Abstract

Directed neutrophil migration in blood vessels and tissues is critical for proper immune function; however, the mechanisms that regulate three-dimensional neutrophil chemotaxis remain unclear. It has been shown that integrins are dispensable for interstitial three-dimensional (3D) leukocyte migration; however, the role of integrin regulatory proteins during directed neutrophil migration is not known. Using a novel microfluidic gradient generator amenable to 2D and 3D analysis, we found that the integrin regulatory proteins Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 differentially regulate neutrophil polarization and directed migration to gradients of chemoattractant in 2D versus 3D. Both talin-1-deficient and RIAM-deficient neutrophil-like cells had impaired adhesion, polarization, and migration on 2D surfaces whereas in 3D the cells polarized but had impaired 3D chemotactic velocity. Kindlin-3 deficient cells were able to polarize and migrate on 2D surfaces but had impaired directionality. In a 3D environment, Kindlin-3 deficient cells displayed efficient chemotaxis. These findings demonstrate that the role of integrin regulatory proteins in cell polarity and directed migration can be different in 2D and 3D.

Keywords: Neutrophil, Chemotaxis, Integrin regulatory proteins, Microfluidics

1 Introduction

Integrins play an important role in many cellular processes including adhesion to the extracellular matrix, migration, leukocyte transmigration, and differentiation (Hynes 2002; Shattil et al. 2010; Huttenlocher and Horwitz 2011). Many human diseases including inherited immunodeficiency diseases and cancer have been associated with altered integrin function. Integrins are heterodimers comprised of an α subunit and a β subunit. Each subunit contains an ectodomain, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail. The integrin ectodomain transitions between three conformation states: a closed or bent conformation, an intermediate conformation, and an extended or open conformation (Nishida et al. 2006; Luo et al. 2007). Resting integrins exist in a bent conformation and exhibit low affinity for ligand-binding. In response to inside-out signaling, integrins can change their conformation to an intermediate or open high-affinity conformation (Luo et al. 2007). Integrin-ligand binding can also induce clustering of hetero-oligomers (Li et al. 2003) and the recruitment of protein complexes to their cytoplasmic tail. This mediates outside-in signaling, which is critical during cell polarization and migration (Wu 2004; Critchley and Gingras 2008; Wang et al. 2012).

The integrin regulatory proteins Kindlin-3, talin-1, and RIAM associate with the integrin cytoplasmic tail domain and regulate integrin affinity through inside-out signaling. Kindlin is a ~76 kDa FERM domain containing protein named after the gene mutated in Kindler syndrome, a skin blistering disease (Moser et al. 2009b). Kindlin-3 expression is restricted to hematopoietic cells (Ussar et al. 2006) and is essential for integrin activation. Loss of function Kindlin-3 mutations are found in patients with leukocyte-adhesion deficiency (LAD) type III, an immunodeficiency in which leukocyte recruitment is impaired (Moser et al. 2008; Svensson et al. 2009). Investigations into leukocyte adhesion under flow have revealed that the adhesion defect of Kindlin-3 deficient leukocytes is at the level of arrest, the transition from rolling to firm adhesion (Manevich-Mendelson et al. 2009; Moser et al. 2009a). Kindlin-3 binds to the NxxY motif in the cytoplasmic domain of β integrins through its FERM domain causing a conformational change in the integrin from the closed state to the open high-affinity state (Moser et al. 2008, 2009a, b; Shattil et al. 2010).

Talin-1 is a ~270 kDa protein that consists of a ~47 kDa head domain containing a FERM domain and a ~220 kDa C-terminal flexible rod domain that binds to vinculin and F-actin (Smith and McCann 2007; Moser et al. 2009b). Talin-1 is required for integrin adhesion (Tadokoro et al. 2003; Han et al. 2006). Talin-1 binds to the NPxY motif in the cytoplasmic domain of β integrins through its FERM domain, causing a conformational change in the ectodomain of the integrin that increases integrin affinity (Tadokoro et al. 2003; Moser et al. 2009b). Talin-1 is required for integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) extension, which shifts the integrin to the intermediate affinity conformation. Both talin-1 and Kindlin-3 are needed to induce the high affinity state of LFA-1 in neutrophils. These signaling roles suggest that talin-1 and Kindlin-3 act together during inside-out signaling to integrins (Moser et al. 2009b; Lefort et al. 2012). Talin-1 is also involved in outside-in signaling and functions as a bridge that links the ECM and the actin cytoskeleton, thereby enabling cells to exert tensile force on the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Critchley and Gingras 2008; Moser et al. 2009b; Wang et al. 2012).

RIAM is a ~73 kDa protein that interacts with the Rap1 GTPase (Lafuente et al. 2004). RIAM depletion impairs RAP1-dependent cell adhesion and RIAM over-expression induces lamellipodia formation, indicating that RIAM increases both integrin affinity and outside-in signaling (Lafuente et al. 2004; Han et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2008; Shattil et al. 2010). When cells are stimulated with thrombin or other extracellular stimuli, RIAM is recruited to the plasma membrane to interact with activated RAP1 (Lafuente et al. 2004; Shattil et al. 2010). RIAM then recruits talin-1 to the plasma membrane to form a RIAM/talin-1 complex, facilitating the interaction between the β integrin subunit and talin-1 (Han et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2008). Upon talin-1 interaction, the integrin shifts to the high-affinity state. During the outside-in signaling process, RIAM induces lamellipodia formation through its interaction with Profilin and VASP/ENA, which leads to actin polymerization and cell polarization (Lafuente et al. 2004).

