Abstract

Objective. To evaluate the impact of admission characteristics on graduation in an accelerated doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program.

Methods. Selected prematriculation characteristics of students entering the graduation class years of 2009-2012 on the Worcester and Manchester campuses of MCPHS University were analyzed and compared for on-time graduation.

Results. Eighty-two percent of evaluated students (699 of 852) graduated on time. Students who were most likely to graduate on-time attended a 4-year school, previously earned a bachelor’s degree, had an overall prematriculation grade point average (GPA) greater than or equal to 3.6, and graduated in the spring just prior to matriculating to the university. Factors that reduced the likelihood of graduating on time were also identified. Work experience had a marginal impact on graduating on time.

Conclusion. Although there is no certainty in college admission decisions, prematriculation characteristics can help predict the likelihood for academic success of students in an accelerated PharmD program.

Keywords: admission, PharmD, graduation rate, accelerated

INTRODUCTION

The process of making admission decisions for pharmacy school applicants is complex and imperfect. A recent report by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy noted that a majority (75.2%) of students applying for colleges and schools of pharmacy had 3 or more years of postsecondary educational experiences.1 Many schools of pharmacy in the United States offer a 6-year doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program, which students attend following a recent graduation from high school. However, earning a bachelor’s degree allows for admission as a transfer student, bypassing all prepharmacy portions of the curriculum. Reflective of this educated pool of students, programs that offer an accelerated PharmD and accept students directly into the professional years continue to grow. The accelerated nature of the program potentially imparts unique academic demands on students that do not exist in traditionally-paced programs.

The myriad backgrounds of students choosing to attend an accelerated program include having already earned prerequisite credits at other institutions, which represent a broad spectrum of competitiveness, intellectual challenge, and ability to prepare students for the academic rigors of an accelerated program. Although many students opting to attend accelerated programs have recently graduated from other 4-year degree programs, other applicants have already built careers and then made the decision to return to school, seek a degree in pharmacy, and begin a new career.

Many studies assess factors and their impact on academic outcomes of students attending 6-year pharmacy programs, with grade point average (GPA) and scores on standardized tests such as the Pharmacy College Admission Test (PCAT) considered the best predictors,2-11 although universal conclusions are difficult to make. Other studies consider alternative outcomes of academic success such as academic probation, graduation without delay or suspension, or academic dismissal.12-14 Regardless of factors and outcomes, data is lacking for accelerated programs, even though they may enroll students with similar backgrounds and levels of preparedness compared to those transferring into 6-year programs. The objective of this study was to identify the impact of selected prematriculation characteristics on the on-time graduation rates of students attending an accelerated PharmD program.

METHODS

Approval to conduct this research project was granted by the university’s institutional review board. Data were retrospectively gathered and organized from admission files of students who matriculated to the Worcester and Manchester (W/M) campuses of MCPHS University (formerly known as Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences) with anticipated graduation dates from 2009 to 2012. The Worcester campus of MCPHS serves as the main campus for the accelerated PharmD program, with approximately 250 current students in each of the 3 class years.

Telecommunications equipment links Worcester to the Manchester campus, at which another 50+ students are in each class year. Nearly 80% of the lectures are given by instructors on the Worcester campus, with the audio and visual information and presentation slides delivered to the Manchester students in real time. The remaining 20% of lectures are delivered by instructors from Manchester and broadcast to Worcester. Students and faculty members from both campuses are able to communicate freely over the connection to allow for discussion. Students are provided similar opportunities for academic support and assistance from faculty members regardless of which campus they attend classes. The distance education system has been used for approximately 10 years.

Information gathered from files of students attending the program on both campuses included students’ original and actual years of graduation from MCPHS W/M, previous colleges attended, degrees earned, overall GPA (calculated using all prematriculation, college-level coursework), math/science GPA (all math/science coursework), prepharmacy GPA (prerequisite courses for admission), previous pharmacy work experience, and whether students requested a waiver for acceptance of prerequisites for college credit earned more than 10 years before application to MCPHS W/M.

On-time graduation was used as a register of academic success and was defined as students graduating in the original year of their expected graduation from our 3-year program. We did not discriminate between reasons for not graduating on time, which may have been academic, personal, etc. Data were assessed for percentage of students with specific characteristics to graduate on time. Subanalysis was conducted within groups of students based on the presence or absence of characteristics using calculated odds ratios to identify the impact these factors had for graduating on time. Microsoft Excel 2010 was used to organize data and perform statistical analysis.

