Abstract

Background: Both rising healthcare costs and the global financial crisis have fueled a search for policy tools in order to avoid unsustainable future financing of essential health benefits. The scope of essential health benefits (the range of services covered) and depth of coverage (the proportion of costs of the covered benefits that is covered publicly) are corresponding variables in determining the benefits package. We hypothesized that a more comprehensive health benefit package may increase user cost-sharing charges.

Methods: We conducted a desktop research study to assess the interrelationship between the scope of covered health benefits and the height of statutory spending in a sample of 8 European countries: Belgium, England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Scotland, Sweden, and Switzerland. We conducted a targeted literature search to identify characteristics of the healthcare systems in our sample of countries. We analyzed similarities and differences based on the dimensions of publicly financed healthcare as published by the European Observatory on Health Care Systems.

Results: We found that the scope of services is comparable and comprehensive across our sample, with only marginal differences. Cost-sharing arrangements show the most variation. In general, we found no direct interrelationship in this sample between the ranges of services covered in the health benefits package and the height of public spending on healthcare. With regard to specific services (dental care, physical therapy), we found indications of an association between coverage of services and cost-sharing arrangements. Strong variations in the volume and price of healthcare services between the 8 countries were found for services with large practice variations.

Conclusion: Although reducing the scope of the benefit package as well as increasing user charges may contribute to the financial sustainability of healthcare, variations in the volume and price of care seem to have a much larger impact on financial sustainability. Policy-makers should focus on a variety of measures within an integrated approach. There is no silver bullet for addressing the sustainability of healthcare.

Keywords: Healthcare Reform, Essential Health Benefits, Cost-Sharing

Background

Rising healthcare costs are leading to major sustainability issues in healthcare systems around the world. In addition, the global financial crisis has reduced the availability of health system resources. As a result, many European countries have implemented policy tools to address these financial challenges.1,2 In the United States, criteria for essential health benefits have been developed to cover health services that are medically effective and affordable for purchasers.3 Healthcare spending is a function of price and quantity (volume), and controlling costs therefore requires controlling the price and/or volume.4 Strategies for enhancing the financial sustainability of health systems may be aimed at reducing the demand for healthcare, reducing the supply of healthcare provisions, or controlling the price of healthcare services. However, proposed policy tools such as reducing the scope of essential services covered, reducing population coverage and user charges for essential services, risk undermining important goals of the health system, such as access and solidarity.1

The scope of essential health benefits (the range of services covered) and depth of coverage (the proportion of costs of the covered benefits that is publicly covered) are hypothesized as corresponding variables in determining the benefits package. In other words, a generous benefits package (wide range of service coverage) may correspond with high private financial contributions (low coverage depth), while a limited benefits package may correspond with high coverage depth.5,6 Understanding the potential interrelationships between these variables may help policy-makers enhance the financial sustainability of healthcare. Both a reduction in the scope of the benefits package, and an increase in user charges for health services are often advocated as (effective) means for cost control.

In an effort to safeguard the financial sustainability of publicly supported healthcare, countries have employed a variety of initiatives in redefining the benefit package. In England, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has developed a list of ‘do not do’ recommendations with the aim of excluding specific services.7 In Australia, the Comprehensive Management Framework was developed to assess health services for effectiveness, safety, and monetary value.8 In the Netherlands, there is an ongoing debate about the further establishment of rigorous evaluations of essential health benefits.9 In the United States, essential health benefits are offered under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), with latitude at the state level to define essential benefits by choosing a benchmark plan modeled on existing state plans.10,11

User charges are an often-cited policy measure for cost-containment. The RAND Health Insurance Experiment in the Unites States showed that user charges reduced the use of medical care, although this reduction was related to both inappropriate (unnecessary) and appropriate (necessary) use of care.12 User charges have the potential to reduce overuse or unnecessary care.13 As such, user charges are an attempt to better match demand and supply.14 As a response to the global financial crisis, at least sixteen countries reported introducing or increasing user charges for a variety of services.2 However, the impact of varying user charges on appropriate use of care is as yet unclear.

In this study, we hypothesized that the scope of health benefits is related to the level of user charges for covered benefits. The aim of our study was to assess the interrelationship between the scope of coverage and the financial arrangements of statutory financed healthcare in European countries. Policy-makers can use such information to further address issues relevant to enhancing financial sustainability, and for modifying essential health benefits, for example through mapping possible trade-off effects between publicly funded benefits and private contributions. We specified 2 research questions to address our objectives:

What are the scope of health benefits and the financing of statutory financed healthcare within European countries?

What is the interrelationship between the scope of health benefits and financial arrangements of statutory financed healthcare?

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a desktop research study to compare a sample of European countries with varied healthcare systems and characteristics. Our sample included 8 countries: Belgium, England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Scotland, Sweden, and Switzerland. Three of these countries (England, Scotland, and Sweden) operate a National Health Service (NHS), while 5 countries (Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland) operate a system of social health insurance (SHI). This sample shows variations in approaches to healthcare coverage, such as national vs. regional approaches, public vs. private financing, and (managed) competition vs. no competition. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the healthcare systems in these 8 countries.

