Abstract

Objectives: To investigate whether Holotropic Breathwork™ (HB; Grof Transpersonal Training, Mill Valley, CA) has any significance in the development of self-awareness.

Design: A quasi-experiment design and multiple case studies. A single case design was replicated. The statistical design was a related within-subject and repeated-measures design (pre-during-post design).

Setting/location: The study was conducted in Denmark.

Participants: The participants (n = 20) were referred from Danish HB facilitators. Nine were novices and 11 had experience with HB.

Intervention: Four HB sessions.

Outcome measures: The novices (n = 9) underwent positive temperament changes and the experienced participants (n = 11) underwent positive changes in character. Overall, positive self-awareness changes were indicated; the participants' (n = 20) scores for persistence temperament, interpersonal problems, overly accommodating, intrusive/needy, and hostility were reduced. Changes in temperament were followed by changes in paranoid ideation scale, indicating a wary phase.

Results: Participants (n = 20) experienced reductions in their persistence temperament scores. The pretest mean (mean ± standard deviation, 114.15 ± 16.884) decreased at post-test (110.40 ± 16.481; pre–during-test p = 0.046, pre–post-test p = 0.048, pre–post-test effect size [d] = 0.2). Temperament changes were followed by an increase in paranoid ideation; the pre-test mean (47.45 ± 8.88) at post-test had increased to a higher but normal score (51.55 ± 7.864; pre–during-test p = 0.0215, pre–post-test p = 0.021, pre–post-test d = 0.5). Pre-test hostility mean (50.50 ± 10.395) decreased at post-test (47.20 ± 9.001; p = 0.0185; d = 0.3). The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems total pre-test mean (59.05 ± 17.139) was decreased at post-test (54.8 ± 12.408; p = 0.044; d = 0.2). Overly accommodating pre-test mean (56.00 ± 12.303) was decreased at post-test (51.55 ± 7.797; p = 0.0085; d = 0.4). The intrusive/needy pre-test score (57.25 ± 13.329) was decreased at post-test (52.85 ± 10.429; p = 0.005; d = 0.4).

Conclusions: The theoretical conclusion is that HB can induce very beneficial temperament changes, which can have positive effects on development of character, measured as an increase in self-awareness.

Introduction

Christina and Stanislav Grof developed Holotropic Breathwork™ (HB; Grof Transpersonal Training, Mill Valley, CA) in 1975. HB is a psychotherapeutic procedure involving hyperventilation, a voluntary, prolonged, mindful, and deep overbreathing procedure supported by music and elective bodywork. The HB session is largely nonverbal and without interventions. It concludes with mandala drawing and sharing. A typical HB session lasts for about 1–3 hours, and the client terminates the session voluntarily.1,2

The research on HB is sparse. Rhinewine and Williams3 found only three studies that appear to constitute reliable and empirical evidence. Holmes and colleagues' research was published in a peer-reviewed journal.4 Pressman's PhD thesis (1993) and Hanratty's PhD thesis (2002) are unpublished.3

The primary purpose of this pilot study was to examine empirically the therapeutic value of HB. The research question was, Does HB have any significance in the development of self-awareness, and, in that case, what kind of significance does it have?

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

The Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics for Northern Jutland, Videnskabsetiske Komite for Region Nordjylland, concluded that the project was a questionnaire and interview study rather than an interventional study and was not part of a study of biological material. Therefore, notifying the Committee on Health Research Ethics was not required. The Danish Data Protection Agency (Datatilsynet) approved the project on October 5, 2009 (reference no. 2009-41-3807). The participants gave informed consent.

Participants

All participants were referred by HB facilitators, who offered free HB sessions for this study. The facilitators advertised the research project on their website homepages, and potential participants registered their interest in the project via these homepages. Twenty participants participated (All-HB). Exclusion criteria were previous HB sessions with the researcher or contraindications for HB as specified by the HB facilitators: glaucoma, retinal detachment, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease (including heart attacks, angina, and high blood pressure), aneurysm, communicable or infectious diseases, seizure disorders, strong medication, severe mental illness, recent significant surgery or injuries, and pregnancy.1

Participants included 11 women and 9 men. Nine participants were novices (no HB experience; 0-HB group). Eleven participants had previously undergone 1–40 HB sessions, for a mean of 6.5 sessions (Exp-HB group). The participants' ages ranged from 25 to 56 years (mean age, 44.25 years). The participants' educational background was as follows: Twenty-five percent had attended vocational training or high school, 5% had undergone a short period of higher education (<3 years), 40% had 3–4 years of education, and 30% had more than 4 years of education (e.g., a Master's or PhD degree). Seven participants dropped out: Two did not complete the questionnaires on time, and five withdrew because of illness and logistic problems.

Study design

A quasi-experiment design was chosen because random assignment of participants was not possible in this field study. To make the analytical conclusions more powerful,5 the chosen method was a multiple-case study in which a single-case design was replicated. The statistical design6 was a related within-subject and repeated-measures design (pre-during-post design). Eighteen persons subsequently participated in a semi-structured interview.

Intervention

The participants (n = 20) engaged in four HB sessions, which took place during two weekend workshops separated by a 12-week interval. They underwent two HB sessions at each weekend workshop.

