Abstract

Aims

In symptomatic patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD), computed tomographic angiography (CTA) improves patient selection for invasive coronary angiography (ICA) compared with functional testing. The impact of measuring fractional flow reserve by CTA (FFRCT) is unknown.

Methods and results

At 11 sites, 584 patients with new onset chest pain were prospectively assigned to receive either usual testing (n = 287) or CTA/FFRCT (n = 297). Test interpretation and care decisions were made by the clinical care team. The primary endpoint was the percentage of those with planned ICA in whom no significant obstructive CAD (no stenosis ≥50% by core laboratory quantitative analysis or invasive FFR < 0.80) was found at ICA within 90 days. Secondary endpoints including death, myocardial infarction, and unplanned revascularization were independently and blindly adjudicated. Subjects averaged 61 ± 11 years of age, 40% were female, and the mean pre-test probability of obstructive CAD was 49 ± 17%. Among those with intended ICA (FFRCT-guided = 193; usual care = 187), no obstructive CAD was found at ICA in 24 (12%) in the CTA/FFRCT arm and 137 (73%) in the usual care arm (risk difference 61%, 95% confidence interval 53–69, P< 0.0001), with similar mean cumulative radiation exposure (9.9 vs. 9.4 mSv, P = 0.20). Invasive coronary angiography was cancelled in 61% after receiving CTA/FFRCT results. Among those with intended non-invasive testing, the rates of finding no obstructive CAD at ICA were 13% (CTA/FFRCT) and 6% (usual care; P = 0.95). Clinical event rates within 90 days were low in usual care and CTA/FFRCT arms.

Conclusions

Computed tomographic angiography/fractional flow reserve by CTA was a feasible and safe alternative to ICA and was associated with a significantly lower rate of invasive angiography showing no obstructive CAD.

Keywords: Angina, Coronary computed tomographic angiography, Fractional flow reserve, Non-invasive testing

See page 3368 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv534)

Introduction

Stable chest pain is a common clinical presentation that often requires further investigation using non-invasive or invasive testing.1 The goals of testing include clarifying the diagnosis, documenting the presence or absence of coronary artery disease (CAD), and directing subsequent care, whether revascularization, intensified medical treatment, or both, while maximizing efficiency and patient safety.2 The recently completed PROMISE3 and SCOT-HEART4 trials suggest that an evaluation strategy based on coronary computed tomographic angiography (CTA) increases diagnostic certainty, improves efficiency of triage to invasive catheterization, and may reduce radiation exposure when compared with functional stress testing, with similar rates of cardiac events. Moreover, in PROMISE, CTA increased the rate of invasive catheterization by almost 50% compared with functional testing, and over a quarter of these patients did not have obstructive CAD identified by invasive angiography. Since CTA provided only anatomic information and invasive fractional flow reserve (FFR) was rarely used, revascularizations guided by a CTA strategy were generally performed without evidence of the functional significance of coronary stenoses, at variance with practice guidelines.5 This is an important consideration since CTA in PROMISE doubled the rate of coronary revascularization compared with functional testing.

A diagnostic strategy that provides both anatomic and functional data could address this limitation and potentially afford enhanced efficiency and safety. Recently, a non-invasive method to determine the haemodynamic significance of coronary stenoses has been developed that computes the fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography (FFRCT) based on computational fluid dynamics and simulated maximal coronary hyperaemia.6 Fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography has been validated against invasively measured FFR as a reference standard,7–9 but there are no data on the clinical utility of this new method and how its use may affect patient care and clinical outcomes.

The present study was designed to test the hypotheses that patients with suspected CAD evaluated using a CTA/FFRCT-guided strategy would have fewer invasive angiograms that showed no obstructive CAD than would patients who were evaluated based on standard practice, and would have similar and low rates of major cardiac events.

Methods

Study design

PLATFORM is a prospective, consecutive cohort study utilizing a comparative effectiveness observational design (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01943903).10 The study was conducted with fidelity to the protocol (see Supplementary material online). Local or central institutional review boards approved the study at the 11 enrolling European sites and at Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI); all subjects provided written informed consent.

Study participants

PLATFORM subjects were symptomatic outpatients ≥18 years old without known CAD, but with an intermediate likelihood of obstructive CAD, whose physician had planned non-emergent, non-invasive, or invasive cardiovascular testing to evaluate suspected CAD. Exclusion criteria were (i) acute coronary syndrome or clinical instability, (ii) previously documented CAD, (iii) contraindications to CTA, and (iv) needed emergent or urgent procedure. Additional exclusion criteria included recent cardiovascular testing (<90 days) (see Supplementary material online, Table S1 for full inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Study procedures

