Abstract

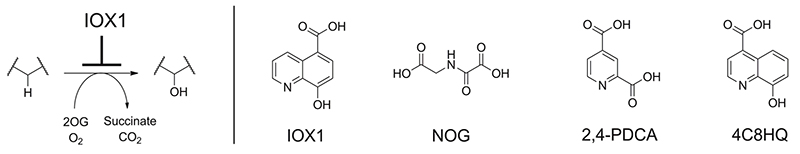

2-Oxoglutarate and iron dependent oxygenases are therapeutic targets for human diseases. Using a representative 2OG oxygenase panel, we compare the inhibitory activities of 5-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (IOX1) and 4-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (4C8HQ) with that of two other commonly used 2OG oxygenase inhibitors, N-oxalylglycine (NOG) and 2,4-pyridinedicarboxylic acid (2,4-PDCA). The results reveal that IOX1 has a broad spectrum of activity, as demonstrated by the inhibition of transcription factor hydroxylases, representatives of all 2OG dependent histone demethylase subfamilies, nucleic acid demethylases and γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase. Cellular assays show that, unlike NOG and 2,4-PDCA, IOX1 is active against both cytosolic and nuclear 2OG oxygenases without ester derivatisation. Unexpectedly, crystallographic studies on these oxygenases demonstrate that IOX1, but not 4C8HQ, can cause translocation of the active site metal, revealing a rare example of protein ligand-induced metal movement

Introduction

2-Oxoglutarate (2OG) dependent oxygenases are an enzyme superfamily that catalyses a large set of biologically important oxidations. In humans, 2OG oxygenases catalyse hydroxylation and demethylation reactions on multiple substrates including nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, and small molecules. Catalysis by 2OG oxygenases utilises a ferrous ion, molecular oxygen and 2-oxoglutarate (2OG), which react to form a reactive Fe(IV)-oxo intermediate that subsequently oxidises their substrates.1-4 2OG oxygenases are therapeutic targets for diseases including anaemia, ischemia-related disorders, and cancer.5, 6 Most current 2OG oxygenase inhibitors are 2OG competitors, including N-oxalylglycine (NOG) and 2,4-pyridinedicarboxylic acid (2,4-PDCA).7-11 Both NOG and 2,4-PDCA have been widely used as 2OG oxygenase inhibitors; however there are no reports of their activity against multiple 2OG oxygenases using a common assay platform.12 Further, for biological work they need to be used in ester ‘pro-drug’ forms in order to enable cell-penetration - the requirement for diester hydrolysis introduces an undesired variable.13, 14 Other 2OG mimetic compounds have shown selective inhibition against particular sets of 2OG oxygenases, although in many cases, ester forms are also required for efficient cell penetration.

From a therapeutic perspective it is unclear to what extent the inhibition of individual 2OG oxygenases (isoforms) is required. For example in the case of the hypoxic response, the extent to which the activities of separate hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) hydroxylases contribute to the physiologically observed hypoxia phenotypes is unclear and is likely context dependent. Further, in cases where multiple oxygenases act on the same substrate (or substrate type), as is the case for the JmjC histone demethylases, comprehensive inhibition of all such oxygenases can be beneficial for research purposes, and potentially could also be so in some clinical contexts. There is thus interest in developing broad spectrum inhibitors either acting on all human 2OG oxygenases or on particular sets of them. This might be achieved by use of iron-chelators, or by use of competing metals (e.g. Co(II), which has been used to treat anaemia, presumably acting, at least in part, via 2OG oxygenase inhibition); however such treatments will likely affect other proteins. An alternative strategy is to use conformationally constrained 2OG analogues that are accommodated in the conserved, but non-identical, 2OG binding pockets.

Here we describe comparative inhibition and biophysical studies on 5-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (IOX1), NOG and 2,4-PDCA with multiple human 2OG oxygenases. IOX1 was identified as a 2OG oxygenase inhibitor in vitro (KDM4E (JMJD2E)) using a high-throughput screen for the histone demethylases.15 Our results reveal that IOX1 is a broad spectrum inhibitor in both in vitro assays, and in cells against both cytosolic and nuclear oxygenases. Unexpectedly, in some cases IOX1 binding induces translocations of the active site iron, opening the way for novel inhibitor development.

