Summary

Recent studies of bacterial cellulose biosynthesis, including structural characterization of a functional cellulose synthase complex, provided the first mechanistic insight into this fascinating process. In most studied bacteria, just two subunits, BcsA and BcsB, are necessary and sufficient for the formation of the polysaccharide chain in vitro. Other subunits – which differ among various taxa – affect the enzymatic activity and product yield in vivo by modulating expression of biosynthesis apparatus, export of the nascent β-D-glucan polymer to the cell surface, and the organization of cellulose fibers into a higher-order structure. These auxiliary subunits play key roles in determining the quantity and structure of the resulting biofilm, which is particularly important for interactions of bacteria with higher organisms that lead to rhizosphere colonization and modulate virulence of cellulose-producing bacterial pathogens inside and outside of host cells. Here we review the organization of four principal types of cellulose synthase operons found in various bacterial genomes, identify additional bcs genes that encode likely components of the cellulose biosynthesis and secretion machinery, and propose a unified nomenclature for these genes and subunits. We also discuss the role of cellulose as a key component of biofilms formed by a variety of free-living and pathogenic bacteria and, for the latter, in the choice between acute infection and persistence in the host.

Keywords: bacterial genomes, bacterial host interaction, biofilm structure, environmental bacteria, polysaccharide export, nanocellulose

Cellulose production

Cellulose, poly-β-(1→4)-D-glucose, is the key component of plant cell walls and the most abundant biopolymer on this planet. In fact, it was the view of the cellulose ‘cells’ in cork that prompted Robert Hooke to coin the term cell in the first place. Cellulose is incredibly stable and can withstand washing in strong hot acid or alkali, heating, stretching, and other challenges. You are probably reading this text printed on paper, wearing a cotton T-shirt, and sitting in a wooden chair by a wooden table, which all consist largely of cellulose. While most cellulose on this planet is now being produced by plant cellulose synthase complexes, this enzyme clearly has bacterial origin: there is no doubt that its genes have been acquired by plants from cyanobacterial ancestors of their chloroplasts [1, 2].

Being a major component of the global carbon cycle, cellulose is a favorite substrate for many diverse bacteria and fungi; for higher organisms, including cows that carry cellulolytic bacteria in their rumen; and also for biotechnologists that investigate ways of converting cellulose into biofuel and various bioactive compounds. Despite the recent success in elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of cellulose biosynthesis in plants, many aspects of this process still remain obscure, particularly the mechanisms of cellular export of the nascent polysaccharide chain and arrangement of the cellulose fibrils into a quasi-crystalline structure [3–5]. Bacterial cellulose biosynthesis has long been used as a simpler and genetically tractable model to study its biosynthesis in plants. Even after this model system became dispensable, studies of bacterial cellulose biosynthesis proved extremely important in their own right, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms of polysaccharide export, as well as regulation of bacterial cell responses to oxygen and nitric oxide (NO), cell motility, cell-cell interactions, biofilm formation and dispersal, and a variety of other environmental challenges. Cellulose biosynthesis has been documented in a wide variety of bacteria, including the nitrogen-fixing plant symbiont Rhizobium leguminosarum, soil bacteria Burkholderia spp. and Pseudomonas putida, plant pathogens Dickeya dadantii, Erwinia chrysanthemi and tumor-producing Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and the well-known model organisms Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica (Figure 1; [3, 6, 7]). Cellulose and its derivatives have been identified as significant extracellular matrix components of biofilms and play key roles in modulation of virulence of important plant and human pathogens [8, 9].

Figure 1. Ecosystems harboring cellulose-producing bacteria.

A. The Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park. Sulfur-turf mats of hot springs contain cellulose-producing bacteria [81]. Cyanobacteria such as Anabaena and Nostoc, which occur in aquatic and terrestrial habitats, also produce cellulose [1, 30].

B. Interaction of cellulose producing bacteria with plant species. Left: In R. leguminosarum, the nitrogen-fixing endosymbiont of legumes such as the economically important soybean (in figure), cellulose production aids adhesion and infection of root hairs [82, 83]. Middle: A. tumefaciens causes tumors in a broad spectrum of dicotyledonous plants as the preferred host Rosaceae (in figure). Cellulose production stabilizes colonization by the bacteria of the plant surfaces [84]. Right: Fresh produce contaminated with Salmonella enterica and E. coli is an increasing cause of food-borne outbreaks. Cellulose production is required for S. Typhimurium and E. coli O157:H7 to optimally adhere to tomato fruits and alfalfa sprouts, respectively [62, 63].

C. S. Typhimurium rapidly forms biofilms on the chitinous cell walls of Aspergillus niger hyphae [85].

B. and C. In green, purple and red, cellulose producing R. leguminosarum, A. tumefaciens and S. Typhimurium cells.

D. Cellulose production alters the interaction of bacteria with mammalian hosts. Enterobacterial strains isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract produce cellulose [21, 65, 66]. Cellulose production by S. Typhimurium and/or E. coli affects interaction with epithelial and immune cells in in vitro systems [67–69, 72]}.

From a practical standpoint, bacterial synthesis of cellulose (so-called nanocellulose) is seen as a convenient and effective way to produce stable recyclable fibers for use in wound-dressing and in a variety of emerging nanotechnologies [10, 11]. Genomic data revealed unexpected diversity of cellulose synthase operons even in closely related bacteria, indicating substantial differences in cellulose secretion mechanisms. We review here the recent progress and future challenges in understanding the processes of cellulose biosynthesis in various bacterial lineages.

Diversity of the bcs operons

Substrate synthesis for cellulose production starts from the glycolytic intermediate glucose-6-phosphate. The first committed reaction, isomerization of glucose-6-phosphate to glucose-1-phosphate, is catalyzed by phosphoglucomutase (EC 5.4.2.2). Glucose-1-phosphate then reacts with UTP, forming uridine-5′-diphosphate-α-D-glucose (UDP-glucose) in a rate limiting reaction catalyzed by UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (EC 2.7.7.9). Finally, cellulose synthase (BCS, EC 2.4.1.12) transfers glucosyl residues from UDP-glucose to the nascent β-D-1,4-glucan chain. Channeling copious amounts of UDP-glucose to cellulose biosynthesis leads to reprogramming of the cellular metabolism favoring gluconeogenesis [12].

A four-gene bcsABCD operon involved in cellulose biosynthesis (Figure 2) was initially identified in Komagataeibacter (Acetobacter) xylinus (Box 1). Products of the first two genes, BcsA and BcsB (Table 1), were essential for the BCS activity in vitro [13–15]. However, all four proteins were required for maximal cellulose production in vivo, indicating that BcsC and BcsD were involved in exporting the glucan molecules and packing them at the cell surface. BcsC mutants were unable to produce cellulose fibrils, whereas bcsD mutants produced ~40% less cellulose than the wild-type [13]. The K. xylinus bcs locus included three more genes: eng (later renamed bcsZ) and ccpA upstream of bcsABCD genes, and bglX downstream of them (Figure 2, Ia). The products of bcsZ and bglX are an endoglucanase and a β-glucosidase, respectively (Table 2). Such enzymes could be expected to participate in hydrolysis, rather than synthesis, of β-D-glucans, and their roles in cellulose biosynthesis have long remained obscure. The product of the ccpA gene was required for cellulose production, earning it the name of ‘cellulose-complementing protein A’ [16]. It affects the expression levels of BcsB and BcsC, interacts with BcsD, and appears to assist the arrangement of glucan chains into crystalline ribbons [17–19]. Accordingly, we propose renaming this gene bcsH (Table 2).

