Abstract

Background and purpose

Depressed mood is a common psychiatric problem associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD), and studies have suggested a benefit of rasagiline treatment.

Methods

ACCORDO (see the 1) was a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the effects of rasagiline 1 mg/day on depressive symptoms and cognition in non-demented PD patients with depressive symptoms. The primary efficacy variable was the change from baseline to week 12 in depressive symptoms measured by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-IA) total score. Secondary outcomes included change from baseline to week 12 in cognitive function as assessed by a comprehensive neuropsychological battery; Parkinson’s disease quality of life questionnaire (PDQ-39) scores; Apathy Scale scores; and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) subscores.

Results

One hundred and twenty-three patients were randomized. At week 12 there was no significant difference between groups for the reduction in total BDI-IA score (primary efficacy variable). However, analysis at week 4 did show a significant difference in favour of rasagiline (marginal means difference ± SE: rasagiline −5.46 ± 0.73 vs. placebo −3.22 ± 0.67; P = 0.026). There were no significant differences between groups on any cognitive test. Rasagiline significantly improved UPDRS Parts I (P = 0.03) and II (P = 0.003) scores versus placebo at week 12. Post hoc analyses showed the statistical superiority of rasagiline versus placebo in the UPDRS Part I depression item (P = 0.04) and PDQ-39 mobility (P = 0.007) and cognition domains (P = 0.026).

Conclusions

Treatment with rasagiline did not have significant effects versus placebo on depressive symptoms or cognition in PD patients with moderate depressive symptoms. Although limited by lack of correction for multiple comparisons, post hoc analyses signalled some improvement in patient-rated cognitive and depression outcomes.

Keywords: cognition, depression, Parkinson’s disease, rasagiline

Introduction

Depressed mood is one of the most common psychiatric problems associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD), affecting up to 50% of PD patients 1,2. Even in patients with early disease, the presence of depressed mood has been found to be a significant predictor of more impairment in activities of daily living (ADLs) and increased need for symptomatic therapy of PD 3. Although there have been positive studies 4, treatment with classic antidepressants has not been found to be consistently effective versus placebo in clinical trials 5,6. It is thought that depression in PD arises from a complex interaction of psychological and neuropathological factors. There is some evidence that the type of depression in PD is distinct from non-parkinsonian depression. The prevalence of depression is higher in PD patients than in other similarly disabled patients 7, and it has been suggested that PD patients have comparatively higher rates of anxiety and pessimism, and less guilt and self-reproach 8,9. Clinically, depressed mood may fluctuate with motor function, improving during the ‘on’ state and worsening during the ‘off’ state 10.

Increasing evidence from epidemiological studies indicates that depression also affects cognition and is a risk factor for dementia. Cognitive impairment is also common in PD and includes impairments in attention encoding memory and visuospatial and executive dysfunctions 11, the latter being mainly attributed to the disruption of the fronto-striatal circuitry.

The clinical efficacy of rasagiline is well established 12. In the ADAGIO study, treatment with rasagiline was reported to improve mood symptoms on the non-motor experiences of daily living 13,14. In addition, results from a small randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study have also suggested that rasagiline may exert beneficial effects on attention and executive abilities in non-demented PD patients with cognitive impairment 15. The aims of this randomized controlled study were to evaluate the potential beneficial effect of rasagiline 1 mg/day on depressive symptoms and to explore the relationship of depressive symptoms with cognitive function in idiopathic PD patients without dementia.

Methods

Study setting and trial registration

This was a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rasagiline 1 mg/day in PD patients with depression. The study was conducted from 5 March 2010 to 2 July 2012 at 12 university hospitals or Parkinson centres in Italy. It was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and was approved by appropriate institutional review boards; all patients provided written informed consent to participate. The study is registered with the European Clinical Trials Database (EUDRA-CT number: 2009-011144-19).