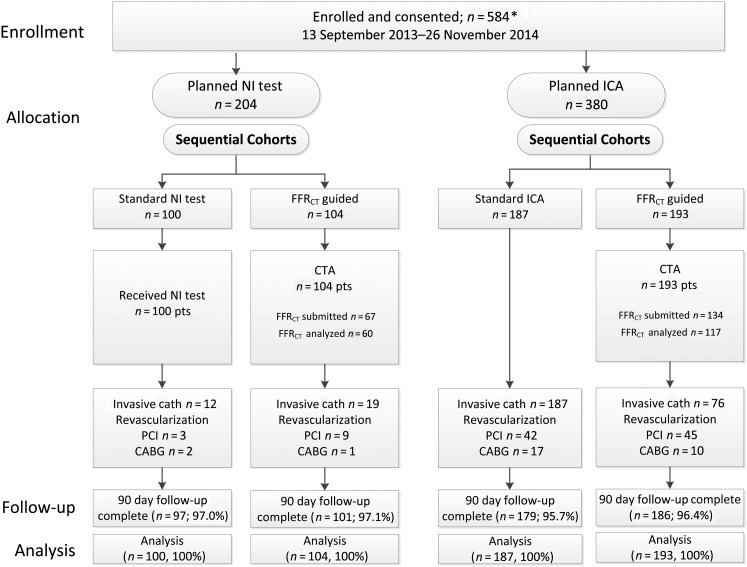

Subjects were enrolled in two consecutive cohorts assigned to receive the planned usual care testing or CTA/FFRCT testing. All sites enrolled patients into both cohorts, and each site had to complete enrolment of the planned number of usual care subjects before enrolling any CTA/FFRCT subjects. Each cohort was subdivided into two groups based on the evaluation plan decided upon before enrolment in the study: non-invasive testing (any form of stress testing or CTA without FFRCT) or invasive coronary angiography (ICA) (Figure 1). For balance, no centre could enrol >30 subjects in either planned non-invasive group or >145 subjects in the trial.

Figure 1.

Enrolment, allocation, and follow-up of the study patients. NI, non-invasive; ICA, invasive coronary angiography; FFRCT, computation of fractional flow reserve from coronary computed tomographic angiography data; CTA, computed tomographic angiography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting. *One subject withdrew consent for use of any of his/her data. In keeping with relevant national law, this subject is not included in any data listing or analysis.

In the CTA/FFRCT cohort, all subjects underwent CTA instead of the planned non-invasive or invasive evaluation. Fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography analyses were performed centrally when requested by the site (recommended if the CTA revealed ≥30% stenosis or if the patient was referred to ICA).

Optimal medical therapy was encouraged in all groups, and local physicians made all subsequent clinical decisions following standard practice,2 including cancelling or ordering additional testing or procedures. Follow-up visits were performed at 90 days, 6 months, and 12 months from study entry. Enrolment began on 10 September 2013 and was completed on 26 November 2014. There were no major protocol amendments. This article reports 90-day clinical results.

Diagnostic non-invasive and invasive testing

All usual care testing, including CTA, was performed and interpreted locally according to standard practices at the enrolling site. All CTAs utilized a ≥64-slice multi-detector, single- or dual-source CT scanner and followed scanning protocols satisfying Society of Cardiac Computed Tomography quality standards.11 An independent angiographic core laboratory (DCRI) performed all quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) measurements using QAngio software (Medis, the Netherlands) according to standard procedures.12,13

Fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography analysis was performed centrally (HeartFlow) as previously described.6–8 Briefly, three-dimensional blood flow simulations in the coronary vasculature were performed using proprietary software, with quantitative image quality analysis, image segmentation, and physiological modelling using computational fluid dynamics. Coronary blood flow was simulated under conditions that modelled intravenous adenosine to mirror pressure and flow data and the FFR numeric values that would have been obtained during an invasive evaluation. Data provided to the clinical site included the lowest FFRCT numeric value in each coronary distribution, and colour-scale representations of the coronary tree showing FFRCT values in all vessels >1.8 mm in diameter (see Supplementary material online for a sample FFRCT report).

Effectiveness and safety endpoints

The primary endpoint was the rate of ICA within 90 days that showed no obstructive CAD in patients who had invasive testing planned before enrolment, comparing those receiving usual care to those allocated to CTA/FFRCT. Obstructive disease was defined as either (i) an invasively measured FFR ≤ 0.80 in any segment, regardless of degree of stenosis, or (ii) QCA stenosis ≥50% in a vessel ≥2.0 mm diameter without an invasively measured FFR > 0.80 in the same distribution (see Supplementary material online, Table S2 for endpoint definitions). A secondary endpoint was the comparison of the rate of ICA with no obstructive CAD in those with planned non-invasive testing. The major safety endpoint was a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at 90 days: all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), and unplanned hospitalization for chest pain leading to urgent revascularization. An independent clinical events committee (DCRI) adjudicated all MACE in a blinded fashion based on standard, prospectively determined definitions.14

Cumulative radiation exposure within 90 days of study entry included all cardiovascular tests and invasive procedures, including CTA, myocardial perfusion imaging, and ICA. Radiation exposure for study CTAs was calculated from dose length product measured in mGY × cm using the formula mSv = (dose length product) × 0.014, or was imputed using the median measured value; other exposures were imputed using standard published doses of 7 mSv for ICA, 15 mSv for percutaneous coronary intervention, and 14 mSv for myocardial perfusion imaging.15

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint (rate of ICA showing no obstructive CAD in patients with invasive testing planned prior to enrolment) was compared between the usual care invasive testing vs. CTA/FFRCT-guided care arms. The risk difference and 95% confidence interval (CI) were determined, and a one-sided Wald test (α error = 0.025) for a risk difference <0 was used to evaluate whether CTA/FFRCT was superior to usual testing. Enrolment of 380 subjects in the planned invasive care arm (190 usual care and 190 CTA/FFRCT guided) was estimated to provide the study with 90% power to detect a 50% reduction in the frequency of ICA documenting non-obstructive CAD at a one-sided 0.025 level of significance, assuming an event rate of 30% in the usual care arm and 15% in the CTA/FFRCT-guided arm, and a dropout rate of 10%.

