Significance

Midlife increases in suicides and drug poisonings have been previously noted. However, that these upward trends were persistent and large enough to drive up all-cause midlife mortality has, to our knowledge, been overlooked. If the white mortality rate for ages 45−54 had held at their 1998 value, 96,000 deaths would have been avoided from 1999–2013, 7,000 in 2013 alone. If it had continued to decline at its previous (1979‒1998) rate, half a million deaths would have been avoided in the period 1999‒2013, comparable to lives lost in the US AIDS epidemic through mid-2015. Concurrent declines in self-reported health, mental health, and ability to work, increased reports of pain, and deteriorating measures of liver function all point to increasing midlife distress.

Keywords: midlife mortality, morbidity, US white non-Hispanics

Abstract

This paper documents a marked increase in the all-cause mortality of middle-aged white non-Hispanic men and women in the United States between 1999 and 2013. This change reversed decades of progress in mortality and was unique to the United States; no other rich country saw a similar turnaround. The midlife mortality reversal was confined to white non-Hispanics; black non-Hispanics and Hispanics at midlife, and those aged 65 and above in every racial and ethnic group, continued to see mortality rates fall. This increase for whites was largely accounted for by increasing death rates from drug and alcohol poisonings, suicide, and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis. Although all education groups saw increases in mortality from suicide and poisonings, and an overall increase in external cause mortality, those with less education saw the most marked increases. Rising midlife mortality rates of white non-Hispanics were paralleled by increases in midlife morbidity. Self-reported declines in health, mental health, and ability to conduct activities of daily living, and increases in chronic pain and inability to work, as well as clinically measured deteriorations in liver function, all point to growing distress in this population. We comment on potential economic causes and consequences of this deterioration.

There has been a remarkable long-term decline in mortality rates in the United States, a decline in which middle-aged and older adults have fully participated (1‒3). Between 1970 and 2013, a combination of behavioral change, prevention, and treatment (4, 5) brought down mortality rates for those aged 45–54 by 44%. Parallel improvements were seen in other rich countries (2). Improvements in health also brought declines in morbidity, even among the increasingly long-lived elderly (6‒9).

These reductions in mortality and morbidity have made lives longer and better, and there is a general and well-based presumption that these improvements will continue. This paper raises questions about that presumption for white Americans in midlife, even as mortality and morbidity continue to fall among the elderly.

This paper documents a marked deterioration in the morbidity and mortality of middle-aged white non-Hispanics in the United States after 1998. General deterioration in midlife morbidity among whites has received limited comment (10, 11), but the increase in all-cause midlife mortality that we describe has not been previously highlighted. For example, it does not appear in the regular mortality and health reports issued by the CDC (12), perhaps because its documentation requires disaggregation by age and race. Beyond that, the extent to which the episode is unusual requires historical context, as well as comparison with other rich countries over the same period.

Increasing mortality in middle-aged whites was matched by increasing morbidity. When seen side by side with the mortality increase, declines in self-reported health and mental health, increased reports of pain, and greater difficulties with daily living show increasing distress among whites in midlife after the late 1990s. We comment on potential economic causes and consequences of this deterioration.

