INTRODUCTION

According to the bylaws of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), the Advocacy Committee: “will advise the Board of Directors on the formation of positions on matters of public policy and on strategies to advance those positions to the public and private sectors on behalf of academic pharmacy.”

PRESIDENTIAL CHARGE

President Pat A. Chase presented the committee with the following charge:

With the pending reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, this is an excellent time to review how academic pharmacy is:

• Ensuring people have access to pharmacy education;

• Engaged in keeping it affordable; and

• Increasing both institutional, faculty and student accountability.

The 2014-15 Advocacy Committee will examine the topics of access, affordability, and accountability in pharmacy education and their alignment with these same issues across higher education.

Access. With attention to, but not limited to underrepresented minorities, describe best-practices at AACP member institutions that focus on individual access to both professional and graduate pharmacy programs. Topics for consideration include: state and federal diversity programs.

Affordability. With attention to, but not limited to tuition and cost of attendance, describe best practices of how AACP member institutions ensure the value of a professional or graduate degree. This description should discuss the return on investment of a pharmacy degree. Topics for consideration include: innovation in higher education; competency-based education; facilitated learning; distance education; interprofessional education.

Accountability. With attention to, but not limited to accreditation, describe best practices of how AACP member institutions hold themselves, their faculty and their students accountable for the creation and execution of a high-quality educational experience. Topics for consideration include: student assessment; faculty and program evaluation; regarding accreditation-evaluating institutional quality; the value of the peer review aspect of both regional and specialty accreditation.

PROCESS

During the AACP annual meeting, staff shared the Presidential charge with members and sought the participation of content-experts related to the three priority areas. Interested participants received a follow-up email asking them to verify both their interest and their expertise by sharing scholarly work with the Chair and staff. Staff also reviewed the member profile of the interested participant for inclusion of content-expertise.

In October 2014 these content-experts met during a face-to-face meeting of all standing committee participants. During this meeting the Chair and staff reviewed the committee charge and led the group through in a wide-ranging discussion of that charge. Committee members self-selected one of the three priority issues in which they would contribute their knowledge and expertise. Committee members with the same interest joined together into a priority issue workgroup. Using a draft report outline, committee members determined who would be responsible for specific portions of the report, what that portion would include, and a timeline for committee work.

The committee workgroups worked toward completion of their specified report portions sharing information and resources via email and phone calls. The committee as a whole held monthly conference calls to provide status updates, seek input from the entire group related to challenges, and review and modify accountabilities as needed. The outcome is a final committee report published in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, the highlights of which are presented at the AACP 2015 annual meeting.

The committee continued the work of recent Advocacy Committees in applying concepts and frameworks from implementation science to improve AACP’s advocacy efforts. As individuals and institutions increase the use of evidence-based interventions, these concepts and frameworks allow for the identification of successful intervention implementation. Specifically, the committee used the Hexagon Tool, discussed and tested by the 2013-2014 AACP Standing Committee on Advocacy, to evaluate individual and institutional ability to implement the core components identified with the three priority issues of affordability, access and accountability.1-2

Context: Public Policy and Higher Education

“Many college graduates are delaying some of life’s most important decisions – including starting a family and buying a home – because they face a pile of debt with no job prospects. A record number of young adults live with their parents and roughly half of college graduates under the age of 26 rely on mom and dad for financial help.”3

“In higher education, the U.S. has been outpaced internationally. In 1990, the U.S. ranked first in the world in four-year degree attainment among 25-34 year olds; today, the U.S. ranks 12th.”4

“To boil these concerns down to their core elements, our higher education system today faces three great challenges. They are: First, the price of a college education is too high.

Second, the college completion rate is too low. And third, there is too little accountability in higher education for improving attainment and achievement.”5

“Postsecondary education in the United States faces a conundrum: Can we preserve access, help students learn more and finish their degrees sooner and more often, and keep college affordable for families, all at the same time? And can the higher education reforms currently most in vogue – expanding the use of technology and making colleges more accountable – help us do these things?”6

“It is important to note something off the bat: Alexander is an avowed fan of our existing system of higher education, often touting it as the best in the world and arguing that we should reform our K-12 system to look more like higher ed (with its voucher-funded market and private providers). As such, expect healthy skepticism of reforms that would fundamentally change the relationships between the federal government, colleges and universities, and accreditation agencies.”7

The quotes above are from just a few of the possibly hundreds of documents focusing public policy attention on the issues of affordability, access and accountability in higher education. The charges levied against higher education are clear and consistent:

• Student debt now exceeds $1.2 trillion.8

• Tuition increases do not necessarily mean higher quality.9-10 Ronstadt R. High tuition doesn’t equal quality.

• Accessing information about the true cost of higher education is a challenge for students and parents.11-12

• Degree completion rates for students indicate an enterprise more interested in money than in education.13-14

• In 2012, 18% of job openings tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics require at least a baccalaureate degree and that percentage will increase slightly over the next decade.15

• Accreditation, whether regional or specialty, inhibits innovation and supports the status quo.16

Given these charges against higher education, the committee sought to determine how well academic pharmacy addresses these concerns and if any identified successes and challenges within academic pharmacy could be shared with public policy makers to help improve higher education in general.

A consistent approach to advocacy

In a continued effort to develop a consistent approach to the development of AACP’s advocacy agenda the committee approached its work in the following manner:

1. Placing the issue in context - Committee members reviewed a variety of documents to better understand and appreciate the public policy environment in regard to higher education.

2. Defining the issues- To evaluate the progress of the academy the committee discussed the need to find an existing definition for or define each of the three priority issues. This essential first step would provide the committee and readers with a clear statement of what it is we are attempting to address.