Study population

Key inclusion criteria were diagnosis of PD (at least two of three cardinal signs – resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity – and no other known or suspected cause of parkinsonism), age ≥40 and <80 years, and Hoehn−Yahr stage ≥1 and ≤3 (on treatment). Eligible patients had a Beck Depression Inventory (version BDI-IA) score ≥15 and should have been under stable (4 weeks prior to baseline) dopaminergic treatment. All stable doses of dopamine receptor agonists, levodopa/carbidopa, levodopa/benserazide and catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) inhibitors were permitted.

This study was specifically designed to be conducted in PD patients with a stable motor component, and thus patients with motor fluctuations (the presence of which may be associated with mood) were excluded from the study. Other key exclusion criteria included previous deep brain stimulation surgery; Mini-Mental State Examination <26; a diagnosis of current or a history of major depressive episode according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria within 1 year before recruitment into the study; and presence of psychotic symptoms, e.g. hallucination and delirium. Treatment with antidepressants, antipsychotics, cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, amantadine, anticholinergics, and the hypnotics zaleplon, zolpidem, zopiclone and antihistamines were not allowed and must have been discontinued at least 4 weeks prior to study initiation. Patients currently or previously treated with selegiline (<90 days prior to randomization) were also excluded.

Study design

Patients underwent screening and baseline assessments at visits 1 and 2 and those who met eligibility criteria were randomized 1:1 to the addition of rasagiline 1 mg/day or matching placebo according to a computer-generated randomization list. Site personnel, patients and sponsor were blinded to treatment assignment. Subsequent study visits were undertaken at weeks 4 (visit 3) and 12 (visit 4; study end). In addition, there was a safety follow-up visit at week 14.

Outcome measures

Evaluations of depressive symptoms (BDI-IA) were performed at baseline, week 4 and week 12 (study completion). Cognitive functions (cognitive test battery) and Apathy Scale (AS) were assessed at baseline and week 12. The cognitive test battery included the noun and verb naming tasks of the Aphasia Neuropsychological Examination (Esame Neuropsicologico per l’Afasia in Italian); Trail Making Test, parts A and B; Cognitive Performance Test for letters and categories; Color Naming, Word Reading and Interference Task of the Stroop Test; Clock Drawing Test; immediate and delayed recall of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Benton Judgment of Line Orientation Test; and the copy task of the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure test. The Parkinson’s disease quality of life questionnaire (PDQ-39) and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Parts I−IV were assessed at baseline and week 12, with additional assessments of UPDRS Parts II (ADL) and III (Motor) at week 4. All assessments were performed in the morning, preferably 2 h after the intake of the morning dose of study medication. All evaluations, with the exception of motor function (assessed by neurologists), were performed by a psychologist, neuropsychologist or physician with adequate experience.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were recorded throughout the study.

Statistical analyses

The primary efficacy variable was the change from baseline to week 12 in depressive symptoms measured by the BDI-IA total score. The primary efficacy analysis was performed on the full-analysis set (FAS) (defined as all randomized patients who took at least one dose of study medication and who had at least one valid post-baseline assessment of the primary efficacy variable). For the primary efficacy end-point, and whenever applicable for the secondary efficacy end-points, the ‘last observation carried forward’ technique was used to handle missing data. Comparisons between the two groups were subjected to an analysis of covariance (ancova) method, fitting the baseline value of BDI-IA as covariate and treatment as a fixed factor. Baseline and safety outcomes were assessed using the safety population, which included all patients who took at least one dose of study drug.

Secondary efficacy outcomes were analysed in the same way as the primary outcome variable and included change from baseline to week 12 in cognitive function as assessed by the neuropsychological battery; PDQ-39 scores; AS scores; and UPDRS Parts II and III subscores.

Post hoc analyses were made for the change from baseline to week 12 in UPDRS Part I (mental) items and PDQ-39 domain scores (eight domains).

Determination of sample size

Based on experience in another PD study 16 and expert opinion, a total sample of 61 evaluable patients in each arm was calculated to provide 80% power to detect a minimum difference of 3.3 points in BDI-IA total score at the 5% two-sided significance level, assuming a standard deviation of 6.4.