RESULTS

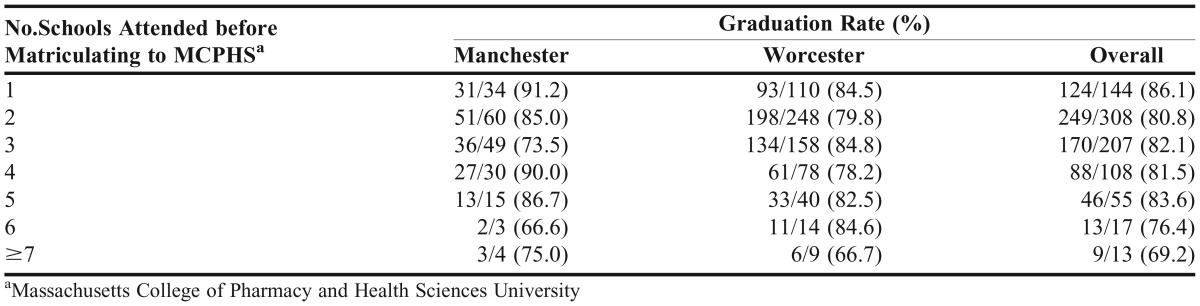

Overall, files of 852 students matriculating to the PharmD program between the 2 campuses were evaluated (Manchester n=195; Worcester n=657), and 699 (82.0%) graduated on time (Manchester, 163/195; 83.5%; Worcester, 536/657; 81.6%). The MCPHS School of Pharmacy is an accelerated program requiring applicants to complete a standard set of prerequisite courses for admission consideration. These include general chemistry, organic chemistry, microbiology, biology, physics, calculus, and others. Therefore, students who attend MCPHS W/M have previously undertaken a significant course load of higher education credit. Many students complete the prerequisite courses at one undergraduate institution, while others divide their course work among more than one school. The mean number of previous college-level schools attended by students in our cohort was observed to be 2.7 for those who graduated on time and 2.8 for those who did not (p=0.25). But a trend toward a reduced likelihood of graduating ontime was seen in students who earned credits from a greater number of schools and regression analysis confirmed this (r2=0.75; p=0.005, Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Graduation Rates Associated with Number of Schools Previously Attended

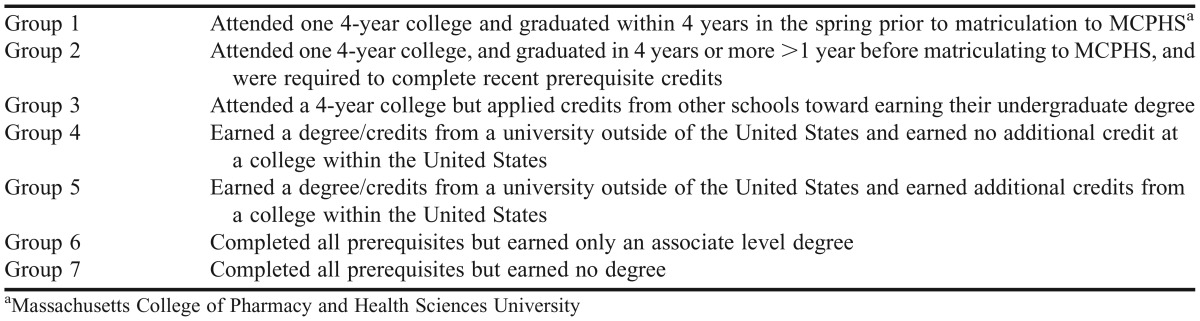

Based on the wide range of schools attended prior to MCPHS W/M, evaluation of the impact of attending a traditional 4-year undergraduate program on graduation rates was made. Full data describing from what institution students came and when they earned their degrees was available on only 827 candidates. Complete admission file information was available for the remaining 25 students, but in reviewing the files for this study, we were unable to determine the timing order for when they earned credit from the multiple schools they attended because of the absence of specific dates of attendance. Therefore, these students were not included in analysis for which this specific data was required. Students for whom full data were available were grouped based on whether they earned all of their undergraduate credits from one school, how much time passed between graduating and matriculating to MCPHS W/M, whether the institution was located in the United States, and what degree, other than a bachelor’s degree, may have been earned, if at all (see Table 2 for groupings).

Table 2.