Results and Discussion

In vitro profiling of IOX1 and generic inhibitors of 2OG oxygenases

To investigate the inhibition profiles for NOG, 2,4-PDCA and IOX1, we determined their IC50 values against a panel of 2OG oxygenases using a largely unified assay platform.12 In this study, we expanded our reported enzyme panel to 14 active 2OG oxygenases including hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) hydroxylases (prolyl hydroxylase domain isoform 2 (PHD2), factor inhibiting HIF (FIH)), 10 JmjC-domain containing histone lysine demethylases (KDM2A, PHF8, KDM3A, KDM4A-E, KDM5C and KDM6A/B), a nucleic acid demethylase (AlkB from E. coli) and γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase (BBOX1). 2OG concentrations were maintained at or near the experimentally determined apparent KM values for 2OG (KMapp) to enable comparisons (Table 1). As a consequence of crystallographic studies (see below), we also analysed 8-hydroxy-4-carboxylic acid (4C8HQ), a structural isomer of IOX1. All four of the tested compounds inhibit all of the 2OG oxygenases in the panel (except NOG against PHF8, Table 1). For those where IC50 values were previously reported, their potencies were generally found to be in the similar range. Previous studies have shown that NOG and 2,4-PDCA inhibit other 2OG oxygenases including collagen hydroxylases.7 The results indicate that the degree of inhibition varies substantially across the 2OG oxgyenase panel (Tables 1 and S1). Analysis of rank order of potencies (Table S1) indicates IOX1 and 2,4-PDCA display the broadest spectrum of inhibition (mean rank potencies of 1.78 and 2.14 respectively), followed by 4C8HQ (2.57), then NOG (2.85). Notably, NOG is the most potent of the four compounds against the HIF prolyl hydroxylase (PHD2) and shows comparable potency (at least in some assays) against HIF asparaginyl hydroxylase (FIH), validating its use as a hypoxia mimetic. IOX1 was the most potent inhibitor against 8 of the 10 tested KDMs. IOX1 exhibited IC50 values at 1 μM or lower against the KDM3, KDM4 and KDM6 subfamilies, and 5-25 μM against the KDM5 and KDM2/7 subfamilies. IOX1 was the least potent compound against BBOX1 (IC50 196 μM); however, this value is only slightly above those for the other inhibitors (IC50s 82-124 μM, note the high 2OG KMapp for BBOX1 of 160 μM, Table 1).

Table 1. IC50 and Ki values for N-oxalylglycine (NOG), 2,4-pyridinedicarboxylic acid (2,4-PDCA), 5-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (IOX1), and 4-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (4C8HQ) against 2OG Oxygenases.

IC50 determinations were performed using AlphaScreen assays except where the values are in brackets, where an MS-based assay was used, underlined where a formaldehyde dehydrogenase based assay was used, or in italics where 2OG (14C-labelled) consumption assay was used. Experimental details are in the Supporting Information. IC50 values against γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase (BBOX) were determined using either a fluoride ion detection based assay (FA) or using an NMR based assay (NMR).22

| 2OG oxygenase | Catalytic function (substrate) | KMapp 2OG ((μM) | IC50 (μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOX1 | NOG | 2,4-PDCA | 4C8HQ | |||

| PHD2 | Prolyl-hydroxylase (HIF1α) | 116, 60 17 * | (14.3)15,14.3 | (0.8)18, Ki = 817, 1019 | (6)15, Ki = 717*, 28.6 | 41 |

| FIH | Asparaginyl-hydroxylase (HIF1α) | 1020, 2516 | (20.5)15, (7.6) | (46)18, Ki = 221, (< 1) | (1.1)15, Ki = 3021, (<1) | (7.5) |

| KDM4A (JMJD2A) | KDM (H3K9/K36Me3,Me2) | 6 18 | 0.2, (1.7)15 | 17 18 | (0.4)15, 1.95 | 1.4 |

| KDM4C (JMJD2C) | KDM (H3K9/K36Me3,Me2) | 4 18 | 0.6 | 14 18 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| KDM4D (JMJD2D) | KDM (H3K9Me3,Me2) | 6.9 | 0.2 | 34 | 1.1 | 7.3 |

| KDM4E (JMJD2E) | KDM (H3K9Me3,Me2) | 13.2 22 | 0.3 (2.4)15 | 90-250 | 1-6 (1.4)15 | 3 |

| KDM3A (JMJD1A) | KDM (H3K9Me2,Me1) | 5.3 12 | 0.17 | 2 | 8 | 15 |

| KDM6B (JMJD3) | KDM (H3K27Me3,Me2,Me1) | 5.4 12 | 0.14 | 0.3 | 33 | 9 |

| KDM6A (UTX) | KDM (H3K27Me3,Me2,Me1) | 14.7 | 1.1 | 13 | 67 | 3.7 |

| KDM2A (FBXL11) | KDM (H3K36Me2,Me1) | 12.5 12 | 15.4 | 45,25218 | 4.1 | 18.2 |

| PHF8 | KDM (H3K36Me2; H4K20Me1) | 16.6 12 | 15, (12.6) | (>300) | (153) | (17) |

| KDM5C (JARID1C) | KDM (H3K4Me3,Me2,Me1) | 41.7 12 | 25 | 7.5, (9) | 0.45 (0.9) | 27 |

| BBOX1 | 3 S-hydroxylation (γ-butyrobetaine) | 160 (NMR)23, 470 (FA)23 | 196 (FA) | 124 (NMR)23, 390 (FA)23 | 82 (FA)23 | 111 (FA) |

| AlkB | E.coli DNA/RNA-repair (1meA/3meC) | 11.4 † | 10.2 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 10.2 |

indicates values attained using PHD2 protein purified from cell extracts.