Results

Patient disposition

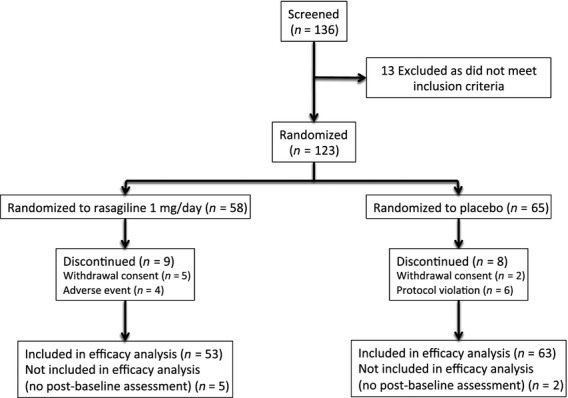

One hundred and twenty-three patients were enrolled and randomized in the study (Fig.1; Table1). Seven patients were randomized but did not have a valid post-baseline assessment of the primary efficacy variable. The safety population included 123 (100.0%) patients and the FAS included 116 (94.3%) patients. A total of 106 (86.2%) patients completed the study.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics (safety population)

| Parameter (safety population) | Rasagiline (N = 58) | Placebo (N = 65) |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 27 (46.6%) | 38 (58.5%) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 66.0 ± 8.74 | 66.1 ± 8.35 |

| Number of years in education, mean ± SD | 9.1 ± 4.33 | 9.6 ± 4.49 |

| Duration of PD (years), mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 3.17 | 4.8 ± 3.78 |

| Hoehn and Yahr staging, n (%) | ||

| Stage 1 | 9 (15.5%) | 9 (13.8%) |

| Stage 1.5 | 12 (20.7%) | 11 (16.9%) |

| Stage 2 | 29 (50.0%) | 34 (52.3%) |

| Stage 2.5 | 5 (8.6%) | 6 (9.2%) |

| Stage 3 | 3 (5.2%) | 5 (7.7%) |

| BDI-IA score, mean ± SD | 20.2 ± 5.34 | 20.1 ± 6.56 |

| MMSE, mean ± SD | 28.7 ± 1.96 | 28.8 ± 1.21 |

| Current PD medications, n (%) | ||

| Levodopa | 36 (62.1%) | 45 (69.2%) |

| Levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone | 5 (8.6%) | 14 (21.5%) |

| Me-levodopa | 7 (12.1%) | 4 (6.2%) |

| Ropinirole | 9 (15.5%) | 8 (12.3%) |

| Pramipexole | 19 (32.8%) | 31 (47.7%) |

| Rotigotine | 5 (8.6%) | 3 (4.6%) |

| Entacapone | 2 (3.4%) | – |

PD, Parkinson’s disease; BDI-IA, Beck Depression Inventory; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Demographics, baseline characteristics and concomitant medications

Patient demographics and baseline PD characteristics were well matched, with no significant differences between groups (P > 0.05 for all) (Table1).