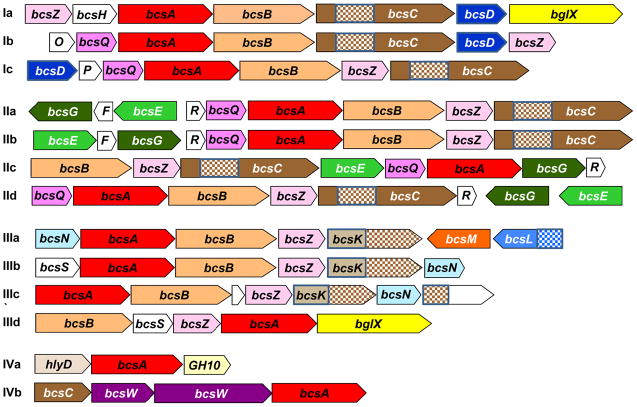

Figure 2. Diversity of the bacterial cellulose synthase (bcs) operons.

Gene designations are as in Tables 1 and 2. The gene symbols are drawn approximately to scale. Empty shapes indicate open reading frames of unknown function, the checkered pattern indicates the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain. The displayed operons are from Komagataeibacter xylinus E25 (Ia, locus tags H845_449 -> H845_455), Dickeya dadantii Ech703 (Ib, Dd703_3897 -> Dd703_3891), Burkholderia phymatum STM815 (Ic, Bphy3259 -> Bphy3253), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (IIa, bcsR -> bcsC, bcsE -> bcsG), Pseudomonas putida KT2440 (IIb, Pput_2132 -> Pput_2138), Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344 (IIc, BMAA1590 - > BMAA1584), Chromobacterium violaceum ATCC 12472 (IId, CV_2672 -> CV_2673, CV_2679 - > CV_2674), Agrobacterium fabrum C58 (IIIa, Atu8187 -> Atu8186, Atu3302 -> Atu3303), Methylobacterium extorquens PA1 (IIIb, Mext1366 -> Mext1371), Azospirillum lipoferum 4B (IIIc, AZOLI_p30428 -> AZOLI_p30422), Acidiphilium cryptum JF-5 (IIId, Acry_0572 -> Acry_0568), Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102 (IVa, Npun_F6499 -> Npun_F6501), and Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 (IVb, alr3754 -> alr3757).

Box 1. A brief history of cellulose synthase.

Bacterial cellulose biosynthesis has been observed many years ago by ancient Chinese growing the so-called Kombucha tea mushroom (Figure I), a syntrophic colony of acetic acid bacteria and yeast, which metabolizes sugar to produce a slightly acidic tea-colored drink and forms a thick cellulosic mat at its surface [86]. Cellulose was first described in plants in 1838 by French scientist Anselme Payen, in whose memory American Chemical Society has established an annual award (see http://cell.sites.acs.org/anselmepayenaward.htm). Thirty years later, British chemist Adrian J. Brown identified cellulose as a key component of the gelatinous pellicle formed upon vinegar fermentation by “an acetic ferment, Bacterium xylinum” [87]. The cellulose-producing acetic acid bacterium, discovered by Brown, proved to be a very convenient model organism for studying cellulose biosynthesis. Over the years, this organism has been known under a variety of names, including Acetobacter xylinum and Gluconacetobacter xylinus. Two years ago it was renamed once again, to Komagataeibacter xylinus [88], and is referred to here as K. xylinus. However, many publications still refer to this organism as G. xylinus; this is also true for its recently sequenced genome (GenBank accession CP004360). Genomes of several closely related bacteria are also available (Table I).

The culture of K. xylinus growing in liquid media is extremely efficient in producing a surface pellicle that consists of pure cellulose fibers [76]. Studies of the cellulose biosynthesis by K. xylinus led to the purification of the respective enzyme complex and the identification of its activator, cyclic dimeric (3′→5′) guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP), which proved to be a universal bacterial second messenger that also regulates biofilm formation, motility, virulence, the cell cycle, bacterial cell differentiation, and other fundamental physiological processes in a wide variety of bacteria [9]. Cellulose and its derivatives have been identified as significant extracellular matrix components of biofilms and play key roles in modulation of virulence of important plant and human pathogens [8, 9].

When did cellulose first appear on this planet? It is being produced by many diverse bacteria including members of the cyanobacterial lineage, which apparently branched from other bacteria as early as 3.0–3.5 billion year ago [1, 30]. As cellulose protects against environmental stresses such as UV radiation and desiccation and is found in modern bacteria-containing hot spring sulfur-turf mats [81, 89], it was even proposed as a potential biosignature for detecting signs of life in extraterrestrial rock materials [90].

Figure I.

Kombucha tea mushroom, a syntrophic community of yeast and acetic acid bacteria of the Gluconacetobacter/Komagataeibacter group [96, 99].

Table I.

Genome sequences of the cellulose producing Gluconacetobacter (Komagataeibacter) species

| Organism name (latest) | TaxID | Genome | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | GenBank entry | Contigs | Total size, bp | Encoded proteins | |||

| Komagataeibacter xylinus E25 | 1296990 | Comp- lete | CP004360 - CP004365 | 6a | 3,447,425 | 3,674 | [91] |

| Komagataeibacter medellinensis NBRC 3288b | 634177 | Comp- lete | AP012159 - AP012166 | 8a | 3,513,191 | 3,195 | [92] |

| Gluconobacter oxydans DSM 3504 | 1288313 | Comp- lete | CP004373, AJ428837 | 2a | 2,886,777 | 2,463 | – |

| Gluconacetobacter sp. SXCC-1 | 1004836 | Draft | AFCH00000000 | 64 | 4,233,336 | 4,895 | [93] |

| Komagataeibacter hansenii ATCC 23769 c | 714995 | Draft | ADTV01000000 | 71 | 3,636,659 | 3,303 | [94] |

| Komagataeibacter europaeus LMG 18890 | 940283 | Draft | CADP00000000 | 321 | 4,227,398 | 3,485 | [95] |

| Komagataeibacter europaeus LMG 18494 | 940284 | Draft | CADR00000000 | 216 | 3,991,281 | 3,312 | [95] |

| Komagataeibacter europaeus 5P3 | 940285 | Draft | CADS00000000 | 256 | 3,989,313 | 3,364 | [95] |

| Komagataeibacter oboediens 174Bp2 | 940286 | Draft | CADT00000000 | 200 | 4,181,473 | 3,355 | [95] |

| Komagataeibacter rhaeticus AF1 | 1432055 | Draft | JDTI00000000 | 225 | 3,939,137 | 3,358 | [96] |

| Komagataeibacter kakiaceti JCM 25156 | 1234672 | Draft | BAIO00000000 | 947 | 3,133,102 | 2,314 | [97] |

Table 1.

