Abstract

Background

Plasmodium falciparum malaria is a significant public health problem in Comoros, and artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) remains the first choice for treating acute uncomplicated P. falciparum. The emergence and spread of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum in Southeast Asia, associated with mutations in K13-propeller gene, poses a potential threat to ACT efficacy. Detection of mutations in the P. falciparum K13-propeller gene may provide the first-hand information on changes in parasite susceptibility to artemisinin. The objective of this study is to determinate the prevalence of mutant K13-propeller gene among the P. falciparum isolates collected from Grande Comore Island, Union of Comoros, where ACT has been in use since 2004.

Methods

A total of 207 P. falciparum clinical isolates were collected from the island during March 2006 and October 2007 (n = 118) and March 2013 and December 2014 (n = 89). All isolates were analysed for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and haplotypes in the K13-propeller gene using nested PCR and DNA sequencing.

Results

Only three 2006–2007 samples carried SNPs in the K13-propeller gene, one having a synonymous (G538G) and the other having two non-synonymous (S477Y and D584E) substitutions leading to two mutated haplotypes (2.2 %, 2/95). Three synonymous mutations (R471R, Y500Y, and G538G) (5.9 %, 5/85) and 7 non-synonymous substitutions (21.2 %, 18/85) with nine mutated haplotypes (18.8 %, 16/85) were found in isolates from 2013 to 2014. However, none of the polymorphisms associated with artemisinin-resistance in Southeast Asia was detected from any of the parasites examined.

Conclusion

This study showed increased K13-propeller gene diversity among P. falciparum populations on the Island over the course of 8 years (2006–2014). Nevertheless, none of the polymorphisms known to be associated with artemisinin resistance in Asia was detected in the parasite populations examined. Our data suggest that P. falciparum populations in Grande Comore are still effectively susceptible to artemisinin. Our results provide insights into P. falciparum populations regarding mutations in the gene associated with artemisinin resistance and will be useful for developing and updating anti-malarial guidance in Comoros.

Keywords: Comoros, Plasmodium falciparum, Artemisinin resistance, K13-propeller, Polymorphism

Background

Malaria remains one of the major public health problems throughout the world, with the occurrence of estimated 225 million clinical cases and ~600,000 deaths annually [1]. In the Union of Comoros, Plasmodium falciparum malaria is the most widespread species of human malaria parasites, and was responsible for 15 % ~ 20 % of the registered deaths historically [2]. Over the past six decades, chloroquine (CQ) had been used to cure and/or to prevent malaria in Comoros [3]. Nevertheless, the increasing emergence and spread of CQ-resistant P. falciparum led to the use of the combination sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) as first-line treatment for acute uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in Comoros [3, 4]. Unfortunately, malaria control in Comoros had been imperiled by the emergence and spread of CQ- and SP-resistant P. falciparum in the early 1980s and of DDT-resistant Anopheles mosquitoes [5, 6]. In 2004, more than 100,000 malaria cases were reported in Comoros, with high level incidence (~35 %) [1]. Based on these observations, the government of Comoros introduced artemisinin combination therapy (ACT, artemether-lumefantrine) as first-line therapy for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria, and officially withdrew the use of CQ and SP in 2004 [4, 5]. Unfortunately, the ACT regime did not lead to decrease of malaria incidence, with approximately 100,000 annual malaria cases recorded from 2006 to 2012. Thus, malaria still represents one of the major public health challenges in Comoros, being responsible for ~38 % out-patient consultations and ~60 % of all hospitalizations. A countrywide malaria control and elimination policy was launched by the government of Comoros in 2006, with the goal to basically control malaria by 2015 and to completely eliminate malaria by 2020. To block malaria transmission in this endemic area, mass drug administration with therapeutical dose of artemisinin-piperaquine and low-dose of primaquine (Artepharm Co. Ltd, PR China) was launched by late 2013 on Grande Comore Island. The effort has accelerated with impetus from the Global Fund in 2012, in which large-scale distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets has also been gradually implemented on Grande Comore, Moheli, and Anjouan Islands, Union of Comoros [4], hoping to reach up to 89.1 and 46.3 % of the households with at least 1 mosquito net and 1 insecticide-impregnated mosquito net, respectively. Consequently, the annual malaria cases dramatically changed from 114,537 in 2007 to 2142 in 2014 (a 98.0 % reduction). To achieve the goal of malaria elimination, there is an urgent need to monitor parasite susceptibility to artemisinin, and to develop and update anti-malarial guidance in Comoros.

