Abstract

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R) are a family of ubiquitous, ER localized, tetrameric Ca2+ release channels. There are 3 subtypes of the IP3Rs (R1, R2, R3), encoded by 3 distinct genes, that share ~60-70% sequence identity. The diversity of Ca2+ signals generated by IP3Rs is thought to be largely the result of differential tissue expression, intracellular localization and subtype-specific regulation of the three subtypes by various cellular factors, most significantly InsP3, Ca2+ and ATP. However, largely unexplored is the notion of additional signal diversity arising from the assembly of both homo and heterotetrameric InsP3Rs. In the present article, we review the biochemical and functional evidence supporting the existence of homo and heterotetrameric populations of InsP3Rs. In addition, we consider a strategy that utilizes genetically concatenated InsP3Rs to study the functional characteristics of heterotetramers with unequivocally defined composition. This approach reveals that the overall properties of IP3R are not necessarily simply a blend of the constituent monomers but that specific subtypes appear to dominate the overall characteristics of the tetramer. It is envisioned that the ability to generate tetramers with defined wild type and mutant subunits will be useful in probing fundamental questions relating to IP3R structure and function.

Introduction

Dynamic changes in intracellular Ca2+ control a vast array of cellular processes, including muscle contraction, secretion of fluid and protein, gene transcription, metabolism and cell fate [1-5]. Although multiple Ca2+ dependent processes often operate simultaneously within the same cell, the activation of a specific process is accomplished with precision and fidelity, such that individual cellular events can be controlled appropriately to meet the cell’s need. It is widely believed that this precise control is the result of intricate control over the spatial and temporal characteristics of the Ca2+ signal. This, in turn, occurs because of the localization, abundance and regulation of the Ca2+ handling machinery. These molecules, responsible for both the increase in Ca2+ (release and influx mechanisms) and terminating the signal (pumps and transporters and buffers) have been termed the “Ca2+ signaling toolkit” by Michael Berridge and colleagues [1]. A fundamental constituent of the “toolkit” responsible for shaping the temporal and spatial characteristics of Ca2+ release is the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R).

Architecture and function of IP3R

In non-excitable cells, stimulation with hormones, neurotransmitters and growth factors result in the production of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), activation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localized IP3R and the release of intracellular stored Ca2+ [1,6,7]. IP3Rs are encoded by 3 distinct genes (ITPR1, ITPR2, ITPR3) leading to the generation of ~300 kDa monomeric proteins (R1, R2, R3 and splice variants). The IP3R monomers oligomerize co-translationally to assemble into ~1100 kDa tetrameric channels [8-11]. The 3 isoforms share ~60-70% sequence homology and are conventionally divided into 3 key functional domains. The extreme amino terminus (NT) serves as the ligand binding domain (LBD) while the carboxyl terminal (CT) 6 transmembrane region contributes to the oligomerization and localization of the protein to the ER and to formation of the ion conducting pore between transmembrane helices 5 and 6. These two conserved regions are flanked by a large, but weakly conserved intermediary regulatory domain which, together with the poorly conserved extreme CT tail, contains numerous putative sites for regulation by different modulators, notably Ca2+, protein kinase A (PKA) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [9]. The variation in primary sequence homology between the 3 isoforms results in each subtype exhibiting distinct IP3R binding affinities and modulatory properties [12,13]. The differences in these properties and their contribution to the distinct Ca2+ release profiles of the 3 isoforms have been extensively investigated [9]. For instance, R2 has a ~ 3x and ~ 12x greater affinity for IP3 than R1 and R3, respectively [12]. Similarly, R2 is more sensitive to regulation by ATP than R1 or R3 [14,15]. Additionally, although PKA phosphorylation of R1 and R2 potentiates Ca2+ release and single channel activity, the phosphorylation occurs at very different residues [16-19]. Conversely, although a substrate for PKA, the activity of R3 does not appear to be regulated by PKA phosphorylation [20].