Products of the core genes of various cellulose synthase operons

| Protein name | Synonyms | Length, aa | Operon type | UniProt example | Pfam domain name, entry codea | Structureb | Functional annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BcsA | YhjO, CelA | 750–870 | I, II, III, IV | P37653 | Glycos_transf_2 (PF00535 or PF13641), PilZ (PF07238) | 4HG6 | Cellulose synthase catalytic subunit A |

| BcsB | YhjN, CelB | 770–800 | I, II, III | P37652 | BcsB (PF03170) | 4HG6 | Cellulose synthase subunit Bc (periplasmic) |

| BcsC | YhjL, BcsS | 1150 | I, II | P37650 | TPR (PF13414), BcsC_C (PF05420) | 3E4B, 4AZL | Cellulose synthase subunit C, spans periplasm and outer membrane |

| BcsD | CesD, AcsD | 155 | I | P19451 | BcsD (PF03500) | 3A8E | Cellulose synthase subunit D (periplasmic) |

| BcsE | YhjS | 500–750 | II | Q8ZLB5 | DUF2819 (PF10995) | – | Cellulose synthase cytoplasmic subunit E, binds c-di-GMP [43]d |

| BcsF | YhjT | 60 | II | Q7CPI8 | DUF2636 (PF11120) | – | Membrane-anchored subunit (1 TM segment) |

| BcsG | YhjU | 550 | II | Q7CPI7 | DUF3260 (PF11658) | – | Contains 4 TM segments and a periplasmic AlkP domain |

| BcsQ | YhjQ, WssA | 250 | I, II | Q8ZLB6 | YhjQ (PF06564) | 1G3Qe | ParA/MinD-related NTPase, may localize BCS at the cell polee |

| BcsR | YhjR | 65 | II | P0ADJ3 | DUF2629 (PF10945) | – | Likely regulatory subunit |

| BcsZ | CelA, CelC, YhjM | 370 | I, II, III | Q8ZLB7 | Glyco_hydro_8 (PF01270) | 1WZZ 3QXQ | Endo-β-1,4-glucanase (cellulase), periplasmic |

The names and codes of the respective protein domains in the Pfam protein families database (http://pfam.xfam.org/, [45]). In the Pfam release 28 (May 2015), the DUF (domain of unknown function) names have been replaced with the names from the left column.

PDB IDs are given for available structures. Structures of homologous proteins are shown in italics.

BcsB is often mis-annotated as a c-di-GMP-binding regulatory subunit, divalent ion tolerance protein CutA, or cytochrome c biogenesis protein CcmF.

BcsE is often mis-annotated as a metalloprotease.

1G3Q is a structure of BscQ-related ATPase MinD. Based on the properties of a bcsQ mutant [39], BcsQ is often (mis)annotated as either a cell division protein or an ATPase involved in chromosome partitioning.

Table 2.

Products of lineage-specific genes in various cellulose synthase operons

| Protein name | Synonyms | Length, aa | Operon type | UniProt example | Pfam domain name, entry code | Functional annotation, comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BcsH | CcpA, ORF2 | 340 | Ia | Q76KK0 | CcpA (PF17040)c | Cellulose-complementing protein A, specific for acetobacteriaa |

| BglX | BglXa | 730 | Ia | Q8RTY7 | Fn3-like (PF14310), GH3 (PF00933), | β-glucosidase, glycosyl hydrolase family 3, secreted |

| BcsO | – | 200 | Ib | D4IFF8 | BcsO (PF17037)c | Unknown, specific for enterobacterial type Ib bcs operons |

| BcsP | – | 180 | Ic | Q2KWQ2 | BcsP (PF10945)c | Unknown, specific for β-proteobacterial type Ic bcs operons |

| BcsK | CelG | 750 | III | Q8U4V1 | TPR (PF13432) | Likely interacts with peptidoglycan |

| BcsL | CelD | 550 | IIIa | Q7CS43 | Acetyltransf (PF13480), TPR (PF13432) | Acetyltransferase |

| BcsM | CelE | 380 | IIIa | Q7CS44 | Peptidase_M20 (PF01546) | Zn-dependent amidohydrolase, may deacylate modified glucose residues |

| BcsN | – | 330 | III | B9K194 | BscN (PF17038)c | Unknown, periplasmic, membrane-anchored (1 TM), specific for α-proteobacteria |

| BcsS | – | 250 | III | A9W2G1 | BcsS (PF17036)c | Unknown, secreted, specific for α-proteobacteria |

| BcsT | – | 620 | III | A9CEZ9 | GT_21 (PF13506) | Membrane protein (8 TM) with a cytoplasmic glycosyltransferase domain |

| BcsU | CelJ | 170 | III | Q7CS50 | DUF995 (PF06191) | Unknown, secreted, specific for Rhizobiales |

| BcsV | CelK | 320 | III | Q7CS49 | GH26 (PF02156) | Beta-mannanase, secreted, specific for Rhizobiales |

| BcsW | – | 440 | IV | Q8YQR4 | DUF3131 (PF11329) | Unknown, predicted periplasmic |

| BcsX | WssF | 260 | – | Q9WX69 | SGNH_hydrolase (IPR013830) | Probable cellulose deacylaseb |

| BcsY | – | 380 | – | Q9WX70 | Acyl_transf_3 (PF01757) | Membrane protein (10 TM), probable cellulose acylase |

BcsH is often mis-annotated as an endoglucanase or β-glucosidase.

BcsX is often mis-annotated as cell division protein FtsQ.

These protein families have appeared in the release 28 (May 2015) of the Pfam database [45].

Some strains of K. xylinus also have a second bcs operon which encodes a single long BcsAB fusion protein, and two additional genes, bcsX and bcsY. Their products have not been characterized, although sequence comparisons predicted that BcsY could function as a transacylase, probably participating in the production of acetylcellulose or a similarly modified polysaccharide [20].

An early analysis of the cellulose synthase operons in E. coli and S. enterica [6, 21] indicated the presence of the same bcsA, bcsB, and bcsC genes and two additional genes, yhjQ and bcsZ (Figure 2, IIa). This locus also contains a divergent operon, bcsEFG, which is also required for cellulose production [22, 23]. Subsequent analysis revealed the existence of an additional short gene, yhjR, preceding the yhjQ-bcsABZC operon, and showed that yhjQ is required for cellulose biosynthesis [24]. Accordingly, yhjQ gene has been renamed bcsQ. More recently, deletion of yhjR has been shown to affect biofilm formation, indicating a role in cellulose production [23].

In A. tumefaciens, R. leguminosarum, and many other bacteria, bcs operons include bcsA and bcsB genes but lack bcsC (Figure 2, IIIa) [25–27]. The bcs locus of A. tumefaciens includes two convergent operons, celABCG and celDE. The first three genes are orthologs of bcsA, bcsB, and bcsZ, respectively, whereas the other three appear to be specific for this kind of operon. Of these, celE was essential for cellulose formation [27]. Similar operons are also seen in members of the Actinobacteria and Firmicutes phyla, which lack the outer membrane and apparently employ cellulose secretion machineries that are quite distinct from those seen in proteobacteria.

Classification of the bcs operons

The diversity of bcs operons prompted several attempts to classify them [6, 7, 20]. Here, we propose dividing all characterized bcs operons into three major types, found, respectively, in K. xylinus, E. coli, and A. tumefaciens (Figure 2). Each of these major types of bcs operons can be divided into several subtypes, based on the gene order and gene content, as shown in Figure 2.

