Abstract

Progressive human immunodeficiency viral (HIV) infection commonly leads to a constellation of cognitive, motor and behavioral impairments. These are collectively termed HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). While antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces HAND severity, it does not affect disease prevalence. Despite decades of research there remain no biomarkers for HAND and all potential co-morbid conditions must first be excluded for a diagnosis to be made. To this end, we now report that manganese (Mn2+)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) can reflect brain region specific HIV-1-induced neuropathology in chronically virus-infected NOD/scid-IL-2Rγcnull humanized mice. MEMRI diagnostics mirrors the abilities of Mn2+ to enter and accumulate in affected neurons during disease. T1 relaxivity and its weighted signal intensity are proportional to Mn2+ activities in neurons. In 16-week virus-infected humanized mice, altered MEMRI signal enhancement was easily observed in affected brain regions. These included, but were not limited to, the hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, globus pallidus, caudoputamen, substantia nigra and cerebellum. MEMRI signal was coordinated with levels of HIV-1 infection, neuroinflammation (astro- and micro- gliosis), and neuronal injury. MEMRI accurately demonstrates the complexities of HIV-1 associated neuropathology in rodents that reflects, in measure, the clinical manifestations of neuroAIDS as it is seen in a human host.

Keywords: Biomarkers, HIV-1 Neuropathology, Humanized mice, Manganese-enhanced MRI (MEMRI), Neuroinflammation

Introduction

HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) is a clinical disorder that reflects the cognitive, behavioral and motor dysfunctions associated with progressive viral infection [1]. HAND reflects a spectrum of clinical abnormalities that include asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) and HIV-associated dementia (HAD) [2]. Although antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly decreased the HAD incidence and prevalence, ANI and MND are seen in half of infected patients [3] and as such continues to be a significant quality of life complication of HIV/AIDS [4, 5]. Despite advances in the understanding HIV neuropathobiology, disease diagnosis is made by exclusion of co-morbid conditions such as drug abuse, neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders, opportunistic infections and malignancies [6]. Moreover, levels of viral replication and cognitive impairment are not always linked nor do they provide clear relationships between neuropathology and cognitive function [4]. It is possible that diagnostic clarity could be provided through imaging biomarkers.

In attempts to detail HIV-associated neuropathology, our laboratories pioneered the development of murine models of virus-associated brain disease [7]. Specifically, we show that humanized mice reconstituted with CD34+ human hematopoietic stem cells reflect the consequences of viral infection and consequent immune deterioration in its human host [8–11]. In this model, human progenitor cells are transplanted into genetically modified immunodeficient NOD/scid-IL-2Rγcnull (NSG) mice [12]. Such mice support persistent HIV-1 infection leading to behavioral and motor impairments paralleling neuronal and glial responses [13]. Our recent works demonstrated that brain imaging such as proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can uncover the neuropathological consequences of chronic HIV-1 infection in these mice [8, 13].

A significant advantage for manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) over other magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) modalities rests in the ability to directly map voltage-gated calcium channel activity through manganese ions (Mn2+) neuronal accumulation. As Mn2+ is a calcium (Ca2+) analogue, it can enter neurons by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels[14] and can be moved anterograde by axonal transport and microtubule assembly [15, 16]. Mn2+ is an excellent T1 shortening contrast agent affording relatively high spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio within reasonable scanning time [17, 18]. Administration of Mn2+ generates enhanced signal intensity on T1-wt images. The signal enhancement is associated with neuronal activities. MEMRI can assess neuronal well-being for anatomical, integrative, functional and axonal transport activities of nerve cells and their connections [14, 19]. Herein, we demonstrate that MEMRI facilitates precise noninvasive high spatial resolution (100 µm3 isotropic) determinations of brain regions of HIV-1 incited neuroinflammation and neuronal injury in NOD/scid-IL-2Rγcnull humanized mice. Correlations between immunocytochemical measures of brain disease and MEMRI signal enhancement are operative.

Materials and Methods

Murine neuroAIDS model

NOD/scid-IL-2Rγcnull (NSG) mice were bred under specific-pathogen-free conditions in accordance with the ethical guidelines at the University of Nebraska Medical center (UNMC), Omaha, Nebraska. Human cord blood obtained with parental written informed consent from healthy full-term newborns (Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, UNMC) was utilized for CD34+ cells isolation using immune-magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's instructions (CD34+ selection kit; Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA). Numbers and purity of human CD34+ cells were evaluated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Cells were either frozen or immediately transplanted into newborn mice at 105/mouse intrahepatically (i.h.) in 20 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using a 30-gauge needle. Newborn mice received human cells from single donors. On the day of birth, newborn mice were irradiated at 1 Gy using a C9 cobalt 60 source (Picker Corporation, Cleveland, OH). Starting from 22 weeks after reconstitution, HIV-1 virus was intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected at 104 TCID50 into mice. Humanized mice without infection served as controls. Number of human cells and the level of engraftment were analyzed by flow cytometry. In the study, all protocols related to animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), UNMC University and met the requirements of the UNMC University ethical guidelines, which are set forth by the National Institutes of Health.

Viral load

The automated COBAS Amplicor System V1.5 (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) was used to measure the peripheral level of viral RNA copies/ml. Mouse plasma (20 µl) was used to dilute with 480 µl of sterile normal human plasma for the assay. The baseline detection of assay after dilution is 1250 viral RNA copies/ml.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood leukocytes, spleen and bone marrow cell suspensions were examined for anti-human-CD45, CD3, CD4 and CD8 markers. Flow cytometry for peripheral blood leukocytes was done every other week from the point of infection. At the end of study, flow cytometry was done for spleen and bone marrow as well. Mouse peripheral blood samples were collected from submandibular vein (cheek bleed) by using lancets (MEDIpoint, Inc., Mineola, NY) in EDTA coated tubes. Antibodies and isotype controls (BD Phar-Mingen, San Diego, CA) were used to stain cells. Staining was analyzed by using FACSDiva (BD Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA). Percentages of total number of gated lymphocytes were expressed as results.

Immunohistology

At 16 weeks, mice were euthanized immediately after imaging and brains were collected. Brain tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin. Five µm thick brain tissue sections were labeled with mouse monoclonal antibodies for HLA-DQ/DP/DR (1:100, Dako, Carpinteria, CA), HIV-1 p24 (1:10, Dako), c-Fos (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and rabbit polyclonal antibodies for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (1:1000, Dako), ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule -1 (Iba-1) (1:500; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA), Caspase3 (1:10, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). The polymer-based HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit Dako EnVision systems were used as secondary detection reagents, and 3,3’-diaminbenzidine (DAB, Dako) was used as a chromogen. All paraffin-embedded sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Deletion of primary antibodies served as controls. Images were captured with a 100×, 40× and 20× objectives using Nuance EX multispectral imaging system fixed to a Nikon Eclipse E800 (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY).

