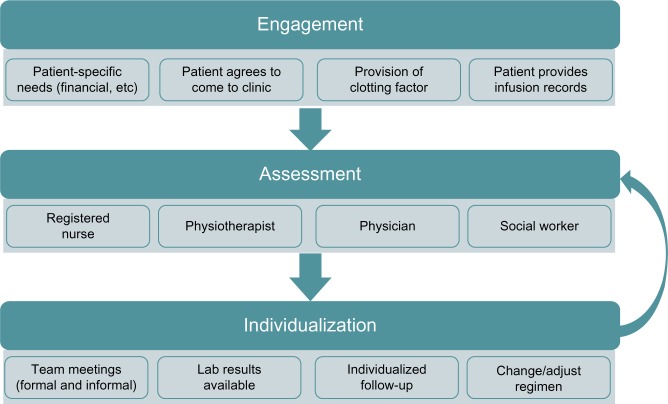

The team identified activities that take place as a patient experiences individualized prophylaxis that seamlessly interfaces with clinic services. The clinic’s partnership journey with the patient was divided into three phases: engagement, assessment, and individualization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The partnership journey with the patient.

Note: The team identified three phases in the partnership journey with the patient: engagement (preparation for first clinic visit), assessment (patient-driven process), and individualization (follow-up and decision-making).

Engagement

The goals of engagement were to get the patient to clinic, and to obtain accurate self-reported clotting factor infusion records. These records are necessary for evaluation of the patient’s efforts to prevent or treat bleeding episodes. A number of engagement strategies were employed, depending on the patient’s desire and ability to participate (eg, customizing appointment times to best meet patient needs, identifying resources to offset the burden of travel to clinic, tailoring the format for infusion record submission to patient preference and ability, and linking the provision of clotting factor for home use to the process of infusion record review). Once these goals were achieved, on going engagement required additional strategies to ensure that patients place value on continued collaboration with the team and clinic services. A pivotal strategy was the consistent and open use of patient infusion and bleeding records to inform the discussion around treatment and lifestyle decisions.

Assessment

Assessment can be further broken down into focus of discussion, conversation style, and emergence of a direction for change. Each team member drew outpatient insight on key areas such as factors that influence bleeding frequency, motivation to reduce bleeding events, and desire to increase capacity for activity and productivity. Assessment is an opportunity to identify factors that have the potential to further strengthen engagement with the clinic. For example, young men transitioning from the pediatric clinic quickly find the social worker to be a key conduit to vocational planning and educational funding. Additionally, point-of-care ultrasound offered by the physiotherapist often leads to patient-initiated visits to understand more about joint status or a recent bleed.

Conversations were approached through motivational interviewing techniques,21 which emphasize respect for patient autonomy. Team member roles were crafted as partner and coach, rather than expert and prescriber. Patients were offered the option of hearing more about treatment advances or participation in research. Rather than focusing on adherence and recrimination for “less-than-perfect” records, open discussion of the accuracy of self-report infusion data was encouraged. Patients were often invited to share their expertise with medical trainees, who benefit from hearing first hand about hemophilia self-management experiences.

As assessment progressed, impromptu team discussions occurred to share key patient priorities and the emergence of any direction for treatment change or adjustment. In situations where the desire for change emerged during the clinic visit, the group identified an immediate role for coaching the patient to the desired goal through his own motivation.

Individualization

The entire team assembled during weekly scheduled meetings to pool information and to ensure a follow-up plan, should it be recognized that the patient could benefit from an adjustment to the prophylaxis regimen. However, the idea of altering the existing plan must be generated by, or openly supported by, the patient at or after the clinic visit. Thus, the patient was fully integrated into this process in clinic and during follow-up conversations where laboratory results were collaboratively reviewed and interpreted. The patient was then encouraged to create an approach that emphasized his priorities and willingness to change. A follow-up plan was negotiated to allow the patient regular access to the team as he implements his chosen approach to prophylaxis. Graphic displays of infusion records and bleeding activity were provided so patients could reflect on their progress and collaborate with the team on any on going refinements. Follow-up encounters occurred in-person, by telephone, email, or video teleconferencing.

