Long-term persistence of varicella antibodies was strongly associated with administration of 2 varicella vaccines in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus–infected children. Vaccination after ≥3 months of combination antiretroviral therapy and duration of such therapy were also determinants of vaccine immunogenicity.

Keywords: varicella, vaccine, antibodies, HIV, perinatal

Abstract

Background. Two doses of live-attenuated varicella-zoster vaccine are recommended for human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1)–infected children with CD4% ≥15%. We determined the prevalence and persistence of antibody in immunized children with perinatal HIV (PHIV) and their association with number of vaccinations, combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), and HIV status.

Methods. The Adolescent Master Protocol is an observational study of children with PHIV and perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (PHEU) children conducted at 15 US sites. In a cross-sectional analysis, we tested participants' most recent stored sera for varicella antibody using whole-cell and glycoprotein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Seropositivity predictors were identified using multivariable logistic regression models and C statistics.

Results. Samples were available for 432 children with PHIV and 221 PHEU children; 82% of children with PHIV and 97% of PHEU children were seropositive (P < .001). Seropositivity after 1 vaccine dose among children with PHIV and PHEU children was 100% at <3 years (both), 73% and 100% at 3–<7 years (P < .05), and 77% and 97% at ≥7 years (P < .01), respectively. Seropositivity among recipients of 2 vaccine doses was >94% at all intervals. Independent predictors of seropositivity among children with PHIV were receipt of 2 vaccine doses, receipt of 1 dose while on ≥3 months of cART, compared with none (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 14.0 and 2.8, respectively; P < .001 for overall dose effect), and in those vaccinated ≥3 years previously, duration of cART (aOR: 1.29 per year increase, P = .02).

Conclusions. Humoral immune responses to varicella vaccine are best achieved when children with PHIV receive their first dose ≥3 months after cART initiation and maintained by completion of the 2-dose series and long-term cART use.

A universal varicella (VZV) childhood immunization program that recommended a single dose of varicella vaccine at 12–18 months of age was implemented in the United States in 1995. Since 2006, a 2-dose series, given at age 12–15 months and age 4–6 years, has been recommended for all children [1–4]. For human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected children, the recommendation is 2 vaccinations, at least 3 months apart [5].

VZV can cause severe, sometimes fatal disease in immunocompromised children with an extensive rash, which can be hemorrhagic, and complications such as pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis [6–8]. Herpes zoster (HZ) also can cause severe complications, including progressive outer retinal necrosis [9–11] and trigeminal nerve involvement, resulting in ophthalmitis and keratitis [12]. These complications underscore the importance of immunizing HIV-infected children against varicella.

Because of concerns regarding safety of live-attenuated vaccines, the VZV vaccine was initially recommended for HIV-infected children with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clinical and immunologic categories N1 or A1 and CD4 T-lymphocytes ≥25% [13–15]. In 2007, its use was extended to HIV-infected children with CD4 T-lymphocytes ≥15% [5, 16].

Prospective clinical trials in children infected with perinatal HIV (PHIV) that have examined the safety and immunogenicity of the VZV vaccine [13, 16–19] are limited by small sample sizes and have not specifically examined the role of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) on vaccine immunogenicity. Proportions of children that seroconverted 6–12 weeks after 1 vaccination ranged 12%–62% [13, 16, 17, 19] and, in 1 study, fell from 62% to 33% 1 year later [17]. After 2 vaccine doses, 59%–79% of children seroconverted 6–12 weeks later [13, 16, 18, 19]. Proportions seropositive at 1 year ranged 43%–65% [16].

Levin et al reported vaccine efficacy of 79% using a composite endpoint of VZV-specific antibodies and/or cell-mediated immunity [16]. A subsequent retrospective study of children with PHIV at 2 centers in the United States reported an efficacy of 82% based on a clinical diagnosis of varicella [20].

These data suggest that a substantial proportion of children with PHIV may remain at risk of breakthrough varicella despite vaccination. A better understanding of the optimal manner in which to immunize this population is needed, particularly in the cART era.

The aim of this study was to evaluate persistence of VZV-specific antibodies after vaccination with 1 or 2 doses of VZV vaccine and to identify determinants of varicella seropositivity in a large cohort of children and adolescents with PHIV and also in perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (PHEU) children.

METHODS

Study Population

The Adolescent Master Protocol (AMP), a component of the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study, is an ongoing prospective cohort study designed to evaluate long-term effects of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy (ART) among children with PHIV. It enrolled 451 children with PHIV and 227 PHEU children aged 7–16 years from March 2007 to November 2009 at 15 sites in the United States, including Puerto Rico. Participants were required to have complete medical history of ART use, plasma HIV RNA concentrations, and lymphocyte subset measurements since birth. Repository sera were frozen at −70°C. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site and at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Informed consent was obtained from the parent or legal guardian, and assent was obtained from child participants, per local institutional review board guidelines.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible participants were those with repository serum specimens available for varicella antibody testing as of 31 October 2012. Their last VZV vaccination had to be >21 days before the date the specimen was obtained.