For immunofluorescence labeling, brain sections were treated with the paired combination of primary antibodies mouse anti-synaptophysin (SYN) (1:1000, EMD Millipore), and rabbit anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) (1:500, EMD Millipore), mouse antineurofilament (NFs) (1:200, Dako) and rabbit anti-GFAP (1:1000, Dako); additionally, brain sections were treated alone with rabbit anti-Iba-1(1:500). Primary antibodies were labeled with secondary anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to the fluorescent probes Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594, and nuclei were labeled with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Slides were cover-slipped with ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Slides were stored at −20 °C after drying for 24 hours at room temperature. Images were captured at wavelengths encompassing the emission spectra of the probes, with a 40× objective by Nuance EX multispectral imaging system fixed to a Nikon Eclipse E800 and image analysis software (Caliper Life sciences, Inc., a Perkin Elmer Company, Hopkinton, MA) was used for quantification of SYN, MAP2, NF and GFAP expression. Area-weighted average fluorescence intensity was calculated in the region of interest (ROI) by dividing the total signal intensity, for each partitioned area, by area (µm2) as intensity/µm2. Images were also captured with LSM 710 microscope using a 40X oil lens (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC, NY, USA). Expression of cFos was scored (out of 10) by two investigators using 20× objective in blinded manner. Findings were compared to animals that were not manipulated (score 0). Student’s t-tests were performed to compare immunohistological results of the HIV-1 infected animals with controls.

MEMRI

MnCl2·4H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added to 0.9% w/v NaCl (Hospira, Lake forest, IL) to make 50 mM MnCl2 solution. MnCl2 solution was administrated i.p. with the dose of 60 mg/kg consecutively four times at 24 hour intervals before MRI. After the injection, the mouse was observed daily to detect the side effects of MnCl2.

MRI data were acquired 24 hours after the last MnCl2 administration on Bruker Bioscan 7 Tesla/21 cm small animal scanner (Bruker, Billerica, MA) operating Paravision 5.1 with a 72 mm volume resonator and a 4-channel phased array coil. Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane in 100% oxygen and maintained 40–80 breaths/minute. Mice were scanned using T1 mapping sequence (fast spin echo with variable repetition time (TR) from 0.4 s to 10 s, 12 slices, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, in-plane resolution = 0.1 × 0.1 mm2) and T1-wt MRI (FLASH, TR = 20 ms, flip angle = 20°, 3D isotropic resolution = 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm3). After MRI, the mice were euthanized and tissues were removed for immunohistological study. The same scan was also performed before the MnCl2 administration, and the acquired image was used as baseline data for the calculation of signal enhancement.

MRI data pre-processing

To reduce the influence of the inhomogeneous signal reception on the T1-wt images by the phased array surface coil, N3 field inhomogeneity correction [20] was first performed on each image using MIPAV (CIT, NIH). The brain volumes in the T1-wt images were extracted using an in-house Matlab program [21] based on the level sets method. The brain images were then registered to a MEMRI-based NSG mouse brain atlas developed in our laboratories using affine transformation first, and then nonlinear transformation (DiffeoMap, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD).

To calculate Mn2+ induced T1-wt signal enhancement, the MRI system variations between the baselines and post MnCl2 injection scans need to be minimized. This is achieved by calibrating the baseline and post Mn2+ injection T1-wt images using T1 values. A detailed description of the MEMRI enhancement calculation and T1-wt image calibration are included in the Online Resource 1. The T1 maps were first generated using an in-house Interactive Data Language (IDL) version 8.2 (Exelis Visual Information Solutions, Boulder, Colorado) program from the data acquired by T1 mapping sequence. ROIs were then placed on relatively uniform tissue regions including frontal cortex and caudate on T1 maps and T1-wt images. The baseline and post Mn2+ injection longitudinal relaxivity (R1blROI and R1MnROI) and T1-wt signal intensity (SblROI and SMnROI) in the ROIs were measured. The calibration factor was calculated as C = (SMnROI/SblROI) × (R1blROI/R1MnROI). The baseline T1-wt image (Sbl) was then calibrated using the calibration factor C : SblC = Sbl × C.

MEMRI enhancement analysis

The Mn2+ induced T1-wt signal enhancement was calculated by: (SMn – SblC) / SblC. A pixel-by-pixel comparison was first performed between the HIV-1 infected mice and the control group using Student’s t-test, followed by a brain region specific analysis. Using the MEMRI-based brain atlas, the T1-wt signal enhancement on 41 brain regions/sub-regions was calculated. The student’s t-test was performed to exam the significance of enhancement change in each HIV-1 infected brain region compared to the control group.

The association between MRI signal changes, plasma viral load, T-cells and immunohistological results in HIV mice was examined using Pearson product-moment correlation. The association between enhancement and quantified GFAP, Iba-1, MAP2, NF and SYN staining was studied on the CA1, CA3 and DG brain regions. Time course of infection that included measures of the plasma viral load at the time of animal sacrifice (16 WPI), its rate of change (slope) over time, and change in maximum and end time viral levels were measured. These parameters tested over time were correlated with MRI signal enhancements. The T-cell parameters that were measured over time included blood, spleen and bone marrow CD4 and CD8 positive T cell numbers.

Brain structure volumetric analysis

In the MRI data pre-processing, the brain images were registered to the MEMRI-based brain atlas. The 41 brain regions were identified on each brain image. The brain images were transferred back to their original spaces employing the inverse of the transformation matrices calculated for registration. The volumes of the regions were calculated in the original spaces. Student’s t-tests were performed to compare the volumes of the HIV-1 infected animals with controls.

Detection of Mn2+ toxicity

Animals were observed daily after each i.p. MnCl2 injection and 24 hours after the injection. If tremor or convulsion (the signs of manganese overdose) persisted longer than 3 minutes or lethargy observed at 24 hours, mice were euthanized.