Table 1. Characteristics of Healthcare Systems in the Selected 8 European Countriesa .

| BE | ENG | FR | GE | NL | SC | SWE | SWI | |

| SHI/NHS | SHI | NHS | SHI | SHI | SHI | NHS | NHS | SHI |

| National/regional | REG | REG | REG | NA | NA | REG | REG | REG |

| Benefits in kind/indemnity | B/I | B | B | B/I | B/I | B | B | B/I |

| Vertical integration | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO |

| Selective purchasing | * | * | * | ** | *** | NO | * | ** |

| Competition | * | * | * | ** | *** | * | * | *** |

| Benefits: control government | *** | *** | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | * |

| Private financing | ** | * | *** | ** | ** | * | * | *** |

Abbreviations: SHI, social health insurance; NHS, National Health Service; NA, National; REG, Regional; B, Benefits in kind – the insurer makes payments directly to the healthcare provider; I, Indemnity – the insured pays out-of-pocket and is then reimbursed by the insurer; BE, Belgium; ENG, England; FR, France; GE, Germany; NL, the Netherlands; SC, Scotland; SWE, Sweden; SWI, Switzerland.

*** = high; ** = average; * = low.

aGeneral typology based on key characteristics of healthcare systems.

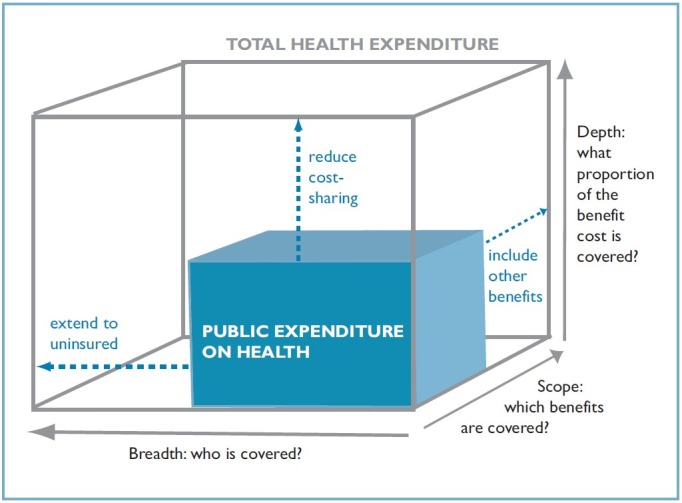

Outcomes

We developed outcomes based on the dimensions of publicly financed healthcare as published by the European Observatory on Health Care Systems. These dimensions were initially developed in the Health BASKET study,4,5 and were further specified for the series Health Systems in Transition of the Observatory.15 The 3 dimensions are: (1) population coverage, ie, the proportion of the population that is covered for healthcare; (2) service coverage, ie, the scope of healthcare benefits that are covered; and (3) cost coverage, ie, the proportion of costs that is covered for included healthcare benefits (see Figure 1). These 3 dimensions were further operationalized, resulting in indicators related to population coverage: SHI or NHS, assignment procedure, percentage of population covered; service coverage: open or closed description of benefits, main benefits in public scheme; and cost coverage: total spending, public vs. private funding, cost sharing. The focus of our study was to compare essential health benefits for curative care, thus excluding long-term care and public health services. However, the distinction between these services is not always clear-cut, and we have clarified this in the results when relevant.

Figure 1.

The Three Dimensions of Publicly Financed Healthcare.15

Literature Review

We conducted a targeted literature search to identify the main characteristics of the healthcare systems in our sample of countries. We used several data sources known for their review of healthcare systems: Health Systems in Transition of the European Observatory on Health Care Systems,16-23 International Profiles of Health Care Systems of The Commonwealth Fund,24 the Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC) of the European Union (EU),25 reports of the Civitas Health Unit,26-28 and reports of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).29,30 For quantitative comparisons, we used OECD Health Data,31 3 International Health Policy surveys of the Commonwealth Fund,32-34 and SHARE surveys.35

In addition, we conducted a targeted literature search in PubMed and Google Scholar to find both peer-reviewed publications and grey literature. We employed a wide-angle approach using combinations of the following search terms: healthcare systems, health benefits, healthcare access, governance, workforce planning, healthcare financing, public financing, private financing, healthcare costs, healthcare premiums, deductibles, co-payments – in combination with the names of the 8 countries in our sample. We also used policy documents, websites and information from key informants in our network. The literature for our data analysis was searched until December 2014.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

In comparing the sample of 8 countries, we used both qualitative and quantitative data to inform the description of the healthcare system for the specified outcomes as of the year 2013. We analyzed similarities and differences in the 3 dimensions of statutory financed healthcare systems to assess interrelationships between the comprehensiveness of health benefits and financial arrangements. In addition, we explored 2 main variables that may interact with the 3 dimensions of healthcare systems: variations in volume (use of healthcare services), and price (costs of healthcare services).

Results

Population Coverage

Five countries in our sample (Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland) operate a system of mandatory SHI for their residents. In each of these countries, population coverage is more than 99%. In the Netherlands and Switzerland, residents are required to contract with a health insurer of their own choice, based on managed competition of insurers via national and regional health exchanges, respectively.36 Residents in France are ‘assigned’ to one of the SHI companies, eg, through their employer. In Belgium and Germany, health insurance is obligatory for all citizens and permanent residents. Contrary to the Netherlands and Switzerland, German and Belgian beneficiaries in principle get household insurance. However, they are also free to choose their insurers or sickness funds, and may switch periodically.37 Residents of England, Scotland and Sweden are automatically covered through their NHS systems.

Service Coverage

Service coverage is specified in a health benefits basket that describes the publicly financed care accessible to all residents via SHI or NHS. Service coverage can be specified through 2 approaches: (a) an ‘open specification’ with a general (functional) description of benefits outlining eligibility for these benefits, and (b) ‘closed specification’ with detailed (positive) listings of all benefits that are covered through public financing.6,15 Open systems may also use negative listings of services that are not covered. Belgium and France have a closed specification system with positive listings of 7000-8500 covered benefits. Germany also uses lists of benefits, but these are less detailed and not available for the full spectrum of healthcare. England, Scotland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland use negative listings of services that are not covered. Coverage of prescriptions drugs is separately described in the 8 countries, with positive listings in 5 countries (Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland), and negative listings in 3 countries (Germany, England, Scotland).