KMapp value attained using recombinant full-length AlkB. KDM = histone Nε-methyllysine demethylase. A schematic representation of oxygenase catalysis is shown on the left. The scheme shows the stoichiometry of 2OG oxygenase catalysis; in the case of the JmjC KDM enzymes, fragmentation of the hydroxylated product occurs to enable demethylation.

IOX1 chelates to Fe(II) in the active site of 2OG oxygenases

To investigate the inhibition modes of IOX1 for different 2OG oxygenases, X-ray crystal structures of IOX1 in complex with FIH (PDB IDs: 3OD4 and 4BIO), KDM6B (PDB ID: 2XXZ) and AlkB (PDB ID: 4JHT) were solved to 2.2, 1.8 and 1.2 Å resolution, respectively (Figures 1 and 2). Together with the reported structure of KDM4A in complex with IOX1 (PDB ID: 3NJY),13 the new structures enable comparison of the IOX1 binding modes in the active sites of multiple 2OG oxygenases and also enable comparison of IOX1 binding relative to reported structures with NOG and 2,4-PDCA.2, 24 Overall, IOX1 binding mimics both the metal chelation and carboxylate interactions involved in 2OG binding, consistent with solution studies suggesting IOX1 inhibition is likely derived, at least in part, by competition for active site binding with 2OG.15

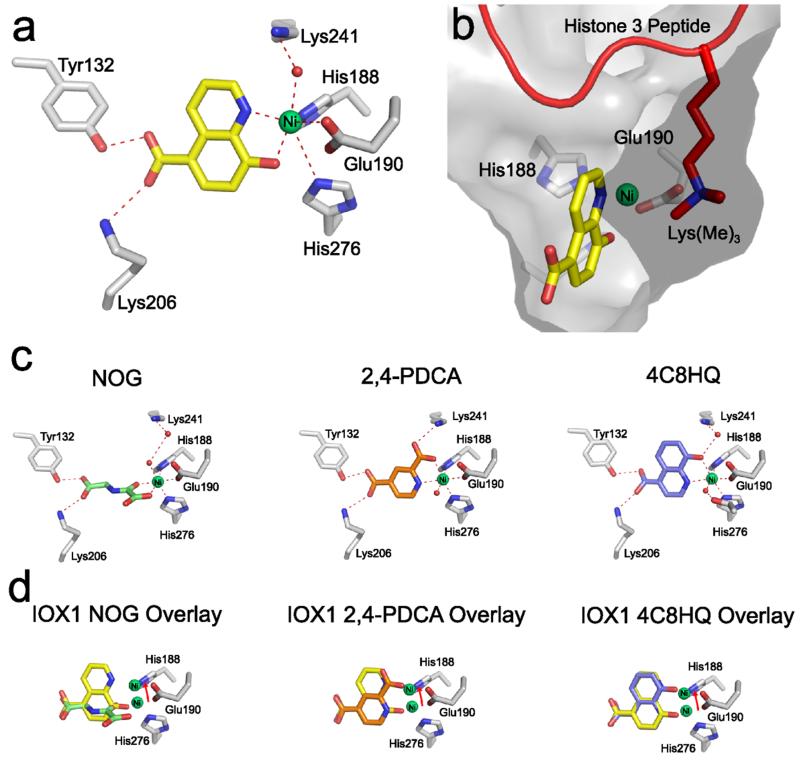

Figure 1. Views from crystal structures of NOG, 2,4-PDCA, 4-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (4C8HQ) and IOX1 bound to KDM4A.

(a) Views from crystal structures of KDM4A bound to IOX1 (yellow, PDB ID: 3NJY).13 IOX1 induces translocation of the active site metal. (b) View from a crystal structure of IOX1 (yellow) bound to KDM4A overlaid with histone 3 peptide fragment trimethylated at lysine-9 (from PDB ID: 2OQ6).25 The protein is shown as a surface. The metal position is as in the IOX1 structure (see (a)). (c) Views from crystal structures of NOG (green, left, PDB ID: 2OQ6),25 2,4-PDCA (orange, middle, PDB ID: 2VD7) and 4C8HQ (blue, right, PDB ID: 4BIS) bound to KDM4A. No translocation of the active site metal is observed in any of these structures. (d) Views from crystal structures of NOG (green, left), 2,4-PDCA (orange, middle) and 4C8HQ (blue, right) bound to KDM4A, overlaid with the IOX1 structure. Translocation of the active site metal is highlighted (arrows).

