Abstract

Development of probes that can discriminate G-quadruplex (GQ) structures and indentify efficient GQ binders on the basis of topology and nucleic acid type is highly desired to advance GQ-directed therapeutic strategies. In this context, we describe the development of minimally perturbing and environment-sensitive pyrimidine nucleoside analogues, based on a 5-(benzofuran-2-yl)uracil core, as topology-specific fluorescence turn-on probes for human telomeric DNA and RNA GQs. The pyrimidine residues of one of the loop regions (TTA) of telomeric DNA and RNA GQ oligonucleotide (ON) sequences were replaced with 5-benzofuran-modified 2′-deoxyuridine and uridine analogues. Depending on the position of modification the fluorescent nucleoside analogues distinguish antiparallel, mixed parallel-antiparallel and parallel stranded DNA and RNA GQ topologies from corresponding duplexes with significant enhancement in fluorescence intensity and quantum yield. Further, these GQ sensors enabled the development of a simple fluorescence binding assay to quantify topology- and nucleic acid-specific binding of small molecule ligands to GQ structures. Together, our results demonstrate that these nucleoside analogues are useful GQ probes, which are anticipated to provide new opportunities to study and discover efficient G-quadruplex binders of therapeutic potential.

INTRODUCTION

Guanine-rich sequences with the potential to form non-canonical four-stranded nucleic acid structures called G-quadruplexes (GQs) have received particular attention in recent years due to their interesting structural features and biological functions (1,2). These sequences are abundantly found in human genome, particularly in telomeric DNA repeats and certain oncogenic promoter regions, and in untranslated regions of mRNA and telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) (3). Compelling evidence suggests that these structures play important roles in chromosome maintenance and transcriptional- and translational-control of proliferation-associated genes (e.g. c-myc, c-kit, NRAS, etc.) (4–6). In terms of structure, GQs exhibit a variety of folding topologies in vitro, which depend on the sequence and monovalent cations (7–9). For example, human telomeric (h-Telo) DNA repeats (TTAGGG)n typically form antiparallel and mixed parallel-antiparallel stranded intramolecular GQ structures in the presence of Na+ and K+ ions, respectively (10–13). However, equivalent RNA sequences form parallel GQ irrespective of Na+ and K+ ionic conditions (14,15).

Owing to the structural diversity of GQs and their role in disease states, G-rich sequences are being rigorously evaluated as novel therapeutic targets for cancer chemotherapy (1–6). This has led to a flurry of efforts in the development and therapeutic use of small molecule binders, which induce or stabilize GQ structures and modulate their biological function (16–27). Recent visualization of DNA and RNA GQ structures in cells has further bolstered the interest in this direction (28–34). Although many of these small molecules bind to GQs strongly, they still lack the required selectivity to differentiate different GQ topologies and nucleic acid type to progress to clinical trials. Furthermore, paucity of efficient chemical probes that can detect different GQ topologies and quantitatively report ligand binding has been a major impediment in the advancement of GQ-directed therapeutic strategies (35–37). These shortcomings are also evident as no GQ-binding ligand, except for quarfloxin, has been tested in clinical trials (38).

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) approach has been widely applied to study the formation, stability and dynamics of various GQ structures (39–41). In this approach, an appropriate FRET pair is covalently attached at the 5′ and 3′ ends of GQ forming oligonucleotide (ON) sequences and change in fluorescence upon folding in the presence of metal ions, complementary ONs or ligands is used as a measure to study various GQ structures (39–43). Such fluorescently-tagged GQs and aptamers based on GQ structures (e.g. thrombin binding aptamer) have also been elegantly utilized in the fluorometric detection of metal ions (44–46), proteins (47–49) and in screening assays to identify quadruplex ligands (50,51). In a different approach, the efficient excimer emission from pyrene-conjugated thrombin binding DNA aptamer enabled the sensitive detection of K+ ions (52). Interestingly, studies using differentially end-labeled GQ ONs, which exhibit quenching in fluorescence due to proximal ligand binding, revealed that GQ ligands bind to a GQ structure at distinct G-tetrads with varied binding affinities (53). The observed differences in binding affinities have been ascribed to the differences in physicochemical environment of G-tetrads of a GQ structure, and hence, such labeled GQ ONs have been predicted to serve as probes to indentify G-tetrad-specific ligands.

Ligands and metal complexes that show changes in their fluorescence upon binding to GQs have also been utilized as tools to detect and study the recognition properties of GQs (35–37,54–57). Alternatively, fluorescent purine surrogates (e.g. 6-methylisoxanthopterin and 2-aminopurine) and base-modified 2′-deoxyguanosine analogues containing vinyl, styryl, aryl or heteroaryl group have been incorporated into ONs and utilized in the study of DNA GQs (58–67). However, many of the fluorescent non-covalent binders and nucleoside analogues are structurally perturbing or poorly discriminate different GQ topologies or exhibit unfavourable photophysical properties (e.g. very low fluorescence due quenching by guanosine and emission in the UV region), which depend on the sequence and hence, hamper their implementation in discovery assays to indentify GQ binders (35,68). For example, 2-aminopurine (2AP), a fluorescent adenine analogue, has been incorporated into the loop region (TTA) of h-Telo DNA repeat and used as a structure-selective probe for DNA GQs and ligand binding (60,61). In an analogous study, 2AP and 6MI were incorporated into the loop positions of thrombin binding aptamer. Though these fluorescent analogues exhibited substantial enhancement in fluorescence intensity, which depended on the location of the analogues, they significantly destabilized the quadruplexes (66). Moreover, their ability to discriminate between DNA and RNA GQs and quantitatively report topology-specific binding of ligands to DNA and RNA GQs has not been explored. Therefore, it is envisioned that the therapeutic evaluation of GQs will greatly benefit from the development of fluorescence-based biophysical tools that (i) can specifically sense the formation of GQs with enhancement in fluorescence intensity, (ii) can distinguish different GQs based on topology and nucleic acid type, and (iii) are compatible to screening formats for the identification of small molecules that selectively bind to DNA and RNA GQs.

Here, we describe examples of minimally perturbing environment-sensitive fluorescent pyrimidine nucleoside analogues, based on a 5-(benzofuran-2-yl)uracil core, which when incorporated into one of the loop regions of human telomeric DNA and RNA ON sequences, clearly signal the formation of different DNA and RNA GQ structures with significant enhancement in fluorescence intensity. These emissive nucleosides selectively detect GQ structures from corresponding duplexes, and distinguish GQ topologies based on (i) ionic conditions (Na+ versus K+) and (ii) nucleic acid type (DNA vs. RNA). Furthermore, we utilized the conformation-sensitivity of the probes in developing a fluorescence binding assay to quantitatively determine topology-specific binding of ligands to DNA and RNA GQs. Our results demonstrate that these simple GQ sensors could provide an alternative platform for the development of screening assays to identify topology- and nucleic acid-specific GQ binders of therapeutic potential.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Photophysical analysis of fluorescently modified DNA and RNA GQs and corresponding duplexes

Steady-state fluorescence

GQ forming ONs 5/6/9/11 (0.25 μM) were heated at 90°C for 3 min in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing either 100 mM KCl or 100 mM NaCl. Samples were then cooled slowly to RT and were kept at 4°C for 1 h. Duplexes (0.25 μM) of ONs 5/6/9 were assembled by heating a 1:1 mixture of the ON with complementary DNA ON 8 in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing either 100 mM KCl or 100 mM NaCl at 90°C for 3 min. Duplexes (5•8, 6•8 and 9•8) were then cooled slowly to RT and stored at 4°C for 1 h. Fluorescently modified GQs and duplexes were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 8 and 10 nm, respectively. All fluorescence experiments were performed in triplicate in a micro fluorescence cuvette (Hellma, path length 1.0 cm) on a Horiba Jobin Yvon, Fluorolog-3 at 20°C.

