Significance

The present study is, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of the molecular mechanisms underlying the association of IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) expression with milder clinical manifestations of systemic sclerosis (SSc). It is speculated that endogenous ligands induce Toll-like receptor 4 signaling and promote IRF5 transcriptional regulation of its target gene promoters, which may be required for the development of SSc. Our present study supports this notion. Symptoms associated with SSc in humans were suppressed in mice deficient in the Irf5 gene. As such, this study offers previously unidentified insight into the complexity of SSc pathology, giving impetus to further clinical studies for the treatment of the disease.

Keywords: interferon regulatory factor 5, systemic sclerosis, fibrosis, vasculopathy, Toll-like receptor 4

Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multisystem autoimmune disorder with clinical manifestations resulting from tissue fibrosis and extensive vasculopathy. A potential disease susceptibility gene for SSc is IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), whose SNP is associated with milder clinical manifestations; however, the underlying mechanisms of this association remain elusive. In this study we examined IRF5-deficient (Irf5−/−) mice in the bleomycin-treated SSc murine model. We show that dermal and pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin is attenuated in Irf5−/− mice. Interestingly, we find that multiple SSc-associated events, such as fibroblast activation, inflammatory cell infiltration, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, vascular destabilization, Th2/Th17 skewed immune polarization, and B-cell activation, are suppressed in these mice. We further provide evidence that IRF5, activated by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), binds to the promoters of various key genes involved in SSc disease pathology. These observations are congruent with the high level of expression of IRF5, TLR4, and potential endogenous TLR4 ligands in SSc skin lesions. Our study sheds light on the TLR4-IRF5 pathway in the pathology of SSc with clinical implications of targeting the IRF5 pathways in the suppression of disease development.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multisystem connective tissue disease characterized by immune abnormalities, vasculopathy, and extensive tissue fibrosis (1). Based on the results of etiological and genetic studies, the conventional wisdom is that SSc is caused by a complex interplay between genetic factors and environmental influences. For instance, the biggest risk factor for SSc is family history (2). On the other hand, concordance for SSc is around 5% in twins and is similar in monozygotic and dizygotic twins, whereas antinuclear antibodies are detected more frequently in the healthy monozygotic twin sibling than in the healthy dizygotic twin sibling of an SSc patient (3). In addition, most SSc susceptibility genes are HLA haplotypes and non-HLA immune-related genes that are shared by other collagen diseases (4). Therefore, genetic factors are likely associated with autoimmunity, increasing the susceptibility to autoimmune diseases including SSc, but additional environmental factors are required to induce clinically definite SSc in genetically predisposed individuals. Despite these etiological and genetic data, the entire process of the SSc development and pathogenesis remains elusive.

Therefore it is important to elucidate the molecular mechanism(s) underlying SSc pathogenesis. In this regard, much attention has been focused recently on the innate immune signaling via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in various pathological conditions. For instance, fibroblasts and endothelial cells in SSc lesional skin highly express TLR4, originally identified as the receptor for bacterial LPS, and TLR4 signaling amplifies the sensitivity to TGF-β in dermal fibroblasts (5–7). It also was shown that dermal and lung fibrosis is attenuated in bleomycin (BLM)-treated TLR4-deficient mice (7). Endogenous potential TLR4 ligands are up-regulated in SSc lesional skin (5–7), and serum levels correlate with severe organ involvement and immunological abnormalities (8, 9). Therefore, the TLR4 signaling pathway is suspected to play a central role in the SSc pathogenesis.

Although how the TLR4 signaling pathway contributes to SSc pathogenesis remains enigmatic, it is interesting that several independent case-control and genome-wide association studies identify IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), a member of the IFN regulatory factor (IRF) family, as an SSc susceptibility gene (10–15). IRFs were identified primarily in the research of the type I IFN system and have been shown to have functionally diverse roles in the regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses (16). Reflecting such property of IRFs, SNPs of IRFs have been linked to the development of various immune and inflammatory disorders. IRF5 is of particular interest, being implicated in multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and SSc (14). Thus far an association of certain SNPs within the IRF5 promoter with the risk and severity of SSc has been reported (10–15), but whether and how IRF5 is activated to contribute to disease development remains unknown.

Stimulation of TLRs triggers the activation of myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88)-dependent and/or independent pathways (16). IRF5 is activated via the MyD88 pathway in dendritic cells and macrophages (17). TLR-activated IRF5 mediates the induction of genes IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α (17). Hence, an intriguing possibility is that TLR4-mediated activation of IRF5 is involved in SSc. We therefore studied the role of IRF5 in the regulation of genes associated with the susceptibility to and the severity of SSc using IRF5-deficient mice in the context of TLR4 signaling. We show that IRF5, activated by TLR4, binds to the promoters of various key genes involved in the disease symptoms. We discuss our findings in terms of the complexity of SSc and its clinical implications.

Results

Involvement of IRF5 in the Fibrosis- and Fibrillogenesis-Related Genes in Dermal Fibroblasts.

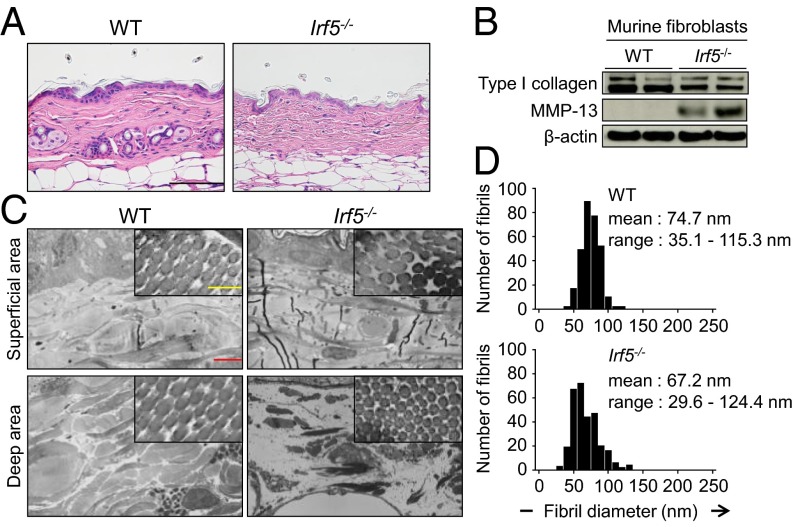

First, to investigate the role of IRF5 in skin homeostasis, we examined by histology the skin of Irf5−/− mice (12 wk after birth) without BLM treatment. As shown in Fig. 1A, thinner collagen bundles were found in the dermis of Irf5−/− mice than in the dermis of WT littermate mice, but other skin structures in Irf5−/− mice looked normal. Consistent with this finding, collagen content decreased in the skin of Irf5−/− mice (Fig. S1A), and Irf5−/− dermal fibroblasts exhibited lower expression of type I collagen and higher expression of matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)-13 (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B). Further analyses with electron microscopy delineated thinner collagen fibrils, especially in deep dermis (Fig. 1C), and higher variability in fibril diameter in Irf5−/− mice (Fig. 1D), suggesting an abnormality in collagen fibrillogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Loss of Irf5 impaired collagen metabolism and fibrillogenesis in vivo. (A) Representative skin image of WT and Irf5−/− mice. (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (B) Immunoblotting with cell lysates from WT and Irf5−/− murine dermal fibroblasts. (C) Ultrastructure of dermal collagen fibrils evaluated by electron microscopy. (Yellow scale bar, 200 nm; red scale bar, 2 µm.) (D) Frequency distribution profiles of fibril diameter in the dermis of WT and Irf5−/− mice (500 collagen fibrils per group).

Fig. S1.

(A) Collagen contents measured by hydroxyproline assay with skin samples (n = 5). (B) mRNA levels of the Col1a1, Col1a2, and Mmp13 genes determined by qRT-PCR in WT and Irf5−/− murine dermal fibroblasts (n = 9). (C) ChIP assay carried out with murine dermal fibroblasts and anti-IFR5 antibody (n = 4). (D) mRNA levels of fibrillogenesis-related genes determined by qRT-PCR in WT and Irf5−/− murine dermal fibroblasts (n = 9). (E) mRNA levels of collagen metabolism- and fibrillogenesis-related genes determined by qRT-PCR in the skin of WT and Irf5−/− mice (n = 5). *P < 0.05 by two-tailed unpaired t test.

Interestingly, the ChIP assay revealed IRF5 binding to the promoters of the collagen, type 1, α1 (Col1a1), collagen, type 1, α2 (Col1a2), and Mmp13 genes, indicating the potential involvement of IRF5 in the regulation of these genes (Fig. S1C). In addition, a notable decrease in the mRNAs for fibrillogenesis-related genes, namely a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain with thrombospondin type 1, motif 2 (Adamts2), lysyl oxidase (Lox), decorin (Dcn), and lumican (Lum), was observed in Irf5−/− dermal fibroblasts as compared with WT dermal fibroblasts (Fig. S1D). A similar mRNA expression pattern also was detected in the skin of Irf5−/− mice (Fig. S1E). Thus, IRF5, perhaps constantly but weakly activated in these mice, may influence extracellular matrix homeostasis by regulating fibrosis- and fibrillogenesis-associated gene expression in dermal fibroblasts (see below). It is worth noting that, except for the Dcn gene, these gene-expression profiles are contrary to those of SSc (18).