All statistical assessments were independently confirmed by DCRI. All analyses were performed comparing patients as allocated, either in aggregate or within the planned non-invasive or invasive test groups. Exceptions to this include four additional analyses of the primary endpoint: (i) reanalysis in propensity score matched subpopulations of subjects using age, sex, diabetes, smoking status, and type of angina (see below); (ii) assessment in pre-specified subgroups: age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, pre-test probability of obstructive CAD (updated Diamond and Forrester score),16 and country of enrolment; (iii) acceptable image quality population excluding subjects in the CTA/FFRCT arm with unavailable or uninterpretable CTA images; and (iv) best practices per protocol analysis as determined by independent central adjudication, excluding those CTA/FFRCT subjects who underwent ICA but for whom CTA/FFRCT did not support the need for ICA and those who did not undergo ICA but for whom CTA/FFRCT did support the need for ICA.

Baseline characteristics were summarized and compared across usual care and CTA/FFRCT-guided care cohorts. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and were compared using Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables are presented as counts (percentages) and were compared using the Pearson χ2 test, or with Fisher's exact test if cell frequencies were not sufficient. The level of statistical significance was set to 0.0025 using the Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Although extensive analysis of baseline characteristics indicated no significant differences between the cohorts, since group assignment was not randomized, a sensitivity analysis of the primary endpoint was performed using propensity score matching (see Supplemental material online for propensity scoring methods used). The propensity score was estimated based on age, sex, diabetes, smoking status, and type of angina using multivariable logistic regression, and subjects were matched using a greedy algorithm.17

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC, USA), and a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, unless otherwise specified. No interim analyses were performed.

Results

Study population

The study population (Figure 1) consisted of 584 enrolled and consented patients followed for 90 days. Complete 12-month follow-up is planned; 90-day data were obtained in 563 subjects (96.4%).

Baseline characteristics

Patient age averaged 60.9 years and 231 (39.6%) were women (Table 1). Diabetes was present in 13.7%, hypertension in 54.3%, history of smoking in 53.9%, and dyslipidaemia in 34.8% (Table 1). Typical chest pain was the presenting symptom in 123 (21.1%) and atypical pain in 435 (74.5%). The mean pre-test probability of obstructive CAD was 49 ± 17%. All baseline characteristics were similar between the usual care and FFRCT-guided care cohorts and within the planned non-invasive and invasive test groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants, according to study group

| Variable | Planned non-invasive test (N = 204) |

Planned invasive test (N = 380) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care strategy (n = 100) | FFRCT-guided strategy (n = 104) | P-value | Usual care strategy (n = 187) | FFRCT-guided strategy (n = 193) | P-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 57.9 ± 10.7 | 59.5 ± 9.3 | 0.25 | 63.4 ± 10.9 | 60.7 ± 10.2 | 0.02 |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 34 (34.0) | 44 (42.3) | 0.22 | 79 (42.2) | 74 (38.3) | 0.44 |

| Racial/ethnic minority (self-reported), no. (%) | 5 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.06 | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.60 |

| Cardiac risk factors | ||||||

| BMI, mean ± SD (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 3.0 | 27.3 ± 3.9 | 0.01 | 27.2 ± 3.8 | 27.1 ± 3.9 | 0.62 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 38 (38.0) | 57 (54.8) | 0.02 | 111 (59.4) | 111 (57.5) | 0.72 |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 8 (8.0) | 6 (5.8) | 0.52 | 36 (19.3) | 30 (15.5) | 0.33 |

| Dyslipidaemia, no. (%) | 22 (22.0) | 28 (26.9) | 0.49 | 76 (40.6) | 77 (39.9) | 0.81 |

| Current or past tobacco use, no. (%) | 52 (52.0) | 59 (56.7) | 0.50 | 103 (55.1) | 101 (52.3) | 0.59 |

| Mean number of risk factors ± SDa | 1.2 ± 0.93 | 1.4 ± 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.7 ± 1.02 | 1.7 ± 1.09 | 0.41 |

| Pre-test probability of obstructive CAD ± SDb (%) | 44.5 ± 15.3 | 45.3 ± 16.8 | 0.89 | 51.7 ± 16.7 | 49.4 ± 17.2 | 0.26 |

| Relevant medications, no. (%) | ||||||

| Aspirin | 29 (29.0) | 45 (43.3) | 0.039 | 115 (61.5) | 90 (46.6) | 0.004 |

| Statin | 24 (24.0) | 29 (27.9) | 0.58 | 83 (44.4) | 77 (39.9) | 0.37 |

| Anginal type, no. (%) | 0.018 | 0.09 | ||||

| Typical angina | 8 (8.0) | 18 (17.3) | 52 (27.8) | 45 (23.3) | ||

| Atypical angina | 91 (91.0) | 80 (76.9) | 122 (65.2) | 142 (73.6) | ||

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 1 (1.0) | 6 (5.8) | 13 (7.0) | 5 (2.6) | ||

BMI, body mass index (weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres); CAD, coronary artery disease; CT, computed tomographic angiography; SD, standard deviation.

aIncludes hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and tobacco use.

bMean pre-test probability of obstructive CAD ± SD calculated by updated Diamond and Forrester score.16

Allocation and testing

Among the 204 participants who had a non-invasive test planned for cardiac evaluation, 100 were allocated to usual care (Figure 1). The non-invasive tests performed are listed in Supplementary material online, Table S3. One hundred and four patients were allocated to CTA/FFRCT, and 39 patients (37.5%) had at least one site interpreted stenosis ≥50%. Fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography was requested in 67 patients (64.4%), but was not completed in 7 (10.4%), due to poor image quality or inadequate acquisition.

Among the 380 participants who had an invasive catheterization (ICA) planned, 187 were allocated to and received ICA (usual care) and 193 patients were allocated to and received a CTA/FFRCT; 118 patients (61%) had a stenosis ≥50%. Fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography was requested in 134 (69.4%) but was not completed in 17 (12.7%). Overall, there was one reported adverse event from CTA testing, a mild contrast reaction.

