Abstract

Background

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIO) is the most common secondary form of osteoporosis, and glucocorticoid users are at increased risk for fracture compared with nonusers. There is no established relationship between bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture risk in GIO. We used 3 Tesla (T) MRI to investigate how proximal femur microarchitecture is altered in subjects with GIO.

Methods

This study had institutional review board approval. We recruited 6 subjects with long-term (> 1 year) glucocorticoid use (median age = 52.5 (39.2–58.7) years) and 6 controls (median age = 65.5 [62–75.5] years). For the nondominant hip, all subjects underwent dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to assess BMD and 3T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, 3D FLASH) to assess metrics of bone microarchitecture and strength.

Results

Compared with controls, glucocorticoid users demonstrated lower femoral neck trabecular number (−50.3%, 1.12 [0.84–1.54] mm−1 versus 2.27 [1.88–2.73] mm−1, P = 0.02), plate-to-rod ratio (−20.1%, 1.48 [1.39–1.71] versus 1.86 [1.76–2.20], P = 0.03), and elastic modulus (−64.8% to −74.8%, 1.54 [1.22–3.19] GPa to 2.31 [1.87–4.44] GPa versus 6.15 [5.00–7.09] GPa to 6.59 [5.58–7.31] GPa, P < 0.05), and higher femoral neck trabecular separation (+192%, 0.705 [0.462–1.00] mm versus 0.241 [0.194–0.327] mm, P = 0.02). There were no differences in femoral neck trabecular thickness (−2.7%, 0.193 [0.184–0.217] mm versus 0.199 [0.179–0.210] mm, P = 0.94) or femoral neck BMD T-scores (+20.7%, −2.1 [−2.8 to −1.4] versus −2.6 [−3.3 to −2.5], P = 0.24) between groups.

Conclusion

The 3T MRI can potentially detect detrimental changes in proximal femur microarchitecture and strength in long-term glucocorticoid users.

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIO) is the most common secondary form of osteoporosis,1 with 30– 50% of glucocorticoid users suffering a fragility fracture.1,2 Additionally, compared with nonusers, glucocorticoid users’ risk of hip and vertebral fracture is increased 7- to 17-fold.3

The standard-of-care test used to diagnose osteoporosis is dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) estimation of areal bone mineral density (BMD). However, DXA underestimates fracture risk in GIO. During the first 3–6 months after the start of glucocorticoid therapy, BMD does not substantially decline in glucocorticoid users, but fracture risk rises 75%.1,4 The lack of an established relationship between BMD and fracture risk in GIO,5 suggests that glucocorticoids affect bone quality and strength in a way not captured by DXA.

Bone microarchitecture refers to the unique size, shape, and arrangement of bone tissue on the microstructural level. Because bone microarchitecture is an important contributor to bone strength independent of BMD, the World Health Organization included microarchitectural deterioration in the disease definition of osteoporosis.6,7 Since Harvey Cushing’s 1932 description of the effects of hypercortisolism on bone,8 it has been known that glucocorticoids predominantly affect sites rich in trabecular bone, causing deterioration in bone microarchitecture.1,8

The goal of this study was to use high-resolution (0.234 mm × 0.234 mm × 1.5 mm) 3 Tesla (T) MRI to determine how proximal femur microarchitecture and strength are adversely affected in long-term (> 12 months) glucocorticoid-users compared with controls.

Materials and Methods

Subject Recruitment

This study had institutional review board approval and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. From the Osteoporosis Center at our institution, we recruited six subjects with long-term (> 1 year) cumulative glucocorticoid use (2 males, 4 females; median age = 52.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 19.5 years); median body mass index (BMI) = 22.8 kg/m2 (IQR = 6.6 kg/m2); glucocorticoid use indicated for pulmonary and rheumatic diseases) and six healthy subjects who did not use glucocorticoids (2 males, 4 females; median age = 65.5 years [IQR = 10.5 years]; median BMI = 23.1 kg/m2 [IQR = 6.8 kg/m2]) (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Control Subjects’ Demographic, DXA, and MRI Data