TLR4-Activated IRF5 Regulates COL1A2 Gene Expression in Dermal Fibroblasts.

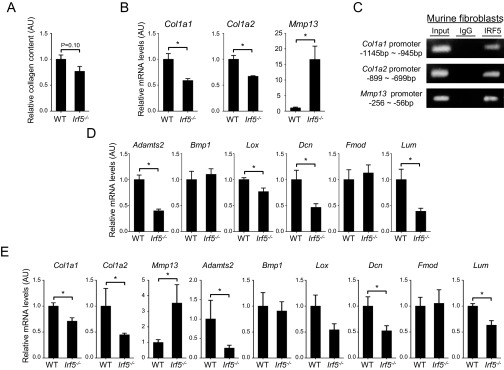

In addition to murine dermal fibroblasts, we also detected IRF5 binding to the promoters for the COL1A1, COL1A2, and MMP1 genes in human dermal fibroblasts (Fig. 2A). In the case of the COL1A2 promoter, sequence-specific binding of IRF5 to the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) was confirmed by an oligonucleotide pull-down assay (Fig. 2B). We further analyzed the role of IRF5 in COL1A2 gene expression in human dermal fibroblasts by a transient assay using a COL1A2-promoter-Luciferase gene and found that ectopic expression of IRF5 increased COL1A2 promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Of note, LPS and TGF-β, known to induce the expression of type I collagen (5), further augmented the reporter gene expression (Fig. 2C), suggesting that TLR4 signaling regulates the transcriptional activity of IRF5. Indeed, IRF5 binding to the COL1A2 promoter was enhanced significantly by simultaneous stimulation of LPS and TGF-β1 (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, the enhancement of IRF5 binding to the COL1A2 promoter also was observed when the cells were stimulated by high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), which is also known to activate TLR4 in lieu of LPS (Fig. 2E) (19). Consistent with this notion, ChIP in Tlr4−/− murine dermal fibroblasts showed a remarkable decrease in IRF5 binding to the Col1a2 promoter (Fig. 2F), but Tlr4 deficiency did not affect the expression of IRF5 (Fig. 2G). Thus, these observations underscore the evidence that the TLR4–IRF5 axis induces COL1A2 gene expression in dermal fibroblasts.

Fig. 2.

TLR4-activated IRF5 induces the profibrotic phenotype in dermal fibroblasts. (A, D, and E) ChIP analysis with anti-IRF5 antibody in human dermal fibroblasts (n = 4). (B) Proteins pulled down by oligonucleotides including WT or mutated ISRE of the COL1A2 promoter were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-IRF5 antibody. (C) Luciferase assay with the COL1A2 promoter construct in human dermal fibroblasts (n = 4). Significant differences shown with asterisks are compared with the columns of the same color at the far left. (F and G) ChIP assay (F) and immunoblotting (G) with anti-IRF5 antibody in Tlr4+/+ and Tlr4−/− murine dermal fibroblasts. In C–E, some cells were stimulated with TGF-β1 and LPS or HMGB1 for 24 h. In D–F, quantification by qRT-PCR is shown in the right panels (n = 5). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by two-tailed unpaired t-test. AU, arbitrary units.

Attenuated Dermal and Pulmonary Fibrosis in BLM-Treated Irf5−/− Mice.

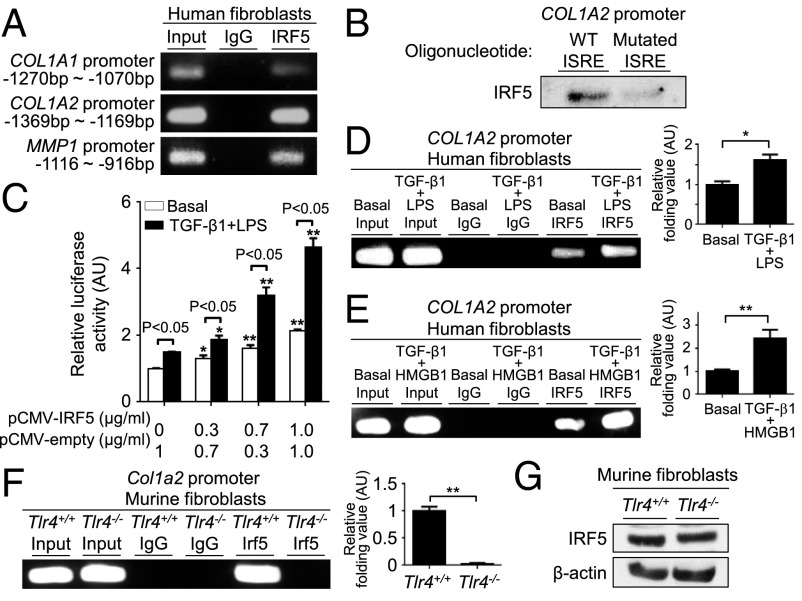

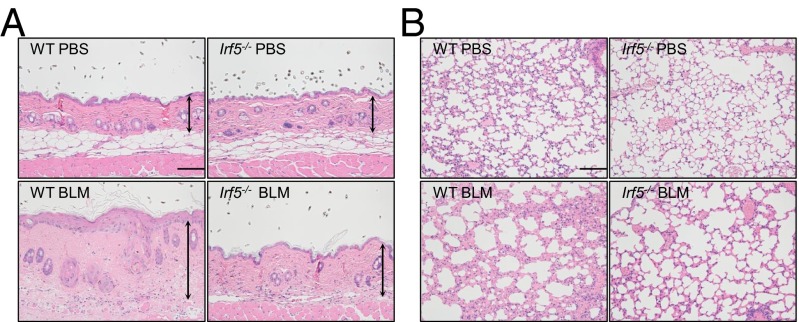

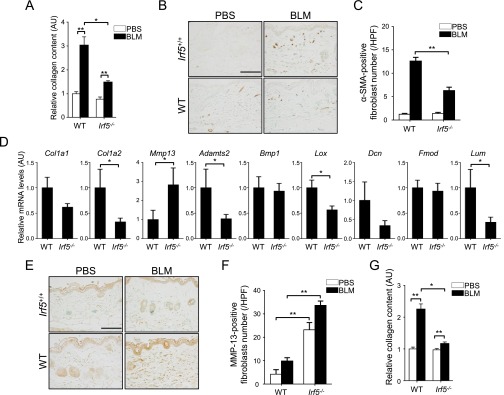

The role of IRF5 in tissue fibrosis was investigated further in BLM-treated mice. In line with in vitro data, dermal thickness, collagen content, and the number of myofibroblasts were significantly decreased in BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice as compared with BLM-treated WT mice (Fig. 3A and Fig. S2 A–C). The expression profile of fibrosis- and fibrillogenesis-related genes in Irf5−/− dermal fibroblasts, which was confirmed at the protein level by immunostaining for MMP-13 (Fig. S2 E and F), was maintained in the skin of BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice (Fig. S2D). Also, lung histology revealed less fibrosis, less destruction of alveolar structures, and less inflammatory cell infiltration in BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice than in BLM-treated WT mice (Fig. 3B and Fig. S2G). Thus, Irf5 deficiency suppresses pathological dermal and pulmonary fibrosis in BLM-treated mice.

Fig. 3.

Deletion of Irf5 attenuates BLM-induced dermal and pulmonary fibrosis. Representative sections of skin (A) and lung (B) in WT and Irf5−/− mice injected with PBS or BLM. Vertical bars with arrows represent dermal thickness. (Horizontal scale bars, 100 µm.)

Fig. S2.

(A and G) Collagen contents of the skin (A) and lung (G) in PBS- or BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice assessed by hydroxyproline assay (n = 5). (B and E) The number of dermal fibroblasts positive for α-SMA (B) and MMP-13 (E) were determined by immunohistochemistry in WT and Irf5−/− mice with PBS or BLM injection (n = 5). (Scale bars, 100 µm.) (C and F) The absolute number of dermal fibroblasts positive for α-SMA (C) and MMP-13 (F) in the dermis of PBS- or BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice. (D) mRNA levels of genes concerned with collagen metabolism and fibrillogenesis were assessed by qRT-PCR in the skin of PBS- or BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice (n = 8). (Scale bars, 100 µm.) *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Promotion of Th1 Immune Polarization and Attenuation of B-Cell Activation by the Absence of IRF5.