Results

HIV-1 Infection of humanized mice

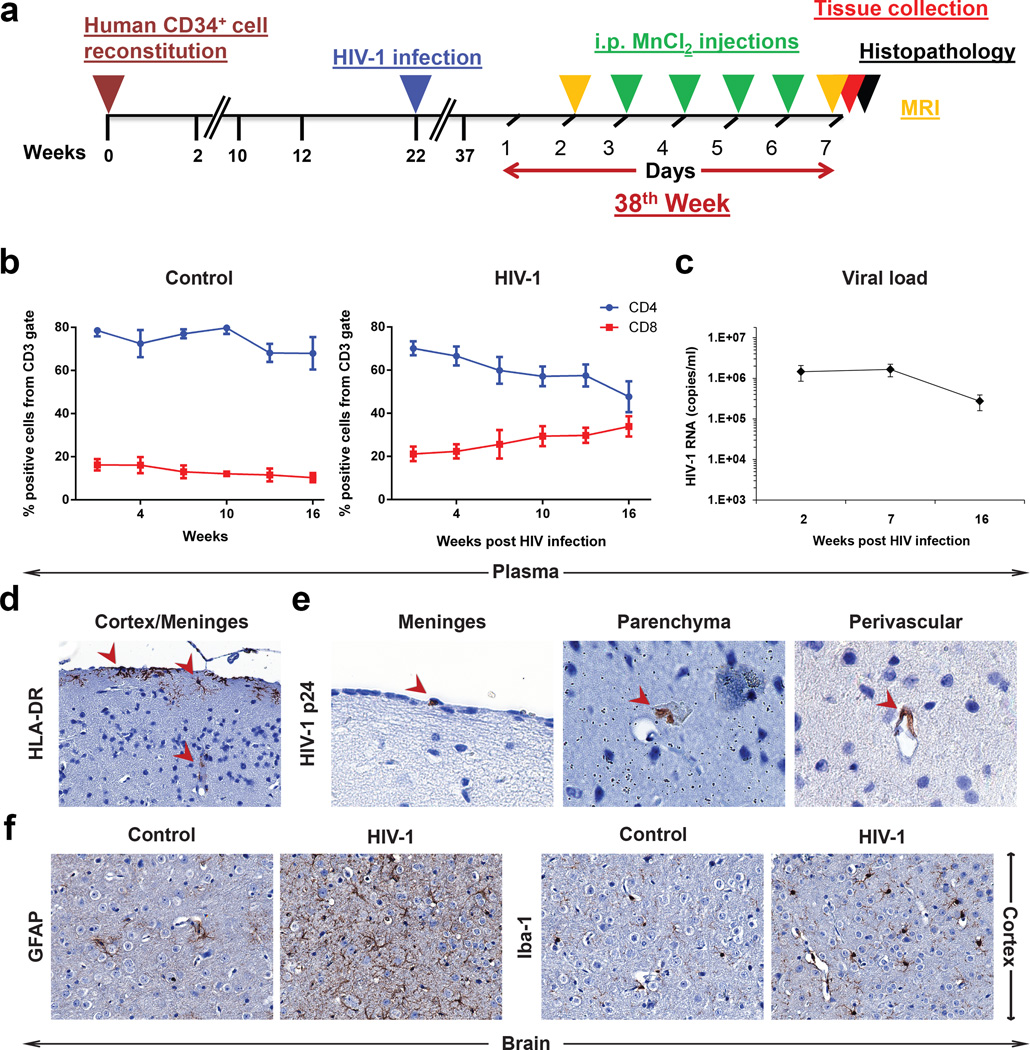

Humanized mice (n = 8) were infected with the HIV-1ADA at 22 weeks of age (Fig. 1a). Viral and immune parameters were assessed then compared against controls (uninfected humanized mice, n = 7). Flow cytometry was performed at 2, 4, 7, 10, 13 and 16 weeks post infection (WPI) to determine reconstitution of peripheral human immune cells (CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8). The temporal changes of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in infected humanized mice are shown in Fig. 1b. The steady CD4+ T cells decline and concomitant increases in CD8+ T cells were readily seen in HIV-1 infected mice. Control uninfected animals showed no changes in T cell numbers throughout the study period (Fig. 1b). Plasma viral RNA copies/ml (viral load, VL) measures were performed at 2, 7, 16 WPI (Fig. 1c). These VL values peaked at the 2nd week after HIV-1 infection and were sustained throughout the experimental observation period.

Figure 1.

(a) The time course of human CD34+ cell reconstitution, HIV-1 infection, MRI, MnCl2 injections and histopathology. (b) Results from flow cytometric analyses of human CD4+ and CD8+ cells in peripheral blood of control mice (left) and infected mice (right). (c) Average HIV-1 RNAs (copies/ml) in peripheral blood of infected mice (n = 8). (d and e) Infiltration of human activated cells detected by HLA-DR (indicated by arrows, left, 20×) and HIV-1+ cells (detected by p24 antigen) in meninges, parenchyma and perivascular spaces (positive cells indicated by arrows, right, 100×) into the brain of infected mice at 16 WPI. (f) Brain sections of control and infected mice stained by GFAP for astrocyte (left, 40×) and by Iba-1 for microglial (right, 40×). Activated glial cell morphologies were seen in infected animals. Data are expressed as mean SEM in (B) and (C)

Leukocyte brain infiltration

Brain infiltration of human cells including those HIV-1 infected were assessed by immunohistochemical assays. At 16 WPI, brain sections at 5 µm thickness were stained for human HLA-DR and HIV-1p24. Human HLA-DR+ cells infiltrated the brains of infected and control mice were seen in the meninges and perivascular spaces (Fig. 1d). Few HIV-1p24+ human cells were observed in these regions of infected mice (Fig. 1e). Glial responses were assessed by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, astrocyte) and ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule-1 (Iba-1, microglia) staining. Cortical areas with hypertrophic astrocytes and morphological features of activated microglia were readily observed (Fig. 1f). Such activated glial morphologies were not seen in control animals.