Midlife Mortality

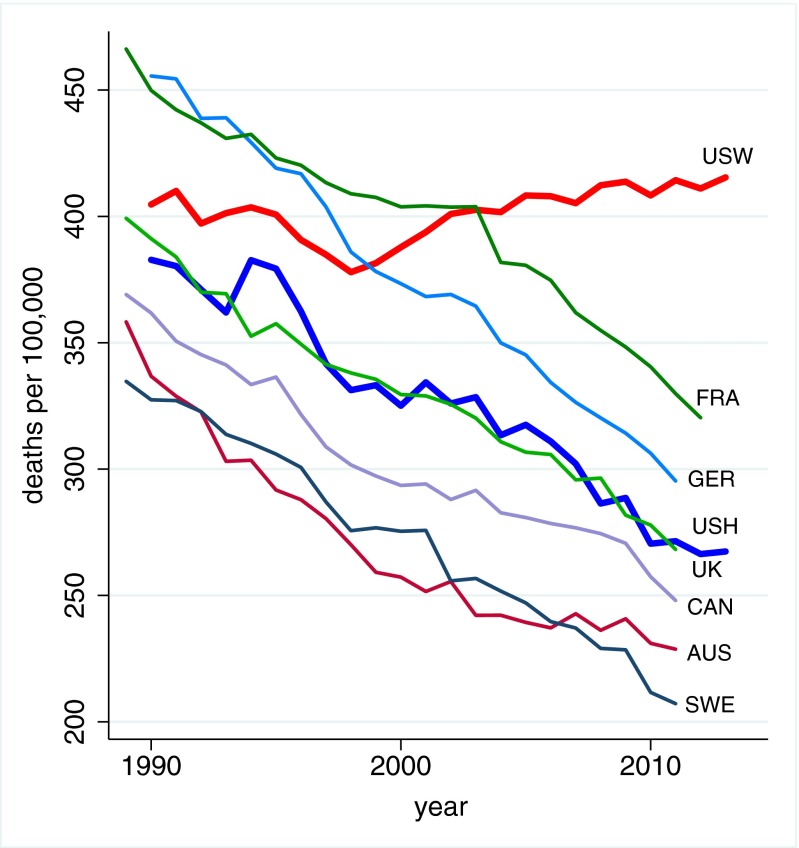

Fig. 1 shows age 45–54 mortality rates for US white non-Hispanics (USW, in red), US Hispanics (USH, in blue), and six rich industrialized comparison countries: France (FRA), Germany (GER), the United Kingdom (UK), Canada (CAN), Australia (AUS), and Sweden (SWE). The comparison is similar for other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

Fig. 1.

All-cause mortality, ages 45–54 for US White non-Hispanics (USW), US Hispanics (USH), and six comparison countries: France (FRA), Germany (GER), the United Kingdom (UK), Canada (CAN), Australia (AUS), and Sweden (SWE).

Fig. 1 shows a cessation and reversal of the decline in midlife mortality for US white non-Hispanics after 1998. From 1978 to 1998, the mortality rate for US whites aged 45–54 fell by 2% per year on average, which matched the average rate of decline in the six countries shown, and the average over all other industrialized countries. After 1998, other rich countries’ mortality rates continued to decline by 2% a year. In contrast, US white non-Hispanic mortality rose by half a percent a year. No other rich country saw a similar turnaround. The mortality reversal was confined to white non-Hispanics; Hispanic Americans had mortality declines indistinguishable from the British (1.8% per year), and black non-Hispanic mortality for ages 45–54 declined by 2.6% per year over the period.

For deaths before 1989, information on Hispanic origin is not available, but we can calculate lives lost among all whites. For those aged 45–54, if the white mortality rate had held at its 1998 value, 96,000 deaths would have been avoided from 1999 to 2013, 7,000 in 2013 alone. If it had continued to fall at its previous (1979‒1998) rate of decline of 1.8% per year, 488,500 deaths would have been avoided in the period 1999‒2013, 54,000 in 2013. (Supporting Information provides details on calculations.)

This turnaround, as of 2014, is specific to midlife. All-cause mortality rates for white non-Hispanics aged 65–74 continued to fall at 2% per year from 1999 to 2013; there were similar declines in all other racial and ethnic groups aged 65–74. However, the mortality decline for white non-Hispanics aged 55–59 also slowed, declining only 0.5% per year over this period.

There was a pause in midlife mortality decline in the 1960s, largely explicable by historical patterns of smoking (13). Otherwise, the post-1999 episode in midlife mortality in the United States is both historically and geographically unique, at least since 1950. The turnaround is not a simple cohort effect; Americans born between 1945 and 1965 did not have particularly high mortality rates before midlife.

