Abstract

Ectopic presence of teeth within the dentate region is common in clinical practice. However, the presence of teeth in non-dentate areas such as the nasal cavity or the maxillary sinus is rare. These may remain asymptomatic for years, may be misdiagnosed as foreign bodies, or may present with some serious complications involving the nose and paranasal sinuses. Complications such as nasal obstruction, epistaxis, headaches, rhinolith formation, epiphora, sinusitis and oro-antral fistula have been well described in literature, however, very few cases of antro-cutaneous fistulas have been reported. We discuss three cases of ectopic eruptions of teeth, all occurring in children. The clinical and radiographic findings of the cases, possible etiology, complication, diagnosis and treatment are discussed.

Keywords: Ectopic eruption, Supernumerary tooth, Nasal tooth, Maxillary sinus tooth, Antro-cutaneous fistula

Introduction

A tooth in the nasal cavity or the maxillary sinus is an unusual phenomenon. It may be symptomatic or asymptomatic and is usually misdiagnosed as a foreign body in the nasal cavity. Intranasal tooth is a rare form of supernumerary or ectopic tooth. The incidence of supernumerary teeth in the general population is 0.1–1.0 % and of these cases only a small percentage develop in the nose. Although these are rare, they must be considered in the differential diagnosis of persistent symptoms such as unilateral nasal obstruction, unilateral facial swelling, recurrent cheek abscesses, epiphora, sensory loss over the skin of the cheek or unilateral cheek fistulas. Presence of a tooth in the maxillary sinus with antro-cutaneous fistula is an even rarer presentation. We report here, three cases of teeth growing in non dentate locations, all presenting in children, and discuss their varied clinical presentations and management.

Case Series

Case 1

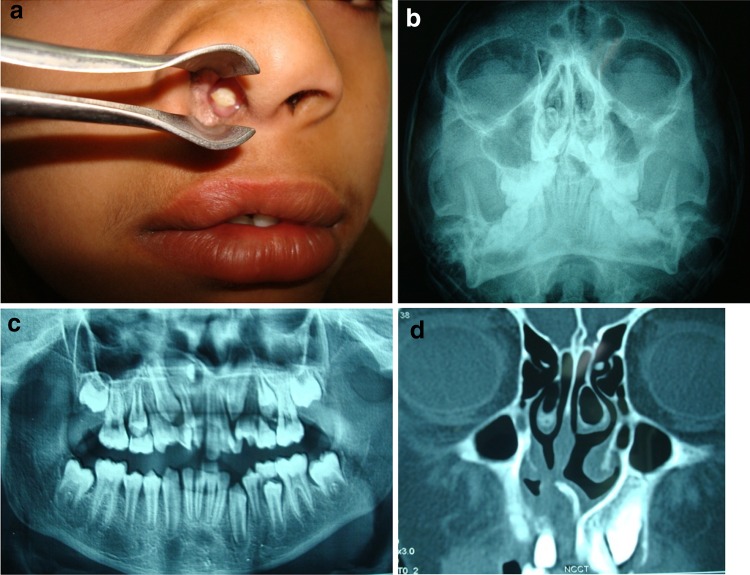

A 12 year old boy presented to the Otolaryngology Clinic accompanied by his mother. She had noticed a whitish mass in the right nasal cavity for the last 5 months. The child had been asymptomatic with no history of pain, nasal discharge, nasal obstruction or epistaxis. She had thought it to be a foreign body in the nose. However, persistence of the mass for 5 months aroused concern and she brought the child to the hospital. On examination, a scar over the upper lip suggested a previous surgery for cleft lip and palate that the child had undergone at the age of 1 year. Anterior rhinoscopy revealed a whitish structure in the floor of the nasal cavity, very close to the inferior turbinate, approximately 15 mm deep from the nostril margin. It was bony hard on palpation with granulation tissue around its embedded portion (Fig. 1a). The nasal septum was deviated towards the same side. Dental examination revealed a complete dental formula according to his age, although the teeth were mal-aligned (Fig. 2a). X-ray paranasal sinuses showed a radiopaque mass resembling a tooth in the right nasal cavity (Fig. 1b). Panoramic radiography revealed a tooth with a crown lying horizontally in the right nasal floor (Fig. 1c) and CT scan confirmed the same (Fig. 1d). A diagnosis of supernumerary intranasal tooth was made and the patient was taken up for extraction under general anaesthesia.