Efficacy

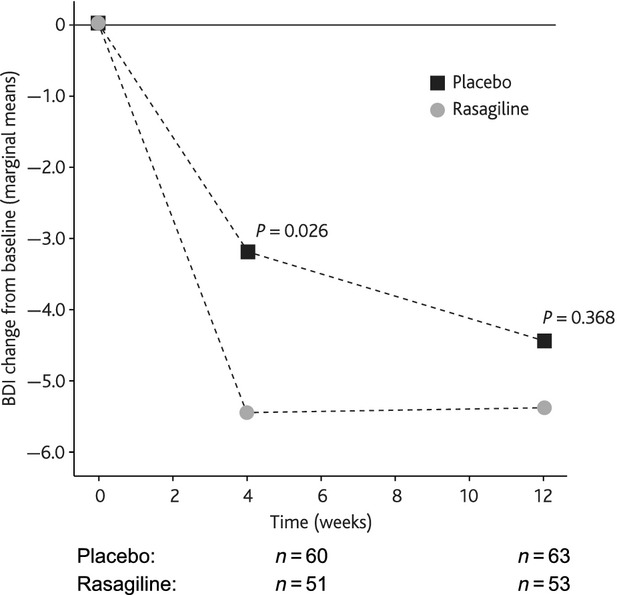

After 4 weeks of treatment, there was a significant difference between the BDI-IA total score reduction from baseline between groups (marginal means difference ± SE: rasagiline −5.46 ± 0.73 vs. placebo −3.22 ± 0.67; P = 0.026). However, after 12 weeks of treatment (primary efficacy end-point) there was no significant difference between groups (marginal means difference ± SE: rasagiline −5.40 ± 0.79 vs. placebo −4.43 ± 0.73; P = 0.368). Figure2 shows that the response to rasagiline remained stable from week 4 but there was an improvement with placebo.

Figure 2.

BDI-IA total score change from baseline.

After 12 weeks of treatment there were no significant differences between groups on any of the individual cognitive tests contained within the battery (Table2).

Table 2.

Cognitive battery scores

| Variable (FAS population) | Baseline score (mean ± SD) | Change from baseline at week 12 (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Language | ||

| ENPA | ||

| Placebo | 17.90 ± 3.23 (n = 63) | −0.44 ± 2.85 (n = 61) |

| Rasagiline | 17.03 ± 4.37 (n = 53) | −0.68 ± 2.85 (n = 52) |

| Memory | ||

| RAVLT immediate recall | ||

| Placebo | 34.49 ± 37.59 (n = 63) | −1.58 ± 38.51 (n = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 36.85 ± 11.75 (n = 53) | 2.27 ± 10.79 (n = 52) |

| RAVLT delayed recall | ||

| Placebo | 6.57 ± 3.34 (n = 63) | 1.21 ± 2.53 (n = 61) |

| Rasagiline | 7.13 ± 3.65 (n = 53) | 0.92 ± 2.27 (n = 52) |

| Attention | ||

| Word reading Stroop test | ||

| Placebo | 48.10 ± 17.85 (n = 62) | −0.92 ± 13.64 (n = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 46.08 ± 18.48 (n = 53) | −1.29 ± 9.57 (n = 52) |

| Color naming Stroop test | ||

| Placebo | 31.37 ± 13.89 (n = 62) | 0.32 ± 9.71 (n = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 31.87 ± 9.94 (n = 53) | −1.65 ± 5.85 (n = 52) |

