Abstract

Background

Through delayed HIV disease progression, Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) may reduce direct medical costs, thus at least partially offsetting therapy costs. Recent findings regarding the secondary preventive benefits of HAART necessitate careful consideration of funding allocations for HIV/AIDS care. Our objective is to estimate non-HAART direct medical costs at different levels of disease progression and over time in British Columbia, Canada.

Methods

We considered the population of individuals with HIV/AIDS within a set of linked disease registries and health administrative databases (N=11,836) from 1996–2010. Costs of hospitalization, physician billing, diagnostic testing and non-HAART medications were calculated in 2010$CDN. Effects of covariates on quarterly costs were assessed with a two-part model with logit for probability of nonzero costs and a generalized linear model (GLM). Net effects of CD4 strata on direct non-HAART medical costs were evaluated over time during the study period.

Results

Compared to person-quarters in which CD4>500mm3, costs were $185(95% confidence interval:132,239) greater for CD4:350–500mm3, $441(366,516) greater for CD4 200–350mm3 and $1173(1051,1294) greater when CD4<200mm3. Prior to HIV care initiation, individuals incurred costs $385(283,487) greater than in periods with CD4>500mm3. Hospitalization comprised the majority of the increment in costs amongst those with no measured CD4. Evaluated at CD4 state conditional means, those with CD4<200mm3 incurred quarterly costs of $5781(4716,6846), versus $1307(1154,1460) (p<0.001) for CD4≥500mm3 in 2010.

Conclusion

Non-HAART direct medical costs were substantially lower for individuals during periods of sustained virologic suppression and high CD4 count. HIV treatment and prevention evaluations require detailed health resource use data to inform funding allocation decisions.

Introduction

Sustained adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) stops viral replication, promotes immune reconstitution, prevents disease progression and prolongs survival[1,2]. As a result, HAART has been documented to decrease the incidence of episodes of acute care, thus reducing health resource utilization and offsetting the costs of antiretroviral medications[3–5].

Evidence for the secondary preventive effect of HAART on HIV transmission[6] has spawned efforts to scale-up HIV treatment programs globally[7]. In turn, this has spurred further epidemiological and economic modeling efforts to project outcomes of various HIV treatment and prevention strategies,[5, 8–11] to inform optimal use of scarce healthcare resources. In British Columbia (BC) Canada, under the auspices of the Ministry of Health, the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BC-CfE) partnered with a consortium of provincial Health Care partners to implement the “Seek and Treat for Optimal Prevention of HIV and AIDS” (STOP HIV & AIDS) pilot project[12].

The majority of HIV transmission models employed in cost-effectiveness analyses model disease progression via transitions between health states defined by CD4 strata[11,13–15]. Recent systematic reviews of published HIV costing studies revealed only nine studies that provided adequate cost data, and valid comparisons of total direct medical costs between studies were not possible because of differences in the specific components included, the heterogeneous nature of study populations in terms of disease stage, the sources and methods used to estimate unit costs, and the level of aggregation at which results were reported[16,17]. Further, many of these studies were based on pre- and early-HAART era patient populations. Given the substantial innovations in antiretroviral treatment and subsequent changes in therapeutic guidelines, it is likely that individuals more recently diagnosed and initiating treatment using modern regimens follow substantially different trajectories of health resource use, with potentially important implications in health resource allocation decisions.

Perhaps most importantly however, none of the reviewed studies captured direct medical costs for individuals before initiating HAART. Given the transmissibility of HIV/AIDS, adequately capturing health and economic benefits to interventions require mathematical models that capture HIV transmission explicitly; inclusion of those not yet accessing HIV treatment is necessary as these individuals disproportionately drive HIV transmission. We take advantage of a unique linked population-level dataset that captures health resource utilization for individuals linked to HIV care (ie. receiving HIV diagnostic testing or antiretroviral treatment), as well as periods prior to linkage for those entering HIV care to characterize and quantify health resource use for this under-researched population[18].

From a methodological standpoint, there has been substantial debate regarding appropriate practices for modeling healthcare costs [19–23]. This revolves around the non-normal distribution of individual-level healthcare costs, which are typically characterized by a nontrivial fraction of zero outcomes among repeated measurements, non-negative measurements of the outcomes, and a positively skewed empirical distribution of the non-zero realizations. Each of these problems precludes the use of standard linear models and demand careful consideration of the modeling strategy. Therefore, our objective is to longitudinally characterize direct non-HAART medical costs through stages of linkage to care and disease progression for HIV-infected individuals in BC, Canada throughout the HAART era.

Methods

Subjects

This study was based on a provincial-level linkage of a set of seven health administrative databases and disease registries, including the BC-CfE drug treatment program and virology registries (antiretroviral dispensations, plasma viral load (pVL) and CD4 tests), the BC Centre for Disease Control HIV testing database (HIV diagnosis), the Medical Services Plan database (physician billing records), the discharge abstract database (hospitalizations), the BC PharmaNet database (non-antiretroviral drug dispensations) and the BC Vital statistics database (deaths). We considered all individuals identified as HIV-positive within this set of databases from January 1st,1996 to March 31st, 2010. Further details regarding the construction of the cohort and available databases have previously been described[18]. For each individual, quarterly data was available from the point of HIV diagnosis to death, administrative loss to follow-up or censorship (ongoing care as of March 30th, 2010). We chose a quarterly timeframe to mirror evidence-based CD4 and pVL monitoring guidelines, as per the IAS-USA guidelines [24]. Administrative loss was defined as no records in any of the linked databases for a period of at least 18 months.