3. Describing core components- Agreeing to a set of core components necessary to attain that defined issue was a next step. To keep the committee’s work evidence-based, each priority issue workgroup reviewed the literature for evidence supporting an individual core component. Committee members individually reflected on his or her institution’s ability to implement each of the core components related to affordability, accountability and access.

4. Identifying strengths and weakness related to implementing core components- Using the Hexagon Tool the group discussed which, if any, of the six elements of capacity, readiness, evidence, resources, fit and need contribute to their institutions’ ability to implement the core components they had identified for addressing access, accountability, and affordability both individually and comprehensively.

Definitions

Affordability. For students and their families, pharmacy education is affordable if they are able to self-sustain their living expenses with a reasonable standard of healthy living during and after enrollment with adequate time for school work, self and family. For society, it is affordable if cost is not a significant barrier to credential attainment and if the education is efficient in producing significant societal benefits.17 For advocacy purposes, a benchmark could be identified, such as “pharmacy education is considered to be affordable when 90% of students would matriculate and complete a pharmacy program if admitted.” The actual metric will depend upon whether we want to assure that students can afford the lowest-price option or assure that all students can choose among any institutions for which they are academically prepared, regardless of price.

Accountability. Accountability of pharmacy education can be defined as: transparent communication to relevant stakeholders of the goals, outcomes and value of pharmacy education and evidence that supports these assertions. Stakeholders include students, the University, patients, faculty, the profession, society, government, legislators, accrediting agencies, employers, and the media. Accountability is a loop beginning at the back end of ensuring society is aware of the value of the pharmacy profession and of the product of pharmacy education i.e., the graduates or entry level pharmacists to society.

Access. Access to pharmacy education can be broadly defined as the availability of pharmacy education to anyone with the intellectual capacity and humanistic orientation to be successful as a pharmacy practitioner. If defined in this manner, then anything which prevents a ‘qualified’ individual from completing a course of professional study can be considered an access barrier to pharmacy education.

CORE COMPONENTS

“…we use the term core components to refer to the essential functions or principles, and associated elements and intervention activities (eg, active ingredients, behavioral kernels; Embry, 2004) that are judged necessary to produce desired outcomes.”18

Having provided a definition for each of the three priority issues the committee discussed the essential elements that must be available so that the outcome related to the respective priority issue has a reasonable chance of being accomplished. These essential elements can be referred to as core components. Given that there may be other definitions of any of the three issues being discussed in this report, we remind the reader that the core components listed here are deemed appropriate for the issue as defined in this report.

When we enter a discussion such as: Is higher education affordable? How do we increase institutional and student accountability? or, What improvements to public policy can ensure access to higher education for qualified individuals?, discussants should be prepared to share some empirical validation for the core components that can be attributed to the pre-determined outcome. The core components also need to be continually evaluated against the pre-determined outcome so that their attribution to the outcome remains valid.

For the definitions presented above, the committee offers the following core components for each of the three issues relevant to this report:

Affordability

1. True, absolute cost transparency

2. Predictability, uncertainty and risk of investment

3. True, short and long term value of education

4. Individualization

5. Educational Efficiency

Accountability

1. Strong and stringent accreditation standards

2. Institutional compliance with accreditation standards

3. Internal accountability

4. Novel pedagogies

5. Continued professional development

6. Recruitment and retention of quality faculty

7. Continuous attention to curricular alignment with changing societal needs

Access

1. Student academic preparation

2. Student financial capacity

3. Personal and institutional culture

4. Geographic placement of student and institution

EVIDENCE ASSOCIATED WITH CORE COMPONENTS

AFFORDABILITY

True Absolute Cost Transparency.19 Through transparent, clear, and effective communication, potential applicants are aware of the true life cycle costs of a pharmacy education. Costs include, among other things, opportunity cost of forgone wages, the true cost of tuition, loan interest, fees, books, room and board. There is ample evidence that college students have little awareness of their financial circumstances. Very few people actually pay the “sticker price.” If students knew the real costs, they would be more likely to enroll. The true cost is usually less due to the availability of:

• Tuition discounts

• Scholarships

• Grants from federal, state, and local entities

-

• Public and private loans with different repayment options

○ Income based repayment

○ Income sharing for a defined period of time with an investor

○ Monthly fixed payments

○ Loan forgiveness

• Tuition tax credits20

Predictability, Uncertainty and Risk of Investment. Applicants cannot be certain that enrollment in higher education will produce the desired returns. Students encounter academic, economic and personal issues along the way that may impact their ability to graduate on time, if at all. There is no assurance that they will be able to pursue their chosen careers. Risks of economic difficulties such as unemployment may make it difficult to repay loans on time. It is important to provide information for prospective students to evaluate and mitigate their risks by:

• Publishing likelihood of completion versus entering GPA, standardized test scores and other measures of readiness, weekly employment hours, commute distance and other measures21

• Educating students about loan repayment options (eg, income based, income sharing, standard repayment)22

• Teaching students financial management

• Teaching or facilitating students to navigate financial aid

• Providing information about the availability and effectiveness of academic support systems including advising, tutoring, mentoring, care for dependents, opportunities for work study

• Providing career services

• Providing summer bridge programs, learning communities, academic counseling

• Providing special supports for students from economically disadvantaged groups who confront additional problems23

