Abstract

Piperine (PIP) is used as anticonvulsant in traditional Chinese medicine. Co-administration of low-dose sodium valproate with PIP has been regarded to have potential anticonvulsant activity.

Aim:

This study was intended to investigate the effect of PIP on the pharmacokinetics of sodium valproate (SVP) in the plasma samples of rats using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) method.

Materials and Methods:

The plasma samples obtained after oral administration of SVP, 150 mg/kg and SVP, 150 mg/kg + PIP, and 5 mg/kg to male Wistar rats were used to quantify the concentrations in plasma using GC-MS method.

Results:

A simple and accurate method developed in-house was applied for the analysis of plasma samples of Wistar rats after oral administration of SVP and PIP + sodium valproate, respectively. The pharmacokinetic parameters reported 14.8-fold increase in plasma concentration (maximum observed concentration in the concentration-time profile), 4.6-fold increase in area under the curve and slightly prolonged time to reach that concentration (1 h) of SVP in presence of PIP.

Conclusion:

The study reaffirms the bioenhancing effect of PIP suggesting possibility of dose reduction of SVP while co-adminstering with PIP.

KEY WORDS: Anticonvulsant, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, piperine, sodium valproate

Sodium valproate (SVP) is a well-established, broad spectrum anti-convulsant drug. SVP acts by altering the activity of the neurotransmitters, gamma amino butyrate and N-methyl-D-aspartate.[1] Moreover, SVP blocks Na+ channels, Ca2+ channels, and voltage-gated K+ channels.[2]

Piperine (PIP) is an alkaloid obtained from Piper longum (Piperaceae). The potential of PIP as anticonvulsant, however, was discovered in China. Antiepilepserine, one of the derivatives of PIP, is used as an antiepileptic drug in treating different types of epilepsy in China.[3]

SVP is a drug with narrow therapeutic index,[4] therefore, drug monitoring becomes inevitable. PIP is a powerful herbal bioenhancer that is known to exert its effects by improving absorption, inhibition of microsomal enzymes in the gut and liver or through inhibition of efflux pumps in the gut and liver.[5] Therefore, co-administration of SVP with PIP requires thorough evaluation of their pharmacokinetic interaction through determination of plasma concentrations using suitable analytical method.

Several analytical methods are available for the plasma and serum quantification of SVP and PIP individually. However, Gas chromatography (GC) is considered to be the method of choice, owing to the volatile nature of SVP.[6]

In the present work, an effort has been made to study the effect of PIP on the pharmacokinetics of SVP, in rat plasma.

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents

SVP and PIP were procured from Sigma (Mt Louis, USA). Ethyl acetate and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-Na were obtained from CDH (New Delhi). LCMS grade methanol and hydrochloric acid were purchased from SDFCL (Mumbai). Inert helium gas was obtained from Sigma gas and services (New Delhi). Other chemicals used were of analytical grade obtained from commercial sources.

Animal handling

The animals used in the in vivo experiments were male Wistar rats (10–12 weeks old of 180–250 g). The rats were approved from Jamia Hamdard Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, New Delhi (Registration No. 173/CPCSEA) and procured from the Central Animal House Facility, Hamdard University, New Delhi. They were housed in polypropylene cages, maintained at 21 ± 1°C and 55 ± 5% relative humidity with a 12 h light/dark cycle, with free access to standard laboratory diet (Lipton feed) and water ad libitum.

The in vivo study was conducted to determine the pharmacokinetic profile of SVP after co-administration with PIP. The rats were divided into two groups each containing seven animals. The plasma profiles were compared after oral administration of SVP and sodium valproate + suspension of PIP (0.1% w/v carboxy methyl cellulose).

Pharmacokinetic study

Formulations (SVP, 150 mg/kg and SVP, 150 mg/kg + PIP, 5 mg/kg) were administered orally using oral feeding needle. The rats were anesthetized with diethyl ether, and blood samples (0.5 mL) were withdrawn from the tail vein of rat at 0 (predose), 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h in microcentrifuge tubes containing EDTA (1.5 mg/mL). The blood collected was mixed properly with the anticoagulant and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min. The plasma was separated and stored at −21°C until drug analysis was carried out using the in-house developed and validated GC-mass spectrometry method.