Data Elements

Demographic and clinical characteristics of interest included age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), vaccination history, plasma HIV RNA, CD4%, CDC clinical classification for HIV disease [14, 15], and prescribed ART. BMI was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2) and expressed as z scores for age and sex [21]. The area-under-the-curve (AUC) viral load from the last vaccine dose to serologic testing, expressed as log10 copy-years, was calculated using the trapezoidal method [22]. To calculate a time-averaged version of this measure, the AUC was subsequently divided by the years of follow-up time. cART was defined as a regimen consisting of at least 3 antiretroviral drugs from at least 2 different drug classes, and the era of cART was defined as the period from 1998 on [23].

Serologic Testing

Serum specimens were analyzed by the National VZV Laboratory at the CDC using a 2-step testing algorithm. All samples were first tested using an immunoglobulin G whole-infected cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (wcELISA). Samples testing negative/equivocal were retested using glycoprotein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (gpELISA), a highly sensitive and specific method developed at the CDC using highly purified VZV glycoproteins obtained through a material transfer agreement with Merck and Co (Valley Forge, Pennsylvania) [24, 25]. Participants were seropositive if they had a positive result from either test.

Statistical Analysis

Proportions of seropositive subjects were estimated with 95% exact binomial confidence intervals (CIs) and compared between subjects with PHIV and PHEU subjects using Fisher's exact test. Estimates were further stratified by number of vaccine doses and the time from last vaccination to serologic testing and compared using Fisher's exact test. Demographic and clinical characteristics, HIV severity measures, and ART at the time of last varicella vaccine dose and date of specimen were compared among subjects with PHIV by varicella antibody status using Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. We hypothesized that the relationship between varicella seropositivity and years from last dose to specimen date may be modified by the number of vaccine doses and timing of cART. We therefore compared the effect on varicella seropositivity of the interval from last vaccine dose to specimen date in 3 vaccine dose–cART groups: receipt of 1 vaccination after ≥3 months of cART; receipt of 1 vaccination with <3 months of cART; and receipt of 2 vaccinations regardless of cART. Ninety-five percent exact binomial CIs and Fisher's exact test were used for statistical inference in these comparisons.

To identify independent predictors of varicella seropositivity among subjects with PHIV, univariable and multivariable logistic regression models that included all covariables were performed to generate C statistics. To further identify a key set of covariables that would be most predictive of varicella seropositivity among subjects with PHIV who received 1 or 2 vaccine doses and had at least 3 years between their last dose and specimen date, univariable logistic regression models were performed using this subgroup. A multivariable predictive logistic regression model was then built by first including the vaccine dose–cART grouping variable and subsequently including all other covariables significant at α = .10 with a C statistic ≥0.60 from univariable models. To avoid possible collinearity issues, only the strongest predictor within each set of CD4% and viral load parameters meeting the above selection criteria was included in the multivariable model. This multivariable model building process was also repeated for subjects with PHIV who had only 1 vaccine dose and at least 3 years between their vaccination and specimen date. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Cohort

There were 653 subjects (432 PHIV and 221 PHEU) whose birth years ranged from 1991 to 2002 (Supplementary Table 1). Compared with PHEU subjects, more subjects with PHIV were black, fewer were Hispanic, and more were living in poverty. At the time their specimens were obtained for testing, subjects with PHIV were older and had a lower BMI z score than PHEU subjects. Overall, fewer subjects with PHIV compared with PHEU subjects received the VZV vaccine, with 38% vs 18% unvaccinated, 26% vs 25% having received 1 dose, and 34% vs 55% having received 2 doses, respectively (P < .001). Subjects with PHIV were older than PHEU subjects at the time of their first vaccine (median: 4.7 vs 1.5 years; P < .001), had a shorter interval between first and second vaccinations (median: 3.9 vs 6.1 years; P < .001), and had more documented HZ episodes (10% vs 0%; P < .001). The median interval from last vaccine dose to sample collection was longer for subjects with PHIV than PHEU subjects (4.2 vs 3.5 years; P < .05).