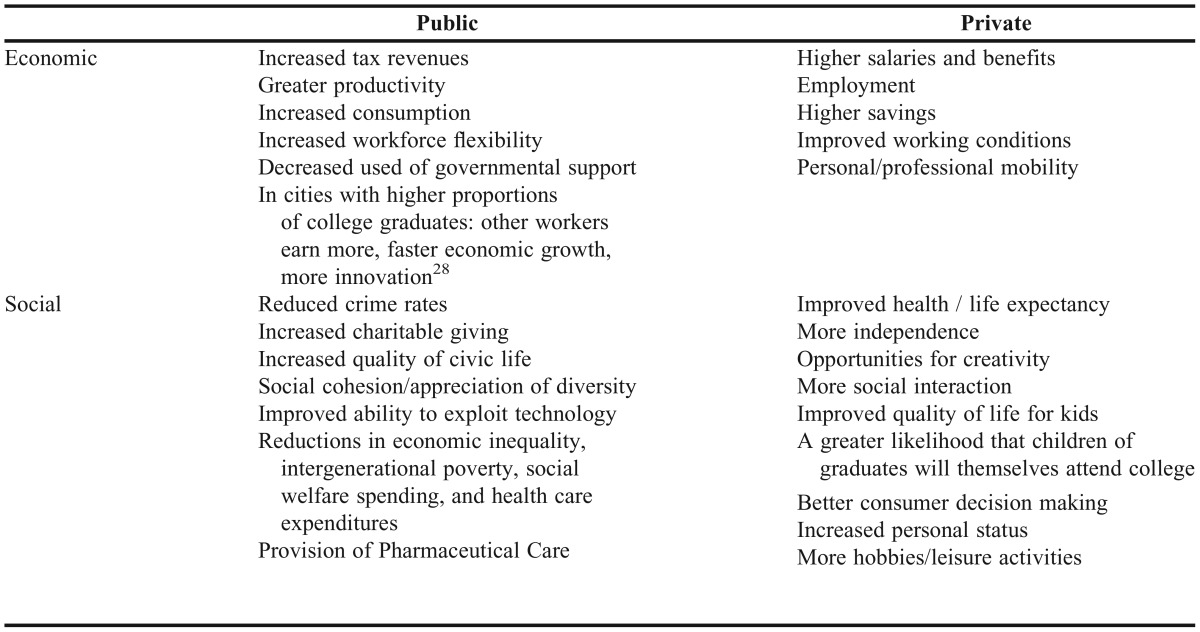

True Short and Long Term Value of Education24-25

This core component associated with affordability is a conclusion by the members of the affordability workgroup based on their analysis of the “life cycle net cost versus the benefits of pharmacy education.26-27

Table 1.

Individualization. The evaluation of affordability is unavoidably subjective and is influenced by both individual and cultural factors and preferences. These include:

• Access to credit.

• How much risk or credit is acceptable.

• Who bears responsibility for economic support of family members (child or parent).

• Faith in society / government.

• The degree to which they believe that education is an essential right versus a luxury.

• Relative value of all goods and services.

• Additional constraints including time, more unmet needs, less access to social services, more health challenges, food insecurity, etc.29

Educational Efficiency. The ways in which higher educational value can be produced at lower cost through:

• College credit for high school courses.

• College credit for learning outside the classroom (“testing in”).

• Competency-based education.

• Charging tuition only for faculty workload associated with teaching (eg, paying for research time with grants).

• Providing less costly alternatives, for example larger classes.

• Accepting transfer from community colleges.

• Supporting employment pipeline.

• Balancing enrollment with workforce demands.

• Increasing demand for graduates through marketing and lobbying efforts.

• Linking curriculum and credentialing to societal demand for knowledge, skills and abilities.

• Unbundling (eg, using educational designers and instructors rather than traditional faculty roles).

• Use of teaching assistants and adjunct faculty.

• Educational technology has so far not decreased costs – although there is evidence that it is at least equal to traditional methods in effectiveness.

• Decreasing costs through fewer amenities, options, flexibility, employee benefits.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Strong and stringent accreditation standards. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) is the national agency that accredits pharmacy professional degree programs. ACPE’s mission is to assure and advance quality in pharmacy education. ACPE continually updates its standards in keeping with the dynamic health care and education environments.30

Institutional Compliance with Accreditation Standards

-

• The percentage of new accreditations and accreditation renewals granted each year/cycle by ACPE demonstrates pharmacy education’s commitment to quality programming.31 In addition, accredited pharmacy programs are required to disclose program quality information to the public on their website, including:

Internal Accountability. There is a continued emphasis on internal accountability of pharmacy programs as seen by scholarly presentations and publications in the literature.

• Colleges/Schools of Pharmacy use assessment data to demonstrate accountability to external stakeholders and to prompt curricular change ultimately improving student learning.34

Novel Pedagogies. Continual improvement and innovations in teaching modalities to improve learning, critical and analytical thinking, problem solving and knowledge retention; that prepare practice-ready graduates.

-

• Active learning. Literature supports the use of active-learning in pharmacy education

- ▪ The AACP Curricular Change Summit encouraged pharmacy faculty to implement active learning strategies.35,36

- ▪ Improves retention, knowledge, thinking ability and problem-solving and fosters development of professional traits.

○ The ACPE Standards encourage the use of active learning strategies throughout the curriculum to enhance student learning and achievement of learning outcomes.37

○ Active learning strategies have been shown to increase the retention of pharmacotherapy core content.38

• Evidence-Based Practice incorporating critical thinking and problem solving.35

-

• New models for Health Professions Education

○ Competency-based inter-professional learning embedded in the workplace where health outcomes and educational outcomes are directly linked.39

• Academic pharmacy has been at the helm in interprofessional education (IPE) as part of the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC). There is documented leadership in incorporating and implementing this concept among various schools/colleges of pharmacy.40

• Modalities such as active learning and evolving assessment are being tested at various institutions with positive results.38,30

Continued Professional Development. Activities that promote lifelong focus on learning through experience, engagement in professional associations and advocacy for the profession.