Student Groups Based on Type of Institution From Which Prematriculation College Credits Were Earned

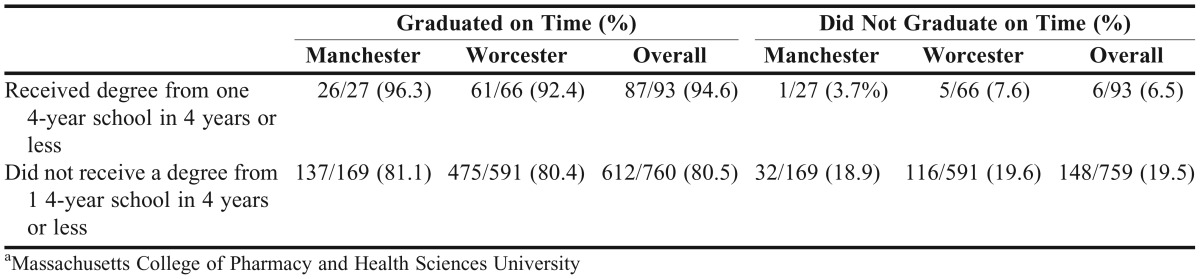

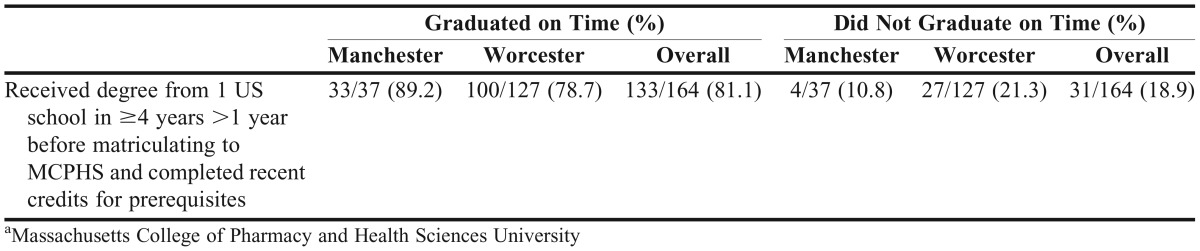

Only 93 students (10.9%) attended one secondary school and earned a bachelor’s degree in 4 years or less and entered MCPHS W/M in the fall following their springtime graduation (group 1). This group represented the students most likely to graduate from MCPHS W/M on time (94.6%) compared to all other students who did not meet this characteristic (612/759; 80.5%). A calculated odds ratio (OR) for on-time graduation based on this one characteristic significantly favored the students in group 1 (OR=3.48; 95% CI=1.49-8.12; p<0.05; Table 3). Interestingly, the on-time graduation success rate of students who earned a 4-year degree in 4 or more years with credits from one school, but had a break of at least one calendar year before matriculating to MCPHS W/M and/or were required to complete additional prerequisites to satisfy admission requirements (group 2) was only 81.1% (n=133/164; Table 4). This difference in on-time graduation between students who entered pharmacy school in the fall immediately after graduating from their undergraduate school and those for whom there was a delay was significant (OR=3.38; 95% CI=1.35-8.44; p<0.05).

Table 3.

Graduation Rates of Students Who Received Their Degree From One 4-Year School in 4 Years or Less Just Prior to Matriculating to MCPHSa

Table 4.

Graduation Rate of Students Earning a Bachelor Degree in ≥4 Years >1 Year Prior to Matriculating to MCPHSa