| Trails A | ||

| Placebo | 68.97 ± 53.32 (n = 63) | −7.78 ± 46.81 (n = 59) |

| Rasagiline | 58.31 ± 30.17 (n = 52) | −1.10 ± 17.40 (n = 51) |

| Frontal functions | ||

| Trails B | ||

| Placebo | 160.09 ± 97.02 (n = 54) | 4.28 ± 70.04 (n = 50) |

| Rasagiline | 157.87 ± 86.75 (n = 47) | −4.22 ± 53.03 (n = 46) |

| Trails B−A | ||

| Placebo | 99.56 ± 77.03 (n = 54) | 6.24 ± 69.34 (n = 50) |

| Rasagiline | 100.79 ± 82.32 (n = 47) | −3.50 ± 48.63 (n = 46) |

| Stroop test non-congruent correct answers | ||

| Placebo | 17.41 ± 13.21 (n = 61) | 0.58 ± 13.18 (n = 59) |

| Rasagiline | 17.10 ± 7.47 (n = 52) | 0.39 ± 4.30 (n = 51) |

| Clock Drawing Test | ||

| Placebo | 8.97 ± 10.19 (n = 63) | −0.63 ± 12.88 (n = 59) |

| Rasagiline | 6.88 ± 3.44 (n = 53) | 0.33 ± 3.40 (n = 52) |

| CPT for letter | ||

| Placebo | 27.00 ± 11.45 (n = 63) | 0.36 ± 7.18 (n = 61) |

| Rasagiline | 29.13 ± 14.44 (n = 53) | −2.12 ± 9.35 (n = 52) |

| CPT for categories | ||

| Placebo | 22.40 ± 15.10 (n = 63) | 0.62 ± 6.85 (n = 61) |

| Rasagiline | 22.28 ± 14.46 (n = 52) | 1.71 ± 10.86 (n = 50) |

| Visuospatial function | ||

| BJLOT | ||

| Placebo | 19.38 ± 7.50 (n = 63) | 0.84 ± 7.18 (n = 61) |

| Rasagiline | 21.85 ± 8.40 (n = 52) | 0.98 ± 3.73 (n = 51) |

| ROCF copy | ||

| Placebo | 26.83 ± 12.23 (n = 63) | 0.07 ± 11.21 (n = 56) |

| Rasagiline | 28.50 ± 6.84 (n = 52) | −1.13 ± 6.88 (n = 51) |

FAS, full-analysis set; ENPA, Aphasia Neuropsychological Examination (Esame Neuropsicologico per l’Afasia in Italian); RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Trails, Trail Making Test, parts A and B; CPT, Cognitive Performance Test for letters and categories; BJLOT, Benton Judgment of Line Orientation Test; ROCF, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure test.

Treatment with rasagiline significantly improved UPDRS Part II scores versus placebo at week 12 (marginal means difference ± SE: rasagiline −1.37 ± 0.35 vs. placebo 0.06 ± 0.32; P = 0.003). There was no significant effect of treatment on UPDRS Part III subscores (rasagiline −0.88 ± 0.56 vs. placebo 0.42 ± 0.51; P = 0.090). There was a significant difference between groups on UPDRS Part I subscores (rasagiline −0.96 ± 0.16 vs. placebo −0.49 ± 0.15; P = 0.030) (Table3). Post hoc analysis of individual UPDRS Part I items also found a significant between-group difference for depression (rasagiline −0.59 ± 0.09 vs. placebo −0.28 ± 0.08; P = 0.041). There were no significant differences in other individual UPDRS Part I items.

Table 3.

Change from baseline in UPDRS subdomains

| Variable (FAS population) | Baseline score (mean ± SD) | Change from baseline at week 12 (marginal mean ± SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Subdomains of UPDRS | ||

| Mentation | ||

| Placebo | 0.37 ± 0.52 (N = 63) | −0.04 ± 0.05 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 0.38 ± 0.53 (N = 52) | −0.09 ± 0.06 (N = 52) |

| Thought disorder | ||

| Placebo | 0.27 ± 0.48 (N = 63) | −0.04 ± 0.04 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 0.17 ± 0.43 (N = 52) | −0.07 ± 0.05 (N = 52) |

| Depression | ||

| Placebo | 1.68 ± 0.74 (N = 63) | −0.28 ± 0.08 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 1.56 ± 0.70 (N = 52) | −0.59 ± 0.09* (N = 52) |

| Motivation/initiative | ||

| Placebo | 1.13 ± 0.87 (N = 63) | −0.07 ± 0.08 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 1.06 ± 0.94 (N = 52) | −0.33 ± 0.09 (N = 52) |

UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; FAS, full-analysis set.

Significant difference.

There was no significant effect of treatment on PDQ-39 total scores (rasagiline −6.28 ± 2.24 vs. placebo −0.73 ± 2.06; P = 0.074). However, a post hoc analysis of PDQ-39 domains found significant differences favouring rasagiline in PDQ-mobility scores (P = 0.007) and PDQ-cognition scores (P = 0.026) (Table4). No significant between-group differences were noted for apathy as assessed by the AS.

Table 4.