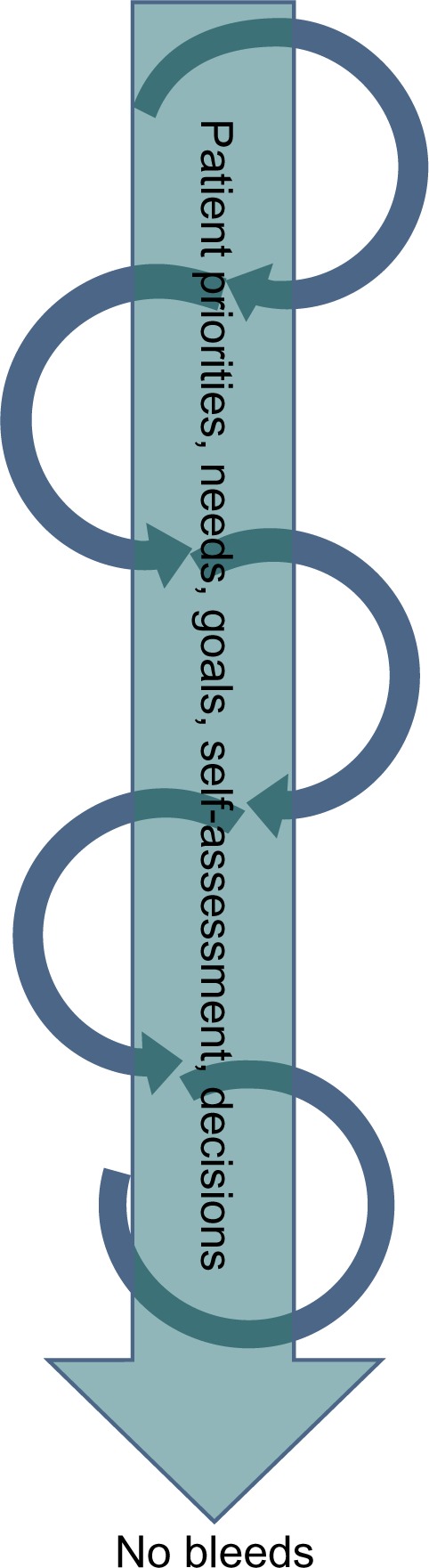

Although the phases of this process (engagement, assessment, and individualization) are superficially sequential, they are highly iterative. Decisions were made organically as the patient and team worked together to gain shared insight on opportunities to improve outcomes through optimization of prophylaxis. In practice, the team circled back within each phase and repeated activities, investigations, and conversations, as often as required until a decision was made. Patient priorities, needs, goals, and self-assessment dictated the clinical decision at each point (Figure 2). Thus, each clinical decision was, in reality, a patient choice. In other words, measurement of outcomes in this clinic setting actually tested the effectiveness of patient choice for determining clinical care and reducing bleeding rates.

Figure 2.

Patient priorities are central to shared decision-making.

Note: Shared decision-making is given shape and direction by a central pillar comprising patient priorities, needs, goals, self-assessment, and finally, decisions.

The team noted the importance of demonstrating respect of, and support for, patient decisions, feeling that challenging the patient’s readiness to change not only fails, but could also disturb the relationship. Instead, the team actively facilitated the next opportunity to build on any progress that has been made.

Whether prophylaxis patients were new to the clinic, transitioning from the pediatric clinic, or from the existing clinic population, these phases were evident, and all activities revolved around the central theme of prioritizing patient choices.

Translation and impact

In order to assess how easy it would be to translate and replicate these insights for other teams, within each workshop, the BCHAT identified the roles they considered the easiest and hardest to perform and to teach to other team members.

Inter personal skills, such as team building, knowledge sharing, and “starting with the patient”, were identified as the most straightforward roles to perform. Roles viewed as the hardest to perform related to managing process complexity, such as the need to be constantly flexible; effective documentation and follow-up; and the measurement of outcomes.

Easy-to-teach roles included performing the duties of, and constantly trying to improve delivery of standard clinical care. Specific activities cited were knowledge exchange/translation, listening purposefully, and tapping into concrete patient priorities (eg, writing a prescription or giving career advice). Integrating flexibility was labeled as a role that was both difficult to teach and perform. The adoption of co-piloting/coaching into daily clinical care was also difficult to teach to others. Moreover, the philosophy of celebrating diversity and creativeness of the team was viewed as difficult to teach in the setting of long-ingrained institutional and medical cultural behavior that emphasizes “top-down” leadership.

Finally, the identified roles/functions that had the greatest impact on positive clinical outcomes were those related to centering all clinical decisions on the needs and priorities of the patient and sharing decision-making. The team also agreed that working toward building better patient care delivery methods was a foundation for improving patient outcomes.