• There is more a focus on continued professional development beyond the PharmD program, as academic institutions extend and expand experiential programs and their scope by providing continuing education to graduates who are now in practice.

• The Center for Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes 2013 emphasizes personal and professional development.41

• Students must be held accountable for their behavior in and out the classroom.42

• There is more effort at engaging student pharmacists in professional advocacy, both local and national, with a view to increasing value for patients, societal awareness and role recognition.35,43

Recruitment and retention of qualified faculty

• Americans believe that the quality of the degree and the quality of the faculty are two very important factors when selecting a college.

• 75% of Americans say the quality of the faculty are very important.

• Faculty development and peer assessments help ensure recruitment and retention of quality faculty.44

Continuous attention to curricular alignment with changing societal needs

• Programs continually assess their pre-pharmacy curriculum.

• An increase in prerequisites to match the increased need for maturity and quality of applicants led to a temporary decrease in applications.45

-

• Competency-based education

○ Moves from a structure and process-based curriculum to an outcomes-based curriculum; focuses on accountability and curricular outcomes; promotes individualized learning; de-emphasizes time-based learning.46

• Lawmakers want to hold colleges accountable for student learning and protect students and taxpayers from waste and fraud.47

ACCESS

Over the past 20 years, the discussion around access to pharmacy education has significantly changed. In the late 1990s, a nationwide shortage of pharmacists existed, created by increased demand secondary to growth in marketed prescription medication coupled with an aging population and exacerbated by the shift of pharmacy education to the Pharm. as the entry-level practice degree. In a report to the US Congress in 2000, the Department of Health and Human Services outlined the issues behind the shortage (including the mandated shift to the PharmD degree) and recommended several measures to alleviate it, including the need to expand pharmacist training opportunities and/or allowing more foreign pharmacy graduates to practice in the US.48

In response, pharmacy education began a period of unprecedented expansion, with many existing programs adding seats and new programs starting up such that the number of accredited program grew from 72 in 1987 to 133 as of January 2014 and the number of pharmacy graduates per year expanded from slightly over 8000 in 1996 to 13,207 in 2012-13.49

Visibility of pharmacy as a profession and a career choice also grew, through the promotional efforts of organizations such as the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), individual colleges of pharmacy and pharmacy advocates both internal and external to the profession.50,51,52 All of these efforts successfully increased the supply of pharmacists, although there were (and are) persistent barriers to pharmacy education for certain groups of individuals, particularly minorities and individuals from rural areas of the country. According to the Census Bureau’s 2006 American Community Survey, Blacks, Latinos and Native Americans comprised 28% of the US population at that time. Only 12% of the Pharm.D. degrees conferred in 2006 as first professional degrees, however, went to persons of Black, Latino or Native American heritage.53

In 2008, Dr. Barbara Hayes, then Chair of the Council of Deans for AACP, discussed the need to recruit and retain more minority students in pharmacy education and listed some of the barriers, which included a lack of preparation for college education and dwindling financial aid.53

Dr. Hayes also hinted at the potential negative impact on minority students of future changes in pharmacy education, such as an increase in the pre-professional requirements and the movement of some schools towards requiring a baccalaureate degree prior to admission to the professional program – changes that are now occurring in a number of colleges of pharmacy across the country. While these changes may have a greater negative impact on minority students, they will have some level of impact on all candidates for pharmacy education and could significantly restrict and/or reduce educational opportunities for a number of students.

If we examine the issues that currently drive access to pharmacy education, they can be grouped into 4 core components: 1) the level of student preparation needed to achieve admission to a school/college of pharmacy; 2) financial issues related to the total cost of the educational program and the perception of risk vs. benefit; 3) the cultural environment of a typical professional school and the extent to which students receive needed support during strenuous periods of the program and 4) geographic barriers due to the lack of programs in proximity to where the individual is located. Many schools/colleges of pharmacy attempt to address specific access drivers, but rarely in a comprehensive manner.

Student preparation

Most schools/colleges of pharmacy have a 2+4 curricular design, requiring at least 2 years of pre-professional work at the college/university level before entry into the 4 year program of professional study. The 2 years of pre-requisite study are usually heavily focused on math and sciences, including calculus, general biology, general chemistry and organic chemistry. As the profession has moved away from a dispensing model to a patient service model, however, additional competencies and skills sets have become necessary for the student to master prior to licensure.

With limited amounts of time and credit hours available at the professional level, many colleges of pharmacy have chosen to require longer pre-professional programs, up to and including requirement of a baccalaureate degree before admission to the professional program.54 Additionally, there has been a great deal of discussion around the level of preparation and maturity of a student with only 2 years of pre-professional work.55,56,57,45 While these issues are valid and deserving of discussion and debate, there must be consideration of the potential negative consequences of extending the pre-professional program on access to pharmacy education.

According to an analysis of the PharmCAS applicant data from 2008, females, non-underrepresented minorities and candidates whose parents attained a doctoral degree were accepted at higher percentages into colleges of pharmacy.58 It is likely that extending the pre-professional program will further disadvantage minority students, first generation college students and students from lower income families, as their investment of time and resources prior to being admitted to a college of pharmacy would be greater. Also, lower income and minority students make up a larger percentage of students at community colleges vs. 4-year colleges.59 It will become even more important for those students to have continued exposure to sound academic advising to navigate the pre-professional requirements of their desired schools in the minimum time frame and keep abreast of shifting admissions requirements.