MEMRI

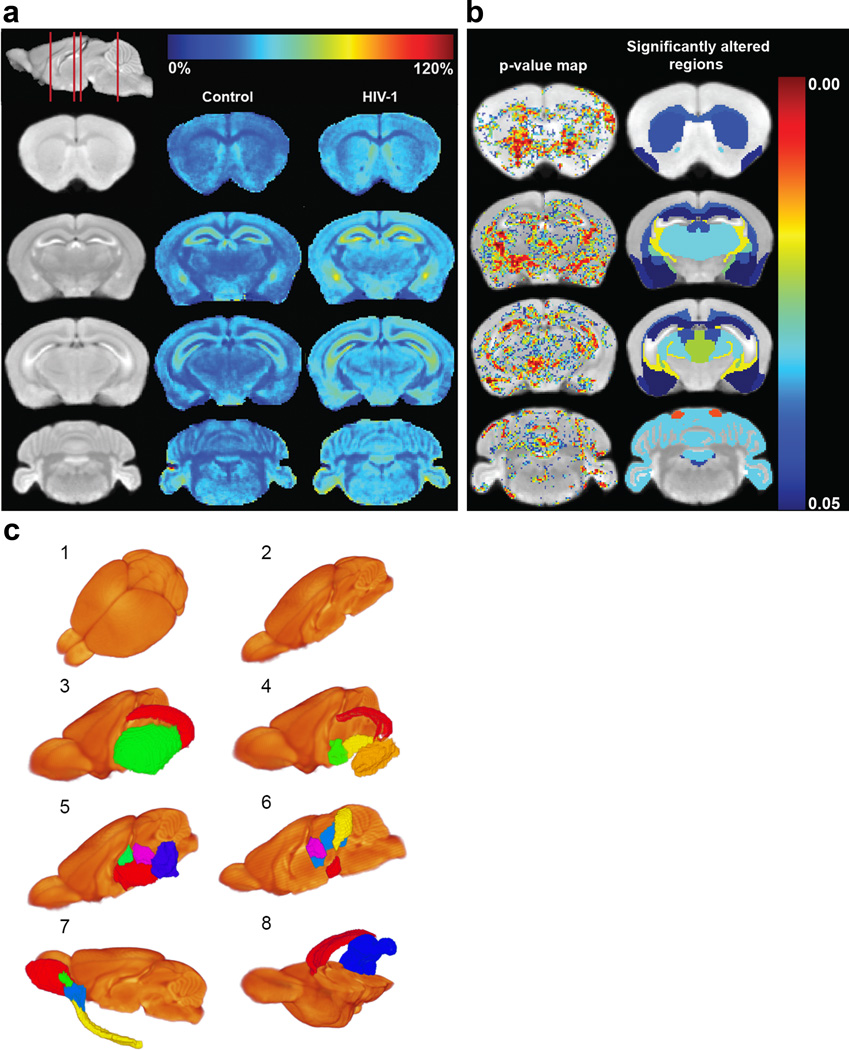

To track neuropathology induced by continuous HIV-1 infection, MEMRI was performed at WPI (Fig. 1a). The averaged MEMRI image of the control mice is shown on coronal brain slices as an anatomical reference in the left column of Figure 2a. Positions of the coronal slices are depicted using a sagittal slice (top of the left column). Standard tissue signal enhancement induced by Mn2+ was readily seen within the olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum [19]. The color-coded average enhancement maps of the control and HIV-1 infected mouse brains are illustrated in the second and third columns of Figure 2a, respectively. The enhancement represented the signal change induced by Mn2+ normalized to the MRI signal of pre-Mn2+ administration. MEMRI enhancement changes were observed throughout the brain in HIV-1 infected animals compared to controls (Fig. 2a). Statistically significant increases in the MEMRI enhancement are shown by pixels with p < 0.05 (the first column in Fig. 2b). These p values are color-coded and overlaid on the averaged MEMRI slices. Using the MEMRI-based mouse brain atlas, 41 brain regions/sub-regions were identified for each humanized mouse. A video demonstrating the brain atlas in three-dimensional space is included in Online Resource 2, and a list of regions on the brain atlas can be found in Online Resource 3. The MEMRI enhancement was compared between each brain region of control and HIV-1 infected mouse. The regions with p values less than 0.05 from such comparisons are shown in the second column in Figure 2b and illustrated with identical color-coding as in the first column. The brain regions with significantly increased signal enhancement (p < 0.05) are also included within Table 1. Three-dimensional images of brain regions with significant enhancement increase are illustrated in Figure 2c. Morphological and volumetric changes were assessed in virus-infected animals by the MEMRI mouse brain atlas. Whole brain and regional volumes in the HIV-1 infected mice were comparable to control animals (data not shown). The toxicity of Mn2+ was considered. Mice were observed daily after i.p. MnCl2 injections. This included chemical injection linked tremor and lethargy, the clinical signs of Mn2+ overdose. No Mn2+ induced toxic signs and symptoms were observed during the study.

Figure 2.

Comparison of MEMRI enhancement between HIV-1 infected animals and controls. (a) MEMRI enhancement maps. The first column (from left) shows coronal slices of the averaged MEMRI of control mice as an anatomical reference. The sagittal slice (upper left) shows respective coronal positions (red lines). The second column shows the average enhancement in control mice on the coronal slices. The third column represents the average enhancement of HIV-1 infected mice. The color bar for the enhancement maps is at the top of the figure. Dark blue color (0%) means no change in enhancement from Mn2+ compared to pre-injection signal intensity. Dark red color represents 120% signal increase compared to pre-injection. Increase in MEMRI enhancement can be seen throughout the brain of infected animals than controls. (b) Statistical comparison of MEMRI enhancement between control and HIV-1 infected animals. The left column shows the pixels with significant enhancement difference (p < 0.05) overlaid onto the averaged brain image. The color bar of p values is at the right. Dark blue color represents p = 0.05 and dark red color represents the value of 0.00. The right column shows significantly altered brain regions of infected mice using the same color scale. (c) Brain regions with significant enhancement changes demonstrated in 3-D. (1) Averaged brain image. (2) Right hemisphere of the averaged brain. Internal brain regions can be seen on the middle of sagittal section. (1 and 2) are to provide anatomical references for the demonstration of regions with significant enhancement changes. (3) Sub-cortical regions including CA1_CA3_SUB (red) and CP (green). (4) Sub-cortical regions including DG-mo (red), AMY (orange), PALc (green), and GP (yellow). (5) Brain stem regions including TH (red), EPI (green), SN (blue) and PRT (purple). (6) PAG (blue), IC (yellow), SN (red) and PRT (purple). (7) Olfactory regions including MOB (red), AOB (green), AON (blue) and PIR (yellow). (8) cc (red) and CBXmo (blue). The full names of the brain regions are included in Table 1

Table 1.

Brain regions that showed significant signal enhancement

| Brain regions | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-cortical region | CA1_CA2_SUB | 0.047 |

| DG-mo | 0.046 | |

| CP | 0.039 | |

| AMY | 0.048 | |

| GP | 0.028 | |

| PALc | 0.047 | |

| Brain stem region | TH | 0.03 |

| EPI | 0.043 | |

| P | 0.044 | |

| PAG | 0.022 | |

| IC | 0.01 | |

| SN | 0.041 | |

| RMB | 0.033 | |

| PRT | 0.043 | |

| Olfactory region | MOBgl | 0.021 |

| AOB | 0.012 | |

| PIR | 0.046 | |

| AON | 0.036 | |

| Cerebellar region | CBXmo | 0.031 |

| Fiber tracts | cc | 0.037 |

CA1_CA2_SUB: Field CA1 + Field CA2 + Subiculum of Hippocampus Formation, DG-mo: Dentate gyrus_molecular layer, CP: Caudoputamen, AMY: Amygdala, GP: Globus pallidus, PALc: Pallidum caudal region, TH: Thalamus, EPI: Epithalamus, P: Pons, PAG: Periaqueductal gray, IC: Inferior colliculus, SN: Substantia nigra, RMB: Rest of midbrain, PRT: Pretectal region, MOBgl: Main olfactory bulb glomerular layer, AOB: Accessory olfactory bulb, PIR: Olfactory piriform area, AON: Anterior olfactory nucleus, CBXmo: Cerebellar cortex molecular layer, cc: corpus callosum, (p < 0.05) (p: t test p value)