Table 2 presents the main benefits for adults in the 8 countries of our sample. All countries cover regular medical services, and exclude cosmetic surgery. We found only small differences between the countries. Examples of such differences are related to specific services such as dental care, physical therapy, and prescription drugs. Routine dental care for adults is not covered in the Netherlands and Switzerland, while these services are covered in the other countries. In the Netherlands, primary care and physical therapy for adults is partially covered (after 20 treatment sessions) for certain chronic conditions. In Switzerland, nine treatment sessions are covered within 3 months upon referral. In England and Scotland, physical therapy is fully covered, while Belgium, Germany, France, and Sweden charge co-payments for physical therapy treatments. The limited coverage for health services may be related to potential coverage outside the curative care system. For example, in the Netherlands physical therapy services for residents in nursing homes are covered through the long-term care budget.

Table 2. Health Services for Adults Covered by Public Financinga .

| Services | BE | ENG | FR | GE | NL | SC | SWE | SWI |

| Primary care physician | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Medical specialist | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Maternal care | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hospital care | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Rehabilitation | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Prevention | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Dental care | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| Mental healthcare | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Physical therapy | Y | Y | Y | Y | Sb | Y | Y | Y |

| Occupational therapy | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Speech therapy | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Medical devices | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Cosmetic surgery | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

Abbreviations: NL, the Netherlands; BE, Belgium; GE, Germany; ENG, England; FR, France; SC, Scotland; SWE, Sweden, SWI, Switzerland; Y, Yes; N, No.

a Comparisons in this table refer to adults aged 19-60 without chronic disease or low income.

bS=Specification: Only covered for certain chronic conditions after 20 sessions.

Sources: Health Systems in Transition, European Observatory on Health Care Systems; International Profiles of Health Care Systems 2012, The Commonwealth Fund; MISSOC; WHO Medicines Documentation (http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2943e/11.3.html).

Cost Coverage

Financial data for healthcare in the 8 countries is listed in Table 3. The Netherlands has the highest relative costs of total healthcare with 11.9% of the gross domestic product (GDP), while the costs for the cure sector (ie, without long-term care and home care) in the Netherlands are, with 7.4% of GDP, the lowest in our sample. Table 3 also shows the relative costs of public vs. private funding. Private funding includes private insurance, direct payments for noncovered services, and cost-sharing for covered health services. Two main groups can be identified in comparing the shares of private funding. England, Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Scotland show a relative low percentage, ranging from 9.6% to 11.9%. The share of private funding in Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland is higher and varies from 19.5% to 25.5%.

Table 3. Financial Data (2011) .

| Costs | BE | ENG | FR | GE | NL | SC | SWE | SWI |

| Total healthcare costs as % GDP | 10.5 | 9.4 | 11.6 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 9.4 | 9.5 | 11.0 |

| Curative sector as % GDPa | 7.7 | - | 9.1 | 8.6 | 7.4 | - | 7.7 | 8.1 |

| Curative sector ($ PPP)a | 2978 | - | 3230 | 3421 | 3171 | - | 3181 | 4155 |

| Prescription drugs (% healthcare) | 15.5 | 11.4 | 15.6 | 14.1 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 12.1 | 9.4 |

| Per capita prescription drugs (€) | 630 | 374 | 641 | 632 | 479 | 374 | 474 | 530 |

| Financing of curative sectorb | ||||||||

| % Collective (government, social security) | 71.1 | 82.8 | 76.8 | 77.7 | 78.5c | 82.8 | 80.5 | 64.9 |

| % Private (OUPd, private insurance, other) | 28.9 | 17.2 | 23.3 | 22.3 | 21.5c | 17.2 | 19.5 | 35.1 |

| % Private OUPd | 25.0 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 11.7 | 11.9c | 9.9 | 19.5 | 25.5 |

Abbreviations: NL, the Netherlands; BE, Belgium; GE, Germany; ENG, England; FR, France; SC, Scotland; SWE, Sweden; SWI, Switzerland; GDP, gross domestic product; PPP, purchasing power parity; OUP, out-of-pocket.

a We defined ‘curative care’ as a combination of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) health database categories: Services of curative and rehabilitative care, medical goods and ancillary services to healthcare.

b The OECD database did not allow a breakdown in financing for curative care for England and Scotland (both United Kingdom), thus the data represents financing for a broader range of services (including long-term care and public health).

c The data for the Netherlands has been corrected because the deductibles in the OECD data did not impute as private financing.

d Following the OECD definition, out-of-pocket expenditure includes direct payments for care without insurance benefit, co-payments, co-insurance, and deductibles.

Source: OECD health data for 2011.31

Cost-sharing (user charges) for covered services via deductibles or co-payments serve as thresholds in healthcare systems by making individuals responsible for a share of the costs. Cost-sharing varies considerably between the 8 countries in our sample, as illustrated in Table 4. In 2014, the Netherlands and Switzerland were using a mandatory deductible of €360 and €250, respectively, but beneficiaries may opt for higher voluntary deductibles in exchange for lower premiums. Sweden uses a deductible of €122 for healthcare visits, €122 for prescription drugs and €333 for dental care. After these amounts, the government subsidy gradually increases up to 100% for prescription drugs and dental care. Children are waived from deductibles in these 3 countries. All countries in our sample use co-payments within the publicly financed benefits package, either in percentage of costs for services rendered (Belgium, France, Scotland, and Switzerland) and/or fixed co-payments (England, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland). All countries in our sample also provide compensation to vulnerable groups such as elderly people or those with chronic disease.

