Objective:

To evaluate short-term outcomes of a new treatment for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis in a randomized controlled trial.

Background:

Perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis (Hinchey III) has traditionally been treated with surgery including colon resection and stoma (Hartmann procedure) with considerable postoperative morbidity and mortality. Laparoscopic lavage has been suggested as a less invasive surgical treatment.

Methods:

Laparoscopic lavage was compared with colon resection and stoma in a randomized controlled multicenter trial, DILALA (ISRCTN82208287). Initial diagnostic laparoscopy showing Hinchey III was followed by randomization. Clinical data was collected up to 12 weeks postoperatively.

Results: Eighty-three patients were randomized, out of whom 39 patients in laparoscopic lavage and 36 patients in the Hartmann procedure groups were available for analysis. Morbidity and mortality after laparoscopic lavage did not differ when compared with the Hartmann procedure. Laparoscopic lavage resulted in shorter operating time, shorter time in the recovery unit, and shorter hospital stay.

Conclusions:

In this trial, laparoscopic lavage as treatment for patients with perforated diverticulitis Hinchey III was feasible and safe in the short-term.

Keywords: diverticolitis, Hartmann, laparoscopy, lavage, morbidity

Perforated diverticulitis of the colon is an uncommon serious abdominal condition, and perforation with purulent peritonitis (Hinchey III)1 is even more uncommon.2 The traditional treatment for this group of patients has been open operation with resection of the inflamed and perforated colon with a stoma, that is, the Hartmann procedure. Considerable morbidity has been reported after the Hartmann procedure3 and many patients will never undergo secondary surgery with reversal of the stoma and restored bowel continuity.4 Less invasive types of surgical treatment have thus been considered.5–8 One such procedure is laparoscopy with abdominal lavage, which in a large prospective case series reported good results.5 However, no randomized trials have yet reported any results. As the published evidence primarily includes retrospective series,7 the need for randomized studies is obvious.

The aim of this analysis was to compare short-term results of laparoscopic lavage with the Hartmann procedure within a randomized trial “DIverticulitis—LAparoscopic LAvage vs resection (Hartman procedure) for acute diverticulitis with peritonitis” (DILALA).

METHODS

Trial Design

This trial was designed as a prospective, randomized, controlled trial (1:1) of laparoscopic lavage versus open Hartmann procedure. The protocol has previously been described in detail.9 Patients were included at 9 surgical departments in Sweden and Denmark from February 2010 to February 2014. The reports from this trial follow the CONSORT statement when applicable.10

Participants

Inclusion of patients was based on radiologic examination of the abdomen showing intra-abdominal fluid or gas and a decision to perform surgery followed by the patient's informed consent. After inclusion, patients were taken to the operating room and the procedures were commenced with a diagnostic laparoscopy.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients not possible to operate due to concomitant disease or patients participating in another randomized trials in conflict with the protocol and end-points of the DILALA trial.

When the diagnostic laparoscopy of the abdomen revealed a diverticulitis Hinchey grade III (purulent peritonitis and an inflamed part of the colon), patients were intraoperatively randomized. Patients with Hinchey grade I to II (no free fluid/pus in the abdomen), Hinchey grade IV (fecal contamination), or other pathology at laparoscopy were not eligible for randomization.

Participating hospitals were expected to screen patients for possible inclusion. The screening log was established when a hospital entered the study. All admitted patients with a diagnosis of diverticulitis according to the International Classification of Diagnosis (ICD-10) codes K57.2, K57.3, and K57.8 who underwent surgery at the included hospitals were registered in the screening log.

Research personnel assured that the block randomization sequence was followed and that clinical data entered into clinical record forms was correct. No center monitored its own data.

Interventions

Laparoscopic lavage of all 4 quadrants was performed with saline, 3 L or more, of body temperature, until clear fluid was returned. Open Hartmann procedure was performed through a midline incision. All specimens underwent pathology examination.

