Abstract

Background:

There is growing recognition of patient rights in health sectors around the world. Patients’ right to complain in hospitals, often visible in legislative and regulatory protocols, can be an important information source for service quality improvement and achievement of better health outcomes. However, empirical evidence on complaint processes is scarce, particularly in the developing countries. To contribute in addressing this gap, we investigated patients’ complaint handling processes and the main influences on their implementation in public hospitals in Vietnam.

Methods:

The study was conducted in two provinces of Vietnam. We focused specifically on the implementation of the Law on Complaints and Denunciations and the Ministry of Health regulation on resolving complaints in the health sector. The data were collected using document review and in-depth interviews with key respondents. Framework approach was used for data analysis, guided by a conceptual framework and aided by qualitative data analysis software.

Results:

Five steps of complaint handling were implemented, which varied in practice between the provinces. Four groups of factors influenced the procedures: (1) insufficient investment in complaint handling procedures; (2) limited monitoring of complaint processes; (3) patients’ low awareness of, and perceived lack of power to change, complaint procedures and (4) autonomization pressures on local health facilities. While the existence of complaint handling processes is evident in the health system in Vietnam, their utilization was often limited. Different factors which constrained the implementation and use of complaint regulations included health system–related issues as well as social and cultural influences.

Conclusion:

The study aimed to contribute to improved understanding of complaint handling processes and the key factors influencing these processes in public hospitals in Vietnam. Specific policy implications for improving these processes were proposed, which include improving accountability of service providers and better utilization of information on complaints.

Keywords: Patient rights, patient complaint, Vietnam

Background

Patient complaint procedures are a way to receive feedback from patients, and are recognized as an important tool for improving service quality within the health sector.1–3 Patients often complain when they are dissatisfied with a service they have received, and specific causes of complaints typically relate to professional conduct, provider–patient communication, treatment and care of patients, medical errors, malpractice, lack of skills, waiting for care and costs.4–8 Complaints may vary in severity, from patients’ concerns not being listened to, the most common complaint, to some form of loss, to death as a result of poor care.3,8

Patients’ complaints can provide a useful source of information for monitoring the quality of care. However, in order for patients’ complaints to be effectively utilized, there needs to be a systematic channel to collect and analyse information. Analysis of patient complaint data in countries such as the United States, Finland, France and Sweden has provided valuable information on the source of medical errors, leading to suggestions to improve patient safety.6–9

To facilitate responsiveness to patients’ complaints and capture valuable feedback, several regulations on handling complaints have been developed and implemented in many different healthcare systems, for example, in the United States, the United Kingdom, Finland, France, Sweden and Taiwan. Although processes of complaint handling vary between countries, the complaint channels for unsatisfied users typically include approaching local health facilities, and subsequently appealing to higher health system levels, local authorities or other key stakeholders such as courts or insurance companies.1,4,8–11 The main factors affecting implementation of complaint processes in different contexts include the existence of clear processes and competent staff to handle complaints, as well as a degree of awareness of complaint channels and processes by service users to initiate the complaint and receive feedback from service providers.8,11–13

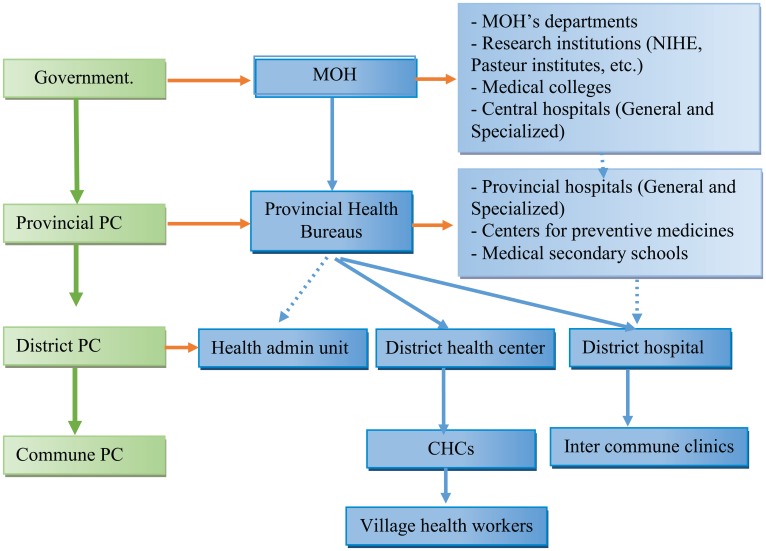

Vietnam has been a socialist market-oriented economy since 1986. Despite the achievement of becoming a middle-income country with a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of $1,160 in 2011, the country still faces a lot of challenges, such as limited policy making capacity, lack of independent regulatory bodies, conflicts of interest and wide spread corruption.14 As shown in Figure 1, the health system in Vietnam comprises national, province, district and commune levels.