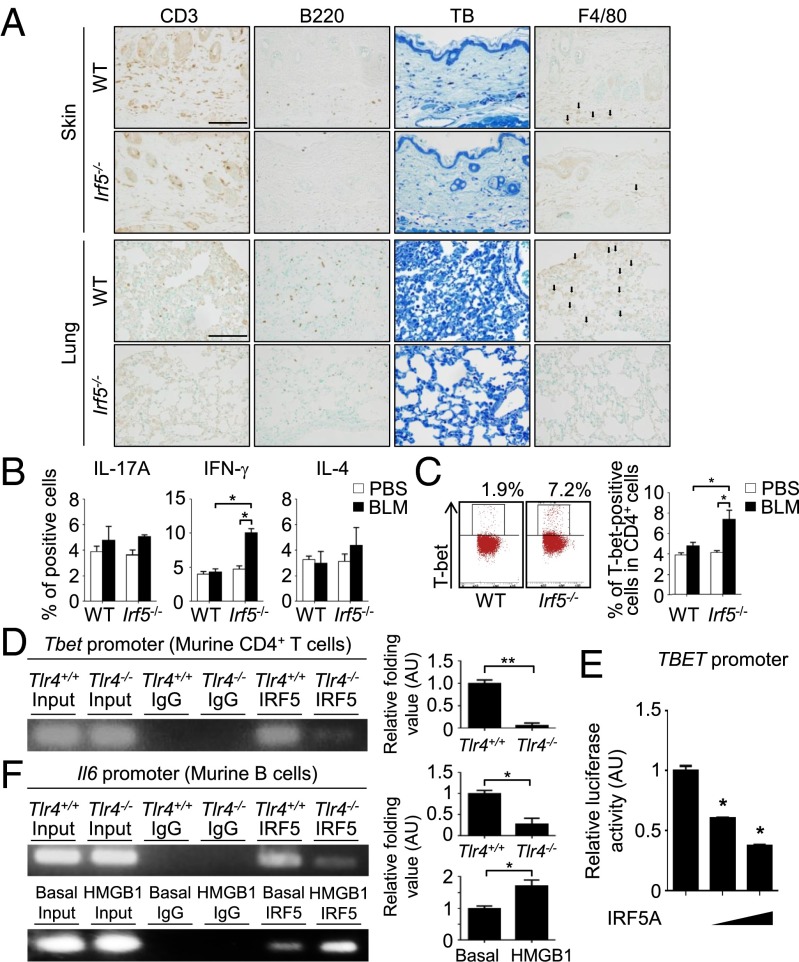

We next asked whether the loss of IRF5 also influences immune cells in BLM-treated mice. As shown in Fig. 4A, immunostaining analysis revealed reduced infiltration of T cells, B cells, mast cells, and macrophages in the skin and lungs of BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice (see also Fig. S3A), suggesting that IRF5 is involved in the BLM-induced inflammatory responses.

Fig. 4.

Loss of Irf5 suppresses the induction of profibrotic inflammatory responses in BLM-treated mice. (A) Immunohistochemistry for CD3, B220, and F4/80 and toluidine blue (TB) staining in the skin and lung of BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) Arrows indicate F4/80+ cells (n = 5). (B and C) Percentage of IL-17A–, IFN-γ–, and IL-4–producing CD4+ T cells (B) and T-bet+ CD4+ T cells (C) in draining lymph nodes of BLM-treated mice determined by intracellular staining (n = 4). Representative FACS plots of intracellular T-bet staining are shown in C. (D and F) ChIP assay with anti-IRF5 antibody in murine CD4+ T cells (D) and B cells (F) with or without homozygous Tlr4 deletion. In some experiments, B cells were stimulated with 10 µg/mL of HMGB1 for 24 h. For each ChIP assay, quantification by qRT-PCR is shown in the panels at right (n = 5). (E) Luciferase assay using the TBET promoter constructs in HEK293T cells cotransfected with IRF5A expression vector (n = 4). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Fig. S3.

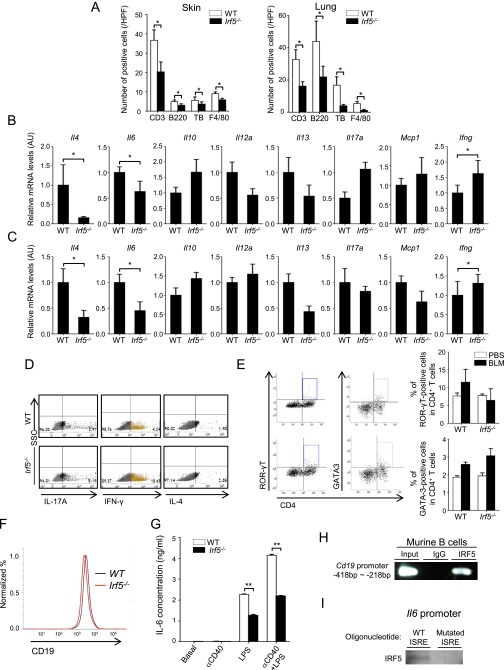

(A) The number of CD3-, B220-, toluidine blue (TB)-, and F4/80-positive cells in the skin and lung of BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice (n = 8). (B and C) mRNA levels of genes encoding fibrosis-related cytokines and chemokines were assessed by qRT-PCR in the skin (B) and lung (C) of BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice (n = 8). (D) Representative FACS plots of intracellular IL-17A, IFN-γ, and IL-4 staining in CD4+ T cells from draining lymph nodes of BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice (n = 4). (E) Representative FACS plots of intracellular ROR-γT and GATA3 staining in CD4+ T cells from draining lymph nodes of BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice (n = 4). (F) CD19 expression in WT and Irf5−/− splenic B cells assessed by flow cytometry. (G) IL-6 concentration in culture supernatants from WT and Irf5−/− splenic B cells stimulated for 48 h with LPS and/or anti-CD40 antibody (αCD40). Eight duplicate cultures of cells pooled from four mice per group were examined. (H) ChIP on splenic B cells assessing the binding of IRF5 to the Cd19 promoter (n = 4). (I) Proteins pulled down by oligonucleotides including WT or mutated ISRE of the Il6 promoter were subjected to immunoblotting for IRF5. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Consistent with this observation, the expression of mRNAs for fibrosis-related cytokines and chemokines was different in the skin and lungs of BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice; IFN-γ mRNA levels were increased significantly, but IL-4 and IL-6 mRNA levels were decreased in the absence of IRF5 (Fig. S3 B and C). These observations suggested a Th1-type immune polarization in BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice. This notion was confirmed by intracellular flow cytometry for cytokines and master transcription factors within lymphocytes of draining lymph nodes, showing an increase in Th1 cells but no change of Th2 and Th17 cells in BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice as compared with BLM-treated WT mice (Fig. 4 B and C and Fig. S3 D and E).

In this regard, we also measured by ChIP assay IRF5 binding to the T-box expressed in T cells (Tbet) promoter in CD4+ T cells. The results suggest that the absence of IRF5 may promote Th1 polarization through induction of the T-bet transcription factor; in other words, IRF5 may serve as a repressor of the Tbet gene (Fig. 4D). IRF5 is known to function as a positive regulator of various genes in immune cells (17), but a transcriptional repressive function has not been reported. To confirm this notion, we carried out a reporter gene-based assay in which activation of a Tbet promoter induces the expression of luciferase (Tbet-Luc) in HEK293T cells. When IRF5A, a constitutive active type isoform of IRF5 which lacks a nuclear export signal (20), was coexpressed with Tbet-Luc, luciferase activity was suppressed in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4E), indicating the repressive action of IRF5 on this promoter. In view of a previously published report that TLR4 signaling in T cells promotes an inflammatory response (21), one may envisage that the TLR4–IRF5 axis also is involved in the BLM-induced immune pathogenesis.

We also extended our study to the role of IRF5 in B cells. We observed that expression of CD19, a critical positive-response regulator (22), was expressed at lower levels in IRF5-deficient B cells (Fig. S3F). Furthermore, IRF5-deficient B cells produced lower amounts of IL-6 than did WT B cells in response to LPS and/or anti-CD40 antibody (Fig. S3G). Of note, the Cd19 and Il6 promoters also were bound by IRF5 (Fig. 4F and Fig. S3H), and the sequence-specific binding of IRF5 to the ISRE of the Il6 promoter also was confirmed (Fig. S3I).

It is interesting that IRF5 binding to the Tbet and Il6 promoters also was suppressed in Tlr4−/− CD4+ T cells and Tlr4−/− B cells, respectively (Fig. 4 D and F). Furthermore, enhanced IRF5 binding to the Il6 promoter by HMGB1 also was observed in B cells (Fig. 4F). Overall, these results indicate that TLR4-activated IRF5 is directly involved in the regulation of Th1 cell differentiation and B-cell activation.

Regulation of Antifibrotic Property by IRF5 in Endothelial Cells.

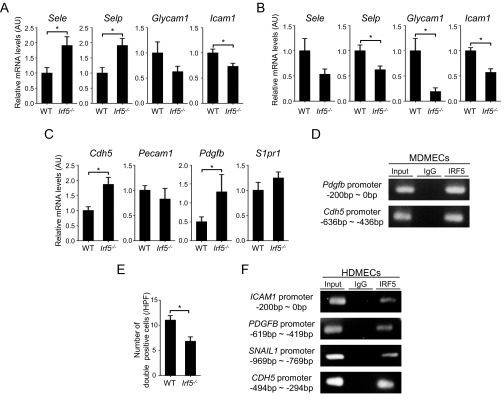

We next examined the vascular aspect of BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice by focusing on cell-adhesion molecules, vascular stability, and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT). In the skin of BLM-treated mice, selectin P (Selp) and selectin E (Sele) mRNA levels were increased by the absence of IRF5, but intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Icam1) mRNA levels were decreased (Fig. S4A). In the lung, the lack of IRF5 significantly reduced Selp and Icam1 and especially glycosylation-dependent cell-adhesion molecule 1 (Glycam1) mRNA expression levels (Fig. S4B). Given that l-selectin, a ligand for GlyCAM-1, and ICAM-1 promote Th2 and Th17 cell infiltration, whereas P-selectin and E-selectin facilitate Th1 cell infiltration, IRF5 may modulate the expression of cell-adhesion molecules, resulting in the promotion of Th1 cell infiltration in BLM-treated mice; this activity is consistent with T-helper cytokine profiles in the skin and lungs of BLM-treated mice (Fig. S3 B and C).