Quantum yield determination

Quantum yield of fluorescently modified DNA and RNA ONs were determined relative to the quantum yield of nucleosides 1 and 2, respectively, by using the following equation (69).

|

where s is respective fluorescent nucleoside, x is fluorescently modified DNA and RNA ON constructs, A is the absorbance at excitation wavelength, F is the area under the emission curve, n is the refractive index of the buffer, and  is the quantum yield. Quantum yield of nucleosides 1 and 2 is 0.19 and 0.21, respectively.

is the quantum yield. Quantum yield of nucleosides 1 and 2 is 0.19 and 0.21, respectively.

Time-resolved fluorescence

Excited-state lifetime of GQs and duplexes (1 μM), assembled as mentioned above, were determined using TCSPC instrument (Horiba Jobin Yvon, Fluorolog-3). ONs were excited using 339 nm LED source (IBH, UK, NanoLED-339L) and fluorescence signal at respective emission maximum was collected (Table 1). All experiments were performed in duplicate and decay profiles were analyzed using IBH DAS6 analysis software. Fluorescence intensity decay kinetics of all ON constructs were found to be biexponential with χ2 (goodness of fit) values very close to unity.

Table 1. Quantum yield and excited-state lifetime of modified h-Telo DNA 5 and TERRA 9 GQs and corresponding duplexes in different ionic conditions.

| Sample | λem (nm) | Φa | τ1b (ns) | τ2b (ns) | τavea (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 in water (72) | 446 | 0.19 | 2.38 | – | 2.38 |

| 2 in water (71) | 447 | 0.21 | 2.55 | – | 2.55 |

| 5 in KCl | 435 | 0.11 | 0.74 (0.81) | 4.03 (0.19) | 1.40 |

| 5•8 in KCl | 430 | 0.03 | 0.56 (0.98) | 5.10 (0.02) | 0.64 |

| 5 in NaCl | 430 | 0.25 | 1.89 (0.58) | 4.50 (0.42) | 3.00 |

| 5•8 in NaCl | 430 | 0.03 | 0.57 (0.98) | 5.27 (0.02) | 0.66 |

| 9 in KCl | 440 | 0.19 | 1.53 (0.66) | 5.37 (0.34) | 2.80 |

| 9•8 in KCl | 440 | 0.04 | 0.56 (0.98) | 5.42 (0.02) | 0.65 |

| 9 in NaCl | 440 | 0.18 | 1.67 (0.67) | 5.67 (0.33) | 2.90 |

| 9•8 in NaCl | 440 | 0.04 | 0.58 (0.98) | 5.30 (0.02) | 0.67 |

aStandard deviations for quantum yield (Φ) and average lifetime (τav) are ≤0.001 and ≤0.05 ns, respectively.

bRelative amplitude is given in parenthesis.

Circular dichroism analysis

h-Telo DNA ONs 5, 6, 7 and 11 and TERRA ONs 9 and 10 (4 μM) were assembled into GQs by heating the ONs at 90°C for 3 min in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing either 100 mM KCl or 100 mM NaCl. Samples were then cooled slowly to RT and kept at 4°C for 1 h prior to CD analysis. CD spectra were collected from 350 to 220 nm on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer using 1 nm bandwidth at 20°C. Experiments were performed in duplicate wherein each spectrum was an average of five scans. The spectrum of buffer was subtracted from all sample spectra.

Thermal melting analysis

h-Telo DNA ONs 5 and 7 and TERRA ONs 9 and 10 (1 μM) were annealed by heating the ONs at 90°C for 3 min in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing either 100 mM KCl or 100 mM NaCl. Samples were then cooled slowly to RT and kept at 4°C for 1 h prior to thermal melting analysis. UV-thermal melting analysis was performed in triplicate at 260 and 295 nm by using Cary 300Bio UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

Fluorescence binding assay: binding of PDS and BRACO19 to h-Telo DNA ONs 5, 11 and TERRA 9

A series of solution of DNA and RNA GQs (0.25 μM) of 5/11 and 9, respectively, containing increasing concentrations of PDS/BRACO19 was prepared in Tris–HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 7.5) containing either 100 mM KCl or 100 mM NaCl. The concentration of ligand was increased from 13 nM to 2.5 μM. The samples were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 8 and 10 nm, respectively. A spectral blank of the buffer in the absence of ON and ligand was subtracted from all measurements. All fluorescence experiments were performed in triplicate in a micro fluorescence cuvette (Hellma, path length 1.0 cm) on a Horiba Jobin Yvon, Fluorolog-3 at 20°C. Control binding experiments with duplexes 5•8 and 9•8 were also performed under similar conditions. Normalized fluorescence intensity (FN) versus log of ligand concentration plots were fitted using Hill equation (OriginPro 8.5.1) to determine the apparent binding constant Kd for the binding of ligands to GQs (70).

|

Fi is the fluorescence intensity at each titration point. F0 and Fs are the fluorescence intensity in the absence of ligand (L) and at saturation, respectively. n is the Hill coefficient or degree of cooperativity associated with the binding.

|

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Fluorescence detection of DNA GQs

Recently, we have introduced base-modified fluorescent pyrimidine analogues derived by attaching benzofuran moiety at the 5-position of uracil (71–73). 5-Benzofuran-modified 2′-deoxyuridine (1) and uridine (2) analogues are reasonably emissive and their fluorescence properties are highly sensitive to changes in their microenvironment (Supplementary Table S1) (71,72). Unlike the majority of fluorophores, these nucleosides, when incorporated into ONs and hybridized to complementary ONs, retain appreciable fluorescence efficiency and report changes in flanking bases and base pair mismatches via changes in their fluorescence properties. These key observations and 3D structure of h-Telo DNA repeats in which the loop region (TTA) undergoes substantial conformational change upon binding to a small molecule ligand inspired us to develop the benzofuran-modified nucleoside analogue as a probe to detect GQ structures and GQ binders (Figure 1).

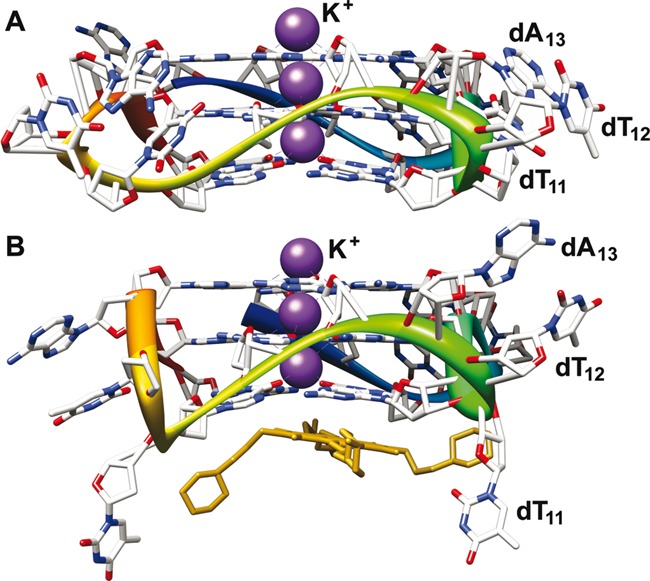

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of h-Telo DNA repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] in the presence of K+ ions. The conformation of loop residues dT11, dT12 and dA13 in the absence (A) and presence (B) of a ligand (tetrasubstituted naphthalene diimide derivative) is shown (11,23). The PDB accession numbers are 1KF1 and 4DA3, respectively. We envisaged that pyrimidine loop residues would be potential sites for introducing conformation-sensitive probes.