Figure 1.

Health system in Vietnam.

PC: people committee; CHC: commune health centers.

Vietnam has passed legislation addressing patients’ complaints, alongside establishing channels for handling complaints. In 1992, the general right to complain was set out in the Constitution in 199215 and the Law on Complaints and Denunciation (hereon, the Law on Complaints), which was passed in 1998 and amended in 2004 and in 2005.16–18 The Law enabled all citizens in Vietnam to complain about any publicly provided service. The Law aims to legitimize the consumer rights of citizens, agencies and organizations, and since 2005 lawyers and courts have been allowed to be involved in complaint cases. In 2005, the Ministry of Health (MOH)19 translated these Laws into detailed guidelines for implementation within the health sector through Decision N44/2005 (MOH regulation on complaints), which aimed to guide complaint handling within the healthcare sector.

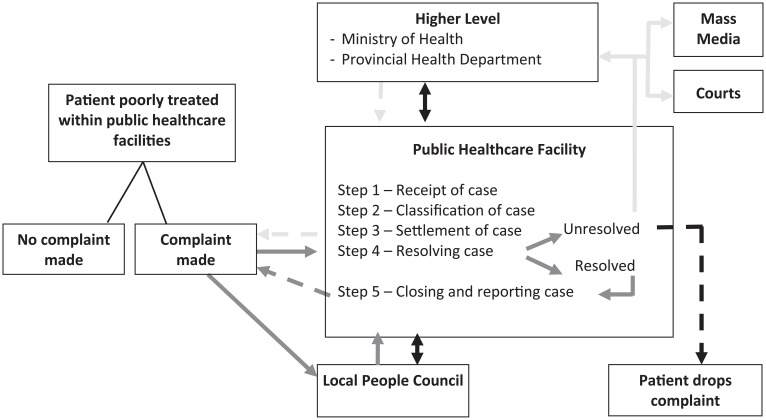

Within the MOH regulation, there are four areas under which complaints can be made: quality of medicines, hygiene and food safety, medical examination and treatment, and socio-economic areas such as staff salaries and allowances. The MOH regulation introduced additional steps for verifying causes of complaint cases and stated that complaints should be pursued and resolved by a healthcare facility through a meeting with family and patients, or by setting up a committee to review complaint cases. As shown in Figure 2, there are five steps for handling complaints related to public healthcare facilities in Vietnam. These are as follows: (1) receipt of the case, (2) classification of the case, (3) settlement of the case, (4) resolution of the case and (5) reporting on and closing the case. The above relates solely to the public sector and complaints against private healthcare providers are regulated by a separate legislation, the Ordinance on Private Medical and Pharmaceutical Practice.20 More recently, the 2009 Law on Examination and Treatment included one chapter on patients’ right to complain, denunciate and settle on medical examination and treatment that applied to both public and private health sectors.21

Figure 2.

Complaint handling procedures.

Most literatures available on complaint processes related to health services are from high-income countries. This article contributes to a better understanding of complaint handling practices in developing countries, using Vietnam as the case study. The aim of the study was to better understand the complaint handling processes, and the key factors influencing these processes, in public hospitals in Vietnam.

Methods

The study was conducted in two provinces, representing the two main regions of Vietnam (North and South) between November 2010 and August 2011. The provinces, each having a population between 1.6 and 11.7 million people, respectively, were identified in discussions with the MOH and were chosen on the basis of similar maternal and child health indicators (mortality and morbidity) and GDP in province. In each province, two districts and two communes per district were randomly chosen.