Immunohistology

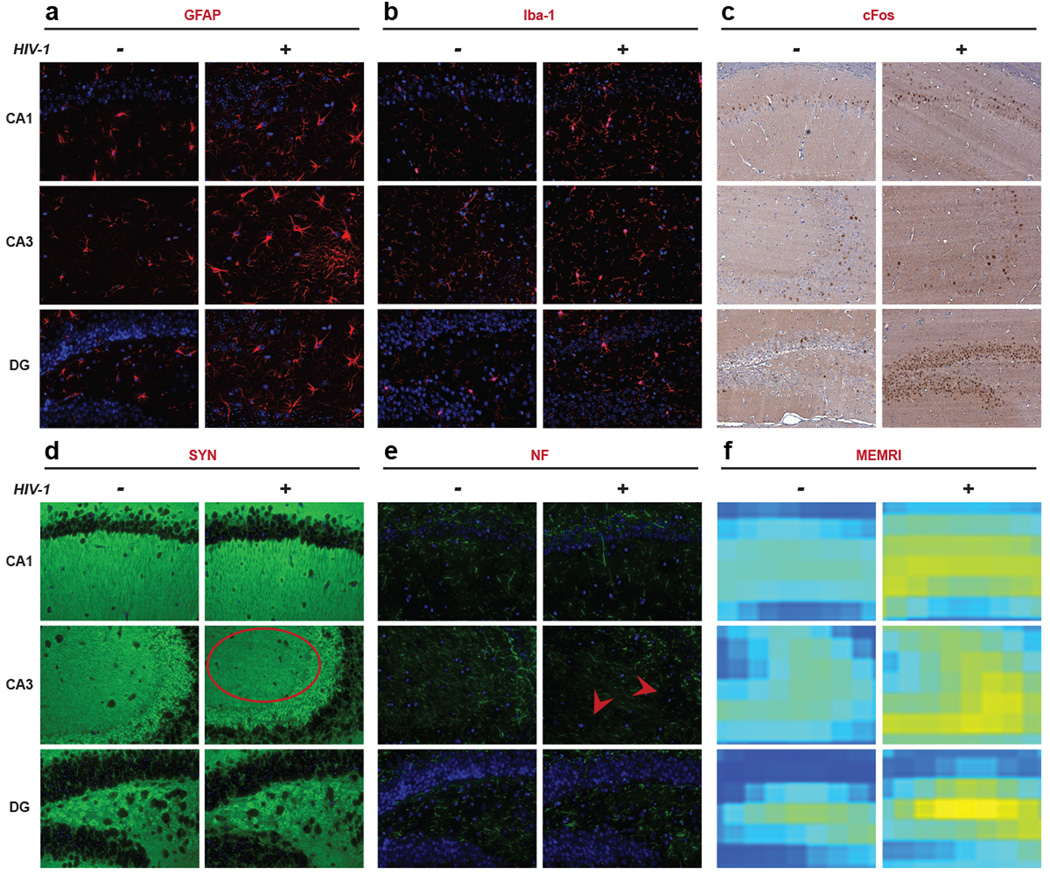

Immunohistochemistry was subsequently performed on CA1, CA3 and the dentate gyrus (DG) regions of the hippocampus at study termination, 16 WPI (Fig. 1a). Brain sections were stained for GFAP, Iba-1, cFos (neuronal activation), synaptophysin (SYN, synaptic vesicle protein), and neurofilament (NF, neuronal cytoskeleton protein). Fluorescence intensity for these antigens was expressed as intensity/µm2. Activated morphologies were observed as defined by increased cell body size and process formations for both astrocytes and microglia in virus-infected animals (Fig. 3a and 3b). The presence of activated astrocytes and microglia are known to be linked to virus-induced inflammation [22, 23]. Neuronal activation (cFos expression) was substantially higher in brain regions with gliosis and specifically in the hippocampus; indicating increased neuronal excitation during inflammation (Fig. 3c). Irregularly shaped and decreased SYN expression was seen in the CA3 region of infected animals and reflected synaptic injury (Fig. 3d). Reduction in NF fibers was also observed at CA3 region in infected animals (Fig. 3e). NF and SYN expression demonstrates neuronal injury after glial inflammation. Co-localized MEMRI enhancement in infected animals was compared to controls and confirmed the sensitivity of the MEMRI in reflecting glial and neuronal histochemical and morphological changes (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3.

Immunohistology of the hippocampus sub-regions including CA1, CA3 and DG (40×). Representative brain sections of control and HIV-1 infected mice stained for GFAP (astrocyte), Iba-1 (microglia), cFos (neuronal activation), SYN (synaptic vesicle protein), NF (neuronal cytoskeleton protein) and co-localized MEMRI slices are presented. (a, b and c) Increase in GFAP, Iba-1 and cFos expression was observed in infected animals compared to controls in all three regions of hippocampus. (d and e) In CA3 region, SYN and NF expression was decreased (indicated by an oval and arrows, respectively) of infected animals compare to controls, but not in CA1 or DG. (f) Altered in MEMRI enhancement in co-localized brain slices was observed in infected animals

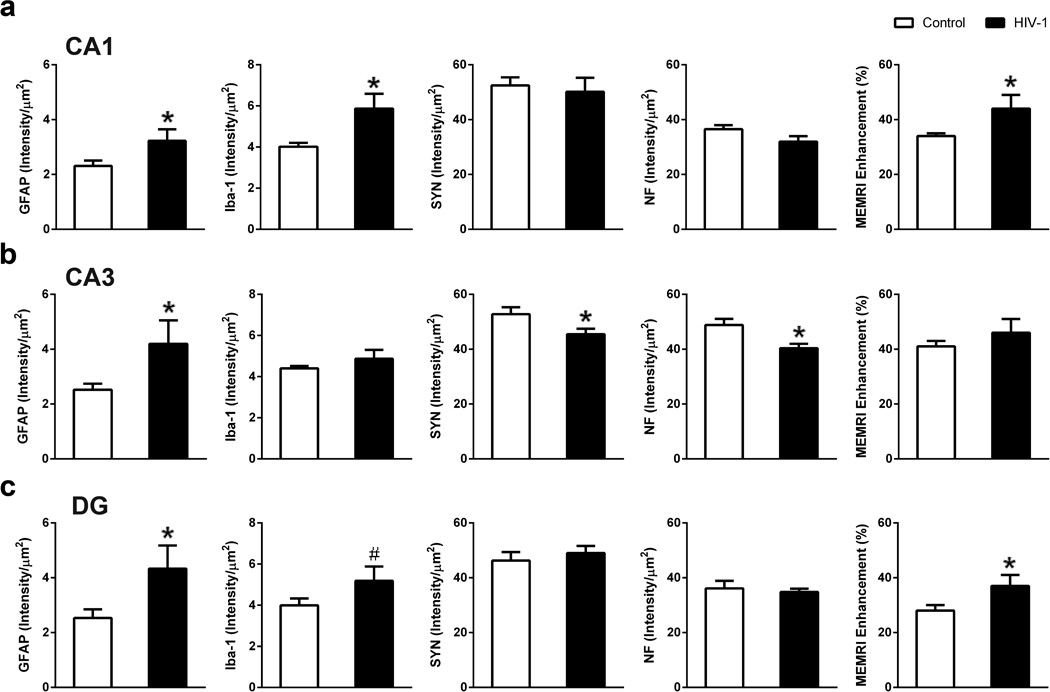

Quantitative immunohistochemistry was used to compare neuropathology between control and HIV-1 infected mice and its association with MEMRI regional enhancements. In CA1 region, GFAP and Iba-1 expression were significantly higher in infected animals than controls (GFAP, p = 0.041; Iba-1, p = 0.018); whereas, SYN and NF expression were not different amongst the groups (Fig. 4a). Gliosis with no evidence of neuronal injury in CA1 paralleled significant MEMRI signal enhancement increase in infected animals compared to controls (p = 0.047) (Fig. 4a). In the CA3 region, GFAP expression was higher (p = 0.038), and SYN and NF expression lower (SYN, p = 0.027; NF, p = 0.005); whereas, Iba-1 signals were not changed by viral infection (Fig 4b). With a combination of astrocyte responses and neuronal injury, MEMRI signal remained similar between infected and control animals (Fig. 4b). GFAP expression was higher (GFAP, p = 0.042) and Iba-1 increased but not significantly (Iba-1, p = 0.083) in the DG region of infected animals; whereas SYN and NF signals were not changed (Fig. 4c). MEMRI enhancement in this region was increased in infected animals (p = 0.045) (Fig. 4c). The quantitative analyses taken together, demonstrate that activated glia and neurons (increased cFos staining) during inflammation induced the increase in MEMRI signal in the CA1 and DG brain regions. However, the enhancement increase was offset by neuronal injury (reduced SYN and NF) in the CA3 brain region. Microtubule associated protein (MAP2) staining was not changed in the infected animals. Evidence for neuronal apoptosis determined by anti-caspase3 staining was not observed in infected mice (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Association of immunohistology with MEMRI. (a) Quantitative analysis showed significant increase in GFAP, Iba-1, and MEMRI enhancement on CA1 region of HIV-1 infected animals compared to controls. (b) CA3 region showed significantly increased GFAP, significantly decreased SYN as well as NF, and no change in MEMRI signal in infected animals compared to controls. (c) DG region showed significantly increased GFAP, a trend of increased Iba-1, and significantly increased MEMRI enhancement in infected animals compared to controls. Data are expressed as mean SEM. (*: p < 0.05, #: p < 0.1)

