Abstract

Objective

To conduct a systematic review to examine interventions for reducing HIV risk behaviors among people living with HIV (PLWH) in the United States.

Methods

Systematic searches included electronic databases from 1988 to 2012, hand searches of journals, reference lists of articles, and HIV/AIDS Internet listservs. Each eligible study was evaluated against the established criteria on study design, implementation, analysis, and strength of findings to assess the risk of bias and intervention effects.

Results

Forty-eight studies were evaluated. Fourteen studies (29%) with both low risk of bias and significant positive intervention effects in reducing HIV transmission risk behaviors were classified as evidence-based interventions (EBIs). Thirty-four studies were classified as non-EBIs due to high risk of bias or non-significant positive intervention effects. EBIs varied in delivery from brief prevention messages to intensive multi-session interventions. The key components of EBIs included addressing HIV risk reduction behaviors, motivation for behavioral change, misconception about HIV, and issues related to mental health, medication adherence, and HIV transmission risk behavior.

Conclusion

Moving evidence-based prevention for PLWH into practice is an important step in making a greater impact on the HIV epidemic. Efficacious EBIs can serve as model programs for providers in healthcare and non-healthcare settings looking to implement evidence-based HIV prevention. Clinics and public health agencies at the state, local, and federal levels can use the results of this review as a resource when making decisions that meet the needs of PLWH to achieve the greatest impact on the HIV epidemic.

Keywords: HIV prevention, evidence based intervention, people living with HIV, risk reduction, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, it is estimated that 1,144,500 persons aged 13 and older were living with HIV at the end of 2010 [1] and there were an estimated 47,500 new HIV infections in 2010 [2]. People living with HIV (PLWH) are key partners in reducing the number of new HIV infections. Many PLWH reduce their risk behaviors after learning about their HIV-seropositive status [3, 4]. However, adopting and maintaining safer behaviors can be challenging for some [5, 6]. Providing prevention interventions that reduce the risk of HIV transmission or acquisition of other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), in addition to HIV treatment and care for improving the health of PLWH, are critical components of the U.S. National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) [7]. Identifying evidence-based interventions (EBIs) to help PLWH protect themselves and uninfected partners is considered to be the high priority of NHAS.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews [8–10] show that behavioral interventions for PLWH significantly reduce sexual risk behaviors. These systematic reviews are useful for understanding the overall effect on reducing HIV risk behaviors among PLWH. However, these reviews typically do not critically assess the quality of evidence by closely examining study design, implementation, analysis, and findings of individual interventions. Several evidence-based review groups such as the Cochrane Collaboration [11] and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)[12] have emphasized the importance of assessing the risk of bias of individual studies as part of assessing the body of evidence. A thorough assessment of the risk of bias and findings of individual interventions can identify rigorously designed and implemented programs that show significant effects. Prevention providers can then use these efficacious interventions within their own clinics or communities.

Since 1996, the U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) project has been conducting an on-going systematic review to identify behavioral interventions with evidence of intervention efficacy [13]. Through multiple consultations with internal and external HIV prevention researchers and methodology experts, PRS developed the Risk-Reduction Efficacy criteria to assess various sources of bias in a study’s design, implementation, analysis, and findings [14]. The PRS criteria are similar to the evaluation components used or recommended by other groups such as the Cochrane Collaboration [11], AHRQ [12], Community Guide [15], Office of Adolescent Health [16], Office of Justice’s Crime Solutions [17], and Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [18]. To ensure a reasonable level of confidence that the observed changes can be attributed to the intervention [13], interventions that meet all the study design, implementation and analysis criteria are considered low risk of bias while interventions that do not meet all of these criteria are considered high risk of bias. Interventions with low risk of bias that show significant positive intervention effects on reducing HIV risk behaviors are defined as evidence-based interventions (EBIs) and the interventions with high risk in bias, regardless of intervention effects, are defined as non-EBIs. The EBI classification approach is consistent with other systematic review efforts (e.g., Office of Adolescent Health [16], National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices [19, 20], Office of Justice’s Crime Solutions [17]) in identifying evidence-based programs and interventions.

In this systematic review, we reviewed all U.S.-based HIV risk reduction studies for PLWH available in the literature. Our goals were to describe the characteristics of the studies and interventions and to compare the similarities and differences between EBIs and non-EBIs. More specifically, we compared EBIs against two groups of non-EBIs: rigorous non-EBIs (i.e., interventions with low risk of bias but without significant positive intervention effects) and positive non-EBIs (i.e., interventions with high risk of bias but with significant positive intervention effects). These comparisons can provide helpful guidance for identifying research gaps, informing intervention development, and guiding prevention efforts.

METHODS

We used the CDC’s PRS project’s cumulative HIV/AIDS/STD prevention database [21] for identifying relevant reports (see eligibility criteria below). For the PRS database, M.M.M. and J.D. with substantial expertise in systematic searches developed and conducted a comprehensive search strategy, including automated and manual searches. The annual automated search component focused on literature published between 1988 and 2012 using the following electronic databases (and platforms): EMBASE (OVID)[22], MEDLINE (OVID)[23], PsycINFO (OVID)[24], and Sociological Abstracts (PROQUEST)[25]. For the automated search, indexing and keywords terms were cross-referenced using Boolean logic in three areas: HIV/AIDS; prevention and intervention evaluation; and behavioral or biologic outcomes related to HIV infection or transmission (e.g., unprotected sex, condom use, needle sharing, STD. No language restriction was applied to the automated search. The last automated search was conducted in January, 2013. The full search strategy of the MEDLINE database is provided in Appendix A as an example. The searches of the other databases are available from the corresponding author. The manual search included three components: (a) searches of all reports published in the previous 3 months of 36 journals (see Appendix B) to identify potentially relevant citations not yet indexed in electronic databases. The last quarterly search was conducted in January, 2013; (b) the reference lists of pertinent articles; and (c) HIV/AIDS Internet listservs (i.e., www.RobertMalow.org) and other research databases (e.g., ISI Web of Knowledge [26], RePORTER [27], Cochrane Library [28]).

Studies were included for this review if they were: (1) interventions to reduce HIV risk behavior; (2) specifically designed for PLWH; (3) conducted in the U.S.; (4) tested in controlled trials with a comparison arm; (5) measured HIV behavioral or biological outcomes (e.g., condom use, unprotected sex, number of sex partners, needle sharing, STD); (6) and published between January 1988 and December 2012. We excluded pilot studies if the full-scale efficacy trials were eligible. Linked citations, defined as publications offering additional information on the same study, were included if they provided relevant intervention evaluation information.

Pairs of trained coders independently coded each eligible intervention against the established PRS Risk-Reduction Efficacy criteria which are publically available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/dhap/prb/prs/efficacy/rr/criteria/index.html [14]. If a study did not report critical information needed to determine intervention efficacy, we contacted the primary study investigator to obtain missing information or clarification. The final efficacy determination for each study was reached by PRS team consensus.

Additionally, each eligible study was coded using a standardized coding form for the following: study characteristics (e.g., study date, location, study design, sample size, data collection method), participant characteristics (e.g., target population, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation), intervention characteristics (e.g., components, delivery method, duration, time span) and HIV risk outcomes (e.g., HIV transmission risk behavior [TRB] defined as unprotected sex with HIV-negative or serostatus unknown partners or sharing needles with HIV-negative or serostatus unknown partners, unprotected sex or condom use with any sex partners, injecting drugs, needle sharing, STD).

Eligible studies were classified into four groups based on the risk of bias and evidence of intervention effects:

EBIs: Low risk of bias with statistically significant positive intervention effects on at least one relevant HIV risk outcome

Rigorous non-EBIs: Low risk of bias without significant positive intervention effects

Positive non- EBIs: High risk of bias with statistically significant positive intervention effects on at least one relevant HIV risk outcome

Other non-EBIs: High risk of bias without significant positive intervention effects

For each of the two a-priori comparisons (i.e., EBIs vs. Rigorous non-EBIs and EBIs vs. Positive non-EBIs), we conducted Fisher’s exact tests using SPSS version 21. In the results section, we highlighted the findings if the differences between groups reached p<.05, two-sided, on Fisher’s exact tests or if the p value approached 0.10 or percentage differences between the groups were 20% or more.