The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated based on a noncompartmental model. Peak plasma concentration (maximum observed concentration in the concentration-time profile [Cmax]), time of peak concentration time to reach that concentration (tmax) was obtained directly from the plasma concentration-time curve, whereas area under the curve (AUC) from time 0 to time t (AUC0-t) and area under the first moment curve (area under first moment curve0-∞) were calculated using trapezoidal method.

Development of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry method for simultaneous analysis of sodium valproate and piperine

Agilent 7890A series, Germany system equipped with split-splitless injector and CTC-PAL autosampler was used for analysis of the standard and plasma samples. Apolar HP-5MS (5% phenyl polymethylsiloxane) capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. and 0.25 μm film thickness) fitted to a mass detector was used as stationary phase. Carrier gas (Helium), used as mobile phase and the flow rate, was 1.5 mL/min for first 7 min followed by 2.5 mL/min for next 6 min, splitless. The injector temperature was maintained at 260°C, detector temperature at 300°C, while column temperature was kept at 70°C for 3 min, followed by 180°C for 3–6 min (at a rate of 35°C/min), then at 280°C for 6–8 min (at a rate of 50°C) and then kept at hold for 4 min. The transfer line was heated at 280°C. Mass spectra were acquired in electron ionization mode (70 eV) in m/z range 30–600. The peaks of the standard were identified by comparison of their mass spectra to those from NIST/NBS libraries, using different search engines. The detection limit was 1.8 µg/mL for SVP and 3.0 µg/mL for PIP.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation of pharmacokinetic data was performed using one-way analysis of variance. Data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) of separate experiments (n = 7). Statistically significant differences were assumed when P < 0.05. All values are expressed as their mean ± SD.

Results and Discussion

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry method for simultaneous analysis of sodium valproate and piperine