Varicella Seroprevalence Among PHIV and PHEU Subjects

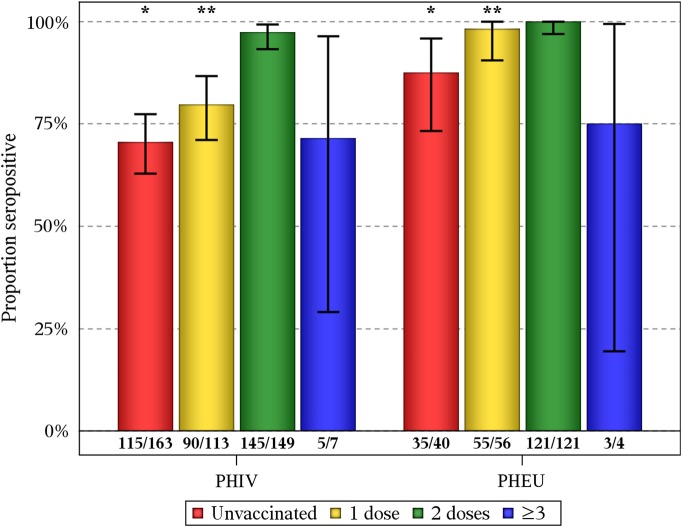

Of the 653 subjects tested, 491 (75.2%) tested positive by wcELISA. Among those testing negative, 78 (11.9% of all subjects) then tested positive by gpELISA. Overall, 87% of the cohort was seropositive to varicella, with a seroprevalence among subjects with PHIV of 82% (95% CI, 78%–86%), significantly lower than among PHEU subjects (97%; 95% CI, 94%–99%). For subjects who had not received the vaccine, seroprevalence was again significantly lower among subjects with PHIV (71%; 95% CI, 63%–77%) than PHEU subjects (88%; 95% CI, 73%–96%) (Figure 1). Seroprevalence among those who received 1 vaccination was 80% (95% CI, 71%–87%) for subjects with PHIV and 98% (95% CI, 90%–100%) for PHEU subjects. Seroprevalence among those who received 2 vaccinations was 97% (95% CI, 93%–99%) for subjects with PHIV and 100% (95% CI, 97%–100%) for PHEU subjects.

Figure 1.

Proportion seropositive for varicella by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status and the number of varicella vaccine doses received. Vertical bars are exact binomial 95% confidence intervals. Numbers at the bottom of the bars represent seropositive subjects (numerator) and subjects in each category (denominator). Fisher's exact test for subjects with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV) vs perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected subjects (PHEU): *P < .05, **P < .001.

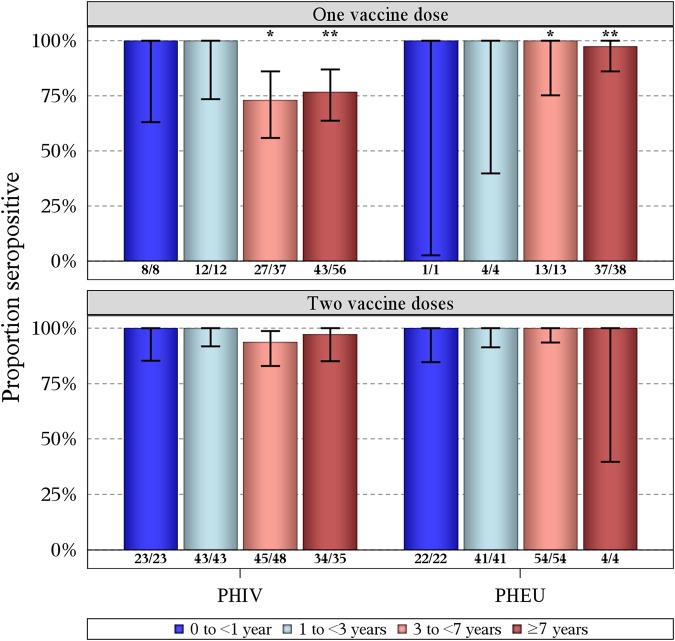

Persistence of Varicella Antibodies in Subjects With PHIV and PHEU Subjects Who Received 1 and 2 Vaccines

Antibody persistence was assessed by segmenting the study population according to time interval from the last vaccination to specimen collection date. All subjects with PHIV and PHEU subjects tested <3 years from the last vaccine dose were seropositive, regardless of whether they received 1 or 2 vaccines (Figure 2). Among subjects who received 1 vaccine, fewer subjects with PHIV than PHEU subjects were seropositive when tested at both 3–<7 years (73% vs 100%; P < .05) and ≥7 years (77% vs 97%; P < .01), respectively, following vaccination. In contrast, there were no significant differences between subjects with PHIV and PHEU subjects who received 2 vaccines at either time interval following vaccination. Therefore, we further examined the impact of duration of cART at the time of vaccination on varicella serostatus of subjects with PHIV who received 1 vaccine (Figure 3). Seroprevalence was significantly lower for recipients of 1 vaccine after <3 months of cART than for those who received 2 doses but did not differ from recipients of 1 vaccine after ≥3 months of cART at both time intervals.

Figure 2.

Proportion seropositive for varicella among subjects who received 1 and 2 doses of varicella vaccine by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status and years from last vaccine dose to specimen date. Vertical bars are exact binomial 95% confidence intervals. Numbers at the bottom of the bars represent varicella seropositive subjects (numerator) and subjects in each category (denominator). Fisher's exact test for subjects with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV) vs perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected subjects (PHEU): *P < .05, **P < .01.

Figure 3.

Proportion seropositive for varicella among subjects with perinatal human immunodeficiency virus (PHIV) who received 1 and 2 varicella vaccine doses by years from last vaccine dose to specimen date and combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) use. Vertical bars are exact binomial 95% confidence intervals. Numbers at the bottom of the bars represent varicella seropositive subjects (numerator) and subjects in each category (denominator). Fisher's exact test for 1 dose not on ≥3 months cART vs 2 doses: *P < .01.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Subjects With PHIV by VZV Antibody Status