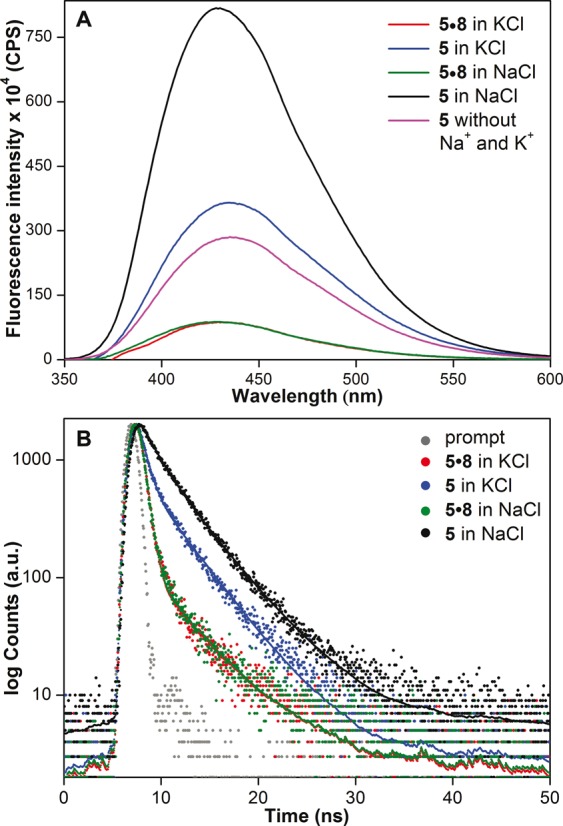

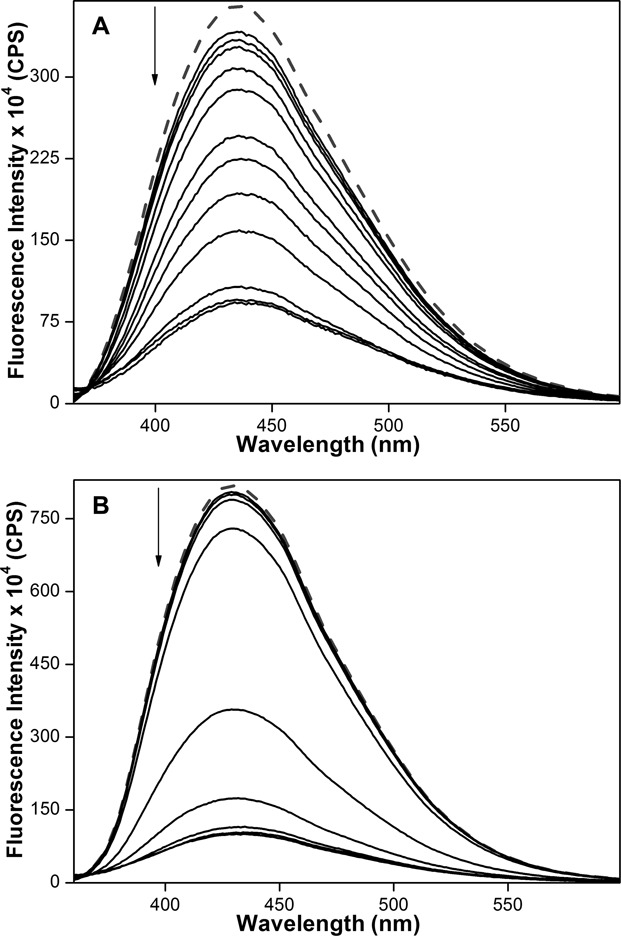

Human telomeric DNA repeats, which endcap eukaryotic chromosomes play an important role in chromosome maintenance (74,75). While aberrant shortening of telomeric repeats during cell division can result in genomic instability, the preservation of telomere length by telomerase activity in tumor cells has been implicated in carcinogenesis (76,77). Therefore, we selected h-Telo DNA repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3], which has received much of the attention, as the first test system. Phosphoramidite 3 was used in the synthesis of fluorescent h-Telo DNA ONs 5 and 6 in which the loop residues dT11 and dT12, respectively, were replaced with 5-benzofuran-modified 2′-deoxyuridine 1 (Figure 2, Supplementary Data). We purposely chose to modify the loop dT residues as modifications on guanosine could affect the efficiency of formation of GQ (67,78). The integrity of full-length modified h-Telo DNA ONs 5 and 6 was confirmed by mass and HPLC analyses (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S2). Steady-state fluorescence analysis of ONs 5 and 6 in a buffer solution containing KCl or NaCl (100 mM) was performed by exciting the samples at 330 nm. Telomeric DNA 5, which could form hybrid-type of mixed parallel-antiparallel stranded GQ in K+, displayed a significantly higher fluorescence intensity (∼4 fold at λem = 435 nm) as compared to corresponding perfect duplex 5•8 (Figure 3A). Remarkably, 5 in the presence of Na+ ions, which is known to induce antiparallel GQ structure exhibited a nearly 9-fold enhancement in fluorescence intensity as compared to duplex 5•8 with no apparent change in emission maximum. Further, time-resolved fluorescence measurements revealed distinct decay kinetics for different GQ topologies. The antiparallel GQ structure of 5 exhibited the highest lifetime of 3.00 ns followed by mixed-type GQ (1.40 ns) and duplex 5•8 (0.64 ns and 0.66 ns) in the presence of K+ and Na+ ions (Figure 3B, Table 1). This trend in lifetime was found to be consistent with the trend in emission intensity observed in steady-state experiments. The difference in emission intensity and lifetime exhibited by h-Telo DNA ON 5 in K+ and Na+ is likely due to distinctly different conformation of the fluorescent nucleoside in these two different topologies.

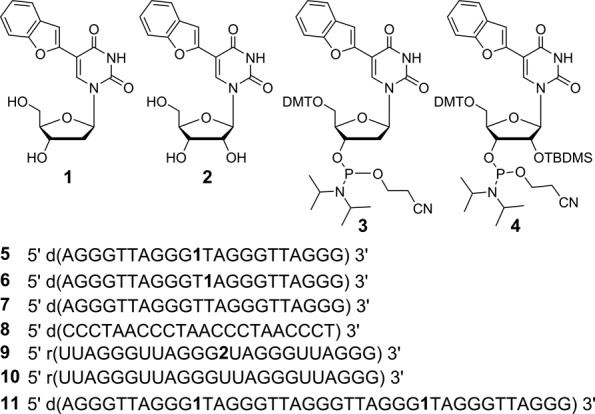

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of 5-benzofuran-modified 2′-deoxyuridine (1) and uridine (2) analogues, and corresponding phosphoramidite substrates 3 and 4 used in the synthesis of GQ-forming DNA and RNA ONs (5, 6, 9 and 11). 5 and 6 are fluorescent h-Telo DNA ONs containing the modification at position 11 and 12, respectively. ON 7 is a control unmodified h-Telo DNA and 8 is complementary to h-Telo DNA 5−7. 9 and 10 are modified and control unmodified TERRA ONs, respectively. Sequence of doubly modified longer h-Telo DNA repeat 11 used in this study (Supplementary Data).