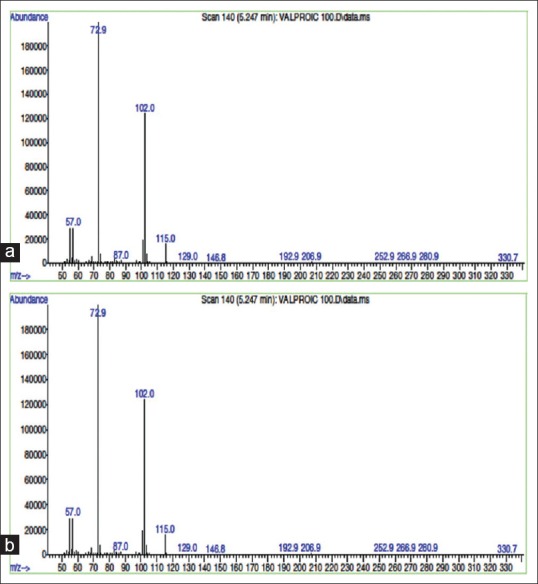

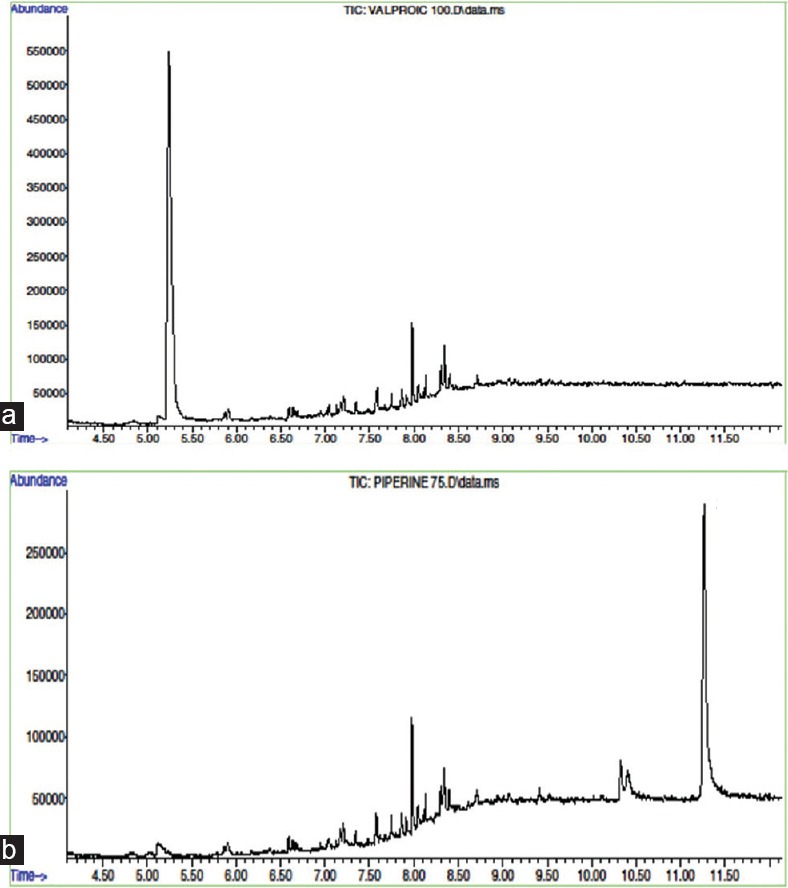

SVP and PIP are low molecular weight compounds with favorable sensitivity in electric ionization mode detection using mass detector. The mass spectrum of SVP showed selected reaction monitoring transition from m/z 101.9 to m/z 72.9 [Figure 1a] and from m/z 280.9 to m/z 206.9 in PIP [Figure 1b]. The retention times (RT) for SVP and PIP were 5.2 min and 11.2 min, respectively [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Mass spectrum of sodium valproate showing selected reaction monitoring transition from m/z 101.9 to m/z 72.9. (b) Mass spectrum of piperine showing selected reaction monitoring transition from m/z 280.9 to m/z 206.9

Figure 2.

Total ion chromatogram of 100 μg/mL of (a) sodium valproate and (b) piperine, showing retention times at 5.3 min and 11.2 min, respectively

In vivo pharmacokinetic study

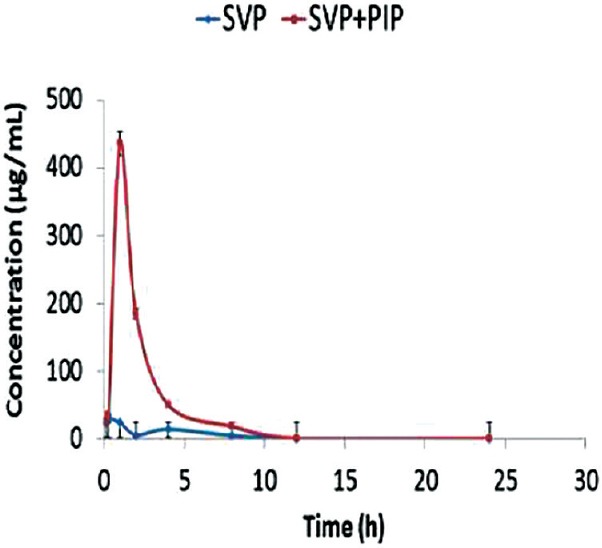

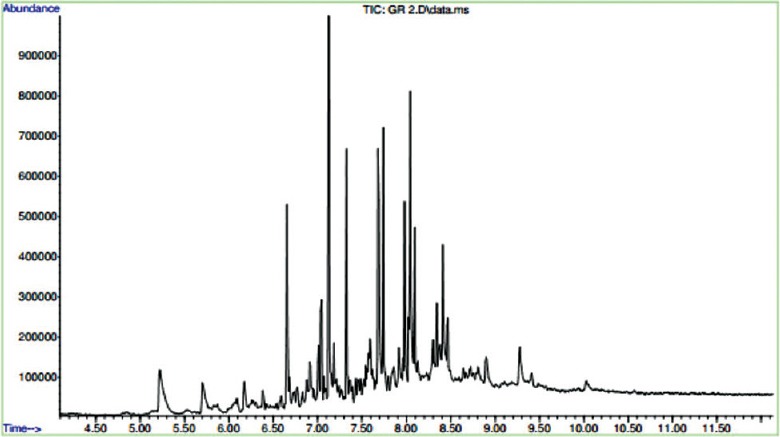

The pharmacokinetic in vivo study was carried out to quantify the effect of PIP on plasma concentrations of SVP after oral administration of SVP and PIP as shown in Figure 3. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by noncompartmental analysis also called as model independent analysis. All pharmacokinetic parameters (tmax, Cmax, AUC0-t etc.) were calculated individually for each subject in the group, and the values were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 7). The plasma concentration profile of SVP with PIP represents greater improvement of drug absorption than the SVP alone. It was observed that the plasma concentration of SVP increased 14.8-fold on administration of SVP with PIP [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Plasma concentration profile of sodium valproate with and without oral administration of piperine to adult male Wistar rats. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 7)

Figure 4.