RESULTS

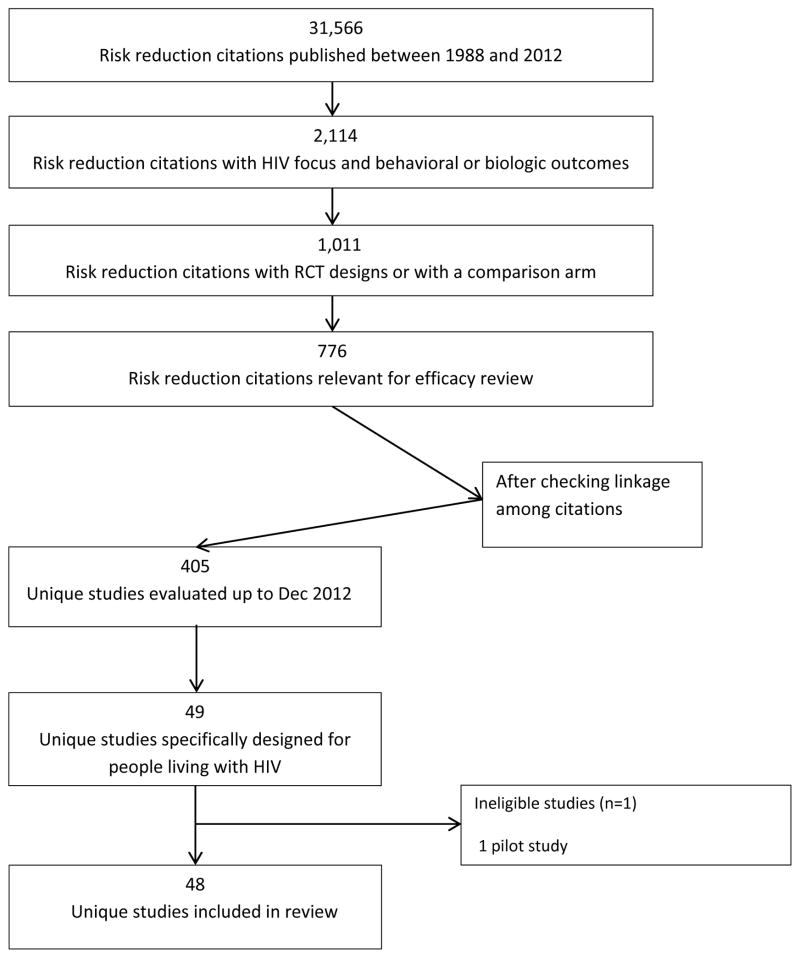

As of December 2012, PRS evaluated 405 U.S.-based risk-reduction interventions that were evaluated with a comparison group (Figure 1). Although PLWH comprise an important group in the HIV prevention effort, only 49 of 405 (12%) HIV prevention studies conducted in the United States met inclusion criteria and were specifically designed for this group. One pilot study [29] was excluded as the full-scale efficacy trial [30] was later published.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search

Overall Characteristics of Interventions for PLWH in the United States

Table 1 provides brief descriptive characteristics of the 48 included interventions [30–77] and Table 2 provides a summary of the characteristics across interventions. Among 48 studies, the majority of the studies were conducted in earlier HAART era (1996 to 2003) and later HAART era (2004 to 2012). Forty-three studies (90%) were randomized control trials (RCT). Regionally, most interventions were carried out in the West, followed by the Northeast and South. The fewest interventions were conducted in the Midwest. Not surprisingly, most of the studies were conducted in urban settings, such as Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, Milwaukee, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington DC, except one study that was conducted by phone in rural areas of 27 states.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of 48 HIV Behavioral Interventions for People Living with HIV (PLWH)

| Category | First Author [Citation Number], Study Years, Region | HIV-positive Subpopulation (Baseline Sample Size) | Study Design, Comparison Group | Intervention Name (# of sessions/ total hours), Intervention Level | Sex, Drug and Biological Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBI | El-Bassel et al. [36], 2003–2008, S, NE, W | African-American HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples (1070) | RCT, Attention control | Project EBAN (8/16), Couple |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB: (1) higher mean proportion of condom-protected sex during anal or vaginal sex at 6 months after intervention: (RR=1.22, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.41, p=.01); (2) consistent condom use during anal or vaginal sex at 6 months after intervention (RR=1.57, 95% CI: 1.27 to 1.94, p<.001) and at 12 months after intervention (RR=1.40, 95% CI: 1.13 to 1.75, p=.003); (3) lower log mean of unprotected anal or vaginal sex at 6 months after intervention (difference = −1.79, 95% CI: −2.50 to −1.08, p<.001) and at 12 months after intervention (difference = −1.15, 95% CI: −1.88 to −0.42, p=.002). No significant effect: the number of concurrent TRB partners at 6 months (RR=0.96, 95% CI=0.71 to 1.29, p=.95) and 12 months (RR=1.01, 95% CI = 0.78 to 1.30, p=.95) after intervention. Biologic outcome No significant effect on the cumulative incidence of STDs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomonas) over the 12- month assessment period (RR=0.98, 95% CI; 0.62 to 1.56., p=.93). The overall HIV seroconversion at the 12-month assessment was 5 (2 in the intervention group and 3 in the comparison group) – analysis not powered to detect difference in HIV seroconversion. |

| EBI | Fisher et al. [37], 2000–2003, NE | HIV clinic patients (497) | Non-RCT, Standard of care | Options/Opcio nes (5–10 minutes per clinic session), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB and other outcomes across the 6-, 12-, and 18-month post-baseline assessments: (1) fewer unprotected anal or vaginal TRB (b = −.28, se =.15, p=.05)a; (2) fewer unprotected anal or vaginal sex acts with any partners (b = −.38, se =.15, p=.012)a. |

| EBI | Gilbert et al. [39], 2003–2006, W | HIV clinic patients (471) | RCT, Standard of care | Positive Choice: Interactive Video Doctor (2/0.75), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: (1) less likely to report unprotected anal or vaginal sex at 3 months after the initial counseling session (RR=0.88, 95% CI = 0.773 to 0.993, p=.039) and at 3 months after the booster counseling (RR=0.80, 95% CI=0.686 to 0.941, p=.007); (2) fewer number of casual sex partners at 3 months after the booster counseling (−2.7 vs. − 0.6, p=.042). No significant effect on the absolute percent change in condom use with main partners or with casual partners at the 2 assessments (p>.05). |

| EBI | Golin et al. [40], 2006–2009, S | Sexually active adult clinic patients (490) | RCT, Attention control | Motivational Interviewing (4/4) Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB: greater reduction in unprotected anal or vaginal TRB at 4 months after intervention (b= −1.86, se= 0.92, p=.04). No significant effect on the reduction in unprotected vaginal or anal sex acts with any partners at 4 months after intervention (b= −0.71, se= 0.70, p=.32). |

| EBI | Kalichman et al. [44], 1997–1998, S | None (328) | RCT, Attention control | Healthy Relationships (5/10), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB and other outcomes: (1) fewer unprotected anal or vaginal TRB at 3 months (F=4.7, p=.03) and at 6 months (F=4.2, p=.04) after intervention; (2) fewer number of TRB partners at 6 months after intervention (OR=2.7, 95% CI NR, p=.04); (3) fewer unprotected anal or vaginal sex acts with any sex partners at 6 months after intervention (F=7.7, p=.01); (4) greater proportion of condom use during anal or vaginal sex with any partners at 6 months after intervention (F=3.8, p=.05). No significant effect on the proportion of condom use during anal or vaginal sex with non-HIV-positive partners at 3 months (p=.60) and 6 months (p=.23) after intervention. |

| EBI | Kalichman et al.[45], 2005–2009, S | None (436) | RCT, Attention control | Integrated Risk Reduction and Adherence Intervention (7/12), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB: fewer TRB at 1.5 months after intervention (Mean=0.9 [SD=5.3] vs. Mean=2.3 [SD=15.0], p <.05) and at 4.5 months after intervention (Mean=0.2 [SD=1.0] vs. Mean=1.0 [SD=3.8], p<.05). No significant effect on the number of TRB sex partners over the assessment points (p=.1). |

| EBI | McKirnan et al. [54], 2004–2006, MW | MSM (313) | RCT, Standard of care | Treatment Advocacy Program (4/9), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB: (1) decrease in the percentage of participants reporting any TRB across the 12-month assessment period (χ2 (2, N=249)=6.59, p=.037), from baseline to 4 months post-intervention (χ2 (1, N=249)= 6.57, p=.01), and from baseline to the mean of 4 and 10 months post-intervention (χ2 (1, N=249)=5.47, p=.019); (2) decrease in the mean number of TRB sex partners across the 12-month assessment period (χ2 (2, N=249)=7.16, p = .008), from baseline to 4 months post-intervention (χ2 (1, N=249)=7.01, p = .008), and from baseline to the mean of 4 and 10 months post-intervention (χ2 (1, N=249)= 6.3, p=.012). |