The study cohort was followed in a unique environment characterized by universal free medical care, including free in- and out-patient care, laboratory monitoring, and antiretroviral drugs. pVL data capture in the BC-CfE registries are complete for the population of individuals with HIV/AIDS in the province, and CD4 cell count data capture has previously been estimated at 80%[25].

Dependent Variables

The primary dependent variables considered in these analyses were direct non-HAART medical costs, and its components: costs of hospitalization, physician billing, and non-HAART drug dispensations. Costs of HAART were excluded from this analysis as these patient-level costs follow a different process, influenced more by technological development of antiretroviral medications and changes in clinical practice guidelines and less by disease progression[5,26].

Costs of physician billings as well as medication dispensations, including pharmacy dispensation costs, were derived directly from the BC MSP and BC PharmaNet datasets, respectively. The BC MSP is an itemized schedule of reimbursement fees for the full range of medical services, therefore they represent average costs of producing care from a third party payer perspective. The costs of inpatient care were estimated by multiplying hospital resource intensity weights, collected throughout the province and study period, by an estimated cost per weighted case (CWC) for the province of British Columbia in 2010[27]. CWC is based on standard methodologies developed by the Canadian Institution of Health Information (CIHI), and is used across Canada in the analysis of hospital services[28]. Case-mix group costing, similar to diagnostic-related group costing in the US, are used by healthcare funding organizations to judge intensity of service utilization and make subsequent funding decisions[28]. Finally, non-HAART costs of medical care were calculated as the sum of the costs of hospitalizations, physician claims, non-HAART medication dispensations and diagnostic testing, including CD4, pVL and resistance testing. For the latter, counts of CD4, pVL and resistance tests were multiplied by unit costs derived from the BCCDC and BC-CfE. All costs were adjusted for inflation using the Canadian Consumer Price Index [29] and presented in 2010$CDN.

Independent variables

As determinants of the set of defined study outcomes, we considered both fixed and time-varying effects of demographic indicators, clinical stage and access to treatment. Patient demographics included age, gender and temporal period of HIV diagnosis (pre-1996; 1996–1999; 2000–2003; post-2003). Medical comorbidity was captured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, indicating the level of medical comorbidity from ICD-9/10 codes in hospitalizations in the prior year. The CCI is a weighted comorbidity score ranking 22 conditions by disease severity (individual conditions are given a weight of 1–6 points according to the risk of mortality) on a negative, continuous scale[30]. Illicit drug use status was defined as ever having any illicit drug-related service delivered (including drug-related inpatient and outpatient care, as indicated by a previously-defined set ICD-9/10 codes[31], opioid substitution treatment dispensations in the BC PharmaNet database, or other addiction services, captured in the BC Addiction Information Management Systems database. We also included linear and quadratic time trend variables.

Indicators of clinical stage included CD4 cell count at initial measurement, current CD4 cell count (including CD4 measurements within 6 months of the earliest date in strata (≥500mm3; 350–499mm3; 200–349mm3; <200mm3; CD4 unmeasured), and the area under the log10(pVL) curve (AUC pVL) in the year of the quarterly observation, stratified into five categories: (≥3.5; 3–3.49; 2.7–2.99; <2.7; AUC pVL unmeasured). As pVL and CD4 measures are known to have independent effects on AIDS-related illness and mortality[32,33], time-varying effects for each measure were included. AUC values were used only for pVL measurements due primarily to their volatility; this measure was found to be a more sensitive indicator of disease severity than the most recent pVL measurement[34]. AUC pVL strata corresponded to sustained log10pVL<2.7 (pVL<500 copies per mL); 3.0 (pVL<1000 copies per mL) and 3.5 (pVL<3500 copies per mL) over a 12-month period and were chosen based on the empirical distribution in the data. CD4 strata were chosen for clinical significance and their historic use as treatment initiation thresholds in IAS-USA guidelines[24]. Following linkage to HIV care (with linkage to care defined as the first receipt of HIV diagnostic test (CD4 or pVL) following diagnosis), we executed a multiple imputation procedure to impute values in quarters with missing AUC pVL or CD4 measures. A time-varying indicator of HAART receipt captured whether antiretroviral medication was received during the person-quarter. While CD4 and pVL may be considered intermediates in the causal pathway between HAART and non-HAART medical costs, we included this covariate to capture additional variation attributable to HAART receipt, which could be considered an indicator of engagement with the health care system.

The study population included individuals unlinked to HIV care for some period of follow-up or throughout follow-up. We included the ‘unmeasured’ CD4 and AUC pVL categories to allow for direct comparison of health resource use to the various stages of disease progression following linkage to care. In a supplemental analysis focusing on observations prior to linkage to HIV care, we compare those unlinked to HIV care throughout follow-up to those eventually linking to HIV care.

Statistical Analysis

Two-part, or hurdle models were estimated to account for excess zeroes in each of the selected dependent variables. In the first stage, generalized linear models were specified with binomial distributions and logit link functions[22]. In the second stage, modified Park tests were executed to determine the appropriate distributional family[35]. Models were initially estimated with gamma distribution and log link function. Huber-White standard errors were calculated to control for intra-individual correlation in repeated measurements in the generalized linear models[36,37].