Figure 3.

(A) Steady-state and (B) time-resolved fluorescence spectra of h-Telo DNA 5 and corresponding duplex 5•8 in the presence of K+ or Na+ ions. Laser profile is shown in gray (prompt). Fluorescence spectrum of ON 5 (magenta) in buffer without added Na+ and K+ ions is also shown. ONs (0.25 μM) were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 8 and 10 nm, respectively.

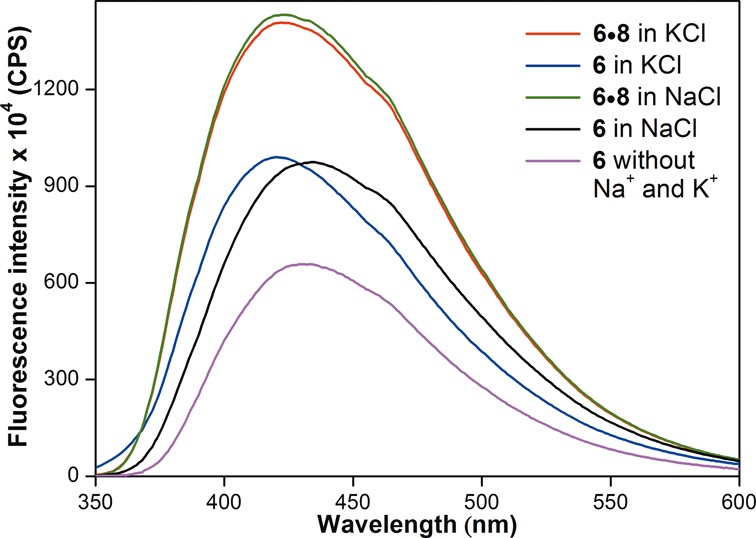

Interestingly, the efficiency of sensing of different GQ topologies by emissive nucleoside was found to depend on the position of modification. ON 6, containing the emissive nucleoside 1 at position 12, in the presence of Na+ or K+ ions displayed reasonable quenching in fluorescence intensity as compared to duplex 6•8 (Figure 4). Albeit small difference in emission maximum, ON 6 failed to distinguish between different GQ structures in Na+ and K+ ionic conditions. Based on emission maximum, the fluorescent nucleoside 1 in h-Telo DNA ON 5 in the presence of K+ and Na+ ions (∼435 nm) is slightly less solvent exposed than the free nucleoside (447 nm, Table 1). While the emissive nucleoside in ON 6 in the presence of Na+ ions (435 nm) is solvated similar to ON 5 in the presence of K+ and Na+ ions, it is even more less exposed to solvent in ON 6 in the presence of K+ ions (420 nm).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence spectra of h-Telo DNA 6 and corresponding duplex 6•8 in the presence of K+ or Na+ ions. Fluorescence spectrum of ON 6 (magenta) in buffer without added Na+ and K+ ions is also shown. ONs (0.25 μM) were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 8 and 10 nm, respectively. See Supplementary Figure S2 for comparison of fluorescence intensity of GQs of ONs 5 and 6.

Fluorescence detection of RNA GQs

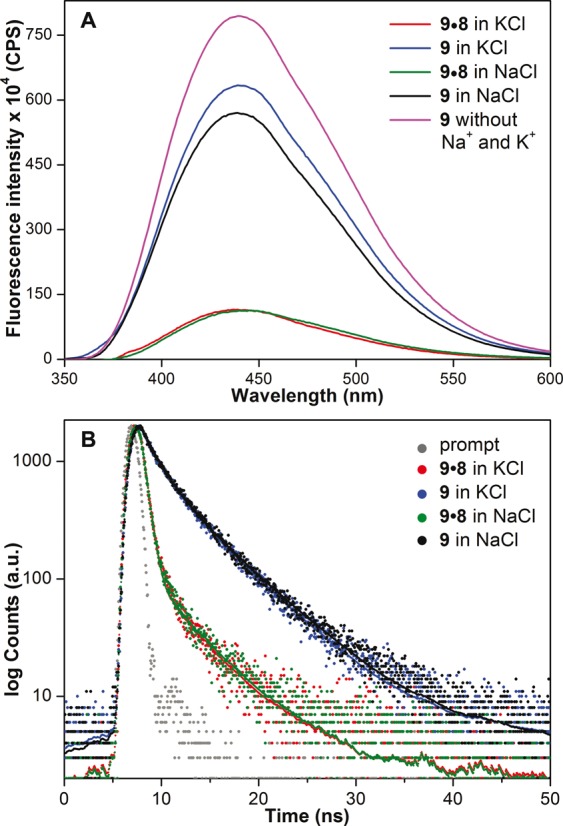

While most efforts in the study of GQ structures have been dedicated toward developing probes for DNA GQs, probe development for RNA GQs has received less attention. Therefore, we wanted to explore the efficacy of our emissive nucleoside in detecting the formation of RNA GQ structures. For this purpose, we chose TERRA composed of extended tandem repeats of (U2AG3)n, which has been considered to play important role in telomere structure maintenance and replication (79,80). RNA GQs formed in vitro under near physiological conditions are thermodynamically more stable than their DNA counterparts, and have been shown to form parallel-stranded GQ structure in both Na+ and K+ ionic conditions (14,15). The counterpart of h-Telo DNA 5, TERRA ON 9 (U2AG3)4, containing benzofuran-modified uridine analogue 2 at loop residue was synthesized by using phosphoramidite 4 (Figure 2, Supplementary Data, Supplementary Table S2). Upon excitation, RNA 9 in the presence of K+ and Na+ ions displayed a significant and comparable enhancement in fluorescence intensity (∼5-fold) as compared to corresponding duplex 9•8 (Figure 5A). Excited-state decay kinetics analysis of 9 also revealed a similar lifetime of 2.80 and 2.90 ns in K+ and Na+ ions, respectively, which was nearly four times higher than that of duplex (Figure 5B, Table 1). These results clearly indicate that the conformation and microenvironment of the emissive nucleoside incorporated into 9 in K+ and Na+ are similar and consistent with the formation of parallel GQ structure expected for TERRA ON irrespective of ionic conditions (14,15). It is worth mentioning here that a fluorescent adenine analogue, 2AP, when incorporated into the loop region of h-Telo DNA repeat exhibits emission maximum in the UV region (λem = 370 nm) and much lower quantum yield (0.06) as compared to benzofuran-modified h-Telo DNA and TERRA GQs (Table 1) (81). This is because guanine is known to effectively quench the fluorescence of 2AP in ONs by electron transfer mechanism (68).

Figure 5.

(A) Steady-state and (B) time-resolved fluorescence spectra of TERRA 9 and corresponding duplex 9•8 in the presence of K+ or Na+ ions. Laser profile is shown in gray (prompt). Fluorescence spectrum of ON 9 (magenta) in buffer without added Na+ and K+ ions is also shown. ONs (0.25 μM) were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 8 and 10 nm, respectively.

We believe that distinct fluorescence properties such as emission maximum, quantum yield and lifetime exhibited by DNA and RNA GQ structures of 5 and 9, and corresponding duplexes in different ionic conditions are due to distinct conformation and microenvironment of emissive nucleosides in these constructs. As a consequence, the observed enhancement in fluorescence intensity displayed by GQs as compared to duplexes can be possibly due to a combination of the following reasons: solvation-desolvation effect, rigidification of the fluorophore, reduced electron transfer process and stacking interaction between the emissive nucleobase and neighbouring bases in GQs as compared to base-paired emissive nucleobase in duplexes (68,82). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate the ability of benzofuran-modified nucleosides to distinguish different GQ topologies based on ionic conditions and nucleic acid type.