A mixed method approach was used involving two data collection methods: document review and in-depth interviews with key informants. A total of 50 documents, both hard and electronic copies, were reviewed. All documents from government, MOH and provincial levels which provided a written record of different aspects of complaints (i.e. number, level and types of complaints) were reviewed. MOH and provincial reports also provided trends in key hospital services in the area of maternal health in the 5-year period since the introduction of the MOH regulation (2006–2010), such as number of normal birth deliveries, C-sections and maternal deaths.

Key informants for in-depth interviews were chosen based on their knowledge, experiences and position related to complaint processes at different levels and positions at provincial and district levels. The purposefully selected key informants included the following: (1) key administrators in charge of complaint administration at provincial health departments and district health offices, (2) key officers who handled complaints at each hospital and (3) health service users at provincial and district hospitals and complainants at district hospitals. A total of 34 interviews were conducted using a broad topic guide which aimed to identify the degree of respondent’s awareness of the complaint handling processes (i.e. respondents were asked to describe the complaint processes), as well as to understand the respondent’s experiences and views in relation to the processes (i.e. respondents were asked to reflect on their own experiences and roles in relation to the health system’s strengths and weaknesses). Informed consent was obtained from all respondents and all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

A framework approach was used to analyse the data using the study conceptual framework and aided by qualitative data analysis software (Nvivo v7). The conceptual framework drew on Walt and Gilson’s22 policy triangle, which in addition to policy content, distinguishes how policies are made (i.e. processes), by whom (i.e. actors), within what environment (i.e. context). The data from all sources were continuously triangulated throughout the analysis process, which was conducted by at least two researchers, to ensure validity and reliability of findings. Ethical approval (No. 047/2010/YTCC-HD3) for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Hanoi School of Public Health.

Results

In this section, an overview of the complaint handling system in public hospitals in Vietnam is provided, followed by identification of key factors influencing procedures for collecting and handling patient complaints.

Complaint handling in public hospitals in Vietnam

Data on complaints from 2006 to 2010 in the health system and two provinces are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Complaint handling within the health system in Vietnam 2006–2010.

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of provinces which submitted complaint reports to MOH | 40 | 32 | 53 | 45 | 42 |

| Total number of complaint cases in health sector | 570 | 539 | 2219 | 275 | 1,300 |

| Number of cases in Northern province | 52 | 38 | 36 | 28 | 18 |

| Number of cases in Southern province | 13 | 38 | 19 | 17 | 33 |

| Categories of complaint cases in health system as percentage of total | |||||

| % Examination and treatment | 45.2 | 48.0 | 53.1 | 26.8 | 42.6 |

| % Quality of drugs | 5.0 | 3.3 | 4.6 | 6.6 | 4.3 |

| % Socio-economic | 46.5 | 46.3 | 39.2 | 60.2 | 48.7 |

| % Food safety | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 6.4 | 4.4 |

| Percentage of complaint cases under MOH responsibility for handling | 17.9 | 25.6 | 22.0 | 30.5 | 30.9 |

| Percentage of complaint cases under PHD responsibility for handling | 71.0 | 53.9 | 59.1 | 61.0 | 59.0 |

MOH: Ministry of Health. PHD: Province Health Department

Source: MOH and PHD inspection reports from the two Provinces 2006-2010.

Analysis of both documents and interview data revealed that complaint cases in the health system in Vietnam are categorized into four groups, as denoted in the MOH regulation on complaints. The areas that received the highest proportion of complaint cases included medical examination and treatment, in addition to socio-economic issues (Table 1). While data for hospitals are not disaggregated from the overall health system, within the hospitals in our study, we found the consistent trend that most complaints were related to areas of medical examination and treatment, such as poor attitudes of health providers, including being rude, unresponsive behaviour, poor hospital environment (such as dirty, non-functioning bathrooms), medical complications and deaths.

Due to the perceived sensitivity of this topic by both health staff and affected service users, the research team could not collect the total number of complaint cases that occurred at each hospital. However, it appears that in all public hospitals, very few written complaints were received, which possibly explains the generally low number of reported complaints in the country. According to the implementers of this regulation (i.e. officers handling complaints), feedback was typically expressed through face-to-face meetings, a telephone hotline with hospital staff or weekly patient council meetings in the hospital. As a result, most cases were not recorded in the system and were not reported to a higher level such as the Province Health Department (PHD) and the MOH.