Measures

The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-R), validated by Cloninger, was used to find indications of significant movement in self-awareness. Implicit in Cloninger's works are measurements of self-awareness levels regarding subject-subject relations, subject-object relations, and object-object relations. TCI-R measures four types of temperaments (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence) and three character scales (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence). According to Cloninger, it is most advantageous to have average temperament scores because they are often connected to an organized character. Temperament refers to the emotional response we have automatically. High character scores indicate high self-awareness, maturity, and a well-regulated personality, which is also connected to well-being.7 The Danish TCI-R version and raw score were used.*,8

Several sources were used to raise the construct validity. To discover possible changes in the subject-object relation and identify the participants' interpersonal problems, the validated Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) was applied. The following scales describe these interpersonal difficulties: domineering/controlling, vindictive/self-centered, cold/distant, socially inhibited, nonassertive, overly accommodating, self-sacrificing, and intrusive/needy. The IIP total T score in general indicates levels of interpersonal mental distress.9

To identify changes in the object-object relation, the validated Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) was applied, measuring the extent of symptoms. SCL-90-R has the following scales: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. The Global Severity Index measures the overall psychological distress. The Positive Symptom Distress Index measures the intensity of symptoms and a Positive Symptom Total score and records the number of self-reported symptoms.10

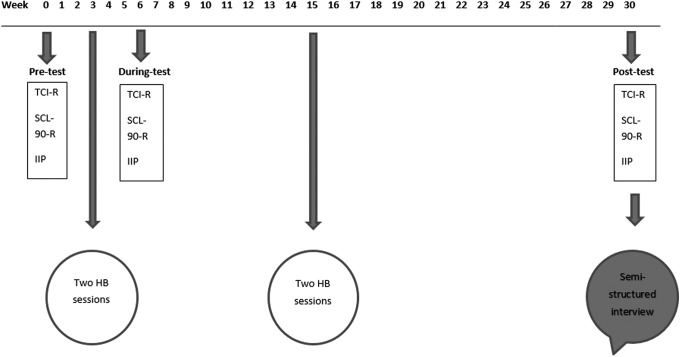

To follow the continuously nonlinear unfolding of the self-awareness phenomenon, repeated measures were used. The TCI-R, IIP, and SCL-90-R questionnaires were completed 3 weeks before the first two HB sessions (pre-test), 3 weeks after these first two HB sessions (during-test), and 15 weeks after the fourth HB session (post-test) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Time flow of the completion of the questionnaires, the Holotropic Breathwork (HB) sessions at weekend workshops, and the semi-structured interview. Questionnaires were the Temperament and Character Inventory R (TCI-R), Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R), and Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS versions 20 and 22. The repeated measure data from the TCI-R, IIP, SCL-90-R questionnaires were statistically analyzed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon T test for related samples. The test is a distribution-free test6 used at an ordinal level.

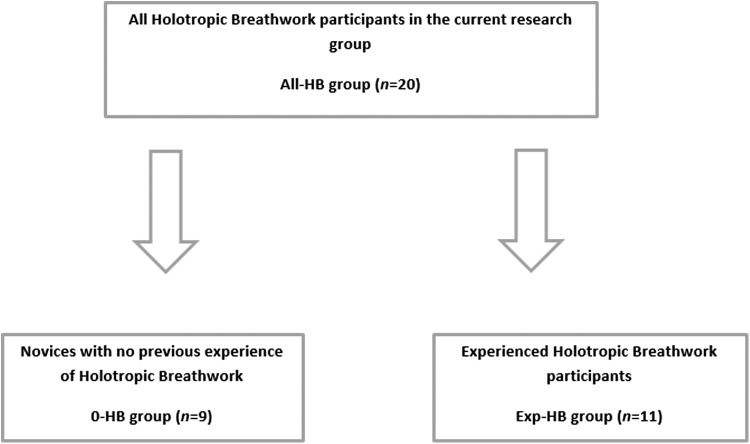

The effect size was measured using Cohen d,11 in which SD is calculated as a pooled variance estimate. Descriptive statistics were provided for age, education, and experience with HB. Results were provided for the All-HB group (n = 20), the 0-HB group (n = 9), and the Exp-HB group (n = 11) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of HB novices and more experienced HB participants.

Results

For the All-HB group (n = 20), positive changes in mean pre-post were found on 24 of 28 scales. Four scales moved within the average score range in a less favorable direction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results for All–Holotropic Breathwork Group (n = 20): Pre-During and Pre-Post Significance, Effect Size, Mean ± Standard Deviation

| p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Pre-duringa | Pre-posta | Effect size (d)bpre-post | Pre-test mean ± SD | During-test mean ± SD | Post-test mean ± SD |

| Novelty seekingc | 0.1685 | 0.2855 | 112.5 ± 10.797 | 112.95 ± 8.793 | 111.65 ± 7.896 | |

| Harm avoidancec | 0.4045 | 0.199 | 97.00 ± 16.556 | 97.05 ± 16.12 | 95.20 ± 17.57 | |

| Reward dependencec | 0.307 | 0.3435 | 106.00 ± 11.475 | 106.75 ± 11.648 | 105.00 ± 9.032 | |