ACT has been implemented world-wide as the first-line treatment for acute uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria since 2001, and has been responsible for the reduction in malaria-associated mortality and morbidity [7, 8]. Currently, artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum parasites have been reported mostly in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Laos [9–15]. Previous experience with the spread of CQ- and SP-resistant parasites from Asia to Africa suggests that the spread of artemisinin resistance to other parts of the world is likely, and that vigilant surveillance for artemisinin resistant parasites is important for controlling the spread of resistance [16–18]. Therapeutic efficacy studies under field conditions, considered the gold standard for determining anti-malarial drug efficacy, is currently complicated primarily due to limited numbers of malaria individuals available in low malaria transmission areas [19]. Therefore, molecular genetic markers of resistance are also useful for monitoring the emergence and spread of anti-malarial drug resistance [20, 21]. Mutations and variations in expression of several genes such as pfmdr1 and pfatpase6 have been suggested, but not proven, to be the molecular marker of artemisinin resistance [22–24]. Recent studies have shown that artemisinin resistance is associated with non-synonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a P. falciparum gene with kelch propeller domain (K13-propeller, PF3D7_1343700) in Southeast Asia [12, 13, 25, 26]. Specifically, three mutations (C580Y, R539T and Y493H) in the K13-propeller gene were strongly associated with increased ring stage survival and delayed parasite clearance [12]. Meanwhile, artemisinin tolerance in vitro was associated with the M476I mutation of K13-propeller [12].

As resistance to earlier anti-malarial drugs (CQ and SP) spread from Asia to Africa and other parts of world through parasite migration, there is a serious concern that a similar scenario may occur with artemisinin resistance [16–18]. Recently, it was reported that highly artemisinin-resistant parasites could also emerge independently in Southeast Asia, indicating that K13-propeller gene polymorphisms have multiple origins throughout Africa as well as Southeast Asia [26]. Comoros is a malaria-endemic country with a history of ACT (artemether-lumefantrine) use since 2004, and a mass drug administration (MDA) of artemisinin-piperaquine plus low-dose of primaquine was launched for blocking malaria transmission on Grande Comore Island in 2013. Under such continuous and widespread artemisinin selective pressure, it can be expected that a similar phenomenon seen in Southeast Asia may occur in Comoros. Currently, no molecular epidemiologic information on P. falciparum parasite populations on Grande Comore Island in response to artemisinin is avaialable. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the frequencies and patterns of mutations in K13-propeller gene linked to artemisinin resistance of Grande Comore P. falciparum clinical isolates. Our data will provide important information for molecular surveillance of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum in this area.

Methods

Ethical statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of Comoros Ministry of Health (protocol No. 12521/MSSPG/CAB) and Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (protocol No. 2012L0816). A written informed consent form was read and signed by all participants before any study procedure was performed. The individuals who could not read and write in the language, signed the form with their thumb print after it was completed by an independent witness on their behalf.

Study sites

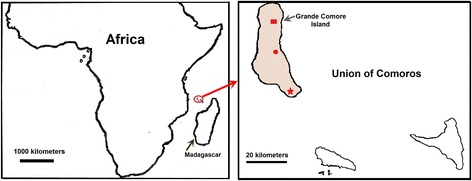

The study was conducted on Grande Comore Island, Union of Comoros (latitude 11°00′-12°00′S; longitude 43°10′-43°35′E), in the Indian Ocean between Madagascar and the eastern coast of Africa (Fig. 1). This island has an area of 1147 km2 with a human population around 420,000 in 2012. The climate of this island is characterized by a warm, wet summer, and a cool, dry winter. The area has a distinct seasonal climate characterized by rainy season (November-April) and dry season (May-October), with temperature ranging from 11 to 35 °C and rainfall ranging from 1000 to 3000 mm annually. This island was a highly endemic area for P. falciparum and P. malariae malaria, with P. falciparum being the most common species (>95.5 %) [27]. Malaria transmission is perennial, with a peak during the rainy season throughout this island. Four confirmed Anopheles species (Anopheles gambiae, An. funestus, An. merus, and An. coustani) are present on this island, with An. gambiae being the predominant vector [27].

Fig. 1.

Map of Grande Comore Island, Union of Comoros. Shown are the locations of Mitsoudje Center Hospital (□), National Malaria Center (○), and Mitsamiouli Center Hospital (☆) where P. falciparum isolates were collected

Study samples

Blood samples were collected from patients with symptomatic P. falciparum malaria admitted to Mitsoudje Center Hospital, National Malaria Center, and Mitsamiouli Center Hospital for anti-malarial drug treatment (Fig. 1). After informed consent from all adults or legal guardians of children, thick and thin blood smears were prepared and were stained with 10 % Giemsa to diagnose human malaria species. Patients infected with P. falciparum only (no other human malaria species) as confirmed by peripheral smear examination were included in this study. One study was conducted between March 2006 and October 2007, and the other between March 2013 and December 2014. From each individual, a 1.0 ml of whole blood sample was collected in an EDTA tube and stored at −20 °C until DNA extraction. A total of 207 P. falciparum clinical isolates were collected on Grande Comore Island in one period March 2006 and October 2007 (n = 118), and in another period March 2013 and December 2014 (n = 89).