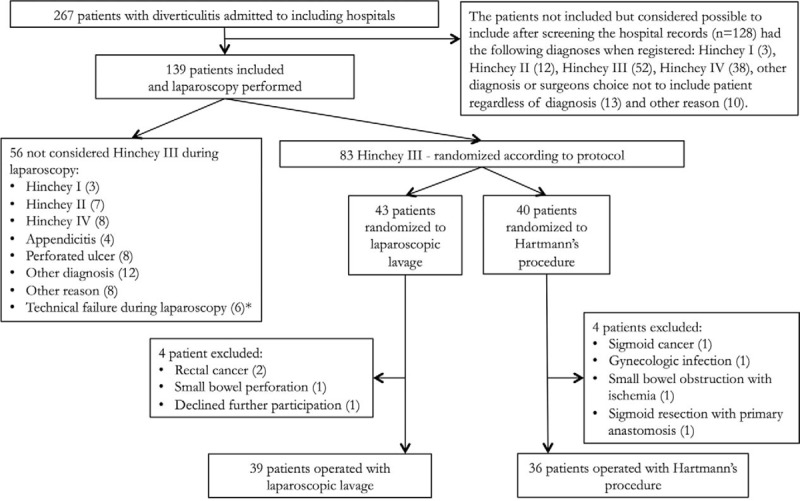

A passive drain was placed in the pelvis in all patients and left in place for at least 24 hours. Both groups were treated postoperatively according to local routines regarding antibiotic treatment, thrombosis prophylaxis and return to oral feeding. Patients were excluded after randomization because of withdrawn consent; cancer or other diagnoses than diverticulitis at surgery or during follow-up (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of patients included in the trial.

Outcomes

Four clinical record forms were filled out by the health care professionals. Baseline patient information was collected at inclusion. Details of the operative procedure as well as the postoperative phase until discharge and follow-up until 6 to 12 weeks were collected. All complications were reviewed in detail and retrospectively classified according to Clavien-Dindo,11 but to reduce the risk of misclassification, grade I and II were combined.

Primary outcome of this trial was reoperations within 12 months postoperatively, which will be reported when all patients have reached full follow-up. The present data are on short-term clinical outcomes; morbidity, readmissions, reoperations, and mortality. Additional secondary outcomes are described in the protocol article.9

Sample Size

The DILALA trial primary end-point was reoperations within 12 months. A reduction of the need for further operations of 10% in the group that has undergone laparoscopic lavage was considered clinically relevant. With a statistical power of 80% and a level of significance at 5%, randomization of 64 patients was required. Given the relatively complicated setup for the trial and that all procedures were emergency surgery, the inclusion was set to 80 randomized patients (40 + 40).

Randomization

Randomization was stratified per hospital and the patients were randomized in blocks of 10 by a professional statistician not involved in the trial.9 The allocation sequence was concealed from the staff at the participating centers by using sequentially numbered thick opaque sealed envelopes. The envelope was opened perioperatively after the operating surgeon had diagnosed the patient as having a diverticulitis Hinchey grade III. The surgeon on call (often not the local study investigator) was responsible for the perioperative randomization.

Statistical Methods

This article explores several secondary end-points in the DILALA trial: morbidity and mortality within 30 days as well as mortality within 90 days. Nonparametric statistics were used, and all results are reported as median with range or percentages in parentheses. Mann-Whitney U analysis, χ2 test, and the Fisher exact test were used where appropriate.

Ethical Aspects

This trial was approved by the Danish ethical committee (Protocol nr. H-4–2009–088) and the Ethical committee in Gothenburg (EPN Dnr 378–09). The trial was registered at ISRCTN for clinical trials ISRCTN82208287 (http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN82208287).

RESULTS

The trial included 139 patients and after diagnostic laparoscopy 83 patients were randomized. After exclusions, there were 39 patients in the laparoscopic lavage group and 36 patients in the open Hartmann's group available for analysis (Fig. 1). The screening log was returned by 6 out of 9 participating hospitals. Demographic data are shown in Table 1, and there were no obvious differences between the groups.

TABLE 1.

Demography of the Study Population

| Laparoscopic Lavage (n = 39) | Hartmann's Procedure (n = 36) | P | Missing Data Lavage/Hartmann | |

| Age | 62 (18–86) | 68 (35–88) | 0.124 | |

| Sex (women/men) | 18/21 | 21/15 | 0.292 | |

| ASA classification | 0.222 | 2 (5.1%)/3 (8.3%) | ||

| I | 7 (18.9%) | 8 (24.2%) | ||

| II | 22 (59.5%) | 13 (39.4%) | ||

| III | 8 (21.6%) | 10 (30.3%) | ||

| IV | 0 | 2 (6.1%) | ||

| BMI | 25.6 (21–32) | 24.9 (19–36) | 0.200 | 8 (20.5%)/8 (22.2%) |

| Previous diverticulitis | 5/39 (12.8%) | 5/36 (13.9%) | 0.892 | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 16/39 (41%) | 11/36 (30.6%) | 0.345 | |

| Diabetes | 2/35 (5.7%) | 2/30 (6.3%) | 0.926 | 4 (10.2%)/4 (11.1%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 18/38 (47.4%) | 15/35 (42.9%) | 0.699 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Immunosuppressants | 3/35 (8.6%) | 5/32 (15.6%) | 0.439 | 4 (10.2%)/4 (11.1%) |