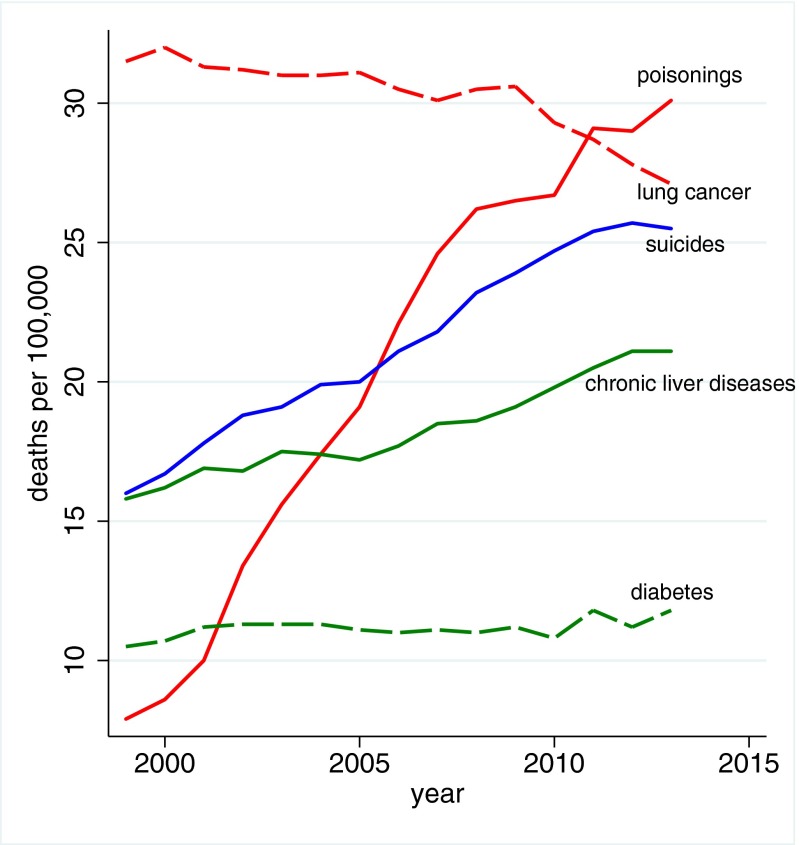

Fig. 2 presents the three causes of death that account for the mortality reversal among white non-Hispanics, namely suicide, drug and alcohol poisoning (accidental and intent undetermined), and chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis. All three increased year-on-year after 1998. Midlife increases in suicides and drug poisonings have been previously noted (14–16). However, that these upward trends were persistent and large enough to drive up all-cause midlife mortality has, to our knowledge, been overlooked. For context, Fig. 2 also presents mortality from lung cancer and diabetes. The obesity epidemic has (rightly) made diabetes a major concern for midlife Americans; yet, in recent history, death from diabetes has not been an increasing threat. Poisonings overtook lung cancer as a cause of death in 2011 in this age group; suicide appears poised to do so.

Fig. 2.

Mortality by cause, white non-Hispanics ages 45–54.

Table 1 shows changes in mortality rates from 1999 to 2013 for white non-Hispanic men and women ages 45–54 and, for comparison, changes for black non-Hispanics and for Hispanics. The table also presents changes in mortality rates for white non-Hispanics by three broad education groups: those with a high school degree or less (37% of this subpopulation over this period), those with some college, but no bachelor’s (BA) degree (31%), and those with a BA or more (32%). The fraction of 45- to 54-y-olds in the three education groups was stable over this period. Each cell shows the change in the mortality rate from 1999 to 2013, as well as its level (deaths per 100,000) in 2013.

Table 1.

Changes in mortality rates 2013–1999, ages 45–54 (2013 mortality rates)

| All-cause mortality | All external causes | Poisonings | Intentional self-harm | Transport accidents | Chronic liver cirrhosis | |

| White non-Hispanics (WNH) | 33.9 (415.4) | 32.8 (84.4) | 22.2 (30.1) | 9.5 (25.5) | −0.9 (13.9) | 5.3 (21.1) |

| Black non-Hispanics | −214.8 (581.9) | −6.0 (68.0) | 3.7 (21.8) | 0.9 (6.6) | −4.3 (14.6) | −9.5 (13.5) |

| Hispanics | −63.6 (269.6) | −2.9 (43.6) | 4.3 (14.4) | 0.2 (7.3) | −4.9 (10.0) | −3.5 (23.1) |

| WNH by education class | ||||||

| 1. Less than high school or HS degree only | 134.4 (735.8) | 68.7 (147.7) | 44.3 (58.0) | 17.0 (38.8) | 1.77 (24.2) | 12.2 (38.9) |

| 2. Some college, no BA | −3.33 (287.8) | 18.9 (59.9) | 14.6 (20.6) | 6.03 (19.6) | −1.90 (9.96) | 3.03 (14.9) |

| 3. BA degree or more | −57.0 (178.1) | 3.57 (36.8) | 4.64 (8.08) | 3.32 (16.2) | −3.63 (5.98) | −0.77 (6.98) |

| Ratios of rates groups 1–3 | ||||||

| 1999 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.4 |

| 2013 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 5.6 |

Over the 15-y period, midlife all-cause mortality fell by more than 200 per 100,000 for black non-Hispanics, and by more than 60 per 100,000 for Hispanics. By contrast, white non-Hispanic mortality rose by 34 per 100,000. The ratio of black non-Hispanic to white non-Hispanic mortality rates for ages 45–54 fell from 2.09 in 1999 to 1.40 in 2013. CDC reports have highlighted the narrowing of the black−white gap in life expectancy (12). However, for ages 45–54, the narrowing of the mortality rate ratio in this period was largely driven by increased white mortality; if white non-Hispanic mortality had continued to decline at 1.8% per year, the ratio in 2013 would have been 1.97. The role played by changing white mortality rates in the narrowing of the black−white life expectancy gap (2003−2008) has been previously noted (17). It is far from clear that progress in black longevity should be benchmarked against US whites.

The change in all-cause mortality for white non-Hispanics 45–54 is largely accounted for by an increasing death rate from external causes, mostly increases in drug and alcohol poisonings and in suicide. (Patterns are similar for men and women when analyzed separately.) In contrast to earlier years, drug overdoses were not concentrated among minorities. In 1999, poisoning mortality for ages 45–54 was 10.2 per 100,000 higher for black non-Hispanics than white non-Hispanics; by 2013, poisoning mortality was 8.4 per 100,000 higher for whites. Death from cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases fell for blacks and rose for whites. After 2006, death rates from alcohol- and drug-induced causes for white non-Hispanics exceeded those for black non-Hispanics; in 2013, rates for white non-Hispanic exceeded those for black non-Hispanics by 19 per 100,000.