Evidence for heterotetramer formation

An additional layer of complexity that would be predicted to have a major influence over IP3R function, is the impact of heterotetrameric channel assembly. The initial studies identifying the IP3R subtypes reported that all 3 isoforms were commonly expressed at the message or protein level often in the same cells and tissues [21-25]. Subsequently, It was demonstrated that IP3R are probably ubiquitously expressed and all cells investigated expressed at least 2 isoforms [26]. Interestingly, it was noted that, while R1 is predominantly localized to neuronal cells and tissues, R2 and R3 are more frequently, though not exclusively, localized to peripheral tissues. These patterns of ubiquitous, yet differential expression have been confirmed in numerous subsequent studies [22,27-29]. Consistent with the existence of heterooligomer formation, co-localization and immunostaining studies also indicate that the different isoforms are often distributed similarly in subcellular compartments. For example, R1, R2 and R3 are all localized to the apical pole of pancreatic acinar cells on ER close to, or immediately below, the luminal membrane [30]. A similar localization of the three isoforms was reported in submandibular acinar cells [31]. In addition, a partial co-localization is evident in hepatocytes, as R2 specifically localizes to the pericanalicular regions at the apical portion of hepatocytes, while R1 is uniformly localized throughout the cytoplasmic ER [32,33].

The first strong evidence for hetero-oligomerization came from co-immunoprecipitation studies. For example, R1 and R2 were capable of associating with each other in rat liver lysate, and similar interactions between all 3 isoforms were documented in CHO-K1 cells [27]. In addition, heteromers of R1 and R2 were shown to assemble in AR42J cells, while similar associations between R1 and R3 were seen in RINm5F cells. Importantly, mixing lysates of different cell lines revealed that co-immunoprecipitation was not an artifact of post lysis dissociation and reassembly, but rather the consequence of isoform association in a heteromeric macromolecular complex [34]. Studies have also begun to address the biosynthetic “rules” governing heterotetramer formation. In COS-7 cells, heterologously expressed tagged IP3R were found not associate with native IP3R. Presumably, this lack of association occurs because the likelihood that endogenous IP3R is translated coincidently with ectopically expressed protein is low. Further, the degree of heterooligomer formation depended on the relative expression of the two recombinant isoforms and was shown to not follow a strict binomial distribution. Interestingly, these studies demonstrated that heterooligomers took longer to synthesize than homooligomers [35]. Lastly, cells co-transfected with cDNA encoding dominant negative mutations of the ligand binding domain of R3 and channel pore of R1 were able to produce functional channels, providing additional compelling evidence for heterotetramer formation [36].

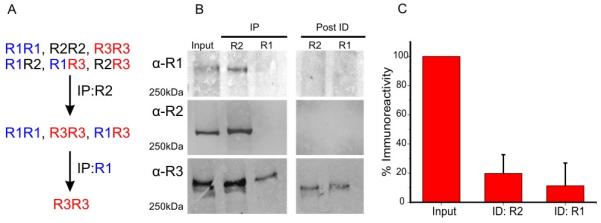

While these data provide strong evidence that heterotetramers are formed and further provide some biochemical “rules” for their generation, they do not provide any information regarding the relative abundance of homo vs. heterotetrameric assemblies. To investigate this important issue, our group has performed sequential immunodepletion of IP3R isoforms from mouse pancreatic lysates. R2 and R3 isoforms predominate in the exocrine pancreas, with R1 only accounting for ~3% of IP3Rs. To remove both homo and heterotetrameric assemblies containing R1, lysates were first incubated with α-IP3RR1 antisera (experimental strategy shown in Fig 1A). This indeed resulted in total depletion of R1 and a reduction in immunoreactivity associated with R2 and R3. These data are of course, entirely consistent with the presence of heterotetrameric IP3R in pancreatic acinar cells. Similarly, subsequent incubation of this lysate with α-IP3RR2, totally removed R2 expressing tetramers, leaving only R3 homomeric IP3R. Notably, these experiments revealed that only ~11% of R3 exists as a homotetramer in the pancreas (Fig 1B/C) [28]. While these data support the notion that heterotetrameric IP3R receptors are the predominant species in exocrine cells, further similar experiments are needed to establish that this is a common occurrence in cells expressing multiple IP3R subtypes.

FIG 1. Immunodepletion experiments supporting the existence of heteromeric IP3Rs in vivo.

(A) Schematic representation of strategy for immunodepletion experiment.