Financial concerns

Although financial concerns are discussed more thoroughly in this report’s section on affordability, it is important to note that they don’t exist in a vacuum and are significantly influenced by factors such as the total length of the educational program (including pre-professional, professional, and post-graduate segments), the existing job market for graduates, and the economic status of the individual candidate.

It has been documented that these issues play a role in the decision of students to pursue pharmacy education (and higher education in general) and are more prominent in that decision for minority students and lower-income students.60,61 Financial issues for pharmacy students will also be impacted by the newly enacted limits on financial aid for graduate and professional degree students.62 The clock on eligibility for financial aid begins at the time a student starts their first undergraduate semester, so it is even more important that students desiring to pursue pharmacy education receive appropriate information and advising early in order to structure their educational program properly.

Cultural environment

In 2004, the Sullivan Commission reported that ethnic concordance between patients and their health care providers led to better patient outcomes and a higher perceived quality of care.63 As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, it is important for the healthcare workforce (including the pharmacist workforce) to diversify as well. As discussed in previous sections, however, diversification of the pharmacy educational environment has been difficult to achieve, for a number of reasons. While there has been a great deal of investigation around factors such as student preparation and affordability, one of the factors receiving more attention is the ability of a college to provide social networking and cultural support for multicultural students.

Several recent studies examining academic performance of minority students in health professions have noted this factor as being linked to academic success.64, 65 There is ongoing work at Stanford University to characterize the relationship between social support and academic success in higher education overall. Programs that have developed specific initiatives to recruit and retain minority students, such as the Office of Recruitment, Development and Diversity Initiatives (ORDDI) at UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, have also reported the importance of mentorship and networking opportunities in order to achieve success in minority recruitment and retention.66

Geographic location

Although there has been significant expansion in the number of accredited colleges of pharmacy around the country, there are still four states without a college of pharmacy and 13 states where there is only one. Most of the states where there are few colleges of pharmacy are in the Western region of the country and are states where there are large tracks of unpopulated land. Even in states where there are a substantial number of programs, such as Illinois, those programs are not necessarily spread equally across the state. Of the six programs in Illinois, five are located within the Chicago metropolitan area (one has a second campus in the Rockford area, NW in the state) and the sixth is in the St. Louis metropolitan area – leaving the entire central area of the state without a college in close proximity.

Given the realities of today’s economy, many students are staying at home during at least a portion of their college years either by choice or necessity. If home is located in a rural area or in a state with few COPs to choose from, then the student may find themselves with no options other than to relocate or to forego pharmacy education. A number of schools of pharmacy have instituted initiatives to address this issue, including opening distance campuses around the state, such as the University of Florida or, in a few instances, in different regions of the country, such as Midwestern University, with campuses in Chicago, Ill., and Glendale, Ariz. Another initiative is the development of a fully online PharmD program, which only two colleges of pharmacy now offer – Creighton University COP and LECOM COP.

How well are we doing?

The committee found it challenging to find consensus-based definitions for any of the three issues. Without definitions to establish a baseline for discussion, each workgroup created their own definitions to guide their work and as a way to discuss their work with others. Taking into consideration the relevant core components, committee members reflected on their individual institution’s ability to successfully implement a comprehensive approach to the issues of access, accountability and affordability.

This reflection provided the opportunity to identify institutional strengths and challenges related to successful implementation of the core components. By applying the six elements of the Hexagon Tool (need, fit, resources, evidence, readiness, capacity) committee members were then able to more completely describe the challenges the academy as a whole faces in successful implementation of the core components associated with the three issues of access, accountability and affordability. By describing the challenges, AACP is better positioned to influence public policy that may be developed to assist all of higher education in general and pharmacy education specifically, addressing these three priority issues. The 2013-2014 Advocacy Committee report defined the description of these challenges as advocacy action points.

So, how are we doing? Given that the committee represents a very small number of member institutions, it does include private and public institutions as well as institutions that attract students from urban or rural communities. Keeping the small sample size in mind, when compared and contrasted with the key public policy documents reviewed by the committee, in general the academy is concerned with and actively engaged in efforts to improve affordability, accountability and access to pharmacy education. These efforts are readily translated to higher education in general.67,68,69

Based on personal knowledge and reflection of their individual institutions, committee members indicated that none of their institutions comprehensively implements all the core components associated with the respective priority issue. Committee members were able to identify specific core components associated with each priority issue that are successfully implemented at their institutions. Likewise, committee members also identified specific core components that are a challenge for their institution to successfully implement. With the challenges identified, the committee proceeded to identify potential advocacy action points. These advocacy actions points are identified by using the Hexagon Tool to help answer the question: What keeps my institution from successfully implementing the core component?

The Hexagon Tool can be used to provide insight to an individual or institution about the ability of an organization to successfully implement a particular evidence-based strategy, or in our exercise the evidence-informed, core components associated with the respective priority issue. In this particular report, the committee applied the Hexagon Tool elements to the core components they associated with the respective priority issue of affordability, accountability or access.

Need. The identified needs of individuals are met through the implementation of this particular evidence-informed core component.

Fit. The implementation of the core component fits with current initiatives, priorities, structures and supports, and my institution’s values.

Resources. My institution has the resources necessary for training, staffing, technology support, data systems and administration to successfully implement the core component.

Evidence. There is sufficient evidence that the expected outcome associated with successful implementation of the core component will also be the outcome at my institution.

Readiness. Successful implementation of a core component has been replicated at institutions like mine and there is sufficient expert assistance from successful implementers to increase the likeliness of successful implementation at my institution.

Capacity. My institution is prepared to implement the core component as intended, based on evidence and readiness, and to sustain and improve the core component over time.