Table 4. Illustrations of Cost-Sharing Within Publicly Financed Healthcare .

| Compulsory Deductible | Cost-Sharing (Co-payments and Co-insurance Above Maximum Reimbursement) | |

| The Netherlands | €360 | ~€95 medical transportation per year |

| €69 (<16 year) and €137.6 (≥16 year) orthopedic shoes per year | ||

| €4 per hour maternity care | ||

| €20 per session with a psychologist | ||

| €32 per day for nonmedical maternity care | ||

| 25% of the costs of a dental prosthesis | ||

| €125 for prosthesis or dental implant | ||

| 25% of the price of a hearing aid | ||

| Belgium | No | 10%-40% co-payments for most services (depending on preferential reimbursement and service type) |

| Co-payments for medicines up to 80%, depending on reimbursement category and preferential | ||

| reimbursement (0%-25%-50%-60%-80%); however the co-payments are maximized in some reimbursement | ||

| categories | ||

| €40 for first hospital day; subsequently €13 per day; plus €0.62/day for medicines, €7.44 for biological | ||

| testing/stay, €6.20 for radiology and €16.40/stay | ||

| Maximum: €450-1800 depending on level of income; €10.8-13.5 per prescription drug in some | ||

| reimbursement categories | ||

| Germany | No | €5-10 for medicines |

| €10 per hospital day or day at rehabilitation center (until max 28 days) | ||

| 10% cost-sharing physiotherapy + €10 per visit | ||

| Maximum: 2% income | ||

| England | No | €10 for medicines |

| €240 for dental trajectory | ||

| Maximum: people who are not entitled to free subscriptions but expect to need more than 3 prescriptions | ||

| in 3 months may opt for a prescription prepayment certificate at the cost of £104 per year. | ||

| France | €50a | 20%-50% for different services: general practitioner, hospital, dentist, laboratory |

| Co-payments 85% for drugs according to category (0%-35%-65%-85%), depending on medical benefit and | ||

| seriousness of the pathology | ||

| Scotland | No | 80% dental costs with a maximum of €450 |

| Sweden | €122-333b | €11-22 per general practitioner visit |

| €25-35 per visit to a medical specialist | ||

| €9 per hospitalization day | ||

| Cost-sharing for paramedic care and medical devices differ between regions | ||

| Maximum: €122 for general practitioner/medical specialist, €220 for devices, €600 for drugsc | ||

| Switzerland | €250 | 10% for all services |

| €8 for hospital admission | ||

| Maximum: €570 |

Abbreviations: SHI, social health insurance; NHS, National Health Service.

a Beneficiaries pay a deductible for a range of services (medicines, doctors, ambulance, hospital), which are deducted from reimbursement and are not insurable.

b Medicines deductible €122; deductible for dental care €333.

c After the deductible amounts, the government subsidy gradually increases up to 100%. The maximum co-payment for prescribed drugs is €244 per year.

Sources: Health Systems in Transition, European Observatory on Health Care Systems; International Profiles of Health Care Systems 2012, The Commonwealth Fund; MISSOC; WHO Medicines Documentation (http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2943e/11.3.html)

Additional (Private) Insurance

All countries provide additional insurance with large differences in uptake by the population, ranging from <5% to 90% (Table 5). These differences are partly explained by the system characteristics. England, Scotland, and Sweden have a low uptake of additional insurance due to automatic coverage in their NHS system. All countries provide supplementary insurance, while 3 countries (Belgium, Germany, and France) also provide complementary insurance. Complementary insurance refers to insurance that complements coverage of insured services (co-insurance) by covering all or part of the residual costs not otherwise reimbursed. Supplementary insurance provides coverage for additional health services not at all covered as essential health benefits. We identified annual premiums for regular additional benefits ranging from €150-912. However, such premiums are not always publicly reported, and we could therefore not establish reliable estimates. Countries with compulsory deductibles (the Netherlands and Switzerland) prohibit coverage of these deductibles via co-insurance. France raises nonrefundable co-payments for consultations and services up to €50 that cannot be covered with co-insurance.

Table 5. Table 5. Additional (Private) Insurance .

| Country | % a | Type | Description |

| The Netherlands | 85.0% | Sb | Coverage of dentist, physical therapy, eyeglasses, alternative medicine |

| Belgium | 70.0% | Cc/S | Co-insurance; coverage of orthodontist, alternative medicine, private room |

| Germany | 22.0% | C/S | Co-insurance (dental care); minor benefits, access to better amenities, private room |

| England | 13.0% | S | Inpatient or day case surgery, hospital accommodation and nursing care, inpatient tests |

| France | 90.0% | C/S | Co-insurance; private room, dental care, optical care |

| Scotland | 8.5% | S | Private acute hospital care |

| Sweden | <5.0% | S | Faster access to primary care services and shorter waits for surgery |

| Switzerland | 90.0% | S | Coverage of dentist, private room, access to senior physicians, choice of hospital |

a %: percentage of citizens with additional insurance.

b S: Supplementary insurance; provides coverage for additional health services not at all covered as essential health benefits.

c C: Complementary insurance; refers to insurance that complements coverage of insured services by covering all or part of the residual costs not otherwise reimbursed.