The three numbered rows of Table 1 show that the turnaround in mortality for white non-Hispanics was driven primarily by increasing death rates for those with a high school degree or less. All-cause mortality for this group increased by 134 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2013. Those with college education less than a BA saw little change in all-cause mortality over this period; those with a BA or more education saw death rates fall by 57 per 100,000. Although all three educational groups saw increases in mortality from suicide and poisonings, and an overall increase in external cause mortality, increases were largest for those with the least education. The mortality rate from poisonings rose more than fourfold for this group, from 13.7 to 58.0, and mortality from chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis rose by 50%. The final two rows of the table show increasing educational gradients from 1999 and 2013; the ratio of midlife all-cause mortality of the lowest to the highest educational group rose from 2.6 in 1999 to 4.1 in 2013.

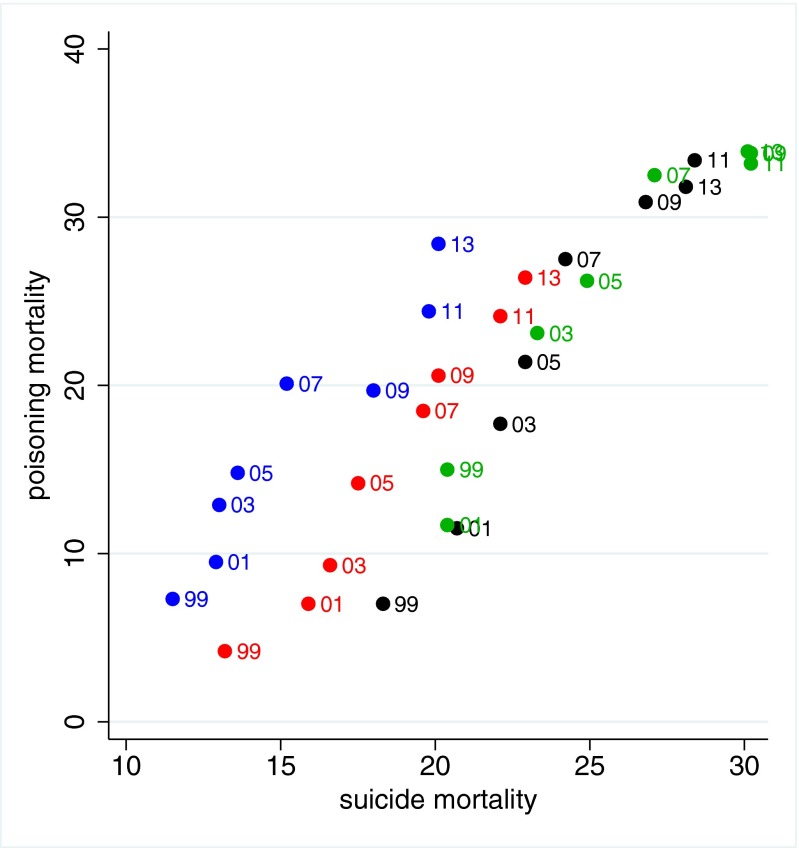

Fig. 3 shows the temporal and spatial joint evolution of suicide and poisoning mortality for white non-Hispanics aged 45–54, for every-other year from 1999 to 2013, for each of the four census regions of the United States. Death rates from these causes increased in parallel in all four regions between 1999 and 2013. Suicide rates were higher in the South (marked in black) and the West (green) than in the Midwest (red) or Northeast (blue) at the beginning of this period, but in each region, an increase in suicide mortality of 1 per 100,000 was matched by a 2 per 100,000 increase in poisoning mortality.

Fig. 3.

Census region-level suicide and poisoning mortality rates 1999–2013. Census regions are Northeast (blue), Midwest (red), South (black), and West (green).