Finally, following a previous application[38], we used the product rule to determine the total marginal effects of CD4 strata on the set of defined dependent variables. Specifically, total costs (TC) were modeled as the product of 2 factors (TC = P × L), where P is the probability of having nonzero costs and L is the level of the nonzero costs that occur. The 2-step procedure generates separate estimates of the marginal effects of CD4 strata on each factor, which we call P′(CD4) and L′ (CD4), respectively. To generate an estimate of the overall effect on costs of a change in CD4, we apply the product rule of calculus to derive TC′ (CD4) = [P′ (CD4) × L] + [P × L′ (CD4)].. We interpret TC′ (CD4) as the marginal effect on total costs of a change in CD4 stratum. Marginal effects for L and P were evaluated at the mean value of all covariates. We subsequently estimate mean quarterly stratum-specific non-HAART medical costs by calendar year throughout the study period, evaluated both at unconditional population-level mean-valued covariates, and CD4 stratum and calendar year-specific mean-valued covariates. The model was estimated using the tpm procedure and margins post-estimation command in STATA. Robust standard errors for the combined marginal effects of covariates on total costs were estimated using the delta method [39].

Results

Our study population was comprised of 11,836 individuals identified as HIV-positive with at least two quarters of observation, 2,785 (23.5%) of which never accessed HAART during study follow-up. The mean duration of follow-up was 7.3 person-years overall (4.6 for those never accessing HAART, and 8.1 for those ever accessing HAART). A total of 2,883 individuals died during study follow-up, while another 448 were administratively lost to follow-up. As a result, 8,505 (71.9%) remained in the study at the end of study follow-up.

Summary statistics on the study population, direct non-HAART medical costs and their components are detailed in Table 1. The mean age of the population at HIV diagnosis was 38.8 (SD:11.0), 19.6% were female, and 45.6% had accessed health services for substance abuse at some point during follow-up. Nearly 53% of the sample were diagnosed before 1999, 25% had no baseline CD4 measurement, and 42.5% had no baseline pVL measurement. All cost outcomes were highly skewed, and mean estimates were heavily influenced by outlying observations. The hospitalization cost outcome was most frequently equal to zero (91.4%), while total costs were zero in 10.7% of all person-quarters of observation. Among non-zero observations, mean total costs were $2,159 (standard deviation (SD): $6,777), though median costs were $718 (Interquartile range (IQR): $340–1564); in comparison, quarterly costs at the 99th percentile were $30,080 (All costs in 2010$CDN). Costs of hospitalizations among non-zero responses were highest across non-HAART cost categories, at a mean of $10,957 (SD: $16,895) per person-quarter. The distribution of healthcare cost data features a high frequency of zero responses, right-skew and thick tails, indicating a large range of outlying high-cost observations.

Table 1.

Summary statistics on study subjects and quarterly cost and health resource use data (N=11,836; 344,328 observations)

| Full sample [N=11,836] | |

|---|---|

| Age [Mean (SD)] | 38.8 (11.0) |

| Female gender | 2315 (19.6) |

| Substance Abuse* | 5368 (45.4) |

| Diagnosed: <1996 | 2493 (21.1) |

| 1996–1999 | 3775 (31.9) |

| 2000–2003 | 2438 (20.6) |

| 2004–2007 | 2119 (17.9) |

| 2008–2011 | 1006 (8.5) |

| Baseline CD4: missing | 2961 (25.0) |

| CD4<200 | 1056 (8.9) |

| 200—350 | 1678 (14.2) |

| 350–500 | 2730 (23.1) |

| >500 | 3411 (28.8) |

| Baseline log10 pVL: missing (%) | 5034 (42.5) |

| non-missing | 6802 (57.5) |

| Time-varying covariates [% of all observations (N=344,328)] | |

| On HAART | 54.1 |

| CD4: not measured | 33.7 |

| CD4: >500 | 22.7 |

| CD4: 350–500 | 15.3 |

| CD4: 200–350 | 15.7 |

| CD4: <200 | 12.5 |

| AUC pVL: not measured | 18.5 |

| AUC pVL: ≥3.5 | 33.0 |

| AUC pVL: 3.0–3.5 | 9.0 |

| AUC pVL: 2.7–3.0 | 21.4 |

| AUC pVL: <2.7 | 18.1 |

| Hospitalization costs | Physician billing costs | Drug dispensation costs | Total non-HAART medical costs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % zero | 91.43 | 16.94 | 25.23 | 10.74 |

| Mean | 10,957.24 | 493.85 | 533.16 | 2,159.35 |

| SD | 16,895.21 | 703.66 | 1,191.82 | 6,776.95 |

| Skewness | 4.85 | 6.25 | 33.49 | 12.11 |

| Kurtosis | 43.14 | 83.88 | 2,932.44 | 266.12 |

| 1st percentile | 538.70 | 22.73 | 4.43 | 20.00 |

| 25th percentile | 2,379.98 | 131.95 | 69.32 | 339.73 |

| 50th percentile | 5,465.50 | 295.37 | 225.43 | 718.17 |

| 75th percentile | 12,121.29 | 583.63 | 643.13 | 1,563.54 |

| 99th percentile | 77,769.01 | 3,370.65 | 3,929.58 | 30,080.24 |

SD: standard deviation; HAART: highly active antiretroviral therapy; AUC: area under the curve; pVL: plasma viral load;

ever accessed health services for substance abuse. All costs in 2010$CDN.

Results of the two-stage analysis on direct non-HAART medical costs are presented in Table 2. Marginal effects on the probability of non-zero cost in a given observation period and costs in non-zero observations are presented. Female gender, older age, high levels of medical comorbidity (CCI scores) and ever having accessed health services for substance abuse were all statistically significantly associated with higher direct non-HAART medical costs. Costs were substantially higher in observations within 3 months of mortality, and quarters in which individuals were receiving HAART. Those with extended durations of unsuppressed pVL (indicated by AUC pVL) also incurred higher quarterly costs. Finally, lower current CD4 cell counts were statistically significantly associated with progressively higher direct non-HAART medical costs, while observations prior to linkage to HIV care (CD4 unmeasured)were also associated with higher costs compared to periods of CD4>500mm3.

Table 2.