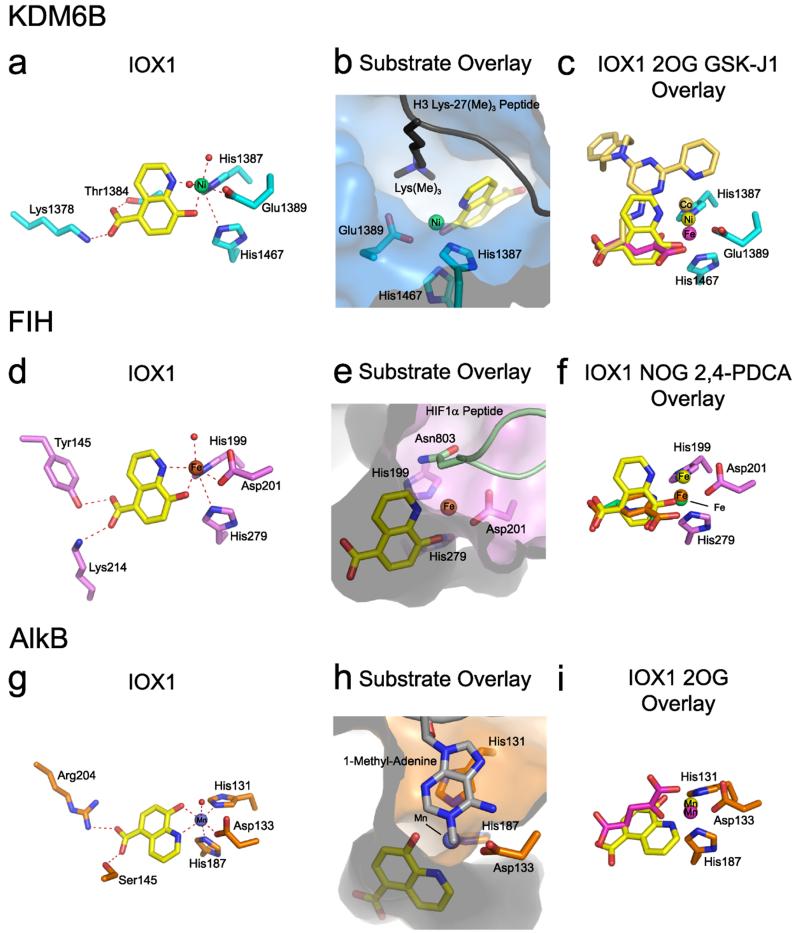

Figure 2. Views from crystal structures of IOX1 bound to KDM6B, FIH and AlkB.

(a) View from a structure of KDM6B bound to IOX1 (yellow, PDB ID: 2XXZ). IOX1 induces translocation of the active site metal relative to its position with 2OG/2,4-PDCA. (b) View from a structure of IOX1 (yellow) bound to KDM6B overlaid with a histone H3 peptide fragment trimethylated at lysine-27 (from PDB ID: 4EZH).26 The protein is shown as a surface. The metal position is as in the IOX1 structure (see (a)). (c) Overlays from structures of 2OG (magenta, PDB ID: 2XUE),26 GSK-J1 (gold, PDB ID: 4ASK)26 and IOX1 (yellow) bound to KDM6B. The respective active site metals from the inhibitor structures (iron with 2OG, cobalt with GSK-J1, and nickel with IOX1) are shown. The metal colours are identical to the respective inhibitors. GSK-J1 induces the most significant metal translocation (cobalt). (d) View from a crystal structure of FIH bound to IOX1 (yellow, PDB ID: 4BIO). IOX1 induces translocation of the active site metal relative to its position with NOG/2,4-PDCA. (e) View from a crystal structure of IOX1 (yellow) bound to FIH overlaid with a HIF1α peptide fragment (from PDB ID: 1H2K).10 The protein is shown as a surface. The metal position is as in the IOX1 structure (see (d)). (f) Overlays from crystal structures of NOG (green, PDB ID: 1H2K),10 2,4-PDCA (orange, 2W0X)11 and IOX1 (yellow, PDB ID: 4BIO) bound to FIH. The respective active site iron atoms from the structures (bottom with NOG, middle with 2,4-PDCA, top with IOX1) are shown. The metal colours are identical to the respective inhibitors. Only IOX1 induces substantial metal translocation. (g) View from a crystal structure of AlkB bound to IOX1 (yellow, PDB ID: 4JHT). The phenolic OH group coordinates trans to the aspartate residue (Asp133) and the pyridyl nitrogen trans to the first histidine of the HXD/E…H motif (His131). (h) View from a crystal structure of IOX1 (yellow) bound to AlkB overlaid with a double-stranded DNA fragment incorporating 1-methyl-adenine (from PDB ID: 3BIE).27 The protein is shown as a surface. The metal position is as in the IOX1 structure (see (g)). (i) Overlay from crystal structures of 2OG (magenta, PDB ID: 3I3Q)28 and IOX1 (yellow) bound to AlkB. A relatively small metal translocation is observed with IOX1 (2.4 Å between His187 and manganese, relative to 2.2 Å).