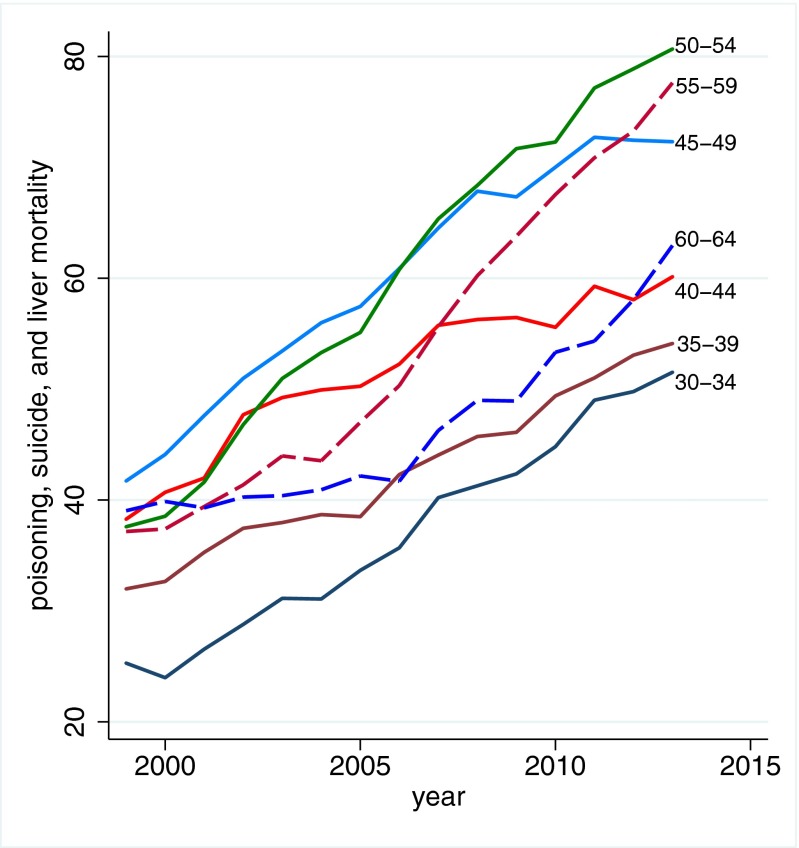

The focus of this paper is on changes in mortality and morbidity for those aged 45–54. However, as Fig. 4 makes clear, all 5-y age groups between 30–34 and 60–64 have witnessed marked and similar increases in mortality from the sum of drug and alcohol poisoning, suicide, and chronic liver disease and cirrhosis over the period 1999–2013; the midlife group is different only in that the sum of these deaths is large enough that the common growth rate changes the direction of all-cause mortality.

Fig. 4.

Mortality by poisoning, suicide, chronic liver disease, and cirrhosis, white non-Hispanics by 5-y age group.

Midlife Morbidity

Increases in midlife mortality are paralleled by increases in self-reported midlife morbidity. Table 2 presents measures of self-assessed health status, pain, psychological distress, difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs), and alcohol use. Each row presents the average fraction of white non-Hispanics ages 45–54 who reported a given health condition in surveys over 2011–2013, followed by the change in the fraction reporting that condition between survey years 1997−1999 and 2011−2013, together with the 95% confidence interval (CI) on the size of that change.

Table 2.

Changes in morbidity, white non-Hispanics 45–54

| Mean 2011–2013 | Δ 1997–1999 | 95% CI of change | |

| Physical health | |||

| Excellent/Very Good* | 0.559 | ‒0.067 | [‒0.070, ‒0.063] |

| Fair/Poor* | 0.159 | 0.043 | [0.040, 0.046] |

| Days physical health was not good* | 4.21 | 1.18 | [1.11, 1.24] |

| Neck pain† | 0.211 | 0.023 | [0.012, 0.033] |

| Facial pain† | 0.068 | 0.013 | [0.007, 0.019] |

| Chronic joint pain‡ | 0.347 | 0.026 | [0.012, 0.040] |

| Sciatica† | 0.140 | 0.026 | [0.018, 0.035] |

| Mental health | |||

| Kessler 6-score ≥ 13† | 0.048 | 0.009 | [0.004, 0.015] |

| Days mental health was not good* | 4.16 | 1.06 | [1.00, 1.12] |

| ADLs, difficulty | |||

| Walking† | 0.124 | 0.029 | [0.020, 0.037] |

| Climbing stairs† | 0.085 | 0.016 | [0.009, 0.023] |

| Standing† | 0.150 | 0.025 | [0.016, 0.034] |

| Sitting† | 0.099 | 0.016 | [0.009, 0.024] |

| Shopping† | 0.088 | 0.022 | [0.015, 0.029] |

| Socializing† | 0.087 | 0.024 | [0.017, 0.031] |

| Activities limited by physical or mental health§ | 0.244 | 0.032 | [0.028, 0.035] |

| Unable to work* | 0.092 | 0.045 | [0.043, 0.047] |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| At risk for heavy drinking§ | 0.074 | 0.017 | [0.015, 0.018] |

| AST > normal range¶ | 0.058 | 0.035 | [0.014, 0.055] |

| ALT > normal range¶ | 0.072 | 0.022 | [‒0.003, 0.047] |

| AST > normal range (BMI < 30)¶ | 0.052 | 0.035 | [0.011, 0.058] |

| ALT > normal range (BMI < 30)¶ | 0.052 | 0.026 | [0.001, 0.052] |

BRFSS 1997–1999 and 2011–2013.

NHIS 1997–1999 and 2011–2013.

NHIS 2002–2003 and 2011–2013.

BRFSS 2001–2003 and 2011–2013.

NHANES 1999–2002 and 2009–2012.

The first two rows of Table 2 present the fraction of respondents who reported excellent or very good health and fair or poor health. There was a large and statistically significant decline in the fraction reporting excellent or very good health (6.7%), and a corresponding increase in the fraction reporting fair or poor health (4.3%). This deterioration in self-assessed health is observed in each US state analyzed separately (results omitted for reasons of space). On average, respondents in the later period reported an additional full day in the past 30 when physical health was “not good.”