Change from baseline in PDQ-39 domains

| Variable (FAS population) | Baseline score (mean ± SD) | Change from baseline at week 12 (marginal mean ± SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Domains of PDQ-39 | ||

| Mobility | ||

| Placebo | 35.01 ± 21.44 (N = 62) | 2.83 ± 2.33 (N = 59) |

| Rasagiline | 31.37 ± 25.26 (N = 53) | −6.28 ± 2.62* (N = 52) |

| Activities of daily living | ||

| Placebo | 30.22 ± 22.65 (N = 63) | 1.51 ± 2.33 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 24.47 ± 20.13 (N = 53) | −3.64 ± 2.62 (N = 52) |

| Emotional well-being | ||

| Placebo | 43.16 ± 18.75 (N = 63) | −2.33 ± 2.23 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 38.19 ± 19.88 (N = 53) | −5.66 ± 2.54 (N = 52) |

| Stigma | ||

| Placebo | 32.18 ± 22.59 (N = 61) | −0.27 ± 2.54 (N = 58) |

| Rasagiline | 17.46 ± 20.19 (N = 53) | −4.58 ± 2.90 (N = 51) |

| Social support | ||

| Placebo | 13.45 ± 18.15 (N = 63) | 1.03 ± 2.43 (N = 59) |

| Rasagiline | 8.02 ± 12.11 (N = 53) | −1.44 ± 2.76 (N = 51) |

| Cognition | ||

| Placebo | 28.42 ± 17.91 (N = 61) | 2.41 ± 2.03 (N = 59) |

| Rasagiline | 25.47 ± 19.06 (N = 53) | −4.00 ± 2.28* (N = 52) |

| Communication | ||

| Placebo | 23.55 ± 24.98 (N = 62) | −1.53 ± 2.22 (N = 59) |

| Rasagiline | 16.34 ± 20.07 (N = 53) | −6.60 ± 2.52 (N = 51) |

| Bodily discomfort | ||

| Placebo | 36.90 ± 24.26 (N = 63) | 2.72 ± 2.65 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 33.80 ± 23.42 (N = 53) | 2.01 ± 2.97 (N = 52) |

| Total | ||

| Placebo | 51.65 ± 26.88 (N = 62) | −1.03 ± 2.33 (N = 60) |

| Rasagiline | 41.46 ± 23.03 (N = 52) | −6.24 ± 2.69 (N = 51) |

PDQ-39, Parkinson’s disease quality of life questionnaire; FAS, full-analysis set.

Significant difference.

Safety

A total of 15 vs. 17 patients (rasagiline versus placebo group, respectively) reported at least one TEAE; most TEAEs were mild or moderate. No TEAE was reported more than two times in either group. Two patients in the rasagiline group (radius fracture; melanocytic nevus) and one in the placebo group (polyneuropathy in malignant disease and respiratory disorder) reported a serious TEAE. Four patients in the rasagiline group withdrew due to an TEAE (aggravated dyskinesia, vertigo, left trunk flexion due to PD, nausea) versus none in the placebo group.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first prospective study exploring the efficacy of rasagiline versus placebo on depressive symptoms in PD. The primary end-point, change from baseline to week 12, was not achieved although a significant difference favouring rasagiline was observed at 4 weeks. Likewise, the pre-planned analyses did not find any significant differences in cognitive function.

One potential reason for the lack of efficacy on depressive symptoms may be the BDI-IA inclusion criteria, which selected patients with at least a moderate severity of depressive symptoms (baseline BDI-IA scores were 20 in both groups). It may be that the effects of simply enhancing the dopaminergic system by inhibiting dopamine metabolism are not enough to treat moderate to severe depressive symptoms. The only antiparkinsonian therapy that has been shown in a randomized controlled trial to improve depressive symptoms in PD is pramipexole (patients in the pramipexole trial had milder baseline BDI scores of 18.7–19.5) 16, which has been shown to bind with high affinity to dopamine D3 receptors in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and medial and lateral thalamus (all known to have some relation to depression) 17. In addition, the improvement in depressive symptomology in the placebo group between weeks 4 and 12 probably reflects the positive influence of being in a study for depression (e.g. increased contact with healthcare professionals and expectations of improvement) 18.