| Persistencec | 0.046d | 0.048d | 0.2 small | 114.15 ± 16.884 | 111.05 ± 18.497 | 110.40 ± 16.481 |

| Self-directednessc | 0.389 | 0.3145 | 139.35 ± 22.210 | 139.65 ± 21.772 | 139.60 ± 19.011 | |

| Cooperativenessc | 0.036d | 0.5 | 143.40 ± 13.690 | 141.05 ± 13.96 | 143.30 ± 12.511 | |

| Self-transcendencec | 0.1875 | 0.07 | 84.15 ± 14.922 | 82.15 ± 16.246 | 86.55 ± 15.919 | |

| IIP totale | 0.1905 | 0.044d | 0.2 small | 59.05 ± 17.139 | 57.65 ± 15.332 | 54.80 ± 12.408 |

| Domineering/controllinge | 0.4875 | 0.086 | 55.15 ± 16.872 | 55.60 ± 14.292 | 51.40 ± 12.258 | |

| Vindictive/self-centerede | 0.2365 | 0.074 | 55.40 ± 13.751 | 54.35 ± 12.596 | 51.50 ± 9.157 | |

| Cold/distante | 0.412 | 0.0845 | 60.55 ± 17.911 | 59.80 ± 16.52 | 56.50 ± 14.036 | |

| Socially inhibitede | 0.071 | 0.3865 | 56.20 ± 12.099 | 54.65 ± 12.704 | 55.65 ± 11.245 | |

| Nonassertivee | 0.285 | 0.2455 | 57.50 ± 13.539 | 56.65 ± 11.618 | 55.95 ± 9.622 | |

| Overly accommodatinge | 0.216 | 0.0085d | 0.4 small | 56.00 ± 12.303 | 54.90 ± 12.540 | 51.55 ± 7.797 |

| Self-sacrificinge | 0.1725 | 0.229 | 52.50 ± 12.718 | 51.55 ± 10.195 | 50.50 ± 11.255 | |

| Intrusive/needye | 0.1475 | 0.005d | 0.4 small | 57.25 ± 13.329 | 55.25 ± 13.094 | 52.85 ± 10.429 |

| Global Severity Indexf | 0.4925 | 0.336 | 55.75 ± 8.422 | 55.65 ± 9.461 | 55.05 ± 8.432 | |

| Positive Symptom Distress Indexf | 0.1045 | 0.2165 | 55.75 ± 9.781 | 53.50 ± 9.902 | 53.60 ± 9.344 | |

| Positive Symptom Totalf | 0.2915 | 0.4775 | 55.85 ± 8.248 | 56.40 ± 8.419 | 55.70 ± 7.881 | |

| Somatizationf | 0.3585 | 0.468 | 53.40 ± 11.381 | 52.20 ± 11.786 | 53.50 ± 8.495 | |

| Obsessive-compulsivef | 0.343 | 0.1475 | 54.75 ± 8.397 | 53.85 ± 10.363 | 52.85 ± 10.806 | |

| Interpersonal sensitivityf | 0.3215 | 0.099 | 55.90 ± 9.130 | 56.55 ± 9.133 | 54.25 ± 9.066 | |

| Depressionf | 0.279 | 0.2995 | 57.05 ± 8.407 | 55.55 ± 10.211 | 55.85 ± 9.241 | |

| Anxietyf | 0.4475 | 0.4795 | 55.05 ± 8.876 | 54.00 ± 9.386 | 54.85 ± 8.054 | |

| Hostilityf | 0.3245 | 0.0185d | 0.3 small | 50.50 ± 10.395 | 49.85 ± 11.338 | 47.20 ± 9.001 |

| Phobic anxietyf | 0.2855 | 0.323 | 54.55 ± 11.114 | 55.05 ± 11.927 | 53.80 ± 11.228 | |

| Paranoid ideationf | 0.0215c | 0.021d | 0.5 medium | 47.45 ± 8.882 | 50.25 ± 10.857 | 51.55 ± 7.864 |

| Psychoticismf | 0.35 | 0.211 | 54.80 ± 11.919 | 55.85 ± 11.568 | 56.20 ± 9.203 | |

One-tailed.

Effect size d = (M1 − M2)/SD. SD is calculated as a pooled variance estimate:  , where n1 is pre-number, n2 is post-number, SD1 is SD pre, SD2 is SD after)).

, where n1 is pre-number, n2 is post-number, SD1 is SD pre, SD2 is SD after)).

Temperament and Character Inventory. American psychometric and normative data were provided by Robert Cloninger, MD, Thomas R. Przybeck, PhD, Dragan M. Svrakic, MD, PhD, Richard D. Wetzel, PhD (1994). The TCI scale's Cronbach was moderately to highly reliable.12 Danish TCI-R translation was provided by Ann Suhl Kristensen, PhD, and Ole Mors, PhD.*,8 Raw score was used because validity indicators were not yet available in Danish.

The difference was significant at ≤ 5%.

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) by Leonard M. Horowitz, PhD (2008). Danish edition was used, in which the IIP scale's Cronbach'sα was moderately to highly reliable.9

Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) by Leonard R. Derogatis, PhD (2009). Danish edition was used, in which the SCL-90-R scale's Cronbach'sα was moderately to highly reliable.10

SD, standard deviation.