Circular dichroism and thermal melting studies

Benzofuran modification in h-Telo DNA 5 and TERRA 9 could potentially affect the formation and stability of GQ structures. Circular dichroism (CD) analysis of modified ONs 5 and 9, and corresponding unmodified ONs 7 and 10, respectively, in the presence of Na+ or K+ ions confirmed the formation of respective topologies thereby indicating that the modification did not hamper the formation of GQs (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). In the presence of K+ ions h-Telo DNA ONs 5 and 7 exhibit a positive peak at ∼290 nm, a smaller shoulder at ∼270 nm and a smaller minimum at ∼ 235 nm, which closely resemble the CD pattern of hybrid-type of mixed parallel-antiparallel stranded GQ structure. Such a CD profile has been observed for the same sequence in earlier reports (12,83). In the presence of Na+ ions h-Telo DNA ONs 5 and 7 exhibit CD pattern (positive peak at ∼290 nm and strong negative peak at ∼265 nm) characteristic of antiparallel stranded GQ structure (10,84). On the other hand, irrespective of ionic conditions both modified and unmodified TERRA ONs show similar CD profiles characteristic of parallel stranded GQ structure (14,84). Furthermore, UV-thermal melting analysis of modified and unmodified GQ-forming ONs in different ionic conditions gave similar Tm values (ΔTm ≤ 2°C) suggesting that the benzofuran modification had only a minor impact on GQ stability (Supplementary Figure S5, Supplementary Table S3) (85).

Topology-specific binding of small-molecules to DNA and RNA GQ structures

Next, we sought to explore the compatibility of these GQ sensors in estimating topology-specific binding of small-molecules to different GQ structures. For this purpose, we chose two known GQ binders, pyridostatin (PDS) and BRACO19, which have been used as tools for biophysical and therapeutic analysis of GQ structures (Figure 6) (86,87). Fluorescent h-Telo DNA 5 was assembled into mixed-type and antiparallel GQs in buffers containing KCl and NaCl, respectively. GQs of 5 were excited at 330 nm and changes in fluorescence intensity upon addition of increasing concentrations of a ligand were monitored. Addition of PDS to mixed-type GQ resulted in a nearly 4-fold quenching in fluorescence intensity at the saturation concentration of PDS (2.5 μM, Figure 7A). The saturation binding isotherm yielded an apparent Kd of 919 ± 7 nM, which is comparable to literature report (Supplementary Figure S6) (88). Interestingly, binding of PDS to antiparallel GQ in Na+ resulted in a concentration-dependent decrease in fluorescence intensity, which was significantly pronounced as compared to in the presence of K+ (8-fold at PDS = 1.5 μM, Figure 7B). The Kd value (440 ± 21 nM) indicated that PDS has higher binding affinity for antiparallel h-Telo DNA GQ as compared to mixed-type h-Telo DNA GQ structure (Table 2). The fluorescent nucleoside also reported the binding of BRACO19 to both mixed-type and antiparallel GQs of 5 with significant quenching in fluorescence intensity (Supplementary Figure S7). BRACO19 exhibited opposite binding affinities for GQs as compared to PDS (Table 2). While BRACO19 binding to mixed-type h-Telo DNA GQ was found to be stronger than PDS, binding of BRACO19 to antiparallel DNA GQ was weaker compared to PDS.

Figure 6.

Chemical structure of GQ binders, pyridostatin (PDS) and BRACO19.

Figure 7.

Emission spectra (solid lines) of mixed-type (A) and antiparallel (B) GQs of h-Telo DNA 5 (0.25 μM) in the presence of K+ and Na+ ions, respectively, with increasing concentrations of PDS. Dashed lines represent emission profile of GQs in the absence of PDS. ONs were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 8 and 10 nm, respectively.

Table 2. Binding constant (Kd) for PDS and BRACO19 binding to h-Telo DNA 5 and TERRA 9a.

| ON | PDS (nM) | BRACO19 (nM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in KCl | in NaCl | in KCl | in NaCl | |

| 5 | 919 ± 07 | 440 ± 21 | 476 ± 25 | 938 ± 29 |

| 9 | 260 ± 10 | 268 ± 12 | 294 ± 04 | 244 ± 11 |

| 11 | n.d. | 539 ± 19 | 483 ± 23 | 462 ± 17 |

aFor curve fits see Supplementary Figures S6–S9. n.d. = not determined (Although addition of PDS to 11 in the presence of KCl resulted in fluorescence quenching, reliable binding constant could not be determined).

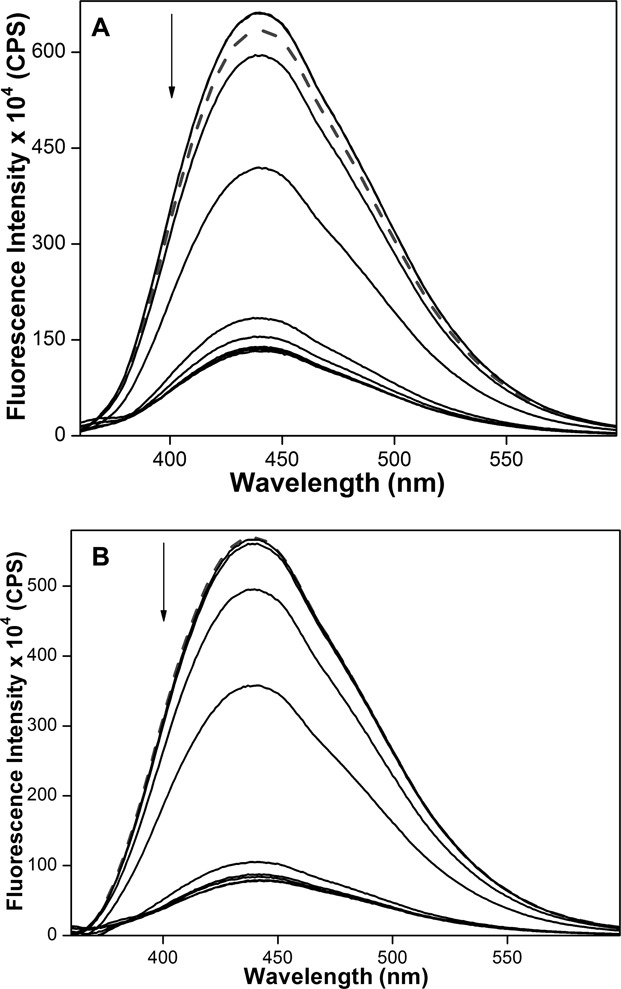

High-resolution structures of TERRA have revealed distinct features of RNA GQs involving 2′-hydroxyl group and loop residues that are not found in DNA GQs (15). These studies suggest the possibility of developing small-molecule ligands that can selectively bind GQs based on nucleic acid type (89). TERRA ON 9, which forms parallel GQ structure in both K+ and Na+ ionic conditions, was subjected to binding studies. Concentration-dependent quenching in fluorescence intensity signalled the binding of PDS and BRACO19 to 9 (Figure 8, and Supplementary Figures S8 and S9). The ligands exhibited significantly higher but similar binding affinities for TERRA as compared to h-Telo DNA in the presence of K+ and Na+ ions (Table 2). These results are consistent with the ability of TERRA ON 9 to form one type of stable GQ structure (i.e., parallel) as compared to corresponding DNA sequence, irrespective of ionic conditions. Importantly, control binding experiments with nucleoside 1 and duplexes of h-Telo DNA (5•8) and TERRA (9•8) resulted only in minor changes in fluorescence intensity indicating that the nucleoside incorporated into ONs 5 and 9 signalled only the specific binding of ligands to GQ structures (Supplementary Figure S10). In the absence of structural analysis, fluorescence quenching displayed by GQs of 5 and 9 is possibly due to the conformation attained by emissive nucleosides upon ligand binding, which is less rigid and appropriately positioned for nonradiative interactions with neighbouring bases and or ligands (68,90,91). Further, differential binding affinities exhibited by PDS and BRACO19 for DNA and RNA GQs could be ascribed to the differences in chemical environment and conformation of G-tetrads of GQ assemblies (53). Collectively, these observations highlight the potential of benzofuran-modified nucleoside analogues as probes for quantitative estimation of structure-specific binding of ligands to GQ structures.