By contrast, post hoc analysis of the UPDRS Part I did show a significant effect on the depression item. This probably reflects the less comprehensive assessment of depressive symptoms by just one item versus a 21-item questionnaire specifically designed to assess depression. Interestingly, the ADAGIO delayed-start study, which was conducted in patients with early PD and included an assessment of non-motor experiences of daily living (nM-EDL) in the placebo-controlled phase, also found that treatment with rasagiline 1 mg/day significantly improved the depression item versus placebo. Although baseline depression was not specifically assessed in ADAGIO, baseline nM-EDL scores were low suggesting that patients had less severe symptoms 13,14. More recently, an analysis of the 191 ADAGIO patients who were concomitantly treated with antidepressants found that depression and cognition item scores improved significantly in the rasagiline group compared with the placebo group 19. Importantly, the effect on depressive symptoms remained significant after controlling for motor change, thereby confirming some sort of role for the dopamine system in depression in PD.

Taken together, the secondary efficacy results do not show a clear effect of rasagiline on cognitive function. Thus far, only one small study has been published exploring the efficacy of rasagiline on cognitive function 15. This study conducted in 55 PD patients found that rasagiline provides significant improvements in attention (as measured by digit span) and executive functions (as measured by verbal fluency). However, the study specifically excluded patients with a geriatric depression scale score >13, thereby excluding patients with all but the mildest depressive symptoms. The discordance between the results of the earlier study and ours might reflect different methodologies used to assess cognitive functions and different sizes in PD samples.

As with other studies, treatment with rasagiline improved both UPDRS mental and ADL scores 12. The effects on motor function did not reach statistical significance but all patients already had a stable motor component and there was no requirement for additional therapy. Although improvements in ADL are mostly driven by motor function, they are derived from the patients self-report over the past week and also include non-motor aspects of the disease. From the patients’ perspective, overall quality of life (as self-reported using the PDQ-39) was not found to significantly improve with rasagiline, but patients were able to identify improvements in mobility and in cognition. The improvement of the PDQ-mobility item is expected because it reflects the trend towards improvement of UPDRS motor scores. However, the effects on cognition are not consistent with the results of objective neuropsychological results. As already noted, the PDQ-39 is a self-administered test, and thus the results reflect patients’ own impressions of their overall cognitive status versus the very specific cognitive tests employed in the test battery.

The strengths of this study include its randomized, placebo-controlled design, prospective nature and its reasonable size. However, our study has several important limitations. Patients with milder depressive symptoms, those already treated with antidepressants and those with motor fluctuations were excluded from the study and it was only of a short (12 weeks) duration. Recruitment was slow, and eventually there were fewer than the estimated 61 patients in the FAS for the rasagiline group – implying that the study could be underpowered for testing the primary and secondary outcomes. In addition, the large number of tests (including 13 cognitive tests) employed meant that there were a high number of statistical tests with no correction for multiplicity and the analyses of UPDRS Part I items and PDQ domains were conducted post hoc. Finally, it should be noted that, at the time this study was conducted, the concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in PD was not universally accepted, and as such no data were available on the MCI status of patients in this study. Future studies would need to collect such MCI data.

In summary, rasagiline was not found to have significant effects versus placebo in PD patients with moderately severe depressive symptoms. However, post hoc analyses and patient self-reported measures do appear to signal some improvements in both depression and cognition. Taken together with the results of other recently reported analyses 13,19, this study supports the suggestion that studies in PD patients with milder depressive symptoms are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Lundbeck Italia SpA. We thank Anita Chadha-Patel PhD (ACP Clinical Communications Ltd funded by Lundbeck Italia SpA) for medical writing support (literature searching and editing), and Giorgio Reggiardo PhD and Valentina Mirisola PhD (both of Medi Service, Italy, and funded by Lundbeck Italia SpA) who conducted the statistical analysis.