TCI-R: significant changes for the All-HB group (n = 20)

The mean persistence temperament for the All-HB group at pre-test was close to the high score (mean ± standard deviation, 114.15 ± 16.884), and it changed at post-test toward a more beneficial score (110.40 ± 16.481). There were significant temperament changes at pre–during-test (p = 0.046) and significant changes at pre–post-test (p = 0.048), where the effect size was small (d = 0.2). Cooperativeness decreased from pre-test (143.40 ± 13.690) to during-test (141.05 ± 13.960), a significant difference (p = 0.036). At pre–during-test, but not pre–post-test, the mean returned to baseline (143.30 ± 12.511). Cooperativeness pre-during effect size was (d = 0.17).

SCL-90-R: significant changes for the all-HB group (n = 20)

For the All-HB group, the temperament changes were followed by an increase in paranoid ideation. The pre-test mean was below a T score of 50 (47.45 ± 8.882), but at post-test it had increased to a higher yet still normal score (51.55 ± 7.864). The change was significant at both pre–during-test (p = 0.0215) and pre–post-test (p = 0.021), and the effect size at pre-post was medium (d = 0.5).

For the All-HB group, hostility was average at baseline but decreased further. Mean pre-test hostility (50.50 ± 10.395) was decreased at post-test (47.20 ± 9.001). This reduction was significant (p = 0.0185), and the effect size was small (d = 0.3).

IIP: significant changes for the All-HB group (n = 20)

The total IIP pre-test mean for the All-HB group was close to the high score (59.05 ± 17.139) and at post-test had become more favorable (54.8 ± 12.408). Interpersonal problems decreased significantly (total IIP, p = 0.044), with a small effect size (d = 0.2).

The process for the All-HB group showed that the pre-test mean for overly accommodating (56.00 ± 12.303) was decreased at post-test (51.55 ± 7.797). This reduction was significant (p = 0.0085), and the effect size was small (d = 0.4).

The intrusive/needy score at pre-test was close to a high score (57.25 ± 13.329) but was decreased at post-test close to average (52.85 ± 10.429). The reduction for the All-HB group was significant (p = 0.005), with a small effect size (d = 0.4).

Investigation of significant changes for the 0-HB group (n = 9)

When the scores for the 0-HB group were extracted, the self-awareness process for these novices developed in a different direction compared with that of the experienced HB group. The 0-HB group had high pre-test temperament scores for novelty seeking (118.78 ± 8.497), reward dependence (108.00 ± 11.673), and persistence (124.00 ± 13.435). At post-test, the temperament scores were average for novelty seeking (113.56 ± 6.894) and persistence (115.11 ± 10.055). The reward dependence scores decreased toward the average but were still high (105.67 ± 7.211).

There were significant temperament changes at pre-post for novelty seeking (p = 0.0245), and the effect size was medium (d = 0.7). There was also a significant reduction in persistence (p = 0.0255), with a large effect size (d = 0.8).

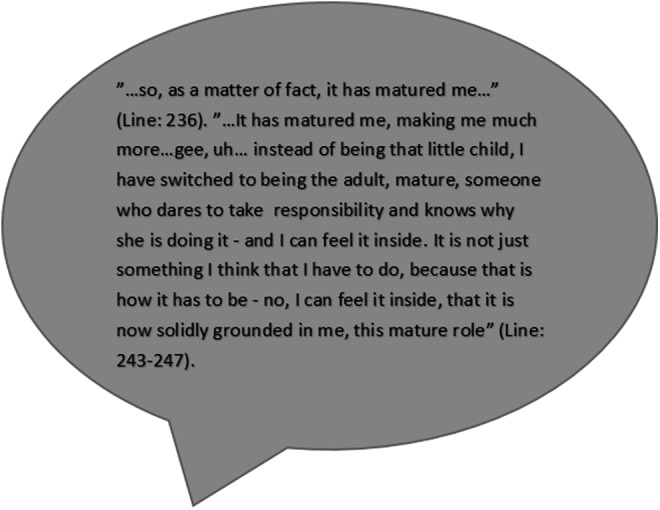

Harm avoidance was average at pre-test (97.11 ± 14.802) and was decreased at during-test (92.89 ± 15.640), a significant change (pre–during-test, p = 0.022), and the effect size was small (d = 0.3). At post-test, the mean was still within the average range and decreased even further (91.22 ± 18.559), but it was only close to significant (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

A quote from a semi-structured interview with Karen, age 54 years, no HB experience.

In general, the results for the 0-HB group indicated a new temperament baseline, which could be a more advantageous prerequisite for organized character development. The temperament changes for the 0-HB group were followed by a reduction in socially inhibited problems, wherein the pre-test T score (55.22 ± 10.269) was reduced at during-test (52.22 ± 12.397). This change was significant (pre–during-test p = 0.0455), and the effect size was small (d = 0.3). The pre–post-test difference was not significant, although the problems were reduced at post-test (53.67 ± 9.513).