Previous studies have largely focused on the role of integrins and integrin regulatory proteins in cell migration on 2D surfaces (Hynes 2002; Shattil et al. 2010; Huttenlocher and Horwitz 2011). However, recent studies suggest that integrins can be dispensable for 3D migration and that integrin-deficient leukocytes can migrate in 3D lattices using actin based forces (Lammermann et al. 2008). These reports raise questions as to the function of integrin regulatory proteins during leukocyte chemotaxis in 3D environments. The study of cell polarization and directed migration, however, is limited by the challenges of creating controllable gradients of soluble factors in 3D. While microfluidics has recently been an enabling tool in the development of research platforms for studying chemotaxis (Berthier et al. 2010; Cavnar et al. 2012; Sackmann et al. 2012), most platforms have been designed for migration on a 2D plastic surface. Studying protein localization and immunostaining of cells fixed in their migratory state in response to a gradient in 3D remains a technical challenge. Typically, the 3D matrix prevents the flow of fixing agent to the location of the cells and the diffusion distance alters the cells before they become fixed.

In this study, we developed new microfluidic tools that generate point-source gradients in microscale devices similar to those created by traditional needle assays. The devices also enable the visualization of cells migrating in a 3D matrix with high-resolution microscopy, and the flow of fixing agent in short diffusion distances from the location of the cells to allow the rapid delivery of factors. The structure of the microfluidic device was specifically designed to allow for the rapid delivery of factors to cells and enables the fixation of cells with washes in 3D which represents a significant advance over previous systems. We used this novel microfluidic platform to investigate the roles of Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 during chemoattractant induced cell polarization and directional migration of neutrophil-like cells in 3D and 2D. We found that there exist two distinct roles for these factors: enabling the proper cell polarization in a chemoattractant gradient and the directed migration within a 3D matrix. We found that Kindlin-3 does not have an effect on neutrophil motility but is required for facilitating directionality on a 2D surface but not in a 3D matrix. We also found that RIAM and talin-1 are required for adhesion and leading edge formation on 2D surfaces and facilitate directional motility in 3D matrigel.

2 Methods

2.1 Cell culture

PLB-985 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomyocin at a concentration of 0.1–1×106 cells/mL. To differentiate PLB-985 cells, 1.25 % DMSO was added to 1.3×105 cells/mL for 6 days. HEK293T cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomyocin.

2.2 Viral infections

Lentiviral Kindlin-3, RIAM, talin-1, and control shRNA targets were purchased (Santa Cruz and Open Biosystems). HEK293T cells were grown to 70 % confluency in a 10 cm tissue culture dish for each lentiviral target and were transfected with 6 µg of Kindlin-3, RIAM, Talin-1, or control shRNA, 0.6 µg of VSV-G, and 5.4 µg of CMV 8.91 by calcium phosphate method. 72 h after transfection, viral supernatant was collected and concentrated using a lentivirus concentrator (Lenti-X, Takara Bio Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. 1×106 PLB-985 cells were infected with viral supernatant for 3 days in the presence of 15 µg polybrene as previously described (Cavnar et al. 2012). Stable cell lines were generated with 1 µg /mL puromycin selection.

2.3 Immunoblotting

Differentiated PLB-985 cells were placed in lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl2, 1 % Nonidet P-40, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10 % glycerol, 1 µg/mL pepstatin A, 2 µg/mL aprotinin, 1 µg/mL leupeptin, and 200 nM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 % protease inhibitor mixture 2) on ice for 10 min and clarified by centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunoblotting of cell lysates was performed and blots were imaged with an infrared imaging system (Odyssey; LI-COR Biosciences). Anti-Kindlin-3 antibody (SIGMA, sab4200013), anti-RIAM antibody (Epitomics, ab92537), anti-talin-1 antibody (SIGMA, T3287), and anti-vinculin (SIGMA, clone VIN-11-5) were used as primary antibodies. Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 680 and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 800 (Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies.

2.4 Transwell chemotaxis assay

Transwell assays were performed as previously described (Cavnar et al. 2012). Briefly, transwell filters (3-µm pore size; Corning) were coated with 10 µg/mL fibrinogen (Sigma-Aldrich). 2×105 differentiated PLB-985 cells were plated in the top chamber and the number of cells migrating to 10 nM f-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) (Sigma-Aldrich) was determined after 90 min by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells transmigrated relative to loading control was determined and graphed as percent migrated relative to control shRNA + fMLP from at least three independent experiments.

2.5 Adhesion assay

Adhesion assays were performed as previously described (Cavnar et al. 2012). 1×105 control, Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 shRNA cells were labeled with calcein AM (Invitrogen) and plated in the presence or absence of 100 nM fMLP for 30 min in quadruplicate in a 96-well black microplate (Greiner Bio-one) coated with fibrinogen followed by blocking with 2 % BSA at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. Fluorescence was measured using a plate reader (Victor3 V; PerkinElmer). Plates were gently washed with mHBSS (HBSS, 20 mM HEPES, 0.1 % Human serum albumin) in between readings until the remaining control shRNA –fMLP cells were <10 % of the original input. Human serum albumin was obtained from American Red Cross Blood Services.

2.6 Microfluidic chemotaxis assays

Microfluidic devices were fabricated as previously described (Berthier et al. 2010; Cavnar et al. 2012). Microfluidic chambers were prepared by oxygen plasma treatment within the hours preceding the migration assay. Following the treatment and for 2D migration assays, the microfluidic chambers were coated with 10 µg/mL fibrinogen in PBS for 1 h at 37 °C. For 3D migration assays, cells were suspended in a polymerizable 3D matrigel matrix by mixing 40 µL ofmatrigel solution (BD, 356234) with 40 µL of mHBSS media and 40 µL of neutrophil suspension at a concentration of 12×106 cells/mL. Excess matrigel was removed by applying a gentle vacuum on the loading port to empty the channel on the outer edge of the migration area and allow the insertion of reagents, stains, and fixative solutions. The cell-matrigel mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, and flipped every 2 min to prevent cell settling until the gel was solidified.