The interviews with administrators also confirmed that the number of complaints included in the MOH and PHD reports contained only the cases that they received in the office, which were mostly the cases referred from the lower level. The number is therefore low, varying from 13 to 52 cases per year in each province. Among these cases, the proportion that the MOH and PHD are actually responsible for handling was not very high, about 30% at MOH level and 50%–60% at PHD level (Table 1). Within each hospital, the director is ultimately responsible for the handling of all complaint cases. However, respondents indicated that the process of implementation varies between hospitals: the directors may either manage the complaint process themselves or assign this task to another person, typically within the Department of Personnel or Planning Department.

In handling a complaint case, a team, often comprising hospital managers, members of labour unions, nurse managers and technical experts, is usually established to review the case and meet with the patients and their families. Although the establishment of a professional committee was felt by interviewees to be sometimes necessary to verify the context of complaint cases, this was difficult to set up in remote areas due to unavailability of qualified experts. According to the administrators and implementers, disciplinary actions (where complaints are justified) can be applied differently by different public healthcare facilities. The most common disciplinary actions included moving staff to another post, making a formal reprimand in staff meetings and reducing monthly and/or yearly bonuses. However, application of penalties was constrained by the difficulty in providing conclusive evidence of cases when health providers were rude and the low capacity of health providers to enforce sanctions.

According to the regulatory documents, in addition to the above channels, patients may send their grievances directly to the People Councils at different levels, which are directly related to the governments at provincial, district and commune levels. The local People Council is elected by the people to represent them within the government. It organizes periodic meetings, informs staff about the complaints received and obtains an official response from the public health facilities, which makes the final decision regarding the grievance. According to regulation administrators and implementers, this channel is effective as the People Council, while not making formal decisions, has influence within local government, for example, in relation to healthcare resource allocation. Therefore, health facilities normally review the feedback from the local People Council and respond to any negative comments in writing.

In all studied hospitals, few cases were sent up to a higher level (PHD and MOH levels) or to the mass media, and no cases were reported which involved courts and lawyers. The main reasons noted by interviewees included the following: lack of access to mass media due to high costs and lack of personal contacts, lack of culture to use legal services in Vietnam, possibly due to the high costs, and reluctance of health facilities to involve lawyers in complaint processes, as this would make the process much more complicated.

Factors influencing procedures for collecting and handling patient complaints in public hospitals

As stated above, despite the existence of detailed and documented procedures for collecting and handling complaints, variations were found between hospitals in the implementation of these procedures. These variations were due to the following four factors influencing the patient complaint processes: (1) insufficient investment in complaint handling procedures, (2) limited monitoring of complaint processes, (3) patients’ low awareness of, and perceived lack of power to change, complaint procedures and (4) autonomization pressures on local health facilities. Each is discussed in greater detail below.

Insufficient investment in complaint handling procedures

Interviews showed that there were insufficient resources for handling patients’ complaints at all levels. In 2010, there were a total of 70 health inspectors in the MOH inspectorate unit and about 5 in each inspectorate unit of the PHDs. Health inspectors were trained in the state school of inspectors; however, they have many other duties besides handling complaints, such as inspection of other health services at different levels. Furthermore, the inspectors receive little occupational allowance to cover the expenses for their work. As a result, there are no sufficient resources, or motivation, for them to go to the field to handle cases:

At this stage, there is no regulation on official payment to inspectors. Payment for inspectors is various, depending on the local decision. If the director feels it is necessary, inspectors can be paid extra from office funding (reporting etc.); or get an allowance for field trips [undertaken for verifying cases], but these payments are very low, not enough for beef noodle soup (Regulation developer).

At the provincial level, there was training for provincial state inspectors on the implementation of the wider Law on Complaints. However, there was no specific training for the implementation of the MOH regulation, which specifically guides handling complaints within the healthcare sector. Lack of financial support was given as the reason for the absence of specific orientation or training on the implementation of the MOH regulation. In practice, this meant that no respondents were able to name the MOH regulation and only the less specific Law on Complaints was used, as the following respondent reflected:

The main policy document used for solving complaint cases here was not the MOH regulation on complaints. We used Law on Complaints instead (Regulation Administrator, Northern Province).