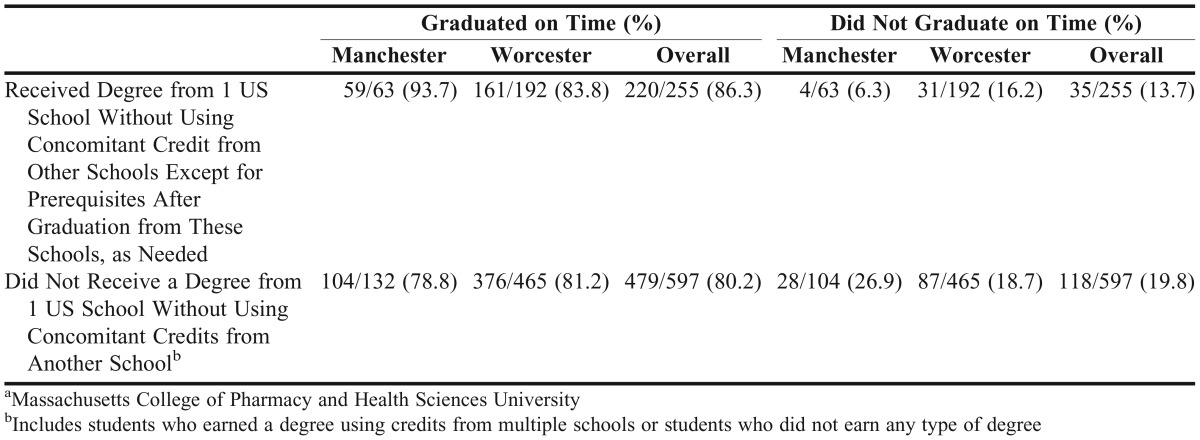

When considering all students who earned their 4-year degree from one school regardless of how much time elapsed between matriculation and graduation to MCPHS W/M (groups 1 and 2), again, these students had a higher percentage rate of on-time graduation compared to those students who earned their 4-year degree with credits from multiple schools (group 3, n=296/355), plus those students who did not earn a 4-year degree within the United States (groups 4-7, n=165/215) (85.6% vs 80.9%; OR=1.41; 95% CI=0.94-2.11; p=0.1), although this comparison was not significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Graduation Rates of Students Based on Earning a 4-Year Degree from One US School vs All Others (ie, 1 School vs >1 School) Prior to Matriculating to MCPHSa

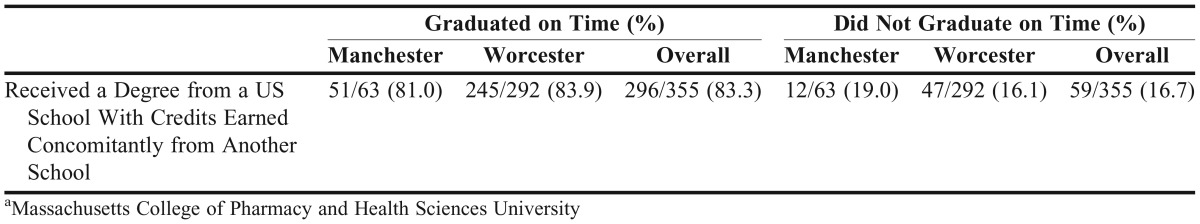

Many students attended 4-year colleges and earned degrees from these schools, but earned credits concomitantly at other schools, including community colleges, and applied these credits to the degree requirements of their primary school of enrollment (group 3). Many of these out-sourced classes were in the students’ major academic area of study. Of these 355 students, only 296 (83.3%) graduated on time (Table 6). These students were equally likely to graduate on time compared to students in groups 1 and 2 combined (OR=1.19; 95% CI=0.76-1.85; p=0.46). But when comparing students in group 3 to those in group 1, a significant difference was observed (OR=2.89; 95% CI=1.21-6.92; p=0.017).

Table 6.

Graduation Rates of Students Who Earned a Degree Applying Credits from Multiple Schools Prior to Matriculating to MCPHSa

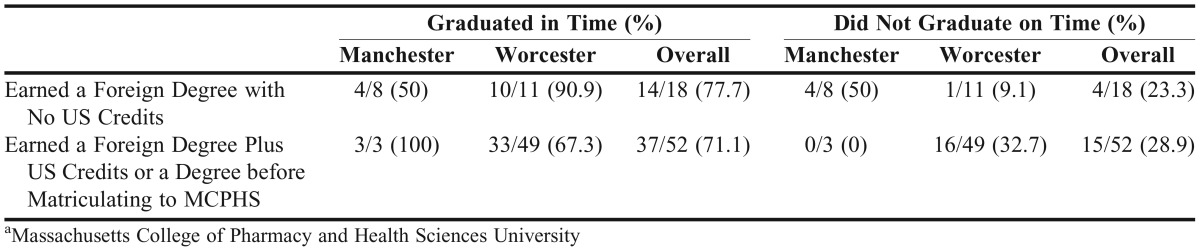

There were 70 students who earned a degree outside of the United States prior to matriculation to MCPHS W/M. Countries from which these students came included India, Sierra Leone, Iraq, Iran, Ghana, Vietnam, South Korea, Nigeria, Cameroon, Canada, Saudi Arabia, among others. Students who earned a degree outside of the United States were divided into 2 groups: those who earned no additional college credits (to their international degree) prior to matriculation (group 4; n=18) and those who earned additional college credits at a school located in the United States after they earned their degree in another country (group 5; n=52).