Reflection and element matching:

Affordability

All committee members indicated that the following core components of affordability are strengths of their institution:

• True, absolute, cost transparency; and

• Predictability, uncertainty and risk of investment.

To improve cost transparency, and predictability, uncertainty, and risk of investment, institutions use a number of strategies, including:

• Rolling all costs and fees into one fee;

• Charging the same tuition for in-state and out-of-state students;

• University-wide commitment to supporting under- represented minority students and first-in-family students;

• Data-driven financial aid and career counseling;

Committee members identified challenges related to implementing most of the specific core components related to affordability. Resource and capacity were the most common elements identified that provide a rationale for an institution’s implementation challenge. Evidence, related to the predictability, uncertainty and risk of investment, was identified as of increasing importance for an ability to predict student success and to improve career counseling.

Accountability

Strong accreditation standards and compliance with those standards are well supported by committee members offering some insight into the value of accreditation as a process for quality improvement. The core component of accountability identified by all committee members as an institutional strength was continuous attention to curricular alignment with changing societal needs. This is a strength when there is a strong commitment to continuous quality improvement across the institution.

Challenges to and the Hexagon Tool element related to implementing the core components of accountability included:

• The structure of strong and stringent accreditation standards requires commitment to a process/structure that does not fit well with innovation (Fit);

• The structure of strong and stringent accreditation standards focused on inputs limits institution and student interest in structure focused on educational outcomes (Fit);

• Institutions find a lack of evidence regarding effective assessment frameworks and strategies that align with accreditation standard compliance (Evidence);

• Evidence was also associated with institutional use of novel pedagogies (Evidence);

• Internal accountability remains a challenge as institutions attempt to balance cost and quality (Capacity, Resources);

• In some institutions faculty development is deemed optional and in others heavy teaching loads limit faculty ability to pursue development activities (Resources, Capacity).

• Limits to institutional activities related to the recruitment and retention of qualified faculty, especially faculty with teaching skills that can improve student leadership and critical thinking skills (Need, Resources).

Access

Committee members identified personal and institutional culture as a strength of their institutions. Institutional fit, or a commitment to creating a welcoming, supportive environment for both students and faculty was recognized as the reason for this type of institutional culture that supports diverse student and faculty.

Student financial capacity remains a challenge for most committee member’s institutions. Fit, readiness and resources were identified as the Hexagon Tool elements that may influence institution ability to impact this core component of access. Institution structures and processes fail to share important financial data such as undergraduate loan debt with professional programs. This lack of data sharing makes it difficult for professional programs to start financial aid counseling from an appropriate baseline.

Some institutions are simply not aware of best-practices related to effective financial aid counseling and therefore remain challenged by their own readiness to implement this core component. Resources was identified as the element that negatively impacts an institution’s ability to address access comprehensively and the implementation of individual core components.

CONCLUSION

AACP is interested in influencing the development of public policy that supports the implementation of evidence-based interventions. To accomplish this, a consistent approach to the development of advocacy strategies must be developed. Over the last three advocacy committee reports, AACP members and staff have worked to identify and test that consistent approach. The science of implementation offers one approach that provides an outcome satisfactory to our organizational interest.

If one aspect of public policy is to build community capacity to use evidence-based interventions, in their broadest definition, identification of reasons why communities succeed or fail to achieve that capacity is important. The concepts of implementation science may help communities, in their broadest sense, to influence public policy makers to accommodate the identified gaps in ability to implement in public policy they may be developing.

By using certain aspects of implementation science that include: developing consensus as to the context of the public policy, identifying the intervention to be implemented, breaking the intervention into its core components and using an implementation readiness framework such as the Hexagon Tool, communities, including colleges and schools of pharmacy, can improve the development of public policy the community deems important.

There appears to be general agreement that affordability of, accountability in and access to pharmacy education specifically, and higher education in general, are important public policy issues. The discussions that make up this report indicate that agreement with the context of the issues does not readily lend itself to an institution’s ability to effectively and efficiently implement mandates, structures and processes that may be part of legislation or other regulation emanating from public policy. Committee members found it difficult to find consensus-based definitions of any of the three priority issues.

This makes it difficult to move from a general discussion of context to one that provides specific, consensus-based definitions to which appropriate evidence-based interventions can be connected. If we support the development of evidence-based public policy, it appears that agreement as to what we are all talking about is an imperative. Contextual agreement provides the opportunity for communities and public policy makers to then identify the appropriate intervention, select or develop core components essential for recreating the intended outcome of the intervention and most important to the success of public policy, identification of advocacy action points by using an implementation readiness framework such as the Hexagon Tool.

Advocates may be able to better influence public policy when there is a consistent approach to assist them with the development of advocacy strategies. AACP members can effectively use the approaches discussed, tested and reported in this and past advocacy committee reports to develop those advocacy strategies.

As to the specific charges to this committee, the committee recognizes that our member institutions are committed to addressing the issues of affordability, accountability and access. This report provides some evidence that our institutions are actively engaged in the development of processes and structures to actively address these issues. The strengths presented in this report indicate that there are best practices to be shared.

There are also some very significant challenges for institutions to comprehensively implement the core components of the three priority issues in a sustainable and scalable manner. The academy would benefit from focused attention to data collection and evaluation that would provide institutions with the necessary evidence to meet many of the core components. Accomplishing this evidence development will remain a challenge for institutions as resources necessary to collect and evaluate data remain constrained at the federal and state levels.

REFERENCES

- 1. The Exploration Stage: Assessing Readiness. National Implementation Research Network. http://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/learn-implementation/implementation-stages/exploration-readiness. Accessed on March 13, 2015.