Areas for process improvement

During the focus group, clinic team members identified several aspects of the process that should be improved. Reliance on an informal flow of information during a busy clinic results in repetitious conversations for the patient (ie, speaking with the nurse, physician, social work, and physiotherapist) and may be inefficient. A formal and timely way to pass on what happened at each consult (both medical content and engagement process) rather than “in the corridor” is needed. Furthermore, the decision to change prophylaxis rarely happens during the clinic itself; more likely, it will be based on subsequent laboratory investigations or other information, with a final decision following within 2–3 weeks. The current informal follow-up process, combined with limited resources, has the potential to reduce momentum to the point where the prophylaxis plan is not optimal. In particular, re-booking the patient into the clinic to re establish momentum is challenging from a time perspective for both patients and the clinic. Thus, a research focus on shared decision-making that takes place outside the clinic day (ie, in the individualization phase) was perceived by the group as a key endeavor for improving patient outcomes. Finally, a documentation process to specifically capture the conceptual elements of the work is needed.

Discussion

In order to optimize their quality of life, individuals with hemophilia need to prevent joint bleeding. This is best achieved with prophylactic self-infusion of clotting factor concentrates. Although the concept of adherence to hemophilia prophylaxis regimens receives much focus in the literature, what remains unclear is the relationship between hemophilia comprehensive care team interventions and achievement of optimal clinical outcomes. The BCHAT has observed a reduction in bleeding rates with their approach to individualized dosing prophylaxis through the adjustment of clotting factor dose, infusion frequency, or both.17 A focus group of the BCHAT was convened to identify specific roles and processes that might be contributing to these outcomes. A major thread in the focus group analysis was the nature of the relationship developed with the patient. Described by the team as “co-piloting”, this relationship formed the foundation upon which patients design and implement a customized prophylaxis regimen leading to the elimination or reduction of bleeding episodes.

In contrast to the conventional view of the physician as the expert and “adherence” as a measure of good patient behavior with respect to following their prescribed treatment regimen, recent literature suggests the term concordance to capture a more collaborative partnership between patients and their health care providers.22 This paradigm is congruent with the approach of the BCHAT, which aims to support the autonomy of patients in all aspects of decisions related to the management of their hemophilia. Autonomy support, a key motivational interviewing concept, is emphasized by the team through eliciting the patient’s views and priorities, setting the agenda collaboratively, seeking permission before offering information or suggestions, and resisting the urge to persuade or convince.23

Viewing the patient as a true partner whose imperatives dictate care contrasts with the “physician-as-expert” paradigm. The reality that health-related behavior change is actually more about the patient than clinicians may be difficult for some to accept.24 Many health systems value the top-down organizational approach to service delivery that places the patient on the receiving end of the service/health system benefit. However, in the BCHAT experience, the co-piloting approach leads to a prophylaxis plan that is designed by and makes sense to the patient, and to which the patient is more likely to adhere. Autonomy support occurs within the scope of comprehensive hemophilia and medical care and, thus, remains in accordance with care standards. Should patients identify issues and solutions that fall outside safe and reasonable clinical care, these are clearly identified and patients are offered the opportunity to explore options within acceptable standards of care.

Men born with a serious and potentially life-threatening inherited condition, forced to self-assess and manage at an early age, may align well with an approach that emphasizes autonomy support. This approach allows the patient to remain independent, which fits well with masculinity ideals within the context of managing a chronic condition such as hemophilia.25

While working in an environment with both dynamic and static variables, teams of health care professionals establish a unique but functional practice style. Inherent personality traits, professional and life experience, exposure to prior role models, and group dynamics all affect how comfortably the team performs within this framework. Also noted by this team was a perceived impact of a historical clinic funding model where the group felt both pressure and motivation to adapt in a way that resulted in best clinical care. Without this environmental pressure it is possible the team would not have adapted so significantly toward this more meaningful practice style. Flexibility was a key feature of this teams’ adaptation. While this style may not be fully translatable to other clinics, some elements have the potential to increase patient and clinic team member satisfaction if implemented elsewhere, however, this would require validation through further study.

To our knowledge, this is the first description of a hemophilia team’s roles and processes utilized to partner or “co-pilot” with patients as they design and implement individualized prophylaxis regimens to manage their hemophilia. There are several important limitations regarding the results of the BCHAT focus group work that should be identified. It is impossible to definitively conclude that the team’s approach is leading to improved outcomes. It is possible that speaking with team members individually may have led to slightly varied responses, however, the group format seemed to illicit additional ideas and content that was a result of group synergy. The team’s description of roles and processes in their overall approach has not been validated through observation. Finally, the patient perception of this process has not been measured to date.