| Subject no. |

Gender | Age | Body mass index |

Glucocorticoid use |

Femoral neck BMD T-score |

Total hip BMD T-score |

Tb.Th. (mm) |

Tb.Sp. (mm) |

Tb.N. (1/mm) |

Plate-to-rod ratio |

ESI (GPa) |

EML (GPa) |

EAP (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 66.00 | 23.13 | No | −3.7 | −3.0 | 0.184 | 0.221 | 2.47 | 1.84 | 6.52 | 6.62 | 6.76 |

| 2 | Male | 65.00 | 27.84 | No | −2.8 | −2.5 | 0.203 | 0.363 | 1.77 | 1.88 | 5.19 | 5.20 | 5.74 |

| 3 | Female | 72.00 | 17.37 | No | −2.5 | −1.9 | 0.166 | 0.216 | 2.62 | 2.26 | 6.37 | 6.46 | 6.56 |

| 4 | Female | 62.00 | 22.57 | No | −2.5 | −2.3 | 0.195 | 0.129 | 3.09 | 2.18 | 8.81 | 8.92 | 8.97 |

| 5 | Female | 62.00 | 24.17 | No | −2.4 | −2.4 | 0.223 | 0.262 | 2.06 | 1.77 | 5.94 | 5.87 | 6.62 |

| 6 | Female | 74.00 | 18.84 | No | −3.1 | −2.1 | 0.206 | 0.315 | 1.92 | 1.72 | 4.44 | 4.67 | 5.12 |

BMD = bone mineral density; Tb.Th. = femoral neck trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp. = trabecular separation; Tb.N. = trabecular number; E = Elastic Modulus With Simulated Loading in Three Different Directions: SI = superior-inferior; ML = medial-lateral; AP = anterior-posterior.

TABLE 2.

Glucocorticoid Users’ Demographics, DXA, and MRI data

| Subject no. |

Gender | Age | Body mass index |

Glucocorticoid use |

Femoral neck BMD T-score |

Total hip BMD T-score |

Tb.Th. (mm) |

Tb.Sp. (mm) |

Tb.N. (1/mm) |

Plate-to-rod ratio |

ESI (GPa) |

EML (GPa) |

EAP (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Female | 34.00 | 17.53 | Yes | −1.1 | −0.8 | 0.189 | 0.963 | 0.87 | 1.47 | 1.30 | 1.48 | 2.09 |

| 8 | Female | 48.00 | 20.60 | Yes | −2.6 | −1.0 | 0.176 | 0.806 | 1.02 | 1.50 | 1.71 | 1.95 | 2.54 |

| 9 | Male | 57.00 | 25.84 | Yes | −2.9 | −1.1 | 0.187 | 1.140 | 0.75 | 1.23 | 1.01 | .99 | 1.48 |

| 10 | Male | 58.00 | 24.30 | Yes | −2.8 | −1.7 | 0.245 | 0.222 | 2.14 | 2.00 | 6.67 | 6.52 | 7.43 |

| 11 | Female | 41.00 | 28.94 | Yes | −1.5 | −1.4 | 0.208 | 0.605 | 1.23 | 1.44 | 2.03 | 2.07 | 3.44 |

| 12 | Female | 61.00 | 21.90 | Yes | −1.6 | −1.7 | 0.198 | 0.542 | 1.35 | 1.62 | 1.39 | 1.33 | 2.01 |

BMD = bone mineral density; Tb.Th. = femoral neck trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp. = trabecular separation; Tb.N. = trabecular number; E = elastic modulus with simulated loading in three different directions: SI = superior-inferior; ML = medial-lateral AP = anterior-posterior.

DXA and MRI Scanning

All subjects underwent 3T MRI (Siemens Skyra, Erlangen, Germany) of the nondominant hip for quantitative assessment of proximal femur microarchitecture. Subjects were scanned using a 26-element receive coil setup and a three-dimensional (3D) fast low-angle shot sequence (3D FLASH, TR/TE = 37 ms/4.92 ms, flip angle = 25°, bandwidth = 130 Hz/pixel, field of view = 100 mm, matrix = 512 × 512, in-plane voxel dimension = 0.234 mm × 0.234 mm, 60 coronal slices, slice thickness = 1.5 mm, parallel imaging (GRAPPA) factor = 2, scan time = 15 min 18 s). During MRI scanning, the hip was immobilized by a sandbag laterally secured by a large Velcro strap. All subjects also underwent dualenergy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA, Hologic, Waltham, MA) of the same hip to compute total hip and femoral neck areal bone mineral density.