Students with only an international degree were 77.8% likely to graduate on time, while those who earned their international degree and then completed additional college level work in the United States were only 71.1% likely to graduate on time. Table 7 contains comparisons of students who earned their undergraduate degree within the United States with those who did not. Students who fell into group 5 (ie, international degree plus additional college-level credit within the United States) were less likely to graduate on time from MCPHS W/M than all other groups, including students who had no additional college experiences between earning their degree from an institution located outside the United States and matriculating to MCPHS W/M.

Table 7.

Graduation Rates of Students Who Attended Schools Outside of The US Prior to Matriculation to MCPHSa

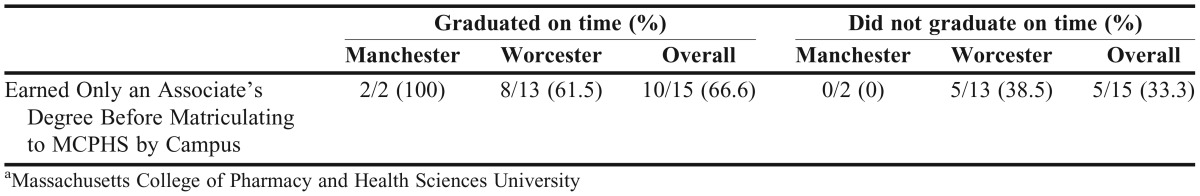

A small number of students attended only community college and earned only an associate-level degree prior to matriculation to MCPHS W/M (group 6). These 15 students were among the least likely to graduate on time (10/15; 66.7%; Table 8). Compared to students who had earned a 4-year degree, students with only an associate’s degree were at an academic disadvantage, but this was only significant when compared to those students who earned their degree from one 4-year institution in 4 years or less just prior to matriculating to MCPHS W/M (OR=7.25; 95% CI=1.87-28.12; p<0.05). Students in this latter category were the only comparator group with no attendance at a community college, as students in group 2 included individuals who often opted to complete remaining prerequisite credits at these types of institutions, and students in group 3 often supplemented their credits earned from their 4-year institution with credits from a community college.

Table 8.

Graduation Rates of Students Who Earned Only an Associate’s Degree Prior to Matriculation to MCPHSa

Finally, for those students who earned no degree (from either a bachelor’s or associate degree program), on-time graduation was somewhat similar (104/130; 80.0%) to those students in either groups 2 (81.1%) or 3 (83.4%). Many of these students earned their prerequisite credit from a 4-year undergraduate program and matriculated to MCPHS W/M following completion of their third year of school, but lacked that fourth year of college level experience. When comparing these students with no degree to group 1, they were less likely to graduate on time (OR=3.63; 95% CI=1.43-9.21; p<0.05).

Three grade point averages (overall, math-science, and prepharmacy) are calculated for all students during the admission process. To evaluate the impact of GPA, the 3 values were ranked into quartiles and rates of on-time graduation were compared (Tables 9a, 9b, and 9c) Higher overall GPA was associated with a higher likelihood of on-time graduation. To identify a GPA threshold that might help predict what GPA was most likely to predict success, groupings of ranked quartiles based on GPA were lumped together and analyzed. Regardless of how neighboring quartiles were lumped together (ie, first quartile vs second, third, and fourth, or first and second quartile versus third and fourth quartiles, etc), not surprisingly, the groupings made up of higher GPAs were always more likely to graduate on time.

In looking at the impact of prepharmacy GPA, the advantage is less clear. Students in the first quartile (ie, ≥3.68) were more likely to graduate on time than students in the third and fourth quartiles, and students in the top 2 quartiles (ie, >3.48) were more likely to graduate on time than students in the lowest quartile. But students in the first quartile were not more likely to graduate than the 3 other quartiles combined. Likewise, students grouped into the top 2 quartiles fared no better than their counterparts in the lower 2 quartiles, and the top 3 quartiles were not different from the fourth quartile. As mentioned, these groupings were made to try to identify a breakpoint of the impact of prepharmacy GPA on graduation, which appears difficult to identify with this metric. There were no significant differences in on-time graduation for any of the quartile comparisons regarding math/science GPA either.

Fewer than one-third of students (249/852; 29.2%) stated in their admission application that they had experience working in a pharmacy. Surprisingly, the impact on helping them graduate on time was not different compared to those students without the opportunity to work in a pharmacy (with experience, 207/249 [83.1%] vs no experience, 492/603 [81.6%]; OR=1.11; 95% CI=0.75-1.64; p=0.61).