The distinguishing feature of the first type of bcs operons is the presence of the bcsD gene, whose product is believed to be localized in the periplasm and appears to direct the glucan chain towards the pores in the outer membrane [28, 29]. Type I bcs operons are found in certain representatives of alpha, beta, and gamma subdivisions of Proteobacteria (Figure 3). In some type Ib operons, bcsA and bcsB genes are fused, resulting in a single catalytic subunit of ~1,500 amino acid residues, which might be post-translationally cleaved.

Figure 3. Presence of bcs genes in selected proteobacterial genomes.

When bcs genes are present in a genome these are shown by colored boxes labeled with the last letter of the gene (for example, bcsA is labeled A). The boxes are colored the same way as genes in Figure 1. The letters in parentheses indicate genes that have been missed in the genome annotation, the X sign indicates genes with frameshift mutations. Names of organisms experimentally shown to produce cellulose are in bold.

The second, E. coli-like type of bcs operons is widespread among the members of beta and gamma subdivisions of Proteobacteria. Its distinguishing feature is the presence of the bcsE and bcsG genes (and the absence of bcsD). Two short genes, bcsF and yhjR, are often present but may be either missing or just not annotated in the genomic sequence.

The third type of bcs operons includes bcsA and bcsB genes but not bcsD, bcsE, or bcsG (Figure 2). Such operons usually include bcsZ and an additional gene, referred to here as bcsK, that encodes a BcsC-like TRP domain-containing protein but without the BcsC_C domain (see below).

Finally, there is a class of bcs-like operons that contain bcsA but lack bcsB and most other bcs genes. Such bcsB-missing operons have been seen in cellulose-producing cyanobacteria Anabaena sp. PCC7120 and Thermosynechococcus vulcanus [1, 30]. In the absence of BcsB, binding of the BcsA-synthesized nascent glucan polymer on the outer face of the membrane and its translocation outside the cell must be carried out by different, yet uncharacterized proteins. Potential candidates include the membrane-fusion family protein HlyD (Figure 2, IVa) and an uncharacterized protein BcsW, which are encoded in the same operons as bcsA. Thus, type III and type IV bcs operons encode potential new components of the cellulose export machinery, whose functions remain to be elucidated. Obviously, type IV operons represent a mixed bag and additional operon types could be identified once their BCS products are experimentally characterized.

Acquisition and loss of bcs genes

Some organisms, including opportunistic human pathogens Klebsiella pneumoniae and Raoultella ornithinolytica, carry both type I and type II bcs operons, whereas their close relatives carry either a single bcs operon or none at all (Figure 3). The presence of two bcs operons likely results from lateral gene transfer with extra bcs genes providing the organism with greater flexibility with respect to cellulose production and biofilm formation. A more common picture is acquisition and loss of individual bcs genes, which may result in substantial differences between species from the same genus (Figure 3). The genus Burkholderia exhibits the greatest diversity with at least four patterns of bcs genes. In Rhizobium etli and Pseudomonas syringae, bcs gene patterns differ even within species. The significance of such unusual gene arrangements of bcs genes remains to be studied.

Another interesting development is inactivation of certain bcs genes that is seen in the genus Shigella (Figure 3). While Shigella boydii carries the same bcs operon as E. coli, three other species have frameshift mutations in bcsA (Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei) or other bcs genes (Shigella dysenteriae) that should prevent them from producing cellulose. The loss of cellulose biosynthesis is probably an adaptation of these organisms to their parasitic lifestyle.

Structure and functions of individual subunits

Bacterial synthesis of cellulose occurs at the cytoplasmic side of the (inner) membrane and elongation of the nascent molecule must be tightly linked to its secretion. Accordingly, in addition to the catalytic glucosyltransferase subunit BcsA, BCS complexes include a variety of subunits that ensure orderly export of the growing polysaccharide chain. We present here a brief description of the BCS subunits.

BcsA and BcsB

BcsA and BcsB are two catalytic subunits that are present in all BCS enzymes experimentally characterized so far. Crystal structure of the BcsA-BcsB complex from Rhodobacter sphaeroides has been solved recently [31]. BcsA consists of eight transmembrane (TM) segments and two large cytoplasmic domains, a glycosyltransferase domain in the middle and a C-terminal fragment that contains the c-di-GMP-binding PilZ domain (Figure 4). BcsB is located in the periplasm and is anchored in the membrane by a single transmembrane helix. An intriguing feature of the BcsAB structure is a channel leading from the glycosyltransferase domain across the membrane and into the periplasm [31]. The size of this channel allows it to accommodate several glucoside units, indicating that BCS likely couples addition of new glucoside residues to the nascent glucan molecule with its translocation across the membrane and into the periplasm [31]. In K. xylinus, the BCS complex is localized along the longitudinal axis of the cell, which might aid arrangement of glucan chains into crystalline cellulose ribbons [29].

Figure 4. Organization of the cellulose synthase complexes.

A. Predicted structure of the type I cellulose synthase holoenzyme, combined 3D structures of BcsA (PDB 4P02, red), BcsB (PDB 4HG6, tan), AlgK (PDB 3E4B), AlgE (PDB 4AZL), and BcsD (PDB 3A8E, blue), see [31–34]. The c-di-GMP molecule bound to BcsA is shown in cyan, the nascent glucan molecule is in green. Abbreviations: IM, inner membrane; PG, peptidoglycan layer; OM, outer membrane.

B – D. Proposed organization of the BCS complexes from Komagataeibacter xylinus (B), Escherichia coli (C), and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (D), see [33, 34, 37, 38] for related models. All BCS subunits are colored the same way as their respective genes in Figure 2. The labels indicate the names of the proteins in Tables 2 and 3.

BcsC and BcsK

BcsC is a periplasmic protein that consists of an N-terminal α-helical part formed by several tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains and a C-terminal part that is structurally similar to the β-barrels of outer membrane proteins. This organization is similar to that of AlgK-AlgE pair of proteins that participate in the export of alginate from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and have known 3D structures [33, 34]. In P. aeruginosa, AlgK interacts with the peptidoglycan layer and organizes the entire alginate biosynthesis and secretion complex [35, 36], while AlgE forms an outer membrane pore [37, 38]. Accordingly, the TPR-containing N-terminal part of BcsC is believed to interact with peptidoglycan and other BSC components, while its C-terminal β-barrel domain is likely located in the outer membrane, forming a channel that guides the nascent glucan out of the cell [33, 38].

Some type III bcs operons encode a different TPR-containing protein, referred to as CelG in A. tumefaciens [27] and renamed here BcsK (Table 2). Its functions are probably the same as those of AlgK and the N-terminal part of BcsC, i.e. interacting with the peptidoglycan and organizing the entire cellulose secretion complex.

BcsD and BcsH

BcsD is a periplasmic protein that oligomerizes to form a cylindrical octamer ~90 Å in diameter with a huge central pore that can accommodate up to 4 separate glucan molecules [28]. BcsD seems to be required for the arrangement of the BCS complex along the longitudinal cell axis [29].

Another important protein is the ‘cellulose complementing factor’ CcpA (renamed here BcsH). It is encoded exclusively in the Komagataeibacter/Gluconacetobacter lineage and is required for the BCS activity in K. xylinus and Komagataeibacter hansenii [16–18]. It has been shown to interact with BcsD in the periplasm. This unique organization might account for the extremely high activity of the K. xylinus BCS.