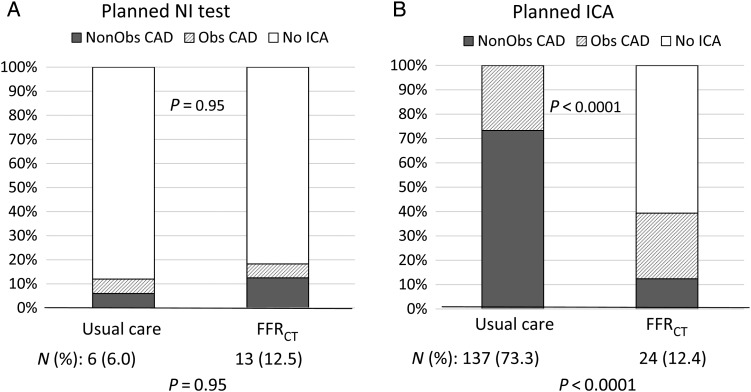

Outcome measures

Rates of ICA and findings of no obstructive disease by QCA and/or FFR in the planned non-invasive testing group are shown in Table 2. There was no difference in the secondary endpoint of the cohort rate of ICA which did not show obstructive CAD according to QCA: 6.0% usual care vs. 12.5% CTA/FFRCT; P = 0.95 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ninety-day outcomes according to study group

| Planned non-invasive test (n = 204) |

Planned invasive test (n = 380) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care strategy (n = 100) | FFRCT-guided strategy (n = 104) | P-value | Usual care strategy (n = 187) | FFRCT-guided strategy (n = 193) | P-value | |

| Invasive catheterization without obstructive CAD by core lab quantitative coronary angiography | ||||||

| No. (%) | 6 (6.0) | 13 (12.5) | 0.95 | 137 (73.3) | 24 (12.4) | <0.0001 |

| Risk difference, % (95% CI) | −6.5 (−14.4 to 1.4) | 60.8 (53.0–68.7) | ||||

| Invasive catheterization without obstructive CAD by site interpretation | ||||||

| No. (%) | 5 (5.0) | 8 (7.7) | 0.79 | 106 (56.7) | 18 (9.3) | <0.0001 |

| Risk difference (95% CI) | −2.7 (−9.4 to 4.0) | 47.4 (39.2–55.6) | ||||

| Secondary endpoint composite, MACE, no. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.0) | ||

| All-cause death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Non-fatal MI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Hospitalization with urgent revascularization | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | ||

| MACE or vascular complications, no. (%) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.1) | 7 (3.6) | ||

| Cumulative radiation exposure (enrolment to 90 days) | 0.0002 | 0.20 | ||||

| Mean ± SD (mSv) | 5.8 ± 7.1 | 8.8 ± 9.9 | 9.4 ± 4.9 | 9.9 ± 8.7 | ||

| Median (IQR) (mSv) | 2.3 (0–9.3) | 3.9 (2.4–11.6) | 7.0 (7.0–7.0) | 7.9 (2.6–16.3) | ||

CAD, coronary artery disease; CTA, computed tomographic angiography; MI, myocardial infarction; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; CI, confidence interval; IQR, inter-quartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Among patients in the planned invasive testing groups, 187 patients (100%) underwent an ICA within 90 days in the usual care cohort, and 137 (73.3%) catheterizations did not show obstructive disease by QCA and/or FFR (Figure 2, Table 2). In the CTA/FFRCT cohort, 76 (39.4%) underwent ICA, with 24 (31.6%) catheterizations showing no obstructive CAD. The primary endpoint of the rate of ICA which did not show obstructive CAD in the planned invasive testing group was found in substantially more subjects in the usual care arm at 137 (73.3%) of 187 compared with 24 (12.4%) of 193 in the CTA/FFRCT arm (risk difference 60.8%, 95% CI 53.0–68.7%, P < 0.0001). Propensity score matching resulted in inclusion of 148 patients in each group and yielded similar results (72% usual care vs. 12% CTA/FFRCT, P < 0.0001; see Supplementary material online, Table S4), as did analysis of acceptable CTA image quality (CAD was not found in 11.4% of the CTA/FFRCT arm), and a best practices/per protocol analysis (obstructive CAD was not found in 7.2%). Results were also similar in all subgroups examined (see Supplementary material online, Table S5).

Figure 2.

Determination of the rate of invasive catheterization without obstructive coronary artery disease. NI, non-invasive; ICA, invasive coronary angiography; Obs CAD, obstructive coronary artery disease; FFRCT, computation of fractional flow reserve from coronary computed tomographic angiography data.

Only two MACE events occurred in the planned ICA group assigned to CTA/FFRCT-guided care. One was a peri-procedural MI in a subject whose CTA was of insufficient quality for FFRCT analysis, and the other was hospitalization for urgent revascularization following a CTA/FFRCT showing severe CAD. There were no events in the 61% of CTA/FFRCT patients in whom ICA was cancelled. Vascular complications were similarly rare (Table 2). Rates of MACE and vascular complications were too low to assess non-inferiority.

Cumulative radiation exposure in patients with an intended non-invasive evaluation is shown in Table 2. In patients with an intended invasive evaluation, cumulative radiation exposure to 90 days was similar in the usual care cohort (9.4 mSv) and the CTA/FFRCT cohort (9.9 mSv, P = 0.2). Across both CTA/FFRCT cohorts, CTA radiation averaged 5.2 ± 5.4 mSv (9.0 ± 6.7 mSv for retrospective scans, 3.0 ± 1.6 mSv for prospectively gated scans).