The increase in reports of poor health among those in midlife was matched by increased reports of pain. Rows 4–7 of Table 2 present the fraction reporting neck pain, facial pain, chronic joint pain, and sciatica. One in three white non-Hispanics aged 45–54 reported chronic joint pain in the 2011–2013 period; one in five reported neck pain; and one in seven reported sciatica. Reports of all four types of pain increased significantly between 1997−1999 and 2011−2013: An additional 2.6% of respondents reported sciatica or chronic joint pain, an additional 2.3% reported neck pain, and an additional 1.3% reported facial pain.

The fraction of respondents in serious psychological distress also increased significantly. Results from the Kessler six (K6) questionnaire show that the fraction of people who were scored in the range of serious mental illness rose from 3.9% to 4.8% over this period. Compared with 1997–99, respondents in 2011–2013 reported an additional day in the past month when their mental health was not good.

Table 2 also reports the fraction of people who respond that they have more than “a little difficulty” with ADLs. Over this period, there was significant midlife deterioration, on the order of 2–3 percentage points, in walking a quarter mile, climbing 10 steps, standing or sitting for 2 h, shopping, and socializing with friends. The fraction of respondents reporting difficulty in socializing, a risk factor for suicide (18, 19), increased by 2.4 percentage points. Respondents reporting that their activities are limited by physical or mental health increased by 3.2 percentage points. The fraction reporting being unable to work doubled for white non-Hispanics aged 45–54 in this 15-y period.

Increasing obesity played only a part in this deterioration of midlife self-assessed health, mental health, reported pain, and difficulties with ADLs. Respondents with body mass indices above 30 reported greater morbidity along all of these dimensions. However, deterioration in midlife morbidity occurred for both obese and nonobese respondents, and increased prevalence of obesity accounts for only a small fraction of the overall deterioration.

Risk for heavy drinking—more than one (two) drinks daily for women (men)—also increased significantly. Blood tests show increases in the fraction of participants with elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) enzymes, indicators for potential inflammation of, or damage to, the liver. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can also elevate AST and ALT enzymes; for this reason, we show the fractions with elevated enzymes among all respondents, and separately for nonobese respondents (those with body mass index < 30).

As was true in comparisons of mortality rate changes, where midlife groups fared worse than the elderly, most of these morbidity indicators either held constant or improved among older populations over this period. With the exception of neck pain and facial pain, and enzyme test results (for which census region markers are not available), the temporal evolution of each morbidity marker presented in Table 2 is significantly associated with the temporal evolution of suicide and poisonings within census region. (Supporting Information provides details.)

Discussion

The increase in midlife morbidity and mortality among US white non-Hispanics is only partly understood. The increased availability of opioid prescriptions for pain that began in the late 1990s has been widely noted, as has the associated mortality (14, 20‒22). The CDC estimates that for each prescription painkiller death in 2008, there were 10 treatment admissions for abuse, 32 emergency department visits for misuse or abuse, 130 people who were abusers or dependent, and 825 nonmedical users (23). Tighter controls on opioid prescription brought some substitution into heroin and, in this period, the US saw falling prices and rising quality of heroin, as well as availability in areas where heroin had been previously largely unknown (14, 24, 25).

The epidemic of pain which the opioids were designed to treat is real enough, although the data here cannot establish whether the increase in opioid use or the increase in pain came first. Both increased rapidly after the mid-1990s. Pain prevalence might have been even higher without the drugs, although long-term opioid use may exacerbate pain for some (26), and consensus on the effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid use has been hampered by lack of research evidence (27). Pain is also a risk factor for suicide (28). Increased alcohol abuse and suicides are likely symptoms of the same underlying epidemic (18, 19, 29), and have increased alongside it, both temporally and spatially.

Although the epidemic of pain, suicide, and drug overdoses preceded the financial crisis, ties to economic insecurity are possible. After the productivity slowdown in the early 1970s, and with widening income inequality, many of the baby-boom generation are the first to find, in midlife, that they will not be better off than were their parents. Growth in real median earnings has been slow for this group, especially those with only a high school education. However, the productivity slowdown is common to many rich countries, some of which have seen even slower growth in median earnings than the United States, yet none have had the same mortality experience (lanekenworthy.net/shared-prosperity and ref. 30). The United States has moved primarily to defined-contribution pension plans with associated stock market risk, whereas, in Europe, defined-benefit pensions are still the norm. Future financial insecurity may weigh more heavily on US workers, if they perceive stock market risk harder to manage than earnings risk, or if they have contributed inadequately to defined-contribution plans (31).

Our findings may also help us understand recent large increases in Americans on disability. The growth in Social Security Disability Insurance in this age group (32) is not quite the near-doubling shown in Table 2 for the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) measure of work limitation, but the scale is similar in levels and trends. This has been interpreted as a response to the generosity of payments (33), but careful work based on Social Security records shows that most of the increase can be attributed to compositional effects, with the remainder falling in the category of (hard to ascertain) increases in musculoskeletal and mental health disabilities (34); our morbidity results suggest that disability from these causes has indeed increased. Increased morbidity may also explain some of the recent otherwise puzzling decrease in labor force participation in the United States, particularly among women (35).