Fig. S4.

(A and B) mRNA levels of the Sele, Selp, Glycam1, and Icam1 genes in the skin (A) and lung (B) of BLM-treated WT and Irf5−/− mice (n = 8). (C) mRNA levels of genes related to angiogenesis and EndoMT in WT and Irf5−/− MDMECs (n = 5). (D) ChIP on MDMECs was carried out using anti-IRF5 antibodies and primers specific for the IRF5-binding site on the Pdgfb and Cdh5 promoters (n = 4). (E) The number of FSP1/VE-cadherin double-positive cells was examined by immunofluorescence (n = 4). (F) ChIP on HDMECs was performed using anti-IRF5 antibodies and primers specific for the IRF5-binding site on the ICAM-1, PDGFB, SNAIL1, and CDH5 promoters (n = 4). *P < 0.05 by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

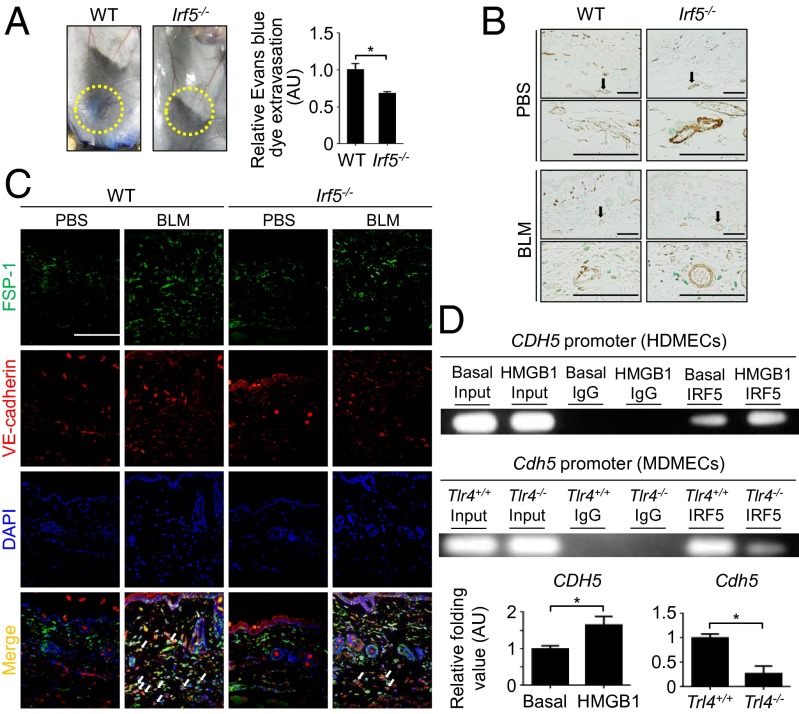

In the vascular permeability assay, the absence of IRF5 attenuated Evans blue dye extravasation induced by BLM (Fig. 5A), suggesting that IRF5 has a suppressive role in vascular stabilization. Because a mural cell phenotype contributes to vascular maturation, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) serves as a marker of mature vessels (23), α-SMA expression in dermal small vessels was evaluated by immunohistochemistry. The loss of IRF5 augments α-SMA expression, irrespective of injected agents (Fig. 5B). In agreement with this observation, dermal microvascular endothelial cells from Irf5−/− mice expressed PDGF-B and vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, which stabilize vasculature by acting on mural cells, at higher levels than cells from WT counterparts (Fig. S4C). Furthermore, IRF5 also bound the Pdgfb and cadherin-5 (Cdh5) promoters as measured by ChIP assay (Fig. S4D). Collectively, Irf5 deficiency is likely to promote vascular stabilization by directly inducing the expression of PDGF-B and VE-cadherin.

Fig. 5.

Irf5 deletion abrogates vascular destabilization and EndoMT induced by BLM. (A, Left) Evaluation for the extravasation of Evans blue dye injected into the caudal vein of BLM-treated mice. (Right) Quantification of Evans blue dye extravasation by formamide extraction (n = 6). (B) Immunohistochemistry for α-SMA in the skin of PBS- or BLM-treated mice. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) (C) Immunofluorescence staining for FSP1 (green), VE-cadherin (red), and DAPI (blue) in skin samples from each group. Arrows represent FSP1/VE-cadherin double-positive cells. (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (n = 4). (D, Upper) ChIP assay with anti-IRF5 antibody in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells with or without HMGB1 stimulation (10 μg/mL for 24 h) and in Tlr4+/+ and Tlr4−/− murine dermal microvascular endothelial cells. (Lower) Quantification by qRT-PCR (n = 5). *P < 0.05 by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Another critical event in the pathology of tissue fibrosis, EndoMT, was assessed further by double immunofluorescence for fibroblast secretory protein-1 (FSP1), a fibroblast marker, and VE-cadherin, an endothelial cell marker, revealing that Irf5 deletion suppressed BLM-dependent induction of double-positive cells (Fig. 5C and Fig. S4E). Importantly, in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMECs), IRF5 was bound to the promoter of the snail family zinc finger 1 (SNAIL1) gene, encoding an important regulator of EndoMT (Fig. S4F). Therefore, in BLM-treated mice Irf5 deficiency appears to inhibit EndoMT directly, contributing to the attenuation of tissue fibrosis.

In HDMECs, IRF5 was bound to the promoters of various genes, including the ICAM1, PDGFB, CDH5, and SNAIL1 genes (Fig. S4F). When HDMECs were treated with HMGB1, the occupancy of the CDH5 promoter by IRF5 was increased (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, Tlr4−/− murine dermal microvascular endothelial cells exhibited a marked reduction of IRF5 binding to the Cdh5 promoter (Fig. 5D). These data indicate that IRF5 regulates the profibrotic/antifibrotic and proangiogenic/angiostatic phenotypes of endothelial cells, depending on TLR4 activation status. Overall, our results in toto suggest a multifaceted transcriptional regulation by IRF5, functioning as either a transcriptional activator or a repressor in this SSc model.

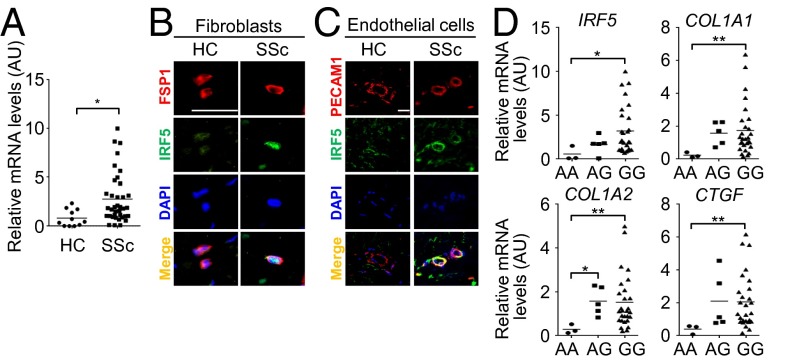

IRF5 Expression and Its Clinical Correlation in SSc Patients.

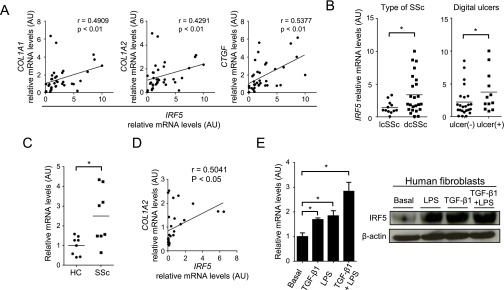

Finally, we evaluated the association of IRF5 expression with clinical features in SSc patients. IRF5 mRNA expression was elevated significantly in SSc lesional skin compared with healthy control skin (Fig. 6A), and this finding was confirmed at the protein level in dermal fibroblasts and endothelial cells by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6 B and C). Notably, increased IRF5 mRNA levels correlated significantly with an increase of the COL1A1, COL1A2, and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) mRNA levels in SSc lesional skin (Fig. S5A). Furthermore, IRF5 mRNA levels were elevated significantly in patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) as compared with patients with limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc) and in SSc patients with a current and past history of digital ulcers as compared with patients without such a history (Fig. S5B). Thus, in so far as we could determine in these SSc patients, these data are consistent with the murine model of SSc.

Fig. 6.

IRF5 expression and its association with the profibrotic condition in SSc. (A) IRF5 mRNA expression in bulk skin from healthy controls (HC) and SSc patients. (B) Immunofluorescence staining for FSP1 (red), IRF5 (green), and DAPI (blue) in skin samples from HC and SSc subjects (n = 4). (Scale bar, 20 µm.) (C) Immunofluorescence staining for platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM1) (red), IRF5 (green), and DAPI (blue) in skin samples from HC and SSc subjects. (Scale bar, 20 µm.) (D) The comparison of relative mRNA levels of the IRF5, COL1A1, COL1A2, and CTGF genes in bulk skin from SSc patients with the AA genotype, AG genotype, and GG genotype. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Fig. S5.