Marginal effect estimates from two-stage analysis on direct non-HAART medical costs

| Combined effects from Two-Part Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dy/dx | 95% CI | p | ||

| Calendar year | 8.07 | −0.40 | 16.53 | 0.062 |

| Female | 500.38 | 398.36 | 602.41 | < 0.001 |

| Age (in deciles) | 349.29 | 312.17 | 386.40 | < 0.001 |

| CCI | 355.35 | 338.58 | 372.13 | < 0.001 |

| Substance Abuse | 1369.60 | 1294.37 | 1444.83 | < 0.001 |

| Mortality within 3 months | 9281.24 | 8365.16 | 10197.32 | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosed: <1996 | −74.86 | −207.69 | 57.97 | 0.269 |

| Diagnosed: 1996–1999 | −360.33 | −483.11 | −237.55 | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosed: 2000–2003 | −145.34 | −276.81 | −13.87 | 0.030 |

| Diagnosed: ≥2004 | Ref. | |||

| On HAARTt | 779.05 | 678.66 | 879.44 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline CD4: unmeasured | 357.46 | 123.85 | 591.08 | 0.003 |

| Baseline CD4: ≥500 | Ref. | |||

| Baseline CD4: 350–500 | −136.39 | −268.91 | −3.88 | 0.044 |

| Baseline CD4: 200–350 | −252.49 | −371.70 | −133.28 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline CD4: <200 | −85.00 | −210.56 | 40.55 | 0.185 |

| AUC PVLt: unmeasured | 119.39 | −105.58 | 344.37 | 0.298 |

| AUC PVLt: >=3.5 | 847.89 | 742.88 | 952.89 | < 0.001 |

| AUC PVLt: 3–3.5 | 649.50 | 534.05 | 764.94 | < 0.001 |

| AUC PVLt: 2.7–3 | 115.47 | 47.76 | 183.18 | 0.001 |

| AUC PVLt: <2.7 | Ref. | |||

| CD4t: unmeasured | 385.34 | 283.27 | 487.41 | < 0.001 |

| CD4t: ≥500 | Ref. | |||

| CD4t: 350–500 | 185.15 | 131.68 | 238.62 | < 0.001 |

| CD4t: 200–350 | 441.01 | 366.27 | 515.76 | < 0.001 |

| CD4t: <200 | 1172.73 | 1050.98 | 1294.48 | < 0.001 |

HAART: highly active antiretroviral therapy; AUC: area under the curve; pVL: plasma viral load; CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; dy/dx: marginal effect of covariate on study outcome in natural units (stage 1 and 2 combined, 2010$CDN); 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p: p-value.

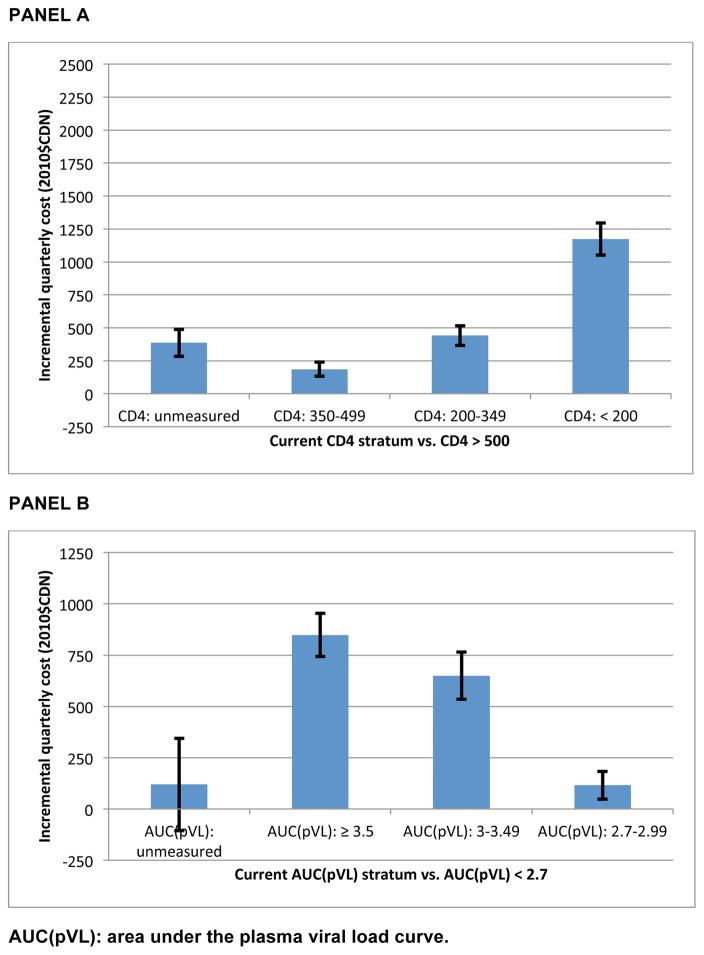

The net effects of current CD4 and AUC pVL stratum on direct non-HAART medical costs (based on mean-valued covariates over the complete follow-up period), estimated using the product rule as detailed in the methods section above, are presented in Figure 1. Compared to person-quarters in which CD4>500mm3, costs were $185(95% confidence interval:132,239) greater for CD4:350–500mm3, $441(366,516) greater for CD4 200–350mm3 and $1173(1051,1294) greater when CD4<200mm3. Prior to HIV care initiation, individuals incurred costs $385(283,487) greater than in periods with CD4>500mm3. A subsequent analysis focusing on durations of follow-up prior to linkage to HIV care found that those unlinked throughout follow-up incurred quarterly costs that were not statistically significantly different from those linking to care during follow-up (pre-linked vs. unlinked: −$54.07; p=0.429; results available in supplementary appendix).