Among all of the demographic characteristics measured for the 432 subjects with PHIV, only annual household income differed by VZV serostatus, with seropositive subjects more likely to come from a household with a higher income (Table 1). The likelihood of being VZV seropositive increased with the number of vaccine doses received for all subjects with PHIV and also among those on at least 3 cumulative months of cART when vaccinated (P < .001 for both). Among characteristics measured at the date of specimen draw, seropositivity was positively associated with higher CD4%, higher lifetime nadir CD4%, and higher nadir CD4% beginning from last vaccine dose and negatively associated with more years from last vaccine dose, being CDC class C, and higher AUC viral load beginning from last vaccine dose for vaccinated subjects. Seropositivity at the time of testing was marginally associated with more cumulative years on cART. For participants who received at least 1 vaccine, seropositivity was also positively associated with older age, later calendar year of dose, and more cumulative years on cART and negatively associated with a higher viral load, all as measured at the time of participants' last vaccine.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Subjects with Perinatal Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection by Varicella Serostatus

| Characteristics | Total (N = 432) | Assay Result |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 355) | Negative (n = 77) | |||

| Birth cohort | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | '96 ('94, '98) | '96 ('94, '98) | '95 ('94, '98) | .43a |

| ≥1998 | 129 | 109 (31%) | 20 (26%) | .49b |

| Female | 231 | 197 (55%) | 34 (44%) | .08b |

| Black race | 291 | 240 (68%) | 51 (66%) | .79b |

| Missing | 3 | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 107 | 82 (23%) | 25 (32%) | .11b |

| Missing | 3 | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Caregiver highest education level | .49b | |||

| Did not graduate high school | 154 | 130 (37%) | 24 (31%) | |

| High school | 138 | 108 (30%) | 30 (39%) | |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 68 | 56 (16%) | 12 (16%) | |

| 4-year college degree or higher | 69 | 59 (17%) | 10 (13%) | |

| Missing | 3 | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Annual household income >$20 000 | 217 | 187 (53%) | 30 (39%) | .03b |

| Missing | 27 | 22 (6%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Ever had documented varicella (chickenpox) | 60 | 51 (14%) | 9 (12%) | .72b |

| Ever had documented herpes zoster (shingles) | 44 | 40 (11%) | 4 (5%) | .15b |

| Total number of vaccine doses | <.001b | |||

| Unvaccinated | 163 | 115 (32%) | 48 (62%) | |

| 1 dose | 113 | 90 (25%) | 23 (30%) | |

| 2 doses | 149 | 145 (41%) | 4 (5%) | |

| >3 doses | 7 | 5 (1%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Number of doses while on >3 months cARTc | <.001b | |||

| 0 | 225 | 163 (46%) | 62 (81%) | |

| 1 | 102 | 91 (26%) | 11 (14%) | |

| >2 | 105 | 101 (28%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Age at first cART, y | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.8 (0.8, 5.4) | 2.7 (0.8, 5.5) | 3.2 (1.1, 5.3) | .41a |

| Missing/never on cART | 16 | 13 (4%) | 3 (4%) | |

| At last vaccine dose | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 8.0 (4.2, 11.9) | 8.6 (4.4, 12.0) | 4.6 (2.2, 7.7) | .003a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 163 | 115 (32%) | 48 (62%) | |

| Year of dose | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | '06 ('01, '07) | '07 ('01, '08) | '02 ('00, '03) | <.001a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 163 | 115 (32%) | 48 (62%) | |

| Nadir CD4% | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 22.0 (15.7, 29.0) | 22.0 (15.0, 29.0) | 23.3 (17.0, 29.0) | .57a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 183 | 129 (36%) | 54 (70%) | |

| CD4% | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 35.0 (30.0, 41.0) | 36.0 (30.0, 41.0) | 33.0 (23.0, 39.0) | .23a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 183 | 129 (36%) | 54 (70%) | |

| Viral load, log10 copies/mL | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.6 (1.7, 3.1) | 2.4 (1.7, 3.0) | 3.5 (2.6, 4.1) | <.001a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 187 | 134 (38%) | 53 (69%) | |

| Cumulative years on cART | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 3.9 (1.2, 7.4) | 4.3 (1.7, 7.9) | 1.3 (0.0, 3.1) | <.001a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 163 | 115 (32%) | 48 (62%) | |

| At most recent specimen | ||||

| Years from last dose to last specimen | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 4.2 (2.2, 8.2) | 3.7 (2.0, 8.0) | 8.0 (5.2, 8.7) | <.001a |

| ≥3 y | 179 | 151 (43%) | 28 (36%) | <.001b |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 163 | 115 (32%) | 48 (62%) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 14.0 (11.7, 15.9) | 14.0 (11.7, 16.1) | 14.2 (11.5, 15.5) | .59a |

| BMI z score | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.32 (−0.44, 1.19) | 0.32 (−0.40, 1.19) | 0.29 (−0.69, 1.17) | .56a |

| Missing | 1 | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| CDC class C | 108 | 81 (23%) | 27 (35%) | .03b |

| Nadir CD4%, last dose to last specimen | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 27.1 (18.5, 33.0) | 28.5 (21.0, 33.2) | 17.0 (12.0, 24.0) | <.001a |

| <15% | 37 | 25 (7%) | 12 (16%) | <.001b |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 166 | 118 (33%) | 48 (62%) | |

| Nadir CD4% | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 18.0 (11.8, 24.0) | 18.0 (12.0, 24.1) | 16.0 (9.0, 22.0) | .02a |

| CD4% | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 34.0 (25.9, 39.0) | 34.0 (26.0, 40.0) | 32.0 (23.0, 35.8) | .005a |