| EBI | NIMH et al. [31], 2000–2004, NE, MW, W | Engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (936) | RCT, Waitlist | Healthy Living Project (15/22.5), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB: greater reduction in the mean number of unprotected anal or vaginal TRB from 5–25 months post baseline (χ2=27.8, df=5; p<.0001) and 20 months post baseline (8 months after intervention) (p=.0014). |

| EBI | Richardson et al. [59], 1998–2001, W | HIV clinic patients (886) | RCT, Attention control | Partnership for Health (3–5 minutes each clinic visit), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: less likely to report unprotected anal or vaginal sex at 1 to 7 months among those who had 2 or more sex partners at baseline (OR=0.42, 95% CI=0.19 to 0.91, p=.03), among men who have sex with men with 2 more sex partners at baseline (OR=0.43, 95% CI=0.19 to 0.94, p=.04), and among those who had any casual or exchange partners at baseline (OR=0.51, 95% CI=0.27 to 0.95, p=.04). No significant effect among those who had only main partners at baseline (OR=1.31, 95% CI=0.67, 2.57, p=.44) |

| EBI | Rotheram-Borus et al. [62], 1994–1996, W, NE, S | HIV+ youth (310) | Non-RCT, Standard of care | Teens Linked to Care (31/62), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB and other outcomes at 3 months after Act Safe intervention module: (1) lower mean percentage of unprotected anal or vaginal TRB (2.8% vs. 15.5%, p < .05); (2) more likely to report no sex or 100% condom use (80% vs. 67%, p<.01). No significant effect on the number of sex partners (0.2 vs. 0.2, p value NR). |

| EBI | Rotheram-Borus et al. [63], 1999–2003, W, NE | Young substance abusers (175) | RCT, Waitlist | Choosing Life: Empowerment, Actions, Results (CLEAR) (18/36), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB and other outcomes at 15 months post baseline: Increased proportion of protected acts with all sex partners (58% vs. 22%, p<.01) and with HIV-negative partners (73% vs. 32%, p <.01). No significant effect on 100% condom use or abstinent (58% vs. 59%, p value NR). Drug outcome No significant effect on the percentage of participants injected drugs (11% vs. 20%, p value NR). |

| EBI | Sikkema et al. [67], 2002–2005, NE | With childhood sexual abuse history (247) | RCT, HIV demand control | LIFT (15/22.5) Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB and other outcomes across 4-, 8-, and 12-month assessments: fewer unprotected anal or vaginal sex acts with all partners (β=−0.233; F(1,540)=131.61; p<.001)and with HIV-negative and unknown serostatus partners (β=−0.315; F(1,221)=57.22; p<.001). |

| EBI | Wingood et al. [74], 1997–2002, S | Sexually active HIV+ female clinic patients (391) | RCT, Attention control | WILLOW (4/16), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: (1) fewer unprotected vaginal sex acts at 6 months (mean difference= −.05, p=.037) and at 12 months (mean difference= −1.3, p=.029) after intervention; (2) less likely to report never using condoms at 6 months (OR=0.3, 95% CI=0.7 to 0.9), p=.043) and 12 months (OR=0.2, 95% CI=0.5 to 0.8, p=.026) after intervention. Biologic outcome Significant positive intervention effect: less likely to acquire new bacterial STDs (chlamydia and gonorrhea) over the 12 month period (OR=0.2, 95% CI=0.1 to 0.6, p=.006). |

| EBI | Wolitski et al. [75], 2000–2002, NE, W | MSM who engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (811) | RCT, HIV demand control | Summit Enhanced Peer- Led (6/18), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB: less likely to report unprotected receptive anal TRB at 3 months after intervention (OR =0.65, 95% CI=0.44, 0.97, p<.05). No significant effect on unprotected insertive TRB (OR =0.74, 95% CI=0.48, 1.16). Biologic outcome No significant effect: STDs (syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus 1 and 2) at 6 months after intervention (test results and p value NR) |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Holstad et al. [42], 2005–2008, S | Women (203) | RCT, Attention control | Group Motivational Interviewing (8/16), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects: (1) abstinence, (2) use of condom during anal, oral, or vaginal sex during the assessment periods (baseline, 2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months)(test results and p values NR). |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Illa et al. [43], 2004–2007, S | Sexually active older clinic patients (241) | RCT, HIV demand control | Project ROADMAP (4/6), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects on TRB and other outcomes: inconsistent condom use at 6 months post baseline with the following type of partners: (1) any sex partners (7% vs. 8%, p value NR); (2) TRB partners (1.3% vs. 3%, p value NR); (3) HIV-positive partners (5% vs. 6.5%, p value NR). |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Metsch et al. [55], 2001–2003, S, W | Recently diagnosed (316) | RCT, Standard of care | ARTAS - Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study (5/NR), Individual |

Sex outcome No significant effects on TRB: unprotected anal or vaginal TRB over 12 months (OR=0.96, 95% CI=0.62 to 1.50, p=.865). |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Purcell et al. [58], 2001–2004, NE, S, W | Injection drug users (966) | RCT, HIV demand control | INSPIRE (10/20), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects on TRB: unprotected anal or vaginal TRB at (1) 3 months after intervention (OR=1.22, 95% CI=0.79, 1.89); (2) 6 months after intervention (OR=1.32, 95% CI=0.83, 2.12); (2)12 months after intervention (OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.63, 1.61). Drug outcome No significant effects on lending a needle or sharing drug paraphernalia with HIV-negative or serostatus unknown partners at (1) 3 months after intervention (OR=0.78, 95% CI=0.49, 1.25); (2) 6 months after intervention (OR=0.68, 95% CI=0.40, 1.13); (2)12 months after intervention (OR=0.77, 95% CI=0.42, 1.41). |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Safren et al. [64], 2004–2008, NE | MSM who engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (201) | RCT, Standard of care | Project Enhance (5/7.5 plus 4 boosters), Individual |

Sex outcome No significant effects on TRB: unprotected insertive or receptive anal TRB over time (baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months)(OR=0.94, 95% CI=0.78 to 1.16). |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Sorensen et al. [69], 1994–1998, W | Out of treatment substance abusers (190) | RCT, HIV demand control | Case Management (ongoing), Individual |

Sex outcome No significant effect on sex risk behaviors at 6 months after intervention (OR=0.97, 95% CI=0.54 to 1.74)b. Drug outcome No significant effect on needle-sharing behavior at 6 months after intervention (OR=0.63, 95% CI=0.35 to 1.13)b. |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Rosser et al. [61], 2005–2007, NE, S, W | MSM who engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (675) | RCT, HIV demand control | Positive Connections (1/16), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects on TRB: unprotected anal TRB, condition by time (baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months after intervention)(test results and p values NR). |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Velasquez et al. [71], 1999–2003, NR | MSM with alcohol abuse (253) | RCT, HIV demand control | Motivational Interviewing (8/NR), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects on the number of unprotected-sex days from baseline to 12 months (χ2=2.92, df=8; p=.94)a. |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Williams et al. [73], NR, NR | Heterosexual African American crack smokers (347) | RCT, Attention control | Positive Choices (6/6), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects on consistent condom use during vaginal sex, condition by time (baseline, 3 and 9 months)(F=0.61, df NR, p=.43). |

| Rigorous Non-EBI | Wolitski et al. [76], 2004–2007, MW, S, W | Homeless or at severe risk of homelessness (644) | RCT, HIV demand control | Housing Assistance & HIV Prevention (case management + 2 HIV sessions/1.25), Individual |