BcsQ

In E. coli, BCS is localized to the cell pole, which requires the BcsQ protein [24], a predicted ATPase of the MinD/ParA/Soj superfamily. This protein is encoded in most bcs operons (Figure 2) and is likely to determine cellular localization of the respective BCS complexes. Insertional inactivation of the yhjQ (bcsQ) gene caused abnormal cell division, leading to cell filamentation [39]. Based on these observations and its similarity to MinD, BcsQ is often mis-annotated as a cell division protein; the bcs operon structures shown in Figure 2 should help in resolving this confusion.

BcsZ and BglX

The widespread presence in the bcs operons of the cellulase-encoding bcsZ gene (Figure 2) seems counterintuitive and, in Arabidopsis, has been aptly referred to as “a cat among the pigeons” [40]. Indeed, BcsZs from several bacteria have been shown to possess an endo-β-1,4-glucanase (cellulase) activity and E. coli protein was even crystallized in a complex with the substrate cellopentaose [41]. One clue to its function is the predicted periplasmic and extracellular location of BcsZ, which suggests a role in regulating cellulose production. Disruption of the K. xylinus bcsZ gene decreased the overall production of cellulose and caused irregular packing of its fibrils [19]. In R. leguminosarum, bcsZ mutants produced longer cellulose micro-fibrils but had a reduced ability to form biofilms [42]. A similar proof-reading role could be ascribed to BglX, a β-glucosidase that is occasionally encoded in the bcs operons, e.g. in K. xylinus (Figure 2). Of note, in R. leguminosarum, BcsZ has a function of its own, as it is required to initiate successful symbiosis through selective digestion of the non-crystalline cellulose of the root hair wall at the tip [42].

BcsE and BcsG

BcsE and BcsG are encoded in type II bcs operons and are required for optimal cellulose synthesis by the respective enzymes [22, 43]. BcsE has been shown to bind c-di-GMP and thus provide an additional level of regulation of cellulose production [43]. BcsG combines an N-terminal membrane portion with a C-terminal periplasmic domain that belongs to the alkaline phosphatase superfamily [44]. Its exact role in cellulose biosynthesis remains to be characterized.

BcsO and BcsP

BcsO and BcsP are proline-rich proteins of unknown function encoded in, respectively, enterobacterial (Figure 2, Ib) and β-proteobacterial (Figure 2, Ic) type I bcs operons. The N-terminal region of BcsP is similar to BcsR and has been assigned to the same Pfam domain PF10945 [45] (Table 2).

Table 2 lists several more uncharacterized proteins that are encoded within bcs-like operons. Their likely involvement in cellulose production and/or modification makes them attractive targets for future experimental studies.

Organization of the BCS holoenzymes

The recent success in solving the crystal structures of the BcsA-BcsB complex from R. sphaeroides [31], the BcsD subunit from K. xylinus, and of the BcsC-like AlgK protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa [28, 33], makes it possible to imagine the structure of the entire type I BCS holoenzyme (Figure 4a). The structural organization of type II and III BCS enzymes is far less understood. The cartoons on Figure 4b represent proposed positions of their subunits based on the presence of predicted signal peptides and transmembrane segments.

Diversity of cellulose products

The diversity of the bcs operons and the respective enzymes might reflect the diversity of their cellulose products. Some bcs-like operons encode BcsA-like glucosyltransferases that produce alternative polysaccharides, such as the β-(1→3)-D-glucan curdlan [46] or the mixed-linkage (1→3,1→4)-β-D-glucan [47]. Another example is acetylated cellulose produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens [8, 48]. But even if the glucan product is a chemically simple β-1,4-glucose polymer, glucan chains get arranged into complex micro-fibrils and ribbons, which can have different types of crystallinity. Crystalline cellulose can come in different allomorphs with linear glucan chains packed parallel or anti-parallel and flexibly arranged intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds, whereby cellulose I is the predominant allomorph. While the cellulose synthesized by K. xylinus has crystalline structure, enterobacteria appear to produce mostly non-crystalline (amorphous) cellulose. One approach to address the question of the structural diversity of cellulose operons and their products is heterologous expression of the BCS complex [49].

Regulation of cellulose biosynthesis

Bacterial cellulose biosynthesis is regulated on both transcriptional and post-translational levels. Expression of the bcs genes appears to be controlled by different regulators in different bacteria (e.g. by Fis in D. dadantii), but is generally stimulated during biofilm formation, as compared to the log phase [21, 50]. The BCS activity in vivo depends on the presence of both BCS subunits and its allosteric regulator c-di-GMP. Accordingly, such transcriptional regulators as Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium MlrA and the biofilm regulator CsgD appear to modulate cellulose biosynthesis indirectly by regulating expression of c-di-GMP synthases (diguanylate cyclases, DGCs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs) [9, 51, 52]. Early studies of the cellulose biosynthesis in K. xylinus revealed that c-di-GMP could stimulate it almost 100-fold [3]. The mechanism of this regulation has been uncovered only recently, when the crystal structure of the BcsAB complex revealed the enzyme in an autoinhibitory state with a conserved gating loop interacting with the c-di-GMP-binding PilZ domain [32]. Upon c-di-GMP binding to the PilZ domain, the active site becomes accessible for its UDP-glucose substrate.

In K. xylinus, three DGCs provided approximately 80%, 14% and 4% of the total activity [53]. Still, mutants lacking the physiologically dominant DGC1 retained ~85% of cellulose production, indicating that c-di-GMP production by DGC2 and DGC3 was sufficient for activation of the BCS [53]. Accordingly, while most bacteria encode numerous DGCs and PDEs (see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Complete_Genomes/c-di-GMP.html), overexpression of almost any DGC could in principle produce enough c-di-GMP to stimulate cellulose production [51]. However, recent experiments showed that only certain DGCs serve as actual regulators of BCS in vivo. Thus, in E. coli and S. Typhimurium, cellulose biosynthesis is regulated primarily by two DGCs, AdrA (STM0385) and YedQ (STM1987) [51, 54, 55]. DGCs and PDEs that specifically regulate cellulose biosynthesis have also been seen in other bacteria [25, 56–58]. The nature of such dominance of certain specific DGCs is not known. It is possible that AdrA and YedQ are capable of directly binding to the cellulose synthase complex to deliver c-di-GMP straight to its BcsA target or at least produce high local c-di-GMP concentrations at the inner membrane. The recent finding of c-di-GMP binding by BcsE suggests the existence of two different ways of c-di-GMP action: a direct one, through binding to BcsA’s PilZ domain, and an indirect one, mediated by the cytoplasmic c-di-GMP receptor BcsE, which then transfers c-di-GMP to BcsA [32, 43].

Cellular c-di-GMP levels are controlled by numerous DGCs and PDEs that are regulated by a variety of extra- or intracellular parameters. While only few of such signals have been identified, oxygen and NO signaling have been demonstrated to specifically affect cellulose biosynthesis (see [9] for a review). In addition, many DGC and PDE domains are fused with the receiver domains, putting these enzymes under the control of the two-component signal transduction systems [25, 56, 59].