To induce chemotaxis, a 3 µL of a solution of 1 µM fMLP in mHBSS media was added to the device. The fMLP gradient was allowed to set up and equilibrate in a 37 °C humidified chamber for 15 min before imaging. Time-lapse imaging was performed on multiple location simultaneously using a 10× objective and a motorized stage (Ludl Electronic Products) on an inverted microscope (Eclipse TE300) and the image acquisition software Metamorph (Molecular Devices). Images were taken every 30 s for 30 min with two locations in up to three devices being imaged simultaneously. Automated tracking algorithms were developed to display cell tracks of all analyzed cells and to measure chemotactic velocity (Berthier et al. 2010). Chemotaxis velocity was calculated as previously reported (Sackmann et al. 2012) using the following equation where n is the number of frames of time-lapse images, ΔT is the time interval between the first and last frame of the time-lapse, and δxi is the displacement along the axis of the gradient.

It describes the directional velocity toward the formation of a chemotactic gradient. The chemotactic index was calculated using the following equation.

2.7 Immunostaining

Cells were allowed to chemotax in the microfluidic devices for 30 min and fixed with 3.7 % paraformaldehyde in PHEM buffer. Fixed cells were blocked with 10 % goat serum in PHEM buffer and stained with FITC conjugated anti-β-tubulin, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich), and Rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 1 h. All samples were observed under a confocal microscope using 60x, zoom 1.6 (Olympus XI-70).

2.8 Statistical analysis

All data were evaluated by Student’s t test. p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Chemotaxis in 2D and 3D

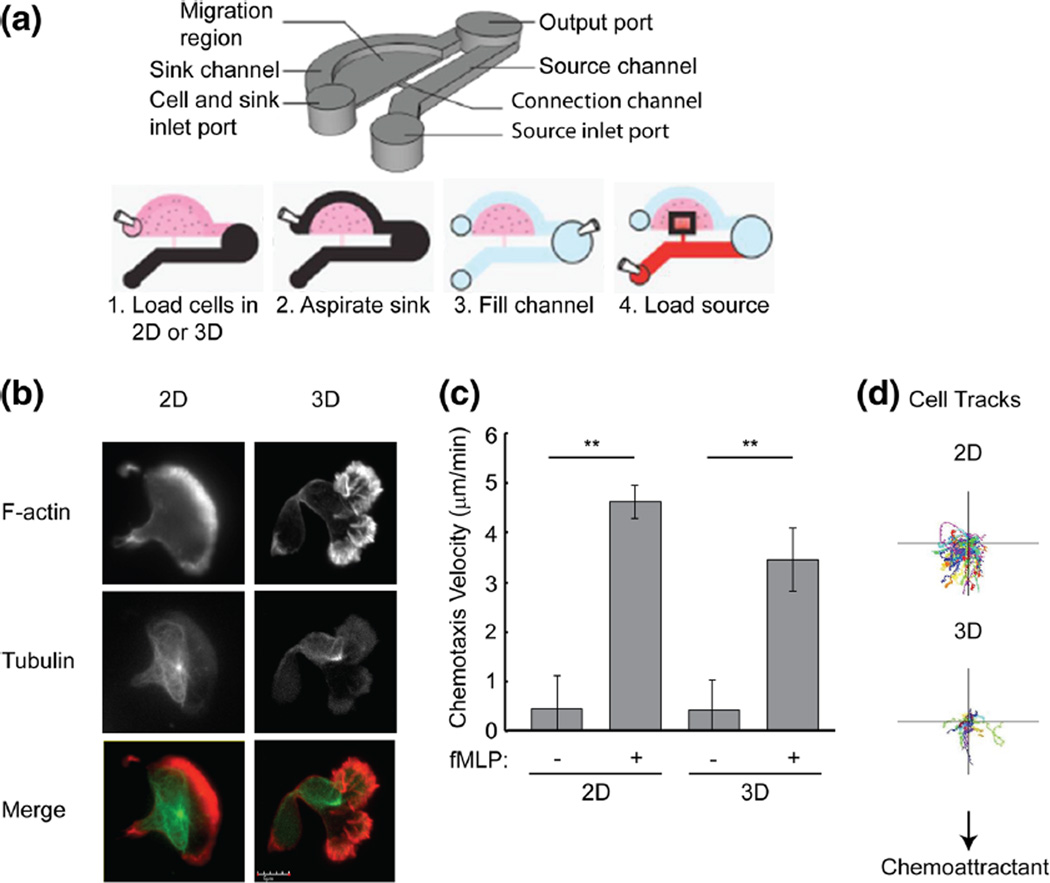

We developed a novel microfluidic device to study neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis in both 2D and 3D that is amenable to imaging migrating cells as well as fixing and staining cells in their migratory state. The microfluidic device is based on a user-friendly technology that allows the generation of a chemical gradient in a passive way with simple micro-pipettes and does not require specialized equipment such as syringe pumps. The microscale device can be easily loaded in a biosafety hood, placed in an incubator, and imaged on a microscope stage. This device is amenable to creating a gradient in a liquid (2D) environment and hydrogel (3D) environment and allows for imaging at high resolution (up to 60× objective) which enables quantitative analysis of the chemotaxis velocity (Fig. 1a) (Berthier et al. 2010; Cavnar et al. 2012; Sackmann et al. 2012). Importantly, the platform enables the fixing and staining of cells in their migratory state to study protein localization during the gradient sensing process. This device enables the fixation of cells with washes in three-dimensions, a significant advance over prior designs. To our knowledge, this is the first microfluidic device that allows the fixation of migrating neutrophils while chemotaxing in a 3D matrix.