Extraction of parasite DNA

Genomic DNA was extracted from 100 μL of each whole blood sample using DNA blood kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Takara, Japan). The extracted DNA was eluted in 60 μL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 0.1 M EDTA, pH 8.0) and stored at −20 °C until use. The quality of genomic DNA was detected using 1.0 % agarose gel electrophoresis and goldviewer buffer staining used as ethidium bromide substitute (Sangon Bio Inc., Shanghai, China).

PCR amplification and sequencing of P. falciparum K13-propeller

To amplify the P. falciparum K13-propeller, a nested PCR amplification method was used following previously reported protocols [12]. Oligonucleotide primers and cycling conditions are listed in Table 1. The total 25 μl amplification reaction mixtures contained 8.5 ~ 10.0 μl of dH2O, 1.0 μl of each primer (10 pM), and 12.5 μl of Taq PCR Master Mix following the manufacturer’s instructions (Sangon Bio Inc., Shanghai, China). Primary amplification reactions were initiated with the addition of 2.0 μL of template genomic DNA prepared from the blood samples. For the nested PCR, 0.5 μL of primary PCR productions was used as template. The amplified PCR products were detected on 2 % agarose gel, and the sizes of the PCR products were measured visually based on a 100 bp DNA ladder (Sangon Bio Inc., Shanghai, China). The nested PCR products of K13-propeller were directly sequenced in both directions, using an ABI PRISM3730 DNA sequencer (Sangon Bio Inc., Shanghai, China). The nucleotide and amino acid sequences of K13-propeller were compared with wild-type amino acid sequence (GenBank accession number, XM_001350122) using Clustal W of the BioEdit 7.0 and MEGA 4.0 programs.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and cycling conditions used to amplify K13-propeller gene of Plasmodium falciparum isolates a

| Genesb | Primersc | PCR cycling conditions | Product size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K13-propeller (P) | F: 5′-cggagtgaccaaatctggga-3′ R: 5′-gggaatctggtggtaacagc-3′ |

95 °C 5 min/[95 °C 30 s, 60 °C 90 s, 72 °C 90 s] × 40 cycles, 72 °C 10 min | 2096 | [12] |

| K13-propeller (S) | F: 5′-gccaagctgccattcatttg-3′ R: 5′-gccttgttgaaagaagcaga-3′ |

95 °C 5 min/[95 °C 30 s, 60 °C 90 s, 72 °C 90 s] × 40 cycles, 72 °C 10 min | 848 | [12] |

a P. falciparum isolates from Grande Comore Island, Union of Comoros

b P Primary PCR reaction, S Secondary PCR reaction

c F Forward primer, R Reverse primer

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined with SPSS software (version 13.0). Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare in the prevalence of the mutations and alleles of parasite samples between two collected periods. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

All blood samples (n = 207) were collected from P. falciparum mono-species infections identified after microscopy examination of blood smears. Because of low parasitemia and/or poor DNA quality, we were not able to successfully amplify the P. falciparum K13-propeller gene from all the samples; only 87.0 % of the P. falciparum isolates from Grande Comore Island (n = 180) could be amplified, including samples collected during 2006–2007 (n = 95) and 2013–2014 (n = 85). Sequencing of the gene revealed only one synonymous mutation at codons G538G (GGT → GGA) among the isolates from 2006 to 2007 group (1.1 % of the isolates examined, 1/95) (Table 2). Three synonymous substitutions, R471R (CGT → CGC), Y500Y (TAT → TAC), and G538G (GGT → GGA) were found in isolates from 2013 to 2014 (5.9 % of the isolates examined, 5/85). Interestingly, G538G substitution was detected in isolates from both groups. Meanwhile, non-synonymous mutations at codons S477Y and D584E, with the frequencies of 2.2 % (2/95), were detected in isolates from 2006 to 2007. In contrast, more than 20 % (18/85) of the isolates from 2013 to 2014 carried seven non-synonymous mutations (D464H, D464Y, S477Y, L488S, A504T, I526M, A578S, and D584E) in the K13-propeller domain, including two mutations (S477Y and A578S) that have been reported previously in Africa (Kenya and Uganda). Of these mutations, the most prevalent change was D464H/Y (5.9 %, 5/85), followed by A578S (4.7 %, 4/85) and D584E (3.5 %, 3/85). The number of non-synonymous mutations increased significantly from 2.2 % (in 2006–2007) to 21.2 % (in 2013–2014) (P < 0.05) in Grande Comore isolates. However, none of the C580Y, R539T, or Y493H mutations previously associated with delayed parasite clearance in Southeast Asia isolates, or the M476I substitution selected in vitro in a Tanzanian strain, was observed in these parasite populations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of K13-propeller mutations in Plasmodium falciparum isolatesa