Establishing Price and Regulating Volume

Establishing the price of healthcare services varies between countries, and can be set at the national level (Belgium, France, Scotland) or the regional level (Germany, Sweden, Switzerland), or a combination of the 2 (the Netherlands, England). In most countries, the price of healthcare services is established by (quasi)governmental agencies, except for the Netherlands and Switzerland. In the Netherlands, the price of 70% of hospital services is established via negotiations between individual insurers and individual provider organizations. In Switzerland, prices are mostly negotiated between insurer associations and providers at the regional level. Between countries, we identified differences in responsibilities at the national vs. the regional level for regulating volume. In France, while price is negotiated at the national level and approved by government, volumes are negotiated by insurers and providers; this is similar to the Netherlands. In Scotland, price is set at the national level, while volume constraints can be set by local NHS boards. Finally, in Sweden, volumes as well as prices are negotiated at the level of county councils.

Variations in Volume and Price

The actual use of healthcare services varies strongly between the 8 sample countries. Table 6 illustrates these differences for several healthcare services. These differences can be attributed to specific services that show large variations in practice. The OECD has studied such variations in practice for several procedures in various countries of our sample, showing for instance considerable variations in volume for a low-variety, sensitive condition such as total hip prosthesis.38 Prices of healthcare services also vary between the countries in our sample.39 For example, a vignette study by the World Health Organization (WHO) shows considerably higher standardized costs for stroke services in the Netherlands (€7100) in comparison with England, France and Germany’s standardized costs of ~€4000. No major differences were found for the costs of total hip surgery with ~€6800 for this subset of countries.40,41

Table 6. Illustrations of Volume of Care in the 8 European Sample Countries .

| NL | BE | GE a | FR | UK b | SWE | SWI | |

| Inpatient care discharges per 100 000 citizens per yearc | 11 646 | 16 624 | 24 417 | 18 641 | 13 709 | 16 449 | 17 055 |

| MRI-scans per 1000 citizens per year | 49.9 | 77.0 | 95.2 | 67.5 | - | - | - |

| CT scans per 1000 citizens per year | 70.7 | 178.5 | 117.1 | 154.5 | - | - | - |

| Surgical procedures per 100 000 citizens per year | |||||||

| Cataract surgery | 856.6 | 1060.1 | 168.4 | 1077.6 | 664.7 | 848.1 | 437.7 |

| Hip replacement | 215.7 | 235.6 | 285.9 | 229.5 | 180.9 | 237.9 | 292.0 |

| Coronary artery bypass | 54.4 | 70.4 | 67.6 v28.5 | 31.0 | 37.5 | 49.4 | |

| Doctor consultations per citizen per year | 6.6 | 7.4 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

| Dentist consultations per citizen per year | 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | - | 1.2 |

Abbreviations: NL, the Netherlands, BE, Belgium; GE, Germany; ENG, England; FR, France; SC, Scotland; SWE, Sweden; SWI, Switzerland.

a Additional data on the ambulatory care sector is not counted in these statistics. Additionally, only one code per procedure category per patient was counted.

b Separate data for England and Scotland is lacking.

c The number of patients that stayed in hospital at least one night.

Source: OECD Health Data 2013.31 Only the most recent data was used.

The relationship between health benefits and the financing of healthcare

In previous paragraphs, we have described the 3 dimensions of publicly financed healthcare and variations in price and volume between the countries in our study. Our comparisons showed that virtually all residents in our sample of 8 counties are covered for basic health benefits (population coverage), which corresponds with the overall aim of European healthcare systems to provide accessible healthcare for all residents.42

Our results also show that the scope of covered healthcare benefits is comparable across the countries in our sample. We found some examples of differences for coverage of dental care, physiotherapy, and prescription drugs. In assessing the financing of curative healthcare, we found a range of 7.4% to 9.1% of GDP within the sample of our selected countries. The share of public financing of curative care ranges from 64.9% to 82.8%. At the macro level, we did not identify a pattern between the scope of services covered and the height of public financing. In other words, public financing of healthcare varied considerably between countries, while differences in covered healthcare benefits are relatively small. We did find substantial differences between the countries for cost-sharing, and identified 2 main groups within our sample: low cost-sharing in England, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Scotland; and high cost-sharing in Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland. In regards to cost-sharing, we also found no clear relationship with the scope of services.

Potential Relationships at the Level of Specific Services

We also assessed the potential relationships between service coverage and financing for specific services. Our comparisons indicated that the countries differed in details of service coverage in regards to dental care, physical therapy, and prescription drugs. We therefore specifically looked at the relationships between coverage and cost-sharing of these services.

Dental Care for Adults

Dental care for adults is not covered in the benefits package of Switzerland and the Netherlands. Of the 6 other countries in our comparisons, only Germany provides full coverage. The 5 remaining countries have substantial limitations in the coverage of dental care for adults. In Belgium, co-payments are set at 25%. Adult residents in England have to pay €240 for a dental care service. In France, co-insurance varies from 30% for routine dental care up to 90% for complex services such as orthodontic care. Scotland has implemented a co-payment of 80% of the costs, with a maximum of €450. Sweden has implemented a deductible of €333 for dental care, and residents receive a subsidy of €16-32 for preventive dental services. With the exception of Germany, all countries in our sample have limited the actual coverage of dental care for adults. In the Netherlands and Switzerland, dental care for adults is not covered at all. In Belgium, England, France, Scotland, and Sweden, residents cover a substantial amount of the costs themselves. In other words, we found indications that the actual coverage for dental care is associated with cost-sharing arrangements.