Figure 1.

Net effect of current CD4 count strata and AUC(pVL) on direct non-HAART medical costs, evaluated at unconditional population-level means

AUC(pVL): area under the plasma viral load curve.

The net effects of current CD4 stratum on direct non-HAART medical costs are decomposed in Table 3 (complete sets of marginal effects from which these estimates were drawn were presented in the supplementary appendix). Compared to person-quarters with CD4≥500mm3, those with no available CD4 data (ie. prior to linkage to HIV care) incurred similar non-HAART drug dispensation costs (-$22 (-$52, $8), but substantially higher costs of hospitalization ($341 (267, 416)) and higher physician billing costs as well ($47 ($32, $62)); the increment in hospitalization and physician billing costs among those with no available CD4 data were lower than the CD4<200mm3 stratum, but higher than the CD4: 200–349mm3 stratum.

Table 3.

Net effect of current CD4 count strata on direct non-HAART medical costs by component, evaluated at unconditional population-level means

| Incremental Cost (2010$CDN) | SE | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hospitalizations

| ||||

| CD4t: unmeasured | 341.20 | 37.91 | 266.89 | 415.51 |

| CD4t: ≥500 | Ref. | |||

| CD4t: 350–500 | 163.02 | 26.68 | 110.73 | 215.30 |

| CD4t: 200–350 | 366.94 | 34.84 | 298.66 | 435.23 |

| CD4t: <200 | 846.96 | 54.64 | 739.85 | 954.06 |

|

| ||||

|

Physician billing

| ||||

| CD4t: unmeasured | 47.21 | 7.46 | 32.58 | 61.84 |

| CD4t: ≥500 | Ref. | |||

| CD4t: 350–500 | 24.09 | 3.96 | 16.33 | 31.85 |

| CD4t: 200–350 | 58.25 | 5.79 | 46.90 | 69.60 |

| CD4t: <200 | 127.21 | 8.41 | 110.72 | 143.69 |

|

| ||||

|

Non-HAART drug dispensation

| ||||

| CD4t: unmeasured | −22.05 | 15.25 | −51.94 | 7.84 |

| CD4t: ≥500 | Ref. | |||

| CD4t: 350–500 | 30.44 | 7.10 | 16.51 | 44.36 |

| CD4t: 200–350 | 83.77 | 10.80 | 62.59 | 104.94 |

| CD4t: <200 | 222.20 | 18.68 | 185.60 | 258.81 |

SE: standard error, as computed by the delta method; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. Complete results for each of the models is presented in the supplementary appendix, Table A1.

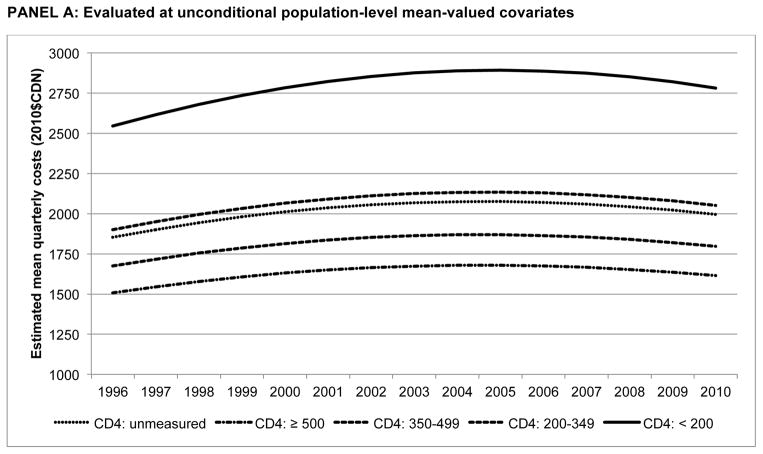

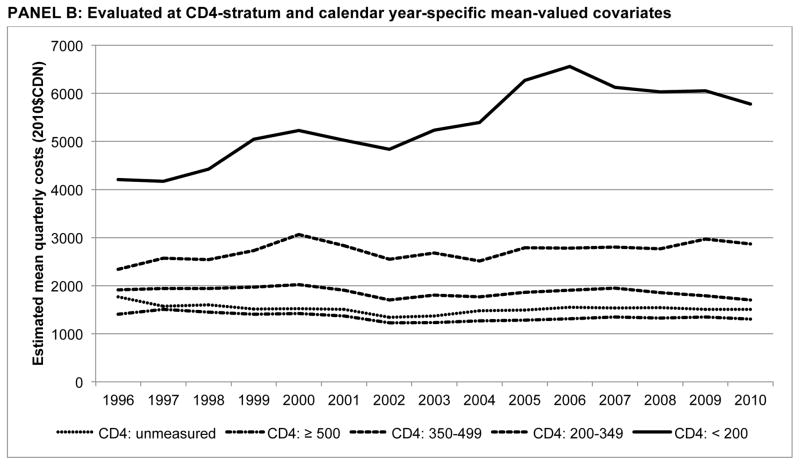

Finally, Figure 2 presents estimated mean quarterly costs by CD4 stratum over time, with estimates evaluated at unconditional mean-valued covariates and mean-valued covariates conditional on calendar year and CD4 stratum. Evaluated at unconditional means, costs increased at a diminishing rate over time, with a constant rank ordering between CD4 strata: {(CD4<200mm3) > (CD4: 200–349mm3) > (CD4 unmeasured) > (CD4: 350–499mm3) > (CD4≥500mm3)}. However, at conditional means, the disparity between the CD4<200mm3 stratum and others was much greater; in 2010, quarterly costs were $5781 ($4716, $6846), 3.4 times as high as the CD4: 200–349mm3 stratum ($1703 ($1515, $1892)); p<0.001. Further, higher costs were only observed in quarters in which individuals were at more advanced stages of disease progression (CD4 below 350mm3); quarterly costs were stable or declined for each of the other CD4 strata. Finally, using observed distributions of covariates observed for those prior to HIV care linkage, the unmeasured CD4 stratum was not statistically significantly different from the CD4≥500mm3 stratum in 2010 ($1504 ($1106, $1902) vs. $1307 ($1154, $1460).