Fig. 1.

a Clinical photograph showing tooth like whitish structure in the nasal cavity. b X-ray paranasal sinuses showing radio-opaque mass in the right nasal cavity. c Panoramic radiograph showing tooth lying horizontally in the right nasal floor just above the central incisors. d Non contrast CT scan (Case 1) showing well defined hyper dense structure abutting the hard palate and projecting into the right nasal cavity

Fig. 2.

Mass appeared as a tooth with a crown and root

The tooth was dislocated from its site of impaction and extracted. The removed tooth was an abnormal complete tooth including radix, cervix and crown. It was approximately 12 mm in length and was white-coloured. Cervix and most of the radix of the extracted tooth were covered with mucosa or granulation tissue (Fig. 2). No residual fistula was seen within the hard palate or the floor of the nasal cavity. The patient was discharged the following day and the postoperative period remained uneventful.

Case 2

A 12 year old boy presented with right sided nasal obstruction, occasional foul smelling blood stained nasal discharge with fullness and headache for the last 3 years. Examination of the right nasal cavity showed granulations and excessive crusting in the floor of the cavity. Dental examination revealed absence of the right upper lateral incisor tooth (Fig. 2b). With suspicion of a forgotten foreign body or ectopic tooth, an NCCT paranasal sinuses was done which revealed the presence of a tooth like structure in the floor of the right nasal cavity and associated right maxillary sinusitis. The ectopic tooth was planned for extraction under general anaesthesia. After removal of granulation tissue and crusting, the tooth was found to be lying loosely in a horizontal position, between the inferior turbinate and the floor of the nasal cavity and was extracted easily under endoscopic guidance. No fistula was seen in the floor of the nasal cavity after removal of the tooth. Maxillary antrostomy was also done to clear the retained secretions in the maxillary sinus. The extracted tooth was pale yellowish in appearance, with a hollow cavity and was about 10 mm in length.

Case 3

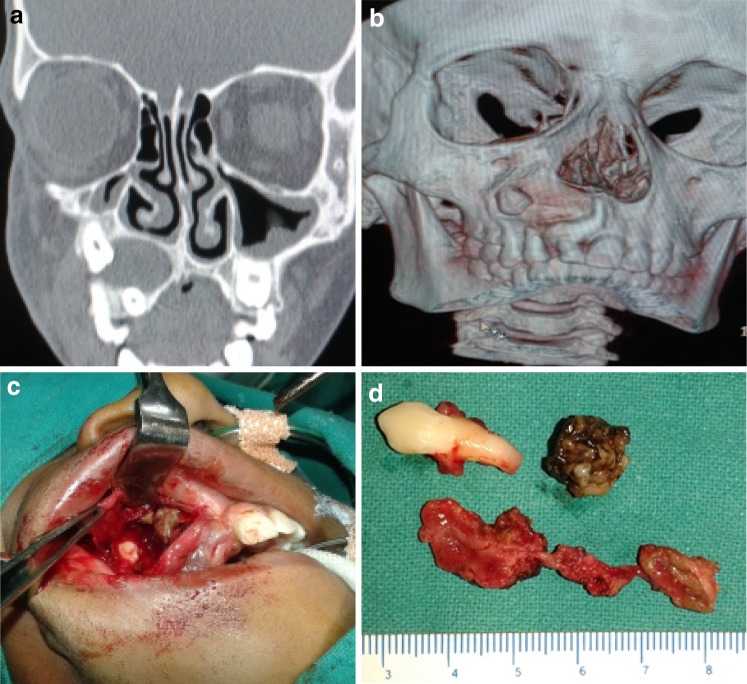

A 12 year old boy presented with right sided facial swelling with presence of a fistula over the cheek for the last 6 months (Fig. 3c). He also gave history of trauma to this region about 1 year back. On clinical examination, there was fullness of the right cheek with pain and swelling around the fistulous tract. The opening of the tract was surrounded by granulation tissue. On pressing the cheek, yellowish serous fluid was expressed. No egg shell crackling of the maxillary bone could be appreciated. The right maxillary central incisor tooth was loose and discoloured and the lateral incisor tooth was missing (Fig. 3d). Tests for cutaneous tuberculosis and histopathology of granulations from the fistulous tract were done prior to presenting at our institute. A non-contrast CT scan of the paranasal sinuses revealed a well defined expansile lytic cystic lesion in the right half of the maxillary sinus, having crown of an impacted tooth (Fig. 4a, b). Also noted, cortical breach at the lateral aspect of the lesion with thickening of skin and soft tissues with bulky buccinators muscle. A Caldwell–Luc approach was selected. A sublabial incision was made, preserving 2 mm of mucosa on the gingival side. Dissection was done in the subperiosteal plane up to the infraorbital bundle. Erosion was seen in the anterolateral wall of the maxillary sinus. The sinus cavity was filled with dirty yellowish proteinaceous deposits and straw coloured serous fluid. An ectopic tooth was seen in the supero-lateral aspect of the sinus cavity (Fig. 4c). A fistulous tract was found from the antero-lateral wall reaching up to the skin of the cheek. The tract was completely excised (Fig. 4d) and the sinus opening obliterated with muscle. The cheek skin was sutured. The patient did well postoperatively and there was no recurrence up to 2 years of follow up.