At the hospitals, there was no full-time position for handling complaints. Complaint handling was often assigned to a medical professional working in the Personnel or Planning Department. According to respondents, the complaint handlers were often busy with many other tasks and did not see complaint handling as part of their core professional duties. In addition, there was no training to learn important skills associated with handling complaints, such as communication, and most complaint handlers acquired these skills from colleagues:

Required skills from those actors include: collaboration, loyalty, accountability of each person and capacity of the inspector to get information from the relevant people – knowing how to ask the question to get the answers – and knowledge of the local context (because the people might be too tired; or might not want to answer). Only learned from the colleagues who are doing similar works before (Regulation Developer).

Limited monitoring of complaint processes

Limited monitoring of complaint processes was found within the public healthcare facilities, due largely to poor feedback loops at all levels. The possible feedback loops for handling complaints included the following: supervision visits from the MOH to the PHD, supervision visits from the PHD to health facilities at the lower level, submission of complaint reports and evaluation of patient complaint handling activities. However, according to health inspectors in the MOH and PHD, no formal evaluation of complaint handling activities has yet been conducted. Furthermore, there was no regular supervision of complaint handling within the health system, due to the lack of inspectors, as well as lack of financial provisions for supervision visits including travel costs and allowances:

[There is a] lack of budget for petrol for supervision visits. Therefore, we could not organise the visits to lower levels as planned (Regulation Administrator, Northern Province).

The grievance redressal agenda was often combined with other supervision visits such as visiting private facilities. According to one informant, only one visit was conducted per institution each year by the PHD. However, special attention was paid to institutions with frequent complaint cases or those with cases awaiting a response within the required deadline. Additional visits or telephone calls with those institutions were used, which focused specifically on resolving the complaint cases and improving staff knowledge and skills related to complaints. Where needed by facilities when, for example, they were unable to resolve a complaint, the provincial inspectors were invited to join such visits. In such cases, the supervision visits had a dual purpose: both inspecting (i.e. monitoring) and supportive (i.e. to prevent further rise in complaint cases).

The MOH and PHD Inspectorate units require each healthcare facility to report annually on the complaint cases resolved at the facility. However, analysis of MOH inspectorate reports revealed that in the last 5 years on average, only about two-thirds of PHDs submitted annual reports to the MOH (Table 1). At the time of our research, no sanctions were implemented for failure to submit reports. The reports that were submitted lacked information on how the cases were resolved and included only written complaints. As mentioned earlier, the cases that were concluded verbally between providers and service users were not recorded by the hospitals and not reported to a higher level.

Patients’ low awareness of, and perceived lack of power to change, complaint procedures

Although the Law on Complaints and the MOH regulation on handling complaints are used for handling patients’ complaints, there is evidence of patients’ limited awareness of, and willingness to utilize, complaint procedures. Interviews with service users in the hospitals revealed that they did not know about the Law on Complaints or the MOH regulation on handling complaints. However, most users knew how to express their complaints through different channels, such as meeting the Hospital Director or person in charge:

I know that I should first go to the director of hospital. If the case is not solved, then I will go to the provincial department of legislation, and VTV1 (Vietnamese TV station). I know that I could ask for the hotline telephone to find out how to make a complaint. I know that doctors love their patients and they will tell me this information. I do not know about our Law on Complaint (Patient, Southern Province).

One cultural influence, which emerged in our analysis, relates to patients’ perceptions of their lack of power within society. For example, the complainants of two cases with newborn deaths reported that they were not happy with the hospitals’ reporting of the deaths as no causes were identified, and the only explanation given was the limited skills of health providers. In addition, the modest compensation provided did not cover the costs of the treatment incurred. However, the complainants accepted the conclusion because they believed they were ‘low-status’ families, who could not take the case to a higher level:

It was nothing compared to the costs paid to the hospital (provincial – national level). The man asked to remove the GR complaint letter and later they sent the feedback to tell that all faults are family related. This caused us to be angry. We cannot do much because we are very low (Patient, Northern Province).

This suggests that the complainants, despite their disagreement with the hospitals’ decisions following their complaints, felt powerless to take their complaints further in the system, for example, to appeal against the initial hospital decision. Our analysis revealed that this was mainly due to their perception that their low social status would likely prevent their voices from being heard at the higher levels of the system.