Figure 2.

Quarterly non-HAART medical costs by CD4 stratum (1996–2010)

PANEL A: Evaluated at unconditional population-level mean-valued covariates

PANEL B: Evaluated at CD4-stratum and calendar year-specific mean-valued covariates

Discussion

Using population-level data on a population based cohort of HIV-positive individuals accessing and not accessing HAART within a fully subsidized universal health care system, we estimated direct non-HAART costs of medical care. Our results showed that among HIV-positive individuals, periods with high CD4 counts and sustained virologic suppression were associated with substantially lower costs of medical care, due primarily to lower hospitalization costs. Quarterly costs were highest within the final 3 months before mortality, and when accessing HAART, an indicator of optimal engagement in HIV care which likely also represents unmeasured factors that lead to HAART prescription, rather than the direct effect of HAART prescription on non-HAART medical costs..

While the independent effect of being unlinked to HIV care was statistically significantly greater than the CD4>500mm3 group, conditional mean costs (fitted values conditional on CD4-state specific covariates) were similar to periods with CD4>500mm3 a result likely driven by earlier (unmeasured) stages of disease progression prior to linkage to HIV care, and an important distinction for future economic modeling efforts in HIV/AIDS. It is important to note uncontrolled HIV due to poor engagement in HIV care and not being able to access HAART in particular results in the natural course of HIV, resulting in mortality within 10 years of infection[32]. HAART was long considered cost-effective due to the substantial improvements in the duration and quality of life, even before the secondary preventive benefits of treatment were considered[40]; our results on the costs of care for individuals not linked to HIV care should thus be interpreted in the appropriate context.

The relationships between CD4, pVL and non-HAART medical costs have not always been clearly understood and articulated in past analyses, in part because these are commonly combined with the costs of HAART[16,17,40]. Further, little is known regarding the costs medical care for HIV-infected individuals prior to linkage to HIV care and subsequent access to HAART, yet it is important to capture these costs in modeling efforts to inform HAART scale-up. Primary care costs have previously been positively related to disease progression, as later disease stage may necessitate closer physician monitoring and carries a higher probability of inpatient care due to the occurrence of opportunistic infections, adverse drug reactions and related medical complications[3,4,40]. Our findings are consistent with these prior studies, and suggest those not accessing regular HIV care incur health care costs similar to those with low CD4 cell counts.

Our study has also revealed important distinctions in HAART and non-HAART direct medical costs. A previous analysis articulated the relationship between CD4, pVL and the direct costs of HAART[26]. In this study, individuals with sustained virologic suppression tended to have higher treatment costs, controlling for other factors, while those with high CD4 counts tended to have modestly lower drug treatment costs. High CD4 counts are often indicative of early stages of disease progression, whereas sustained virologic suppression (and thus low pVL AUC values) may be obtained at any stage of disease progression, with appropriate use of HAART (often requiring switches to more costly regimens due to the emergence of intolerance or viral resistance) to achieve and sustain suppression. In contrast, sustained virologic suppression, along with higher CD4 counts, were both associated with lower quarterly costs of medical care, consistent with the notion that successful medical management of HIV with HAART can offset the costs of primary care. The distinctions between HAART and non-HAART medical costs are critical to accurately model the economic impact of HIV treatment and prevention efforts.

Otherwise, our results on non-HAART medical costs were highly consistent with at least two prior US-based studies on the costs of HIV/AIDS. Reporting on a study based on the nationwide HIV Research Network, Gebo et al [41] reported mean non-HAART medical costs of $1164 for CD4>500mm3; $1550 for CD4 counts of 351–500mm3; $2108 for CD4 counts of 201–350mm3; and $6154 for CD4<200mm3. A separate model-based analysis on the lifetime costs of care reported non-HAART medical costs of $1493 for CD4>300mm3; $1617 for CD4 counts of 201–300mm3 and $5929 for CD4<200mm3 [42] (all figures adjusted to 2010$US). In contrast, a prior study on a Canadian sample, followed-up from 1997–2006, found similarly increasing non-HAART costs by CD4 stratum, though the levels of costs were lower, with quarterly costs of $709 for CD4>500mm3, $932 for CD4 201–500mm3, and $2712 for CD4<200mm3 in 2006[43] (all costs presented in 2010$CDN). This disparity is at least partially explained by the substantially higher proportion of injection drug users in the present analysis; however further analysis into disparities in HIV care and practice patterns across Canada are called for. Nonetheless, our results appear to be externally valid, with a perhaps surprising degree of consistency in health resource use patterns with US-based studies that was not unduly affected by health care setting.

This analysis has several limitations. First, while the study was based on a population-level registry of antiretroviral treatment dispensation, initiated in 1992 (in the pre-HAART era) and despite similarities to prior findings in US-based studies, caution must be exercised in applying these estimates to other settings given the characteristics of clients, the nature of the HIV epidemic in BC, healthcare delivery policies and current and historical factor prices. If sufficient data is not available, extrapolation using the regression models, and based on localized population and policy conditions, with some adjustment for differential factor prices, may reduce bias. Second, current CD4 and pVL measurements were not always available in all time periods following HAART initiation; a last-observation carried forward approach was used to impute missing observations. Also, CD4 cell counts have been noted to exhibit considerable variability as a result of intra-person temporal fluctuation, for example diurnal variation, as well as from measurement error[43]. This measurement error is likely to be non-differential, leading to measures of association being attenuated towards the null hypothesis. Finally, like all non-experimental studies, our coefficient estimates may have been subject to some degree of bias as a result of unmeasured confounding factors[44].