Total ion chromatogram of sodium valproate (150 mg/kg) + piperine (5 mg/kg) in rat plasma

Peak concentration (Cmax) and time of peak concentration (tmax) were obtained directly from the individual plasma concentration-time profiles. The AUC determines the bioavailability of the drug for the given dose. The relative bioavailability was calculated as:

Frel = (AUCSVP + PIP/AUCSVP) ×100%.

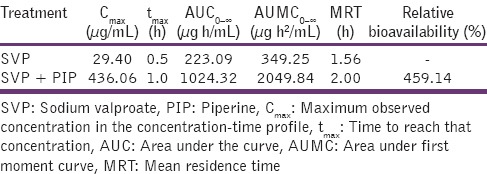

The oral pharmacokinetic parameters are listed in Table 1. The Cmax of SVP + PIP group was significantly higher (P < 0.01) than that obtained with SVP alone. There was 4.6-fold increase in the AUC of SVP + PIP compared with SVP alone. The tmax of SVP in the presence of PIP was significantly increased than that of SVP alone indicating that the co-administration of PIP with SVP prolongs the time course of action.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for SVP and SVP + PIP after oral administration to albino Wistar rats

The benefits of adding a bioenhancer include reduced drug dosage, reduced cost of the drug, reduced incidence of drug resistance, and reduced risk of adverse drug reaction/side effects. Moreover, efficacy is enhanced by increased bioavailability. With the discovery of the first bioavailability enhancer PIP in 1979, a new class of drug and a new concept were introduced into science. This revolutionary discovery opened up a new field that of increasing drug bioavailability.[7]

PIP can potentiate the efficacy of drugs by altering the drug levels.[8] Further research on several[9] classes of drugs including antitubercular, leprosy, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cardiovascular system, and central nervous system drugs showed similar results. PIP was found to increase bioavailability of different drugs ranging from 30% to 200%. Subsequent research has shown that it increases curcumin bioavailability by almost 10-fold.[10] PIP increases AUC of phenytoin, propranolol, and theophylline in healthy volunteers and plasma concentrations of rifampicin in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.[11] A lot of research is being carried out on PIP and its bioenhancing effect on various modern medicines.

The several natural compounds other than PIP with bioenhancing properties, such as, quercetin, genistein, glycyrrhizin, etc., are being isolated for their possible use along with modern medicines.

Conclusion

The oral bioavailability of SVP was increased in the presence of PIP and 4.6-fold increase was observed in AUC of SVP. From the results, one can conclude that PIP is a bioavailability enhancing agent as it enhances bioavailability of various drugs and nutrients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chateauvieux S, Morceau F, Dicato M, Diederich M. Molecular and therapeutic potential and toxicity of valproic acid. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010. 2010:pii–479364. doi: 10.1155/2010/479364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macdonald RL, Kelly KM. Antiepileptic drug mechanisms of action. Epilepsia. 1995;36(Suppl 2):S2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb05996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pei YQ. A review of pharmacology and clinical use of piperine and its derivatives. Epilepsia. 1983;24:177–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1983.tb04877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isbister GK, Balit CR, Whyte IM, Dawson A. Valproate overdose: A comparative cohort study of self poisonings. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:398–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umesh KP, Amrit S, Anup KC. Role of piperine as a bioavailability enhancer. Int J Recent Adv Pharm Res. 2011;4:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang J, Park YS, Kim SH, Kim SH, Jun MY. Modern methods for analysis of antiepileptic drugs in the biological fluids for pharmacokinetics, bioequivalence and therapeutic drug monitoring. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;15:67–81. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2011.15.2.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atal CK. A breakthrough in drug bioavailability – A clue from age old wisdom of Ayurveda. IDMA Bull. 1979;10:4834. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johri RK, Zutshi U. An Ayurvedic formulation ‘Trikatu’ and its constituents. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;37:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zutshi RK, Singh R, Zutshi U, Johri RK, Atal CK. Influence of piperine on rifampicin blood levels in patients of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 1985;33:223–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaikh J, Ankola DD, Beniwal V, Singh D, Kumar MN. Nanoparticle encapsulation improves oral bioavailability of curcumin by at least 9-fold when compared to curcumin administered with piperine as absorption enhancer. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2009;37:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Z, Yang X, Ho PC, Chan SY, Heng PW, Chan E, et al. Herb-drug interactions: A literature review. Drugs. 2005;65:1239–82. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]