We next investigated if glial activation and MEMRI signal enhancements were correlated one with the other. In the CA1 and DG, correlations between GFAP expression and MEMRI signal increase were seen (CA1, r = 0.86, p = 0.007; DG, r = 0.92, p = 0.001). Linkages between gliosis and MEMRI enhancement demonstrated that Mn2+ uptake and accumulation increases in neurons affected by inflammation. This was associated with astrocyte responses and the MEMRI signals [24]. Next we measured relationships between the degree of brain injuries and VL in blood. The average brain MEMRI enhancement alteration was linked, in measure, to the peripheral VL difference of at 16 weeks and maximum values (defined as viral load dynamics; r = 0.714, p = 0.071). This result suggested that the greater the viral load drop during the course of infection, the smaller the MEMRI enhancement change. MEMRI enhancement was not affected by numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

Discussion

Humanized mouse model (NSG/CD34+) of HIV/AIDS can, in part, mirror human HIV-1 associated neuropathology [8, 9, 13] and was used successfully to test ART efficacy [25]. Peripheral VL and human CD4+ T-cell decline are hallmarks of HIV-1 infection in humans which are reflected in these humanized mice. Moreover, a metabolic encephalopathy caused by viral infection resulting in micro- and astro- gliosis, myelin pallor, excitotoxicity and neuronal injury is also seen in both humans and infected mice [8, 9, 13, 22]. Such spectrums of pathologies make the humanized mice a relevant model for study. In the present study, altered MEMRI brain signal is seen in HIV-1 infected mice that serve to assess the complexities of neuropathology that underlie HAND’s clinical manifestations. Although, MEMRI was used previously to study a range of neurodegenerative disease models [26–29], this is the first report of its use to study effect of HIV-1 on humanized mice brain function and anatomy with improved analytical method.

MEMRI enhancement for HIV-1 infection is linked to reactive astrocytes and activated neurons. The cellular basis of the enhancement change was investigated in a previous study and interpreted as elevated neuronal Mn2+ uptake and accumulation stimulated by astrocyte activation [24]. The associations between MEMRI signal with reactive astrocytes and neuronal responses was previously observed [24, 29, 30]. We previously showed that activated glia do not accumulate excessive Mn2+ but stimulate neuronal Mn2+ uptake [24]. Thus, MEMRI can be used to monitor virus-associated neuronal excitotoxicity that occurs as a consequence of neuroinflammation. In the CA3 region, both inflammation and neuronal injury (synaptic and axonal injury) were operative in the infected animals. This is consistent with the fact that neuronal damage caused by HIV-1 infection begins with synaptic damage, compromised dendrite arbor, then neuronal death occurs as a consequence of persistent infection and immune deterioration [31]. Interestingly, in CA3 region, we did not observed MEMRI signal increase as in CA1 and DG. Indeed, damaged neurons likely influence reduction in neuronal Mn2+ accumulation. The voxel size of MEMRI was 100 µm3, which contains a large number of cells. The MEMRI enhancement of each voxel resulted from the combining effects of activated and injured neurons. Simply, the MEMRI signal enhancement induced by activated neurons was likely offset by signal decrease in injured cells. Increasing spatial resolution can partially solve the problem as excited and injured neurons may be differentiated. Additionally, performing MEMRI and immunohistological analysis at multiple time points after the infection may also establish accurate associations between signal enhancements and neuronal injury.

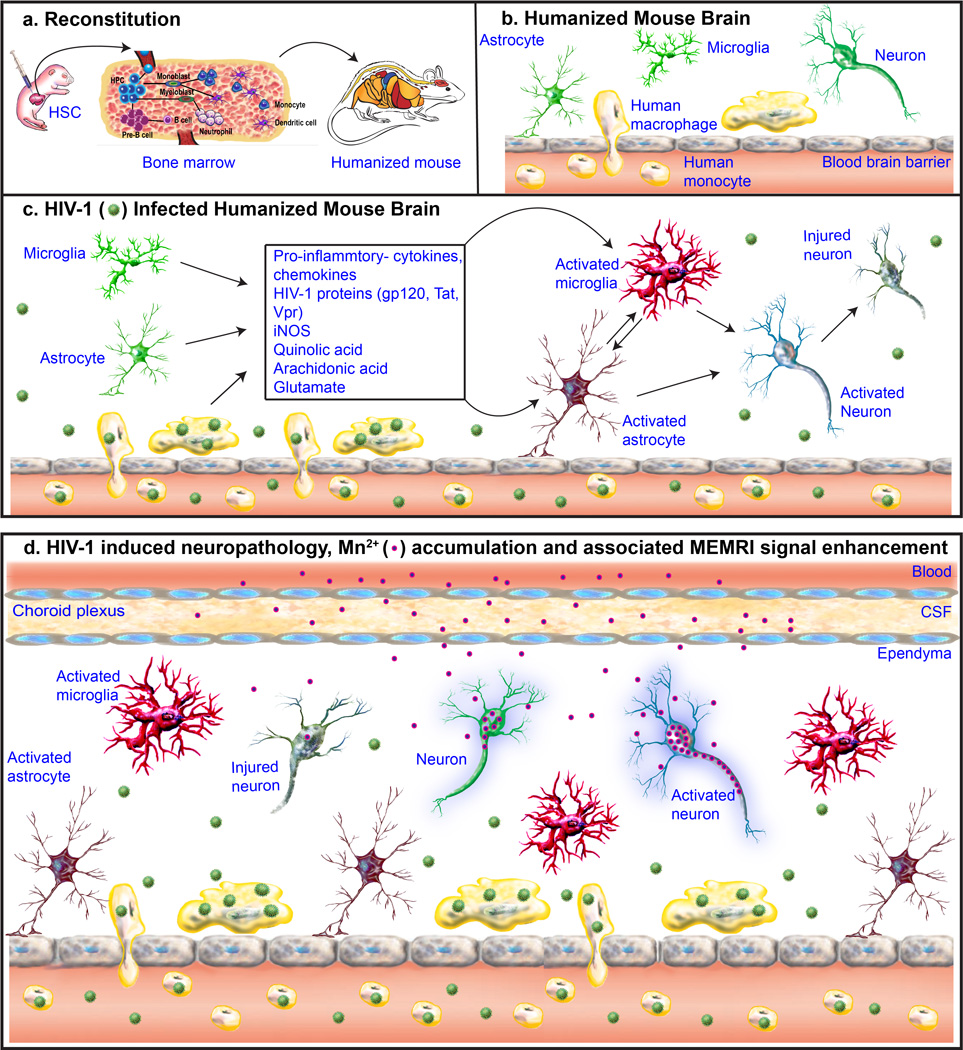

The cellular mechanism underlying MEMRI enhancement is summarized in Figure 5. Humanized mice permanently carry human blood cells, and these populate brain primarily at meninges and perivascular spaces. After HIV-1 infection, infected human monocyte-macrophages carry HIV-1 into the brain and release pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, viral proteins. This leads to activation of murine glia followed by neuronal excitotoxicity and injury, which in turn reflects the brain injuries seen as a consequence of chronic HIV-1 infection. Systemically administrated Mn2+ enters the brain through choroid plexus. As a Ca2+ analog, it enters neurons through voltage gated Ca2+ channels and is transported anterogradely by microtubule assembly. Once Mn2+ is released, it is taken up by post-synaptic neurons. Reactive astrocytes that arise as a consequence of HIV-1 induced neuroinflammation first cause elevated neuronal Mn2+ uptake resulting in increased MEMRI signal enhancement. Neuroinflammation then results in neuronal injury with consequent suppressed MEMRI signal.