(B) Mouse pancreas lysates were subject to sequential immunoprecipitation, first with α-InsP3R2 (left blot, middle lane) followed by α-InsP3R1 (left blot, right lane) to maximally deplete R2 and R1, respectively (right blot). Equivalent supernatants, before (Input) and after immunodepletion (Post-ID), were separated using SDS-PAGE and probed with the indicated antibodies.

(C) A histogram comparing R3 immunoreactivity post R2 and post R2 + R1 immunodepletion. Quantitative densitometry revealed ~11% of R3 exists as homotetramers. Adapted from [28] with permission.

Functional implications of heterotetrameric IP3R

These studies clearly suggest that most cells and tissues express multiple IP3R isoforms that likely oligomerize into heterotetrameric complexes. Nevertheless, the functional consequences of heterotetramer formation have largely been overlooked. This is especially important given that each isoform exhibits markedly different regulatory and functional properties [9]. For example, it is not clear if the activity of heterotetramers simply reflects the integrated “blended” activity of the constituent monomers or alternatively if a particular monomer dominates the overall IP3R properties. Indeed, several studies exploring the regulatory properties of IP3Rs in native tissues have suggested that the overall characteristics of regulation of IP3R activity are not consistent with distinct populations of homotetrameric channels and may reflect unique properties of heterotetramers. For example, the IP3 binding affinity of R2 is ~3 fold greater than R1 and ~11 fold greater for R3 (14 nM vs. 50 nM vs. 163 nM; R2 vs R1 vs R3, respectively) [12]. Nevertheless, it has been reported that membrane fractions isolated from rat liver exhibited a Kd of 1.7 nM, obviously significantly different from that of R1 or R2 in isolation [37]. Additionally, experiments from our group have shown that the IP3 binding affinity to parotid acinar and pancreatic acinar cell membranes revealed Kds of 6.3 nM and 6.1 nM, respectively [38]. These Kd values are again significantly different from those reported for R2 and R3, in isolation, possibly pointing towards a degree of functional interaction between the isoforms.

Notably, studies investigating IP3R regulation by ATP have shown that the regulatory properties appear to be “dominated” by a specific isoform. Studies in DT40 3KO cells (an IP3R null background) stably expressing individual mammalian isoforms, reported R2 to have a ~3 fold higher affinity for ATP than R1 and ~10 fold higher than R3, respectively (40 μM vs. 150 μM vs. 400 μM) [14,15]. In addition, while R1 and R3 appear to require ATP at all [IP3] to achieve maximal release rates, the activity of R2 is only modulated by ATP at sub-maximal [IP3]. Given this information, it is interesting to note that despite approximately equal expression of R2 and R3, Ca2+ release assays performed on mouse pancreatic acini revealed an EC50 of 38 μM and activity was not modulated at saturating [IP3]; properties essentially identical to R2 in isolation. In contrast, pancreatic acini isolated from R2 KO mice revealed an EC50 of 450 μM, indistinguishable from R3 in isolation [39]. Similar EC50 values were seen in AR42J (10 μM) and RinM5F cells (430 μM), which predominantly express R2 and R3, respectively [26]. Moreover, transient transfection of RinM5F cells with cDNA encoding murine R2 resulted in a ~10 fold increase in sensitivity to ATP. Together, these data point towards R2 dictating the ATP sensitivity of IP3Rs [39]. In hindsight, these findings are entirely consistent with studies using DT40 cells expressing native chicken IP3Rs and engineered cells expressing a defined complement of IP3R by targeted knockdown of either one, two or three genes. [13]. Ca2+ release assays revealed that R2 dominated the ATP sensitivity, followed by R1 and subsequently R3 (R2>R3>R1). In stark contrast, [IP3] concentration vs response relationships revealed a ‘blended’ sensitivity, further contributing to the notion that the different modes of IP3R regulation are differentially influenced by the various isoforms.