Autonomization pressures on local health facilities

The Government of Vietnam introduced autonomization of health facilities in 2002. Public healthcare facilities were given autonomy in service provision, human resource allocation and financial budgeting, while the government budget was reduced. One practical outcome of autonomization appears to be the emerging culture of pressure on public healthcare facilities to protect their reputation, in order to generate income through attracting patients to use their services. Interviewees pointed out that public institutions, for this reason, often resolve complaint cases locally, and only a few cases which could not be negotiated go up to a higher level. As a result, as cases at the local level tend to be resolved verbally through negotiation, mediation and compensation, the step of verifying, recording and preventing the causes of cases is easily missed:

Very few complaint cases go to the higher level since the hospitals try to solve the case themselves by offering compensation. The hospital sees the needs of patients in terms of compensation, and where they can pay to solve the case, they do. However, public institutions do not have a clear compensation level, so if for this reason the case cannot be solved, then the case does go up to the next level (Regulation Administrator, Southern Province).

Autonomization pressures provide clear incentives for health facilities to resolve complaints locally. These institutional pressures also appear to undermine the achievement of an underlying purpose of patient complaints, that is, to provide evidence for improvement of service delivery practices in health facilities. Instead, health providers are likely to regard patient complaints as a nuisance or a potential threat to their financial situation, rather than useful evidence for improving quality of services.

Having identified the factors contributing to the variations between formal processes and actual practices, next we discuss our findings and propose the main policy implications for improving complaint processes in Vietnam and beyond.

Discussion

From the above findings, two issues emerge for discussion. First, while the existence of complaint handling processes is evident in the health system in Vietnam, utilization was often limited. Second, different factors were found to constrain the implementation and use of complaint regulations.

The findings showed the existence of favourable conditions for implementation of a complaint handling system.1,3,4,7 First, the notion of patients’ rights to complain in Vietnam, brought into the health sector since Doi Moi in 1986, was officially recognized in the Constitution in 1992. More recently, the legislation on grassroots democratization was introduced to improve transparency and prevent corruption and may have contributed to the increase in reported number of complaints. However, the sustained success of this legislation appears problematic because of bureaucratic politics.23

Second, the principles of complaint handling procedures in Vietnam are similar to the systems in some high-income countries such as Finland, the United Kingdom, Sweden, France and Holland and include similar stages: appealing to local facilities, higher levels within health system or local authority and/or other stakeholders such as courts and insurance centres.1,8,9,11,24 In Vietnam, however, most complaint cases are solved within hospitals and, as a result, there are low numbers of reported complaints. A neutral body like an Ombudsman in Finland,11 or a quasi-independent body such as a patient advisory committee in Sweden,9 could make the complaint handling process more independent and represents a possible next step in further improvement of the complaint system.

Several factors constrained the implementation of the complaint system, including limited use of channels outside the health system, such as media and courts. In high-income countries such as Holland and Finland, these channels can be effective ways of drawing attention to service quality issues.6,24 In comparison, the practice of using these channels in Vietnam is new.25 Patients in Vietnam often have limited knowledge on complaint processes, especially procedures for appealing against decisions, and lack of contacts and lack of resources required for higher levels, such as courts or media, can make patients feel ‘powerless’ in the complaint process, forcing them to accept the hospitals decision. Välimäki et al.11 state the importance of increasing patients’ knowledge about their rights, which can be done when the patient receives information about their illness and its treatment. In France, after the introduction of a Law on patient’s rights, an increase in the number of complaints in hospitals indicated an increase in awareness of patients on their rights regarding medical issues.8 It is therefore important that patients are educated on how to access and use complaint processes, possibly as part of their education on their rights.

Most of the complaints in our study were related to areas of medical diagnosis and treatment, medical complications and deaths, which were similar to other countries such as the United States and Sweden. Patients’ feedback can be an important tool for quality improvement1–3 and failure to use complaint data for quality improvement can be regarded as a potential failure of the overall health system.10 In 2012, the MOH emphasized the need to use the results of patients’ feedback and complaints for quality improvement of medical services in Vietnam.26 So far in Vietnam, however, the role, voice and participation of patients and community in service quality improvement remain limited.26 The findings showed a low number of recorded patient complaints within public hospitals in Vietnam, which is possibly due to the pressures on health facilities to resolve cases quickly and locally in order to protect their income and reputation. Without recorded formalized complaints, health authorities (MOH and PHD) are unable to use complaint data to improve poor medical diagnosis and treatment, which can result in increased incidences of morbidity and mortality within public hospitals.