(A) The correlation of IRF5 mRNA levels with COL1A1, COL1A2, and CTGF mRNA levels in the lesional skin of SSc patients. (B) Comparison of IRF5 mRNA levels in the skin from patients with dcSSc or lcSSc and from patients with a current and past history of digital ulcers and from patients without such a history. (C) IRF5 mRNA levels in dermal fibroblasts from healthy controls (HC) and SSc patients. (D) The correlation of IRF5 mRNA levels with COL1A2 mRNA levels in human dermal fibroblasts. (E) IRF5 expression was evaluated in normal dermal fibroblasts stimulated with LPS and/or TGF-β1 at the mRNA and protein levels by qRT-PCR (Left) and immunoblotting (Right), respectively (n = 5). *P < 0.05 by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

In in vitro studies we confirmed that IRF5 mRNA levels were elevated in SSc dermal fibroblasts as compared with normal dermal fibroblasts (Fig. S5C) and correlated positively with COL1A2 mRNA levels in normal and SSc dermal fibroblasts (Fig. S5D). Importantly, in normal human fibroblasts IRF5 expression was increased by LPS and/or TGF-β stimulation at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. S5E). Therefore IRF5 itself may be up-regulated in response to profibrotic stimuli in SSc dermal fibroblasts.

The SNP rs4728142 is located in the IRF5 promoter, and its minor allele A is seen in 9% of Japanese population (24). Supporting the relationship between the rs4728142 A allele and less serious clinical presentation (24), IRF5 mRNA levels in the lesional skin were observed to be significantly lower in SSc patients with the AA genotype than in those with the GG genotypes (Fig. 6D). Importantly, COL1A1, COL1A2, and CTGF mRNA levels were decreased significantly in SSc patients with the AA genotype as compared with those with the GG genotype (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, this allele tended to be related to milder interstitial lung disease with higher percent diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (%DLco) (Table S1). Therefore, the rs4728142 A allele leads to a milder clinical presentation of SSc, possibly correlated with inhibited activation of fibroblasts.

Table S1.

Clinical and laboratory data of SSc patients enrolled for the analysis of SNP rs4728142

| Clinical and laboratory features | GG genotype n = 28 | GA or (AA) genotype n = 8 (3) | P value |

| dcSSc | 20 | 4 (2) | 0.40 |

| Antibodies | |||

| Topo-I | 12 | 3 (1) | 1.0 |

| ACAs | 5 | 2 (1) | 0.64 |

| RNAPIII | 3 | 1 (1) | 1.0 |

| Others | 11 | 4 (1) | 0.69 |

| ILD | 16 | 4 (1) | 1.0 |

| %VC <80% | 7 | 1 (0) | 0.65 |

| %DLco <70% | 10 | 0 (0) | 0.076 |

| Elevated RVSP | 6 | 0 (0) | 0.30 |

The numbers of cases with AA genotype are shown in parenthesis. Elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (RSVP) was defined as 35 mmHg or more on echocardiography. ACA, anti-centromere antibody. dcSSc, diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis; DLco, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; ILD, interstitial lung disease; RNAP III, anti-RNA polymerase III antibody; VC, vital capacity; Topo-I, anti-topoisomerase I antibody.

Discussion

In this study we provide the first evidence, to our knowledge, of a critical role of IRF5 in the mouse model of SSc. Reflecting its critical role as a regulator of the immune system, IRF5 has been identified as a susceptibility gene in various diseases related to immune abnormalities, including SSc (14). Our study reveals that IRF5 is involved in many aspects of pathological processes (e.g., fibrotic and vascular aspects and immune cell abnormalities), as either a transcriptional activator or a repressor. Supporting this idea, IRF5 was observed to bind the promoters of various target genes in fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and lymphocytes. Of note, a direct involvement of IRF5 in immune polarization of CD4+ T cells and B-cell activation was suggested also. Most importantly, loss of Irf5 attenuated tissue fibrosis, vascular activation, and inflammation in BLM-treated mice. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report disclosing the diverse effects of IRF5 on all three cardinal pathological features of SSc.

Innate immune signaling-mediated fibroblast activation was recently reported in SSc and its animal models. In SSc, serum levels and dermal expression levels of endogenous TLR4 ligands, such as HMGB1, hyaluronan, and fibronectin extra domain, are elevated (5, 6, 8, 9). In in vitro experiments, TLR4 signaling induced by these candidate ligands results in fibroblast activation (5, 6). TLR4 signaling also augments TGF-β signaling and, indeed, TLR4 blockade suppresses basal and TGF-β–dependent activation of fibroblasts (5, 6). Importantly, in Tlr4-deficient mice BLM-induced dermal fibrosis is attenuated significantly despite the elevation of endogenous TLR4 ligands (7). Taken together, TLR4 signaling appears to be involved in pathological dermal fibrosis by directly activating dermal fibroblasts. As described in this study, Irf5−/− dermal fibroblasts exhibited an antifibrotic phenotype under normal physiological conditions. In addition, ectopic expression of IRF5 enhanced COL1A2 promoter activity, especially by the stimulatory signals via TGF-β1 and TLR4, both of which also increase IRF5 expression in human dermal fibroblasts. Most importantly, TLR4 activation augmented IRF5’s occupancy on the COL1A2 promoter in human dermal fibroblasts, whereas IRF5 binding to the Col1a2 promoter was reduced remarkably in Tlr4−/− murine dermal fibroblasts. Therefore, the amplification of TGF-β stimulation by TLR4 signaling may be exerted, at least partially, through IRF5 activation in dermal fibroblasts. Given that the skin phenotype of Irf5−/− mice was largely contrary to that of human SSc at the histological and ultrastructural levels and that IRF5 was up-regulated in SSc dermal fibroblasts, we conclude IRF5 plays a pivotal role in tissue fibrosis in SSc. This notion also is supported by the significant positive correlation of IRF5 mRNA levels with COL1A1, COL1A2, and CTGF mRNA levels in SSc lesional skin.

SSc vasculopathy is marked by specific structural and functional abnormalities (1). The structural changes of SSc vasculature are largely attributable to vascular instability closely related to the altered phenotype of mural cells. In SSc lesional skin, α-SMA expression is decreased in mural cells, reflecting the weak interaction of endothelial cells with mural cells and the activation of proangiogenic signaling pathways (23). This feature was reproducible in BLM-treated mice, but in Irf5−/− mice a high α-SMA expression was maintained in the skin vasculature even after BLM injection, indicating that IRF5 is a key regulator of the balance between angiostatic and proangiogenic conditions. Consistent with this notion, IRF5 bound the promoters of the CDH5 and PDGFB genes encoding key molecules—VE-cadherin and PDGF-B, respectively—regulating vascular stabilization and angiogenesis. Because of its involvement in mechanisms connecting vascular activation and tissue fibrosis, EndoMT is a critical pathological event in human and murine models of SSc (25, 26). Because the loss of Irf5 decreased the number of double-positive cells for FSP1 and VE-cadherin in the perivascular region of BLM-treated skin, IRF5 is implicated as a critical regulator of EndoMT, as also was confirmed by IRF5 binding to the SNAIL1 promoter. Importantly, IRF5 occupancy on the CDH5 promoter was enhanced by TLR4 activation. Together with the evidence that TLR4 and its endogenous ligands have been implicated in angiogenesis (27, 28), the present data provide a previously unidentified insight into the role of IRF5 in TLR4-mediated angiogenesis and suggest that the TLR4–IRF5 axis potentially regulates vascular features of SSc.

The regulation of CD4+ T-cell infiltration by cell adhesion molecules has attracted much attention in the context of pathological tissue fibrosis, including SSc and its animal models (25, 29). Studies with mice deficient for cell adhesion molecules have revealed that ICAM-1 and GlyCAM-1 promote tissue fibrosis along with the infiltration of Th2/Th17 cells, macrophages, and mast cells, whereas P-selectin and E-selectin suppress tissue fibrosis accompanying Th1 cell infiltration in response to BLM (29). In lesional skin of early dcSSc, the expression levels of the profibrotic cell adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and GlyCAM-1 are increased relative to that of the antifibrotic cell adhesion molecules E-selectin and P-selectin (25). Therefore our observation that the deletion of Irf5 reduced the relative expression of profibrotic cell adhesion molecules to antifibrotic molecules, in turn leading to the decreased infiltration of macrophages and mast cells and a Th1-predominant cytokine balance, indicates a critical role for IRF5 in the induction of profibrotic inflammation. In addition, we also demonstrated that Th1-skewed immune polarization in BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice is linked to IRF5 binding to the Tbet promoter, suggesting that IRF5 directly suppresses Th1 cell differentiation. Given that IRF5’s occupancy of the Tbet promoter was decreased in Tlr4−/− CD4+ T cells, the activation of TLR4–IRF5 axis promotes a Th2/Th17-predominant inflammatory condition through the direct suppression of Th1 cell differentiation, which may be characteristic of SSc (1).

B-cell activation also is an important part of immune abnormalities in SSc (22). In addition to fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and T cells, deletion of Irf5 induced the phenotypical alteration of B cells, such as down-regulation of CD19 and decreased IL-6 release, a state contrary to SSc B cells. Furthermore, IRF5 bound the Cd19 and Il6 promoters in murine B cells, and occupancy of the Il6 promoter was decreased in Tlr4−/− B cells and increased in Tlr4+/+ B cells upon TLR4 activation. Therefore, the TLR4–IRF5 axis directly regulates B-cell activation. Given that Il6 mRNA levels were decreased markedly in the skin of BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice and that IL-6 is a classic inflammatory cytokine produced by various cells, we surmise that IRF5 regulates IL-6 production in other cell types. Because IL-6 enhances collagen synthesis by inducing myofibroblastic differentiation, promotes Th2 and Th17 differentiation, and inhibits Th1 polarization (30, 31), the loss of IL-6 production largely contributes to the attenuation of tissue fibrosis in BLM-treated Irf5−/− mice.