- 2.Bell HS, Albano CB, Kennedy KB, Young V, Lang WG staff liaison. Report of the 2013-2014 AACP Standing Committee on Advocacy: improving advocacy through the use of implementation science concepts and frameworks. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;Volume 78(10) doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810S20. Article S20. http://www.ajpe.org/doi/full/10.5688/ajpe7810S20. Accessed on March 13, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Representative Virginia Foxx (R-NC), ICYMI: The Student Loan Debt Solution Is All About Jobs. September 9, 2014. http://edworkforce.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=392820. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- 4.Higher Education, Office of the President of the United States. http://www.whitehouse.gov/issues/education/higher-education. Accessed on January 26, 2015.

- 5.Duncan A. US Department of Education, The Coming Crossroads in Higher Education. http://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/coming-crossroads-higher-education. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- 6.Rouse CE. The Postsecondary Conundrum. http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2013/06/05-postsecondary-education-schools-rouse. Accessed on January 26, 2015.

- 7.Kelly AP. What to Watch for in 2015: Higher Education Edition. http://www.aei.org/publication/watch-2015-higher-education-edition/. Accessed on January 26, 2015.

- 8.Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/student-debt-swells-federal-loans-now-top-a-trillion/. Accessed on March 13, 2015.

- 9.Ronstadt R. High tuition doesn’t equal quality. Forbes. March 10, 2009. http://www.forbes.com/2009/03/10/college-debt-smart-shoppers-personal-finance-retirement-ronstadt.html. Accessed on March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Not what it used to be. The Economist. December 1, 2012. http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21567373-american-universities-represent-declining-value-money-their-students-not-what-it. Accessed on March 13, 2015.

- 11.Weston L. Why it’s so tough to find out the true cost of college. Money. November 24, 2104. http://time.com/money/3602611/find-college-net-price-calculator/. Accessed on March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lederman D. The Spellings Plan – an interview with Margaret Spellings. Inside Higher Education. September 26, 2006. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2006/09/26/spellings. Accessed on March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graduation rates. Fast Facts. US Department of Education. Available at http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=40. Accessed on March 13, 2015.

- 14.Korn M. Big Gap in College Graduation Rates for Rich and Poor, Study Finds. Available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/big-gap-in-college-graduation-rates-for-rich-and-poor-study-finds-1422997677. Accessed on March 13, 2015.

- 15. Education and training outlook for 2012-2020. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_edtrain_outlook.pdf. Accessed on April 1, 2015.

- 16.Higher Education Accreditation Concepts and Proposals. US Senate Committee on Health, Education and Pensions. March 25, 2015. Available at http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/Accreditation.pdf. Accessed on April 27, 2015.

- 17.http://www.ihep.org/research/publications/college-affordable-search-meaningful-definition

- 18.Blase K, Fixen D. (2013).Core Intervention Components: Identifying and Operationalizing What Makes Programs Work. ASPE Research Brief. http://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/ASPE-Blase-Fixsen-CoreInterventionComponents-02-2013.pdf. Accessed on February 18, 2015.

- 19.http://r.search.yahoo.com/_ylt=A0LEVrxxd8ZUXYgAxTEnnIlQ;_ylu=X3oDMTEzdXI4YXFnBHNlYwNzcgRwb3MDMQRjb2xvA2JmMQR2dGlkA0ZGQUQwNF8x/RV=2/RE=1422321651/RO=10/RU=http%3a%2f%2fwww.brookings.edu%2fresearch%2fpapers%2f2014%2f11%2f12-transparency-in-college-costs-levine/RK=0/RS=w3lDvjOfkrc996qEQ.gY3ig45jU-

- 20. http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2014/12/11-chalkboard-real-student-lending-crisis-akers In one study, only a bare majority of respondents (52 percent) at a selective public university were able to correctly identify (within a $5,000 range) what they paid for their first year of college. The remaining students underestimated (25 percent), overestimated (17 percent), or said they didn’t know (7 percent)

- 21.http://www.betterhighschools.org/CCR/resources.asp

- 22.edworkforce.house.gov/uploadedfiles/hea_whitepaper.pdf

- 23.http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/journals/journal_details/index.xml?journalid=79

- 24.http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/journals/article/index.xml?journalid=79&articleid=580

- 25. Value Metrics include: Percent graduates get “good” jobs, or the jobs they wanted; Average starting salary and salary increase for varying career tracks; Percent graduates accepted into desired graduate programs; Faculty credentials; Extra certifications available to students; Ranking; Availability of internship and practical experiences; Evidence of strong communication skills.

- 26. Life cycle cost is the sum of all recurring and one-time (non-recurring) costs over the full life span or a specified period of a good, service, structure, or system. In includes purchase price, installation cost, operating costs, maintenance and upgrade costs, and remaining (residual or salvage) value at the end of ownership or its useful life. See http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/life-cycle-cost.html#ixzz3HNVprayz.

- 27.http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/affordability.html#ixzz3HNUNwGXi

- 28. Enrico Moretti.

- 29.Gault B, Reichlin L, Roman S. College Affordability for Low-Income Adults: Improving Returns on Investment for Families and Society. http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/college-affordability-for-low-income-adults-improving-returns-on-investment-for-families-and-society/at_download/file.

- 30.Janke KK, Kelley KA, Kuba SE, et al. Re-envisioning assessment for the Academy and the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education’s standards revision process. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;77(7) doi: 10.5688/ajpe777141. Article 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Annual Report 2014. Available at https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/2014AnnualReport.pdf. Accessed on May 14, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. NAPLEX Passing Rates for 2012 and 2013 Graduates per Pharmacy School. https://www.nabp.net/system/rich/rich_files/rich_files/000/000/191/original/naplex-pass-rates-2013.pdf. Accessed on May 14, 2015.