Physical Therapy

In the Netherlands, physical therapy is only reimbursed for a limited range of services: pelvic therapy for incontinence (women’s health), chronic conditions after the 20th treatment session (patients pay the first 20 sessions themselves), and for inpatient services. In England and Scotland, physical therapy services are covered in the public health service, although, and due to limited availability, a substantial amount of such services are offered in the private sector where patients have to pay themselves. In Belgium, various co-payments exist depending on the specific services, and may add up to 30% of the costs. Beneficiaries in Germany are charged a co-payment of 10% plus €10 per visit. In France, the co-payment is 40%, and in certain circumstances insurance companies only provide reimbursement after they have given written permission. In Switzerland, insurance companies reimburse the first 9 treatment sessions within 3 months after referral to physical therapy services. The actual reimbursement depends on local prices. With the exception of England and Scotland, all countries in our sample have implemented limitations to service coverage or cost coverage. This suggests that the actual coverage of physical therapy services is associated with cost-sharing arrangements.

Prescription Drugs

Prescription drugs are covered in the benefits package of all countries in our sample. In the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland, prescription drugs are subject to deductibles. Beneficiaries in Switzerland are charged another 10% co-payment on top of the deductible, and Sweden has implemented co-payments ranging from 10%-50% of the costs, with a maximum of €600. In Belgium and France, co-payments can be as high as 80% and 85%, respectively. In Germany co-payment is €5-10 per prescribed drug, and in England co-payments are €10. Only residents in Scotland are not charged co-payments. This comparison shows that co-payments have been implemented in seven out of the 8 countries in our sample. We found no associations between service coverage and cost-sharing.

Discussion

At the most general level, we found no direct interrelationship between the ranges of services covered in the health benefits package, and the height of public spending on healthcare in our sample of 8 countries. By looking at specific services, we found limited associations between actual coverage of specific services and cost-sharing arrangements for these services. Access to certain specific healthcare services is either limited by the lack of actual coverage of such services, or by establishing thresholds to access via cost-sharing. Thresholds of cost-sharing can have a similar impact on the accessibility of healthcare services. Especially in countries with SHI, the uptake of additional insurance is high. Only few countries provide co-insurance for reimbursement of cost-sharing.

The data in our sample of countries shows little variation in the scope of benefits covered at the macro level. These findings are comparable with data from the United States which also showed little variation at the macro level between small group employer plans and state and federal plans, despite the relatively unregulated US market.43 An international survey to map health policy responses to the financial crisis showed that overall the statutory benefits package was not radically changed, but that some reductions were carried out, usually at the margin.1 At the macro level, it is difficult for policy-makers to completely remove services from the essential health benefits package, because many services are beneficial to certain subgroups of patients.44

The introduction or expansion of user charges is a more common policy measure at the macro level when trying to contain the cost of healthcare; many countries increased or introduced user charges for health services in response to the crisis.1 The RAND experiment already showed price elasticity between -0.17% and -0.22%, meaning that an increase of the price due to user charges leads to a reduction of the volume of care; lower income groups were more price sensitive.12 International research in a group of European countries showed that higher user charges lead to increased inequality between low and high incomes.45 The European Observatory concluded that cost sharing is unlikely to contribute to sustainability.46 If user charges are imposed, careful attention to the design of cost-sharing policy should be paid, which should be systematic and evidence-based.

Solutions for creating sustainable future financing of essential health benefits may be found at the micro level by stimulating evidence-based practice. In England, NICE has developed a list of ‘do not do’ recommendations derived from clinical practice guidelines, with the aim of excluding low-value services for certain subgroups.7 In the United States and Canada, the Choosing Wisely campaign for reducing unnecessary tests, treatment and procedures was started in 2012, and has grown into an international campaign.47 Choosing Wisely aims to promote conversations between clinicians and patients through evidence-based recommendations. These recommendations can be derived from existing clinical practice guidelines.48

Unwarranted geographical practice variation in healthcare was set on the agenda by Wennberg as an important cost driver in healthcare.49 Unwarranted practice variation is a variation in utilization that cannot be explained by variation in patient illness or patient preferences.50 A recent systematic review identified large differences in the volume of healthcare between countries, regions, hospitals as well as individual healthcare providers.51 This may be caused by potential shortfalls in 3 areas: underuse of effective care, misuse in preference-sensitive care, and overuse of supply-sensitive care. Several remedies have been described to reduce unwarranted variation, such as the implementation of clinical practice guidelines to stimulate evidence-based practice, increasing the role of patients in shared decision-making to optimize preference-sensitive care, and regulating resource capacity in the healthcare system to reduce supply-sensitive care. However, the implementation of such remedies requires more focus in health policy-making; additionally, the absence of economic incentives that reward providers for reducing unnecessary care is considered an important barrier.52

Most countries in our European sample control the price of care at the governmental level, except for the Netherlands and Switzerland, where most prices are negotiated between private insurers and provider organizations. These countries have created managed competition in their health insurance markets, which is somewhat analogous to the United States health insurance exchanges that are operated at the state and federal level. However, it is still unclear whether these mechanisms of competition will lead to reductions in the price and/or the volume of healthcare services.36

Implications for Policy

Although reducing the scope of the benefit package and increasing user charges may contribute to the financial sustainability of healthcare, variations in volume and price of care appear to have a much larger impact on financial sustainability. Our conclusions are confirmed by a recent assessment of the impact and policy implications of the economic crisis in Europe, highlighting that policy measures aimed at reducing the scope of the benefit package or increasing user charges, were only marginal.2 Moreover, countries did not report making changes to the benefits package based on evidence of cost-effectiveness.2

In addition to the continuous evaluation of essential health benefits and cost-sharing arrangements, we suggest that other measures are needed to enhance the financial sustainability of healthcare regarding the volume and price of healthcare. Further insights into practice variations and establishing mechanisms to reduce unwarranted variation may contribute to enhancing the financial sustainability of healthcare. Supply constraints may have a much larger impact on reducing the volume of care, and thus on the long-term financial sustainability of public healthcare provision than limitations in service coverage.