To conclude, we found that non-HAART direct medical costs were substantially lower for individuals during periods of sustained virologic suppression and high CD4 count. Our results demonstrate that administrative data are an essential source of information for studies of the financial burden of disease. These databases can be significantly augmented by linkage to disease registries to the benefit of economic modeling efforts to inform policy and practice.

Supplementary Material

Key Points for Decision Makers.

Studies capturing direct medical costs for HIV-positive individuals prior to HAART initiation are rare. Evaluated at CD4 state conditional means, we found direct medical costs prior to HAART initiation were similar to those of individuals with CD4>500mm3.

Non-HAART direct medical costs were 3.4 times greater during periods with CD4 cell counts below 200mm3 compared to those with CD4>500mm3, with much of the difference comprised of hospitalization costs.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Jean Nachega for methodological guidance as well as all BCMoH and Vancouver Coastal Health Decision Support Staff involved in data access and procurement, including Monika Lindegger, Clinical Prevention Services, BC Centre for Disease Control; Elsie Wong, Public Health Agency of Canada; Al Cassidy, BC Ministry of Health Registries and Joleen Wright and Karen Luers, Vancouver Coastal Health decision support. This study was funded by the BC Ministry of Health-funded ‘Seek and treat for optimal prevention of HIV & AIDS’ pilot project. Bohdan Nosyk and Viviane Lima are Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholars, and Viviane Lima also holds a CIHR New Investigator award.

Funding: This study was funded by the BC Ministry of Health, as well as through an Avant-Garde Award (No. 1DP1DA026182) from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, at the US National Institutes of Health.

The STOP HIV/AIDS Study Group is comprised of the following

Rolando Barrios, MD, FRCPC, Senior Medical Director, VCH; Adjunct Professor, School of Population and Public Health, UBC.

Patty Daly, MD, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority

Mark Gilbert, Clinical Prevention Services, BC Centre for Disease Control; School of Population & Public Health, University of British Columbia.

Reka Gustafson, MD, Vancouver Coastal Health Authority

Perry RW Kendall, OBC, MBBS, MSc, FRCPC. Provincial Health Officer, British Columbia Ministry of Health; Clinical Professor, Faculty of Medicine UBC