There were no differences in rates of revascularization in subjects allocated to CTA/FFRCT vs. usual care in either the planned non-invasive or planned invasive testing arms; P = 0.29 and 0.58.

Information available for invasive catheterization and revascularization

In subjects in the planned non-invasive group proceeding to ICA or revascularization, there were no differences between the two arms in the proportion with functional data available (see Supplementary material online, Table S6).

In subjects in the planned invasive group proceeding to ICA, functional information was available in 83 of the 187 (44.4%) usual care subjects compared with 74 of 76 (97.4%) in the CTA/FFRCT group; P < 0.0001. Among those proceeding to revascularization, functional information was available in 30 of 59 (50.8%) in the usual care cohort vs. 53 of 55 (96.3%) patients in the CTA/FFRCT; P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Current guidelines recommend that stable chest pain patients be evaluated with non-invasive stress testing, yet the rates of invasive angiograms showing no obstructive CAD remain high.18,19 The PLATFORM study showed that, in patients with planned ICA, a diagnostic strategy based on CTA/FFRCT yielded a significantly lower rate of ICA showing no obstructive CAD. In patients with planned non-invasive testing, there was no difference between use of CTA/FFRCT and usual care. Clinical events through 90 days were rare with either strategy.

The goals of the diagnostic evaluation of patients with stable chest pain include identifying those individuals needing catheterization as well as those who cannot benefit, and providing optimal guidance for subsequent care. Two recent trials provide evidence that non-invasive visualization of the coronary arteries using CTA enhances diagnostic certainty and appropriately alters diagnostic and therapeutic plans, with comparable clinical outcomes.3,4 However, CTA increased the rate of referral to ICA and revascularization by up to 50%.3 Because the use of adjunctive invasive measures such as FFR to assess haemodynamic significance was rare, in keeping with current practice,20 a CTA-only strategy resulted in revascularization with little understanding of the ischaemia-producing potential of coronary lesions, as recommended for appropriate revascularization and optimal outcomes.5,21,22 Our data demonstrate that it is possible to obtain both anatomic and functional information non-invasively, and that doing so reduces the rate of finding no obstructive CAD at catheterization among those with planned ICA.

The low adverse clinical event rate in PLATFORM is similar to recent trials3,4 and indicates that studies of non-invasive testing in a contemporary chest pain population should, in addition to clinical events, consider use of endpoints such as changes in care plans, efficiency of diagnosis, and quality of information guiding care. To this end, the remarkable reduction in the primary endpoint of not finding obstructive CAD at ICA, and the lower overall rate of ICA, coupled with the higher rate of revascularizations informed by haemodynamic significance or ischaemia, suggest that use of CTA/FFRCT more effectively triages patients for invasive procedures than usual care strategies.

The rate of finding no obstructive CAD in our usual care ICA patients was high, but was determined by core laboratory QCA. The corresponding rate using site visual readings was lower (57%), identical to population studies19,20 reporting that 54–62% of elective catheterizations do not have obstructive disease. The higher rate by QCA is consistent with known differences between the two assessment techniques.23

Although FFRCT is a relatively new technique, PLATFORM demonstrates that it is feasible and safe in busy clinical settings. Overall, 90% of CTAs had acceptable image quality for analysis, and radiation averaged 5.2 ± 5.4 mSv, less than the average level of 14 mSv noted in the literature for nuclear stress testing.15 Use of FFRCT improved the availability of functional data available in those referred to ICA (96% CTA/FFRCT vs. 45% usual care), and those referred to revascularization (95% CTA/FFRCT vs. 55% usual care), allowing compliance with current recommendations supporting use of both anatomic and functional data in decision-making.5 While still high, the rate of revascularization performed without functional data in usual care patients is improved from previous reports of 55%.24

PLATFORM adds substantially to both the PROMISE and SCOT-HEART trials.3,4 Compared with PROMISE, the addition of FFRCT functional information in PLATFORM to the anatomic CTA information prevented the reported ∼50% increase in catheterizations and revascularizations. PLATFORM builds on SCOT-HEART's finding of increased diagnostic certainty with CTA by noting cancellation of ICA in 61% of the CTA/FFRCT arm and a dramatically lower rate of finding no obstructive CAD. Like these studies, PLATFORM provides prospective data essential to evaluating and optimizing the role of non-invasive testing as a gatekeeper to catheterization.

While PLATFORM has many strengths, it is important to note that the sample size and follow-up duration are insufficient to detect an impact on clinical outcomes. Although not randomized, PLATFORM differs substantially from most observational studies by requiring a carefully controlled ‘experimental’ intervention in the CTA/FFRCT groups, and core lab angiographic reading. The study's rigour is further enhanced by basing all analyses on the prospective allocation of patients into cohorts regardless of actual care. Use of an initial roll-in group of usual care ‘control’ patients provided a detailed, real-time snapshot of contemporaneous practice at enrolling centres, rather than using historical controls. Even in a randomized trial it would have been impossible to blind investigators to the results of testing since they are needed for clinicians to determine downstream care. Further, the current approach reflects clinical research trends favouring pragmatic design and effectiveness (vs. efficacy) evaluations. The multiple sensitivity analyses of the primary endpoint, yielding similar results, document that our findings are robust and free of significant verification bias.

In conclusion, when used as an alternative diagnostic strategy to guide care in those with planned invasive catheterization, CTA/FFRCT was associated with a significantly lower rate of angiography showing no obstructive CAD.