MR Image Analysis

First, we generated bone volume fraction maps (fractional occupancy of bone within each voxel) from the MR images. To do this, the grayscale values of the images were linearly scaled to cover the range from 0 to 100%, with pure marrow and bone intensity in the femur having minimum and maximum values, respectively.9 This approach allows us to account for: (i) both partial volume effects and the presence of red marrow, which may have different signal intensity than fatty marrow and (ii) differences in MR image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) between patients. We do note that there is a minimum SNR required (~10–15) to reliably perform quantitative analysis of microarchitecture.10 Next, a musculoskeletal radiologist (G.C., 4.5 years of experience) selected the central slice of the proximal femur images and then selected a 10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm cubic volume of interest (VOI) in the center of the femoral neck.

To quantitatively assess proximal femur microarchitecture, we applied fuzzy distance transform11 and finite element analysis12 to the VOIs. In brief, fuzzy distance transform allows accurate measurement of objects at the in vivo resolution regime of micro- MRI by weighting for bone volume fraction,13 and it has been previously been applied in many studies of trabecular bone microarchitecture.10,14 For finite element analysis, each voxel from the VOI was converted into a hexahedral finite element with dimensions corresponding to the voxel size. The material properties of bone were chosen as isotropic and linearly elastic with Young’s modulus (YM) set to be linearly proportional to the bone volume fraction (BVF) value such that YM = 15 GPa × BVF while the Poisson’s ratio was set at 0.3 for all elements.15–17 We performed simulated compressive loading along bone’s superior–inferior, medial–lateral, and anterior–posterior axes by applying 1% strain on the opposite faces of the cubic VOIs while constraining the four faces of the VOI lateral to the compressive direction. The FE system was solved to yield a 3D strain map. Finally, femoral neck elastic modulus (GPa) was obtained as the ratio of the resulting stress to the strain.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS (Somers, NY). Because data were not normally distributed (Wilk-Shapiro test), results are expressed as median values with interquartile ranges. We performed the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test to compare differences in MRI-derived microarchitectural parameters and DXA-derived BMD T-scores between groups. We also performed the nonparametric Spearman rho test to determine the association between DXA-derived BMD T-scores and MRI-derived microarchitectural parameters. A P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