Fig. 3.

Dental examination of the patient Case 1 (a) showing normal dentition but mal-aligned teeth and Case 2 (b) showing absent right upper lateral incisor tooth, (c) Case 3 showing fistula of the right cheek with swelling, and (d) absent right upper lateral incisor

Fig. 4.

a NCCT PNS showing ectopic tooth in maxillary sinus with breach in anterolateral wall. b 3D reconstruction of the same image. c Caldwell–Luc approach showing ectopic tooth and greyish debri within the sinus. d Excised tooth, debri and fistulous tract

Discussion

The incidence of supernumerary teeth ranges from 0.1 to 1 % in the general population. However, in the Indian subcontinent, the incidence has been reported to be 2.5 % [1]. A tooth existing in the nasal cavity or maxillary sinus is a rare form of supernumerary tooth. These teeth usually have an abnormal appearance and may be single or paired, erupted or impacted and may lie in vertical, horizontal, or inverted positions.

Supernumerary teeth are more commonly related to the upper jaw and lie either in relation to the central incisors (mesiodens) or less frequently to the third molars. Other supernumerary teeth seen with the same frequency are maxillary paramolars, mandibular premolars and maxillary lateral incisors. It is interesting to note that approximately 90 % supernumerary teeth occur in maxilla and more commonly in permanent dentition. Supernumerary teeth in the deciduous dentition are much less common and when they do occur they are usually maxillary lateral incisors.

Atypical locations of supernumerary teeth include the maxillary sinus, mandibular condyle, coronoid process, orbit, palate and nasal cavity. Although, these teeth are asymptomatic, they may prevent and delay the eruption of normal teeth and lead to their malalignment in the later life. It is therefore important to identify and remove them before they cause complications.

The aetiology of supernumerary teeth is not completely understood. One theory suggests that the supernumerary tooth is created either from a thin tooth bud that arises from the dental lamina near the permanent tooth bud or the tooth germ undergoes dichotomy [2]. Another theory is that their development is a reversion to the dentition of the extinct primates, which had three pairs of incisors. The hyperactivity theory suggests that supernumerary teeth are formed as a result of local, independent, hyperactivity of the dental lamina [3]. The role of epithelial mesenchymal interaction has also been suggested [4]. Genetic factors are known to play a role as supernumeraries are more common in the relatives of affected children than in the general population without following a distinct Mendelian pattern. Also, any obstruction at the time of tooth eruption due to a crowded dentition, persistent deciduous teeth or exceptionally dense bone, developmental disturbances, such as a cleft palate, rhinogenic or odontogenic infection and displacement as a result of trauma or cysts [5] can also lead to the formation of supernumerary teeth. Rege et al. described osteomyelitis of the maxilla as a cause of nasal teeth and reported three ectopic nasal teeth, following osteomyelitis of the maxilla [6].

The symptoms caused by the ectopic tooth include unilateral nasal obstruction, foul smelling rhinorrhea, crusting, localized ulceration, nasal congestion, epistaxis and foreign body sensation. Kohli and Verma [7] reported a nasal ectopic tooth in association with a septal abscess. Other complications that can be associated with ectopic teeth include rhinitis caseosa [8], nasolacrimal duct obstruction [9], septal perforation and oro-nasal fistula [10].

Ectopic maxillary teeth may present with sinusitis, headache, cheek swelling, epiphora or oroantral fistula. Presentation in the form of antro-cutaneous fistula is extremely rare and only very few cases have been reported in literature [11].

Sometimes, it is these complications with which the patient presents, and the tooth is discovered accidentally.

Cleidocranial dysplasia and Gardner’s syndrome [12] are conditions with which the otolaryngologist should be familiar as they manifest with multiple supernumerary teeth. While there is no significant sex distribution in primary supernumerary teeth, males are affected approximately twice as frequently as females in the permanent dentition [13]. The differential diagnosis includes rhinolith, fungal infections with calcification, or benign lesions like osteomas, enchondromas, dermoids and malignant tumours like osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma especially when they are embedded in granulation tissue.