Fig. 1.

Neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis in 2D and 3D. a Schematic of the microfluidic device used to analyze neutrophil chemotaxis. To perform 2D migration, the channel was coated with fibrinogen (10 µg/ml) before loading the cells. To perform 3D migration assay, the channel was filled with 20 µL of cell suspension mixed with 3D matrigel. b Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin (red) and tubulin (green) in control cells during chemotaxis to fMLP on 2D fibrinogen and in 3D matrigel. Scale bar, 5 µm. c Quantification of chemotaxis velocity of control cells during chemotaxis to fMLP d Automated cell tracking of control cells during chemotaxis to fMLP. Error bars represent mean±S.D., n=3, **, p<0.01 by student’s t test

To examine cell morphology during neutrophil chemotaxis on 2D surfaces and in 3D matrigel, differentiated PLB-985 neutrophil-like cells were fixed 30 min after fMLP stimulation and were stained for F-actin and tubulin. On the 2D surface, control cells displayed a typical polarized cell morphology with a single broad leading edge containing F-actin and a uropod (Fig. 1b) (Niggli 2003). In the 3D matrigel, cells showed multiple leading edge pseudopods that were enriched with F-actin (Fig. 1b).

Automated cell tracking algorithms were used to monitor directional migration toward the chemoattractant source (Berthier et al. 2010). Cell tracking analysis of fMLP stimulated cells demonstrated directed migration towards fMLP in both two- and three-dimensions (Fig. 1c). When compared with non-stimulated cells, the chemotaxis velocity was increased in fMLP stimulated cells on both 2D surfaces and in 3D matrigel (Fig. 1c and d). These results demonstrate a novel microfluidic system for the efficient analysis of 2D and 3D directed polarization and migration.

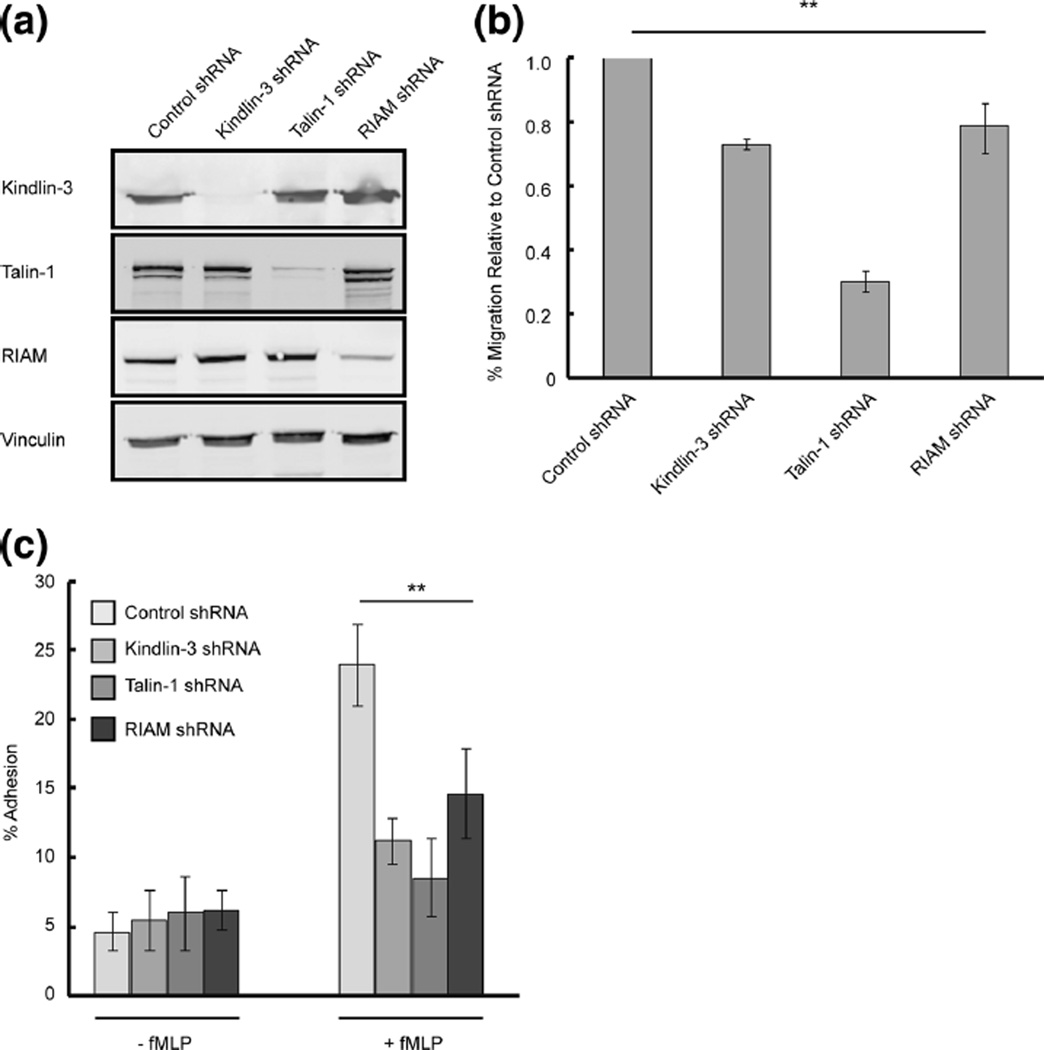

3.2 The role of Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 in transwell migration and adhesion

To characterize the role of integrin regulatory proteins during neutrophil migration, Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1-deficient PLB-985 cells were generated using lentiviral delivered shRNA. The knockdown of the target protein did not affect the expression level of the other integrin regulatory proteins (Fig. 2a). Using a transwell assay to investigate chemotaxis to fMLP, we found that Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 knockdown cells had impaired migration, compared with control cells (Fig. 2b). To determine if the defects in migration were due to altered adhesion, adhesion assays on fibrinogen were performed. Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 knockdown cells showed defects in fMLP-induced neutrophil adhesion compared to control cells (Fig. 2c). These findings support previous reports that Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 are essential for efficient neutrophil adhesion and chemotaxis in response to fMLP in 2D (Moser et al. 2009a; Worth et al. 2010; Hyduk et al. 2011).