| Areas | Mutations | Amino acid and genetic changesb | Number of isolates (%)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2007 (n = 95) | 2013–2014 (n = 85) | |||

| Mitsoudje Center Hospital | Synonymous | R471R (CGT → CGC) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) |

| G538G (GGT → GGA) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | ||

| Non-synonymous | D464H (GAT → CAT) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| D464Y (GAT → TAT) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| L488S (TTG → TCG) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| I526M (ATA → ATG) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| A578S (GCT → TCT) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | ||

| D584E (GAT → GAA) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| National Malaria Center | Synonymous | Y500Y (TAT → TAC) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Non-synonymous | D464H (GAT → CAT) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| S477Y (TCT → TAT) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| I526M (ATA → ATG) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| A578S (GCT → TCT) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | ||

| Mitsamiouli Center Hospital | Synonymous | Y500Y (TAT → TAC) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Non-synonymous | D464Y (GAT → TAT) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | |

| S477Y (TCT → TAT) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| A504T (GCT → ACT) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| D584E (GAT → GAA) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | ||

aIsolates collected from 2006 to 2007 and 2013 to 2014 along Grande Comore Island of Comoros

bThe mutated amino acids and nucleotides are indicated in bold type

cStatistically significant differences for comparison with isolates circulating in 2006–2007 from Grande Comore Island (*P < 0.05) using Mann–Whitney U test

Haplotype analysis of P. falciparum K13-propeller gene in isolates from 2006 to 2007 revealed only three distinct allelic forms (Table 3), including the wild-type allele, and two single-mutant alleles (477Y and 584E). Of the three allelic variants, the most prevalent allelic variant was wild-type allele (97.9 %, 93/97). Ten allelic variants [wild-type allele, seven single-mutant alleles (464H, 464Y, 477Y, 488S, 526M, 578S, and 584E), and two double-mutant alleles (477Y/504T and 526M/578S)] were detected in 85 isolates from 2013 to 2014, with wild-type allele being predominant (81.2 %, 69/85). The remaining allelic variants were evenly distributed at low frequency (1.2 to 3.5 %) among isolates from 2013 to 2014. It should be noted that all three haplotypes [(wild-type allele, and two single-mutant alleles (477Y and 584E)] detected in 2006–2007 isolates were also found in 2013–2014. Over the course of 8 years (2006–2014), the wild-type allele prevalence significantly decreased from 97.9 to 81.2 % (P < 0.05), and the mutant alleles prevalence significantly increased from 2.1 to 18.8 % (P < 0.05) in Grande Comore isolates. However, no significant differences in each measured mutated allelic forms were found between 2006–2007 and 2013–2014 groups (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Prevalence of single nucleotide polymorphisms and multi-mutated haplotypes in Plasmodium falciparum K13-propeller genea

| Areas | Genotypes | Number of isolates (%)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2007 (n = 95) | 2013–2014 (n = 85) | ||

| Mitsoudje Center Hospital | Wild-type haplotype D464S477L488A504I526A578D584 | 30 (31.6) | 20 (23.5)* |

| Single-mutant haplotype H 464S477L488A504I526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype Y 464S477L488A504I526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464S477 S 488A504I526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464S477L488A504I526 S 578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464S477L488A504I526A578 E 584 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Double-mutant haplotype D464S477L488A504 M 526 S 578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| National Malaria Center | Wild-type haplotype D464S477L488A504I526A578D584 | 45 (47.4) | 33 (38.9)* |

| Single-mutant haplotype H 464S477L488A504I526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464 Y 477L488A504I526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464S477L488A504 M 526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464S477L488A504I526 S 578D584 | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Mitsamiouli Center Hospital | Wild-type haplotype D464S477L488A504I526A578D584 | 18 (18.9) | 16 (18.8) |

| Single-mutant haplotype Y 464S477L488A504I526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464 Y 477L488A504I526A578D584 | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Single-mutant haplotype D464S477L488A504I526A578 E 584 | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Double-mutant haplotype D464 Y 477L488 T 504I526A578D584 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | |

Note: The double mutants were confirmed in repeated amplification and sequencing experiments

aIn isolates collected from 2006 to 2007 and 2013 to 2014 along Grande Comore Island, Union of Comoros. The mutated amino acids are indicated by bold type

bStatistically significant differences for comparison with isolates circulating in 2006–2007 from Grande Comore Island (*P < 0.05) using Mann–Whitney U test