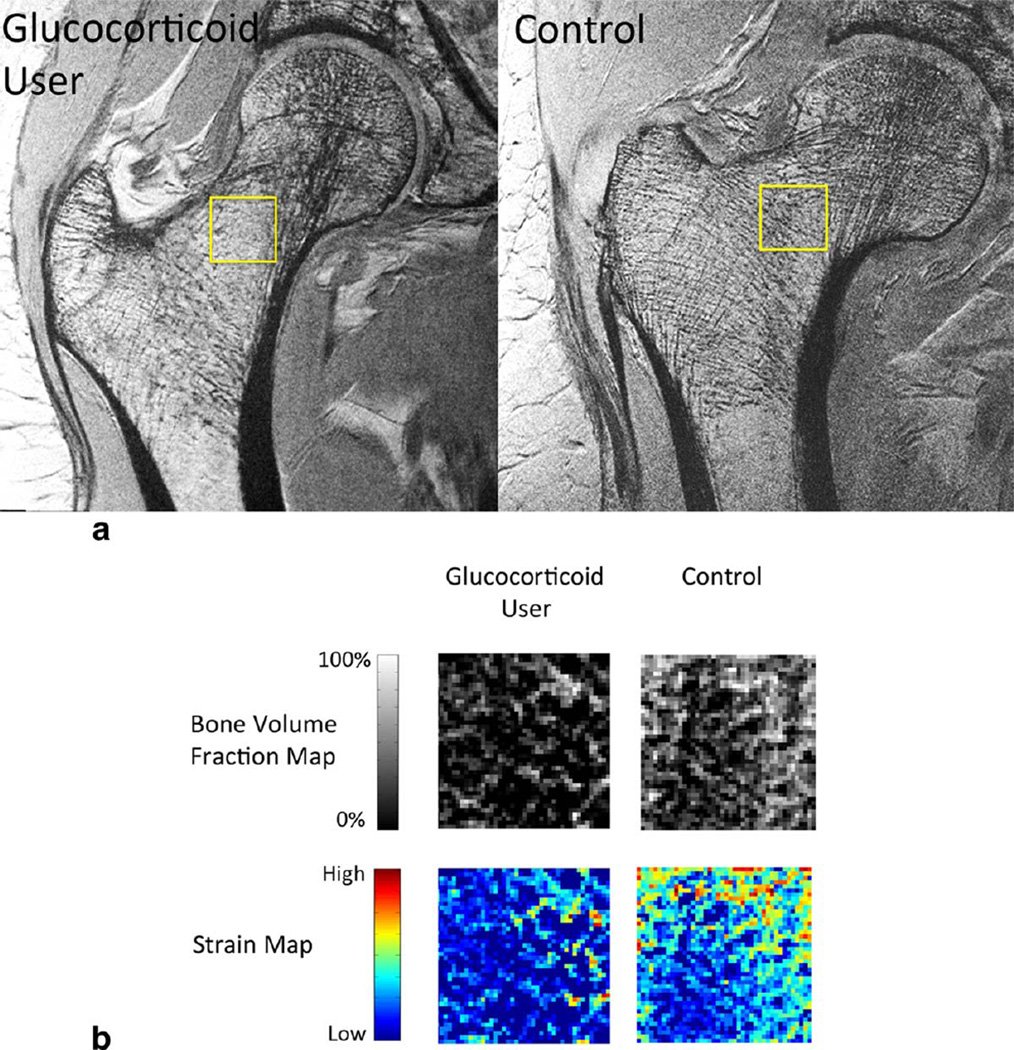

Representative proximal femur images from a subject with long-term glucocorticoid use and a healthy control are shown in Figure 1a. Representative femoral neck bone volume fraction maps and strain maps are shown in Figure 1b. There is deterioration in femoral neck microarchitecture in the glucocorticoid user compared with the control subject.

FIGURE 1.

a: Representative coronal MR images demonstrate deterioration in proximal femur microarchitecture in a glucocorticoid user compared with a control. The square highlights the region of interest within the femoral neck that was quantitatively analyzed. b: Representative femoral neck bone volume fraction maps and strain maps from a glucocorticoid user and a control. The bone volume fraction map was used to compute femoral neck trabecular thickness, separation, number, and plate-to-rod ratio. The strain map was used to compute femoral neck elastic modulus.

Compared with controls, glucocorticoid users demonstrated detrimental changes in proximal femur microarchitecture and strength, including lower median femoral neck trabecular number (−50.3%, 1.12 [IQR = 0.84 to 1.54] mm−1 versus 2.27] IQR = 1.88 to 2.73] mm−1, P = 0.02), trabecular plate-to-rod ratio (−20.1%, 1.48 [IQR = 1.39 to 1.71] versus 1.86 [IQR = 1.76 to 2.20], P = 0.03), and elastic modulus (−64.9% to −74.8%, 1.54 [IQR = 1.22 to 3.19] GPa to 2.31 [IQR = 1.87 to 4.44] GPa versus 6.15 [IQR = 5.00 to 7.09] GPa to 6.59 [IQR = 5.58 to 7.31] GPa, P<0.05). Glucocorticoid users also demonstrated higher median femoral neck trabecular separation compared with controls (+192%, 0.705 [IQR = 0.462 to 1.00] mm versus 0.241 [IQR = 0.194 to 0.327] mm, P = 0.02). There was no significant difference in femoral neck trabecular thickness between the glucocorticoid users and controls (−2.7%, 0.193 [IQR = 0.184 to 0.217] mm versus 0.199 [IQR = 0.179 to 0.210] mm, P = 0.94) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Box and whisker plots demonstrating median values with interquartile (IQR) ranges (superior and inferior borders of boxes) and 1.5 times IQR (top and bottom whiskers). a: Compared with control subjects, glucocorticoid users demonstrated detrimental changes in MRI-computed femoral neck trabecular separation, trabecular number, and plate-to-rod ratio (P < 0.05), but no differences in femoral neck trabecular thickness (P = 0.94). b: Compared with control subjects, glucocorticoid users demonstrated lower MRI-computed femoral neck bone strength, manifested by decreased femoral neck elastic modulus, regardless of the direction of loading for finite element analysis (P < 0.05).