Ecology of cellulose biosynthesis

Besides stability and rigidity, bacterial cellulose has a high capacity of water retention. As a common exopolysaccharide component in the extracellular biofilm matrix of ecologically diverse bacteria, from the thermophilic cyanobacterium T. vulcanus to the gastrointestinal pathogen S. enterica [21, 30], cellulose mediates cell-cell interactions, cell adherence and biofilm formation on biotic and abiotic surfaces [8, 21, 60]. Gradual increase in cellulose production prepares bacteria for surface colonization, as cellulose slows down flagella-associated motility [61]. In mature biofilms, a rigid extracellular matrix termed ‘bacterial wood’ is formed by the interaction of cellulose with amyloid fimbrial components of the biofilm matrix [21]. As for resistance mechanisms, cellulose biosynthesis has specifically been shown to protect from chlorine treatment [51].

Cellulose has a specific role in plant-associated bacteria. Plant symbionts such as P. fluorescens and R. leguminosarum require cellulose production for rhizosphere and phyllosphere persistence and for establishment of tight interactions with host cells [48]. In plant pathogens A. tumefaciens and D. dadantii, cellulose aids colonization of plant surfaces [50]. Interestingly, cellulose is involved in the interaction of the food-born pathogen S. enterica with the soil fungus Aspergillus niger {Balbontin, 2014 #261}, suggesting that cellulose biosynthesis could be a general ecological retention mechanism of soil bacteria via cellulose-chitin interactions.

Food-borne outbreaks due to produce contaminated with microorganisms such as S. enterica and E. coli increased in the last 20 years. Among other genes relevant for biofilm formation, cellulose biosynthesis genes are consistently found as contributing to the adhesion and colonization of consumer-relevant plants such as tomato, lettuce, and alfalfa sprouts [62–64].

Involvement in pathogenicity

Many enterobacterial species of the human gastrointestinal tract such as E. coli, S. enterica and Citrobacter freundii produce cellulose [65, 66], but cellulose production has not been directly demonstrated in the host. Its significance in bacterial host interaction is indicated as adherence to gut epithelial cell lines is affected in a strain dependent way in E. coli [67–69]. Cellulose production inhibits internalization of E. coli and S. Typhimurium by gastrointestinal epithelial cells and proinflammatory cytokine production of epithelial cells induced by flagellin (which activates the innate immune response) [69, 70]. Thus, as in biofilm formation [71], cellulose partially counteracts the interaction of amyloid curli fimbriae with epithelial cells [21, 69, 70]. Surprisingly, in the probiotic strain E. coli Nissle 1917, which does not produce curli fimbriae at body temperature, cellulose biosynthesis has opposite effects as in the commensal E. coli strain producing curli [67, 69].

In acute disease situations, cellulose biosynthesis is tightly regulated, while enhanced production leads to a decrease in virulence properties suggesting that cellulose is an anti-virulence factor [72]. For example, in S. Typhimurium, invasion of epithelial cells, a key virulence phenotype, is effectively suppressed upon deletion of phosphodiesterases, which can be partially relieved through deletion of BcsA [73]. In the mouse model of urinary tract infection, dysregulation of the c-di-GMP signaling network in an uropathogenic E. coli strain, caused by deletion of a negative regulator of the DGC YfiN, resulted in decreased virulence, which could be relieved by combined deletion of BCS and the biofilm regulator CsgD [74]. Cellulose biosynthesis also plays a role in the regulation of growth of intracellular bacteria. Indeed, S. Typhimurium produces cellulose inside macrophages, which restricts bacterial growth [72]. Besides providing a trade-off between virulence and persistence in host cells, production of immunologically inert cellulose might mask interaction between bacterial adhesins and host receptors and thereby prevent activation of immune response.

Taken together, these data suggest the existence of both c-di-GMP-dependent and independent pathways to suppress cellulose biosynthesis in bacterial-host interactions. The c-di-GMP signaling network cooperatively regulates suppression of cellulose biosynthesis in acute infections through balanced expression of DGCs and PDEs. Whether cellulose is a virulence factor in chronic infections as part of the biofilm phenotype remains to be established. However, the recent observation of the requirement of the expression of the cellulose-associated rdar (red, dry and rough colony morphology [52]) biofilm of S. Typhimurium for colonization of solid tumors [75] certainly points in this direction.

Applications of cellulose synthase

From the bioengineering perspective, bacterial cellulose has certain advantages over plant cellulose, including its high purity, high capacity of water retention, and the nano-scale arrangement of the cellulose fibrils. These features make bacterial cellulose an attractive biocompatible material, which is already commercially available as a wound dressing material for complicated wounds such as skin ulcers [76, 77]. Potential applications of bacterial cellulose and its derivatives also include their use as scaffolds for the replacement of small-diameter blood vessels [78, 79] and as drug delivery systems [77, 80], as well as membranes and filters. At this time, only K. xylinus-related bacteria produce cellulose in amounts sufficient for industrial use [80]. However, studies of novel bacterial strains and optimization of culture conditions promise to make commercial production of bacterial cellulose and/or it derivatives economically feasible in the near future.

Concluding remarks

Plant-derived cellulose is not just the most abundant biopolymer on Earth, it is also the only fully renewable one. Understanding the mechanisms of its synthesis and using this knowledge to optimize energy generation and production of novel industrial and medical materials has long been the dream of many biologists and engineers. Bacterial cellulose biosynthesis, while taking place on a somewhat smaller scale, is of geochemical, ecological, agricultural and medical importance. The recent structural characterization of BCS provides valuable clues to the organization of the cellulose biosynthesis machinery in bacteria and plants. It also opens new avenues of manipulating these systems towards production of new generation of biopolymers in a renewable and economically sustainable fashion. However, the cellulose biosynthesis and secretion machineries of various bacteria are extremely diverse, and there are still many open questions to be addressed (Box 2).

Box 2. Outstanding questions.

What are the functions of the uncharacterized genes in various bcs operons?

What is the stoichiometry of the subunits in various BCS complexes?

How is cellulose biosynthesis regulated? What are the input signals?

What are the mechanisms of cellulose-mediated bacterial adhesion and its role in bacterial-bacterial, bacterial-fungal and bacterial-host interactions?

Are there substantial differences between cellulose macromolecules produced by different organisms and different cellulose synthase complexes?

What kinds of additional exopolysaccharides can be made by cellulose synthase-like proteins?

Will it be possible to produce bacterial cellulose on an industrial scale in an economically efficient way?

How soon will we see cellulose-based nanomaterials with specifically engineered properties?

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Römling lab for comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council Natural Sciences and Engineering, the Karolinska Institutet and Petrus and Augusta Hedlund Foundation (to UR) and the NIH Intramural Research Program at the U.S. National Library of Medicine (MYG).