Sex outcome No significant effects on TRB and other outcomes: (1) unprotected anal or vaginal TRB, condition by time (baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months)(F=0.28, df NR, p=.84), (2) the number of partners, condition by time (baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months)(F=1.01, df NR, p=.39). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Chen et al. [30], 2005–2007, MW, NE, S, W | Youth with medication adherence, substance abuse or sexual risk problems (142) | RCT, Standard of care | Healthy Choices (4/6), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects from baseline to 15-month assessment: (1) increased odds of persistent low sex risk (0–2 times no condom use during study period, OR=2.71, 95% CI=1.33 to 5.52, p <.01); (2) reduced odds of high sex risk (10 or more times no condom use during study period, OR=0.41, 95% CI=0.17 to 0.99, p<.05). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Coates et al. [33], NR, W | Gay men (64) | RCT, Waitlist | Stress Reduction Training (9/NR), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effect on the number of sex partners at post intervention (mean difference=1.20, 95%CI=0.14 to 2.28, p value NR). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Cosio et al. [35], 2007–2008, MW, NE, S, W | Rural & engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (79) | RCT, HIV demand control | Telephone Motivational Interviewing (2/NR), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effect on the mean percentage of vaginal sex partners with whom condoms were used all the time at 2 months after intervention (27.1% vs. 22.5%, F=(1,77)=3.2, p<.05). No significant effect on the mean percentage of anal sex partners with whom condoms were used all the time at 2 months after intervention (20.1% vs. 19.4%, F value NR, p=.35). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Grinstead et al. [41], 1996–1998, W | Male prison inmates (123) | Non-RCT, Waitlist | Health Promotion (8/20), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effect on the percentage condom use at first sex since release (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.18–1.80)b. Drug outcome Significant positive intervention effect: Among injectors, less likely to report needle sharing at post-release (OR=0.11; 95% CI=0.03 to 0.41)b. No significant effect on the percentage of participants injected drugs since release (48% vs. 48%, p value NR). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Lightfoot et al. [48], 2001–2006, W | HIV clinic patients (529) | RCT, Waitlist | MD4 LIFE computer- delivered (11/2), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects on TRB over the 30-month post baseline period: (1) decreased the number of TRB partners (t=2.34, df=1952, P= 0.02); (2) decreased the number of unprotected anal or vaginal TRB (t= 3.23, P< 0.01). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Lovejoy et al. [49], 2009–2010, NE, MW, S | Older adults who engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (100) | RCT, Standard of care | Telephone- delivered Motivational Interviewing (4/3), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: the fewer number of unprotected anal or vaginal sex at 3 months (OR=0.32, 95% CI=0.17 to 0.56)b and 6 months (OR=0.37, 95% CI=0.2 to 0.69)b after intervention. |

| Positive Non-EBI | Margolin et al. [50], 1997–2001, NE | Injection drug users in methadone maintenance treatment (90) | RCT, HIV demand control | HHRP+ (48/minimum of 96), Group |

Sex and drug outcomes Significant positive intervention effect: less likely to engage in either unprotected sex or needle sharing or needle sharing 3 months after intervention (OR=2.96, 95% CI=1.05 to 8.36, p<.04). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Mausbach et al. [52], 1999–2005, W | Meth-using MSM who engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (341) | RCT, Attention control | EDGE (8/12), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: a greater (log) number of anal, oral and vaginal sex protected by a condom or oral dam at 5 months after intervention/8 months post baseline (t=2.13, df=283, p=.034) and at 9 months after intervention/12 months post baseline (t=2.72, df=480, p=.007). No significant effects: (1) (log) number of unprotected anal, oral, or vaginal sex (test results and p value NR); (2) ratio of total protected-to-total sex acts (test results and p value NR). |

| Positive Non-EBI | McCoy et al. [53], 1990–1992, S | Injection drug users (140) | RCT, Standard of care | Case Management Services (on- going), Individual |

Sex outcome No significant effect on the number of sex partner (multiple R=.15, p value NR) and use of condoms (multiple R=.38, p value NR) at 6 months after baseline. Drug outcome Significant intervention effect on the number of injecting partners at 6 months after baseline (multiple R=.62, p<.01) No significant effect on injecting heroin and cocaine at 6 months after baseline (multiple R=.40, p value NR). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Petry et al. [57], 2003–2008, NE | Patients with cocaine or opioid use disorders (170) | RCT, Attention control | Contingency Management (24/24), Group |

Sex and drug outcomes Significant positive intervention effects: reduced scores on the HIV Risk Behavior Scale, including risky sex and drug use behaviors, between baseline and 6 months (F(1,133)=4.75, p<.05) and baseline and 12 months (F(1,139)=5.23, p<.05). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Rose et al. [59], 2004–2006, W | HIV clinic patients who engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior(386) | RCT, Standard of care | HIV Intervention for Provider (ongoing), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: reduced the number of sex partners (OR=0.49, 95% CI=0.26 to 0.92, p<.03) at 6 months post baseline. No significant effects on TRB: (1) the number of TRB partners (OR=0.93, 95% CI=0.82, 1.69, p=.86); (2) unprotected anal or vaginal TRB (OR=1.44, 95% CI=0.90 to 2.30, p=.42). |

| Positive Non-EBI | Teti et al. [70], 2004–2008, NE | Women (184) | RCT, HIV demand control | Protect and Respect (5/7.5), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: (1) greater odds of reporting condom use during anal or vaginal sex at 6 months (OR=17.13, 95% CI=2.96, 99.10, p<.01) and at 18 months (OR=270.04, 95% CI=24.53 to 2971.94, p<.01) post baseline. |

| Positive Non-EBI | Wyatt et al. [77], NR, W | Women with histories of childhood sexual abuse (147) | RCT, HIV demand control | Enhance Sexual Health Intervention (11/1.5), Group |

Sex outcome Significant positive intervention effects: greater percentage of participants reporting vaginal sex protected by condom (OR=2.96, 95% CI NR, p=.039, one-tailed). |

| Other Non-EBI | Cleary et al. [32], 1986–1989, NE | Recently diagnosed blood donors (271) | RCT, Standard of care | Cognitive Behavioral and Skills Training Support Group (6/9), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effect on the percentage of participants reporting unprotected sex at 10.5 months after intervention (30.9% vs. 37.7%, p value NR) |

| Other Non-EBI | Coleman et al. [34], 2006–2007, NE | Older African American MSM (60) | RCT, Attention control | Social Cognitive (4/8), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects at 3 months after intervention: (1) reported consistent condom use (OR=2.04, 95% CI=0.48 to 8.77, p=.336); (2) had multiple sex partners (OR=1.43, 95% CI=0.35 to 5.79, p=.062). |

| Other Non-EBI | Fogarty et al. [38], 1993–1996, S | Women (322) | RCT, Standard of care | Women and Infants Demonstration Project (1– 24/NR), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects: (1) the odds of progressing in use of condoms with main male partner at 6–12 months (OR=1.95, p=.19) and at 12–18 months (OR=2.13, p=.13) post baseline; (2) the odds of relapsing in use of condoms with main male partner at 6–12 months (OR=0.38, p=.10) and at 12–18 months (OR=0.47, p=.15) post baseline. |

| Other Non-EBI | Kelly et al. [46], 1991, MW | Depressed Men (115) | RCT, Standard of care | Support Group (8/12), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effect on the mean number of unprotected insertive anal sex acts at 3 months after intervention (OR=0.92; 95% CI= 0.35 to 2.45, p value NR)b. |

| Other Non-EBI | Lapinski et al. [47], NR, MW | MSM (72) | Non-RCT, HIV demand control | Prevention Options for Positives (6/9), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effect on the mean score of risk reduction index at 6 weeks after intervention (1.45 vs. 1.23, p value NR). |

| Other Non-EBI | Margolin et al. [51], NR, NE | Injection drug users in methadone maintenance treatment (38) | Non-RCT, Standard of care | 3-S+ for HIV+ drug users (12/NR), Group |

Sex and drug outcomes No significant effect on the mean score of the Risk Assessment Battery assessing a range of drug- and sex-related HIV risk behaviors after intervention (0.03 vs. 0.03, p value NR). |

| Other Non-EBI | Patterson et al. [56], 1996–2001, W | Engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (387) | RCT, Attention control | Share Safer Sex (3/4.5), Individual |

Sex outcome Significant negative intervention effect on TRB at 8 months after intervention: intervention group reporting more unprotected anal, oral, and vaginal TRB (test result and p value NR). No significant effect on TRB at 12 months after intervention: the mean number of unprotected anal, oral, and vaginal TRB (OR=0.66; 95% CI=0.33 to1.33)b. Biologic outcome No significant effect on the mean number of STDs (not defined) across 12 months after intervention (test results and p value NR). |

| Other Non-EBI | Schwarcz et al. [65], 2006–2010, W | MSM engaged in HIV transmission risk behavior (411) | RCT, HIV demand control | Personalized Cognitive Counseling (2/2), Individual |