Compared with controls, glucocorticoid users demonstrated no significant difference in median femoral neck BMD T-score compared with controls (+20.7%, −2.1 [IQR = −2.8 to −1.4] versus −2.6 [IQR = −3.3 to −2.5], P = 0.24). Median total hip BMD T-score was higher in the glucocorticoid users compared with controls (+46.8%, −1.3 [IQR = −1.7 to −1.0] versus −2.3 [IQR = −2.6 to −2.1], P = 0.002) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Box and whisker plots demonstrating median values with interquartile (IQR) ranges (superior and inferior borders of boxes) and 1.5 times IQR (top and bottom whiskers). DXA revealed no significant difference in median femoral neck BMD T-scores between the glucocorticoid users and controls (P = 0.24). Glucocorticoid users paradoxically demonstrated a higher median total hip BMD T-score compared with controls (P = 0.002). The latter is consistent with the known lack of a relationship between BMD and fracture risk in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.

We also assessed the correlation between DXA and MRI results for control subjects and glucocorticoid users. For control subjects, there was no significant correlation between femoral neck or total hip BMD T-score and any MRI parameter (Table 3, P ≥ 0.54 for all). For glucocorticoid users, there was no significant correlation between femoral neck or total hip BMD T-score and any MRI parameter (Table 4). The correlations between total hip BMD T-score and trabecular separation and number did approach significance in glucocorticoid users (Table 4; P = 0.05). However, this association was paradoxical (higher bone density correlated with higher trabecular separation and lower trabecular number).

TABLE 3.

Correlation Between DXA and MRI Parameters for Control Subjects*

| Tb.Th. (mm) |

Tb.Sp. (mm) |

Tb.N. (1/mm) |

Plate-to-rod ratio |

ESI (GPa) |

EML (GPa) |

EAP (GPa) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral Neck BMD T-Score | Correlation Coefficient | 0.26 | −0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.23 |

| p value | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.66 | |

| Total Hip BMD T-Score | Correlation Coefficient | −0.14 | −0.31 | 0.31 | 0.26 | −0.14 | −0.14 | −0.31 |

| p value | 0.78 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.54 | |

There was no significant correlation found.

BMD = bone mineral density; Tb.Th. = femoral neck trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp. = trabecular separation; Tb.N. = trabecular number; E = elastic modulus with simulated loading in three different directions: SI = superior-inferior; ML = medial-lateral AP = anterior-posterior.

TABLE 4.

Correlation between DXA and MRI Parameters for Glucococorticoid Users*

| Tb.Th. (mm) |

Tb.Sp. (mm) |

Tb.N. (1/mm) |

Plate-to-rod ratio |

ESI (GPa) |

EML (GPa) |

EAP (GPa) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral NECK BMD T-SCORE | Correlation coefficient | 0.14 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.29 | 0.029 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| P value | 0.79 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 0.78 | |

| Total HIP BMD T-SCORE | Correlation coefficient | −0.73 | 0.81 | −0.81 | −0.52 | −0.52 | −0.26 | −0.26 |

| P value | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.62 | 0.62 | |

There was no significant correlation found. There was a trend toward significance for a paradoxical correlation between total hip BMD T-score and the MRI parameters of trabecular separation and trabecular number.

BMD = bone mineral density; Tb.Th. = femoral neck trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp. = trabecular separation; Tb.N. = trabecular number; E = elastic modulus with simulated loading in three different directions: SI = superior-inferior; ML = medial-lateral AP = anterior-posterior.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that 3T MRI can detect deterioration in proximal femur microarchitecture and strength in long-term glucocorticoid users compared with controls. In keeping with the lack of a relationship between BMD and fracture risk in GIO, the glucocorticoid users in this study had similar or paradoxically slightly higher BMD compared with control subjects. The results suggest that microarchitectural deterioration contributes to skeletal fragility in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, the most common secondary form of osteoporosis.