References

- 1.Nobles DR, et al. Cellulose in cyanobacteria. Origin of vascular plant cellulose synthase? Plant Physiol. 2001;127:529–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nobles DR, Brown RM., Jr The pivotal role of cyanobacteria in the evolution of cellulose synthases and cellulose synthase-like proteins. Cellulose. 2004;11:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross P, et al. Cellulose biosynthesis and function in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:35–58. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.35-58.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slabaugh E, et al. Cellulose synthases: new insights from crystallography and modeling. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McFarlane HE, et al. The cell biology of cellulose synthesis. Annual review of plant biology. 2014;65:69–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Römling U. Molecular biology of cellulose production in bacteria. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jahn CE, et al. The Dickeya dadantii biofilm matrix consists of cellulose nanofibres, and is an emergent property dependent upon the type III secretion system and the cellulose synthesis operon. Microbiology. 2011;157:2733–2744. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiers AJ, et al. Biofilm formation at the air-liquid interface by the Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 wrinkly spreader requires an acetylated form of cellulose. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:15–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Römling U, et al. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gatenholm P, Klemm D. Bacterial nanocellulose as a renewable material for biomedical applications. MRS Bulletin. 2010;35:208–213. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin SP, et al. Biosynthesis, production and applications of bacterial cellulose. Cellulose. 2013;20:2191–2218. [Google Scholar]