Generating heterotetrameric IP3R with defined composition

The major limitation to these studies conducted in cultured cells and isolated tissues is the inability to predict the exact proportion of each isoform in a heterotetramer, or indeed the percentage of homotetramers in the IP3R population. Similar issues arise using any approach utilizing ectopic co-expression of cDNA constructs encoding multiple IP3R subtypes. To circumvent this, our group recently described a strategy whereby the functional characteristics of heterotetramers with unequivocally defined composition can be explored [28]. This approach is based on engineering concatenated IP3R whereby the C-terminus of the initial monomer is connected to the N-terminus of a subsequent monomer by a short flexible glutamine rich linker. In theory, this approach can be extended to construct cDNA encoding the tetrameric protein. This paradigm has been successfully utilized in the past to study the functional characteristics of a variety of multi-subunit channels including Orai and various K+ channel family members [40-44]. The extremely large size of the cDNA encoding IP3R, however, made constructing tetrameric IP3R concatamers initially a rather daunting undertaking. We therefore decided to construct cDNA encoding dimeric InP3R in a novel vector designed to manipulate large DNA strands (see cartoon of pJAZZmamm in Fig 2A). The guiding rationale for this approach being that, upon expression, the biosynthetic machinery of the cell might dimerize the concatenated proteins to form tetrameric channels of defined subunit composition. Briefly, linear cDNA constructs encoding mammalian IP3R encoding all possible combinations of concatenated homodimeric and heterodimeric IP3Rs were successfully generated and stably expressed in DT40 3KO cells (Fig 2B and [28]). Remarkably, these proteins were localized to ER membranes and exclusively assembled into tetrameric receptors in an identical fashion to channels assembled from monomeric constructs (Fig 2C). Functionally, competitive IP3R binding assays demonstrated that the dimeric proteins bound IP3R comparably to the monomers [28]. Importantly, cell surface receptor stimulation and Ca2+ release assays revealed that all channels assembled from concatenated receptors formed fully functional IP3R. A closer investigation into the single channel properties using ‘on-nuclear’ patch clamp revealed that the homodimeric R1R1 and R2R2 exhibited open probabilities and gating characteristics similar to the R1 and R2 monomeric proteins, thereby indicating that they are functionally indistinguishable [28].

Fig 2. Generation of concatenated IP3R constructs and their stable expression DT40-3KO IP3R null cells.

(A) InsP3R ‘head’ and ‘tail’ subunits were subcloned into pJAZZmamm, a linear vector plasmid developed from N15 coliphage (Lucigen).

(B) Representative western blots showing that concatenated dimer constructs were stably transfected and expressed into DT40-3KO cells.

(C) Representative blue native gels demonstrating that DT40-3KO cells express monomeric or dimeric constructs are assembled to form tetramers. Adapted from [28] with permission.

The generation of tetrameric IP3R from defined heterodimers now allows us to begin to address a longstanding question as to how the distinct subunit composition of a heterotetramer contributes to the functionality and regulation of the receptor. In DT40 cells expressing a single isoform, B cell receptor stimulation with sub maximal α-IgM resulted in each IP3R subtype exhibiting Ca2+ signals with distinct temporal “signatures” [13]. The characteristics of these Ca2+ signals are believed to depend on the characteristic IP3R binding and integration of the distinct regulatory properties of each isoform. For example, while R1 was shown to generate monophasic Ca2+ transients, R2 was shown to produce long lasting oscillatory Ca2+ signals. Similar “signatures” were observed by our group in DT40 3KO cells stably expressing mammalian R1 and R2 monomer and importantly, concatenated dimer constructs [28]. Interestingly, cells expressing R1R2 heterodimers, unequivocally forming a tetramer with equal numbers of R1 and R2 monomers, generated robust oscillatory Ca2+ signals, qualitatively and quantitatively similar to those generated by R2 alone [28] (Fig 3A-F). R2 dominance was also observed in cells expressing R2R3 heterodimers (data not shown). Further investigation into IP3R regulation revealed similar dominant characteristics of R2. As noted, regulation of R1 and R2 by ATP has distinct defining characteristics, which include specific gating kinetics observed at the single-channel level. Increasing [ATP] prolongs the duration of R1 bursts, while ATP increased the number of bursts without affecting duration for R2. As shown in Fig 3 G-I), ATP does not regulate the activity of R1R2 heterodimers at saturating [IP3] and mimics the gating characteristics formed by R2 monomers and concatenated dimers [28], clearly demonstrating that two R2 subunits within the heterotetramer leads to R2 dominant properties.

Fig 3. Activity of concatenated heterodimers is dominated by R2.