Fig. 2.

Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 are required for cell adhesion and chemotaxis. a Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 knockdown cell lines were generated by transducing lentiviral shRNA targets in PLB-985 cells. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Vinculin was used as a loading control. b Transwell assay of Kindlin-3, RIAM, talin-1, and control shRNA cell lines plated on fibrinogen (10 µg/ml). Cell migration was quantified by flow cytometry and graphed as percent migrated relative to control shRNA +fMLP. Error bars represent mean±S.D., n=3, **, p<0.01 by student’s t test. c Adhesion assay of differentiated Kindlin-3, RIAM, talin-1, and control shRNA cell lines plated on fibrinogen (10 µg/ml). Cells were graphed as a percentage of input. Error bars represent mean±S.D., n=3, **, p<0.01 by student’s t test

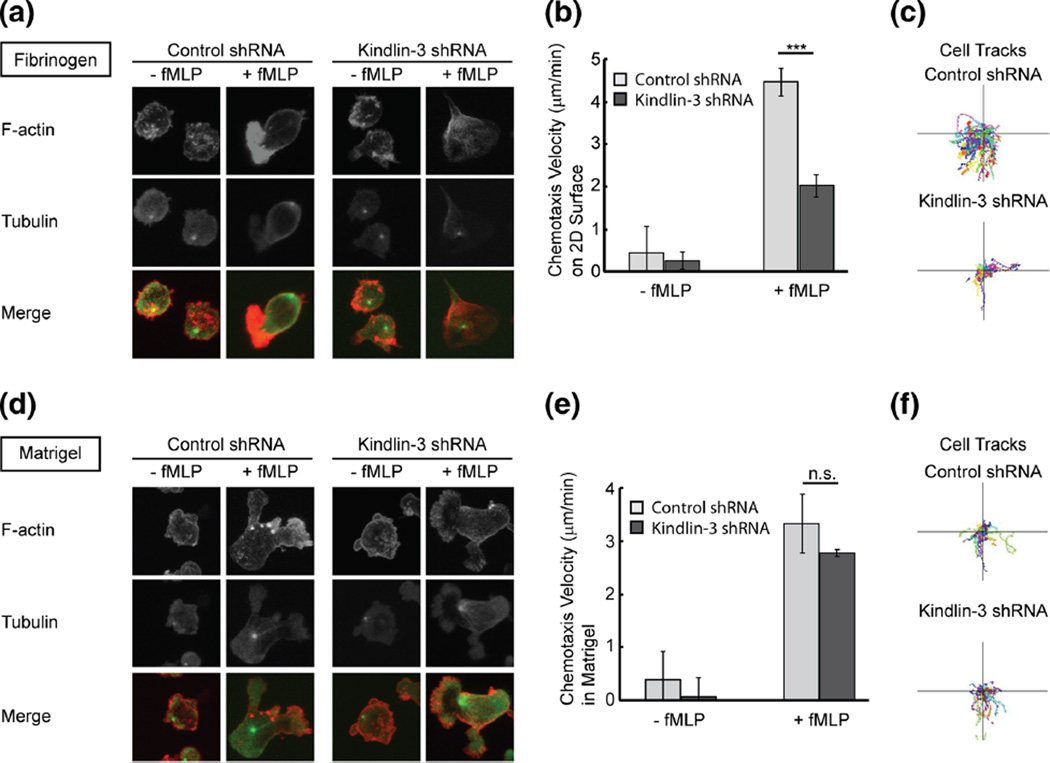

3.3 The role of Kindlin-3 during neutrophil polarization and directed migration in 2D and 3D

Transwell assays do not allow for the quantification of characteristic values of migration such as the chemotaxis index, velocity, and cell polarization. Transwell membranes also do not model 3D migration. We therefore used microfluidic devices to investigate the role of Kindlin-3 during directional migration and cell polarization in 2D and 3D. On a 2D surface, Kindlin-3-deficient cells polarized normally; however, the leading edge appeared to be less enriched with F-actin compared to control cells (Fig. 3a). The migration tracks of Kindlin-3 knockdown cells showed impaired directed migration to fMLP (Fig. 3c). To further quantify the effect of Kindlin-3 depletion on directional migration, the chemotaxis velocity was measured using automated cell tracking algorithms. Kindlin-3 knockdown decreased the fMLP-induced chemotaxis velocity in 2D (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Neutrophil polarization and directed migration of Kindlin-3-deficient cells in 2D and 3D. a Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin (red) and tubulin (green) in control and Kindlin-3 knockdown cells on a fibrinogen coated surface in the presence or absence of fMLP (1 µM). b Quantification of chemotaxis velocity of control and Kindlin-3 knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP on 2D fibrinogen. Error bars represent mean±S.D., n=3, ***, p<0.001 by student’s t test. c Automated cell tracking of control and Kindlin-3 knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP on 2D fibrinogen. d Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin (red) and tubulin (green) in control and Kindlin-3 knockdown cells in 3D matrigel in the presence or absence of fMLP (1 µM). e Quantification of chemotaxis velocity of control and Kindlin-3 knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP in 3D matrigel. Error bars represent mean±S.D., n=3, student’s t test. f Automated cell tracking of control and Kindlin-3 knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP in 3D matrigel

In 3D matrigel Kindlin-3 knockdown did not affect cell polarization or actin staining, and like control cells, Kindlin-3 deficient cells displayed multiple pseudopods (Fig. 3d). In contrast to 2D migration, Kindlin-3 depletion did not affect fMLP-induced chemotaxis velocity in 3D matrigel when compared to control cells (Fig. 3e and f). Taken together, the findings indicate that Kindlin-3 is required for facilitating directionality on 2D surfaces but not in 3D matrigel during neutrophil chemotaxis.