| AUC of viral load, log10 copy-years, last dose to last specimend | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 8.3 (4.2, 17.2) | 7.5 (3.7, 16.6) | 21.4 (14.0, 25.7) | <.001a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 187 | 134 (38%) | 53 (69%) | |

| Time-averaged AUC of viral load, log10 copy-years, last dose to last specimend | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.2 (1.8, 3.0) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.8) | 3.2 (2.6, 3.8) | <.001a |

| Missing/never vaccinated | 187 | 134 (38%) | 53 (69%) | |

| Viral load, log10 copies/mL | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.9 (1.7, 3.1) | 1.9 (1.7, 3.1) | 2.2 (1.7, 3.6) | .13a |

| On >3 months cART | 352 | 290 (82%) | 62 (81%) | .87b |

| Cumulative years on cART | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 9.6 (6.5, 11.6) | 9.7 (6.8, 11.7) | 8.8 (5.5, 10.8) | .06a |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

a Wilcoxon test.

b Fisher's exact test.

c The number of vaccine doses received where each dose was received while on any consecutive series of cART regimens for at least 3 months immediately prior to and up through the day of dose receipt.

d Calculated AUC using the trapezoidal method. First value, if not measured on same day as start point, was estimated using linear interpolation from the flanking readings of the start day. Last value, if not measured on same day as the end point, was estimated by carrying the last known value forward. To calculate a time-averaged version of this measure, the AUC was subsequently divided by the years of follow-up time.

Determinants of Varicella Seropositivity in Subjects With PHIV Following Varicella Vaccination

Results of the first multivariable logistic regression model are for all subjects with PHIV with complete data (Table 2; N = 390). Compared with no vaccine, 2-dose vaccine recipients were more likely to be seropositive (aOR: 14; 95% CI, 4.6–42.6), as were 1-dose vaccine recipients receiving ≥3 months of cART at the time of vaccination (aOR: 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1–7.1). One-dose vaccine recipients not on ≥3 months of cART were not (aOR: 1.0; 95% CI, .4–2.5). Subjects with a history of HZ were also more likely to be seropositive (aOR: 5.3; 95% CI, 1.6–17.9). The second multivariable model is for the subset of subjects with PHIV with at least a 3-year interval between the last vaccination and the date of specimen tested and with complete data (Supplementary Table 2; N = 137). This analysis was driven by our finding of significantly lower seroprevalence beyond 3 years. Seven predictors were included with a collective C statistic of 0.86. The odds of seropositivity increased by 1.29-fold (95% CI, 1.05–1.59) for every 1-year increase in cumulative years on cART as of the specimen date, after controlling for all other model covariables.

Table 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Predictive Model Results for Varicella Seropositivity Among Subjects with Perinatal Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection at Last Specimen Date and With Complete Data (N = 390)

| Characteristic | Univariable Model |

Multivariable Modela (overall c statistic = 0.834) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | C Statisticb | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Total vaccine doses received | <.001 | ||||||

| 1 (not on >3 months cART) (vs none) | 0.8 | .4–1.8 | <.001 | 0.724 | 1.0 | .4–2.5 | |

| 1 (on >3 months cART) (vs none) | 2.5 | 1.1–5.4 | 2.8 | 1.1–7.1 | |||

| 2 (vs none) | 13.3 | 4.6–38.4 | 14.0 | 4.6–42.6 | |||

| ≥3 (vs none) | 1.0 | .2–5.4 | 1.3 | .2–8.3 | |||

| Birth cohort ≥1998 (vs <1998) | 1.38 | .76–2.51 | .29 | 0.533 | 2.71 | .97–7.58 | .06 |

| Female (vs male) | 1.28 | .76–2.15 | .36 | 0.530 | 1.33 | .71–2.48 | .37 |

| Black race (vs non-black) | 1.17 | .68–2.01 | .57 | 0.518 | 0.27 | .03–2.46 | .24 |

| Hispanic ethnicity (vs non-Hispanic) | 0.60 | .34–1.05 | .07 | 0.552 | 0.12 | .01–1.20 | .07 |

| Caregiver highest education level | .40 | ||||||

| Did not graduate high school | Referent | Referent | .44 | 0.555 | Referent | Referent | |

| High school | 0.62 | .33–1.15 | 0.57 | .27–1.20 | |||

| Some college or 2-year degree | 0.90 | .38–2.11 | 0.52 | .19–1.42 | |||

| 4-year college degree or higher | 0.95 | .42–2.16 | 0.56 | .20–1.52 | |||

| Income >$20 000/year (vs ≤$20 000) | 1.87 | 1.10–3.17 | .02 | 0.577 | 1.60 | .83–3.07 | .16 |

| Age at first cART (1 y increase) | 0.97 | .91–1.04 | .43 | 0.535 | 1.07 | .89–1.28 | .49 |

| Ever documented herpes zoster event (vs not) | 2.12 | .73–6.15 | .17 | 0.529 | 5.3 | 1.6–17.9 | .007 |