For US policy-makers, our comparisons of European countries are useful for informing decision-making in regard to modifying the essential health benefits package framework. Monitoring the implementation is deemed essential to determine whether states’ differing strategies are producing the coverage improvements promised by reform. Officials have to assess whether enrollees are having a difficult time obtaining needed services because of gaps in coverage or the cost of care, and they have to modify the package accordingly.53 In the US context, with differing benefit packages and cost-sharing arrangements, a careful design of additional private insurance products warrants attention in terms of guaranteeing the sustainability of healthcare.

Limitations

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, the 3 dimensions of healthcare (population coverage, service coverage, cost coverage) provide a simplification of statutory financed healthcare. The organizational and financial structure of healthcare is complex, and embedded in a wider societal structure with many more interactions. Second, due to the complexity of healthcare systems, comparisons across countries are subject to cautious interpretations. Although the dimensions of statutory financed healthcare that we used in our study are being employed in many international comparisons, such a model may not reflect the complexity of healthcare in our sample of countries. Third, our data analysis focused on the relationship between the scope of essential health benefits and statutory financing at the macro level, without disaggregating to differences at the micro level. Fourth, our sample of European countries was based on purposive sampling to reflect the variety existing in healthcare systems in Europe, and their main characteristics. Therefore, our sample does not provide a full picture of healthcare in Europe. Fifth, our study was explorative in nature, and did not allow for identifying causal relationships.

Conclusion

The scope of services covered in publicly financed healthcare is comparable and comprehensive across our sample of 8 European countries, with only marginal differences. Cost-sharing arrangements show larger variations. Considerations for the inclusion of services in the essential health benefits and for cost-sharing seem to evolve independently. However, cost-sharing implies thresholds for accessing specific health services. Both the scope of services and cost-sharing arrangements should be carefully monitored. Unwarranted practice variation and the price of healthcare services seem much larger drivers for the sustainability of healthcare. Our comparisons may not reflect the complexity of the healthcare system, and there is no silver bullet for addressing the sustainability of healthcare. Policy-makers should focus on a variety of measures within an integrated approach, including considerations for services covered, cost-sharing arrangements, additional private insurance, stimulating evidence-based practice, monitoring and reduction of unwarranted variation, and control mechanisms for the price of healthcare services. For policy-makers, our comparisons of European countries are useful for monitoring the implementation of essential health benefits, as well as to inform decision-making in regards to modifying the essential health benefits package framework.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. The sponsor did not have a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, or writing of the report.

Ethical Issues

Our desktop study did not involve human subjects and was deemed exempt from review by the ethics committee of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PvdW, JW, GW, and PJ were responsible for study concept and design. JW and PvdW were responsible for data gathering and drafting of the manuscript. PJ and GW provided important feedback to draft versions of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript

Key messages

Implications for policy makers

Reduction of the scope of the benefit package and an increase of user charges has limited impact on the reduction of the volume and cost of care at the macro level. Supply constraints may have a much larger impact on reducing the volume of care and thus the long-term financial sustainability of public healthcare provision.

Policy-makers should focus on a variety of measures within an integrated approach, including considerations for services covered, costsharing arrangements, stimulating evidence-based practice, the monitoring and reduction of unwarranted variation, and control mechanisms for the price of healthcare services.

Implications for public

Coverage for healthcare services funded by public revenues in our sample of 8 European countries is comparable and comprehensive, with only marginal differences. It is the cost-sharing arrangements for citizens that vary the most, and they imply different thresholds for individual access to specific health services in the selected countries.

Citation: van der Wees PJ, Wammes JJG, Westert GP, Jeurissen PPT. The relationship between the scope of essential health benefits and statutory financing: an international comparison across eight European countries. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(1):13–22. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.166

References

- 1. Mladovsky P, Srivastava D, Cylus J, et al. Health Policy Responses to the Financial Crisis in Europe. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2012.

- 2. Thomson S, Jowett M, Evetovits T, Jakab M, McKee M, Figueras J. Health, Health Systems and Economic Crisis in Europe: Impact and Policy Implications. Copenhagen: World Health Organization/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2013.

- 3. Ulmer C, Ball J, McGlynn E, Shadia Bel Hamdounia S. Essential Health Benefits: Balancing Coverage and Costs. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine (IOM); 2011.

- 4.Chernew ME, Newhouse JP. Health care spending growth In: Pauly MV, McGuire TG, Pedro PB, eds Handbook of Health Economics. Elsevier. 2000:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Busse R, Schreyogg J, Velasco-Garrido M. HealthBASKET: Synthesis Report. Brussels: EHMA; 2006.

- 6.Schreyogg J, Stargardt T, Velasco-Garrido M, Busse R. Defining the “Health Benefit Basket” in nine European countries Evidence from the European Union Health BASKET Project. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6(1):2–10. doi: 10.1007/s10198-005-0312-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garner S, Littlejohns P. Disinvestment from low value clinical interventions: NICEly done? BMJ. 2011;343:d4519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elshaug AG, Watt AM, Mundy L, Willis CD. Over 150 potentially low-value health care practices: an Australian study. Med J Aust. 2012;197(10):556–560. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. College voor Zorgverzekeringen (CVZ). Pakketbeheer in de praktijk deel 3 (CONCEPT). Diemen: CVZ; 2013.

- 10.Corlette S, Lucia KW, Levin M. Implementing the Affordable Care Act: choosing an essential health benefits benchmark plan. The Commonwealth Fund. 2013;15:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. HHS. Essential Health Benefits Bulletin. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight; 2011.

- 12. Frank R. Economics and mental health: an international perspective. In: Glied S, Smith P, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Health Economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011:232-233.