The temperament change for 0-HB group is combined with an increase in paranoid ideation. At pre-test, the 0-HB group was within the normal range of paranoid ideation symptoms (45.89 ± 7.785); at post-test the symptoms were increased but were still within the normal range (52.78 ± 9.025). This change was significant (p = 0.025) and the effect size was large (d = 0.9). This finding indicates that for the 0-HB group, when medium and large changes in temperament were seen, participants were wary in this initial phase. When significant changes take place for the novices and resulted in small changes in harm avoidance at pre–during-test, the participants simultaneously reported that they had become less socially inhibited (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results for 0-HB Group (n = 9) (No Previous Holotropic Breathwork Experience): Pre-During and Pre-Post Significance, Effect Size, Mean ± Standard Deviation

| p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Pre-duringa | Pre-posta | Effect size (d)b | Pre-test mean ± SD | During-test mean ± SD | Post-test mean ± SD |

| Novelty seeking8 | 0.124 | 0.0245c | 0.7 medium | 118.78 ± 8.497 | 116.22 ± 7.362 | 113.56 ± 6.894 |

| Harm avoidance8 | 0.022c | 0.0705 | 0.3 small | 97.11 ± 14.802 | 92.89. ± 15.640 | 91.22. ± 18.559 |

| Reward dependence8 | 0.363 | 0.1865 | 108.00 ± 11.673 | 107.00 ± 10.380 | 105.67 ± 7.211 | |

| Persistence8 | 0.275 | 0.0255c | 0.8 large | 124.00 ± 13.435 | 121.11 ± 14.650 | 115.11 ± 10.055 |

| Self-directedness8 | 0.297 | 0.1175 | 138.00 ± 21.994 | 140.11 ± 21.368 | 139.78 ± 14.771 | |

| Cooperativeness8 | 0.086 | 0.096 | 145.56 ± 7.485 | 142.44 ± 9.964 | 140.56 ± 9.180 | |

| Self-transcendence8 | 0.3895 | 0.476 | 86.33 ± 13.946 | 85.33 ± 14.874 | 86.11 ± 15.862 | |

| IIP total9 | 0.075 | 0.1165 | 58.22 ± 16.415 | 56.11 ± 14.954 | 54.00 ± 9.975 | |

| Domineering/controlling9 | 0.367 | 0.457 | 55.00 ± 16.636 | 56.67 ± 16.163 | 53.33 ± 12.913 | |

| Vindictive/self-centered9 | 0.1985 | 0.305 | 53.00 ± 10.50 | 51.00 ± 9.836 | 50.67 ± 5.568 | |

| Cold/distant9 | 0.429 | 0.22 | 54.89 ± 12.937 | 54.56 ± 11.469 | 51.44 ± 8.516 | |

| Socially inhibited9 | 0.0455c | 0.3335 | 0.3 small | 55.22 ± 10.269 | 52.22 ± 12.397 | 53.67 ± 9.513 |

| Nonassertive9 | 0.088 | 0.13 | 58.33 ± 13.105 | 55.33 ± 12.600 | 54.33 ± 9.772 | |

| Overly accommodating9 | 0.146 | 0.2 | 56.33 ± 12.961 | 53.67 ± 12.981 | 53.11 ± 8.298 | |

| Self-sacrificing9 | 0.416 | 0.433 | 53.22 ± 14.898 | 53.11 ± 11.548 | 51.67 ± 11.554 | |

| Intrusive/needy9 | 0.416 | 0.103 | 58.44 ± 16.118 | 57.22 ± 15.699 | 53.78 ± 11.617 | |

| Global Severity Index10 | 0.296 | 0.5 | 54.22 ± 8.228 | 53.11 ± 7.339 | 54.33 ± 8.803 | |

| Positive Symptom Distress Index10 | 0.0705 | 0.312 | 54.78 ± 9.718 | 49.22 ± 7.412 | 51.89 ± 7.288 | |

| Positive Symptom Total10 | 0.4155 | 0.1865 | 54.67 ± 8.352 | 54.89 ± 6.679 | 55.89 ± 9.103 | |

| Somatization10 | 0.117 | 0.2875 | 54.78 ± 10.721 | 50.00 ± 9.083 | 55.00 ± 8.660 | |

| Obsessive-compulsive10 | 0.2555 | 0.363 | 53.22 ± 7.530 | 50.56 ± 9.567 | 52.00 ± 13.086 | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity10 | 0.187 | 0.2415 | 53.56 ± 8.676 | 55.00 ± 5.916 | 54.67 ± 7.566 | |

| Depression10 | 0.264 | 0.3365 | 54.67 ± 8.047 | 52.78 ± 6.610 | 52.89 ± 9.307 | |

| Anxiety10 | 0.472 | 0.4165 | 54.56 ± 8.110 | 52.33 ± 10.173 | 54.33 ± 8.617 | |

| Hostility10 | 0.3675 | 0.2995 | 49.33 ± 8.170 | 48.67 ± 10.198 | 48.33 ± 6.745 | |

| Phobic anxiety10 | 0.5 | 0.1365 | 52.11 ± 10.588 | 52.44 ± 10.956 | 54.44 ± 10.795 | |

| Paranoid ideation10 | 0.1345 | 0.025c | 0.9 large | 45.89 ± 7.785 | 48.33 ± 8.930 | 52.78 ± 9.025 |

| Psychoticism10 | 0.4325 | 0.2415 | 54.56 ± 10.248 | 52.89 ± 8.937 | 56.00 ± 8.201 | |

One-tailed.