| Covariables below assessed at date of most recent specimen | |||||||

| Age (1 y increase) | 1.04 | .95–1.14 | .40 | 0.526 | 1.16 | .91–1.47 | .23 |

| BMI z score (1 unit increase) | 1.13 | .91–1.42 | .27 | 0.533 | 1.18 | .91–1.54 | .21 |

| CDC class C (vs not) | 0.56 | .32–.97 | .04 | 0.561 | 0.62 | .31–1.24 | .18 |

| Nadir CD4% (1% increase) | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | .049 | 0.572 | 0.99 | .95–1.04 | .79 |

| CD4% (1% increase) | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | .003 | 0.611 | 1.04 | .99–1.08 | .09 |

| Viral load (1 log10 copies/mL increase) | 0.81 | .64–1.03 | .09 | 0.535 | 0.88 | .59–1.29 | .51 |

| On >3 months cART (vs not) | 0.90 | .43–1.87 | .77 | 0.507 | 0.39 | .12–1.22 | .10 |

| Cumulative years on cART (1 y increase) | 1.08 | 1.00–1.16 | .048 | 0.585 | 1.12 | .94–1.35 | .20 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CI, confidence interval.

a The multivariable model analysis set of subjects was restricted to those with complete information on all of the variables tested in univariable models.

b C statistic: the area under the curve in a receiver operating characteristic curve that measures predictive ability ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 signifying perfect sensitivity and specificity of a regression model to predict the outcome, 0.5 indicating no predictive ability, and 0 representing perfect misclassification.

A third multivariable model was developed for recipients of 1 vaccine in subjects with PHIV with at least 3 years between their dose and specimen and complete covariable data (N = 66; data not shown) because this group was at the greatest risk of being seronegative. Cumulative years on cART up to the time of specimen was marginally predictive of seropositivity (OR: 1.37; 95% CI, .99–1.90; P = .06). Sensitivity analyses for the multivariable models using all subjects with data available for significant covariables gave similar OR estimates (<12% changes).

DISCUSSION

The stepwise implementation of VZV vaccine in the United States from a 1- to 2-dose series between 1995 and 2006 allowed us to describe varicella serostatus in relation to number of doses received and time since vaccination among children with PHIV and PHEU children. Overall, seropositivity was significantly lower in subjects with PHIV compared with PHEU subjects. While all subjects with PHIV and PHEU subjects who received 1 vaccination had an induced antibody response in the short term, seroprevalence beyond 3 years was approximately 25% lower among subjects with PHIV. With a second vaccination, both subjects with PHIV and PHEU subjects had a seroprevalence >94% at all intervals studied.

Clinical trials examining humoral responses after administration of VZV vaccine to children with PHIV have shown suboptimal seroconversion rates, even after a 2-dose series. Findings in this cohort of subjects with PHIV differ in several important aspects. There was 100% prevalence of varicella antibodies within 3 years of vaccination, regardless of number of vaccinations received. A 2-dose vaccine series resulted in very high persistence of antibodies extending up to, and beyond, 7 years—a much longer interval after vaccination than previous studies. Persistence of antibodies in subjects with PHIV after 1 vaccination was also substantially higher, although still lower beyond 3 years than what is found in healthy children. Kuter et al reported persistence of VZV-specific antibodies in 86.9%–95.3% at 1–9 years following a dose of VZV vaccine in healthy children aged 1–12 years [26], similar to our PHEU children who received 1 vaccine. This is the first study to show that administration of 2 doses of VZV vaccine is a robust, durable, and independent predictor of seropositivity in children with PHIV.

The AMP cohort consists of subjects with PHIV who survived into adolescence on ART, 78% with CD4 ≥25% and 68% with suppressed viral load at entry [27]. Their relatively healthy immunologic status is probably the main reason why we observed such reassuringly high prevalence and persistence of antibodies to varicella following vaccination. Apart from the studies by Levin et al, which used a sensitive fluorescent-antibody-to-membrane-antigen assay for varicella antibody testing [13, 16], the less sensitive enzyme immunoassays used in the other previous studies also likely contributed to their lower estimates.

A review by Sutcliffe et al described low levels of immunity in HIV-infected children vaccinated prior to treatment, response to revaccination after initiating cART, and gaps in our knowledge of how best to maintain immunity thereafter [28]. Of the replicating vaccines discussed in the review, only 1 varicella study was cited [16], highlighting lack of data for this vaccine. Our study defines the role of cART in the immune response to VZV vaccine: receipt of 1 vaccine was a determinant of an antibody response, but only in those on cART for ≥3 months at the time of vaccination. Further, 3 years after the last vaccination when loss of antibodies occurred in subjects with PHIV, the cumulative number of years participants had been on cART at the time of testing was also an independent determinant, with an approximately 30% increase in odds of remaining positive for every year of cART use. Collectively, these data demonstrate that initiating cART prior to vaccinating and maintaining children on cART are important in the short- and long-term humoral response to VZV vaccine.

Reports showing that early treatment with cART after HIV infection enhances CD4 T-cell recovery [29] and results in normal development and function of memory B cells [30–32] further support an optimal and durable immune response to vaccine antigens as an additional benefit to initiating cART as soon as possible in vertically HIV-infected infants.