The preoperative clinical characteristics of the patients were comparable between the 2 groups as shown in Table 2. There were no violations of the randomization, due to technical or other reasons. The perioperative details are reported in Table 3. Patients in the lavage group had significantly shorter operating time, almost one and a half hour (P < 0.0001). There was a difference in number of patients with a suprapubic urinary catheter (Table 3), and overall 15.8% of the patients in the lavage group did not need a urinary catheter compared to no patients in the Hartmann's group (P = 0.025).

TABLE 2.

Clinical Characteristics Preoperatively

| Laparoscopic Lavage (n = 39) | Hartmann's Procedure (n = 36) | P | Missing Data Lavage/Hartmann | |

| Leukocyte count (×109/L) | 13.6 (4–25) | 13.3 (3–22) | 0.953 | 1 (2.6%)/0 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 218 (3–530) | 177.5 (1–460) | 0.277 | 1 (2.6%)/0 |

| Body temperature (Celsius) | 37.6 (36–41) | 37.9 (37–40) | 0.737 | 4 (10.3%)/2 (5.6%) |

| Abdominal examination | 0.479 | |||

| Soft abdomen and local tenderness or palpable mass | 5/39 (12.8%) | 5/36 (13.9%) | ||

| Localized peritonitis | 16/39 (41.0%) | 12/36 (33.3%) | ||

| Generalized peritonitis | 18/39 (46.2%) | 19/36 (52.8%) | ||

| Decision base for surgery | ||||

| Computed Tomography | 38/39 (97.4%) | 35/35 (100%) | 0.340 | 0/1 (2.8%) |

| Clinical evaluation | 36/38 (94.7%) | 33/34 (97.1%) | 0.623 | 1 (2.6%)/2 (5.6%) |

| Time from decision until surgery (hh:mm) | 3:05 (1:00–13:38) | 2:51 (1:11–8:30) | 0.725 | |

TABLE 3.

Operative Data

| Laparoscopic Lavage (n = 39) | Hartmann's Procedure (n = 36) | P | Missing Data Lavage/Hartmann | |

| Duration of surgery (hh:mm) | 1:08 (0:28–3:14) | 2:34 (0:58–4:26) | <0.0001 | 4 (10.3%)/3 (8.3%) |

| Time between end of surgery and end of anesthesia (hh:mm) | 0:19 (0:05–0:42) | 0:29 (0:00–1:37) | <0.0001 | 4 (10.3%)/3 (8.3%) |

| Additional surgical procedure* | 0 | 2/36 (5.6%) | 0.368 | 4 (10.3%)/0 |

| Amount of saline used for lavage | 0.045 | 0/8 (22.2%) | ||

| No lavage | 0 | 4/28 (14.3%) | ||

| 3 L | 23/39 (59%) | 19/28 (67.9%) | ||

| 4–5 L | 9/39 (23.1%) | 4/28 (14.3%) | ||

| 6–10 L | 3/39 (7.7%) | 1/28 (3.6%) | ||

| >10 L | 4/39 (10.3%) | 0 | ||

| Inflammation site | 0.295 | |||

| Sigmoid colon | 39/39 (100%) | 35/36 (97.2%) | ||

| Rectum | 0 | 1/36 (2.8%) | ||

| Visible perforation in the colon | 2/38 (5.2%) | 18/36 (50%) | <0.0001 | 1 (2.6%)/0 |

| Presence of adhesions | 0.710 | |||

| None | 15/39 (38.5%) | 16/36 (44.4%) | ||

| Average | 20/39 (51.3%) | 18/36 (50%) | ||

| Severe | 4/39 (10.3%) | 2/36 (5.6%) | ||

| Adhesions causing technical difficulties | 8/37 (21.6%) | 5/35 (14.3%) | 0.419 | 2 (5.1%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Conversions from of randomization | 0 | 0 | ||