Authors' contributions

K.C., D.C., A.W., and F.W.: performed statistical analysis. P.S.D., G.P., M.A.H., M.R.P., B.L.N., C.R., and B.D.B.: handled funding and supervision. G.P., B.L.N., R.A.B., N.C., I.P., M.G., G.R., U.H., H.W.S., G.F., M.G., D.A., J.M.J., and M.H.: acquired the data. P.S.D., G.P., M.A.H., M.R.P., B.L.N., C.R., and B.D.B.: conceived and designed the research. P.S.D.: drafted the manuscript. P.S.D., G.P., M.A.H., M.R.P., K.C., D.C., A.W., C.R., and B.D.B.: made critical revision of the manuscript for key intellectual content.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

This work was supported by HeartFlow, Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA. Duke Clinical Research Institute independently performed QCA, adjudicated clinical events, and verified the primary and secondary endpoint determinations. There were no data confidentiality agreements. An Executive Committee oversaw trial design and study conduct, final data review, and presentation and publication of results, independently making the decision to publish. The investigators independently drafted the manuscript and take full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of data analyses.

Conflict of interest: P.S.D. has received grants from HeartFlow during the conduct of the study and other support from GE Medical Systems outside the submitted work; M.A.H. has received grants from HeartFlow during the conduct of the study; M.R.P. has received grants from HeartFlow during the conduct of the study, and grants from Jansen, Johnson & Johnson, Astra Zeneca, NHLBI, and AHRQ, and personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, and Otsuka outside the submitted work; R.A.B. has received grants from HeartFlow during the conduct of the study and personal fees from B. Braun, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific outside the submitted work; N.C. has received grants from Boston Scientific and Medtronic, and grants and personal fees from HeartFlow, Haemonectics, and St Jude Medical outside the submitted work; G.R. has received grants from HeartFlow during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Saint Jude Medical and Boston Scientific outside the submitted work; D.A. has received grants and personal fees from GE Healthcare, outside the submitted work; M.H. has received grants from Siemens Healthcare outside the submitted work; K.C. has received support from HeartFlow during the conduct of the study; F.W. and C.R. have received personal fees and other support from HeartFlow during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work; B.D.B. has received grants from Abbott, St. Jude Medical, and Medtronic, and other support from St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, Opsens, Omega Pharma, Siemens, Edwards, GE, Sanofi, HeartFlow, and Bayer outside the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in the PLATFORM trial and Auben Debus, Peter Hoffmann, Judith Jaeger, and Beth Martinez for their contributions to the study.

Appendix

PLATFORM trial organization

Sites, principal/site investigators, and staff

Milan, Italy: Principal Investigator: Gianluca Pontone; Site Investigators: Antonio Bartorelli, Daniele Andreini, Maurio Pepi, Francesco Alamanni; Staff: Erika Bertella, Saima Mushtaq, Virginia Beltrama, Andrea Baggiano; Aarhus, Denmark: Principal Investigator: Bjarne Norgaard; Site Investigators: Sara Gaur, Jesper Moller Jensen; Staff: Lone Romby, Jette R Broderson, Lene Hjelm; Munich, Germany: Principal Investigator: Robert Byrne; Site Investigators: Elena Guerra, Oliver Husser, Tobias Koppara, Jonathan Nadjiri, Martin Hadamitzky, Janina Winogradow, Janika Repp, Severin Weigand, Fritz Wimbaur, Raphazza Lohaus, Philipp Montz Rumpf, Elke Lorenz; Staff: Gisela Schoemig, Karin Hosl, Judith Ruf, Marco Valenski Ines Zenullahi; Southampton, UK: Principal Investigator: Nick Curzen; Site Investigators: James Shambrook, Simon Corbett, Iain Simpson, Alison Calver, James Wilkinson; Staff: Zoe Nicholas, Judith Ann Radmore, Bryony Tyrell, Claire Elridge, Rayner Lacoste; Newcastle, UK: Principal Investigator: Ian Purcell, Site Investigators: Rajiv Das, Iftikhar Haq, Azfar Ghaus Zaman, I Spyridopoulos, Alan Bagnall, J Ahmed; Staff: Alla Narytnyk, Jennifer Adams-Hall, Leslie Bremner, Susan Hetherington, Sarah Lamb, Angela Phillipson, Rebecca Wilson, Kathryn Procter, Samantha Jones, Victoria Andrianna Richardson, Louise Quinn, Vera Wealleans, Sarah Rowling, Chris Price; Leipzig, Germany: Principal Investigator: Matthias Gutberlet, Site Investigators: Lukas Lehmkuhl, Michael Woinke, Gerhard Schuler, Daniel Urban, Christian Lücke; Staff: Fabian Juhrich, Kathrin Luderer, Jacqueline Fohlisch, Carola Dohnert; Lyon, France: Principal Investigator: Gilles Rioufol; Site Investigators: Gérard Finet, Philippe Douek; Staff: Yvonne Varillon, Delphine Laval, Adeline Mansuy, Pauline Renaudin, Muriel Rageade; Mainz, Germany: Principal Investigator: Ulrich Hink; Site Investigators: Karl Kreitner, Alexander Jabs, Yang Yang, Tommaso Gori; Staff: Bärbel Kaesberger; Graz, Austria: Principal Investigator: Herwig Schuchlenz; Site Investigators: Dieter Botegal, Martin Genger, Peter Zechner, Wolfgang Weihs, Peter Kullnig, Walter Kau; Staff: Stefan Weikl; Innsbruck, Austria: Principal Investigator: Gudrun Feuchtner; Site Investigator: Guy Friedrich; Staff: Fabian Plank; Brest, France: Principal Investigator: Martine Gilard, Site Investigators: Jacques Boschat, Philippe Castellant, Romain Didier; Staff: Françoise Martin.