The admission committee has a policy to only accept prerequisite credits that have been earned no earlier than 10 years prior to the application process. Candidates may submit a request to the admission office to waive this 10-year limit based upon extenuating circumstances they must explain in written detail. Ninety-nine students who matriculated during the period of study requested a waiver of the 10-year limit, and 68 of these students graduated on time (68.7%), which was lower than those students who either did not request a waiver or did not need to (OR= 2.36; 95% CI=1.48-3.76; p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

For any process in which individuals are selected to become part of an exclusive group based on identifiable characteristics, a systematic procedure must be created to facilitate the effective comparison of those being evaluated. Admission to college programs is typically based on the performance of applicants in previous academic programs, with the hope that past success in the previous environment translates to future success in the new environment. Admission committees generate their own methods to facilitate their work. This process is not unlike that seen in professional sports, in which players are selected by coaches and scouts based on the inherent qualities considered most likely to predict future success on the field.

In the book, The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance, David Epstein explains what makes elite athletes elite.15 Body type, trainability, and will to win contribute to making certain athletes better than others. But he also points to the incredibly complex interaction of factors that must align to create the opportunity for individuals with any of these characteristics to have a chance to achieve success.

Although mental make-up is a key factor of on-field success, easily measureable physical traits remain a key ingredient. In academia, the analogy to sports partially rings true in that admission officers, like coaches and scouts, are looking for that combination of characteristics they feel is most likely to lead to future success. But for college admissions, these characteristics are far more difficult to recognize and are even harder to measure. The hope is that the metrics used are an effective means to gauge an applicant and guess how well he or she will perform in the future. Unfortunately, predicting academic success based on measurable traits is flawed because of the inability to directly measure intellectual capability, which forces schools to rely on indirect measurements, such as GPA. Although one can calculate GPA, what this number means differs based on what courses are used in its calculation, how grades were determined in those courses, the competitiveness and academic rigor of the learning environment, what other courses were taken at the same time, and a host of other factors. The complexity becomes challenging and magnifies the difficulty in the admission process.

Identifying characteristics of a successful college student depends on the analysis of student data gathered from their numerous and different experiences. This introduces an incredible challenge to compare the educational opportunities and experiences of every applicant. Life-time experiences also mold the student and are as equally unique as any other characteristic used to guess at future academic success. Unlike sports, there are no body measurements or objective instruments such as strength and speed that provide easy indicators to help admission officers make their decisions. Instead, the admission process is forced to make decisions based on data generalization. Most of the time, admission decisions are successful in identifying students that achieve positive outcomes in the program of study. But without exception, factors not identified during the application process or that arose during participation in the program limit some students from meeting their goals. In academia, just as in professional sports, disappointing outcomes occur even in individuals with seemingly faultless traits otherwise consistent with success.

With the goal of giving the MCPHS admission committee data to support the decision making process, we reviewed the files of students from class years 2009-2012 who were granted admission to our program. Most files contained all the information needed to complete our analysis, but some files, although they contained all the typical information needed to make an admission-based decision, were missing information, such as specific dates when some students attended colleges other than the one at which they earned their degree. This limited our ability to include all students in all analytical comparisons. Nonetheless, we were able to build a database with substantive evidence to identify trends on how identifiable characteristics were associated with our primary outcome of on-time graduation. Another limitation was our inability to determine the exact cause to explain why each student did not graduate on time. Although nearly all of the delays happened for academic reasons, it is difficult to determine whether outside, nonacademic influences may have instigated the academic issues, or vice versa, that prevented on-time graduation.

The most successful students were those challenged by the academic opportunities offered through the consistent participation at one 4-year school. These students lacked factors that reduced the likelihood for on-time graduation, such as taking courses at other colleges, taking a longer period of time to earn enough credits to complete their undergraduate degree, repeatedly transferring from one school to another, or retaking classes in which they initially earned an unsatisfactory grade. It appears that the students who earned their degree from one school in 4 years are more prepared to deal with the challenges they will face in our accelerated program compared to those students who take a more circuitous route to their degree.

At MCPHS University, many students from countries outside of the United States select our program at which to earn their PharmD. Their contributions help create a more diverse environment of thought and culture at the university. Although the diversity of these students’ backgrounds contributes to the diversity of our school, it also makes assessment of their applications more complicated because of a lack of understanding for the academic rigor of schools these students previously attended. Overall, less than 10% of our students earned college-level credit at a school outside of the United States. Based on our analysis, these students are faced with academic challenges that reduce their probability for graduating on time from our program. Although most of these students (72.9%) graduate on time, there is some issue that prevents more than a quarter of them from meeting this outcome. One could surmise that learning in a secondary language could be the key contributor, but the exact reason remains unclear. Of those students with an international degree, those with no additional college-level experience in the United States prior to matriculation fared better than those who earned additional credits after their arrival in this country. An interesting feature of many of these latter students is that they attended community colleges to earn their prerequisite credits, which we have also identified as a factor that reduces the likelihood for on-time graduation. Therefore, the combination of earning a degree outside of the United States and then experiencing the environment of a community college as the sole example of how well they function in an English-only classroom may give admission officers a poor indication of these students’ academic competency even when the grades they earn appear to be satisfactory.