The natural history of varicella in HIV-infected children is characterized by a high incidence of HZ, with rates >15 times the general population [33, 34]. Uncommon with widespread use of cART, it still occurs more frequently than in immune-competent children [20], and its association with antibody persistence is a reflection of endogenous boosting caused by reactivation of latent virus.

The large sample size and representation of patients from centers across the nation are a particular strength of this study. This large sample also allowed us to estimate seroprevalence among different segments of the cohort, defined by number of vaccinations administered and time from last vaccination to specimen collection. The use of our wcELISA/gpELISA 2-step algorithm increased testing sensitivity, identifying presence of antibodies in a further 12% of subjects who would otherwise have tested negative. There are limitations worth noting. Individual participants were not followed longitudinally to evaluate persistence or loss of antibody. Caution should be exercised in extrapolating these findings to immunity against chickenpox, as such immunity comprises both cellular- and antibody-specific responses. Indeed T-cell–mediated immunity plays a central role in protecting against and recovering from chickenpox and HZ [35]. Waning with advancing age or immune-suppression allows reactivation of latent virus in sensory ganglia [35, 36]. Nevertheless, gpELISA has been validated using a panel of sera from children aged 12–18 months that were defined as true negative (before vaccination) and true positive (after vaccination) and is correlated with protection against disease [5, 24].

Early initiation, as soon as the diagnosis is established in newborns with PHIV, and lifelong treatment with cART is the standard of care in the United States. Our data provide strong support for this approach and for use of the 2-dose varicella vaccine program in children with PHIV—a practice that will produce a durable humoral immune response to this vaccine-preventable disease. Additional boosting doses of varicella vaccine in children with PHIV on cART are therefore not supported by the current evidence.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the children and families for their participation in Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS), and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of PHACS.

The following institutions (in alphabetical order), clinical site investigators, and staff participated in conducting PHACS Adolescent Master Protocol in 2014: Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago: Ram Yogev, Margaret Ann Sanders, Kathleen Malee, Scott Hunter; Baylor College of Medicine: William Shearer, Mary Paul, Norma Cooper, Lynnette Harris; Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center: Murli Purswani, Mahboobullah Baig, Anna Cintron; Children's Diagnostic & Treatment Center: Ana Puga, Sandra Navarro, Patricia Garvie, James Blood; Children's Hospital, Boston: Sandra Burchett, Nancy Karthas, Betsy Kammerer; Jacobi Medical Center: Andrew Wiznia, Marlene Burey, Molly Nozyce; Rutgers–New Jersey Medical School: Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica, Susan Adubato; St. Christopher's Hospital for Children: Janet Chen, Maria Garcia Bulkley, Latreaca Ivey, Mitzie Grant; St. Jude Children's Research Hospital: Katherine Knapp, Kim Allison, Megan Wilkins; San Juan Hospital/Department of Pediatrics: Midnela Acevedo-Flores, Heida Rios, Vivian Olivera; Tulane University Health Sciences Center: Margarita Silio, Medea Jones, Patricia Sirois; University of California, San Diego: Stephen Spector, Kim Norris, Sharon Nichols; University of Colorado Denver Health Sciences Center: Elizabeth McFarland, Alisa Katai, Jennifer Dunn, Suzanne Paul; University of Miami: Gwendolyn Scott, Patricia Bryan, Elizabeth Willen.

B. K. and T.-J. Y. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conception and design of the study: M. U. P., B. K., T.-J. Y., and R. Y. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of manuscript: M. U. P., B. K., T.-J. Y., and R. Y. Revision of manuscript: All authors. Statistical analysis: B. K., and T.-J. Y. Administrative, technical, or material support: All authors. Supervision of the study: M. U. P., D. S. S., R. Y., and R. B. V. D.

Disclaimer. The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health or US Department of Health and Human Services.

Financial support. The PHACS was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with co-funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Office of AIDS Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HD052102; Principal Investigator: George Seage; Project Director: Julie Alperen) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (HD052104; Principal Investigator: Russell Van Dyke; Co-Principal Investigator: Kenneth Rich; Project Director: Patrick Davis). Data management services were provided by Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation (Principal Investigator: Suzanne Siminski), and regulatory services and logistical support were provided by Westat, Inc (Principal Investigator: Julie Davidson).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS), Robert H. Lurie, Ram Yogev, Margaret Ann Sanders, Kathleen Malee, Scott Hunter, William Shearer, Mary Paul, Norma Cooper, Lynnette Harris, Murli Purswani, Mahboobullah Baig, Anna Cintron, Ana Puga, Sandra Navarro, Patricia Garvie, James Blood, Sandra Burchett, Nancy Karthas, Betsy Kammerer, Andrew Wiznia, Marlene Burey, Molly Nozyce, Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica, Susan Adubato, Janet Chen, Maria Garcia Bulkley, Latreaca Ivey, Mitzie Grant, Katherine Knapp, Kim Allison, Megan Wilkins, Midnela Acevedo-Flores, Heida Rios, Vivian Olivera, Margarita Silio, Medea Jones, Patricia Sirois, Stephen Spector, Kim Norris, Sharon Nichols, Elizabeth McFarland, Alisa Katai, Jennifer Dunn, Suzanne Paul, Gwendolyn Scott, Patricia Bryan, and Elizabeth Willen