Sex outcome No significant effect on TRB: (1) mean number of unprotected anal TRB at the 12-month assessment (6 months after intervention; incident rate ratio: 0.48, 95%CI=0.12, 1.84, p=.34), (2) percentage of participants reporting unprotected anal TRB at 6 months after intervention (27.8% vs. 22.3%, p value NR). Biologic outcome No significant effect on the lab confirmed diagnosis of STD (gonorrhea or Chlamydia; test results and p value NR). |

| Other Non-EBI | Serovich et al. [66], 2005–2006, MW | MSM (77) | RCT, Waitlist | HIV-related Disclosure (4/5), Group |

Sex outcome Statistically significant negative intervention effect: intervention group had a greater odds of unprotected insertive anal sex at 3 months after intervention (OR=2.54, 95%CI NR, p<.05). No significant effect on the odds of unprotected receptive anal sex at 2 months after intervention (OR=1.55, 95% CI and p value NR). |

| Other Non-EBI | Sikkema et al. [68], 2006–2008, NE | Newly diagnosed bisexual/gay men in care (65) | RCT, Standard of care | Positive Choices (3/3), Individual |

Sex outcome No significant effects at 3 months after intervention/6 months post baseline: (1) unprotected anal or vaginal sex acts with any partners (OR=0.54, 95% CI=0.21 to 1.38)b; (2) the number of sex partners (OR=0.72, 95% CI=0.28 to 1.82)b. Biologic outcome No significant effect on STDs symptoms (not defined) at 3 months after intervention (24.1% vs. 28.6%, p value NR) |

| Other Non-EBI | Williams et al. [72], 2003–2006, W | African American, Latino MSM (137) | RCT, Attention control | Sexual Health Intervention for Men (S- HIM) (6/12), Group |

Sex outcome No significant effects: (1) the score of sex risk behavior scale, including oral, anal or vaginal sex (F (3, 130)=1.15, p=.33, condition by time interaction), (2) the number of sex partners (F(3, 129)<1, p value NR, condition by time interaction). |

Category: EBI = evidence-based interventions that show at least one significant positive intervention effect and have low risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis; Rigorous Non-EBI = interventions show no significant positive intervention effects but have low risk of bias; Positive non-EBI = interventions show at least one significant positive intervention effect but have high risk of bias; Other non-EBI = interventions show no significant positive intervention effect and have high risk of bias

Region: NE=northeast, MW=midwest, S=south, W=west

NR=not reported

TRB = HIV transmission risk behavior defined as unprotected sex with HIV-negative or serostatus unknown partners

additional info obtained from authors;

OR calculated based on descriptive data reported or provided by author

Table 2.

Percents and Medians of Select Characteristics of Evidence-Based Interventions (EBIs) and Non-EBIs

| All Interventions | EBIs | Non-EBIs | Non-EBIs by Type

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigorous |

Positive

|

Other | ||||

| k (%) | k (%) | k (%) | k (%) | k (%) | k (%) | |

| Total (% of total) | 48 | 14 (29%) | 34 (71%) | 10 (21%) | 13 (27%) | 11 (23%) |

|

| ||||||

| Conducted | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Pre-ART (1988 to 1995) | 6 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (18%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (15%) | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Early-ART (1996–2003) | 24 (50%) | 11 (79%)a,d | 13 (38%) | 3 (30%)a | 6 (46%)d | 4 (36%) |

|

| ||||||

| Later-ART (2004–2012) | 18 (38%) | 3 (21%)b | 15 (44%) | 6 (60%)b | 5 (38%) | 4 (36%) |

|

| ||||||

| >1 Study Site | 20 (42%) | 10 (71%)b,d | 10 (29%) | 5 (50%)b | 5 (38%)d | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| No Significant Positive Findings | 21 (44%) | 0 (0%)a | 21 (62%) | 10 (100%)a | 0 (0%) | 11 (100%) |

|

| ||||||

| Sources of Bias | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Small sample size | 16 (33%) | 0 (0%)c | 16 (47%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (62%)c | 8 (73%) |

|

| ||||||

| Retention | 9 (19%) | 0 (0%)c | 9 (26%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (31%)c | 5 (45%) |

|

| ||||||

| Differential attrition | 8 (17%) | 0 (0%)d | 8 (24%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (23%)d | 5 (45%) |

|

| ||||||

| Other limitations (missing data, etc) | 7 (15%) | 0 (0%)c | 7 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (38%)c | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Follow-up | 5 (10%) | 0 (0%)c | 5 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (31%)c | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| Allocation method | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Intent-to-Treat analysis | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Negative intervention effect | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Target Groupsα | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Clinic patients | 17 (35%) | 7 (50%)b | 10 (29%) | 3 (30%)b | 5 (38%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| MSM | 13 (27%) | 2 (14%) | 11 (32%) | 3 (30%) | 2 (15%) | 6 (55%) |

|

| ||||||

| Engaged in HIV transmission risk† | 11 (23%) | 3 (21%) | 8 (24%) | 2 (20%) | 4 (31%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Substance use | 10 (21%) | 1 (7%)b,d | 9 (26%) | 4 (40%)b | 4 (31%)d | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| Female | 5 (10%) | 1 (7%) | 4 (12%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (15%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| African American | 4 (8%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Depressed or childhood abuse | 4 (8%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Younger age (13 to 25 years) | 3 (6%) | 2 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Older age group (>45 years) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| Newly diagnosed | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Substance using MSM | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| Male prison inmate | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Homeless | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Rural residents | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Sample Characteristics (median)α | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Black | 50% | 48% | 54% | 63% | 51% | 37% |

|

| ||||||

| Latino | 15% | 17% | 13% | 12% | 14% | 13% |

|

| ||||||

| White | 23% | 22% | 32% | 9% | 23% | 49% |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 72% | 71% | 78% | 70% | 70% | 100% |

|

| ||||||

| Female | 27% | 28% | 27% | 29% | 37% | 36% |

|

| ||||||

| Average age (years) | 42 | 41 | 42 | 41 | 39 | |

|

| ||||||

| Comparison group | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Standard of care or Waitlist | 20 (42%) | 6 (43%)b | 14 (41%) | 2 (20%)b | 7 (54%) | 5 (45%) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-HIV Attention controlϕ | 12 (25%) | 6 (43%)b,d | 6 (18%) | 1 (10%)b | 2 (15%)d | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| HIV Demand controlȺ | 16 (33%) | 2 (14%)a | 14 (41%) | 7 (70%)a | 4 (31%) | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Power analysis reported | 20 (42%) | 8 (57%) | 12 (35%) | 5 (50%) | 5 (38%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Used ACASI for Data Collection | 20 (42%) | 9 (64%)d | 11 (32%) | 6 (60%) | 3 (23%)d | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Theory reported | 42 (88%) | 14 (100%)d | 28 (82%) | 9 (90%) | 10 (77%)d | 9 (82%) |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention Settingα | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Health Careβ | 24 (50%) | 10 (71%)b,d | 14 (41%) | 5 (50%)b | 5 (38%)d | 4 (36%) |

|

| ||||||

| Community based establishment≠ | 11 (23%) | 5 (36%) | 6 (18%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (8%) | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Public area^ | 4 (8%) | 2 (14%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (15) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Commerical+ | 2 (4%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention Level | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Individual | 21 (44%) | 7 (50%)b | 14 (41%) | 3 (30%)b | 7 (54%) | 4 (36%) |

|

| ||||||

| Group | 26 (54%) | 6 (43%)b | 20 (59%) | 7 (70%)b | 6 (46%) | 7 (64%) |

|

| ||||||

| Couple | 1 (2%) | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Delivererᶠ| ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Professional± | 28 (58%) | 7 (50%)d | 21 (62%) | 4 (40%) | 10 (77%)d | 8 (73%) |

|

| ||||||

| Counselor or health educator | 19 (40%) | 4 (29%)d | 15 (44%) | 3 (30%) | 8 (62%)d | 6 (55%) |

|

| ||||||

| Healthcare worker | 9 (19%) | 3 (21%) | 6 (18%) | 1 (10%) | 3 (23%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Peer | 13 (27%) | 4 (29%) | 9 (26%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (23%) | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Computer-based | 2 (4%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention componentsα | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Skills building | 32 (67%) | 9 (64%) | 23 (68%) | 6 (60%) | 8 (62%) | 9 (82%) |

|

| ||||||

| HIV risk reduction÷ 4 | 31 (65%) | 12 (86%)a,d | 19 (56%) | 4 (40%)a | 8 (62%)d | 7 (64%) |

|

| ||||||

| Motivation | 29 (60%) | 11 (79%)b,d | 18 (53%) | 5 (50%)b | 6 (46%)d | 7 (64%) |