Discussions

In Comoros, ACT has been introduced as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria since 2004 [4, 5]. Although ACT remains highly efficacious for the treatment of falciparum malaria, and delayed parasite clearance of ACT has not been noted in Comoros [28], it is important to monitor the potential presence of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum populations because the emergence and spread of artemisinin-resistant strains in Southeast Asia-an epicenter of resistance to several other anti-malarial drugs (CQ and SP) [9–15, 29]. Clinical artemisinin resistance is defined as a reduced parasite clearance rate, expressed as an increased parasite clearance half-life or a persistence of microscopically detectable parasites on the third day of ACT. The half-life parameter correlates strongly with results from the in vitro ring-stage survival assay (RSA0–3 h) and results from the ex vivo RSA. Unfortunately, due to poor field conditions (frequent power outage and the lack of liquid N2 storage and in vitro parasite culture), we were not able to culture P. falciparum parasites collected from Grande Comore Island for RSA0–3 assay. At present, we are not sure whether the point mutations in K13-propeller gene can serve as molecular markers for detecting potential artemisinin resistance and for monitoring malaria-control measures in Comoros. This study investigated the prevalence of mutant SNPs in K13-propeller gene of Grande Comore P. falciparum isolates collected from two different periods (2006–2007 and 2013–2014). Our data indicated that the frequencies of non-synonymous mutations in K13-propeller significantly increased in isolates from 2013 to 2014 when compared with those from 2006 to 2007. However, none of the mutations (C580Y, R539T, Y493H, and M476I) previously associated with artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia parasites [12, 13, 25, 26] was observed in the parasite populations collected from both examined periods, suggesting that P. falciparum populations in Grande Comore are still effectively susceptible to artemisinin.

Our data were in line with other reports describing K13-propeller polymorphisms in P. falciparum collected from Africa, in which 24 non-synonymous mutations were detected at low frequencies, and most of them were different from the mutations observed in Southeast Asia when more than 2600 samples were analyzed from 15 countries [30–32]; Meanwhile, with the exception of 1 case in Nigeria and 2 cases in Congo, there were no reported cases of delayed parasite clearance or of prolonged RSA0–3 hours in sub-Saharan Africa to date [13, 33]. These observations suggest that not all K13-propeller mutations are associated with artemisinin resistance, and that secondary loci are involved in resistance Asian parasites, but not in African parasites. Additionally, high levels of antimalarial immunity can mask a resistance phenotype [34]. Unlike in Southeast Asia, individuals in malaria-endemic regions of sub-Saharan Africa are less likely to be infected with clonal parasites because of the high transmission intensity and are thus likely to lose potential resistance-conferring alleles to outcrossing. It is known that the subpopulations of parasites can be categorized as artemisinin-susceptible or -resistant, based on their genetic profile [35]. Therefore, the different polymorphisms in K13-propeller gene observed between Southeast Asia and Africa may be due to different genetic backgrounds. Whether the K13-propeller SNPs we observe here can be used as molecular markers for artemisinin resistance globally requires further investigations considering various parameters such as malaria parasite ancestry, geographical, clinical, epidemiological, and genetic diversities [31].

This study identified three synonymous mutations (R471R, Y500Y, and G538G) in K13-propeller in 3.3 % (6/180) of examined isolates. Of these mutations, mutation at codon G538G was detected in both examined periods (2006–2007 and 2013–2014) with the similarly low frequency (less than 3 %), indicating that the emergence of parasites with synonymous mutation at codon G538G should not attribute to artemisinin selective pressure on Grande Comore Island. In the present study, two synonymous mutations (Y500Y and G538G) were reported from parasite population in Kenya [36]. Similarly, R471R synonymous mutation found in this study was observed in Congo [30], Gabon [31], and Angola [37]. Although these synonymous mutations should not affect K13-propeller protein structure and function and likely plays no role in artemisinin resistance, the paucity of shared synonymous mutation between Comoros’ and African parasites suggesting that there exists a large reservoir of K13-propeller polymorphisms globally.