| Description of the Hartmann's procedure | ||||

| Location of the proximal resection margin | ||||

| Ileum† | 1/36 (2.8%) | |||

| Left colon | 14/36 (38.9%) | |||

| Sigmoid colon | 21/36 (58.3%) | |||

| Location of the distal resection margin | ||||

| Sigmoid colon | 3/36 (8.3%) | |||

| Rectosigmoid junction | 28/36 (77.8%) | |||

| Rectum | 5/36 (13.9%) | |||

| Drainage | 37/39 (94.9%) | 30/36 (83.3%) | 0.106 | 2 (5.1%)/0 |

| Urinary catheter | ||||

| Suprapubic catheter | 0/39 (0%) | 5/36 (13.9%) | 0.016 | |

| Transurethral catheter | 32/38 (84.2%) | 31/36 (86.1%) | 0.818 | 1 (2.6%)/0 |

*Loop ileostomy and appendectomy.

†Small bowel adherent to the inflamed sigmoid colon. The sigmoid colon was the most proximal resection margin on the colon, but the small bowel was also resected.

Postoperative outcomes are shown in Table 4. Patients operated by laparoscopic lavage spent significantly shorter time (median 4 hours) in the recovery unit compared with the Hartmann's group (median 6 hours; P < 0.05). Laparoscopic lavage resulted in shorter hospital stay (median 6 days) compared with the Hartmann's group (median 9 days; P < 0.05) but had a significantly longer period of abdominal drainage (median 3 vs 2 days; P < 0.05). Mortality within 30 days (3/39 vs 0/36) and 90 days (3/39 vs 4/36) did not differ significantly between the groups.

TABLE 4.

Short-term Outcome Data

| Laparoscopic Lavage (n = 39) | Hartmann's Procedure (n = 36) | P | Missing Data | |

| Time in recovery unit, h | 4 (1–12) | 6 (2–44) | 0.045 | 5 (12.8%)/4 (11.1%) |

| Required intensive care, n | 5/39 (12.8%) | 4/36 (11.1%) | 0.802 | |

| Number of days with drainage | 3 (0–21) | 2 (0–17) | 0.021 | 1 (2.6%)/7 (19.4%) |

| Blood transfusion, n | 4/39 (10.3%) | 2/36 (5.6%) | 0.453 | |

| Postoperative hospital stay, d | 6 (2–27) | 9 (4–36) | 0.037 | 1 (2.6%)/2 (5.6%) |

| Stoma related problems, n | ||||

| Skin irritation around the ostomy | N/A | 5/36(13.9%) | ||

| Difficulties learning to care for the stoma | N/A | 11/36 (30.6%) | ||

| Reoperation within 30 days, n | 5/38 (13.2%) | 6/35 (17.1%) | 0.634 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Mortality within 30 days, n | 3/39 (7.7%) | 0/36 (0%) | 0.094 | |

| Mortality within 90 days, n | 3/39 (7.7%) | 4/36 (11.4%) | 0.583 | |

| Readmission within 30 days, n | 0/38 | 2/35 (5.7%) | 0.135 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| More than 1 readmission within 30 days, n | 0/38 | 1/35 (5.7%) | 0.294 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

Reoperations and complications classified according to Clavien-Dindo11 are presented in Table 5. There were no statistical differences between the 2 groups and neither did the number of complications per patient differ between the 2 groups. Only 2 patients were readmitted.

TABLE 5.

Details on Complications and Reoperations

| Laparoscopic Lavage | Hartmann's Procedure | P | Missing Data | |

| Complications* | ||||

| Classification according to Clavien-Dindo | ||||

| Grade I and II | 17/38 (44.7%) | 13/35 (37.1%) | 0.510 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Grade IIIa | 3/38 (7.9%) | 0/35 (0%) | 0.090 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Grade IIIb | 4/38 (10.5%) | 2/25 (5.7%) | 0.455 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Grade IVa | 3/38 (7.9%) | 3/35 (8.6%) | 0.916 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Grade IVb | 1/38 (2.6%) | 1/35 (2.9%) | 0.953 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Grade V | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) | |

| No. complications per patient | ||||

| 1 | 7/38 (18.4%) | 5/35 (14.3%) | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) | |

| 2 | 8/38 (21.1%) | 7/35 (20%) | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) | |

| 3 | 1/38 (2.6%) | 1/35 (2.9%) | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) | |

| 4 | 2/38 (5.3%) | 1/35 (2.9%) | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) | |