In all of the structures, IOX1 is observed to chelate the active site metal (Fe or Zn for FIH, Ni for KDM4A and KDM6B, and Mn for AlkB) in a bidentate manner via its pyridinyl nitrogen and phenolic hydroxyl groups. When bound to KDM4A, KDM6B and FIH, the pyridinyl nitrogen chelates trans to the aspartate/glutamate of the conserved HXD/E…H metal binding motif (Glu190 in KDM4A, Glu1389 in KDM6B and Asp201 in FIH) with the phenolic hydroxyl chelating trans to a metal bound water. The 5-carboxylate of IOX1 is positioned to form hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions with an active site lysine residue (Lys206 in KDM4A, Lys1378 in KDM6B and Lys214 in FIH), and also forms a hydrogen bond with a tyrosine/threonine residue (Tyr132 in KDM4A, Thr1384 in KDM6B and Tyr145 in FIH). In addition, an aromatic π-π stacking interaction is apparent between the planar quinoline ring and Phe185 in KDM4A (Figure S1).

In the AlkB structure, IOX1 is also observed to bind the active site metal; however, the phenolic hydroxyl group of IOX1 chelates trans to the aspartate (Asp133) and the pyridyl nitrogen trans to the first histidine of the HXD/E…H motif (His-1, Figure 2g). The orientation of the quinoline ring is also different to the orientations observed with KDM4A, KDM6B and FIH.

This difference is likely due to steric constraints in the AlkB active site (associated with residues Asn120, Tyr122 and Leu128) which preclude binding of IOX1 in the mode observed in the other three structures (for overlay of the IOX1 structures with AlkB and KDM4A, see Figure S3). Further, in AlkB the 5-carboxylate group of IOX1 is coordinated in a slightly different geometry to that observed for 2,4-PDCA and 2OG (Figure 2g), being positioned so that only one of its carboxylate oxygens interacts with Arg204, apparently correlating with the weaker inhibition observed for AlkB by IOX1.

Comparison of the IOX1 structures with reported 2OG oxygenase structures reveals a striking difference in the relative position of the active site metal. In the structures with KDM4A, KDM6B and FIH, the active site metal is translocated relative to its positions in structures with NOG or 2,4-PDCA. In all cases, the distances between the metal and both the first histidine (His-1) and the negatively charged carboxylate oxygen of the aspartate/glutamate (O1, see Table S2) are relatively unchanged. In contrast, the inter-atomic distances between the second histidine (His-2) of the HXD/E…H motif and the metal lengthen from 2.0-2.2 Å in structures with NOG, 2,4-PDCA or 2OG, to 3.5-3.7 Å with IOX1 (Table S2 and Figure S2). Further, the inter-atomic distances between the metal and the aspartate/glutamate carbonyl oxygen which is further away from the metal (O2) decrease from 3.4-3.7 Å in structures with NOG, 2,4-PDCA or 2OG, to 2.7-3.3 Å with IOX1 (Table S2). Translocation was observed with IOX1-protein crystals formed using Fe(II), Ni(II), Zn(II) and Mn(II), demonstrating that movement is independent of the metal.

In order to investigate the structural basis of metal translocation, we synthesized the structural homologue 4-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline (4C8HQ, Table 1), and co-crystallised it with KDM4A (PDB ID: 4BIS). In this structure, 4C8HQ binds in a similar overall fashion to IOX1; however, the metal-ligand distances reveal no evidence for metal translocation (Figure 1c and Table S2). The IC50 values for 4C8HQ against KDM4A and KDM6B are 4 μM and 9 μM respectively, which are significantly higher than the corresponding IC50 values for IOX1 (0.3 μM and 0.14 μM respectively). Potential energy calculations on IOX1 and 4C8HQ complexes with KDM4A are consistent with a lower energy conformation for IOX1 over 4C8HQ (ΔE = −7.8 kcal mol−1, see Supplementary Information). These results therefore suggest that metal displacement correlates with inhibitory potency, at least for 8-hydroxyquinolines with KDM4A. This hypothesis is further supported by comparison of the IOX1 structures with a crystal structure of the potent and selective KDM6B inhibitor GSK-J126 (Figure S4, IC50 60 nM by AlphaScreen inhibition assay), which also causes translocation of the KDM6B active site metal (Figure 2).26 However, no significant variation in inhibitory potency is observed between IOX1 and 4C8HQ against FIH (IC50 values of 7.6 μM and 7.5 μM respectively, Table 1), despite FIH metal translocation by IOX1. With AlkB, IOX1 binding only results in a relatively small displacement of the active site metal (2.4 Å between His-2 of the metal binding triad and the metal, compared to ≥3.5 Å for the other IOX1 structures). This observation implies that, at least when manganese is present, substantial metal translocation by IOX1 is disfavoured for AlkB.