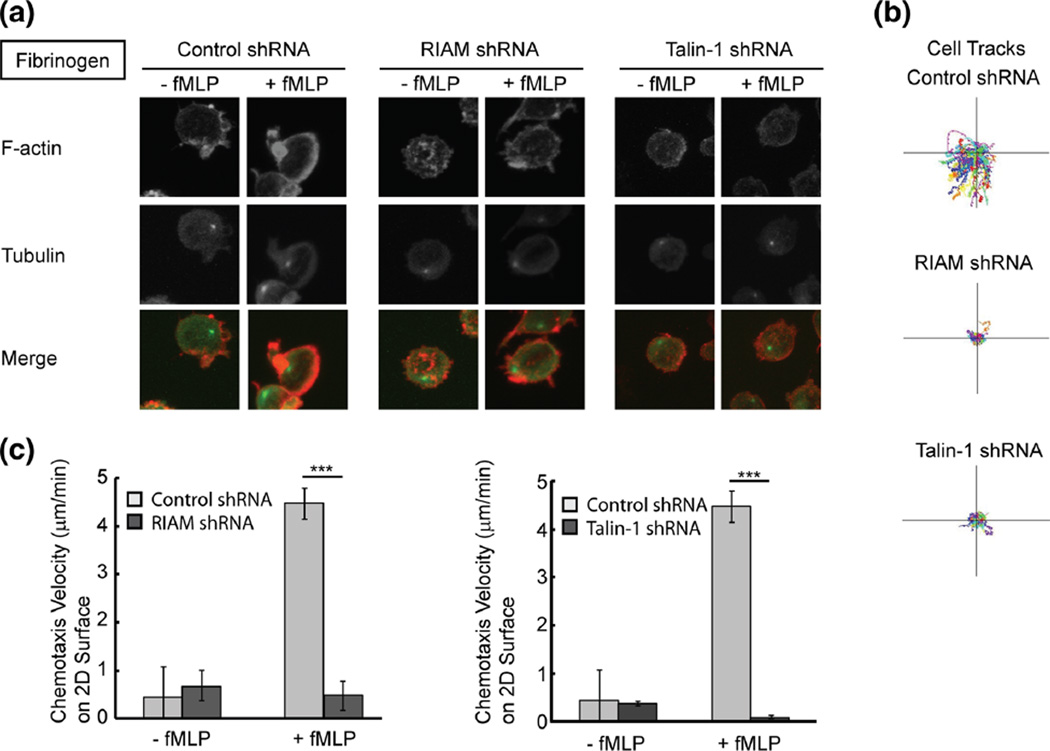

3.4 The role of RIAM and talin-1 during neutrophil polarization and directed migration in 2D and 3D

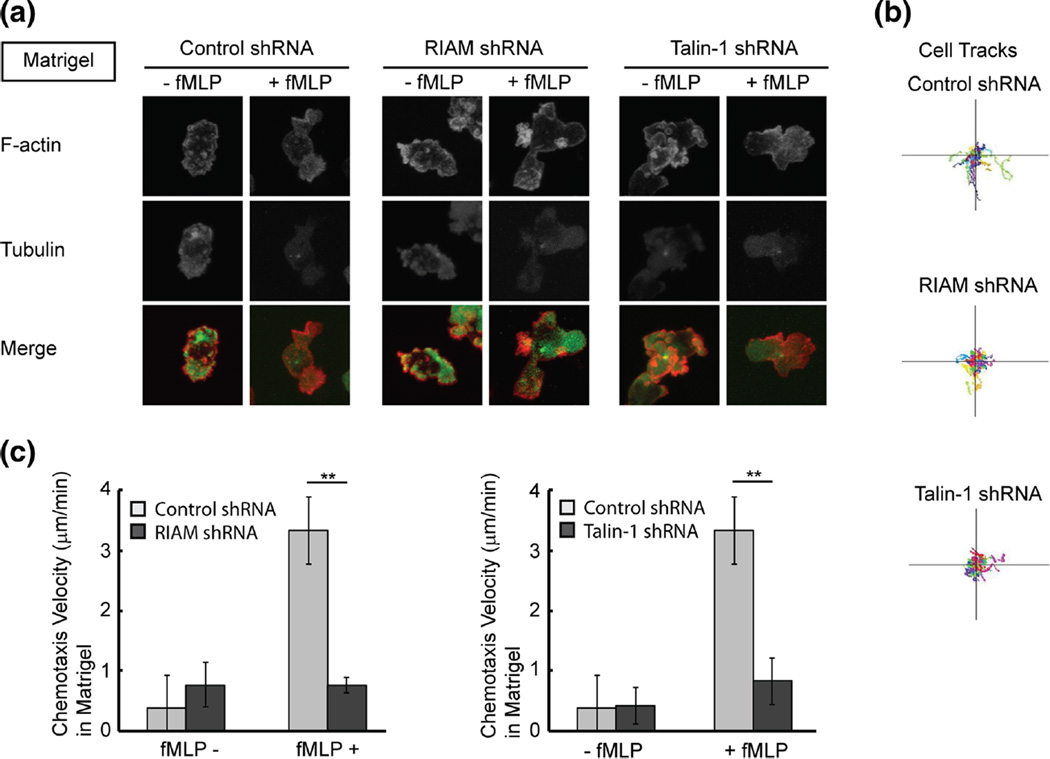

It is known that RIAM activates talin-1 during integrin activation (Han et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2008), therefore, microfluidic devices were used to examine the role of RIAM and talin-1 in directional migration and polarization of neutrophil-like cells on 2D surfaces and in 3D matrigel. On 2D surfaces, RIAM knockdown cells showed a polarization defect, in which cells did not have a clearly defined leading edge (Fig. 4a). Similar to the RIAM-deficient cells, talin-1-deficient cells also had impaired polarization (Fig. 4a). Both RIAM-deficient cells and talin-1-deficient cells showed impaired directionality towards the chemoattractant fMLP with decreased migration tracks and chemotaxis velocity compared to control cells (Fig. 4b and c). In 3D matrigel, both RIAM knockdown cells and talin-1 knockdown cells generally showed a single protrusion, in contrast to the multiple protrusions seen in control cells (Fig. 5a). RIAM-deficient and talin-1-deficient cells also had impaired chemotaxis velocity in 3D matrigel (Fig. 5b and c). The findings indicate that RIAMand talin-1 are both required for leading edge formation on 2D surfaces and mediate pseudopod formation and directionality during chemotaxis in 3D matrigel.

Fig. 4.

Neutrophil polarization and directedmigration of RIAM-deficient cells in 2D. a Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin (red) and tubulin (green) in control, RIAM knockdown cells, and talin-1 knockdown cells on 2D fibrinogen in the presence or absence of fMLP (1 µM). b Automated cell tracking of control, RIAM knockdown, and talin-1 knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP on 2D fibrinogen. c Quantification of chemotaxis velocity of control and RIAM knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP on 2D fibrinogen. Error bars represent mean±S.D., n=3, ***, p<0.001 by student’s t test

Fig. 5.

Neutrophil polarization and directedmigration of RIAM-deficient cells in 3D. a Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin (red) and tubulin (green) in control, RIAM knockdown cells, and talin-1 knockdown cells in 3D matrigel in the presence or absence of fMLP (1 µM). b Automated cell tracking of control, RIAM knockdown cells, and talin-1 knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP in 3D matrigel. c Quantification of chemotaxis velocity of control, RIAM knockdown, and talin-1 knockdown cells during chemotaxis to fMLP in 3D matrigel. Error bars represent mean±S.D., n=3, **, p<0.01 by student’s t test

4 Discussion

In this study, we characterized the different roles of integrin regulatory proteins in 2D and 3D directed migration. We found that the integrin regulatory protein Kindlin-3 is dispensable for 3D chemotaxis, while both talin-1 and RIAM are required for efficient 3D chemotaxis. This is in contrast to 2D where the regulatory proteins, talin-1, RIAM, and Kindlin-3, are all important for adhesion and directed migration, although the effects of talin-1 and RIAM depletion are more significant. These findings highlight the importance of understanding how migration is differentially regulated in 3D and suggest that there is likely more redundancy in the mechanisms that facilitate 3D motility.