Overall, our MRI results are consistent with those of ex vivo studies of bone microarchitecture in both animals and humans. In the early 2000s, Lill et al reported the results of a sheep model of GIO.18,19 In bone specimens obtained from sheep 6 months after the start of glucocorticoid use, microcomputed tomography scanning revealed up to 53–63% decreases in trabecular number and thickness and 150% increases in trabecular separation in glucocorticoid-injected sheep compared with controls. The authors also performed mechanical testing of these specimens and found 40–70% reductions in bone stiffness and ultimate failure load in the GIO sheep compared with controls. Dalle Carbonare et al and Chappard et al performed human, cross-sectional iliac crest biopsy studies of female20 and male21 glucocorticoid users compared with healthy, age and gender-matched controls. The investigators reported histomorphometric and microcomputed tomography results in line with the results of our study: 30–60% reductions in trabecular thickness, number, and connectivity in the glucocorticoid users compared with controls. We did not find any differences in trabecular thickness between groups in our study; this is probably due to our small sample size.

Our results are also consistent with the results of a recent in vivo high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) study of glucocorticoid users compared with controls.22 HR-pQCT is capable of imaging at 81 micron isotropic voxel size. In this study of the distal tibia, the investigators found that glucocorticoid users demonstrated deterioration in both trabecular and cortical bone microarchitecture as well as decreased whole bone stiffness compared with controls. Similar to our study, the glucocorticoid users in this HR-pQCT study did not differ from the controls in terms of areal BMD in the hip as assessed by DXA.

The control subjects in this study were older than the glucocorticoid users. This could explain why the controls had similar or slightly lower BMD than the glucocorticoid users. Indeed, for the controls, the total hip BMD T-scores were in the osteopenic range and the femoral neck BMD Tscores were in the osteoporotic range, while for the glucocorticoid users, both the total hip and femoral neck BMD T-scores were in the osteopenic range. Because the controls were older than the glucocorticoid users, we would also expect the controls to demonstrate deterioration in bone microarchitecture compared with the glucocorticoid users. But despite the controls being older than the glucocorticoid users, the glucocorticoid users were the ones who demonstrated relative micraorchitectural deterioration. Because DXA could not detect lower BMD in the glucocorticoid users compared with the controls, even though the glucocorticoid users had received greater than 12 months of steroids, the results suggest that MRI assessment of microarchitecture may potentially be more sensitive than DXA assessment of areal BMD as a method to assess changes in bone quality related to glucocorticoid use.

Most previous MRI studies of bone microarchitecture have been performed in the distal extremities (radius or tibia), but we have assessed microarchitecture in the proximal femur. Compared with the distal extremities, larger voxel sizes are needed in the proximal femur to maintain image quality. This is because signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is lower when imaging the hip, a deeper anatomic structure. Nevertheless, assessment of microarchitecture in the hip allows direct comparison with DXA, which is performed routinely in the hip as clinical standard-of-care. Because it is also possible to assess the hip using CT, it will important in the future to compare CT with MRI in terms of their ability to detect detrimental changes in bone quality secondary to glucocorticoid use.

To determine whether DXA and MRI capture the same information, we assessed the correlation between DXA results and MRI results. The lack of any significant correlation between DXA-computed BMD T-scores and MRIcomputed microarchitectural parameters in both control subjects and glucocorticoid users supports the notion that MRI provides different information about bone quality than DXA. In glucocorticoid users, there was a trend toward a significant correlation between total hip BMD T-score and both trabecular separation and number; however, this correlation was paradoxical. Specifically, higher BMD was associated with higher trabecular separation and lower trabecular number. Because animal18,19 and human20,21 biopsy studies of GIO have demonstrated that glucocorticoid use causes higher trabecular separation and lower trabecular number, this result supports the notion that DXA-assessed BMD has limitations as a method for monitoring glucocorticoid-induced changes in bone quality and fracture risk in GIO.

This study has limitations. First, the number of subjects was small. However, as an initial pilot study, we were still able to detect differences between groups. Further validation with a larger cohort, including subjects who have been exposed to glucocorticoids for shorter periods of time (< 6 months), will be necessary in the future. Second, we used a 3D FLASH sequence to acquire the MR images. This is not as SNR efficient as spin-echo or steady-state free precession sequences. However, the 3D FLASH is already available as a product sequence on MRI scanners from several vendors and is, therefore, ready for widespread use. Finally, the scan time was relatively long at 15 min, which increases the chance for motion artifact. Though we did not notice motion artifact on our images, in order for this method to be clinically translatable in the future, it will be necessary to reduce the scan time, potentially through the use of more SNR efficient pulse sequences combined with higher parallel acceleration factors (we used an acceleration factor of two in this study) or the implementation of compressed sensing.