The mortality reversal observed in this period bears a resemblance to the mortality decline slowdown in the United States during the height of the AIDS epidemic, which took the lives of 650,000 Americans (1981 to mid-2015). A combination of behavioral change and drug therapy brought the US AIDS epidemic under control; age-adjusted deaths per 100,000 fell from 10.2 in 1990 to 2.1 in 2013 (12). However, public awareness of the enormity of the AIDS crisis was far greater than for the epidemic described here.

A serious concern is that those currently in midlife will age into Medicare in worse health than the currently elderly. This is not automatic; if the epidemic is brought under control, its survivors may have a healthy old age. However, addictions are hard to treat and pain is hard to control, so those currently in midlife may be a “lost generation” (36) whose future is less bright than those who preceded them.

Materials and Methods

Mortality Data.

We assembled data on all-cause and cause-specific mortality from the CDC Wonder Compressed and Detailed Mortality files as well as from individual death records from 1989 to 2013. For population by ethnicity and educational status, we extracted data from American Community Surveys and, before 2000, from Current Population Surveys. International data on mortality were taken from the Human Mortality Database www.mortality.org; these are not separated by race and ethnicity. Specific causes of death are constructed for 1999–2013 using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD10) codes: alcoholic liver diseases and cirrhosis (ICD10 K70, K73-74), suicide (X60-84, Y87.0), and poisonings (X40-45, Y10-15, Y45, 47, 49). Poisonings are accidental and intent-undetermined deaths from alcohol poisoning and overdoses of prescription and illegal drugs.

Morbidity Data.

Data are drawn from multiple years of publicly available US national surveys: the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS, 1997–2013) www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm, BRFSS (1997–2013) www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html, and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES, 1999–2011) www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. Details on morbidity variable coding are provided in Supporting Information.

Methods.

Mortality rates are presented as deaths per 100,000. These are not age-adjusted within the 10-y 45–54 age group. Information on education was missing for ∼5% of death records from 1999 to 2013 for white non-Hispanics aged 45–54. For all-cause mortality, deaths with missing education information were assigned an education category based on the distribution of education for deaths with education information, by sex and year (37). For cause-specific mortality, education was assigned based on sex, year, and cause of death.

All morbidity averages are calculated using survey-provided population sampling weights, and are presented without further statistical adjustments. We use 3 y of data to calculate averages (1997−1999 and 2011–2013), to ensure the means reported are not an aberration in any one year. Exceptions are noted.

SI Data

The NHIS and BRFSS both ask whether “health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor,” and we report both positive (excellent/very good) and negative (fair/poor) responses. Table 2 reports responses to this question from the BRFSS; means from the NHIS are not statistically different from those reported. The NHIS asks questions on pain, which vary by type of pain. We score answers that a respondent had an ache or pain in a joint in the past 30 d, with symptoms first appearing more than 3 mo ago, as chronic joint pain, and answers to whether the respondent had pain in the past 3 mo lasting a whole day or more in the neck, face, or lower back pain that spread down either leg below the knee as neck pain, facial pain, and sciatica. The NHIS administers the Kessler six (K6) questionnaire, www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/k6_scales.php, scored to discriminate cases of serious psychological distress (38). We use a threshold of K6 greater than or equal to 13 as an indicator of serious psychological distress/serious mental illness. The BRFSS asks for the number of days in the past 30 mental (physical) health was “not good.” The NHIS asks about respondents’ ability to go about daily living: walking, climbing, standing, sitting, shopping, and participating in social activities. Answers on a five-point scale range from “not at all difficult” to “can’t do at all,” to which we add “do not do.” We report the fraction of people who respond that they have more than “a little difficulty” with each of these activities. The BRFSS asks respondents about current employment. Answers are coded as used for wages, out of work (less than/more than 1 y), homemaker, retired, student, or “unable to work.” We report the fraction responding that they are unable to work. The BRFSS calculates scores of heavy drinking, defined as more than one (two) drinks daily for women (men). NHANES provides results of enzyme tests, and we report the fraction with elevated enzyme readings: AST above a reference level of 48 U/L (units per liter) for men and 43 U/L for women, and ALT above a reference level of 55 U/L for men and 45 U/L for women. We use Mayo Clinic reference levels (39).

SI Materials and Methods

Calculations of deaths that would have been averted (1999−2013) use actual mortality rates observed each year compared with the rates that would have held in each year if the mortality rate had continued to fall at the speed observed for the period 1979–1998 (1.8% per year). We allow those who would have survived to face subsequent mortality risk, and we account for people aging out of the 45–54 age group. Define as the mortality rate observed for whites aged 45–54 in year t. Define as the mortality rate that would have occurred if the mortality rate had continued to fall at 1.8% per year. In 1999, lives saved are calculated using the white population aged 45–54 in 1999 (): . In 2000, lives saved are calculated based on the population that would have been observed if lives had been saved in 1999, net of those who would have died of other causes in 1999, who had not aged out of the group 45–54,

| [S1] |

where . For year t, we construct the population from which lives would have been saved if the mortality rate had continued to fall at 1.8% per year, and calculate lives saved in year t as in Eq. S1.