Previous reports have shown that Kindlin-3, RIAM, and talin-1 are essential for neutrophil chemotaxis on 2D surfaces, likely because of their role in integrin activation (Moser et al. 2009a; Worth et al. 2010; Hyduk et al. 2011). Two-dimensional attachment and motility in vitro is analogous to the movement of leukocytes along blood vessels in vivo, in which Kindlin-3, RIAM and talin-1 have all been implicated. However, their specific contribution to neutrophil chemotaxis has not previously been well characterized. Based on our findings that Kindlin-3 is required for directionality and that RIAM and talin-1 are required for leading edge formation, the results suggest that Kindlin-3 works in parallel with RIAM and talin-1. There is substantial recent evidence to support this idea in the literature. Kindlin-3 has been reported to be required for resistance against cell detachment and it is required for regulating integrin affinity (Hyduk et al. 2011; Vestweber 2012). Conversely, talin-1 and RIAM are required for cell spreading, supporting the idea that they play a role in both inside-out and outside-in signaling to modulate cell adhesion and motility on 2D surfaces (Han et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2008). Therefore, we speculate that Kindlin-3 acts through inside-out signaling to facilitate directionality, while RIAM and talin-1 also enable outside-in signaling to induce leading edge formation on 2D surfaces.

The contribution of integrins during leukocyte chemotaxis in 3D environments remains poorly understood. It has been recently reported that integrin-deficient leukocytes migrate directionally in 3D collagen gels. These results suggest that integrin regulatory proteins could have functions other than cell adhesion during 3D migration (Lammermann et al. 2008). Our finding that RIAM and talin-1 are required for directionality in 3D matrigel may provide clues as to their roles in 3D migration. It has been reported that the directional migration of leukocytes in a 3D collagen environment depends on protrusive flowing of the leading edge (Lammermann et al. 2008); we have shown that RIAM and talin-1 knockdown cells form a single protrusion, unlike control cells that form multiple protrusions in 3D matrigel. We, therefore, speculate that RIAM and talin-1 knockdown cells have impaired directionality because the cells have protrusion formation defects. RIAM has been reported to facilitate actin polymerization through its interaction with Profilin and VASP/ENA, and talin-1 has been reported to interact with Tiam1, a Rac GEF, to activate Rac1, thereby facilitating leading edge formation (Lafuente et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2012). Therefore, we speculate that these integrin regulatory proteins are regulating directionality during neutrophil chemotaxis in 3D environments by facilitating protrusion formation.