Interestingly, there were a portion of students (15.3%) who earned no degree prior to matriculation. All of these students completed the same prerequisites as all other candidates, but a broad range of factors that describe these students, many of whom had completed 3 years at one 4-year institution but decided to forego their senior year (and their degree) with the plan to graduate in what would end up being a year earlier with their PharmD. Other students attending MCPHS without a previous degree attended multiple schools to earn their prerequisite credit without any intention of earning a degree. The combination of a lack of the fourth year of an undergraduate program and the absence of academic consistency likely contributed to their lower rate of on-time graduation compared to those students with a complete and more consistent academic experience.

The benefit of having a 4-year degree in predicting success in schools of pharmacy is nothing new, and research supporting this finding dates back nearly 20 years.9,10,11,16 But our data are the first to link having this degree with on-time graduation in an accelerated PharmD program, in which the academic demands may be higher than those of a traditionally-paced program. The lack of rigor in previous educational experiences may be a detractor for some students. For example, those students who only attended a community college and earned only an associate-level degree prior to starting at MCPHS were far less likely to graduate on time compared to their counterparts that earned a bachelor’s degree from one 4-year institution. Although community colleges provide students with a lower cost and easily accessible opportunity for learning, the potential for a reduced level of competitiveness may limit their opportunity to build foundations of learning that are required to be successful in our program.

A surprising observation was the minimal impact offered to those students who stated in their applications that they had previous pharmacy experience. One would expect that having the opportunity to work in a pharmacy environment would give students an advantage over what they need to know and how better to apply what they would be learning in the classroom. But the expected value of this experience was not universally appreciated by students. Previous studies found that working in a pharmacy did contribute to better student performance in individual courses or retaining therapeutic information, but there was no additional data to support the impact in graduating on time.17,18 It is likely that some students who initially did not mention any pharmacy experience in their admission applications subsequently gained that experience, providing an inaccurate assessment in our analysis.

The attempt to identify those characteristics in pharmacy school candidates that best predict which students will be successful is well documented in the literature and include gender, grades in specific courses (eg, organic chemistry), age, high school or prepharmacy GPA, Pharmacy College Admission Test (PCAT) scores, prior degrees, ACT scores, attainment of a previous or higher degree, and others.2-6,8-14,16-19 Outcomes for most previous attempts to correlate a metric with academic success in pharmacy school were as varied and include academic probation13 or dismissal,14 yearly and overall pharmacy GPA,2-6,8-10 grade in a top 200 drugs course,18 clerkship GPA,2 Health Sciences Reasoning Test scores16, and North American Pharmacy Licensure Exam (NAPLEX) scores.3,12 Despite these attempts to clear the mud from the murky admission waters, the process is still far from ideal.

There are too many prematriculation factors that can be measured in too many ways from too many sources to allow for the development of a perfectly predictable system, and the difficulty in predicting human behavior based on past experiences is inherent. There was no factor in our research that predicted success 100% of the time; even some students with the best characteristics were not successful. Therefore, although educational pedigree is important, the best we can do is to apply general strategies to narrow our focus and appreciate the myriad experiences that contribute to the development of each individual applicant. Once the admission process has been completed, it is then the responsibility of the student and faculty members to facilitate success in the pharmacy education experience.

Our data can help other programs fine tune their admission processes. Identifying candidates who have done well in quality educational experiences appears to be a key factor in predicting success. Basing the final decision upon characteristics that make applicants the individuals they really are (eg, where they earned their degree, what experiences have helped shape their lives) would then be prudent. Our results, as well as those of other published studies, indicate identifiable characteristics help predict academic success, and we should be using these to identify applicants for enrollment. Likewise, potential applicants should be wary that not all prepharmacy college experiences are the same, and they should seek out programs that challenge their intelligence and help develop skills most likely to facilitate their future success.