In conclusion, we have shown that 3T MRI can detect deterioration in proximal femur microarchitecture in longterm glucocorticoid users compared with controls who do not differ by BMD. The results suggest that MRI assessment of microarchitecture may provide insight into the microarchitectural basis for skeletal fragility in GIO and that microarchitectural assessment may have possible value, beyond BMD assessment, as a tool to diagnose osteoporosis in the setting of glucocorticoid use. This is a small pilot study, and further validation with a large cohort is necessary.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: NIH; Contract grant number: K23 AR059748; Contract grant number: R01 AR066008; Contract grant number: NIH K25 AR060283.

G.C. and C.S.R. were funded by the NIH.

References

- 1.van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. The epidemiology of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:777–787. doi: 10.1007/s001980200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Abenhaim L, Zhang B, Cooper C. Use of oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:993–1000. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinbuch M, Youket TE, Cohen S. Oral glucocorticoid use is associated with an increased risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:323–328. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Staa TP, Laan RF, Barton IP, Cohen S, Reid DM, Cooper C. Bone density threshold and other predictors of vertebral fracture in patients receiving oral glucocorticoid therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3224–3229. doi: 10.1002/art.11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. A meta-analysis of prior corticosteroid use and fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:893–899. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consensus development conference: diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med. 1993;94:646–650. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90218-e. [No authors listed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet. 2002;359:1929–1936. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cushing H. The basophila adenomas of the pituitary body and their clinical manifestations (pituitary basophilism) Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1932;50:137–195. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajapakse CS, Leonard MB, Bhagat YA, Sun W, Magland JF, Wehrli FW. Micro–MR imaging–based computational biomechanics demonstrates reduction in cortical and trabecular bone strength after renal transplantation. Radiology. 2012;262:921–931. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11111044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wehrli FW. Structural and functional assessment of trabecular and cortical bone by micro magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:390–409. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saha PK, Wehrli FW, Gomberg BR. Fuzzy distance transform: theory, algorithms, and applications. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2002;86:171–190. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang G, Honig S, Brown R, et al. Finite element analysis applied to 3-T MR imaging of proximal femur microarchitecture: lower bone strength in patients with fragility fractures compared with control subjects. Radiology. 2014;272:464–474. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saha PK, Wehrli FW. Measurement of trabecular bone thickness in the limited resolution regime of in vivo MRI by fuzzy distance transform. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:53–62. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.819925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wald MJ, Magland JF, Rajapakse CS, Wehrli FW. Structural and mechanical parameters of trabecular bone estimated from in vivo high-resolution magnetic resonance images at 3 tesla field strength. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:1157–1168. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zysset PK, Guo XE, Hoffler CE, Moore KE, Goldstein SA. Elastic modulus and hardness of cortical and trabecular bone lamellae measured by nanoindentation in the human femur. J Biomech. 1999;32:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo XE, Goldstein XA. Is trabecular bone tissue different from cortical bone tissue? Forma. 1997;12:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajapakse CS, Magland JF, Wald MJ, et al. Computational biomechanics of the distal tibia from high-resolution MR and micro-CT images. Bone. 2010;47:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lill CA, Fluegel AK, Schneider E. Effect of ovariectomy, malnutrition and glucocorticoid application on bone properties in sheep: a pilot study. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:480–486. doi: 10.1007/s001980200058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lill CA, Fluegel AK, Schneider E. Sheep model for fracture treatment in osteoporotic bone: a pilot study about different induction regimens. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:559–565. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200011000-00007. discussion 565–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalle Carbonare L, Arlot ME, Chavassieux PM, Roux JP, Portero NR, Meunier PJ. Comparison of trabecular bone microarchitecture and remodeling in glucocorticoid-induced and postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:97–103. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappard C, Peyrin F, Bonnassie A, et al. Subchondral bone microarchitectural alterations in osteoarthritis: a synchrotron microcomputed tomography study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutter S, Nishiyama KK, Kepley A, et al. Abnormalities in cortical bone, trabecular plates, and stiffness in postmenopausal women treated with glucocorticoids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:4231–4240. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]