Cellular activity of IOX1 and pro-drugs of NOG (DMOG) and 2,4-PDCA (dmPDCA)

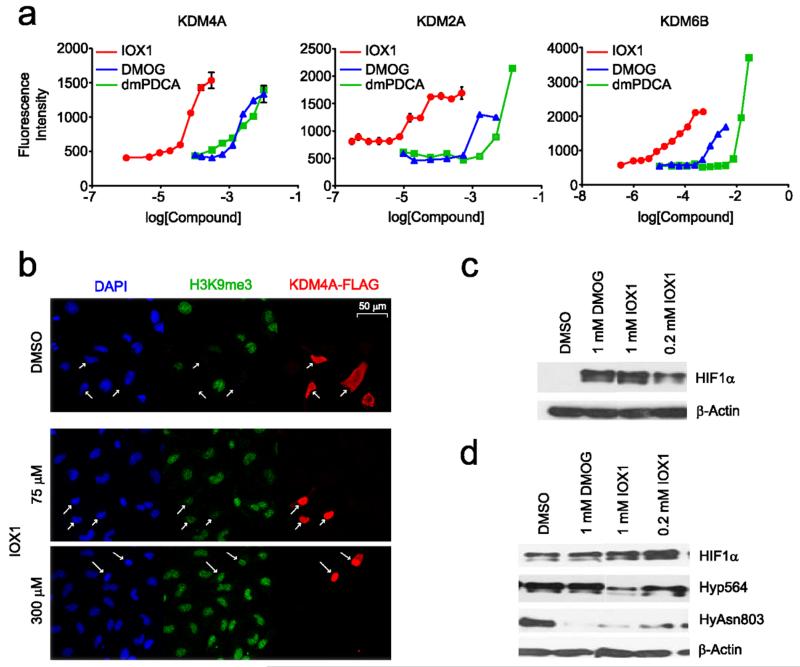

We then compared the inhibition of 2OG oxygenases in cells using the membrane-penetrating ester forms of NOG and 2,4-PDCA i.e. dimethyl-NOG (DMOG) and dimethyl-2,4-PDCA (dmPDCA), and underivatised IOX1 (Figure 3). HeLa cells transiently overexpressing KDM4A, KDM6B and KDM2A were treated with inhibitors and the changes in the global methylation levels were quantified by immunofluorescence.15 In this study, the reported immunofluorescence assay was miniaturised to a 96-well plate format and robust datasets were obtained, with good signal window (at least 2-fold) for staining with H3 lysine methylation specific antibodies. In HeLa cells overexpressing the KDMs, global hypomethylation was observed, as determined by the reduction in the levels of methyl-lysine antibody staining (relative to cells untreated with inhibitor, Figures 3b, S5 and S6).

Figure 3. IOX1 is active in cells.

(a) EC50 curves for IOX1, DMOG and dimethyl-2,4-pyridinedicarboxylate (dmPDCA) against cells overexpressing KDM4A (left), KDM2A (centre) and KDM6B (right). KDM4A EC50 values: IOX1 (86 μM), DMOG (3.5 mM), dmPDCA (3 mM), KDM2A EC50 values: IOX1 (24 μM), DMOG (1.2 mM), dmPDCA (5 mM), KDM6B EC50 values: IOX1 (37 μM), DMOG (1.2 mM), dmPDCA (~10 mM). (b) IOX1 upregulates H3K9me3 levels in HeLa cells overexpressing KDM4A. The immunofluorescence images show HeLa cells stained with DAPI nuclear stain (blue), a specific antibody against trimethylated lysine residues at H3K9 (green), and Flag-tag antibody (red), dosed once with DMSO and IOX1 at 75 μM and 300 μM concentrations. Treatment with IOX1 resulted in increased H3K9me3 levels in a dose-dependent manner, reflecting a decrease in KDM4A activity. (c) Western blot analysis shows IOX1 upregulates HIF1α in RCC4/VHL cells by a similar potency to dimethyl-N-oxalylglycine (DMOG) at 1 mM. (d) IOX1 inhibits both HIF prolyl and asparaginyl hydroxylation in RCC4 cells. DMOG was used as a positive control. Western blots were analyzed with HIF1α hydroxylation specific antibodies.29

When cells were treated with inhibitors, dose-dependent increases in global methylation were observed for HeLa cells overexpressing KDM4A, KDM6B and KDM2A (Figure 3a). For DMOG and dmPDCA, the EC50 values were in the mM range (1~10 mM) for all KDMs. Notably, IOX1 exhibited higher cellular potency than DMOG or dmPDCA, with EC50 values at 86 μM (KDM4A), 37 μM (KDM6B) and 24 μM (KDM2A). The CC50 for IOX1, DMOG and dmPDCA were >1 mM in HeLa cells (Figure S7).