It has been suggested that Y493H, I543T, R539T, and C580Y mutations in K13-propeller gene are associated with prolonged parasite survival ex vivo; Y493H, R539T, and C580Y mutations are linked to in vivo delayed parasite clearance; and M476I mutation is related to artemisinin tolerance in vitro [12, 13, 25, 26]. In the present study, only two mutations at codons S477Y (1.1 %) and D584E (1.1 %) and two mutated-allelic types were detected in isolates from 2006 to 2007, suggesting that P. falciparum isolates collected in 2006–2007 showed very limited variability within the K13-propeller gene. In contrast, mutations at positions 464 (5.9 %), 477 (2.4 %), 488 (1.2 %), 504 (1.2 %), 526 (2.4 %), 578 (4.7 %), and 584 (3.5 %) leading to nine mutated allelic types (18.8 %) in K13-propeller gene were detected in isolates from 2013 to 2014. Our data was similar to those in other reports, where three of the 18 imported malaria isolates (16.7 %) from the Grande Comore showed polymorphism (N490H, N554K and E596G), and double-mutant haplotype occurred at very low frequencies [38]. The data in the current study showed that a trend of increase in the number of polymorphismic sites in P. falciparum K13-propeller gene is presented in Grande Comore isolates through the years of sample collection, may be due to the selective artemisinin pressure continually from the long history of ACT use since 2004. However, mutations strongly associated with artemisinin resistance (C580Y, R539T, Y493H, and M476I) in Southeast Asia parasites were not observed in isolates from both examined periods in the present study. Our observation is consistent with those in previous reports from Kenya [36], Angola [37], Mozambique [37], Senegal [39], Ugandan [40] as well as other areas of Sub-Saharan Africa [30], Caribbean’s Haiti [41], and South Asia’ Bangladesh [42], where the K13-propeller gene mutations associated with artemisinin resistance were absent. Additionally, trials of ACT for treating uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in Uganda [43], Kenya [44], and Mozambique [45] have found 28-day PCR-corrected cure rates of 89 % or greater. Thus, our data is strongly suggesting that many Grande Comore P. falciparum isolates collected in 2013–2014 are likely still sensitive to artemisinin even under the drug selective pressure from introduction of ACT as the first-line treatment since 2004. Additionally, our results also suggest that selective artemisinin drug pressure may exist in Grande Comore Island that promotes these mutations, but not substantially enough to lead clinical drug resistance. Whether or not the non-synonymous substitutions in K13-propeller gene observed in our study are associated with artemisinin drug response, can not be inferred from our results. However, these mutations in K13-propeller gene observed in our study may provide some background mutations setting the stage for emergence of artemisinin resistance. Studies of careful comparison of parasites with these allelic types and their response to artemisinin are necessary to determine whether these mutations contribute artemisinin resistance.

Recently, it was reported that highly artemisinin-resistant parasites could have emerged independently in Southeast Asia [26]. In the present study, seven non-synonymous mutations were detected among the 180 Grande Comore isolates. Of these mutations, five occurred at positions 464, 488, 504, 526, and 584. These mutations present new mutations that have not been previously reported in other endemic areas, suggesting that independent emergence of the same mutations may occur on Grande Comore Island. Notably, the S477Y mutation detected in the present study was comparable to those reported in other areas of the world, such as Kenya [36]. Similarly, the A578S mutation detected in Grande Comore Island isolates was concordance with previous reports in Kenya [36], Uganda [30, 40], South Asia’ Bangladesh [42] and Cambodia [12]. Therefore, our data suggested that these mutations in K13-propeller gene of P. falciparum populations have a global distribution. But it remains an open question as to whether the presence of A578S mutation in these samples was due to independent emergence or had spread from other areas. Protein modeling data suggest that A578S can alter the function of the K13 propeller protein because it lies adjacent to the C580Y mutation that can cause delayed parasite clearance in Cambodia [42]. Nevertheless, the artemisinin collaboration group also found the A578S mutation in one specimen within their study areas but this mutation was not associated with increased parasite clearance half-life [12]. In addition, other mutation (V566I) is also located close to the C580Y mutation [12, 31]; however, whether V566I mutation has the same ability to alter the function of K13 protein required further investigation. Due to the presence of many different mutations among parasites from various endemic regions, further studies are required to validate the effect of the mutations.

Conclusion

Results from the current study showed that the number of mutations in the P. falciparum K13-propeller gene has significantly increased in Grande Comore isolates from 2006 to 2014. However, none of the mutations (C580Y, R539T, Y493H, or M476I) previously associated to artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia parasites was observed in parasite populations collected from the Grande Comore Island (2006–2007 and 2013–2014). Although we were not able to collect data related to the in vivo or in vitro efficacy of ACT on parasites in this study, the results suggest that P. falciparum populations on Grande Comore Island are still susceptible to artemisinin, even under widespread drug selective pressure from the introduction of ACT as the first-line treatment for over 10 years. Careful monitoring of parasite populations on changes in the K13-propeller gene and genes known to play a role in resistant to other antimalarial drugs are necessary.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cindy Clark of the NIH Library for editing. This work was supported in part by grants from Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81273643] and International S&T Cooperation Program of China [grant numbers 2009DFA31180] to JS, China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [grant number 2015M570699] and Guangdong Provincial Science Foundation [grant number 2015A030310107] to BH, Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81403295] to CD, Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou [2014J4500037] to YG, and by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (X-zS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Bo Huang and Changsheng Deng contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JS and BH designed, organized, and supervised the program, and analyzed the data. BH, CD, TY, LX, AB, KA, RA, and AM carried out the field work. BH and X-zS analyzed data, wrote and revised the manuscript. QW, SH, YL, SZ, YG, QX, JZ, JY, YZ, and FL participated in fieldwork and preliminary data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Bo Huang, Email: huangbo198421@126.com.