Appendix

ACCORDO co-investigators were Monica Bandettini di Poggio, Paolo Del Dotto, Elena Di Battista, Laura Ferigo, Francesca Morgante, Daniela Murgia, Manuela Pilleri, Valerio Pisani, Silvana Tesei, Astrid Maria Thomas, Maurizio Zibetti and Marianna Amboni.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

All authors’ institutions, except for G. Santangelo, received grants from Lundbeck Italia for participating in the study. In addition, P. Barone reports grants from Lundbeck Italia during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Lundbeck Italia, UCB and Otsuka, and grants from Zambon. G. Santangelo, L. Morgante, M. Onofrj, G. Meco, G. Cossu, G. Pezzoli report honoraria from Lundbeck Italia; G. Abbruzzese received honoraria for lecturing by Abbvie and Lundbeck Italia; U. Bonuccelli received honoraria for consulting and speeches at meetings from UCB, Lundbeck Italia, Novartis and GSK; P. Stanzione reports honoraria from UCB; L. Lopiano and A. Antonini report fees for speaker-related activities from Lundbeck Italia, AbbVie and UCB; M. Tinazzi received honoraria for lectures for Chiesi and Lundbeck Italia.

References

- Dooneief G, Mirabello E, Bell K, et al. An estimate of the incidence of depression in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:305–307. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530270125028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Aarsland D, Cummings JL. The occurrence of depression in Parkinson’s disease. A community-based study. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:175–179. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550020087019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravina B, Camicioli R, Como PG, et al. The impact of depressive symptoms in early Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;69:342–347. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000268695.63392.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard IH, McDermott MP, Kurlan R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2012;78:1229–1236. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182516244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D, Morales KH, Moberg PJ, et al. Antidepressant studies in Parkinson’s disease: a review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1161–1169. doi: 10.1002/mds.20555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menza M, Dobkin RD, Marin H, et al. A controlled trial of antidepressants in patients with Parkinson disease and depression. Neurology. 2009;72:886–892. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336340.89821.b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehmann TS, Beninger RJ, Gawel MJ, Riopelle RJ. Depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a comparison with disabled control subjects. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1990;3:3–9. doi: 10.1177/089198879000300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D, Burn DJ. Parkinson’s disease: the quintessential neuropsychiatric disorder. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1022–1031. doi: 10.1002/mds.23664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leentjens AF. Depression in Parkinson’s disease: conceptual issues and clinical challenges. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:120–126. doi: 10.1177/0891988704267456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch A, Schneider CB, Wolz M, et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: severity and correlation with motor complications. Neurology. 2013;80:800–809. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318285c0ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnall AJ, Rochester L, Burn DJ. Mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Age Ageing. 2013;42:567–576. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack PL. Rasagiline: a review of its use in the treatment of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:1083–1097. doi: 10.1007/s40263-014-0206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poewe W, Hauser R, Lang A. Effects of rasagiline on the progression of non-motor scores of the MDS-UPDRS. Mov Disord. 2015;30:589–592. doi: 10.1002/mds.26124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascol O, Fitzer-Attas CJ, Hauser R, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease (the ADAGIO study): prespecified and post-hoc analyses of the need for additional therapies, changes in UPDRS scores, and non-motor outcomes. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:415–423. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanagasi HA, Gurvit H, Unsalan P, et al. The effects of rasagiline on cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease patients without dementia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1851–1858. doi: 10.1002/mds.23738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone P, Poewe W, Albrecht S, et al. Pramipexole for the treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:573–580. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70106-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi K, Ishii K, Oda K, Mizusawa H, Ishiwata K. Binding of pramipexole to extrastriatal dopamine D2/D3 receptors in the human brain: a positron emission tomography study using 11C-FLB 457. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S. The placebo effect. Psychiatr Bull. 2006;30:185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KM, Eyal E. Weintraub D ADAGIO Investigators. Combined rasagiline and antidepressant use in Parkinson disease in the ADAGIO study: effects on nonmotor symptoms and tolerability. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:88–95. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]