We then tested IOX1 against the HIF hydroxylases in cells. RCC4/VHL cells (in which HIF1α is degraded by the ubiquitin proteasome system in a Von Hippel lindau protein (VHL) dependent manner)29 were treated with IOX1 and DMOG over 5 hours (Figure 3c). HIF1α levels were then determined by western-blotting. IOX1 was found to stabilise HIF1α, relative to the DMSO control, at a concentration of 0.2 mM. Further, western-blot analysis of hydroxylated HIF1α in RCC4 cells (in which HIF1α is stabilised due to absence of VHL)29 revealed that IOX1 treatment (5 hours) decreases hydroxylation of HIF1α Pro564 and Asn803, indicating inhibition of both HIF1α prolyl and asparingyl hydroxylation, and thus of PHD and FIH activity (Figure 3d).

Conclusions

Overall, in vitro and cell-based studies reveal that IOX1 is a broad-spectrum inhibitor of multiple biologically important and clinically relevant 2OG oxygenases. Importantly, IOX1, unlike NOG and 2,4-PDCA, inhibits both KDMs and HIF hydroxylases in cells without derivatisation. The two possible coordination modes observed for IOX1 with different subfamilies of oxygenases may help to extend its spectrum of activity. The structural analyses will also enable the rational modification of the 8-hydroxyquinoline template in order to engineer selective inhibitors. The degree of inhibition by IOX1 does vary for different 2OG oxygenases, as it does for NOG and 2,4-PDCA; thus, to achieve comprehensive inhibition in cells, it may in some circumstances be optimal to use combinations of inhibitors. The inhibitory activity of IOX1 is likely imparted by both 2OG and, in some cases, ‘prime’ substrate competition, suggesting that IOX1 may retain useful potency when either 2OG or substrate concentrations are relatively high compared to enzyme concentrations (as may occur in cells). We thus propose IOX1 as a useful broad spectrum cell active inhibitor for 2OG oxygenases.