Figure 5.

The mechanism of MEMRI in the detection of neuropathology in HIV-1 infected humanized mice. (a) Human immune system reconstitution (humanization) in NSG mouse. Human CD34+ stem cells (HSC) isolated from umbilical cord blood were injected intrahepatically into one day old irradiated pups. The injected HSC reach mouse lymphoid organs including bone marrow and develop into broad range of cell lineages. A mature human immune system develops in the NOD/scid-IL-2Rγcnull (NSG) mice. (b) Humanized mouse brain. Human cells (macrophages, yellow color) are majorly observed at meninges and perivascular spaces in humanized mouse brain. Mouse cells (resting glia and neurons) are showed in green colors. (c) HIV-1 infected humanized mouse brain. Infected human macrophages carry HIV-1 (green) into the brain and release pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines viral proteins, that leads to activated glia (red) followed by neuronal excitation (blue) and injury (gray). (d) HIV-1 induced neuropathology, Mn2+ accumulation and associated MEMRI signal enhancement. Mn2+ (blue and pink circle) enters brain through choroid plexus. Being Ca2+ analog, it enters neurons through voltage gated Ca2+ channels. Mn2+ is transported anterogradely by microtubule assembly. Once Mn2+ is released, it is taken up by post-synaptic neurons. Mn2+ accumulation increases in activated neurons during inflammation resulting in MEMRI signal enhancement increase (stronger purple outer glow compared to control). Whereas, Mn2+ uptake and transportation are reduced in injured neurons and thus MEMRI signal is suppressed

In our parallel works, behavioral tests were used to show memory loss and cognitive dysfunction in these infected mice [13]. As the hippocampus plays an important role in memory and cognition, the glial activation and neuronal injury in this brain region detected in this study may contribute to such behavioral abnormalities. Aside from the hippocampus, the brain regions that show MEMRI signal enhancement following HIV-1 infection include sub-regions of the olfactory system, sub-cortical, brain stem and cerebellar regions. These findings suggest that infected mice can suffer motor and autonomic nervous system dysfunction because of cerebellar and brain stem damage. As different parts of the brain have variable vulnerabilities to HIV-1 infection [32, 33], the current study provides a unique opportunity for unbiased mapping of region specific neuropathology.

The MEMRI results are supported by the DTI measures in our parallel study [13]. This study showed altered DTI parameters on hippocampal regions in HIV infected humanized mice, and association between the DTI parameters and quantitative histology. In infected human and nonhuman primates, abnormal DTI were found in the frontal and parietal white matter, putamen, and corpus callosum indicating neuroinflammation and axonal/myelin injury [34, 35]. In parallel, inflammation metabolic abnormalities were detected by MRS in the basal ganglia, cerebrum, caudate, thalamus, and hippocampus [34–36]. We acknowledge that a direct comparison of the brain imaging findings in humans and nonhuman primates with mice is difficult due to differences in anatomy, physiology, and neurochemistry. Our results are consistent with these human and non-human primate studies.

It is likely that abnormalities seen in these animals were not primarily a result of active viral replication in nervous system, but largely a consequence of replication in blood and peripheral lymphoid organs. Until now, studies have shown that peripheral blood nadir CD4+ T-cells count and viral DNA are systemic predictors of HIV-1 induced neurocognitive disorders [3, 37, 38]. However, we did see a trend towards correlation between MEMRI signal enhancement alteration and a plasma viral load measure, which is the difference between the maximum value and at 16 WPI. A parallel study found that viral levels correlated with cortical lactate [13]. The same study also found the correlation or the trend of correlation between cortical and dentate gyrus DTI parameters and viral load. Their study along with ours suggested that peripheral viral load might be associated with the neuropathology reflected by imaging in HIV-1 infected humanized mice. Such a sensitivity of the brain to peripheral events in these animals indicates a dynamic pathogenic process; where HIV-1 infected blood cells enter into the brain and cause disease [39].

We now demonstrate that MEMRI is a sensitive biomarker of HIV-1-induced neuropathology. However, when inflammation and neuronal impairment occur simultaneously, both increase and decrease in MEMRI signal can be observed. In order to improve the specificity of imaging on neuropathology, it is reasonable to combine MEMRI with other imaging modalities. For example, another study showed that the cerebral cortex is a primary region of damage in infected mice as demonstrated by MRS and DTI [13]. Combining MEMRI with MRS and DTI can positively determine neuroinflammation (increased MEMRI enhancement and increase in myoinositol), and may help to detect neuronal impairment (reduced MEMRI enhancement, loss of N-acetylaspartate and creatine, reduced diffusivity, and fractional anisotropy). This package of imaging modalities will greatly enhance our ability for non-invasive assessment of HIV-1 induced neuropathology. In addition to assessment of neuronal Mn2+ uptake, MEMRI can provide precise anatomical details. To this end, we applied a MEMRI-based NSG mouse brain atlas to assess brain morphology to reveal abnormalities associated with HIV-1 infection in an animal study. As we expected, we did not find changes in total brain and substructural volumes with altered MEMRI enhancement. This suggests that neuronal death is limited in infected animals. MEMRI successfully provided both insights into neuronal function and the measurements of brain anatomy.

The toxicity of Mn2+ was minimized by a carefully designed MnCl2 administration. We have used a fractionated administration scheme first proposed by [40]. In this scheme, MnCl2 solution was injected daily through i.p. with a small dose for certain days (usually 4–8 days), 4 days for our study. Mice were observed daily after the injection and we did not observe any Mn2+ induced toxic clinical signs and symptoms. In toto, we demonstrate that MEMRI can be developed as a biomarker of virus-associated neuropathology. With a thorough understanding of the relationships between MEMRI and neuropathology, monitoring the efficacy of brain therapeutics can be realized for prevention or reversal of virus-associated brain disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following for their technical assistance: Adrian A. Epstein, Jackie Knibbe, Gang Zhang, Sidra P. Akhter, Weizhe Li, Natasha Fields and Tanuja L. Gutti (animal procedures, immunohistology, Nuance EX multispectral imaging system); Bruce Berrigan, Melissa Mellon and Mariano Uberti (MRI); Robin Taylor (cartoon figure, proofreading); and Reed Felderman (proofreading).