Based on data in mice, it is assumed that up-regulated expression of IRF5 is involved in the development of three cardinal features of SSc. Supporting this idea, IRF5 expression was increased in dermal fibroblasts and vascular cells in the lesional skin of SSc patients. Furthermore, IRF5 mRNA levels correlated positively with COL1A1, COL1A2, and CTGF mRNA levels in SSc dermal fibroblasts. Moreover, as is consistent with the linking of rs4728142 A allele to a milder clinical phenotype resulting from the loss of IRF5 induction, SSc dermal fibroblasts with the AA genotype expressed COL1A1, COL1A2, and CTGF mRNA at lower levels than SSc dermal fibroblasts with the GG genotype. Reflecting the role of IRF5 in SSc vasculopathy, SSc patients with a current and past history of digital ulcers had higher IRF5 mRNA levels than patients with no history of digital ulcers. Given that SSc progresses via a complex interaction between fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells with SSc-specific phenotypes, the attenuation of SSc phenotypes in each of those cells resulting from IRF5 down-regulation appears to result in milder clinical symptoms of this disease. To our knowledge, these are the first data providing a molecular basis for an association of the rs4728142 A allele with a milder SSc phenotype.

In summary, we provide evidence that IRF5 is involved in the three cardinal pathological processes of SSc through the direct transcriptional regulation of target genes in various cell types. In particular, it is interesting that IRF5 could serve as a potent repressor for the Tbet gene, because IRF5 acts primarily as a potent inducer of various immune-related and inflammatory genes (17). Also, contrary to our previous findings on serum MMP-13 levels and endothelial VE-cadherin expression in SSc (23, 32), Irf5 deficiency induced Mmp13 gene expression in dermal fibroblasts and Cdh5 gene expression in endothelial cells, indicating a role for IRF5 as a transcriptional repressor in various types of cells. In this regard, it may be worth recalling that such a bifunctional action has been shown for IRF3 (20). Obviously, further work is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which IRF5 exerts a repressive function. Importantly, our study revealed the contribution of innate immune signaling via the TLR4–IRF5 axis to the induction of SSc phenotypes in various cell types, offering clues for further understanding of the roles of environmental factors and endogenous ligands in the development and persistence of disease. Finally, our study may provide impetus for new drug development by targeting IRF5 in the treatment of SSc.

Methods

All experimental procedures were approved by the ethical committee of University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and healthy individuals. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All animal studies and procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Experimentation of University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine. Generation of BLM-treated mice, histological assessment, the hydroxyproline assay, transmission electron microscopy, immunoblotting, RNA isolation, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), ChIP, the oligonucleotide pull-down assay, the reporter assay, flow cytometric analysis, the vascular permeability assay, immunofluorescence, cell culture, plasmid information, and the SNP genotyping assay are described in SI Methods. Primer sequences for qRT-PCR and ChIP are summarized in Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

Table S2.

Sequences of the primers used for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

| Col1a1 | 5′-GCCAAGAAGACATCCCTGAAG-3′ | 5′-TGTGGCAGATACAGATCAAGC-3′ |

| Col1a2 | 5′-CACCCCAGCGAAGAACTCATA-3′ | 5′-GCCACCATTGATAGTCTCTCC-3′ |

| Mmp13 | 5′-TGGACCTTCTGGTCTTCTGG-3′ | 5′-TCATGGGCAGCAACAATAAA-3′ |

| Adamts2 | 5′-AGTGGGCCCTGAAGAAGTG-3′ | 5′-CAGAAGGCTCGGTGTACCAT-3′ |

| Bmp1 | 5′-AGCAGGCTGCAGTTCTCAGACAGC-3′ | 5′-GAATGTGTTCCGGGCATAGTGCAT-3′ |

| Lox | 5′-CAGGCTGCACAATTTCACC-3′ | 5′-CAAACACCAGGTACGGCTTT-3′ |

| Dcn | 5′-TGAGCTTCAACAGCATCACC-3′ | 5′-AAGTCATTTTGCCCAACTGC-3′ |

| Fmod | 5′-CAATGTCTACACCGTCCCTGA-3′ | 5′-AGAAGGCTGCTGGAGTTGAAG-3′ |

| Lum | 5′-AGATGCTTGATCTTGGAGTAAGACAGT-3′ | 5′-CAATGAACTTGAAAAGTTTGATGTGAA-3′ |

| Selp | 5′-TCCAGGAAGCTCTGACGTACTTG-3′ | 5′-GCAGCGTTAGTGAAGACTCCGTAT-3′ |

| Sele | 5′-TGAACTGAAGGGATCAAGAAGACT-3′ | 5′-GCCGAGGGACATCATCACAT-3′ |

| Icam1 | 5′-GACGCAGAGGACCTTAACAG-3′ | 5′-GACGCCGCTCAGAAGAAC-3′ |

| Glycam1 | 5′-GACGCAGAGGACCTTAACAG-3′ | 5′-GACGCCGCTCAGAAGAAC-3′ |

| Il4 | 5′-CAACGAAGAACACCACAGAG-3′ | 5′-GGACTTGGACTCATTCATGG-3′ |

| Il6 | 5′-GATGGATGCTACCAAACTGGAT-3′ | 5′-CCAGGTAGCTATGGTACTCCAGA-3′ |

| Il10 | 5′-TTTGAATTCCCTGGGTGAGAA-3′ | 5′-ACAGGGGAGAAATCGATGACA-3′ |

| Il12a | 5′-ACTCTGCGCCAGAAACCTC-3′ | 5′-CACCCTGTTGATGGTCACGAC-3′ |

| Il13 | 5′-TGAGGAGCTGAGCAACATCACACA-3′ | 5′-TGCGGTTACAGAGGCCATGCAATA-3′ |

| Il17a | 5′-CTCCAGAAGGCCCTCAGACTAC-3′ | 5′-AGCTTTCCCTCCGCATTGACACAG-3′ |

| Mcp1 | 5′-CATCCACGTGTTGGCTCA-3′ | 5′−GATCATCTTGCTGGTGAATGAGT-3′ |

| Ifng | 5′-TCAAGTGGCATAGATGTGGAAGAA-3′ | 5′-TGGCTCTGCAGGATTTTCATG-3′ |

| Cdh5 | 5′-GTTCAAGTTTGCCCTGAAGAA-3′ | 5′-GTGATGTTGGCGGTGTTGT-3′ |

| Pecam1 | 5′-CGGTGTTCAGCGAGATCC-3′ | 5′-CGACAGGATGGAAATCACAA-3′ |

| Pdgfb | 5′-CGGCCTGTGACTAGAAGTCC-3′ | 5′-GAGCTTGAGGCGTCTTGG-3′ |

| S1pr1 | 5′-CGGTGTAGACCCAGAGTCCT-3′ | 5′-AGCTTTTCCTTGGCTGGAG-3′ |

| Snail1 | 5′-GCCGGAAGCCCAACTATAGCGA-3′ | 5′-TTCAGAGCGCCCAGGCTGAGGTACT-3′ |

| Gapdh | 5′-CGTGTTCCTACCCCCAATGT-3′ | 5′-TGTCATCATACTTGGCAGGTTTCT-3′ |

| IRF5 | 5′-GCCTTGTTATTGCATGCCAGC-3′ | 5′-AGACCAAGCTTTTCAGCCTGG-3′ |

| COL1A1 | 5′-CCAGAAGAACTGGTACATCAGCA-3′ | 5′-CGCCATACTCGAACTGGGAAT-3′ |

| COL1A2 | 5′-GATGTTGAACTTGTTGCTGAGG-3′ | 5′-TCTTTCCCCATTCATTTGTCTT-3′ |

| CTGF | 5′-TTGCGAAGCTGACCTGGAAGAGAA-3′ | 5′-AGCTCGGTATGTCTTCATGCTGGT-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGA-3′ | 5′-CATACCAGGAAATGAGCTTGACAA-3′ |

Table S3.