The temporal associations between suicide and poisoning mortality and morbidity are established for each of our morbidity markers using least squares regressions with census region fixed effects. For census region i in year t, we ran least squares regressions of suicide and poisoning mortality combined,

With the exception of neck pain and facial pain, we find a significant association between suicide and poisoning mortality and morbidity for each morbidity marker presented in Table 2.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Cutler, Jonathan Skinner, and David Weir for helpful comments and discussions. A.C. acknowledges support from the National Institute on Aging under Grant P30 AG024361. A.D. acknowledges funding support from the National Institute on Aging through the National Bureau of Economic Research (Grants 5R01AG040629-02 and P01AG05842-14) and through Princeton’s Roybal Center for Translational Research on Aging (Grant P30 AG024928).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Commentary on page 15006.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1518393112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cutler DM, Deaton A, Lleras-Muney A. The determinants of mortality. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20(3):97–120. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deaton A. The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee RD, Carter LR. Modeling and forecasting U.S. mortality. J Am Stat Assoc. 1992;87(419):659–671. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980−2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutler DM. Your Money or Your Life: Strong Medicine for America’s Health Care System. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manton KG, Gu X. Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in the United States black and nonblack population above age 65 from 1982 to 1999. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(11):6354–6359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutler DM. The reduction in disability among the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(12):6546–6547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131201698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman VA, Schoeni RF, Martin LG, Cornman JC. Chronic conditions and the decline in late-life disability. Demography. 2007;44(3):459–477. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoeni RF, Freedman VA, Martin LG. Why is late-life disability declining? Milbank Q. 2008;86(1):47–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin LG, Freedman VA, Schoeni RF, Andreski PM. Health and functioning among baby boomers approaching 60. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(3):369–377. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: A ten-year trend. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):15–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States, 2014: With Special Feature on Adults Aged 55−64. U.S. Gov Printing Off; Washington, DC: 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preston SH. An international comparison of excessive adult mortality. Popul Stud (Camb) 1970;24(1):5–20. doi: 10.1080/00324728.1970.10406109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):1981–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips JA. A changing epidemiology of suicide? The influence of birth cohorts on suicide rates in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;114(Aug):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips JA, Robin AV, Nugent CN, Idler EL. Understanding recent changes in suicide rates among the middle-aged: Period or cohort effects? Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5):680–688. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper S, Rushani D, Kaufman JS. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap, 2003−2008. JAMA. 2012;307(21):2257–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health . In: Risk Factors for Suicide: Summary of a Workshop. Goldsmith SK, editor. Natl Acad Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine . In: Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE, editors. Natl Acad Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: Overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers and other drugs among women—United States, 1999−2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(26):537–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—Tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beauchamp GA, Winstanley EL, Ryan SA, Lyons MS. Moving beyond misuse and diversion: The urgent need to consider the role of iatrogenic addiction in the current opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2023–2029. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control . Policy Impact, Prescription Painkiller Overdoses. Centers Dis Control; Atlanta: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinones S. Dreamland: the True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic. Bloomsbury Press; New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: A retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(7):821–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(20):1943–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou R, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: A systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276–286. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheatle MD. Depression, chronic pain, and suicide by overdose: On the edge. Pain Med. 2011;12(Suppl 2):S43–S48. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips JA, Nugent CN. Antidepressant use and method of suicide in the United States: Variation by age and sex, 1998−2007. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):360–372. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.785373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries. Org Econ Coop Dev; Paris: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samwick AA, Skinner J. How will 401(k) pension plans affect retirement income? Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(1):329–343. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Social Security Administration (2015) Research, statistics, and policy analysis. Available at www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/. Accessed September 13, 2015.

- 33.Autor DH, Duggan MG. The growth in the Social Security Disability rolls: A fiscal crisis unfolding. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20(3):71–96. doi: 10.1257/jep.20.3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liebman JB. Understanding the increase in disability insurance benefit receipt in the United States. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29(2):123–150. doi: 10.1257/jep.29.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun S, Coglianese J, Furman J, Stevenson B, Stock J. 2015 Understanding the decline in the labor force participation rate in the United States. Available at www.voxeu.org/article/decline-labour-force-participation-us. Accessed June 21, 2015.

- 36.Meier B. April 9, 2012. Tightening the lid on pain prescriptions. NY Times, Section A, p 1.

- 37.Rostron BL, Boies JL, Arias E. 2010. Education Reporting and Classification on Death Certificates in the United States. Vital and Health Statistics (Natl Cent Health Stat. Atlanta) Ser 151, Vol 2. [PubMed]

- 38.Kessler RC, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mayo Medical Clinic (2015) Test ID: AST. Available at www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Clinical+and+Interpretive/8360, www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Clinical+and+Interpretive/8362. Accessed August 17, 2015.