Funding: This study is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K25 MH089851, R24 OD018546-01, P01 DA028555, R01 NS36126, P01 NS031492, R01 NS034239, P01 MH64570, P01 NS043985, P30 MH062261 and R01 AG043540 a grant from the Nebraska Research Initiative, and University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Student Fellowship.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Animal Subjects: The use of animals and the procedures performed on the animals in this study are approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Welfare of Animals: The authors further attest that all efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Robertson K, Yosief S. Neurocognitive assessment in the diagnosis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Semin. Neurol. 2014;34:21–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I CHARTER Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clifford DB, Ances BM. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:976–986. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70269-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McArthur JC, Steiner J, Sacktor N, Nath A. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorders: Mind the gap. Ann. Neurol. 2010;67:699–714. doi: 10.1002/ana.22053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill AJ, Kolson DL. Chronic Inflammation and the Role for Cofactors (Hepatitis C, Drug Abuse, Antiretroviral Drug Toxicity, Aging) in HAND Persistence. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorantla S, Poluektova L, Gendelman HE. Rodent models for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dash PK, Gorantla S, Gendelman HE, Knibbe J, Casale GP, Makarov E, Epstein AA, Gelbard HA, Boska MD, Poluektova LY. Loss of neuronal integrity during progressive HIV-1 infection of humanized mice. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:3148–3157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5473-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorantla S, Makarov E, Finke-Dwyer J, Castanedo A, Holguin A, Gebhart CL, Gendelman HE, Poluektova L. Links between progressive HIV-1 infection of humanized mice and viral neuropathogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:2938–2949. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorantla S, Makarov E, Finke-Dwyer J, Gebhart CL, Domm W, Dewhurst S, Gendelman HE, Poluektova LY. CD8+ cell depletion accelerates HIV-1 immunopathology in humanized mice. J. Immunol. 2010;184:7082–7091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorantla S, Sneller H, Walters L, Sharp JG, Pirruccello SJ, West JT, Wood C, Dewhurst S, Gendelman HE, Poluektova L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathobiology studied in humanized BALB/c-Rag2−/−gammac−/− mice. J. Virol. 2007;81:2700–2712. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02010-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorantla S, Gendelman HE, Poluektova LY. Can humanized mice reflect the complex pathobiology of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders? J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:352–362. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9335-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boska MD, Dash PK, Knibbe J, Epstein AA, Akhter SP, Fields N, High R, Makarov E, Bonasera S, Gelbard HA, Poluektova LY, Gendelman HE, Gorantla S. Associations between brain microstructures, metabolites, and cognitive deficits during chronic HIV-1 infection of humanized mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 2014;9:58. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue T, Majid T, Pautler RG. Manganese enhanced MRI (MEMRI): neurophysiological applications. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;22:675–694. doi: 10.1515/RNS.2011.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pautler RG, Koretsky AP. Tracing odor-induced activation in the olfactory bulbs of mice using manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2002;16:441–448. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henriksson J, Tallkvist J, Tjalve H. Transport of manganese via the olfactory pathway in rats: dosage dependency of the uptake and subcellular distribution of the metal in the olfactory epithelium and the brain. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999;156:119–128. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendonca-Dias MH, Gaggelli E, Lauterbur PC. Paramagnetic contrast agents in nuclear magnetic resonance medical imaging. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1983;13:364–376. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(83)80048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geraldes CF, Sherry AD, Brown RD, 3rd, Koenig SH. Magnetic field dependence of solvent proton relaxation rates induced by Gd3+ and Mn2+ complexes of various polyaza macrocyclic ligands: implications for NMR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 1986;3:242–250. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva AC, Bock NA. Manganese-enhanced MRI: an exceptional tool in translational neuroimaging. Schizophr. Bull. 2008;34:595–604. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 1998;17:87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uberti MG, Boska MD, Liu Y. A semi-automatic image segmentation method for extraction of brain volume from in vivo mouse head magnetic resonance imaging using Constraint Level Sets. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009;179:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Scarano F, Martin-Garcia J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavazzi E, Morrison D, Sullivan P, Morgello S, Fischer T. Brain Inflammation is a Common Feature of HIV-Infected Patients Without HIV Encephalitis or Productive Brain Infection. Curr. HIV. Res. 2014 doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140526114956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bade AN, Zhou B, Epstein AA, Gorantla S, Poluektova LY, Luo J, Gendelman HE, Boska MD, Liu Y. Improved visualization of neuronal injury following glial activation by manganese enhanced MRI. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:1027–1036. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9475-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dash PK, Gendelman HE, Roy U, Balkundi S, Alnouti Y, Mosley RL, Gelbard HA, McMillan J, Gorantla S, Poluektova LY. Long-acting nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy elicits potent antiretroviral and neuroprotective responses in HIV-1-infected humanized mice. AIDS. 2012;26:2135–2144. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357f5ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morken TS, Wideroe M, Vogt C, Lydersen S, Havnes M, Skranes J, Goa PE, Brubakk AM. Longitudinal diffusion tensor and manganese-enhanced MRI detect delayed cerebral gray and white matter injury after hypoxia-ischemia and hyperoxia. Pediatr. Res. 2013;73:171–179. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soria G, Aguilar E, Tudela R, Mullol J, Planas AM, Marin C. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging characterization of bilateral structural changes in experimental Parkinson's disease: a T2 relaxometry study combined with longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging and manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the 6-hydroxydopamine rat model. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011;33:1551–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith KD, Paylor R, Pautler RG. R-flurbiprofen improves axonal transport in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease as determined by MEMRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011;65:1423–1429. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu YH, Lee WT, Chang C. Multiparametric MRI evaluation of kainic acid-induced neuronal activation in rat hippocampus. Brain. 2007;130:3124–3134. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aoki I, Naruse S, Tanaka C. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) of brain activity and applications to early detection of brain ischemia. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:569–580. doi: 10.1002/nbm.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis R, Langford D, Masliah E. HIV and antiretroviral therapy in the brain: neuronal injury and repair. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore DJ, Masliah E, Rippeth JD, Gonzalez R, Carey CL, Cherner M, Ellis RJ, Achim CL, Marcotte TD, Heaton RK, Grant I HNRC Group. Cortical and subcortical neurodegeneration is associated with HIV neurocognitive impairment. AIDS. 2006;20:879–887. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218552.69834.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yiannoutsos CT, Ernst T, Chang L, Lee PL, Richards T, Marra CM, Meyerhoff DJ, Jarvik JG, Kolson D, Schifitto G, Ellis RJ, Swindells S, Simpson DM, Miller EN, Gonzalez RG, Navia BA. Regional patterns of brain metabolites in AIDS dementia complex. Neuroimage. 2004;23:928–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masters MC, Ances BM. Role of neuroimaging in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Semin. Neurol. 2014;34:89–102. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holt JL, Kraft-Terry SD, Chang L. Neuroimaging studies of the aging HIV-1-infected brain. J. Neurovirol. 2012;18:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s13365-012-0114-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ratai EM, Pilkenton SJ, Greco JB, Lentz MR, Bombardier JP, Turk KW, He J, Joo CG, Lee V, Westmoreland S, Halpern E, Lackner AA, Gonzalez RG. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals region specific metabolic responses to SIV infection in the macaque brain. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:63-2202-10-63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munoz-Moreno JA, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, Prats A, Negredo E, Garolera M, Perez-Alvarez N, Molto J, Gomez G, Clotet B. Nadir CD4 cell count predicts neurocognitive impairment in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2008;24:1301–1307. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kallianpur KJ, Shikuma C, Kirk GR, Shiramizu B, Valcour V, Chow D, Souza S, Nakamoto B, Sailasuta N. Peripheral blood HIV DNA is associated with atrophy of cerebellar and subcortical gray matter. Neurology. 2013;80:1792–1799. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318291903f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burdo TH, Lackner A, Williams KC. Monocyte/macrophages and their role in HIV neuropathogenesis. Immunol. Rev. 2013;254:102–113. doi: 10.1111/imr.12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grunecker B, Kaltwasser SF, Peterse Y, Samann PG, Schmidt MV, Wotjak CT, Czisch M. Fractionated manganese injections: effects on MRI contrast enhancement and physiological measures in C57BL/6 mice. NMR Biomed. 2010;23:913–921. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.