|

| ||||||

| Self-efficacy | 27 (56%) | 8 (57%) | 19 (56%) | 6 (60%) | 7 (54%) | 6 (55%) |

|

| ||||||

| Serostatus disclosure | 23 (48%) | 9 (64%)d | 14 (41%) | 5 (50%) | 4 (31%)d | 5 (45%) |

|

| ||||||

| Social support | 21 (44%) | 8 (57%) | 13 (38%) | 4 (40%) | 5 (38%) | 4 (36%) |

|

| ||||||

| Personalized risk reduction plan | 21 (44%) | 8 (57%) | 13 (38%) | 4 (40%) | 6 (46%) | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Misperception about HIV | 16 (33%) | 8 (57%)b,c | 8 (24%) | 3 (30%)b | 2 (15%)c | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Personal responsibility | 16 (33%) | 5 (36%) | 11 (32%) | 2 (20%) | 6 (46%) | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Depression and anxiety | 15 (31%) | 7 (50%)b,d | 8 (24%) | 3 (30%)b | 1 (8%)d | 4 (36%) |

|

| ||||||

| Risk Screening1 | 12 (25%) | 5 (36%)b | 7 (21%) | 1 (10%)b | 5 (38%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| Medication adherence | 10 (21%) | 5 (36%)b | 5 (15%) | 1 (10%)b | 3 (23%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| Normative influence€ | 9 (19%) | 4 (29%)d | 5 (15%) | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%)d | 3 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Intimate partner violence | 4 (8%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention Intensity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 1–2 sessions | 6 (13%) | 2 (14%) | 4 (12%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (15%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||||||

| 3–10 sessions | 30 (63%) | 8 (57%)b | 22 (65%) | 8 (80%)b | 6 (46%) | 8 (73%) |

|

| ||||||

| >10 sessions | 12 (25%) | 4 (29%) | 8 (24%) | 1 (10%) | 5 (38%) | 2 (18%) |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention Time Span | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 1–3 months | 33 (69%) | 7 (50%)a | 26 (76%) | 9 (90%)a | 8 (62%) | 9 (82%) |

|

| ||||||

| > 3 months | 15 (31%) | 7 (50%) | 8 (24%) | 1 (10%) | 5 (38%) | 2 (18%) |

k = the number of interventions

EBI = evidence-based interventions that show at least one significant positive intervention effect and have low risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis

Rigorous Non-EBI = interventions show no significant positive intervention effects but have low risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis

Positive non-EBI = interventions show at least one significant positive intervention effect but have high risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis

Other non-EBI = interventions show no significant positive intervention effect and have high risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis

Significant Fisher’s Exact test between EBIs and Rigorous non-EBIs (p<0.05)

The difference between EBIs and Rigorous non-EBIs, p value approached 0.10 or the percentage differences were 20% or more

Significant Fisher’s Exact test between EBIs and Positive non-EBIs (p<0.05)

The difference between EBIs and Positive non-EBIs, p value approached 0.10 or the percentage differences were 20% or more

Not mutually exclusive

Engaged in unprotected sex with HIV-negative or serostatus unknown sex partners

Defined as a study group that receives a non-HIV intervention (e.g. general health promotion) that matched the length and doses of HIV intervention

Defined as a study group in which participants are aware of the goals of the intervention (e.g. to reduce sexual or drug use risk)

Includes HIV outpatient clinics, community health centers, hospitals, and methadone treatment clinics

Includes community-based organization, HIV/AIDS service organizations, community storefront, and drop-in center

Includes general public area (e.g., park), street location, and community gathering place

Includes adult book/video store, bar, and health club

Includes counselor, health educator and health care provider

Discussing methods to prevent HIV transmission such as abstinence, condom use, not sharing used needles

Direct or explicit attempts to change peer norms or participants’ perceptions of norms

Some studies did not report the information

The most commonly targeted groups were clinic patients [30, 37–40, 43, 48, 54, 59, 60, 62, 64, 65, 68–70, 74], followed by men who have sex with men (MSM) [33, 34, 47, 52, 54, 61, 64–66, 68, 71, 72, 75] and PLWH who engaged in TRB [31, 35, 36, 49, 52, 56, 60, 61, 64, 65, 75]. Another frequently targeted group was substance-abusing PLWH, including injection drug users [50, 53, 58], general drug users [51, 63, 69], substance-using MSM [52, 71], methamphetamine users [52], cocaine users [57], crack users [73], and alcohol abusers [71]. Fewer studies specifically targeted the following subgroups of PLWH: women [38, 42, 70, 74, 77], African Americans [34, 36, 72, 73], persons with depression or a history of childhood abuse [46, 67, 77], younger age groups (13 to 29 years) [30, 62, 63], older adults (45 years and older) [34, 43, 49], newly HIV-diagnosed persons [32, 55, 68], male prison inmates [41], and persons who were homeless or at risk of homelessness [76].

The majority of the studies (88%) reported the theoretical principles used in designing the interventions. The most commonly used theories included: Social Cognitive Theory [78], Information Motivation and Behavioral Skills (IMB) model [79, 80], Theory of Reasoned Action, Social Action Theory [81], Motivational Interviewing [82], Transtheoretical Model of Stage of Change [83], and Theory of Gender and Power [84]. Half of the interventions were conducted in healthcare settings, such as HIV outpatient clinics, community health centers, hospitals, or methadone treatment clinics. More than half of the interventions were delivered by professionals such as healthcare providers (19%), counselors or health educators (40%). Some were delivered by peers (27%). Two were computer-delivered interventions using interactive video doctors [39, 48]. The majority of the interventions consisted of 3 to 10 sessions (63%) and lasted 1 to 3 months (69%). The median time per session was 90 minutes, ranging from 3–5 minutes to 3 hours.

The most commonly reported outcomes (see Table 3) were TRB (21 studies) and unprotected sex behavior (partner serostatus not reported, 33 studies). About half of the studies that reported these two outcomes showed significant positive intervention effects (12 studies and 16 studies, respectively). There were fewer studies that reported injection drug use or needle sharing behaviors (5 studies). Additional three studies combined with sex and drug behaviors in a risk index. About half of these studies showed significant positive intervention effects. All the sex and drug use behaviors were based on self-report. Regarding biologic outcomes, only one study out of six studies that measured STD (lab confirmed or doctor’s diagnosis) showed a significant positive intervention effect.

Table 3.

Summary of Outcome Measures and Findings by Groups

| Outcomes and Findings1 | Total (48 studies) | EBIs (14 studies) | Rigorous Non-EBIs (10 studies) | Positive Non-EBIs (13 studies) | Other Non-EBIs (11 studies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Risk Behavior (i.e., unprotected sex with HIV-negative or serostatus unknown partners) | |||||

| # of studies reported the outcome | 21 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| # of studies showed significant positive intervention effects | 12 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Unprotected Sex Behavior (partner serostaturs not reported) | |||||

| # of studies reported the outcome | 33 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 8 |

| # of studies showed significant positive intervention effects | 16 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Sex and Drug Combined Index | |||||

| # of studies reported the outcome | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| # of studies showed significant positive intervention effects | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Injection Drug Use or Needle Sharing | |||||

| # of studies reported the outcome | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| # of studies showed significant positive intervention effects | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Biologic Outcome (i.e., Sexually Transmitted Diseases) | |||||

| # of studies reported the outcome | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| # of studies showed significant positive intervention effects | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

EBI = evidence-based interventions that show at least one significant positive intervention effect and have low risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis Rigorous Non-EBI = interventions show no significant positive intervention effects but have low risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis Positive non-EBI = interventions show at least one significant positive intervention effect but have high risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis Other non-EBI = interventions show no significant positive intervention effect and have high risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis

A study may contribute to more than one outcome measure

Classification of EBIs and Non-EBIs Based on the Risk of Bias and Significant Positive Intervention Effects

Of the 48 included studies, 24 interventions (50%) had low risk of bias. Among these, 14 were EBIs that also showed significant positive intervention effects [31, 36, 37, 39, 40, 44, 45, 54, 59, 62, 63, 67, 74, 75] and the other 10 interventions were Rigorous non-EBIs [42, 43, 55, 58, 61, 64, 69, 71, 73, 76]. Twenty-four interventions had high risk of bias, including 13 Positive non-EBIs [30, 33, 35, 41, 48–50, 52, 53, 57, 60, 70, 77] and 11 Other non-EBIs [32, 34, 38, 46, 47, 51, 56, 65, 66, 68, 72]. Eighteen Positive and Other non-EBIs (75%) had multiple sources of bias. The common sources of bias included: analytic sample sizes less than 40 per arm, less than a 60% retention rate of study participants per arm, greater than 10% differential attrition between arms, substantial missing data, not conducting intent-to-treat analysis, or significant negative findings. Another way of looking at the breakdown of 34 non-EBIs is that 21 interventions (61%) did not find any significant positive intervention effects.