The observation that IOX1 and GSK-J1 can cause metal movement is unprecedented in structural observations on 2OG oxygenases. Neither has such ligand-induced metal movements been commented on for other metallo-enzymes, though ligands that induce metal-binding have been reported.30, 31 Metal movement was observed with IOX1 in the cases of FIH, KDM4A and KDM6B (with IOX1 and GSK-J126). It was likely not observed with AlkB due to steric constraints (thus it could occur with AlkB with other compounds). The metal movement is independent of the metal, being observed with Fe(II), Ni(II), Zn(II) and Co(II). From an oxygenase mechanism perspective, metal movement is interesting because to date the ferrous iron has been assumed to adopt a fixed position. During catalysis, the iron plays roles that include binding the 2OG and O2 co-substrates and mediating redox transfers. There is evidence for conformational changes during catalysis and even metal-centred rearrangements.32, 33 The observation that small molecules can induce metal movement raises the possibility that such movements may occur during catalysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Michelle Daniel and the Structural Genomics Consortium biotechnology group for their support in protein production. This research was supported in part by the Wellcome Trust, the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission in the United Kingdom, the Biotechnology and Biological Research Council (U.K.), the European Research Council, Cancer Research U. K., the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence and the Royal Society. The Structural Genomics Consortium is a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, GlaxoSmithKline, Karolinska Institutet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Ontario Innovation Trust, the Ontario Ministry for Research and Innovation, Merck & Co., Inc., the Novartis Research Foundation, the Swedish Agency for Innovation Systems, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research and the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information available: Experimental details of in vitro and cell-based inhibition assays, crystallization conditions, crystallography methods, refinement statistics, computational analyses and syntheses of IOX1 and 4C8HQ.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Hausinger RP. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;39:21–68. doi: 10.1080/10409230490440541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clifton IJ, McDonough MA, Ehrismann D, Kershaw NJ, Granatino N, Schofield CJ. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:644–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flashman E, Schofield CJ. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:86–87. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0207-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walport LJ, Hopkinson RJ, Schofield CJ. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012;16:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill P, Shukla D, Tran MG, Aragones J, Cook HT, Carmeliet P, Maxwell PH. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19:39–46. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kampranis SC, Tsichlis PN. Adv. Cancer Res. 2009;102:103–169. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)02004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose NR, McDonough MA, King ON, Kawamura A, Schofield CJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4364–4397. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00203h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowdhury R, McDonough MA, Mecinovic J, Loenarz C, Flashman E, Hewitson KS, Domene C, Schofield CJ. Structure. 2009;17:981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawamura A, Tumber A, Rose NR, King ONF, Daniel M, Oppermann U, Heightman TD, Schofield CJ. Anal. Biochem. 2010;404:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elkins JM, Hewitson KS, McNeill LA, Seibel JF, Schlemminger I, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Schofield CJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:1802–1806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conejo-Garcia A, McDonough MA, Loenarz C, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, Ge W, Liénard BM, Schofield CJ, Clifton IJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:6125–6128. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose NR, Woon EC, Tumber A, Walport LJ, Chowdhury R, Li XS, King ON, Lejeune C, Ng SS, Krojer T, Chan MC, Rydzik AM, Hopkinson RJ, Che KH, Daniel M, Strain-Damerell C, Gileadi C, Kochan G, Leung IK, Dunford J, Yeoh KK, Ratcliffe PJ, Burgess-Brown N, von Delft F, Muller S, Marsden B, Brennan PE, McDonough MA, Oppermann U, Klose RJ, Schofield CJ, Kawamura A. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:6639–6643. doi: 10.1021/jm300677j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamada S, Kim TD, Suzuki T, Itoh Y, Tsumoto H, Nakagawa H, Janknecht R, Miyata N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:2852–2855. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackeen MM, Kramer HB, Chang K-H, Hopkinson RJ, Schofield CJ, Kessler BM. J. Proteome Res. 2010;9:4082–4092. doi: 10.1021/pr100269b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King ONF, Li XS, Sakurai M, Kawamura A, Rose NR, Ng SS, Quinn AM, Rai G, Mott BT, Beswick P, Klose RJ, Oppermann U, Jadhav A, Heightman TD, Maloney DJ, Schofield CJ, Simeonov A. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koivunen P, Hirsila M, Remes AM, Hassinen IE, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:4524–4532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsila M, Koivunen P, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30772–30780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chowdhury R, Yeoh KK, Tian YM, Hillringhaus L, Bagg EA, Rose NR, Leung IK, Li XS, Woon EC, Yang M, McDonough MA, King ON, Clifton IJ, Klose RJ, Claridge TD, Ratcliffe PJ, Schofield CJ, Kawamura A. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:463–469. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chowdhury R, Candela-Lena JI, Chan MC, Greenald DJ, Yeoh KK, Tian YM, McDonough MA, Tumber A, Rose NR, Conejo-Garcia A, Demetriades M, Mathavan S, Kawamura A, Lee MK, van Eeden F, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Schofield CJ. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1021/cb400088q. in press. DOI: 10.1021/cb400088q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewitson KS, McNeill LA, Riordan MV, Tian YM, Bullock AN, Welford RW, Elkins JM, Oldham NJ, Bhattacharya S, Gleadle JM, Ratcliffe PJ, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:26351–26355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koivunen P, Hirsila M, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9899–9904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakurai M, Rose NR, Schultz L, Quinn AM, Jadhav A, Ng SS, Oppermann U, Schofield CJ, Simeonov A. Mol. Biosys. 2009;6:357–364. doi: 10.1039/b912993f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rydzik A, Leung IKH, Kochan GT, Thalhammer A, Opperman U, Claridge TDW, Schofield CJ. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:1559–1563. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aik W, McDonough MA, Thalhammer A, Chowdhury R, Schofield CJ. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng SS, Kavanagh KL, McDonough MA, Butler D, Pilka ES, Lienard BMR, Bray JE, Savitsky P, Gileadi O, von Delft F, Rose NR, Offer J, Scheinost JC, Borowski T, Sundstrom M, Schofield CJ, Oppermann U. Nature. 2007;448:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature05971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruidenier L, Chung C-W, Cheng Z, Liddle J, Che K, Joberty G, Bantscheff M, Bountra C, Bridges A, Diallo H, Eberhard D, Hutchinson S, Jones E, Katso R, Leveridge M, Mander PK, Mosley J, Ramirez-Molina C, Rowland P, Schofield CJ, Sheppard RJ, Smith JE, Swales C, Tanner R, Thomas P, Tumber A, Drewes G, Oppermann U, Patel DJ, Lee K, Wilson DM. Nature. 2012;488:404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature11262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang CG, Yi C, Duguid EM, Sullivan CT, Jian X, Rice PA, He C. Nature. 2008;452:961–965. doi: 10.1038/nature06889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu B, Hunt JF. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:14315–14320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812938106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian YM, Yeoh KK, Lee MK, Eriksson T, Kessler BM, Kramer HB, Edelmann MJ, Willam C, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:13041–13051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.211110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz BA, Clark JM, Finer-Moore JS, Jenkins TE, Johnson CR, Ross MJ, Luong C, Moore WR, Stroud RM. Nature. 1998;391:608–612. doi: 10.1038/35422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janc JW, Clark JM, Warne RL, Elrod KC, Katz BA, Moore WR. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4792–4800. doi: 10.1021/bi992182j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang ZH, Ren JS, Stammers DK, Baldwin JE, Harlos K, Schofield CJ. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:127–133. doi: 10.1038/72398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung IKH, Krojer T, Kochan GT, Henry L, von Delft F, Claridge TDW, Oppermann U, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:1316–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.