The insufficient investment of resources (finance and competent and motivated staff) in complaint procedures was also found to constrain the implementation of complaint processes. A study in Taiwan also found a lack of competent complaint handlers within a hospital setting to be a constraint.12 Sufficient resources need to be devoted to complaint processes, especially within hospitals where there is opportunity to use complaint data for service quality improvement.

Finally, one potential influencing factor, which was omitted by our respondents, though documented by other studies in Vietnam, is corruption within the health sector, often related to informal payments and cost of medicines.27 Since economic reforms in 1986, corruption has become a severe problem in Vietnam and can be seen as part of the economic transition process. The country’s rapid economic growth ‘expands corruption opportunities faster than accountability mechanisms manage to follow’.28 The roots and manifestations of corruption are multiple29 and include the following: (1) abuse of power by public officials, (2) arbitrary decisions related to policies and administration, (3) weak accountability of officials and government agencies and (4) weak state implementation and monitoring.30 In healthcare settings, these causes may also relate to the close professional relations between those who enforce and implement regulations – effectively colleagues – within the health system. To avoid such situations, strengthening monitoring procedures, complaint systems and audit functions within the health system need to receive increased attention.27

Policy implications for improving complaint handling systems

This study identified a number of factors that influenced the procedures for collecting and handling patient complaints in public hospitals in Vietnam, affecting the number of recorded complaints collected, and how the causes of those complaints were addressed. Without the incentive for and ability to collect good quality and complete patient complaint datasets, health authorities will be unable to implement evidence-based improvements within public hospitals. It is therefore important that mechanisms are put in place to strengthen patient complaint handling systems.

A number of potential policy implications for improving the complaint handling system in Vietnam and other similar settings can be derived from the earlier discussion. These are as follows: (1) improving the processes for complaint handling by considering a neutral body, (2) strengthening the monitoring of complaints processes and utilizing the results for quality improvement of medical services, (3) raising awareness of service users of complaint handling procedures, (4) ensuring the existence of sufficient resources for complaint handling systems and (5) maintaining a high level of knowledge and skills of relevant staff in relation to complaint handling procedures. Further research on patients’ complaints in Vietnamese health system, specifically on the role of patients’ complaints in improving quality of health care, would be important to inform policy change in the country. In the longer term, enhancing the role of civil society organizations in the health system to support service users in their attempts to communicate their complaints, and ensure better accountability of service providers, can also contribute to improved utilization of patient complaints for quality improvement within the healthcare sector within Vietnam and beyond.

Conclusion

This study aimed to contribute to improved understanding of complaint handling processes and the key factors influencing these processes in public hospitals in Vietnam. While the existence of complaint handling processes is evident in the health system, their utilization was often limited. Four groups of factors were found to constrain the implementation and use of complaint regulations, which included health system–related factors as well as social and cultural influences. Specific policy implications for improving complaints handling processes were discussed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank colleagues at the Hanoi School of Public Health and all Health Stewardship and Regulation in Vietnam, India and China (HESVIC) partners for their contributions during the HESVIC project.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: All authors contributed significantly in all phases of the project in accordance with uniform requirements established by International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and contributors who do not meet authorship criteria are listed in acknowledgements. B.T.T.H.: participated in design of study, carried out the study and drafted the article; T.M.: participated in design of study, reviewed and edited the article; R.M.: reviewed and edited the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The HESVIC project was funded by the European Commission’s Framework Seven (EC FP7), grant number 222970.