Effect size d = (M1 − M2)/SD. SD is calculated as a pooled variance estimate:  , where n1 is pre-number, n2 is post-number, SD1 is SD pre, SD2 is SD after)).

, where n1 is pre-number, n2 is post-number, SD1 is SD pre, SD2 is SD after)).

The difference was significant at ≥ 5%.

Investigation of significant changes for the Exp-HB group (n = 11)

Temperament change was seen at pre–during-test because the novelty seeking mean for Exp-HB group at pre-test (107.36 ± 9.963) increased at during-test (110.27 ± 9.275), a score within the average range. There was a significant change in temperament at pre–during-test (p = 0.026), and the effect size was small (d = 0.3), but at post-test (110.09 ± 8.631), the change was not significant.

The persistence mean for the Exp-HB group decreased from pre-test (106.09 ± 15.443) to during-test (102.82 ± 17.685). This temperament change was significant at pre–during-test (p = 0.0495), and the effect size was small (d = 0.2). There was no significant change at pre–post-test. The mean returned to pre-test level at post-test (106.55 ± 19.972).

When temperament changes occurred for the Exp-HB group, there was a simultaneous increase in the mean paranoid ideation at pre–during-test. The pre-test mean (48.73 ± 9.870) was increased at during-test but was still within the normal range (51.82 ± 12.416); this was not a significant change but was close to significant.

The novelty seeking temperament changes for the Exp-HB group were not significant at pre–post-test, and the mean paranoid ideation decreased simultaneously at post-test (50.55 ± 7.062); however, there was no significant change at pre–post-test.

The results for the 0-HB group and the Exp-HB group indicated that as long as small, medium, and large temperament changes took place at pre–post-test, the novices experienced a new automatic emotional response. This seemed to make them more wary. The results indicated that with more HB experience the temperament change settled and the wary phase waned because there was no significant change in temperament at pre–post-test and no significant changes in paranoid ideation at pre–post-test for the Exp-HB group.

Further investigation of significant changes for the Exp-HB group (n = 11)

The Exp-HB group had no significant temperament changes at pre–post-test. Instead, the participants underwent positive character changes; the mean self transcendence score increased from pre-test (82.36 ± 16.114) to post-test (86.91 ± 16.730), and this change was significant at pre–post-test (p = 0.0225), with a small effect size (d = 0.3).

The cooperativeness mean at pre-test (141.64 ± 17.426) for the Exp-HB group also increased at post-test (145.55 ± 14.754), but this change was only close to significant (p = 0.0625) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

A quote from the semi-structured interview with Jane, age 56 years, addicted to drugs for 40 years and clean for the past 2.5. She had completed 10 HB sessions.

These results indicate higher self-awareness in both object-object relations and subject-object relations and are supported by a reduction in the Exp-HB groups domineering/controlling problems from pre-test (55.27 ± 17.872) to post-test (49.82 ± 12.082), at which point the problems were absent. This change in domineering/controlling was significant at pre–post-test (p = 0.045), and the effect size was small (d = 0.4).

The positive change in self-awareness was also supported by the reduction in the Exp-HB group's, overly accommodating problems. The mean at pre-test (55.73 ± 12.370) was reduced at post-test (50.27 ± 7.511), which was significant at pre–post-test (p = 0.0135), with a medium effect size (d = 0.6).

In addition, intrusive/needy problems decreased for the Exp-HB group, as can be seen from pre-test (56.27 ± 11.288) to post-test (52.09 ± 9.864). This reduction in intrusive/needy problems was a positive, significant change in the Exp-HB group at pre–post-test (p = 0.0055), and the effect size was small (d = 0.4).

In addition, the Exp-HB group had experienced a reduction in interpersonal sensitivity symptoms from pre-test (57.82 ± 9.443) to a more advantageous mean at post-test (53.91 ± 10.492). The change was significant at pre-post (p = 0.023), with a small effect size (d = 0.4).

Further symptom reduction supported a higher self-awareness for the Exp-HB group. The hostility pre-test mean (51.45 ± 12.234) also became a positive mean at post-test (46.27 ± 10.743), and this was a significant change at pre–post-test (p = 0.0155), with a medium effect size (d = 0.5) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results for the Experienced Holotropic Breathwork Group (n = 11): Pre-During and Pre-Post Significance, Effect Size, Mean ± Standard Deviation

| p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures (Reference) | Pre-duringa | Pre-posta | Effect size (d)b | Pre-test mean ± SD | During mean ± SD | Post-test mean ± SD |

| Novelty seeking8 | 0.026c | 0.11 | 0.3 small | 107.36 ± 9.963 | 110.27 ± 9.275 | 110.09 ± 8.631 |

| Harm avoidance8 | 0.062 | 0.3445 | 96.91 ± 18.587 | 100.45 ± 16.422 | 98.45 ± 16.884 | |