Figure 8.

Emission spectra (solid lines) of parallel GQ of TERRA 9 (0.25 μM) in the presence of K+ (A) and Na+ (B) ions, respectively, with increasing concentrations of PDS. Dashed lines represent emission profile of GQs in the absence of PDS. ONs were excited at 330 nm with excitation and emission slit widths of 8 and 10 nm, respectively.

Binding of ligands to higher-order h-Telo DNA GQ structures

The telomeric DNA, which terminates in a 100−200 bases 3′ single stranded overhang of G-rich hexameric repeats, can form higher-order GQ structures (e.g. dimer or multimer) (92,93). Such consecutive GQ units have been also considered as a potential target as they play an important role in recognition and function of telomeric DNA. We synthesized longer h-Telo DNA repeat 11 containing two modifications, which could form two consecutive GQ units (94). The CD and fluorescence profiles of ON 11 in the presence of KCl and NaCl revealed the formation of mixed-type and antiparallel GQ structures, respectively (Supplementary Figure S11). Akin to ON 5, addition of increasing concentrations of PDS and BRACO19 resulted in concentration-dependent decrease in fluorescence intensity, which however, yielded similar binding constants in both Na+ and K+ ionic conditions (Table 2). These results underscore the potential utility of emissive nucleoside in studying the structure as well as in identifying higher-order GQ binders.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Environment-sensitive and minimally perturbing 5-benzofuran-modified 2′-deoxyuridine (1) and uridine (2) analogues, when incorporated into one of the loop residues of human telomeric DNA and RNA ONs, reported the formation of different DNA and RNA GQ structures with significant enhancement in fluorescence intensity. These GQ sensors also enabled the development of a simple fluorescence method to detect and quantify topology- and nucleic acid-specific binding of ligands to GQ structures. Although many fluorescent purine nucleosides analogues have been used in the study of DNA GQs, their use in the discrimination of different GQ topologies based on nucleic acid type and in the quantitative estimation of ligands binding to DNA and RNA GQs has not been well explored (35). Moreover, some of the easily accessible analogues (e.g. 2-AP, 6-MI, furyl-dG), though exhibit enhancement in fluorescence depending on the position of incorporation, significantly destabilize the GQ structures (66,67,78). Hence, implementation of such probes in screening formats to identify efficient GQ binders may not be feasible. In this context, our experiments indicate that benzofuran-modified nucleoside analogues can serve as useful probes for DNA and RNA GQs and provide an efficient platform to identify topology- and nucleic acid-specific GQ binders of therapeutic potential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SGS thanks CSIR, India (02-0086/12/EMR-II) for the research grant. A.A.T. thanks CSIR, India for the graduate research fellowship.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Funding for open access charge: Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune and development allowance to SGS.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel D.J., Phan A.T., Kuryavyi V. Human telomere, oncogenic promoter and 5′-UTR G-quadruplexes: diverse higher order DNA and RNA targets for cancer therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7429–7455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian S., Hurley L.H., Neidle S. Targeting G-quadruplexes in gene promoters: a novel anticancer strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:261–275. doi: 10.1038/nrd3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collie G.W., Parkinson G.N. The application of DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes to therapeutic medicines. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5867–5892. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15067g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rankin S., Reszka A.P., Huppert J., Zloh M., Parkinson G.N., Todd A.K., Ladame S., Balasubramanian S., Neidle S. Putative DNA quadruplex formation within the human c-kit oncogene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10584–10589. doi: 10.1021/ja050823u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumari S., Bugaut A., Huppert J.L., Balasubramanian S. An RNA G-quadruplex in the 5′ UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene modulates translation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:218–221. doi: 10.1038/nchembio864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Y.-L., Hu N., Sun Q., Wang C., Taylor P.R. Telomere attrition in cancer cells and telomere length in tumor stroma cells predict chromosome instability in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a genome-wide analysis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1604–1614. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phan A.T. Human telomeric G-quadruplex: structures of DNA and RNA sequences. FEBS J. 2010;277:1107–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran P.L.T., Mergny J.-L., Alberti P. Stability of telomeric G-quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3282–3294. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S., Wu Y., Zhang W. G-quadruplex structures and their interaction diversity with ligands. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:899–911. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y., Patel D.J. Solution structure of the human telomeric repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] G-tetraplex. Structure. 1993;1:263–282. doi: 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkinson G.N., Lee M.P.H., Neidle S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature. 2002;417:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrus A., Chen D., Dai J., Bialis T., Jones R.A., Yang D. Human telomeric sequence forms a hybrid-type intramolecular G-quadruplex structure with mixed parallel/antiparallel strands in potassium solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2723–2735. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lannan F.M., Mamajanov I., Hud N.V. Human telomere sequence DNA in water-free and high-viscosity solvents: G-quadruplex folding governed by Kramers rate theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15324–15330. doi: 10.1021/ja303499m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y., Kaminaga K., Komiyama M. G-quadruplex formation by human telomeric repeats-containing RNA in Na+ solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11179–11184. doi: 10.1021/ja8031532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martadinata H., Phan A.T. Structure of propeller-type parallel-stranded RNA G-quadruplexes, formed by human telomeric RNA sequences in K+ solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2570–2578. doi: 10.1021/ja806592z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Cian A., Lacroix L., Douarre C., Temime-Smaali N., Trentesaux C., Riou J.-F., Mergny J.-L. Targeting telomeres and telomerase. Biochimie. 2008;90:131–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monchaud D., Teulade-Fichou M.-P. A hitchhiker's guide to G-quadruplex ligands. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:627–636. doi: 10.1039/b714772b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgiades S.N., Abd Karim N.H., Suntharalingam K., Vilar R. Interaction of metal complexes with G-quadruplex DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4020–4034. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y., Komiyama M. Structure, function and targeting of human telomere RNA. Methods. 2012;57:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boddupally P.V.L., Hahn S., Beman C., De B., Brooks T.A., Gokhale V., Hurley L.H. Anticancer activity and cellular repression of c-MYC by the G-quadruplex-stabilizing 11-piperazinylquindoline is not dependent on direct targeting of the G-quadruplex in the c-MYC promoter. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:6076–6086. doi: 10.1021/jm300282c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicoludis J.M., Barrett S.P., Mergny J.-L., Yatsunyk L.A. Interaction of human telomeric DNA with N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5432–5447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohanty J., Barooah N., Dhamodharan V., Harikrishna S., Pradeepkumar P.I., Bhasikuttan A.C. Thioflavin T as an efficient inducer and selective fluorescent sensor for the human telomeric G-quadruplex DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:367–376. doi: 10.1021/ja309588h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micco M., Collie G.W., Dale A.G., Ohnmacht S.A., Pazitna I., Gunaratnam M., Reszka A.P., Neidle S. Structure-based design and evaluation of naphthalene diimide G-quadruplex ligands as telomere targeting agents in pancreatic cancer cells. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:2959–2974. doi: 10.1021/jm301899y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal T., Lalwani M.K., Kumar S., Roy S., Chakraborty T.K., Sivasubbu S., Maiti S. Morphological effects of G-quadruplex stabilization using a small molecule in zebrafish. Biochemistry. 2014;53:1117–1124. doi: 10.1021/bi4009352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung W.J., Heddi B., Hamon F., Teulade-Fichou M.