It is interesting to note that in our first case, the patient had undergone cleft lip and palate repair at the age of 1 year. Due to lack of development of a complete dentition by that age, it would have been impossible to identify the presence of a tooth bud in the nasal cavity at the time of surgery. Also the presence of a cleft in the hard palate would have further impeded the development of a normal tooth in that position. Dental formula was however complete at the time of presentation and all the teeth were present, though they were mal-aligned. Moreover, since the child was mentally retarded and the tooth was asymptomatic, it was disregarded and ignored for many months before the child was brought to the hospital.

The second case presented with nasal obstruction and blood stained nasal discharge. It was the absence of the upper lateral incisor that led to the suspicion of an ectopic tooth.

Our third case presented with cheek swelling and fistula. In such a case, a clinician is easily misled into thinking about infections of the salivary glands, underlying osteomyelitis of the maxilla/mandible, and tuberculosis of the skin of the cheek. It is important to keep in mind, the presence of an ectopic tooth of the maxillary sinus with infection and erosion of the sinus wall leading to such a condition.

An X-ray of the paranasal sinuses shows the appearance of the ectopic teeth as radio-opaque lesions with attenuation similar to that of the oral teeth. An orthopantogram may be more useful in outlining the exact relationship and orientation of the supernumerary/ectopic tooth with the existing dentition. A non contrast computed tomographic scan may be necessary to know the position and impaction of the tooth in the surrounding tissues or bone, if it is surrounded by granulations, especially in cases of cleft palate to avoid creating a defect or fistula in a previously repaired palate.

Surgery remains the treatment of choice for ectopic teeth in the nasal cavity in order to avoid potential morbidity and prevent complications. In case the patient is in the mixed dentition period, it is better to wait until the permanent teeth have erupted to avoid injury to the tooth roots, unless he presents with complications. Periodic radiographic examination and vigilance for potential complications is advised if the tooth is not to be extracted. It is usually not difficult to free the tooth from the surrounding granulation tissue and remove it from the anterior nares under local or general anaesthesia. Sometimes, the tooth may have a bony socket in the nasal floor and may become difficult to extract with bleeding obscuring the whole process [14].

In case the tooth is too big to pass through the anterior nares it can be pushed back and removed through the posterior choana. The endoscopic surgical approach used in this case caused less morbidity compared to the conventional methods related to removal of ectopic tooth. Caldwell–Luc is the best approach for maxillary ectopic teeth presenting with complications. In case the tooth is lying near the maxillary sinus ostium, it may be removed endoscopically.

References

- 1.Pradhan AC. Supernumerary tooth in palate. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1979;51:91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farmer ED, Lawten FE. Anomalies in number size and form of the teeth. In: Farmer ED, Lawton FE, editors. Stone’s oral and dental diseases. 5. Liverpool: E & S Livingstone Ltd; 1966. pp. 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu JF. Characteristics of premaxillary supernumerary teeth: a survey of 112 cases. ASDC J Dent Child. 1995;62:262–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray B, Singh LK, Das CJ, Roy TS. Ectopic supernumerary tooth on the inferior nasal concha. Clin Anat. 2006;19:68–74. doi: 10.1002/ca.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreano EH, Zich DK, Goree JC, et al. Nasal tooth. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:124–126. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rege SR, Shal KL, Marfati PT. Osteomyelitis of maxilla with extrusion of teeth in the floor of the nose requiring extraction. J Laryngol Otol. 1970;84:533–535. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100072194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohli GS, Verma PL. Ectopic supernumerary tooth in the nasal cavity. J Laryngol Otol. 1970;84:537–538. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abercrombie PH. Eruption of a canine tooth into the nasal fossa attended by rhinitis caseosa. J Laryngol Otol. 1925;40:586–589. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100027870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexandrakis G, Hubbel RN, Aitken PA. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction secondary to ectopic teeth. Opthalmology. 2000;107:189–192. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Sayed Y. Sino-nasal teeth. J Otolaryngol. 1995;24:180–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal PN. An extensive dentigerous cyst with antro-cutaneous fistula. J Laryngol Otol. 1966;40(5):544–547. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100065634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. Development of disturbances of oral and para oral structures. In: Shafer WG, editor. A text book of oral pathology. 4. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1983. pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinirons MJ. Unerupted premaxillary supernumerary teeth. A study of their occurrence in males and females. Br Dent J. 1982;153:110. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wurtele P, Dufour G. Radiology case of the month: a tooth in the nose. J Otolaryngol. 1994;23(1):67–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]