In summary, these findings highlight the importance of analyzing 3D migration to understand how specific pathways may impact different types of in vivo migration such as interstitial motility and the migration of leukocytes along endothelial surfaces. We have found an essential role for the integrin regulatory proteins, talin-1, Kindlin-3, and RIAM during 2D adhesion with distinct roles in cell polarization and protrusion formation. In contrast, Kindlin-3, like leukocyte integrins, seems to be dispensable for leukocyte directed migration in 3D, supporting the idea that there may be redundancy in the mechanisms that modulate 3D movement. However it is also possible that increased availability of ligand binding sites in 3D may contribute to the differential contribution of Kindlin-3 to 2D and 3D motility (Cohen et al. 2013). We have also found that RIAM and talin-1 play essential roles in regulating the efficiency of 3D chemotaxis, suggesting that RIAM and talin-1 may contribute to 3D motility through mechanisms other than the direct regulation of integrin affinity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1EB010039 (to A. H. and D. J. B.), AHA Grant 10POST3230031 (to P. J. C.), and University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Cancer Center, Support Grant P30 CA014520 (to D.J.B).

Disclosures David J. Beebe holds equity in Bellbrook Labs, LLC, Tasso, Inc., and Salus Discovery, LLC. E. Berthier holds equity in Salus Discovery, LLC and Tasso, Inc. P. Cavnar holds equity in Salus Discovery, LLC.

Footnotes

Author contributions YY, PC, EB, DB and AH designed the studies, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. YY, DAB, PC, EB performed experiments and analyzed data.

References

- Berthier E, Surfus J, et al. An arrayed high-content chemotaxis assay for patient diagnosis. Integr Biol (Camb) 2010;2(11–12):630–638. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00030b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavnar PJ, Mogen K, et al. The actin regulatory protein HS1 interacts with Arp2/3 and mediates efficient neutrophil chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(30):25466–25477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.364562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SJ, Gurevich I, et al. The integrin coactivator Kindlin-3 is not required for lymphocyte diapedesis. Blood. 2013;122(15):2609–2617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley DR, Gingras AR. Talin at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 9):1345–1347. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lim CJ, et al. Reconstructing and deconstructing agonist-induced activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Curr Biol. 2006;16(18):1796–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher A, Horwitz AR. Integrins in cell migration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(9):a005074. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyduk SJ, Rullo J, et al. Talin-1 and kindlin-3 regulate alpha4beta1 integrin-mediated adhesion stabilization, but not G protein-coupled receptor-induced affinity upregulation. J Immunol. 2011;187(8):4360–4368. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110(6):673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente EM, van Puijenbroek AA, et al. RIAM, an Ena/VASP and profilin ligand, interacts with Rap1-GTP and mediates Rap1-induced adhesion. Dev Cell. 2004;7(4):585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammermann T, Bader BL, et al. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature. 2008;453(7191):51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefort CT, Rossaint J, et al. Distinct roles for talin-1 and kindlin-3 in LFA-1 extension and affinity regulation. Blood. 2012;119(18):4275–4282. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Mitra N, et al. Activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 by modulation of transmembrane helix associations. Science. 2003;300(5620):795–798. doi: 10.1126/science.1079441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo BH, Carman CV, et al. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manevich-Mendelson E, Feigelson SW, et al. Loss of Kindlin-3 in LAD-III eliminates LFA-1 but not VLA-4 adhesiveness developed under shear flow conditions. Blood. 2009;114(11):2344–2353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-218636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M, Nieswandt B, et al. Kindlin-3 is essential for integrin activation and platelet aggregation. Nat Med. 2008;14(3):325–330. doi: 10.1038/nm1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M, Bauer M, et al. Kindlin-3 is required for beta2 integrin-mediated leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. Nat Med. 2009a;15(3):300–305. doi: 10.1038/nm.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M, Legate KR, et al. The tail of integrins, talin, and kindlins. Science. 2009b;324(5929):895–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1163865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niggli V. Microtubule-disruption-induced and chemotactic-peptide-induced migration of human neutrophils: implications for differential sets of signalling pathways. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 5):813–822. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida N, Xie C, et al. Activation of leukocyte beta2 integrins by conversion from bent to extended conformations. Immunity. 2006;25(4):583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackmann EK, Berthier E, et al. Microfluidic kit-on-a-lid: a versatile platform for neutrophil chemotaxis assays. Blood. 2012;120(14):e45–e53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil SJ, Kim C, et al. The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(4):288–300. doi: 10.1038/nrm2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SJ, McCann RO. A C-terminal dimerizationmotif is required for focal adhesion targeting of Talin1 and the interaction of the Talin1 I/LWEQ module with F-actin. Biochemistry. 2007;46(38):10886–10898. doi: 10.1021/bi700637a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L, Howarth K, et al. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency-III is caused by mutations in KINDLIN3 affecting integrin activation. Nat Med. 2009;15(3):306–312. doi: 10.1038/nm.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, et al. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 2003;302(5642):103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussar S, Wang HV, et al. The Kindlins: subcellular localization and expression during murine development. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(16):3142–3151. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestweber D. Novel insights into leukocyte extravasation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19(3):212–217. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283523e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Watanabe T, et al. Tiam1 interaction with the PAR complex promotes talin-mediated Rac1 activation during polarized cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2012;199(2):331–345. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201202041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Bodin L, et al. Mechanisms and consequences of agonist-induced talin recruitment to platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3. J Cell Biol. 2008;181(7):1211–1222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worth DC, Hodivala-Dilke K, et al. Alpha v beta3 integrin spatially regulates VASP and RIAM to control adhesion dynamics and migration. J Cell Biol. 2010;189(2):369–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. The PINCH-ILK-parvin complexes: assembly, functions and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1692(2–3):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]