Comparisons between EBIs and Rigorous Non-EBIs

Table 2 and Table 3 show comparisons between EBIs and rigorous non-EBIs. The two groups were similar in terms of target populations (i.e., MSM, those who engaged in HIV transmission risk), sample characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity, gender, age), reporting of power analysis and theories, use of ACASI for data collection, several intervention components (i.e., self-efficacy, skills building, serostatus disclosure, social support, personalized risk reduction plan, personal responsibility, normative influence, intimate partner violence), and type of outcomes reported (e.g., TRB, unprotected sex behavior, injection drug use or needle sharing).

Despite the similarities, EBIs and Rigorous non-EBIs differed in a few ways. More EBIs than Rigorous non-EBIs were evaluated in the earlier HAART era (1996–2003), carried out at multiple study locations, targeted clinic patients, delivered to individuals, conducted in healthcare settings, used standard of care or non-HIV attention controls (defined as receiving non-HIV intervention such as general health promotion that matched length and doses of HIV-intervention) as comparison groups. There was a higher percentage of EBIs than non-EBIs that addressed the following intervention components: discussing HIV risk-reduction, promoting motivation for behavioral change, addressing misperception about HIV, reducing negative affect such as depression or anxiety, enhancing medication adherence, and conducting risk screening to guide prevention messages. In contrast, more Rigorous non-EBIs were conducted in the later-ART era, targeted substance users, used HIV demand controls as comparisons (defined as participants in the comparison group are aware of the intervention they received were intended to change their sex or drug use risk), and had 3 to 12 intervention sessions over a period of 1 to 3 months

Comparison between EBIs and Positive Non-EBIs

There were several similarities between EBIs and Positive non-EBIs. Comparable percentages of EBIs and positive non-EBIs were observed on the following: intervention level (i.e., individual, group, couple), intervention intensity and time span, and some intervention components (e.g., building skills and self-efficacy, conducting risk screening to guide personalized prevention messages, working with participants on personalized risk-reduction plans, emphasizing personal responsibility to take care of one’s and partner’s health, and addressing medication adherence issues). However, Positive non-EBIs were more likely to be small-scale studies conducted with subgroups of PLWH (e.g., rural areas, depressed MSM, meth-using MSM, injection drug users, substance users, women) compared to EBIs. Positive non-EBIs were less often conducted as multi-site studies and in health care settings or community-based establishments in contrast to EBIs. Positive non-EBIs were also less likely than EBIs to use non-HIV attention controls, use ACASI for data collection, report theories, and report and show positive intervention effects on TRB.

Highlights of EBIs

While the comparisons between EBIs and two non-EBIs groups (i.e., Rigorous and Positive) can inform research gaps and future intervention development, a closer examination of the EBIs can provide helpful direction for providers in healthcare and non-healthcare settings in selecting model programs suitable for their target populations. More than half of EBIs targeted HIV clinic patients [37, 39, 40, 54, 59, 62, 74], but none targeted newly diagnosed PLWH. Six EBIs targeted specific subgroups of PLWH: MSM [54, 75], heterosexual African American discordant couples [36], substance using youth and young adults [63], women [74], and PLWH with a history of childhood sexual abuse [67]. All 14 EBIs had greater than 50% ethnic minority participants (range: 53% to 100%), seven of which included a majority of African Americans. The key components of EBIs included addressing HIV risk reduction behaviors, motivation for behavioral change, misconception about HIV, and issues related to mental health, medication adherence, and HIV transmission risk behavior.

A variety of intervention delivery methods, ranging from brief prevention messages delivered during regular HIV care visits to intensive multi-session interventions over several weeks or months, were shown to be successful in reducing TRB as well as unprotected sex with any sex partners. Three EBIs were brief interventions. In one intervention, the healthcare provider delivered 3- to 5-minute prevention messages that focused on self-protection, partner protection, and disclosure. Posters and patient education brochures in the clinics reinforced provider-delivered prevention messages [59]. Another intervention used clinicians to deliver the 5- to 10-minute tailored prevention message based on risk screening information that patients provided [37]. In the third intervention, patients completed a computer-based risk assessment and then viewed a 24-minute video clip in which an actor-portrayed physician delivered risk-reduction messages tailored to the patient’s unique risks. At the conclusion of the video section, patients received an educational worksheet for self-reflection, harm reduction tips, and local resources and clinicians received a cueing sheet that summarized patient’s risk profile and suggested counseling statements [39].

Intensive behavioral risk-reduction interventions (defined as multiple sessions over weeks and months with a median of 90 minutes per session) in healthcare [40, 54, 62, 74] and non-healthcare settings [31, 36, 44, 45, 63, 67, 75] can also lead to reductions in risky sexual behaviors among PLWH. In 11 EBIs, peer-educators [44, 54, 74, 75] or health educators/counselors [31, 36, 40, 45, 62, 63, 67] provided multi-session interventions to individual PLWH [31, 40, 54, 63], small groups of adult PLWH [44, 45, 62, 67, 74, 75], or discordant couples with HIV [36] with varied demographic characteristics. Interactive sessions focused on many topics such as coping with an HIV diagnosis, addressing serostatus disclosure, building condom use skills, negotiating safe sex behaviors, avoiding risky drug use, or medication adherence. Participants of all 11 EBIs were significantly less likely to report TRB or unprotected sex with any partners at some point within 3 to 12 months after interventions.

DISCUSSION

Given the importance of reducing risk behaviors among PLWH for preventing new HIV infection and STDs, it is encouraging to have identified 14 EBIs that had low risk of bias and showed significant positive intervention effects on reducing HIV risk behavior, especially for reducing TRB. These interventions can serve as model programs for providers in healthcare and non-healthcare settings seeking EBIs best suited for their target populations.

Brief Interventions in Healthcare Settings

The healthcare setting affords a great opportunity to integrate behavioral prevention with routine medical care and address behavior change over time. Consistent with a previous meta-analysis [8], we found two EBIs that showed brief prevention counseling messages (e.g., 3 to 10 minutes) delivered by healthcare providers during routine HIV care visits can lead to significant reductions in HIV transmission risk among PLWH. This brief provider-delivered risk-reduction approach has been implemented and evaluated in two large-scale demonstration projects [86, 87]. Both studies showed the feasibility of conducting brief provider-delivered risk-reduction interventions in busy healthcare settings and the effectiveness of this approach in reducing HIV transmission risk behaviors of PLWH. Based on the body of evidence, the brief provider-delivered risk-reduction intervention during HIV patient’s routine care visits has been recommended and currently promoted to be standard of HIV clinic care by CDC (i.e., Prevention IS Care [88]).

The importance of clinic provider’s role in facilitating healthier behaviors of patients is not new. However, evidence suggests that providers are not consistently talking to patients about safer sex, injection drug use, and HIV prevention methods. Approximately 23% to 29% of HIV patients reported that their providers have never talked to them about safer sex [89, 90]. The data on provider-patient communication in the most recent HIV primary care visit showed that 65% of HIV-seropositive injection drug users reported having discussed HIV prevention with their provider [91] and 53% of Ryan White CARE Act patients from 9 states reported having discussed safer sex and HIV prevention methods with their providers [92]. These percentages are similar to the percentages reported by healthcare providers [93]. Studies also showed that providers were more likely to provide prevention counseling to new patients rather than established patients [93, 94]. These findings highlight considerable room to increase the delivery of brief prevention counseling by providers during routine HIV care visits, especially among returning patients.

Published studies in the literature indicate several common barriers to providing risk screening and risk reduction interventions in healthcare setting, including lack of time, competing priorities, limited staffing, providers’ lack of risk-reduction counseling skills, discomfort with talking about risk behaviors, and the belief that interventions will not change behavior [92, 93, 95–99]. However, evidence suggests that training on brief risk screening methods requires minimal time and training on brief risk-reduction interventions enhances the provider’s comfort, skill, efficiency, and motivation [60, 94, 96, 99]. Providers are more likely to engage in risk-reduction prevention counseling if other providers in the same clinics are also providing prevention counseling. Additionally, providers who agree that risk-reduction prevention is part of the clinic’s mission are more likely to conduct counseling to HIV patients [94]. Innovative approaches are needed to prepare and support providers for delivering more consistent risk-reduction interventions to their HIV patients. Some approaches to consider include integrating behavioral prevention into the clinic mission, providing training to enhance the provider’s ability, motivation, and comfort to deliver brief preventions, reimbursing counseling time, and educating medical students about HIV prevention.