| Reward dependence8 | 0.152 | 0.4795 | 104.36 ± 11.604 | 106.55 ± 13,095 | 104.45 ± 10.615 | |

| Persistence 8 | 0.0495c | 0.4295 | 0.2 small | 106.09 ± 15.443 | 102.82 ± 17.685 | 106.55 ± 19.972 |

| Self-directedness8 | 0.439 | 0.4795 | 140.45 ± 23.394 | 139.27 ± 23.130 | 139.45 ± 22.629 | |

| Cooperativeness8 | 0.0915 | 0.0625 | 141.64 ± 17.426 | 139.91 ± 16.961 | 145.55 ± 14.754 | |

| Self-transcendence8 | 0.1635 | 0.0225c | 0.3 small | 82.36 ± 16.114 | 79.55 ± 17.546 | 86.91 ± 16.730 |

| IIP total9 | 0.453 | 0.0765 | 59.73 ± 18.478 | 58.91 ± 16.245 | 55.45 ± 14.556 | |

| Domineering/controlling9 | 0.3675 | 0.045c | 0.4 small | 55.27 ± 17.872 | 54.73 ± 13.312 | 49.82 ± 12.082 |

| Vindictive/self-centered9 | 0.428 | 0.0765 | 57.36 ± 16.176 | 57.09 ± 14.342 | 52.18 ± 11.548 | |

| Cold/distant9 | 0.36 | 0.1405 | 65.18 ± 20.571 | 64.09 ± 19.191 | 60.64 ± 16.567 | |

| Socially inhibited9 | 0.3215 | 0.4795 | 57.00 ± 13.864 | 56.64 ± 13.193 | 57.27 ± 12.705 | |

| Nonassertive9 | 0.312 | 0.383 | 56.82 ± 14.483 | 57.73 ± 11.252 | 57.27 ± 9.758 | |

| Overly accommodating9 | 0.4795 | 0.0135c | 0.6 medium | 55.73 ± 12.370 | 55.91 ± 12.708 | 50.27 ± 7.511 |

| Self-sacrificing9 | 0.155 | 0.106 | 51.91 ± 11.353 | 50.27 ± 9.318 | 49.55 ± 11.475 | |

| Intrusive/needy9 | 0.2065 | 0.0055c | 0.4 small | 56.27 ± 11.288 | 53.64 ± 11.057 | 52.09 ± 9.864 |

| Global Severity Index10 | 0.2805 | 0.224 | 57.00 ± 8.764 | 57.73 ± 10.790 | 55.64 ± 8.500 | |

| Positive Symptom Distress Index10 | 0.406 | 0.2705 | 56.55 ± 10.231 | 57.00 ± 10.602 | 55.00 ± 10.890 | |

| Positive Symptom Total10 | 0.2865 | 0.224 | 56.82 ± 8.436 | 57.64 ± 9.760 | 55.55 ± 7.188 | |

| Somatization10 | 0.193 | 0.2115 | 52.27 ± 12.289 | 54.00 ± 13.784 | 52.27 ± 8.568 | |

| Obsessive-compulsive10 | 0.4595 | 0.1525 | 56.00 ± 9.209 | 56.55 ± 10.634 | 53.55 ± 9.147 | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity10 | 0.3225 | 0.023c | 0.4 small | 57.82 ± 9.443 | 57.82 ± 11.250 | 53.91 ± 10.492 |

| Depression10 | 0.4645 | 0.3605 | 59.00 ± 8.556 | 57.82 ± 12.270 | 58.27 ± 8.867 | |

| Anxiety10 | 0.4795 | 0.305 | 55.45 ± 9.832 | 55.36 ± 8.947 | 55.27 ± 7.964 | |

| Hostility10 | 0.3115 | 0.0155c | 0.5 medium | 51.45 ± 12.234 | 50.82 ± 12.600 | 46.27 ± 10.743 |

| Phobic anxiety10 | 0.246 | 0.084 | 56.55 ± 11.631 | 57.18 ± 12.774 | 53.27 ± 12.067 | |

| Paranoid ideation10 | 0.051 | 0.1865 | 48.73 ± 9.870 | 51.82 ± 12.416 | 50.55 ± 7.062 | |

| Psychoticism10 | 0.1725 | 0.337 | 55.00 ± 13.631 | 58.27 ± 13.267 | 56.36 ± 10.347 | |

One-tailed.

Effect size d = (M1 − M2)/SD. SD is calculated as a pooled variance estimate:  , where n1 is pre-number, n2 is post-number, SD1 is SD pre, SD2 is SD after.

, where n1 is pre-number, n2 is post-number, SD1 is SD pre, SD2 is SD after.

The difference was significant at minimum 5%.

Discussion

For the All-HB group (n = 20), significant temperament changes were seen for persistence. This indicates a movement toward a temperament that, according to Cloninger,7 is connected to a lower risk of obsessional tendencies, which can make it easier to handle contingency events. The All-HB group experienced a significant reduction in interpersonal problems and IIP total score, which indicates that participants became more sociable and experienced less interpersonal mental distress in general.

The study results show that the self-awareness process for the nine novices primarily led to significant positive medium and large changes in temperament at pre-post.