- 12.White AP, et al. A global metabolic shift is linked to Salmonella multicellular development. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong HC, et al. Genetic organization of the cellulose synthase operon in Acetobacter xylinum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8130–8134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena IM, et al. Cloning and sequencing of the cellulose synthase catalytic subunit gene of Acetobacter xylinum. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:673–683. doi: 10.1007/BF00016118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omadjela O, et al. BcsA and BcsB form the catalytically active core of bacterial cellulose synthase sufficient for in vitro cellulose synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17856–17861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314063110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Standal R, et al. A new gene required for cellulose production and a gene encoding cellulolytic activity in Acetobacter xylinum are colocalized with the bcs operon. Journal of bacteriology. 1994;176:665–672. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.665-672.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng Y, et al. Identification and characterization of non-cellulose-producing mutants of Gluconacetobacter hansenii generated by Tn5 transposon mutagenesis. Journal of bacteriology. 2013;195:5072–5083. doi: 10.1128/JB.00767-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunagawa N, et al. Cellulose complementing factor (Ccp) is a new member of the cellulose synthase complex (terminal complex) in Acetobacter xylinum. J Biosci Bioeng. 2013;115:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakai T, et al. Formation of highly twisted ribbons in a carboxymethylcellulase gene-disrupted strain of a cellulose-producing bacterium. Journal of bacteriology. 2013;195:958–964. doi: 10.1128/JB.01473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umeda Y, et al. Cloning of cellulose synthase genes from Acetobacter xylinum JCM 7664: implication of a novel set of cellulose synthase genes. DNA Res. 1999;6:109–115. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zogaj X, et al. The multicellular morphotypes of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli produce cellulose as the second component of the extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1452–1463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solano C, et al. Genetic analysis of Salmonella enteritidis biofilm formation: critical role of cellulose. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:793–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serra DO, et al. Cellulose as an architectural element in spatially structured Escherichia coli biofilms. Journal of bacteriology. 2013;195:5540–5554. doi: 10.1128/JB.00946-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Quere B, Ghigo JM. BcsQ is an essential component of the Escherichia coli cellulose biosynthesis apparatus that localizes at the bacterial cell pole. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:724–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ausmees N, et al. Structural and putative regulatory genes involved in cellulose synthesis in Rhizobium leguminosarum bvtrifolii. Microbiology. 1999;145:1253–1262. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthysse AG, et al. Genes required for cellulose synthesis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Journal of bacteriology. 1995;177:1069–1075. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1069-1075.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthysse AG, et al. The effect of cellulose overproduction on binding and biofilm formation on roots by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:1002–1010. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu SQ, et al. Structure of bacterial cellulose synthase subunit D octamer with four inner passageways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17957–17961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta K, et al. Characterization of an acsD disruption mutant provides additional evidence for the hierarchical cell-directed self-assembly of cellulose in Gluconacetobacter xylinus. Cellulose. 2014;22:119–137. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawano Y, et al. Cellulose accumulation and a cellulose synthase gene are responsible for cell aggregation in the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus vulcanus RKN. Plant & cell physiology. 2011;52:957–966. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan JL, et al. Crystallographic snapshot of cellulose synthesis and membrane translocation. Nature. 2013;493:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature11744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan JL, et al. Mechanism of activation of bacterial cellulose synthase by cyclic di-GMP. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2014;21:489–496. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keiski CL, et al. AlgK is a TPR-containing protein and the periplasmic component of a novel exopolysaccharide secretin. Structure. 2010;18:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitney JC, et al. Structural basis for alginate secretion across the bacterial outer membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13083–13088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104984108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rehman ZU, et al. Insights into the assembly of the alginate biosynthesis machinery in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3264–3272. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00460-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rehman ZU, Rehm BH. Dual roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgE in secretion of the virulence factor alginate and formation of the secretion complex. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:2002–2011. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03960-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hay ID, et al. Genetics and regulation of bacterial alginate production. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:2997–3011. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitney JC, Howell PL. Synthase-dependent exopolysaccharide secretion in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends in microbiology. 2013;21:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim MK, et al. The effect of a disrupted yhjQ gene on cellular morphology and cell growth in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;60:134–138. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueda T. Cellulase in cellulose synthase: A cat among the pigeons? Plant Physiol. 2014;165:1397–1398. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.245753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazur O, Zimmer J. Apo- and cellopentaose-bound structures of the bacterial cellulose synthase subunit BcsZ. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17601–17606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robledo M, et al. Role of Rhizobium endoglucanase CelC2 in cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation on plant roots and abiotic surfaces. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:125. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang X, et al. GIL, a new c-di-GMP-binding protein domain involved in regulation of cellulose synthesis in enterobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2014;93:439–452. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. Divergence and convergence in enzyme evolution. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.241976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finn RD, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D222–230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karnezis T, et al. Topological characterization of an inner membrane (1-->3)-b-D-glucan (curdlan) synthase from Agrobacterium sp. strain ATCC31749. Glycobiology. 2003;13:693–706. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez-Mendoza D, et al. Novel mixed-linkage β-glucan activated by c-di-GMP in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E757–E765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421748112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gal M, et al. Genes encoding a cellulosic polymer contribute toward the ecological success of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 on plant surfaces. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:3109–3121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imai T, et al. Functional reconstitution of cellulose synthase in Escherichia coli. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:4206–4213. doi: 10.1021/bm501217g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prigent-Combaret C, et al. The nucleoid-associated protein Fis directly modulates the synthesis of cellulose, an essential component of pellicle-biofilms in the phytopathogenic bacterium Dickeya dadantii. Mol Microbiol. 2012;86:172–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia B, et al. Role of the GGDEF protein family in Salmonella cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:264–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Römling U. Characterization of the rdar morphotype, a multicellular behaviour in Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1234–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4557-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tal R, et al. Three cdg operons control cellular turnover of cyclic di-GMP in Acetobacter xylinum: genetic organization and occurrence of conserved domains in isoenzymes. Journal of bacteriology. 1998;180:4416–4425. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4416-4425.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Römling U, et al. AgfD, the checkpoint of multicellular and aggregative behaviour in Salmonella typhimurium regulates at least two independent pathways. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:10–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Da Re S, Ghigo JM. A CsgD-independent pathway for cellulose production and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology. 2006;188:3073–3087. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.3073-3087.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnhart DM, et al. A signaling pathway involving the diguanylate cyclase CelR and the response regulator DivK controls cellulose synthesis in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Journal of bacteriology. 2014;196:1257–1274. doi: 10.1128/JB.01446-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bassis CM, Visick KL. The cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase BinA negatively regulates cellulose-containing biofilms in Vibrio fischeri. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192:1269–1278. doi: 10.1128/JB.01048-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu J, et al. Genetic analysis of Agrobacterium tumefaciens unipolar polysaccharide production reveals complex integrated control of the motile-to-sessile switch. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:929–948. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galperin MY. Diversity of structure and function of response regulator output domains. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grantcharova N, et al. Bistable expression of CsgD in biofilm development of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192:456–466. doi: 10.1128/JB.01826-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zorraquino V, et al. Coordinated cyclic-di-GMP repression of Salmonella motility through YcgR and cellulose. Journal of bacteriology. 2013;195:417–428. doi: 10.1128/JB.01789-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matthysse AG, et al. Polysaccharides cellulose, poly-b-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, and colanic acid are required for optimal binding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains to alfalfa sprouts and K-12 strains to plastic but not for binding to epithelial cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2384–2390. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01854-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaw RK, et al. Cellulose mediates attachment of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium to tomatoes. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2011;3:569–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yaron S, Römling U. Biofilm formation by enteric pathogens and its role in plant colonization and persistence. Microbial biotechnology. 2014;7:496–516. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zogaj X, et al. Production of cellulose and curli fimbriae by members of the family Enterobacteriaceae isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4151–4158. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4151-4158.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bokranz W, et al. Expression of cellulose and curli fimbriae by Escherichia coli isolated from the gastrointestinal tract. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:1171–1182. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Monteiro C, et al. Characterization of cellulose production in Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 and its biological consequences. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1105–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saldana Z, et al. Synergistic role of curli and cellulose in cell adherence and biofilm formation of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli and identification of Fis as a negative regulator of curli. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:992–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang X, et al. Impact of biofilm matrix components on interaction of commensal Escherichia coli with the gastrointestinal cell line HT-29. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2352–2363. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lamprokostopoulou A, et al. Cyclic di-GMP signalling controls virulence properties of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium at the mucosal lining. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:40–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cegelski L. Bottom-up and top-down solid-state NMR approaches for bacterial biofilm matrix composition. Journal of magnetic resonance. 2015;253:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pontes MH, et al. Salmonella promotes virulence by repressing cellulose production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5183–5188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500989112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ahmad I, et al. Complex c-di-GMP signaling networks mediate transition between virulence properties and biofilm formation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simm R, et al. A role for the EAL-like protein STM1344 in regulation of CsgD expression and motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Journal of bacteriology. 2009;191:3928–3937. doi: 10.1128/JB.00290-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pawar V, et al. Murine solid tumours as a novel model to study bacterial biofilm formation in vivo. J Intern Med. 2014;276:130–139. doi: 10.1111/joim.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Czaja W, et al. Microbial cellulose--the natural power to heal wounds. Biomaterials. 2006;27:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abeer MM, et al. A review of bacterial cellulose-based drug delivery systems: their biochemistry, current approaches and future prospects. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;66:1047–1061. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bottan S, et al. Surface-structured bacterial cellulose with guided assembly-based biolithography (GAB) ACS Nano. 2015;9:206–219. doi: 10.1021/nn5036125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Scherner M, et al. In vivo application of tissue-engineered blood vessels of bacterial cellulose as small arterial substitutes: proof of concept? J Surg Res. 2014;189:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Klemm D, et al. Nanocelluloses: a new family of nature-based materials. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:5438–5466. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ogawa K, Maki Y. Cellulose as extracellular polysaccharide of hot spring sulfur-turf bacterial mat. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry. 2003;67:2652–2654. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Laus MC, et al. Role of cellulose fibrils and exopolysaccharides of Rhizobium leguminosarum in attachment to and infection of Vicia sativa root hairs. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:533–538. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smit G, et al. Molecular mechanisms of attachment of Rhizobium bacteria to plant roots. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2897–2903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Matthysse AG. Initial interactions of Agrobacterium tumefaciens with plant host cells. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1986;13:281–307. doi: 10.3109/10408418609108740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Balbontin R, et al. Mutualistic interaction between Salmonella enterica and Aspergillus niger and its effects on Zea mays colonization. Microb Biotechnol. 2014;7:589–600. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marsh AJ, et al. Sequence-based analysis of the bacterial and fungal compositions of multiple Kombucha (tea fungus) samples. Food microbiology. 2014;38:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brown AJ. On acetic ferment which forms cellulose. J Chem Soc Transactions (London) 1886;49:432–439. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamada Y, et al. Description of Komagataeibacter gen. nov., with proposals of new combinations (Acetobacteraceae) J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2012;58:397–404. doi: 10.2323/jgam.58.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nielsen L, et al. Cell-cell and cell-surface interactions mediated by cellulose and a novel exopolysaccharide contribute to Pseudomonas putida biofilm formation and fitness under water-limiting conditions. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1342–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zaets I, et al. Bacterial cellulose may provide the microbial-life biosignature in the rock records. Adv Space Res. 2014;53:828–835. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kubiak K, et al. Complete genome sequence of Gluconacetobacter xylinus E25 strain - Valuable and effective producer of bacterial nanocellulose. Journal of biotechnology. 2014;176C:18–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ogino H, et al. Complete genome sequence of NBRC 3288, a unique cellulose-nonproducing strain of Gluconacetobacter xylinus isolated from vinegar. Journal of bacteriology. 2011;193:6997–6998. doi: 10.1128/JB.06158-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Du XJ, et al. Genome sequence of Gluconacetobacter sp. strain SXCC-1, isolated from Chinese vinegar fermentation starter. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:3395–3396. doi: 10.1128/JB.05147-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Iyer PR, et al. Genome sequence of a cellulose-producing bacterium, Gluconacetobacter hansenii ATCC 23769. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192:4256–4257. doi: 10.1128/JB.00588-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Andres-Barrao C, et al. Genome sequences of the high-acetic acid-resistant bacteria Gluconacetobacter europaeus LMG 18890T and G. europaeus LMG 18494 (reference strains), G. europaeus 5P3, and Gluconacetobacter oboediens 174Bp2 (isolated from vinegar) Journal of bacteriology. 2011;193:2670–2671. doi: 10.1128/JB.00229-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dos Santos RA, et al. Draft genome sequence of Komagataeibacter rhaeticus strain AF1, a high producer of cellulose, isolated from Kombucha tea. Genome announcements. 2014;2:e00731–00714. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00731-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yamada Y. Transfer of Gluconacetobacter kakiaceti, Gluconacetobacter medellinensis and Gluconacetobacter maltaceti to the genus Komagataeibacter as Komagataeibacter kakiaceti comb. nov., Komagataeibacter medellinensis comb. nov. and Komagataeibacter maltaceti comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:1670–1672. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.054494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cleenwerck I, et al. Differentiation of species of the family Acetobacteraceae by AFLP DNA fingerprinting: Gluconacetobacter kombuchae is a later heterotypic synonym of Gluconacetobacter hansenii. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:1771–1786. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.005157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Marsh AJ, et al. Sequence-based analysis of the bacterial and fungal compositions of multiple kombucha (tea fungus) samples. Food Microbiol. 2014;38:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]