| 5 | 2/38 (5.3%) | 0/35 (0%) | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) | |

| Reoperation within 30 days, n | 5/38 (13.2%) | 6/35 (17.1%) | 0.634 | 1 (2.6%)/1 (2.8%) |

| Type of reoperation | ||||

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 2 | 1 | ||

| Retained drainage (required laparoscopy) | 1 | 0 | ||

| Perforation of the colon (Hinchey IV) | 1 | 0 | ||

| Suspicion of bleeding | 1 | 0 | ||

| Stoma complication | 0 | 2 | ||

| Persistent peritonitis (no new findings after surgery)† | 0 | 1 | ||

| Haematoma (and inguinal hernia) | 0 | 1 | ||

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 | ||

*A patient can have more than one complication. Five patients in the laparoscopy group and seven patients in the Hartmann's procedure group had more than one Clavien-Dindo 1 and 2 complication.

†Not considered a complication as the patient did not have any sign of complication during the re-laparotomy

DISCUSSION

The main findings of the present trial were that laparoscopic lavage for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis (Hinchey III) was feasible and safe. Compared with patients undergoing Hartmann's resection, patients treated with laparoscopic lavage were no different in regard to overall morbidity and short-term mortality. The patients also had shorter duration of surgery and shorter hospital stay after laparoscopic lavage.

There are currently 4 ongoing randomized trials9,12–14 of which this study is the first to publish results after complete accrual. The primary endpoint of this trial is number of reoperations within 12 months, a follow-up time not yet reached for all patients. The present article reports short-term data within 30 days after operation and mortality within 90 days.

Patients undergoing laparoscopic lavage had significantly shorter duration of surgery probably reflecting the less extensive surgical procedure, but it may also somewhat be due to the conversion in the Hartmann's resection group. These patients both had a laparoscopic and an open procedure performed.

After laparoscopic lavage, there was no need for stoma care training, which in part may explain the shorter hospital stay. This will be part of the estimation of health care costs, which will be analyzed after the 12 months’ follow-up.

Diagnostic laparoscopy was feasible in the majority of the patients, and only 4% of the procedures could not be performed due to technical difficulties or severe intra-abdominal inflammation. In patients randomized to laparoscopic lavage the procedure was feasible in all. We found no differences in overall outcomes such as complications or mortality pointing at laparoscopic lavage as a safe alternative to Hartmann's procedure. Mortality after Hartmann's procedure has been reported to be 5.7% to 24%,2,4 which is comparable to our results of 11.4%. Previous reviews have reported considerably lower mortality rates of 1.4% to 1.7% after laparoscopic lavage.7,15 However, these series may be subject to selection bias underestimating mortality rates and it is possible that our mortality rate after laparoscopic lavage of 7.7% probably more closely reflect the true rate in daily clinical practice. Fewer colonic perforations were reported in the laparoscopic lavage group, which probably is due to that the protocol did not require visualization during laparoscopy to define a Hinchey grade III. The handling of the inflamed colon during an open Hartmann's procedure rather than a more advanced disease in the Hartmann's group would be the explanation of the higher rate of visible perforation.

The strengths of this trial were its multicenter randomized design and the fact that the majority of the participating hospitals had screening logs to detect possible selection bias. In our trial, we randomized patients after initial diagnostic laparoscopy to avoid including patients with other diagnoses. The LADIES study also used initial diagnostic laparoscopy before randomization but has stopped accrual for laparoscopic lavage due to safety issues.12,16 The LapLAND as well as the SCANDIV study13,14 randomizes patients before laparoscopy, which may result in the inclusion of patients with other diagnoses. Another important strength in our trial was that all statistical analyses were performed as planned beforehand with no post hoc subgroup analysis. We consider the fact that we had 9 participating hospitals from 2 countries as a strength leading to an increased external validity of the results compared with a single center design. The design of the trial did not require any special training for the surgeons, which also enhances the external validity of our results.

One limitation of this trial was the relatively large number of patients potentially possible to include but not enrolled due to various reasons. However, the reasons for noninclusion of possible candidates were such that no obvious selection bias seems to have been present. Rather the reasons were, as expected in a trial dealing with emergency conditions, difficulties regarding logistics. Another limitation was that there was no general agreement upon classification of complications at the time of the design of the study. Later, the Clavien-Dindo classification11 has been widely used but it was not recognized in early 2009 when this protocol was written. This is compensated in part as reoperations and readmissions were reported in the CRF but we also retrospectively classified all complications according to the Claiven-Dindo classification, but of course there is a risk of misinterpretations, especially regarding grade I and II. It may also be mentioned that the analyses were not adjusted for multiple testing, thus low P values should be regarded as interesting findings rather than conclusive evidence.