Executive committee

Pamela S. Douglas, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC, USA

Bernard De Bruyne, OLV Hospital, Aalst, Cardiovascular Centre, Aalst, Belgium

Mark Hlatky, Stanford University, Department of Health Research and Policy, Stanford, CA, USA

B.L. Norgaard, Aarhus University Hospital Aarhus Skejby, Denmark

Manesh Patel, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC, USA

Gianluca Pontone, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, IRCCS, Milan, Italy

Campbell Rogers, HeartFlow, Redwood City, CA, USA

Clinical events committee

Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC, USA

Manesh Patel, Christopher Fordyce, Joni O'Briant

Quantitative coronary angiography laboratory

Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC, USA

Manesh Patel, W. Schuyler Jones, Rohan Shah, Gary Dunn, Alicia Lowe

Clinical operations

Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC, USA

Beth Martinez

HeartFlow, Redwood City, CA, USA

Auben Debus, Judi Jaeger, Furong Wang, Alan Wilk

Contributor Information

Collaborators: On Behalf of the PLATFORM Investigators, Antonio Bartorelli, Daniele Andreini, Maurio Pepi, Erika Bertella, Saima Mushtaq, Virginia Beltrama, Andrea Baggiano, Sara Gaur, Lone Romby, Jette R Broderson, Lene Hjelm, Robert Byrne, Elena Guerra, Oliver Husser, Tobias Koppara, Jonathan Nadjiri, Martin Hadamitzky, Janina Winogradow, Janika Repp, Severin Weigand, Fritz Wimbaur, Raphazza Lohaus, Philipp Montz Rumpf, Elke Lorenz, Gisela Schoemig, Karin Hosl, Judith Ruf, Nick Curzen, James Shambrook, Simon Corbett, Iain Simpson, Alison Calver, James Wilkinson, Zoe Nicholas, Judith Ann Radmore, Bryony Tyrell, Claire Elridge, Rayner Lacoste, Ian Purcell, Rajiv Das, Iftikhar Haq, Azfar Ghaus Zaman, I Spyridopoulos, Alan Bagnall, J Ahmed, Alla Narytnyk, Jennifer Adams-Hall, Leslie Bremner, Susan Hetherington, Sarah Lamb, Angela Phillipson, Rebecca Wilson, Kathryn Procter, Samantha Jones, Victoria Andrianna Richardson, Louise Quinn, Vera Wealleans, Sarah Rowling, Chris Price, Matthias Gutberlet, Lukas Lehmkuhl, Michael Woinke, Gerhard Schuler, Daniel Urban, Christian Lücke, Fabian Juhrich, Kathrin Luderer, Jacqueline Fohlisch, Carola Dohnert, Gilles Rioufol, Gérard Finet, Philippe Douek, Yvonne Varillon, Delphine Laval, Adeline Mansuy, Pauline Renaudin, Muriel Rageade, Ulrich Hink, Karl Kreitner, Alexander Jabs, Yang Yang, Tommaso Gori, Bärbel Kaesberger, Herwig Schuchlenz, Dieter Botegal, Martin Genger, Peter Zechner, Wolfgang Weihs, Peter Kullnig, Walter Kau, Stefan Weikl, Gudrun Feuchtner, Guy Friedrich, Fabian Plank, Martine Gilard, Jacques Boschat, Philippe Castellant, Romain Didier, Françoise Martin, Pamela S. Douglas, Bernard De Bruyne, Mark Hlatky, B.L. Norgaard, Manesh Patel, Gianluca Pontone, Campbell Rogers, Manesh Patel, Manesh Patel, W. Schuyler Jones, Rohan Shah, Gary Dunn, Alicia Lowe, Beth Martinez, Auben Debus, Judi Jaeger, Furong Wang, and Alan Wilk