Sequences of the primers used for the ChIP assay

| Gene | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

| Col1a1 | 5′-TCCCTCAGCTACCAAACACA-3′ | 5′-TGCAGAATGAACAGGTAGAAGG-3′ |

| Col1a2 | 5′-GCTGTGGAAGGGGTCATAAA-3′ | 5′-CCCTCCTCCATCCTCTCTCT-3′ |

| Mmp13 | 5′-TTCTGAGGCCTTCAAGGAAA-3′ | 5′-ATAGTGGGGAGAAGCAGCAG-3′ |

| Tbet | 5′-AGGCGTGAGAATGCTCAGAT-3′ | 5′-CCCCAATCTGGGAAAGAGTC-3′ |

| Cd19 | 5′-TAAGCCTGGATCACCAGACC-3′ | 5′-TTTCAGATGAGTGGGTGCAG-3′ |

| Il6 | 5′-TTTCAGCCTGGAATCATTCTG-3′ | 5′-TAACCCCTCCAATGCTCAAG-3′ |

| Cdh5 | 5′-AGCCCATCACCCAGTATTTG-3′ | 5′-GCAGCTGAGAAACGTGACAG-3′ |

| Pdgfb | 5′-CTGAAGGGTGGCAACTTCTC-3′ | 5′-GGCTCGGGTCAGTCTGTCTA-3′ |

| COL1A1 | 5′-CAATGACCGGGATTTTCAAG-3′ | 5′-AAAGCCCCTTCTCCAGTTGT-3′ |

| COL1A2 | 5′-CAGAAGCTGCTGATGGAGTT-3′ | 5′-GGGGGCCTAGTTAGAGTGCT-3′ |

| MMP1 | 5′-GCACCAAGGAGCGAAGATAG-3′ | 5′-GAGAAGACCCCTCATCCACA-3′ |

| ICAM1 | 5′-CCGATTGCTTTAGCTTGGAA-3′ | 5′-CCTTTATAGCGCTAGCCACCT-3′ |

| PDGFB | 5′-GACGGGAAGATCATGTTGGT-3′ | 5′-AACCTGGAGATGGGGCTATT-3′ |

| SNAIL1 | 5′-CCGATTGCTTTAGCTTGGAA-3′ | 5′-CCTTTATAGCGCTAGCCACCT-3′ |

| CDH5 | 5′-ACCTGCCTGAGACAGAGGAA-3′ | 5′-CCTGGGAATCTGTCCTTTGA-3′ |

Mice.

C57BL/6 female mice (6 to 8 wk old) were used in this study. Irf5−/− mice were described previously (17). Tlr4−/− mice and tight skin mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory.

Patients.

cDNA and genomic DNA were prepared from forearm skin samples of 36 SSc patients [33 females; median age (25–75 percentile): 57 y; range 41.0–67.0 y] and 11 healthy donors (8 females; median age, 50 y; range 38.0–69.0 y). Fibroblasts were obtained by skin biopsy from eight sex- and site-matched SSc patients and eight healthy donors of closely matched age.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was carried out with one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests for multiple group comparisons and the two-tailed unpaired t-test for two group comparisons. For comparing two group values that did not follow Gaussian distribution, the two-tailed Mann–Whitney u test was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Within-group distributions are expressed as mean ± SEM.

SI Methods

Generation of BLM-Treated Mice.

BLM (Nippon Kayaku) was prepared and injected into mice of each group for 1 wk on alternate days for histological and immunohistochemical analysis and daily for analysis of cytokine expressions with qRT-PCR, ELISA, and flow cytometry, unless otherwise indicated. Equal volumes of PBS were injected into the mice in control groups. All studies and procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Experimentation of University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine.

Histological Assessment.

On the day after the final injection, mice were killed, and skin and lung sections were taken. Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with H&E and toluidine blue. Immunohistochemistry was performed with the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded skin and lung sections, using antibodies anti–MMP-13 antibody (ab39012; Abcam,), anti–α-SMA antibody (A2547l; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-CD3 antibody (553058, BD Pharmingen), anti-B220 antibody (550286; BD Pharmingen), and anti-F4/80 antibody (MCA497G; AbD Serotec).

Hydroxyproline Assay.

In accordance with the instructions for the QuickZyme Total Collagen Assay (QuickZyme Biosciences), 6-mm punch biopsy skin samples and total left lung were hydrolyzed with 6N HCl, and collagen content was quantified.

Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Samples were obtained from the back skin of 2-mo-old mice of each strain and were fixed, postfixed, rinsed, dehydrated, transferred to propylene oxide, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with tannate, uranyl acetate, and lead citrate and were examined with a JEM-1200EX electron microscope (JEOL Ltd.). Multiple micrographs of cross-sections of dermal collagen fibrils were chosen randomly and used for morphometry. Mean diameter, range, and frequency distribution profiles were obtained by manually measuring the smallest diameter of 500 collagen fibrils.

Immunoblotting.

Confluent quiescent fibroblasts were serum-starved for 24 h. Whole-cell lysates and nuclear extracts were prepared. Skin and lung samples from mice were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer (sc-24948; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and the supernatants after centrifugation were used. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Life Technologies) and immunoblotting with an antibody dilution of 1:1,000. Bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescent techniques (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primary antibodies were anti-type I collagen antibody (ab34710; Abcam), anti–MMP-13 antibody (ab39012; Abcam), anti-IRF5 antibody (sc-56714; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) and anti–β-actin antibody (A5441; Sigma-Aldrich). The following secondary antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution: anti-mouse IgG-HRP and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (sc-2371 and sc-2955; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-goat IgG-HRP (55363; MP Biomedicals).

RNA Isolation.

Total RNA was isolated from the lower back skin of mice and from the distal one-third of the forearm of SSc patients and healthy controls using RNeasy spin columns (74104; Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kits (170-8891; Bio-Rad).

qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCR was carried out in triplicate using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (4385617; Life Technologies) on an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Life Technologies). The mRNA levels were normalized to those of the GAPDH gene. The relative change in the levels of genes of interest was determined by the 2–∆∆CT method. Dissociation analysis for each primer pair and reaction was performed to verify specific amplification. The sequences of the primers used are shown in Table S2.

ChIP Assay.

The ChIP assay was performed using the EpiQuik ChIP kit (P-2002; Epigentek). Briefly, cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde. The cross-linked chromatin then was prepared and sonicated to an average size of 300–500 bp. The DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated with anti-IRF5 antibody (sc-56714; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Normal rabbit or mouse IgG was used as a negative control. The input corresponds to DNA extracted from the sample before immunoprecipitation. After reversal of cross-linking, the immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and qRT-PCR. The results of qRT-PCR were normalized to input values. The putative IRF5-binding site was predicted by Tfsitescan. The sequences of the primers used are shown in Table S3.

Oligonucleotide Pull-Down Assay.

Oligonucleotides containing biotin on the 5′ nucleotide of the sense strand were used. The sequences of these oligonucleotides were COL1A2 ISRE oligonucleotides: 5′-AGGGGGTGGGGGGAAGGAAGGGAAAAAGATTCTCAGGGAA-3′ and 5′-TTCCCTGAGAATCTTTTTCCCTTCCTTCCCCCCACCCCCT-3′, which correspond to base pairs −1,294 to −1,252 of the COL1A2 promoter containing ISRE; COL1A2-mutated ISRE oligonucleotides: 5′-AGGGGGTGGGGGGAAGGAAGGTCCAAAGATTCTCAGGGAA-3′ and 5′-TTCCCTGAGAATCTTTGGACCTTCCTTCCCCCCACCCCCT-3′, which have mutated ISRE; Il6 ISRE oligonucleotides: 5′- ACCAGGAACTAGTCTGAAAAAGAAACTAACCAAAGGGAAG-3′ and 5′- CTTCCCTTTGGTTAGTTTCTTTTTCAGACTAGTTCCTGGT-3′, which correspond to base pairs −1,160 to −1,153 of the Il6 promoter containing ISRE; Il6 mutated-ISRE oligonucleotides: 5′- ACCAGGAACTAGTCTGAAAAATCCACTAACCAAAGGGAAG-3′ and 5′- CTTCCCTTTGGTTAGTGGATTTTTCAGACTAGTTCCTGGT-3′.

These oligonucleotides were annealed to their respective complementary oligonucleotides at 95 °C for 1 h. Nuclear extracts prepared from dermal fibroblasts from healthy individuals and splenic B cells from WT mice, respectively, were incubated with streptavidin-coupled agarose beads and 500 pmol of each double-stranded oligonucleotide for 2 h at room temperature with gentle rocking. The protein–DNA–streptavidin–agarose complex was washed four times with PBS containing protease inhibitors. The precipitates were subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

Reporter Gene Assay.

Human foreskin fibroblasts were transfected with plasmids using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent (06365787001l; Roche). The cells were cultured for 24 h, treated with TGF-β1 and LPS or left untreated for the next 24 h, and then harvested. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent for 48 h and then were harvested. The activity of both firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase was measured with an AB-2200 luminometer (ATTO) using the dual luciferase reporter system (E1910; Promega). The activity of firefly luciferase was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase (E2241; Promega).

Flow Cytometric Analysis.

WT and Irf5−/− mice were treated with BLM or PBS for 7 d. On the day after the final injection, mice were killed, and lymphocytes from draining lymph nodes of the lesional skin (i.e., axillary and inguinal lymph nodes) were obtained. In the surface-staining experiments, cells were stained with antibodies against CD19 (6D5), CD3 (17A2), and CD4 (GK1.5) (all from BioLegend). In intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate and 1 µg/mL ionomycin (P8139 and I0634; Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of 1 µg/mL brefeldin A (GolgiStop; 347688; BD Pharmingen) for 4 h. Cells were washed, stained for CD4, treated with fixative/permeabilization buffer (BD Pharmingen), and then stained with anti–IL-4 (11B11), anti–IL-17A (TC11.18H10), and anti–IFN-γ (XMG1.2) antibodies (all from BioLegend). In experiments analyzing transcription factors, antibodies against retinoic acid receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor γt (ROR γt) (B2D; eBioscience), T-bet (4B10; BioLegend), and GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3) (16E10A23; BioLegend) were used. Cells were analyzed on a FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The populations of positive and negative cells were determined using nonreactive isotype-matched antibodies as controls.