-P., Phan A.T. Solution structure of a G-quadruplex bound to the bisquinolinium compound Phen-DC(3) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:999–1002. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laguerre A., Desbois N., Stefan L., Richard P., Gros C.P., Monchaud D. Porphyrin-based design of bioinspired multitarget quadruplex ligands. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:2035–2039. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu Z., Han M., Cowan J.A. Toward the design of a catalytic metallodrug: selective cleavage of G-quadruplex telomeric DNA by an anticancer copper-acridine-ATCUN complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:1901–1905. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paeschke K., Juranek S., Simonsson T., Hempel A., Rhodes D., Lipps H.J. Telomerase recruitment by the telomere end binding protein-beta facilitates G-quadruplex DNA unfolding in ciliates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:598–604. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y., Suzuki Y., Ito K., Komiyama M. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA structure in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:14579–14584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001177107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biffi G., Tannahill D., McCafferty J., Balasubramanian S. Quantitative visualization of DNA G-quadruplex structures in human cells. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:182–186. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lam E.Y.N., Beraldi D., Tannahill D., Balasubramanian S. G-quadruplex structures are stable and detectable in human genomic DNA. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1796. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson A., Wu Y., Huang Y.C., Chavez E.A., Platt J., Johnson F.B., Brosh R.M. Jr, Sen D., Lansdrop P.M. Detection of G-quadruplex DNA in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:860–869. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu R.-Y., Zheng K.-W., Zhang J.-Y., Hao Y.-H., Tan Z. Formation of DNA:RNA hybrid G-quadruplex in bacterial cells and its dominance over the intramolecular DNA G-quadruplex in mediating transcription termination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:2447–2451. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laguerre A., Hukezalie K., Winckler P., Katranji F., Chanteloup G., Pirrotta M., Perrier-Cornet J.-M., Wong J.M.Y., Monchaud D. Visualization of RNA-quadruplexes in live cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03413. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b03413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vummidi B.R., Alzeer J., Luedtke N.W. Fluorescent probes for G-quadruplex structures. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:540–558. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Largy E., Granzhan A., Hamon F., Verga D., Teulade-Fichou M.P. Visualizing the quadruplex: from fluorescent ligands to light-up probes. Top. Curr. Chem. 2013;330:111–177. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhasikuttan A.C., Mohanty J. Targeting G-quadruplex structures with extrinsic fluorogenic dyes: promising fluorescence sensors. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:7581–7597. doi: 10.1039/c4cc10030a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drygin D., Siddiqui-Jain A., O'Brien S., Schwaebe M., Lin A., Bliesath J., Ho C.B., Proffitt C., Trent K., Whitten J.P., et al. Anticancer activity of CX-3543: a direct inhibitor of rRNA biogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7653–7661. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mergny J.-L., Maurizot J.-C. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer as a probe for G-quartet formation by a telomeric repeat. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:124–132. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010202)2:2<124::AID-CBIC124>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueyama H., Takagi M., Takenaka S. A novel potassium sensing in aqueous media with a synthetic oligonucleotide derivative. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer associated with Guanine quartet-potassium ion complex formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14286–14287. doi: 10.1021/ja026892f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darby R.A., Sollogoub M., McKeen C., Brown L., Risitano A., Brown N., Barton C., Brown T., Fox K.R. High throughput measurement of duplex, triplex and quadruplex melting curves using molecular beacons and a LightCycler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e39. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Risitano A., Fox K.R. Stability of intramolecular DNA quadruplexes: comparison with DNA duplexes. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6507–6513. doi: 10.1021/bi026997v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ying L., Green J.J., Li H., Klenerman D., Balasubramanian S. Studies on the structure and dynamics of the human telomeric G quadruplex by single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:14629–14634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433350100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagatoishi S., Nojima T., Galezowska E., Juskowiak B., Takenaka S. G quadruplex-based FRET probes with the thrombin-binding aptamer (TBA) sequence designed for the efficient fluorometric detection of the potassium ion. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1730–1737. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takenaka S., Juskowiak B. Fluorescence detection of potassium ion using the G-quadruplex structure. Anal. Sci. 2011;27:1167–1172. doi: 10.2116/analsci.27.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohtsuka K., Sato S., Sato Y., Sota K., Ohzawa S., Matsuda T., Takemoto K., Takamune N., Juskowiak B., Nagai T., et al. Fluorescence imaging of potassium ions in living cells using a fluorescent probe based on a thrombin binding aptamer-peptide conjugate. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:4740–4742. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30536d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang H., Ji J., Liu Y., Kong J., Liu B. An aptamerbased biosensor for sensitive thrombin detection. Electrochem. Commun. 2009;11:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J.J., Fang X., Tan W. Molecular aptamer beacons for real-time protein recognition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;292:31–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Tito S., Morvan F., Meyer A., Vasseur J.J., Cummaro A., Petraccone L., Pagano B., Novellino E., Randazzo A., Giancola C., et al. Fluorescence enhancement upon G-quadruplex folding: synthesis, structure, and biophysical characterization of a dansyl/cyclodextrin-tagged thrombin binding aptamer. Bioconjug. Chem. 2013;24:1917–1927. doi: 10.1021/bc400352s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lacroix L., Séosse A., Mergny J.L. Fluorescence-based duplex-quadruplex competition test to screen for telomerase RNA quadruplex ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benz A., Singh V., Mayer T.U., Hartig J.S. Identification of novel quadruplex ligands from small molecule libraries by FRET-based high-throughput screening. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1422–1426. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagatoishi S., Nojima T., Juskowiak B., Takenaka S. A pyrene-labeled G-quadruplex oligonucleotide as a fluorescent probe for potassium ion detection in biological applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:5067–5070. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Le D.D., Antonio M.D., Chan L.K.M., Balasubramanian S. G-quadruplex ligands exhibit differential G-tetrad selectivity. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:8048–8050. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02252e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nikan M., Di Antonio M., Abecassis K., McLuckie K., Balasubramanian S. An acetylene-bridged 6,8-purine dimer as a fluorescent switch-on probe for parallel G-quadruplexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:1428–1431. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iida K., Nakamura T., Yoshida W., Tera M., Nakabayashi K., Hata K., Ikebukuro K., Nagasawa K. Fluorescent-ligand-mediated screening of G-quadruplex structures using a DNA microarray. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:12052–12055. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laguerre A., Stefan L., Larrouy M., Genest D., Novotna J., Pirrotta M., Monchaud D. A twice-as-smart synthetic G-quartet: PyroTASQ is both a smart quadruplex ligand and a smart fluorescent probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12406–12414. doi: 10.1021/ja506331x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao D., Dong X., Jiang N., Zhang D., Liu C. Selective recognition of parallel and anti-parallel thrombin-binding aptamer G-quadruplexes by different fluorescent dyes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:11612–11621. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Myers J.C., Moore S.A., Shamoo Y. Structure-based incorporation of 6-methyl-8-(2-deoxy-beta-ribofuranosyl)isoxanthopteridine into the human telomeric repeat DNA as a probe for UP1 binding and destabilization of G-tetrad structures. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42300–42306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li J., Correia J.J., Wang L., Trent J.O., Chaires J.B. Not so crystal clear: the structure of the human telomere G-quadruplex in solution differs from that present in a crystal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4649–4659. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura T., Kawai K., Fujitsuka M., Majima T. Detection of the G-quadruplex-TMPyP4 complex by 2-aminopurine modified human telomeric DNA. Chem. Commun. 2006:401–402. doi: 10.1039/b514526k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kimura T., Kawai K., Fujitsuka M., Majima T. Monitoring G-quadruplex structures and G-quadruplex–ligand complex using 2-aminopurine modified oligonucleotides. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3585–3590. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gray R.D., Petraccone L., Trent J.O., Chaires J.B. Characterization of a K+-Induced Conformational Switch in a Human Telomeric DNA Oligonucleotide Using 2-Aminopurine Fluorescence. Biochemistry. 2010;49:179–194. doi: 10.1021/bi901357r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dumas A., Luedtke N.W. Highly fluorescent guanosine mimics for folding and energy transfer studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6825–6834. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sproviero M., Fadock K.L., Witham A.A., Manderville R.A., Sharma P., Wetmore S.D. Electronic tuning of fluorescent 8-aryl-guanine probes for monitoring DNA duplex–quadruplex exchange. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:788–796. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nadler A., Strohmeier J., Diederichsen U. 8-Vinyl-2-deoxyguanosine as a Fluorescent 2′-Deoxyguanosine Mimic for Investigating DNA Hybridization and Topology. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:5392–5396. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson J., Okyere R., Joseph A., Musier-Forsyth K., Kankia B. Quadruplex formation as a molecular switch to turn on intrinsically fluorescent nucleotide analogs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:220–228. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sproviero M., Fadock K.L., Witham A.A., Manderville R.A. Positional Impact of Fluorescently Modified G-Tetrads within Polymorphic Human Telomeric G-Quadruplex Structures. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:1311–1318. doi: 10.1021/cb5009926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doose S., Neuweiler H., Sauer M. Fluorescence quenching by photoinduced electron transfer: a reporter for conformational dynamics of macromolecules. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10:1389–1398. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lavabre D., Fery-Forgues S.J. Are fluorescence quantum yields so tricky to measure? A demonstration using familiar stationery products. Chem. Educ. 1999;76:1260–1264. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tam V.K., Kwong D., Tor Y. Fluorescent HIV-1 dimerization initiation site: design, properties, and use for ligand discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3257–3266. doi: 10.1021/ja0675797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tanpure A.A., Srivatsan S.G. A microenvironment-sensitive fluorescent pyrimidine ribonucleoside analogue: synthesis, enzymatic incorporation, and fluorescence detection of a DNA abasic site. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:12820–12827. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tanpure A.A., Srivatsan S.G. Synthesis and photophysical characterisation of a fluorescent nucleoside analogue that signals the presence of an abasic site in RNA. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:2392–2399. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sabale P.M., George J.T., Srivatsan S.G. A base-modified PNA-graphene oxide platform as a turn-on fluorescence sensor for the detection of human telomeric repeats. Nanoscale. 2014;6:10460–10469. doi: 10.1039/c4nr00878b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blackburn E.H. The end of the (DNA) line. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:847–850. doi: 10.1038/79594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Verdun R.E., Karlseder J. Replication and protection of telomeres. Nature. 2007;447:924–931. doi: 10.1038/nature05976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shay J.W., Roninson I.B. Hallmarks of senescence in carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2004;23:2919–2933. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng Y.-L., Hu N., Sun Q., Wang C., Taylor P.R. Telomere attrition in cancer cells and telomere length in tumor stroma cells predict chromosome instability in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a genome-wide analysis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1604–1614. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gros J., Rosu F., Amrane S., De Cian A., Gabelica V., Lacroix L., Mergny J.-L. Guanines are a quartet's best friend: impact of base substitutions on the kinetics and stability of tetramolecular quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3064–3075. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Azzalin C.M., Reichenbach P., Khoriauli L., Giulotto E., Lingner J. Telomeric repeat containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends. Science. 2007;318:798–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1147182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schoeftner S., Blasco M.A. Developmentally regulated transcription of mammalian telomeres by DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:228–236. doi: 10.1038/ncb1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kimura T., Kawai K., Fujitsuka M., Majima T. Fluorescence properties of 2-aminopurine in human telomeric DNA. Chem. Commun. 2004:1438–1439. doi: 10.1039/b403913k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tanpure A.A., Pawar M.G., Srivatsan S.G. Fluorescent nucleoside analogs: probes for investigating nucleic acid structure and function. Isr. J. Chem. 2013;53:366–378. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xue Y., Kan Z-Y., Wang Q., Yao Y., Liu J., Hao Y-H., Tan Z. Human telomeric DNA forms parallel-stranded intramolecular G-quadruplex in K+ solution under molecular crowding condition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11185–11191. doi: 10.1021/ja0730462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Biffi G., Tannahill D., Balasubramanian S. An intramolecular G-quadruplex structure is required for binding of telomeric repeat-containing RNA to the telomeric protein TRF2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:11974–11976. doi: 10.1021/ja305734x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rachwal P.A., Fox K.R. Quadruplex melting. Methods. 2007;43:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moore M.J.B., Schultes C.M., Cuesta J., Cuenca F., Gunaratnam M., Tanious F.A., Wilson W.D., Neidle S. Trisubstituted acridines as G-quadruplex telomere targeting agents. Effects of extensions of the 3,6- and 9-side chains on quadruplex binding, telomerase activity, and cell proliferation. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:582–599. doi: 10.1021/jm050555a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rodriguez R., Müller S., Yeoman J.A., Trentesaux C., Riou J.-F., Balasubramanian S. A novel small molecule that alters shelterin integrity and triggers a DNA-damage response at telomeres. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15758–15759. doi: 10.1021/ja805615w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koirala D., Dhakal S., Ashbridge B., Sannohe Y., Rodriguez R., Sugiyama H., Balasubramanian S., Mao H. A single-molecule platform for investigation of interactions between G-quadruplexes and small-molecule ligands. Nat Chem. 2011;3:782–787. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Collie G.W., Sparapani S., Parkinson G.N., Neidle S. Structural basis of telomeric RNA quadruplex–acridine ligand recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2721–2728. doi: 10.1021/ja109767y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sinkeldam R.W., Wheat A.J., Boyaci H., Tor Y. Emissive nucleosides as molecular rotors. ChemPhysChem. 2011;12:567–570. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201001002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wilhelmsson L.M. Fluorescent nucleic acid base analogues. Quart. Rev. Biophy. 2010;43:159–183. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xu Y., Ishizuka T., Kurabayashi K., Komiyama M. Consecutive formation of G-quadruplexes in human telomeric-overhang DNA: a protective capping structure for telomere ends. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7833–7836. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Petraccone L. Higher-order quadruplex structures. Top Curr. Chem. 2013;330:23–46. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhao C., Wu L., Ren J., Xu Y., Qu X. Targeting human telomeric higher-order DNA: dimeric G-quadruplex units serve as preferred binding site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:18786–18789. doi: 10.1021/ja410723r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.