More Intensive, Multi-session Interventions in Healthcare and Non-Healthcare Settings

Our systematic review also found that longer and multi-session HIV interventions are efficacious in changing HIV transmission risk behaviors of PLWH. The feasibility of delivering interventions with multiple sessions over time is not clear, especially in busy clinic facilities. However, these interventions are not without merit because some PLWH require additional help to address multiple interconnected factors (e.g., substance use, depression, childhood sexual abuse, interpersonal and partner dynamics) underlying their risk behaviors. Several intensive EBIs are successful in reducing risk behaviors among PLWH at high risk of transmitting HIV. Referrals for evidence-based, multi-session risk-reduction interventions for PLWH who report high levels of risk or continue risk behaviors may be a beneficial component of comprehensive HIV prevention efforts at the clinic/agency, state, and federal levels. Creating directories of local clinics or agencies that offer evidence-based, intensive risk-reduction interventions, facilitating the collaboration between clinic and community providers, and establishing policies and procedures regarding patient’s referrals to intensive interventions can also be helpful to ensure the services are in place as needed [100].

Considerations for Future PLWH Interventions

While our review identified several EBIs for healthcare and non-healthcare settings, the dissemination of the interventions remains limited as these settings often do not have the human or financial resources to devote to interventions. One potential solution is the use of new technologies. Computer-based interventions are shown to be efficacious in increasing condom use and reducing sexual activity, numbers of sexual partners, and incident STD [101]. The advantages include greater intervention fidelity, lower delivery costs, and greater flexibility in dissemination channels such as in person, by mail, on the webs, through cell phones [101]. Several computer-based interventions that address HIV risk behavior as well as mediation adherence and other issues (e.g., retention, treatment readiness) for PLWH are on the way (e.g., CDC and NIH funded comprehensive prevention with positive project, CDC funded computer-based Interactive Screening and Counseling Tool, CBISCT). More research is needed to explore the best way to incorporate new technologies to deliver HIV behavioral interventions that address the prevention needs of PLWH.

Several identified differences and similarities between EBIs and the two groups of non-EBIs (i.e., Rigorous and Positive) can inform the design and testing of future behavioral interventions for PLWH. EBIs tended to target HIV clinic patients whereas more of the two non-EBIs groups targeted specific high-risk populations (e.g., substance-using MSM, IDUs, substance abusers, sexual actively older adults, inmates, homeless) or understudied populations (e.g., rural residents, newly diagnosed).

When comparing EBIs and Rigorous non-EBIs, there were many more similarities than differences in study design, implementation and analysis, outcome measures, and intervention components. One unique difference is that EBIs were more likely to use standard of care or non-HIV attention control and less likely to use HIV demand controls. For HIV-related comparison groups, using variations of the interventions as comparison groups may greatly reduce the ability to detect intervention effects [102]. Using a standardized comparison arm that the HIV prevention field could agree upon as a prevention standard can facilitate comparing intervention effects across studies.

Unsurprisingly, when comparing EBIs and Positive non-EBIs, there were obvious differences in the sources of bias. More positive non-EBIs than EBIs were small sample size studies intended as pilot studies to test the feasibility of the intervention implementation. Several of non-EBIs also suffered from substantial attrition, differential retention, and missing data issues. While positive non-EBIs showed at least one significant positive finding on sex or injection drug use outcomes, few reported and found significant positive findings on TRB. Positive non-EBIs are good candidates for further evaluation and they should be evaluated with more rigorous methods that reduce the risk of bias in study design, implementation and analysis and that measure HIV transmission risk behavior.

Limitations

The findings of our review must be viewed within the context of the limitations of the available evidence. First, although the majority of the studies were RCTs, many were un-blinded and relied on self-reported sexual behavior, which may open to social desirability bias [103]. Given that blinded trials are not feasible in HIV behavioral prevention research, future intervention trials should consider complementing self-reported behavioral measures with biologic outcomes such as STD to assess intervention efficacy [104]. There were very few studies in the current literature that measured both behavioral and biologic outcomes. Second, while the majority of EBIs demonstrated significant positive intervention effects on reducing unprotected sex with HIV-negative and serostatus unknown partners, it is unclear how the observed behavioral changes may translate into averted new infections. Many factors such as individual’s viral load level, type of sex acts, and present of other STD may affect the probability of new HIV transmission. Although the complexity of the multiple influencing factors that could affect HIV transmission potential makes it impossible to estimate the number of new infections averted by the interventions reviewed here, our findings showed that some interventions are more successful than others in promoting positive behavior changes that are important factors in HIV transmission risk.

In addition, there are several limitations specific to this review that merit consideration when interpreting the findings. First, we classified all the U.S.-based interventions for PLWH into EBIs vs. non-EBIs based on the risk of bias and evidence of positive intervention effects. While this classification approach is intended to identify model programs, it differs from meta-analytic approaches, which provide the overall estimate of the intervention effects. Second, although we contacted primary investigators to confirm our evaluation of the risk of bias and intervention effects, the coding of study and intervention characteristics are based on published reports that may not provide complete information about the intervention. Third, our review relied on the published literature and our findings might be susceptible to for publication bias. Fourth, while we observed some patterns that may explain differences among EBIs and non-EBIs, there are multiple factors that may contribute to an intervention’s lack of evidence and it is difficult to disentangle a specific reason or combination of reasons.

CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations, our findings also offer several implications for research and HIV prevention. Moving evidence-based prevention for PLWH into practice is an important step in making a greater impact on the HIV epidemic. Our systematic review identified several EBIs that can serve as model programs for providers in healthcare and non-healthcare settings who are looking to implement evidence-based interventions best suited for the populations they serve. The differences between EBIs and non-EBIs identified in this review point out that more EBIs are needed for the subgroups of PLWH such as substance-using MSM, injection drug users, sexually active older adults, inmates, homeless persons, rural residents and newly diagnosed persons. Healthcare settings where PLWH receive routine HIV medical care and other services continue to be an ideal setting to deliver behavioral interventions. Clinics and public health agencies at the state, local, and federal levels can use the results of this review as a resource when making decisions that meet the needs of PLWH to achieve the greatest impact on the HIV epidemic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Prevention Research Branch, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and was not funded by any other organization.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authorship: N.C. conceptualized the review, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.M.M. and J.D. undertook the comprehensive literature search. All authors did coding, provided technical and material support, and involved in manuscript review and editing. N.C. has full access to all the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Reference List

- 1.CDC. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data - United States and 6 dependent area, 2011. [Accessed 15 November 2013];HIV Surveillance Report. 2013 18 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance. Published October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Suveillance Supplemental Report. [Accessed 11 April 2013];HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012 17(4) http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010supp_vol17no4/. Published December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallabhaneni S, McConnell JJ, Loeb L, Hartogensis W, Hecht FM, Grant RM, et al. Changes in seroadaptive practices from before to after diagnosis of recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair JM, McNaghten AD, Frazier EL, Skarbinski J, Huang P, Heffelfinger JD. Clinical and Behavioral Characteristics of Adults Receiving Medical Care for HIV Infection --- Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crepaz N, Marks G, Liau A, Mullins MM, Aupont LW, Marshall KJ, et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-diagnosed MSM in the United States: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:1617–1629. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832effae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Washington, DC: Office of National AIDS Policy; [Accessed 4 February 2013]. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf. Published July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20:143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:642–650. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy CE, Medley AM, Sweat MD, O’Reilly KR. Behavioural interventions for HIV positive prevention in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:615–623. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Handbook; 2011. Chapter 8: Assessing the risk of bias in included studies. www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Sep, 2013. AHRQ Publication No.10(13)-EHC063-EF. Chapters available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Project. [Accessed 15 April 2013];HIV Risk Reduction Efficacy Review: Efficacy Criteria. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/efficacy_criteria.htm.

- 15. [Accessed 15 April 2013];The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide) http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html.

- 16.U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Adolescent Health. [Accessed 4 February 2013];Teen Pregnancy Prevention: Evidence-Based Programs. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/oah-initiatives/tpp/tpp-database.html.

- 17.U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Crime Solutions. [Accessed 4 February 2013]; http://www.crimesolutions.gov/

- 18.Grade of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group. [Accessed 15 April 2013]; http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/index.htm.