The results for the more HB-experienced group primarily show character changes because there were positive significant changes at pre–post-test on the character scale self-transcendence. The positive self-awareness changes were supported by a significant reduction in interpersonal problems, such as domineering/controlling, overly accommodating, intrusive needy, interpersonal sensitivity, and hostility symptoms.

This finding suggests that novices with high temperament scores may be prepared to undergo major positive changes in their automatic emotional responses when they start practicing HB. The results indicate that the self-awareness process, with more HB experience, continues in a positive direction toward a significant positive character development and higher self-awareness, as measured with the self-transcendence scale. According to Cloninger,7 an increase in self-transcendence indicates that people become more sensible, idealistic, transpersonal, faithful, flexible, self-forgetful, and creative with a higher spiritual awareness. The increase in self-transcendence indicates that participants have become more wise and patient and that they experience more equanimity. It also reflects that participants find it easier to let go of conflicts and struggles about control and being controlled.

HB can induce profound positive temperament changes, which may call for a redefinition of character and the way one directs one's intentions. In this phase, where temperament changes take place, it may cause participants to become more wary because their automatic reactions are new. For the novices, this indicates profound beneficial changes in temperament as they move from a high score on novelty seeking and persistence to an average score, which can decrease the risk of immaturity. An average temperament score is, according to Cloninger,7 connected to a lower risk of immaturity. Cloninger describes temperament as developmentally stable with increasing age, pharmacotherapy, and psychotherapy,7 which makes these results remarkable.

The study is based on typical conditions for HB practice. However, the study has several limitations. The sample size was small; with regard to the multiple comparisons of the 0-HB and Exp-HB groups, this is especially a limitation. The participants were volunteers who already had an interest in HB. The volunteers might have had significantly different characteristics than the norm.6 Moreover, the study's participants were not randomly selected, and the study results cannot be generalized to a larger population because there is a bias compared to the composition of the general population. The external validity is low because the sample is not representative; thus, according to Yin,5 it is only appropriate to use the findings to make analytical generalizations. Several validated questionnaires sources were used to raise the construct validity, and they were handled reliably using case study protocol and databases. With regard to the statistical procedure for the present sample, the internal validity is high.

The theoretical conclusion is that HB can induce significantly large beneficial temperament changes, which was the case for the group of novices with high persistence temperament scores. For the novice group, HB significantly reduced high temperament score on novelty seeking, which is connected to a lower risk of immaturity. The biggest temperament changes can simultaneously be followed by a significantly more wary phase because the participant's automatic response is new.

For the group with more HB experience, a significant increase in self-transcendence score was found, which indicates a higher self-awareness. For the experienced group, this is supported by a significant reduction in overly accommodating, intrusive/needy, domineering/controlling problems, and hostility and interpersonal sensitivity symptoms.

The four HB sessions significantly reduced the whole group's (n = 20) scores with regard to persistence, hostility, and interpersonal problems, including overly accommodating problems and intrusive/needy problems. The temperament change was followed by a wary phase. HB practice can provide a more organized character development measured as progression in the development of self-awareness.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Christina and Stanislav Grof, who developed HB, and to HB facilitators Jorgen Fjord Christensen, MD, Susan Kirsten Brunsgaard, and Thomas Korsgaard Kristensen, who made this project possible by providing the free HB sessions they offered from 2009 to 2013. The authors are particularly grateful to the 20 participants who made this article possible and would like to thank the members of the Danish HB Association (Holotropiforeningen) for the debate and encouragement. An international research study on a larger scale is desirable to confirm or refute this pilot study. This would be feasible thanks to Cloninger, Horowitz, and Derogatis, who have made the TCI-R, IIP, and SCL-90-R instruments available in several countries.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Kristensen AS and Mors O. TCI-R, Center for Psykiatrisk Grundforskning, Aarhus Universitetshospital. September 2004.

Kristensen AS and Mors O. TCI-R, Center for Psykiatrisk Grundforskning, Aarhus Universitetshospital. September 2004.

References

- 1.Grof S. The Adventure of Self-Discovery. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grof S. Psychology of the Future: Lessons from Modern Consciousness Research. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhinewine JP, Williams O. Holotropic Breathwork: the potential role of a prolonged, voluntary hyperventilation procedure as an adjunct to psychotherapy. J Altern Complement Med 2007;13:771–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes SW, Morris R, Clance PR, Putney RT. Holotropic breathwork: An experiential approach to psychotherapy. Psychother Theor Res Pract Train 1996;33:114–120 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Inc., 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coolican H. Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology. 4th ed. London: Routledge, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cloninger CR. Feeling Good: The Science of Well-Being. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristensen AS. Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ), Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI og TCI-R). In: Elsass P, Ivanouw J, Mortensen EL, Poulsen S, Rosenbaum B, eds. Assessmentmetoder. Copenhagen, Denmark: Dansk Psykologisk Forlag, 2006:329–351 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horowitz LM. IIP: Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. Copenhagen, Denmark: Dansk Psykologisk Forlag, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-R, Danish translation. Bloomington, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen JA. Power Primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloninger RC, Przybeck RR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A Guide to Its Development and Use. St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine Center for Psychobiology of Personality, 1994 [Google Scholar]