(A-F) Activation of B cell Receptor in DT40-3KO cells stably expressing R1 and R2 containing monomeric and dimeric InsP3Rs results in characteristic Ca2+ signals. R2 properties appear to dominate.

(G-I) Representative single channel K+ current recordings of R1R1, R2R2 and R1R2 dimers, measured using on-nucleus patch clamp, at 1 or 10 μM InsP3 in the presence of 200 nM free Ca2+ and either 100 μM or 5 mM ATP. R2 properties appear to dominate. Adapted from [28] with permission.

Clearly, the use of concatenated IP3R constructs is a powerful tool to study the function and regulation of IP3R of defined composition. In fact, our group has successfully generated a membrane localized, functional homotetrameric R1R1R1R1 concatamer [28]. The generation of this tetramer provides proof of principle that any possible combination of heterotetrameric IP3R can potentially be generated and studied. This may be especially important in studying the impact of incorporation of defined numbers of disease associated IP3R mutations to mimic heterozygous expression. Furthermore, given that all known modulatory motifs are present in each monomer and it is not known how many monomers need to be “engaged” to influence activity, the ability to mutate residues in defined numbers of monomers should allow us to establish the stoichiometry required for channel regulation. A priority is to definitely answer fundamental questions such as the number of IP3 molecules required to bind to gate the IP3R.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank members of the Yule lab for there helpful comments during the course of this work. The work was supported by grants from The NIH (NIDCR) R01-DE14756 and R01-DE19245.