There are several limitations to our study. As mentioned earlier, the lack of complete information on all students who matriculated into the program limited the inclusion of all students in some assessments of the information. Our admission data system has been updated since this project to prevent such recurrences. As noted earlier, we did not determine the reason for students who did not graduate on time. At least some of these students withdrew from the program for reasons unrelated to lack of academic success. Confidentiality policies prevented us from having the opportunity to properly identify these students but the impact remains.

We also did not present analysis of the impact of combinations of characteristics on student success because of the vast variety of different backgrounds that exist in our admission cohort. Such variety made combinations difficult to assess and could possibly have misdirected our intents, as well as raised concerns over proprietary admission practices that we employed. Finally, we did not evaluate many other factors that could influence academic success in our program, such as living on or off campus, studying in groups or alone, whether English is a second language, attending class regularly, and more. These provide ideas for future investigations.

Other research activities could include the development of an admission scoring rubric that uses our findings to select applicants with an acceptable concentration of the characteristics most likely to predict success. How each factor is weighted and what other tangible and intangible factors should be considered remain to be determined. Providing adequate academic support services is also important to help students become effective learners and meet the challenges of our rigorous program to become successful and competent pharmacists in the future.

CONCLUSION

Identifiable factors in pharmacy school applicants can be used to help predict future success in PharmD programs. Those applicants who attended MCPHS directly after earning a bachelor’s degree at one 4-year institution were most likely to graduate on time. Factors that limited on-time graduation included attending multiple schools, delaying application to pharmacy school, lower grade point averages, and having earned a foreign degree. But these factors cannot be used as the sole means to make admission decisions as other influences difficult to identify and measure affect student outcomes and prevent even the seemingly best qualified students from achieving their goals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor DA, Taylor JN. The pharmacy student population: applications received 2011-12, degrees conferred 2011-12, fall 2012 enrollments. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(6):Article S3. doi: 10.5688/ajpe776S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidd RS, Latiff DA. Traditional and novel predictors of classroom and clerkship success of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4):Article 109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuncel NR, Credé M, Thomas LL, et al. A meta-analysis of the validity of the Pharmacy College Admission Test (PCAT) and grade predictors of pharmacy student performance. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(3):Article 51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobb WB, Wilkin NE, McCaffrey DJ, Wilson MC, Bentley JP. The predictive value of a school of origin variable in pharmacy student academic performance. J Pharm Teach. 2007;14(1):79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCall KL, MacLaughlin EJ, Fike DS, Ruiz B. Preadmission predictors of PharmD graduates’ performance on the NAPLEX. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1):Article 05. doi: 10.5688/aj710105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meagher DG, Lin A, Stellato CP. A predictive validity study of the Pharmacy College Admission Test. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):Article 106. doi: 10.5688/aj700353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meagher DG, Pan T, Perez CD. Predicting performance in the first-year of pharmacy school. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(5):Article 81. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers TL, DeHart RM, Vuk J, Bursac Z. Prior degree status of student pharmacists: is there an association with first-year pharmacy school academic performance? Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2013;5(5):490–493. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unni EJ, Zhang J, Radhakrishman R, et al. Predictors of academic performance of pharmacy students based on admission criteria in a 3-year pharmacy program. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2011;3(3):192–198. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, Kotzan JA. Significant factors for predicting academic success of first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;59:364–370. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, Kotzan JA, Lautenschlager G. Prior four year college degree and academic performance of first year pharmacy students: a three year study. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61:278–281. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCall KL, Allen DD, Fike DS. Predictors of academic success in a Doctor of Pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):Article 106. doi: 10.5688/aj7005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houglam JE, Aparasu RR, Delfinis TM. Predictors of academic success and failure in a pharmacy professional program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(3):283–289. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardinger KL, Schauner S, Graham M, Garavalia L. Admission predictors of academic dismissal for provisional and traditionally admitted students. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2013;5(1):33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein D.The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance New York, NY: Penguin Group, Inc2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox WC, Persky A, Blalock SJ. Correlation of the health sciences reasoning test with student admission variable. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(6):Article 118. doi: 10.5688/ajpe776118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valdez C, Namdar R, Valuck R. Impact of pharmacy experience, GPA, age, education, and therapeutic review on knowledge retention and clinical confidence. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2013;5(5):358–364. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene JB, Nuzum DS, Boyce EG. Correlation of pre-pharmacy work experience in a pharmacy setting with performance in a top 200 drugs course. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2010;2(3):180–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schauner S, Hardinger KL, Graham MR, Garavalia L. Admission variables predictive of academic struggle in a PharmD program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(1):Article 8. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]