Changsheng Deng, Email: dcs19811202@hotmail.com.

Tao Yang, Email: 942966792@qq.com.

Linlu Xue, Email: 1121595778@qq.com.

Qi Wang, Email: wangqi198169@163.com.

Shiguang Huang, Email: thshg@126.com.

Xin-zhuan Su, Email: xsu@niaid.nih.gov.

Yajun Liu, Email: liuyajun9808@126.com.

Shaoqin Zheng, Email: graceguangzhou@qq.com.

Yezhi Guan, Email: gyz111@hotmail.com.

Qin Xu, Email: xuqin@163.com.

Jiuyao Zhou, Email: 68722514@qq.com.

Jie Yuan, Email: 466754442@qq.com.

Afane Bacar, Email: anfanebacar@yahoo.fr.

Kamal Said Abdallah, Email: kamalsaid2004@yahoo.fr.

Rachad Attoumane, Email: rachadkeke@yahoo.fr.

Ahamada M. S. A. Mliva, Email: amsamliva@yahoo.com

Yanchun Zhong, Email: 447373997@qq.com.

Fangli Lu, Email: 489589715@qq.com.

Jianping Song, Email: songjpgz@sina.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Malaria Report 2013. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ouledi A. Epidemiology and control of malaria in the Federal Islamic Republic of Comoros. Sante. 1995;5:368–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randrianarivelojosia M, Raherinjafy RH, Migliani R, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Ariey F, Bedja SA. Plasmodium falciparum resistant to chloroquine and to pyrimethamine in Comoros. Parasite. 2004;11:419–23. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2004114419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebaudet S, Bogreau H, Silaï R, Lepère J, Bertaux L, Pradines B, et al. Genetic structure of Plasmodium falciparum and elimination of malaria, Comoros archipelago. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1686–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silai R, Moussa M, Abdalli M, Astafieva-Djaza M, Hafidhou M, Oumadi A, et al. Surveillance of falciparum malaria susceptibility to antimalarial drugs and policy change in the Comoros. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2007;100:6–9. doi: 10.3185/pathexo2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tall A, Rabarijaona L, Robert V, Bedja S, Ariey F, Randrianarivelojosia M. Efficacy of artesunate plus amodiaquine, artesunate plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, and chloroquine plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum in the Comoros Union. Acta Trop. 2007;102:176–81. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashley EA, White NJ. Artemisinin-based combinations. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:531–6. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000186848.46417.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosman A, Mendis KN. A major transition in malaria treatment: the adoption and deployment of artemisinin-based combination therapies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Status report on artemisinin resistance: September 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2619–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:411–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phyo A, Nkhoma S, Stepniewska K, Ashley EA, Nair S, McGready R, et al. Emergence of artemisinin-resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2012;379:1960–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60484-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thriemer K, Hong NV, Rosanas-Urgell A, Phuc BQ, Ha do M, Pockele E, et al. Delayed parasite clearance after treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in Plasmodium falciparum malaria patients in central Vietnam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:7049–55. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02746-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su XZ. Tracing the geographic origins of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108:261–2. doi: 10.1179/2047772414Z.000000000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joy D, Feng X, Mu J, Furuya T, Chotivanich K, Krettli AU, et al. Early origin and recent expansion of Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 2003;300:318–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1081449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wootton J, Feng X, Ferdig MT, Cooper RA, Mu J, Baruch DI, et al. Genetic diversity and chloroquine selective sweeps in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;418:320–3. doi: 10.1038/nature00813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . Methods and techniques for clinical trials on antimalarial drug efficacy: genotyping to identify parasite populations. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . Global report on antimalarial drug efficacy and drug resistance: 2000–2010. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mu J, Duan J, Makova KD, Joy DA, Huynh CQ, Branch OH, et al. Chromosome-wide SNPs reveal an ancient origin for Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;418:323–6. doi: 10.1038/nature00836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alker AP, Lim P, Sem R, Shah NK, Yi P, Bouth DM, et al. Pfmdr1 and in vivo resistance to artesunate-mefloquine in falciparum malaria on the Cambodian-Thai border. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:641–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jambou R, Legrand E, Niang M, Khim N, Lim P, Volney B, et al. Resistance of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates to in vitro artemether and point mutations of the SERCA-type PfATPase6. Lancet. 2005;366:1960–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui L, Wang Z, Jiang H, Parker D, Wang H, Su XZ. Lack of association of the S769N mutation in Plasmodium falciparum SERCA (PfATP6) with resistance to artemisinins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2546–52. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05943-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straimer J, Gnädig NF, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Duru V, Ramadani AP, et al. Drug resistance. K13-propeller mutations confer artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. Science. 2015;347:428–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1260867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takala-Harrison S, Jacob CG, Arze C, Cummings MP, Silva JC, Dondorp AM, et al. Independent emergence of artemisinin resistance mutations among Plasmodium falciparum in Southeast Asia. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:670–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li G, Song J, Deng C, Moussa M, Ahamada M, Fatihou O, et al. One-year report on the fast elimination of malaria by source eradication (FEMSE) project in Moheli Island of Comoros. Journal of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2010;27:90–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng C, Song J, Tan B, Mariata R, Ali S, Abobacar S, et al. Clinical trial of artequick-primaquine for the treatment of 155 falciparum malaria patients in Comoros. Journal of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2012;29:197–201. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tun K, Imwong M, Lwin KM, Win AA, Hlaing TM, Hlaing T, et al. Spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Myanmar: a cross-sectional survey of the K13 molecular marker. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(4):415–21. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70032-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor S, Parobek C, DeConti D, Kayentao K, Coulibaly S, Greenwood B, et al. Absence of putative artemisinin resistance mutations among Plasmodium falciparum in Sub-Saharan Africa: a molecular epidemiologic study. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:680–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamau E, Campino S, Amenga-Etego L, Drury E, Ishengoma D, Johnson K, et al. K13-propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1352–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maïga-Ascofaré O, May J. Is the A578S single nucleotide polymorphism in K13-propeller a marker of emerging resistance to artemisinin among Plasmodium falciparum in Africa? J Infect Dis. 2015; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Maiga AW, Fofana B, Sagara I, Dembele D, Dara A, Traore OB, et al. No evidence of delayed parasite clearance after oral artesunate treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:23–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takala-Harrison S, Laufer M. Antimalarial drug resistance in Africa: key lessons for the future. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1342:62–7. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miotto O, Almagro-Garcia J, Manske M, Macinnis B, Campino S, Rockett K, et al. Multiple populations of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Cambodia. Nat Genet. 2013;13:648–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isozumi R, Uemura H, Kimata I, YIchinose Y, Logedi J, Omar A, et al. Novel mutations in K13 propeller gene of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:490–2. doi: 10.3201/eid2103.140898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escobar C, Pateira S, Lobo E, Lobo L, Teodosio R, Dias F, et al. Polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum K13-Propeller in Angola and Mozambique after the Introduction of the ACTs. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torrentino-Madamet M, Collet L, Lepère J, Benoit N, Amalvict R, Ménard D, et al. K13-propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from patients in Mayotte in 2013 and 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:7878–81. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01251-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torrentino-Madamet M, Fall B, Benoit N, Camara C, Amalvict R, Fall M, et al. Limited polymorphisms in k13 gene in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Dakar, Senegal in 2012–2013. Malar J. 2014;13:472. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conrad M, Bigira V, Kapisi J, Muhindo M, Kamya M, Havlir D, et al. Polymorphisms in K13 and Falcipain-2 associated with artemisinin resistance are not prevalent in Plasmodium falciparum isolated from Ugandan children. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carter T, Boulter A, Existe A, Romain J, Victor J, Mulligan C, et al. Artemisinin resistance-associated polymorphisms at the K13-propeller locus are absent in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Haiti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:552–4. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohon A, Alam M, Bayih A, Folefoc A, Shahinas D, Haque R, et al. Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum K13 propeller gene from Bangladesh (2009–2013) Malar J. 2014;13:431. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorsey G, Staedke S, Clark TD, Njama-Meya D, Nzarubara B, Maiteki-Sebuguzi C, et al. Combination therapy for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Ugandan children: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2210–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.20.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thwing JI, Odero CO, Odhiambo FO, Otieno KO, Kariuki S, Ord R, et al. In vivo efficacy of amodiaquine-artesunate in children with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria inwestern Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nhama A, Bassat Q, Enosse S, Nhacolo A, Mutemba R, Carvalho E, et al. In vivo efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children: a multisite, open-label, two-cohort, clinical trial in Mozambique. Malar J. 2014;13:309. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]