References

- 1.Ladapo JA, Blecker S, Douglas PS. Physician decision-making and trends in the use of cardiac stress testing in the United States: an analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:482–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabaté M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Knuuti J, Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Erol C, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Hasdai D, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kolh P, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Maggioni AP, Piepoli MF, Pries AR, Romeo F, Rydén L, Simoons ML, Sirnes PA, Steg PG, Timmis A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Yildirir A, Zamorano JL. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines; Document Reviewers. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, Mark DB, Al-Khalidi HR, Cavanaugh B, Cole J, Dolor RJ, Fordyce CB, Huang M, Khan MA, Kosinski AS, Krucoff MW, Malhotra V, Picard MH, Udelson JE, Velazquez EJ, Yow E, Cooper LS, Lee KL; PROMISE Investigators. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1291–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newby DE on behalf of the SCOT-HEART Investigators. CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet 2015;385:2383–2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, Chambers CE, Ellis SG, Guyton RA, Hollenberg SM, Khot UN, Lange RA, Mauri L, Mehran R, Moussa ID, Mukherjee D, Nallamothu BK, Ting HH. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:e44–e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor CA, Fonte TA, Min JK. Computational fluid dynamics applied to cardiac computed tomography for non-invasive quantification of fractional flow reserve: scientific basis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2233–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koo BK, Erglis A, Doh JH, Daniels DV, Jegere S, Kim HS, Dunning A, DeFrance T, Lansky A, Leipsic J, Min JK. Diagnosis of ischemia-causing coronary stenoses by non-invasive fractional flow reserve computed from coronary computed tomographic angiograms. Results from the prospective multicenter DISCOVER-FLOW (Diagnosis of Ischemia-Causing Stenoses Obtained via Noninvasive Fractional Flow Reserve) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1989–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ, Berman DS, Koo BK, van Mieghem C, Erglis A, Lin FY, Dunning AM, Apruzzese P, Budoff MJ, Cole JH, Jaffer FA, Leon MB, Malpeso J, Mancini GB, Park SJ, Schwartz RS, Shaw LJ, Mauri L. Diagnostic accuracy of fractional flow reserve from anatomic CT angiography. J Am Med Assoc 2012;308:1237–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nørgaard BL, Leipsic J, Gaur S, Seneviratne S, Ko BS, Ito H, Jensen JM, Mauri L, De Bruyne B, Bezerra H, Osawa K, Marwan M, Naber C, Erglis A, Park SJ, Christiansen EH, Kaltoft A, Lassen JF, Bøtker HE, Achenbach S; NXT Trial Study Group. Diagnostic performance of non-invasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial (Analysis of Coronary Blood Flow Using CT Angiography: Next Steps). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1145–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pontone G, Patel MR, Hlatky MA, Chiswell K, Andreini D, Norgaard BL, Byrne RA, Curzen N, Purcell I, Gutberlet M, Rioufol G, Hink U, Schuchlenz HW, Feuchtner G, Gilard M, De Bruyne B, Rogers C, Douglas PS. Rationale and design of the PLATFORM (prospective longitudinal trial of FFRCT: outcome and resource impacts) study: design of the PLATFORM study. Am Heart J 2015. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Cury R, Earls JP, Mancini GJ, Nieman K, Pontone G, Raff GL. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2014;8:342–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuinenburg JC, Janssen JP, Kooistra R, Koning G, Corral MD, Lansky AJ, Reiber JH. Clinical validation of the new T- and Y-shape models for the quantitative analysis of coronary bifurcations: an interobserver variability study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2013;81:E225–E236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiber JH, Kooijman CJ, Slager CJ, Gerbrands JJ, Schuurbiers JC, Den Boer A, Wijns W, Serruys PW, Hugenholtz PG. Coronary artery dimensions from cineangiograms methodology and validation of a computer-assisted analysis procedure. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1984;3:131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, Chaitman BR, Cutlip DE, Farb A, Fonarow GC, Jacobs JP, Jaff MR, Lichtman JH, Limacher MC, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, Nissen SE, Smith EE, Targum SL. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:403–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerber TC, Carr JJ, Arai AE, Dixon RL, Ferrari VA, Gomes AS, Heller GV, McCollough CH, McNitt-Gray MF, Mettler FA, Mieres JH, Morin RL, Yester MV. Ionizing radiation in cardiac imaging: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiac Imaging of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention of the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and intervention. Circulation 2009;119:1056–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Alkadhi H, Leschka S, Desbiolles L, Nieman K, Galema TW, Meijboom WB, Mollet NR, de Feyter PJ, Cademartiri F, Maffei E, Dewey M, Zimmermann E, Laule M, Pugliese F, Barbagallo R, Sinitsyn V, Bogaert J, Goetschalckx K, Schoepf UJ, Rowe GW, Schuijf JD, Bax JJ, de Graaf FR, Knuuti J, Kajander S, van Mieghem CA, Meijs MF, Cramer MJ, Gopalan D, Feuchtner G, Friedrich G, Krestin GP, Hunink MG; CAD Consortium. A clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: validation, updating, and extension. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1316–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 1985;39:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, Brennan JM, Redberg RF, Anderson HV, Brindis RG, Douglas PS. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med 2010;362:886–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel MR, Dai D, Hernandez AF, Douglas PS, Messenger J, Garratt KN, Maddox TM, Peterson ED, Roe MT. Prevalence and predictors of non-obstructive coronary artery disease identified with coronary angiography in contemporary clinical practice. Am Heart J 2014;167:846–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toth GG, Toth B, Johnson NP, De Vroey F, Di Serafino L, Pyxaras S, Rusinaru D, Di Gioia G, Pellicano M, Barbato E, Van Mieghem C, Heyndrickx GR, De Bruyne B, Wijns W. Revascularization decisions in patients with stable angina and intermediate lesions: results of the International Survey on Interventional Strategy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van't Veer M, Klauss V, Manoharan G, Engstrøm T, Oldroyd KG, Ver Lee PN, MacCarthy PA, Fearon WF; FAME Study Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med 2009;360:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Bruyne B, Fearon WF, Pijls NH, Barbato E, Tonino P, Piroth Z, Jagic N, Mobius-Winckler S, Rioufol G, Witt N, Kala P, MacCarthy P, Engström T, Oldroyd K, Mavromatis K, Manoharan G, Verlee P, Frobert O, Curzen N, Johnson JB, Limacher A, Nüesch E, Jüni P; FAME 2 Trial Investigators. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI for stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1208–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Lansky AJ, Cohen DJ, Jones PG, Kureshi F, Dehmer GJ, Drozda JP, Jr, Walsh MN, Brush JE, Jr, Koenig GC, Waites TF, Gantt DS, Kichura G, Chazal RA, O'Brien PK, Valentine CM, Rumsfeld JS, Reiber JH, Elmore JG, Krumholz RA, Weaver WD, Krumholz HM. Comparison of clinical interpretation with visual assessment and quantitative coronary angiography in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in contemporary practice: the Assessing Angiography (A2) project. Circulation 2013;127:1793–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin GA, Dudley RA, Lucas FL, Malenka DJ, Vittinghoff E, Redberg RF. Frequency of stress testing to document ischemia prior to elective percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Med Assoc 2008;300:1765–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]