Our results may have widespread implications in daily clinical practice when treating patients with complicated diverticulitis. There seems to be an international trend toward not resecting the sigmoid colon even after multiple attacks of diverticulitis, due to a limited risk of perforation after recurrence.17 However, when peritonitis is present, it has until now been the routine to perform Hartmann's procedure. If the long-term results of the present trial together with the results of the other randomized trials support the safety of laparoscopic lavage, then hopefully patients may avoid colon resection and stoma creation and hence some of the well-known short- and long-term complications.3

CONCLUSIONS

Laparoscopic lavage in Hinchey III–perforated diverticulitis was feasible and in the short-term as safe as Hartmann's procedure. We suggest that widespread implementation of the technique should await long-term results from the ongoing randomized trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following contributors: Marina Åkerblom Sörensson, MD, Department of Surgery, Karlstad Hospital; Lars Ilum, MD, Department of Surgery, Holbaek Hospital; Lars Borly, MD, Department of Surgery, Odense University Hospital; Nicolaj Stilling, MD, Thomas Buchbjerg MD, Haldora Patricia Kristófersdóttir, MD, Jan Luxhoi, MD, Department of Surgery, Odense University Hospital/Svendborg.

Footnotes

Disclosure: This study has been funded by the following institutions: The Alderbertska research foundation, ALF—the Agreement concerning research and education of doctors, Alice Swenzons foundation, Anna-Lisa and Bror Björnssons foundation, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the FrF foundation, the Göteborg Medical Society, the Sahlgrenska University Hospital Health Technology Assessment Center, Johan & Jacob Söderberg's foundation, Magnus Bergvall's foundation, Ruth and Richard Julin's foundation, Signe and Olof Wallenius’ foundation, The Swedish Research Council 2012-1770, The Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, and Region Västra Götaland. However, the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hinchey EJ, Schaal PG, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg 1978; 12:85–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris CR, Harvey IM, Stebbings WS, et al. Incidence of perforated diverticulitis and risk factors for death in a UK population. Br J Surg 2008; 95:876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ince M, Stocchi L, Khomvilai S, et al. Morbidity and mortality of the Hartmann procedure for diverticular disease over 18 years in a single institution. Colorectal Dis 2012; 14:e492–e498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornell A, Angenete E, Haglind E. Perforated diverticulitis operated at Sahlgrenska University Hospital 2003-2008. Dan Med Bull 2011; 58:A4173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers E, Hurley M, O'Sullivan GC, et al. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for generalized peritonitis due to perforated diverticulitis. Br J Surg 2008; 95:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toorenvliet BR, Swank H, Schoones JW, et al. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for perforated colonic diverticulitis: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2010; 12:862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alamili M, Gogenur I, Rosenberg J. Acute complicated diverticulitis managed by laparoscopic lavage. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52:1345–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberkofler CE, Rickenbacher A, Raptis DA, et al. A multicenter randomized clinical trial of primary anastomosis or Hartmann's procedure for perforated left colonic diverticulitis with purulent or fecal peritonitis. Ann Surg 2012; 256:819–826.discussion 826–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornell A, Angenete E, Gonzales E, et al. Treatment of acute diverticulitis laparoscopic lavage vs. resection (DILALA): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2011; 12:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg 2012; 10:28–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009; 250:187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swank HA, Vermeulen J, Lange JF, et al. The ladies trial: laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or resection for purulent peritonitis and Hartmann's procedure or resection with primary anastomosis for purulent or faecal peritonitis in perforated diverticulitis (NTR2037). BMC Surg 2010; 10:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter DC. LapLAND laparoscopic lavage for acute non-faeculant diverticulitis. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01019239 Accessed May 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Öresland T. Scandinavian Diverticulitis Trial (SCANDIV). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01047462 Accessed May 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toorenvliet BR, Swank H, Schoones JW, et al. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for perforated colonic diverticulitis: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2010; 12:862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bemelman WA. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or resection for generalised peritonitis for perforated diverticulitis (ladies). Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01317485 Accessed May 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris AM, Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM, et al. Sigmoid diverticulitis: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 311:287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]