References

- 1.Prevention of varicella. Update recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 1999; 48(RR-6):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Varicella surveillance practices—United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006; 55:1126–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marin M, Meissner HC, Seward JF. Varicella prevention in the United States: a review of successes and challenges. Pediatrics 2008; 122:e744–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guris D, Jumaan AO, Mascola L et al. Changing varicella epidemiology in active surveillance sites—United States, 1995–2005. J Infect Dis 2008; 197(suppl 2):S71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marin M, Guris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF. Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2007; 56(RR-4):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corti M, Trione N, Villafane MF, Risso D, Yampolsky C, Mamanna L. Acute meningoencephalomyelitis due to varicella-zoster virus in an AIDS patient: report of a case and review of the literature. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2011; 44:784–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lechiche C, Le Moing V, Francois Perrigault P, Reynes J. Fulminant varicella hepatitis in a human immunodeficiency virus infected patient: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 2006; 38:929–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popara M, Pendle S, Sacks L, Smego RA Jr, Mer M. Varicella pneumonia in patients with HIV/AIDS. Int J Infect Dis 2002; 6:6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gore DM, Gore SK, Visser L. Progressive outer retinal necrosis: outcomes in the intravitreal era. Arch Ophthalmol 2012; 130:700–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin PD, Kurup SK, Fischer SH et al. Progressive outer retinal necrosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: successful management with intravitreal injections and monitoring with quantitative PCR. J Clin Virol 2007; 38:254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purdy KW, Heckenlively JR, Church JA, Keller MA. Progressive outer retinal necrosis caused by varicella-zoster virus in children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 22:384–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilhelmus KR, Hamill MB, Jones DB. Varicella disciform stromal keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1991; 111:575–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin MJ, Gershon AA, Weinberg A et al. Immunization of HIV-infected children with varicella vaccine. J Pediatr 2001; 139:305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 1992; 41(RR-17):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1994 revised guidelines for the performance of CD4+ T-cell determinations in persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections. MMWR Recomm Rep 1994; 43(RR-3):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin MJ, Gershon AA, Weinberg A, Song LY, Fentin T, Nowak B. Administration of live varicella vaccine to HIV-infected children with current or past significant depression of CD4(+) T cells. J Infect Dis 2006; 194:247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armenian SH, Han JY, Dunaway TM, Church JA. Safety and immunogenicity of live varicella virus vaccine in children with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006; 25:368–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekker V, Westerlaken GH, Scherpbier H et al. Varicella vaccination in HIV-1-infected children after immune reconstitution. AIDS 2006; 20:2321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taweesith W, Puthanakit T, Kowitdamrong E et al. The immunogenicity and safety of live attenuated varicella-zoster virus vaccine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:320–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son M, Shapiro ED, LaRussa P et al. Effectiveness of varicella vaccine in children infected with HIV. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:1806–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000; 314:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole SR, Napravnik S, Mugavero MJ, Lau B, Eron JJ Jr, Saag MS. Copy-years viremia as a measure of cumulative human immunodeficiency virus viral burden. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 171:198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brogly S, Williams P, Seage GR III, Oleske JM, Van Dyke R, McIntosh K. Antiretroviral treatment in pediatric HIV infection in the United States: from clinical trials to clinical practice. JAMA 2005; 293:2213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behrman A, Lopez AS, Chaves SS, Watson BM, Schmid DS. Varicella immunity in vaccinated healthcare workers. J Clin Virol 2013; 57:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds MA, Kruszon-Moran D, Jumaan A, Schmid DS, McQuillan GM. Varicella seroprevalence in the U.S.: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. Public Health Rep 2010; 125:860–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuter B, Matthews H, Shinefield H et al. Ten year follow-up of healthy children who received one or two injections of varicella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004; 23:132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Dyke RB, Patel K, Siberry GK et al. Antiretroviral treatment of US children with perinatally acquired HIV infection: temporal changes in therapy between 1991 and 2009 and predictors of immunologic and virologic outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 57:165–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutcliffe CG, Moss WJ. Do children infected with HIV receiving HAART need to be revaccinated? Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:630–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le T, Wright EJ, Smith DM et al. Enhanced CD4+ T-cell recovery with earlier HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:218–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pensieroso S, Cagigi A, Palma P et al. Timing of HAART defines the integrity of memory B cells and the longevity of humoral responses in HIV-1 vertically-infected children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:7939–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cagigi A, Rinaldi S, Cotugno N et al. Early highly active antiretroviral therapy enhances B-cell longevity: a 5 year follow up. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:e126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotugno N, Douagi I, Rossi P, Palma P. Suboptimal immune reconstitution in vertically HIV infected children: a view on how HIV replication and timing of HAART initiation can impact on T and B-cell compartment. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; doi:10.1155/2012/805151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gershon AA, Gershon MD. Pathogenesis and current approaches to control of varicella-zoster virus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26:728–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gershon AA, Mervish N, LaRussa P et al. Varicella-zoster virus infection in children with underlying human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis 1997; 176:1496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duncan CJ, Hambleton S. Varicella zoster virus immunity: a primer. J Infect 2015; 71(suppl 1):S47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2010; 342:341–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.