References

- 1. Holmes-Bonney K. Managing complaints in health and social care. Nurs Manag 2010; 17(1): 12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hsieh SY. An exploratory study of complaints handling and nature. Int J Nurs Pract 2012; 18: 471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Natangelo R. Clinicians’ and managers’ responses to patients’ complaints: a survey in hospitals of the Milan area. Clin Govern Int J 2007; 12: 260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dagher M, Kelbert P, Lloyd R. Effective ED complaint management. Nurs Manage 1995; 26: 48B–48D, 48F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jimenez-Corona M-E, Ponce-De-Leon-Rosales S, Rangel-Frausto S, et al. Epidemiology of medical complaints in Mexico: identifying a general profile. Int J Qual Health Care 2006; 18(3): 220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuosmanen L, Heino R, Suominen S, et al. Patient complaints in Finland 2000–2004: a retrospective register study. J Med Ethics 2008; 34(11): 788–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Montiny T, Noble AA, Stelfox HT. Content analysis of patient complaints. Int J Qual Health Care 2008; 20: 412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giugliani C, Gault N, Fares V, et al. Evolution of patients’ complaints in a French university hospital: is there a contribution of a law regarding patients’ rights? BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jonsson PM, Øvretveit J. Patient claims and complaints data for improving patient safety. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2008; 21: 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hsieh SY. The use of patient complaints to drive quality improvement: an exploratory study in Taiwan. Health Serv Manage Res 2010; 23: 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Välimäki M, Kuosmanen L, Kärkkäinen J, et al. Patients’ rights to complain in Finnish psychiatric care: an overview. Int J Law Psychiatry 2009; 32: 184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsieh SY. Factors hampering the use of patient complaints to improve quality: an exploratory study. Int J Nurs Pract 2009; 15: 534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuzu N, Ergin A, Zencir M. Patients’ awareness of their rights in a developing country. Public Health 2006; 120: 290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Bank. Vietnam 2012, http://data.worldbank.org/country/vietnam (accessed 18 June 2012).

- 15. The National Assembly. Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Government of Vietnam, Hanoi, Vietnam, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16. The National Assembly. Law on complaints and denunciations (No. 09/1998/QH10). Government of Vietnam, 1998, http://www.moj.gov.vn/vbpq/en/Lists/Vn%20bn%20php%20lut/View_Detail.aspx?ItemID=1265 [Google Scholar]

- 17. The National Assembly. Law on solving complaints and denunciation (amended). Government of Vietnam, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18. The National Assembly. Law: amending and supplementing a number of articles of the Law on complaints and denunciations (No. 58/2005/QH11). Government of Vietnam, 2005, http://moj.gov.vn/vbpq/en/Lists/Vn%20bn%20php%20lut/View_Detail.aspx?ItemID=5964 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ministry of Health. Regulation on settlement of complaints in the field of health (No. 44/2005/QD-BYT). Government of Vietnam, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20. The National Assembly. Ordinance on private medical and pharmaceutical practice (No. 07/2003/PL-UBTVQH11). Government of Vietnam, 2003, http://www.moj.gov.vn/vbpq/en/Lists/Vn%20bn%20php%20lut/View_Detail.aspx?ItemID=8910 [Google Scholar]

- 21. The National Assembly. Law on medical examination and treatment (No. 40/2009/QH12). Government of Vietnam, 2009, http://www.moj.gov.vn/vbpq/en/Lists/Vn%20bn%20php%20lut/View_Detail.aspx?ItemID=10471 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan 1994; 9(4): 353–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fritzen SA. Legacies of primary health care in an age of health sector reform: Vietnam’s commune clinics in transition. Soc Sci Med 2007; 64: 1611–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van der Wal G, Lens P. Handling complaints in hospitals. Health Policy 1994; 31: 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gainsborough M. Corruption and the politics of economic decentralization in Vietnam. J Contemp Asia 2003; 33(1): 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministry of Health, Health Partnership Group. Joint annual health review 2012: improving quality of medical services, 2012, http://jahr.org.vn/downloads/JAHR2012/JAHR2012_Eng_Full.pdf?phpMyAdmin=5b051da883f5a46f0982cec60527c597

- 27. Taryn V, Brinkerhoff D, Feeley FG, et al. Confronting corruption in the health sector in Vietnam: patterns and prospects. Public Adm Dev 2012; 32: 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fritzen S. Beyond ‘political will’: how institutional context shapes the implementation of anti-corruption policies. Pol Soc 2005; 24(3): 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huss R, Green A, Sudarshan H, et al. Good governance and corruption in the health sector: lessons from the Karnataka experience. Health Policy Plan. Epub ahead of print 17 December 2010. DOI: 10.1093/heapol/czq080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nguyen TT, Van Dijk MA. Corruption, growth, and governance:private vs. state-owned firms in Vietnam. J Bank Financ 2012; 36: 2935–2948. [Google Scholar]