- 13.Chernew M. Additional reductions in Medicare spending growth will likely require shifting costs to beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(5):859–863. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith PC. Universal health coverage and user charges. Health Econ Policy Law. 2013;8(4):529–535. doi: 10.1017/s1744133113000285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rechel B, Thomson S, van Ginneken E. Health Systems in Transition: Template for Authors. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policy 2010.

- 16.Chevreul K, Durand-Zaleski I, Bahrami SB, Hernandez-Quevedo C, Mladovsky P. France: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2010;12(6):1–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busse R, Bluemel M. Germany: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2014;16(2):1–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerkens S, Merkur S. Belgium: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2010;12(5):1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyle S. United Kingdom (England): Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2011;13(1):1–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schafer W, Kroneman M, Boerma W. et al. The Netherlands: health system review H. ealth Syst Transit . 2010;12(1):1–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steel D, Cylus J. United Kingdom (Scotland): Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2012;14(9):1–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anell A, Glenngard AH, Merkur S. Sweden: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2012;14(5):1–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. European-Observatory. Health Care Systems in Transition: Switzerland. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Care Systems; 2000.

- 24. Thomson S, Osborn R, Squires D, Jun M. International profiles of Health Care Systems. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2012.

- 25. MISSOC: Mutual Information System on Social Protection website. http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=815&langId=en. Accessed December 23, 2014.

- 26. Daley C, Gubb J. Healthcare Systems: Switzerland. London: Civitas Health Unit; 2012.

- 27. Daley C, Gubb J. Healthcare Systems: The Netherlands. London: Civitas Health Unit; 2013.

- 28. Green D, Irvine B, Clark E, Bidgood E. Healthcare Systems: Germany. London: Civitas Health Unit; 2012.

- 29. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD. OECD Reviews of Health Systems - Switzerland. Paris: OECD; 2011.

- 30. Paris V, Devaux M, Wei L. Health Systems Institutional Characteristics. A survey of 29 countries, OECD Working Paper No. 50. Paris: OECD; 2010.

- 31. Health Data. OECD website. http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/oecdhealthdata.htm. Accessed December 21, 2014.

- 32.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Bishop M, Peugh J, Murukutla N. Toward higher-performance health systems: adults’ health care experiences in seven countries, 2007. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(6):w717–w734. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.w717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM, Pierson R, Applebaum S. How health insurance design affects access to care and costs, by income, in eleven countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(12):2323–2334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the United States compared to ten other countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(12):2205–2215. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. SHARE. Survey of Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe. Wave 1,2,4. In: Wave 1,2,4. Edited by SHARE. Munich: Munich Center for the Economics of Aging (MEA); 2013.

- 36.van Ginneken E, Swartz K, Van der Wees P. Health insurance exchanges in Switzerland and the Netherlands offer five key lessons for the operations of US exchanges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(4):744–752. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Ven WP, Beck K, Buchner F. et al. Preconditions for efficiency and affordability in competitive healthcare markets: are they fulfilled in Belgium, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands and Switzerland? Health Policy. 2013;109(3):226–245. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McPherson K, Gon G, Scott M. International variations in a selected number of publications, OECD Health Working Paper No. 61. Paris: OECD; 2013.

- 39.Busse R, Schreyogg J, Smith PC. Variability in healthcare treatment costs amongst nine EU countries - results from the HealthBASKET project. Health Econ. 2008;17(1 Suppl):S1–S8. doi: 10.1002/hec.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wismar M, Palm W, Figueras J, Ernst K, van Ginneken E. Cross-border health care in the European Union. Copenhagen: World Health Organization on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2011.

- 41. Mason A, Epstein D, Smith PC, et al. International comparison of costs: An exploration of within- and between-country variations for ten healthcare services in nine EU member states. York: Center for Health Economics; 2007.

- 42. European-Commission. On effective, accessible and resilient systems. In: Communication from the Commission. European-Commission, eds. Brussels: European Commission; 2014.

- 43. ASPE. Essential health benefits: comparing benefits in small group products and state and federal employee plans. Washington, DC: Office of the assistant secretary of planning and evaluation, US Department of Health; 2011.

- 44.Gress S, Niebuhr D, Rothgang H, Wasem J. Criteria and procedures for determining benefit packages in health care A comparative perspective. Health Policy. 2005;73(1):78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deveraux M, de Looper M. Income-related inequalities in health service utilization in 19 OECD countries. Health Working Papers No. 58. Paris: OECD, 2012.

- 46. Thomson S, Jowett M, Evetovits T, Jakab M, McKee M, Figueras J. Health, Health Systems and Economic Crisis in Europe: Impact and Policy Implications. Copenhagen: WHO/ European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2013.

- 47.Levinson W, Kalewaard M, Bhatia RS. et al. ‘Choosing Wisely’ a growing international campaign. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):167–174. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stretch D, Follmann M, Klemperer D. et al. When Choosing Wisely meets clinical practice guidelines. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundsheitswesen. 2014;108(10):601–603. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wennberg J, Gittelsohn. Small area variations in health care delivery. Science. 1973;182(4117):1102–1108. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4117.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wennberg JE. Tracking Medicine. A Researcher’s Quest to Understand Health Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- 51.Corallo AN, Croxford R, Goodman DC, Bryan EL, Srivastava D, Stukel TA. A systematic review of medical practice variation in OECD countries. Health Policy. 2014;114(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wennberg J. Practice variations and health care reform: connecting the dots Health Aff (Millwood) October. 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giovannelli J, Lucia KW, Sabrina C. Implementing the Affordable Care Act: revisiting the ACA’s essential health benefits requirements. The Commonw Fund. 2014;15:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]