Ciro Panessa, British Columbia Ministry of Health

Nancy South, British Columbia Ministry of Health

Gina McGowan, British Columbia Ministry of Health

Kate Heath, BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: BN conceived the study design, led the econometric analysis and wrote the first draft of the article. VDL, BY and GC all contributed to the analysis. RSH and JSGM contributed to the study design and secured access to the data. All authors provided critical reviews and ultimately approved the submitted draft of the manuscript. BN had full access to the data and is the guarantor for the overall content of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Julio Montaner has received grants from Abbott, Biolytical, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck and ViiV Healthcare. He is also is supported by the Ministry of Health Services and the Ministry of Healthy Living and Sport, from the Province of British Columbia; through a Knowledge Translation Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); and through an Avant-Garde Award (No. 1DP1DA026182) from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, at the US National Institutes of Health. He has also received support from the International AIDS Society, United Nations AIDS Program, World Health Organization, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health Research-Office of AIDS Research, National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases, The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPfAR), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, French National Agency for Research on AIDS & Viral Hepatitis (ANRS), Public Health Agency of Canada. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hogg RS, O’Shaughnessy MV, Gataric N, et al. Decline in deaths from AIDS due to new antiretrovirals. Lancet. 1997;349:1294. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, et al. The survival benefi ts of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:11–19. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozzette SA, Joce G, McCaffrey DF, et al. Expenditures for the care of HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:817–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen RY, Accort NA, Westfall AO, et al. Distribution of health care expenditures for HIV-infected patients. Clinc Infect Dis. 2006;42:1003–10. doi: 10.1086/500453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sloan CE, Champenois K, Choisy P, Losina E, Walensky RP, Schackman BR, Ajana F, Melliez H, Paltiel AD, Freedberg KA, Yazdanpanah Y Cost-Effectiveness of Preventing AIDS Complications (CEPAC) investigators. Newer drugs and earlier treatment: impact on lifetime cost of care for HIV-infected adults. AIDS. 2012 Jan 2;26(1):45–56. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834dce6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nosyk B, Audoin B, Beyrer C, Cahn P, Granich R, Havlir D, Katabira E, Lange C, Lima VD, Patterson T, Strathdee S, Williams B, Montaner JSG. Examining the evidence on the causal effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on transmission of human immunodeficiency virus using the Bradford Hill criteria. AIDS. 2013;27(7):1159–65. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835f1d68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granich R, Gupta S, Suthar A, Smyth C, Hoos D, Vitoria M, Simao M, Hankins C, Schwartlander B, Ridzon R, Bazin B, Williams B, Lo Y-R, McClure C, Montaner J, Hirnschall G on behalf of the ART in Prevention of HIV and TB Research Writing Group. ART in prevention of HIV and TB: Update on current research efforts. Current HIV Research. 2011;9:446–69. doi: 10.2174/157016211798038597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walensky RP, Freedberg KA, Weinstein MC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV testing and treatment in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:S248–54. doi: 10.1086/522546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston KM, Levy AR, Lima VD, Hogg RS, Tyndall MW, Gustafson P, Briggs A, Montaner JSG. Expanding access to HAART: a cost-effective approach for treating and preventing HIV. AIDS. 2010;24:1929–35. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833af85d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendavid E, Young S, Katzenstein DA, Bayoumi AM, Sanders GD, Owens DK. Cost-effectiveness of HIV monitoring strategies in resource-limited settings: A South African analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(17):1910–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eaton JW, Johnson LF, Salomon JA, Bärnighausen T, Bendavid E, et al. HIV treatment as prevention: systematic comparison of mathematical models of the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV incidence in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustafson R, Montaner JSG, Sibbald B. Seek and treat to optimize HIV and AIDS prevention. Can Med Assoc J. 2012;184(18):1971. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long EF, Brandeau ML, Owens DK. The cost-effectiveness and population outcomes of expanded HIV screening and antiretroviral treatment in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(12):778–89. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-12-201012210-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders GD, Bayoumi AM, Sundaram V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening for HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:570–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauskopf J, Kitahata M, Kauf T, et al. HIV Antiretroviral treatment: Early versus later. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:562–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy AR, James D, Johnston KM, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, Harrigan BP, Sobolev B, Montaner JS. The direct costs of HIV/AIDS care. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(3):171–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy A, Johnston K, Annemans L, Tramarin A, Montaner J. The impact of disease stage on direct medical costs of HIV management: a review of the international literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(Suppl 1):35–47. doi: 10.2165/11587430-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nosyk B, Colley G, Chan K, Yip B, Heath K, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, Montaner JSG on behalf of the STOP HIV/AIDS Study Team. Application of case-finding algorithms for identifying individuals with human immunodeficiency virus from administrative data in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manning WG. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. J Health Econ. 1998;17(3):283–95. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. J Health Econ. 1998;17(3):247–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: To transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20(4):461–94. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24(3):465–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basu A, Manning WG. Issues for the next generation of health care cost analyses. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S109–14. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819c94a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF, Telenti A, Benson C, Cahn P, Eron JJ, Günthard HF, Hammer SM, Reiss P, Richman DD, Rizzardini G, Thomas DL, Jacobsen DM, Volberding PA. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2012 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2012;308(4):387–402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogg RS, Heath K, Lima VD, Nosyk B, Kanters S, Wood E, Kerr T, Montaner JS. Disparities in the burden of HIV/AIDS in Canada. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e47260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nosyk B, Montaner JSG, Yip B, Lima VD, Hogg RS on behalf of the STOP HIV/AIDS Study Group. Antiretroviral drug costs and prescription patterns in British Columbia, Canada. 1996–2011 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000097. IN PRESS, Medical Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burd M. BC Ministry of Health. [Accessed: November 2010]. BC Average Cost per Weighted Case (CWC) for CMG+ RIW version 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Acute Care Grouping Methodologies: From Diagnosis Related Groups to Case Mix Groups to Case Mix Groups Redevelopment. [Accessed March 9, 2012];Background paper for the Redevelopment of the Acute Care Inpatietn Grouping Methodology Using ICD-10-CA/CCI Classification Systems. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/products/Acute_Care_Grouping_Methodologies2004_e.pdf.

- 29.Statistics Canada. [Accessed: June 30th, 2014];Consumer Price Index, Historical Summary (1994–2013) http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/econ46a-eng.htm.

- 30.Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90016-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degenhardt L, Randall D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, Burns L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009 Nov 1;105(1–2):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.021. Epub 2009 Jul 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellors JW, Munoz A, Giorgi JV, Margolick JB, Tassoni CJ, Gupta P, Kingsley LA, Todd JA, Saah AJ, Detels R, Phair JP, Rinaldo CR., Jr Plasma viral load and CD4+ lymphocytes as prognostic markers of HIV-1 infection. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(12):946–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-12-199706150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien WA, Hartigan PM, Martin D, Esinhart J, Hill A, Benoit S, Rubin M, Simberkoff MS, Hamilton JD. Changes in plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4+ lymphocyte counts and the risk of progression to AIDS. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(7):426–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lima VD, Zhang W, Yip B, Chan K, Nosyk B, Kanters S, Kozai T, Montaner JSG. Assessing the effectiveness of antiretroviral regimens in cohort studies involving HIV-positive injection drug users. AIDS. 2012;26(12):1491–500. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283550b68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park R. Estimation with heteroskedastic error terms. Econometrica. 1966;34:888. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. 1967;1:221–33. [Google Scholar]

- 37.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–30. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nachega JB, Leisegang R, Bishai D, Nguyen H, Hislop M, Cleary S, Regensberg L, Maartens G. Association of antiretroviral therapy adherence and health care costs. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):18–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belotti F, Deb P, Manning WG, Norton EC. Tpm: Estimating two-part models. The Stata journal. 2012;vv(ii):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walensky R. Cost-effectiveness of HIV interventions: From cohort studies and clinical trials to policy. Top HIV Med. 2009;17(4):130–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gebo KA, Fleishman JA, Conviser R, et al. Contemporary costs of HIV healthcare in the HAART era. AIDS. 2010;24:2705–2715. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f3c14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schackman BR, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, et al. The lifetime cost of current human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States. Medical Care. 2006;44:990–997. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228021.89490.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krentz HB, Gill MJ. Cost of medical care for HIV-infected patients within a regional population from 1997 to 2006. HIV Medicine. 2008;9:721–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoover DR, Graham NM, Chen B, Taylor JM, Phair J, Zhou SY, Munoz A. Effect of CD4+ cell count measurement variability on staging HIV-1 infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 1992;5(8):794–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359:248–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.