References

- 1.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:552–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambudkar IS. Ca(2)(+) signaling and regulation of fluid secretion in salivary gland acinar cells. Cell Calcium. 2014;55:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–2232. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goonasekera SA, Molkentin JD. Unraveling the secrets of a double life: contractile versus signaling Ca2+ in a cardiac myocyte. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Streb H, Bayerdorffer E, Haase W, Irvine RF, Schulz I. Effect of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate on isolated subcellular fractions of rat pancreas. J Membr Biol. 1984;81:241–253. doi: 10.1007/BF01868717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streb H, Irvine RF, Berridge MJ, Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983;306:67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foskett JK, White C, Cheung KH, Mak DO. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:593–658. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel S, Joseph SK, Thomas AP. Molecular properties of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium. 1999;25:247–264. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph SK, Boehning D, Pierson S, Nicchitta CV. Membrane insertion, glycosylation, and oligomerization of inositol trisphosphate receptors in a cell-free translation system. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1579–1588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwai M, Michikawa T, Bosanac I, Ikura M, Mikoshiba K. Molecular basis of the isoform-specific ligand-binding affinity of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12755–12764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyakawa T, Maeda A, Yamazawa T, Hirose K, Kurosaki T, Iino M. Encoding of Ca2+ signals by differential expression of IP3 receptor subtypes. EMBO J. 1999;18:1303–1308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betzenhauser MJ, Wagner LE, 2nd, Park HS, Yule DI. ATP regulation of type-1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor activity does not require walker A-type ATP-binding motifs. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16156–16163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betzenhauser MJ, Wagner LE, 2nd, Iwai M, Michikawa T, Mikoshiba K, Yule DI. ATP modulation of Ca2+ release by type-2 and type-3 inositol (1, 4, 5)-triphosphate receptors. Differing ATP sensitivities and molecular determinants of action. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21579–21587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801680200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betzenhauser MJ, Fike JL, Wagner LE, 2nd, Yule DI. Protein kinase A increases type-2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor activity by phosphorylation of serine 937. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25116–25125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang TS, Tu H, Wang Z, Bezprozvanny I. Modulation of type 1 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor function by protein kinase a and protein phosphatase 1alpha. J Neurosci. 2003;23:403–415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00403.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner LE, 2nd, Li WH, Yule DI. Phosphorylation of type-1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors by cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases: a mutational analysis of the functionally important sites in the S2+ and S2− splice variants. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45811–45817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soulsby MD, Alzayady K, Xu Q, Wojcikiewicz RJ. The contribution of serine residues 1588 and 1755 to phosphorylation of the type I inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by PKA and PKG. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soulsby MD, Wojcikiewicz RJ. Calcium mobilization via type III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors is not altered by PKA-mediated phosphorylation of serines 916, 934, and 1832. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maranto AR. Primary structure, ligand binding, and localization of the human type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor expressed in intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1222–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newton CL, Mignery GA, Sudhof TC. Co-expression in vertebrate tissues and cell lines of multiple inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptors with distinct affinities for InsP3. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28613–28619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blondel O, Takeda J, Janssen H, Seino S, Bell GI. Sequence and functional characterization of a third inositol trisphosphate receptor subtype, IP3R-3, expressed in pancreatic islets, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and other tissues. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11356–11363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mignery GA, Newton CL, Archer BT, 3rd, Sudhof TC. Structure and expression of the rat inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12679–12685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudhof TC, Newton CL, Archer BT, 3rd, Ushkaryov YA, Mignery GA. Structure of a novel InsP3 receptor. EMBO J. 1991;10:3199–3206. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wojcikiewicz RJ. Type I, II, and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are unequally susceptible to down-regulation and are expressed in markedly different proportions in different cell types. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11678–11683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monkawa T, Miyawaki A, Sugiyama T, Yoneshima H, Yamamoto-Hino M, Furuichi T, Saruta T, Hasegawa M, Mikoshiba K. Heterotetrameric complex formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor subunits. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14700–14704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alzayady KJ, Wagner LE, 2nd, Chandrasekhar R, Monteagudo A, Godiska R, Tall GG, Joseph SK, Yule DI. Functional inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors assembled from concatenated homo- and heteromeric subunits. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29772–29784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.502203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Smedt H, Missiaen L, Parys JB, Henning RH, Sienaert I, Vanlingen S, Gijsens A, Himpens B, Casteels R. Isoform diversity of the inositol trisphosphate receptor in cell types of mouse origin. Biochem J. 1997;322(Pt 2):575–583. doi: 10.1042/bj3220575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yule DI, Ernst SA, Ohnishi H, Wojcikiewicz RJH. Evidence that zymogen granules are not a physiologically relevant calcium pool - Defining the distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in pancreatic acinar cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:9093–9098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee MG, Xu X, Zeng W, Diaz J, Kuo TH, Wuytack F, Racymaekers L, Muallem S. Polarized expression of Ca2+ pumps in pancreatic and salivary gland cells. Role in initiation and propagation of [Ca2+]i waves. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15771–15776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirata K, Pusl T, O'Neill AF, Dranoff JA, Nathanson MH. The type II inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor can trigger Ca2+ waves in rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1088–1100. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruglov EA, Gautam S, Guerra MT, Nathanson MH. Type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor modulates bile salt export pump activity in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2011;54:1790–1799. doi: 10.1002/hep.24548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wojcikiewicz RJ, He Y. Type I, II and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor co-immunoprecipitation as evidence for the existence of heterotetrameric receptor complexes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:334–341. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph SK, Bokkala S, Boehning D, Zeigler S. Factors determining the composition of inositol trisphosphate receptor hetero-oligomers expressed in COS cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16084–16090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boehning D, Joseph SK. Direct association of ligand-binding and pore domains in homo- and heterotetrameric inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. EMBO J. 2000;19:5450–5459. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guillemette G, Balla T, Baukal AJ, Catt KJ. Characterization of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and calcium mobilization in a hepatic plasma membrane fraction. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4541–4548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giovannucci DR, Bruce JI, Straub SV, Arreola J, Sneyd J, Shuttleworth TJ, Yule DI. Cytosolic Ca(2+) and Ca(2+)-activated Cl(−) current dynamics: insights from two functionally distinct mouse exocrine cells. J Physiol. 2002;540:469–484. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park HS, Betzenhauser MJ, Won JH, Chen J, Yule DI. The type 2 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptor determines the sensitivity of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release to ATP in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26081–26088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804184200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groot-Kormelink PJ, Broadbent S, Beato M, Sivilotti LG. Constraining the expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by using pentameric constructs. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:558–563. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liman ER, Tytgat J, Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicke A, Rettinger J, Schmalzing G. Monomeric and dimeric byproducts are the principal functional elements of higher order P2X1 concatamers. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:243–252. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Both Orai1 and Orai3 are essential components of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels. J Physiol. 2008;586:185–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Orai1 subunit stoichiometry of the mammalian CRAC channel pore. J Physiol. 2008;586:419–425. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]