Conclusion

Hemophilia care teams strive to partner with patients in a manner that facilitates optimal outcomes with respect to bleed prevention. This study identifies several process elements that could be potentially replicated in other settings to improve patient outcomes. The engagement of patients in designing and implementing their prophylaxis regimen is likely to be a critical factor in the reduction or elimination of bleeding episodes. The exact nature of the relationship between comprehensive care team interventions and achievement of this success should be the focus of further study.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded through the University of British Columbia Bleeding Disorders Collaboratory. Focus group facilitation and analysis was performed by Helen Leask from Journey Dx. Helen Leask and Jennifer Pereira from Journey Dx also consulted with the authors regarding the study design.

Footnotes

Author contributions

DG and SJ designed the study and wrote the paper. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19(1):e1–e47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EGD. The hemophilias – from royal genes to gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(23):1773–1779. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermans C, De Moerloose P. Management of acute haemarthrosis in haemophilia A without inhibitors: literature review, European survey and recommendations. Haemophilia. 2011;17:383–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elander J. A review of the evidence about behavioural and psychological aspects of chronic joint pain among people with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20:168–175. doi: 10.1111/hae.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson SC, Yang M, Minuk L, et al. Prophylaxis in older Canadian adults with hemophilia A: lessons and more questions. BMC Hematol. 2015;15:4. doi: 10.1186/s12878-015-0022-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson SC, Yang M, Minuk L, et al. Patterns of tertiary prophylaxis in Canadian adults with severe and moderately severe haemophilia B. Haemophilia. 2014;20(3):e199–e204. doi: 10.1111/hae.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins PW, Fischer K, Morfini M, Blanchette VS, Bjorkman S. International Prophylaxis Study Group Pharmacokinetics Expert Working Group. Implications of coagulation factor VIII and IX pharmacokinetics in the prophylactic treatment of haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2011;17(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tagliaferri A, Franchini M, Coppola A, et al. Effects of secondary prophylaxis started in adolescent and adult haemophiliacs. Haemophilia. 2008;14(5):945–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins P, Faradji A, Morfini M, Enriquez MM, Schwartz L. Efficacy and safety of secondary prophylactic vs on-demand sucrose-formulated recombinant factor VIII treatment in adults with severe hemophilia A: results from a 13-month crossover study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(1):83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagliaferri A, Franca Rivolta G, Rossetti G, Pattacini C, Gandini G, Franchini M. Experience of secondary prophylaxis in 20 adolescent and adult Italian hemophiliacs. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96(4):542–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khawaji M, Astermark J, Berntorp E. Lifelong prophylaxis in a large cohort of adult patients with severe haemophilia: a beneficial effect on orthopedic outcome and quality of life. Eur J Haematol. 2013;88:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Moerloose P, Urbancik W, van den Berg HM, Richards MA. A survey of adherence to haemophilia therapy in six European countries: results and recommendations. Haemophilia. 2008;14:931–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaughlin JM, Witkop ML, Lambing A, Anderson TL, Munn J, Tortella B. Better adherence to prescripbed treatment regimen is related to less chronic pain among adolescents and young adults with moderate or severe haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20:506–512. doi: 10.1111/hae.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrijvers LH, Uitslager N, Schuurmans MJ, Fischer K. Barriers and motivators of adherence to prophylactic treatment in haemophilia: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2013;19:355–361. doi: 10.1111/hae.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soucie JM, Nuss R, Evatt BL, et al. Mortality among males with hemophilia: relations with source of medical care. Blood. 2000;96:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weatherston A, Gue D. Effectiveness of live telephone support in improving haemophilia clinic attendance. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2014;68:391. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKintosh K, Squire S, Bartholomew C, Camp P, Jackson S. Individualization of prophylaxis in adults improves bleeding outcomes. Haemophilia. 2014;20(Suppl 3):99. [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Association of Facilitators IAF Core Competencies. [Accessed March 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.iaf-world.org/index/certification/CompetenciesforCertification.aspx.

- 19.Institute of Cultural Affairs International [Accessed March 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.ica-international.org/top/top-intro.htm.

- 20.Spencer L. Winning Through Participation. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khair K. Compliance, concordance and adherence: what are we talking about? Haemophilia. 2014;20(5):601–603. doi: 10.1111/hae.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markland D, Ryan RM, Tobin VJ, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. J Social Clin Psychol. 2005;24(6):811–831. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vallis M. Are behavioural interventions doomed to fail? Challenges to self-management support in chronic diseases. Can J Diabetes. 2015;39(4):330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalmar L, Jackson S, Gue D, Oliffe J, Currie L. Men, masculinities and hemophilia. Am J Mens Health. 2015 Jul 29; doi: 10.1177/1557988315596362. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]