Vascular Permeability Assay.

Evans blue dye (E2020-10G; Sigma) (0.5 g) in 200 µL of 0.9% saline was injected into the tail vein, and mice were killed 30 min later. The presence of vascular leakage was evaluated macroscopically in the skin, and 6-mm pieces of full-thickness back skin were removed, dried, and homogenized. The dye was extracted with formamide (1.5 mL) and quantified by spectrophotometer (absorbance 620 nm).

Immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence was carried out with human and murine skin sections in which rabbit anti–FSP-1 antibody (ab27957; Abcam) and goat anti–VE-cadherin antibody (sc-6458; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used as primary antibodies, and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (sc-2090; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (A-21432; Life Technologies) were used as secondary antibodies. Mouse anti-IRF5 antibody (sc-56714; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit anti–FSP-1 antibody were used as primary antibodies, and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (AP192F; Merck Millipore) and Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (A-31572; Life Technologies) were used as secondary antibodies. Mouse anti-IRF5 antibody and goat anti-PECAM1 antibody (sc-1506; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used as primary antibodies; FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody and Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-goat IgG antibody were used as secondary antibodies. Coverslips were mounted using Vectashield with DAPI (H-1200; Vector Laboratories), and staining was examined using a Bio Zero BZ-8000 fluorescence microscope (Keyence) at 495 nm (green), 565 nm (red), and 400 nm (blue).

Cell Culture.

Human dermal fibroblasts and HEK293T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Fibroblasts and HEK293T cells were cultured in minimum essential medium with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotic antimycotic solution. These cells were maintained individually as monolayers at 37 °C in 95% air and 5% CO2. HDMECs were purchased from Takara Bio Inc. and were cultured on collagen-coated tissue-culture plates in EBM-2 medium supplemented with the EGM-2 Bullet Kit (Lonza). Mouse dermal fibroblasts, dermal microvascular endothelial cells, splenic B cells, and CD4+ T cells were isolated and cultured. Primary WT, Irf5−/−, and Tlr4−/− mouse dermal fibroblasts were purified, passaged once, and used for experiments. To obtain dermal microvascular endothelial cells, a cell suspension obtained from dermal collagenase digestion was stained with anti-CD31 microbeads (130-097-418; Miltenyi Biotec) and isolated with magnetic sorting. To obtain splenic B cells and CD4+ T cells, a cell suspension obtained from spleens was stained with biotinylated antibody mixture for negative selection (557792 and 558131; BD Biosciences), including CD4, CD43, and TER-119 for B-cell isolation and CD8a, CD11b, CD45R/B220, CD49b, and TER-119 for CD4+ T-cell isolation. Then these cells were stained with magnetic nanoparticles that have streptavidin covalently conjugated to their surface, and targeted cells were isolated using a BD IMagnet (552311; BD Biosciences). In some experiments, dermal fibroblasts were treated with 2 ng/mL TGF-β1 (R & D Systems) and/or 100 ng/mL LPS (L5293; Sigma-Aldrich) or with 10 µg/mL HMGB1 (9050; Chondrex, Inc.) for 24 h or were left untreated. The 105 B cells per well were stimulated with 5 µg/mL LPS and/or 10 µg/mL anti-CD40 antibody (102810; BioLegend). Supernatants were harvested 48 h later and were measured for IL-6 concentration with a specific ELISA kit (M6000B; R&D Systems). CD4+ T cells were stimulated for 24 h with 10 µg/mL HMGB1 or were left untreated.

Plasmid Information.

A fragment of the COL1A2 promoter (base pairs −1,500 to +200) cloned into the cloning site of the pGL4.10 (luc2) vector (E665A; Promega) was made by GenScript. pCMV-IRF5 was a gift from P. M. Pitha-Rowe, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore. IRF5A, a constitutively active isoform of IRF5, was described previously (20). The expression vector for the constitutive active TGF-β type I receptor (TβRI T204D) was a gift from K. Miyazono, University of Tokyo, Tokyo. A fragment of the TBET promoter (base pairs −1,659 to +51) subcloned into a luciferase reporter vector was a gift from W. Leung, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN. Plasmid vectors were amplified in transformed bacteria Escherichia coli (DH5α; 9057; Takara Bio) and were isolated using the Plasmid Midi Kit (12145; Qiagen).

SNP Genotyping Assay.

To detect the SNP rs4728142, a TaqMan SNP genotyping assay (C_2691222_10; Life Technologies) was carried out using genomic DNA extracted from bulk skin samples by the Genomic DNA Purification kit (K0512; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1520997112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Asano Y, Sato S. Vasculopathy in scleroderma. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37(5):489–500. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnett FC, et al. Familial occurrence frequencies and relative risks for systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) in three United States cohorts. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(6):1359–1362. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1359::AID-ART228>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feghali-Bostwick C, Medsger TA, Jr, Wright TM. Analysis of systemic sclerosis in twins reveals low concordance for disease and high concordance for the presence of antinuclear antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(7):1956–1963. doi: 10.1002/art.11173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broen JC, Radstake TR, Rossato M. The role of genetics and epigenetics in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(11):671–681. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharyya S, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling augments transforming growth factor-β responses: A novel mechanism for maintaining and amplifying fibrosis in scleroderma. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(1):192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya S, et al. FibronectinEDA promotes chronic cutaneous fibrosis through Toll-like receptor signaling. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(232):232ra50. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi T, et al. Amelioration of tissue fibrosis by toll-like receptor 4 knockout in murine models of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):254–265. doi: 10.1002/art.38901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshizaki A, et al. Clinical significance of serum HMGB-1 and sRAGE levels in systemic sclerosis: Association with disease severity. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29(2):180–189. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshizaki A, et al. Clinical significance of serum hyaluronan levels in systemic sclerosis: Association with disease severity. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(9):1825–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieudé P, et al. Association between the IRF5 rs2004640 functional polymorphism and systemic sclerosis: A new perspective for pulmonary fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(1):225–233. doi: 10.1002/art.24183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito I, et al. Association of a functional polymorphism in the IRF5 region with systemic sclerosis in a Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(6):1845–1850. doi: 10.1002/art.24600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dieude P, et al. Phenotype-haplotype correlation of IRF5 in systemic sclerosis: Role of 2 haplotypes in disease severity. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(5):987–992. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radstake TR, et al. Spanish Scleroderma Group Genome-wide association study of systemic sclerosis identifies CD247 as a new susceptibility locus. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):426–429. doi: 10.1038/ng.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang L, Chen B, Ma B, Nie S. Association between IRF5 polymorphisms and autoimmune diseases: A meta-analysis. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(2):4473–4485. doi: 10.4238/2014.June.16.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allanore Y, et al. Genome-wide scan identifies TNIP1, PSORS1C1, and RHOB as novel risk loci for systemic sclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(7):e1002091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda K, Taniguchi T. IRFs: Master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(9):644–658. doi: 10.1038/nri1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takaoka A, et al. Integral role of IRF-5 in the gene induction programme activated by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;434(7030):243–249. doi: 10.1038/nature03308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noda S, et al. Simultaneous downregulation of KLF5 and Fli1 is a key feature underlying systemic sclerosis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5797. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H, Antoine DJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. The many faces of HMGB1: Molecular structure-functional activity in inflammation, apoptosis, and chemotaxis. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93(6):865–873. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1212662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Negishi H, et al. Cross-interference of RLR and TLR signaling pathways modulates antibacterial T cell responses. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(7):659–666. doi: 10.1038/ni.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds JM, Martinez GJ, Chung Y, Dong C. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in T cells promotes autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(32):13064–13069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120585109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato S, Fujimoto M, Hasegawa M, Takehara K, Tedder TF. Altered B lymphocyte function induces systemic autoimmunity in systemic sclerosis. Mol Immunol. 2004;41(12):1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asano Y, et al. Endothelial Fli1 deficiency impairs vascular homeostasis: A role in scleroderma vasculopathy. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(4):1983–1998. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharif R, et al. IRF5 polymorphism predicts prognosis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(7):1197–1202. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taniguchi T, et al. Fibrosis, vascular activation, and immune abnormalities resembling systemic sclerosis in bleomycin-treated Fli-1-haploinsufficient mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(2):517–526. doi: 10.1002/art.38948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez SA. Role of endothelial to mesenchymal transition in the pathogenesis of the vascular alterations in systemic sclerosis. ISRN Rheumatol. 2013;2013:835948. doi: 10.1155/2013/835948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murad S. Toll-like receptor 4 in inflammation and angiogenesis: A double-edged sword. Front Immunol. 2014;5:313. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang S, Xu L, Yang T, Wang F. High-mobility group box-1 and its role in angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95(4):563–574. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0713412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshizaki A, et al. Cell adhesion molecules regulate fibrotic process via Th1/Th2/Th17 cell balance in a bleomycin-induced scleroderma model. J Immunol. 2010;185(4):2502–2515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Reilly S, Cant R, Ciechomska M, van Laar JM. Interleukin-6: A new therapeutic target in systemic sclerosis? Clin Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e4. doi: 10.1038/cti.2013.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rincón M, Anguita J, Nakamura T, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Interleukin (IL)-6 directs the differentiation of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185(3):461–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asano Y, et al. Clinical significance of serum levels of matrix metalloproteinase-13 in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(3):303–307. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]