- 33.Lingle EW, Jones CE, Clark KJ, et al. Consideration of pharmacy program quality indicators. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(5) Article 111. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelley KA, Demb A. Instrumentation for comparing student and faculty perceptions of competency-based assessment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7006134. Article 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jungnickel PW, Kelley KW, Hammer DP, et al. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8) doi: 10.5688/aj7308156. Article 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blouin RA, Riffee WH, Robinson ET, et al. Roles of innovation in education delivery. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8) doi: 10.5688/aj7308154. Article 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. Standards 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education https://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/StandardsRevision.asp)

- 38.Lucas KH, Testman JA, Hoyland MN, et al. Correlation between active learning coursework and student retention or core content during advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe778171. Article 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller BM, Moore DE, Stead WW, et al. Beyond Flexner: a new model for continuous learning in the health professions. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):266–272. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c859fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith KM, Scott DR, Barner JC, et al. Interprofessional education in six US colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4) doi: 10.5688/aj730461. Article 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Educational Outcomes. 2013. Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education. http://www.aacp.org/Documents/CAPEoutcomes071213.pdf.

- 42.Alsharif NZ. Knowledge, skills – and accountability? Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(9) doi: 10.5688/ajpe789159. Article 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross LA, Janke KK, Boyle CJ, et al. Preparation of faculty members and students to be citizen leaders and pharmacy advocates. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10) doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710220. Article 220. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lancaster JW, Stein SM, MacLean LG, et al. Faculty Development Program Models to Advance Teaching and Learning Within Health Science Programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(5) doi: 10.5688/ajpe78599. Article 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gleason BL, Siracuse MV, Moniri NH, et al. Evolution of preprofessional pharmacy curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(5) doi: 10.5688/ajpe77595. Article 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Medical Teacher. 2010;32:638–645. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cracking the Credit Hour: http://newamerica.net/publications/policy/cracking_the_credit_hour.

- 48. The Pharmacist Workforce: A Study of the Supply and Demand for Pharmacists. A Report of the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, December 2000. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/pharmaciststudy.pdf. Accessed on February 2, 2015.

- 49. Academic Pharmacy’s Vital Statistics. http://www.aacp.org/about/Pages/Vitalstats.aspx. Accessed on February 2, 2015.

- 50. The Role of a Pharmacist. http://www.aacp.org/resources/student/pharmacyforyou/Pages/roleofapharmacist.aspx. Accessed on February 2, 2015.

- 51.Murphy JE. The Visible Ingredient (Harvey A.K. Whitney Award lecture). http://www.harveywhitney.org/lectures.php?lecture=67. Accessed on February 17, 2015.

- 52.Anderson DC, Sheffield MC. Massey Hill A, Cobb HH. Influences on pharmacy students’ decision to pursue a doctor of pharmacy degree. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2) doi: 10.5688/aj720222. Article 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayes B. Increasing the representation of underrepresented minority groups in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1) doi: 10.5688/aj720114. Article 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boyce EG, Lawson LA. Preprofessional curriculum in preparation for doctor of pharmacy educational programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8) doi: 10.5688/aj7308155. Article 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeLander GE. Optimizing professional education in pharmacy: are the ingredients as important as the recipe? Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2) Article 35. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kirschenbaum HL. Preprofessional curriculum: is it time for another look? Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(8) doi: 10.5688/aj7408156. Article 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Broedel-Zaugg K, Buring SM, et al. Academic pharmacy administrators’ perceptions of core requirements for entry into professional pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3) doi: 10.5688/aj720352. Article 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vongvanith VV, Huntington SA, Nkansah NT. Diversity characteristics of the 2008-2009 pharmacy college application service applicant pool. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe768151. Article 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bridging the Higher Education Divide: Strengthening Community Colleges and Restoring the American Dream. A Report of the Century Foundation Task Force on Preventing Community Colleges from Becoming Separate and Unequal. http://tcf.org/assets/downloads/20130523-Bridging_the_Higher_Education_Divide-REPORT-ONLY.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2015.

- 60.Keshishian F, Brocavich JM, Boone T, Pal S. Motivating Factors Influencing College Students’ Choice of Academic Major. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3) doi: 10.5688/aj740346. Article 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powell H, Scott JA. Funding changes and their effect on ethnic minority student access. Focus on Colleges, Universities and Schools. 2013;7(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 62. US Department of Education. Federal Student Aid. https://studentaid.ed.gov/types/loans/subsidized-unsubsidized#eligibility. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- 63. Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions. A Report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/SullivanReport.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2015.

- 64.Winkleby MA, et al. Increasing diversity in science and health professions: a 21-year longitudinal study documenting college and career success. J Sci Educ Tech. 2009;18:535–545. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiggs JS, Elam CL. Recruitment and retention: the development of an action plan for African American health professions students. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92(3):125–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White C, Louis B, et al. Institutional strategies to achieve diversity and inclusion in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(5) doi: 10.5688/ajpe77597. Article 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Strengthening America’s Higher Education System: Republican Pirorities for Reauthorizing the Higher Education Act. House Committee on Education and Workforce. http://edworkforce.house.gov/uploadedfiles/hea_whitepaper.pdf. Accessed on April 29, 2015.

- 68. Alexander seeks input from higher education community on accreditation, risk-sharing and consumer information. US Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. http://www.help.senate.gov/newsroom/press/release/?id=4dc6f28c-e8ea-4a94-9c82-91db98e10c0d&groups=Chair. Accessed April 29, 2015.

- 69. White House higher education policy. https://www.whitehouse.gov/issues/education/higher-education. Accessed April 29, 2015.